Abstract

We evaluated the sensitivity and dose dependency of radiation-induced injury in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Adult C57BL/6 mice were daily exposed to 0, 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray for 1 month in succession, respectively. The damage of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in bone marrow were investigated within 2 hours (acute phase) or at 3 months (chronic phase) after the last exposure. Daily exposure to over 10 mGy γ-ray significantly decreased the number and colony-forming capacity of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells at acute phase, and did not completely recover at chronic phase with 250 mGy exposure. Interestingly, the daily exposure to 10 or 50 mGy γ-ray decreased the formation of mixed types of colonies at chronic phase, but the total number of colonies was comparable to control. Immunostaining analysis showed that the formation of 53BP1 foci in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells was significantly increased with daily exposure to 50 and 250 mGy at acute phase, and 250 mGy at chronic phase. Many genes involved in toxicity responses were up- or down-regulated with the exposures to all doses. Our data have clearly shown the sensitivity and dose dependency of radiation-induced injury in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells of mice with daily exposures to 2 ~ 250 mGy γ-ray.

The exposure to high levels of ionizing radiation is well known to lead to DNA double-strand breaks, which elicit cell death or stochastic change1. As we are always enveloped in a constant exposure to natural ionizing radiation, the detrimental health effects of exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation is still questionable2. By now, the risk evaluation of radiation was general obtained from the epidemiological studies of radiation-exposed human populations because of the lack of ideal in vivo and in vitro approaches for examination. The Life Span Study (LSS) cohort of atomic bomb survivors demonstrated a statistically significant increase in cancer at doses above 100 mGy, but failed to show a significance of cancer risk at lower doses of exposure3. However, a recently cohort study have found that the medical exposure in children to deliver cumulative doses of about 50 mGy might almost triple the risk of leukemia and doses of about 60 mGy might triple the risk of brain cancer4. With the accident of Fukushima Nuclear Power Station in Japan, scientific data is highly and urgently wanted to answer whether a low-dose radiation exposure also induces healthy problem, especially in the future of life span.

Significant advancement of recent studies on stem cells has clearly demonstrated that the small population of tissue-specific stem cells plays critical role in repairing/regenerating the organs due to physiological turnover or non-physiological damage5,6,7. Increasing evidences have also shown that the carcinogenesis, one of the major problems at late phase after radiation is mainly originated from the tissue stem cells, rather than the matured somatic cells8,9. Considering that the changes of stem cells in quality and quantity may serve as potential reliable indicators for sensitively predicting the future health problems in both of cancer and non-cancer risks, many radiobiologists have recently intended to use stem cells as a tool for evaluating radiation-induced injury, especially at the late phase10,11,12.

Generally, low dose is defined as a dose between background radiation (0.01 mSv/day) and high-dose radiation (150 mSv/day)13. In this study, we daily exposed mice to different doses of γ-ray (2 to 250 mGy/day) for 1 month, and then investigated the sensitivity and dose dependency of radiation-induced injury in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells at the acute and chronic phases after a series of radiation exposures.

Results

Daily exposure to 250 mGy γ-ray for 1 month significantly decreased bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs)

All mice survived from the daily radiation exposures to 2 ~ 250 mGy γ-ray for 1 month in succession, as well as within 3 months of follow-up. The body weight was not significantly differed among groups at both of the acute and chronic phases after radiation exposures (Supplementary Figure 1).

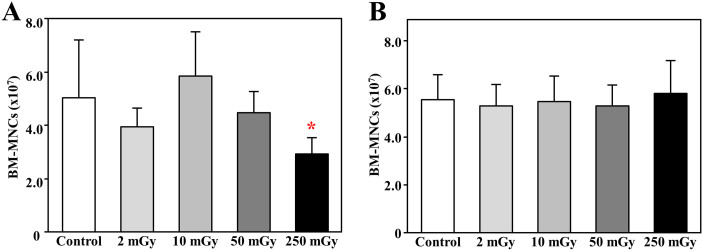

Although the well-trained skill with a defined protocol, significantly less numbers of BM-MNCs were collected from mice soon after the completion of daily exposures to 250 mGy for 1 month (p < 0.05 vs. Control, Fig 1A). No significantly difference in the total number of BM-MNCs was found to be decreased by the exposures to 50 mGy or less (Fig 1A). The decreased number of BM-MNCs with daily 250 mGy radiation exposures was completely recovered within 3 months of follow-up (Fig 1B).

Figure 1. The number of mononuclear cells collected from the bone marrow of mice after radiation exposures.

The bone marrow was collected from the femur and tibia soon (A) or 3 months (B) after daily radiation exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray, and the number of total collected mononuclear cells from each mouse was directly counted. * p<0.05 vs control.

Daily exposure to γ-ray over 10 mGy for 1 month significantly damaged hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells

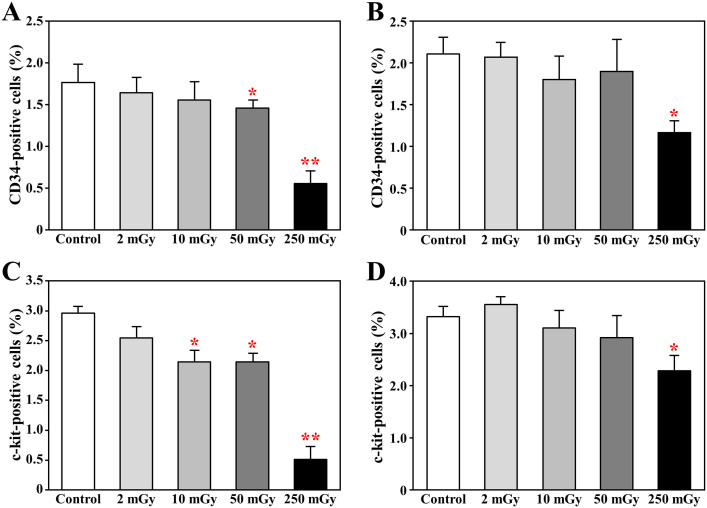

We quantified the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in BM-MNCs by flow cytometry. Compared with the healthy mice, the percentage of CD34+ stem/progenitor cells in the isolated BM-MNCs was significantly decreased in the mice daily exposed to over 50 mGy γ-ray for 1 month (Fig 2A). However, the percentage of c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells in BM-MNCs was significantly decreased in the mice daily exposed to over 10 mGy γ-ray for 1 month (Fig 2C). Both the percentage of CD34+ and c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells at chronic phase was still significantly impaired even 3 months after the completion of daily exposures to 250 mGy for 1 month (Fig 2B, 2D).

Figure 2. The number of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in the bone marrow of mice after radiation exposures.

The mononuclear cells was isolated from bone marrow of mice by gradient centrifugation, soon (A,C) or 3 months (B,D) after daily radiation exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray. The c-kit-positive cells (A,B) or CD34-positive cells (C,D) within bone marrow mononuclear cells were measured by flow cytometry. * p<0.05 vs control; ** p<0.01 vs control.

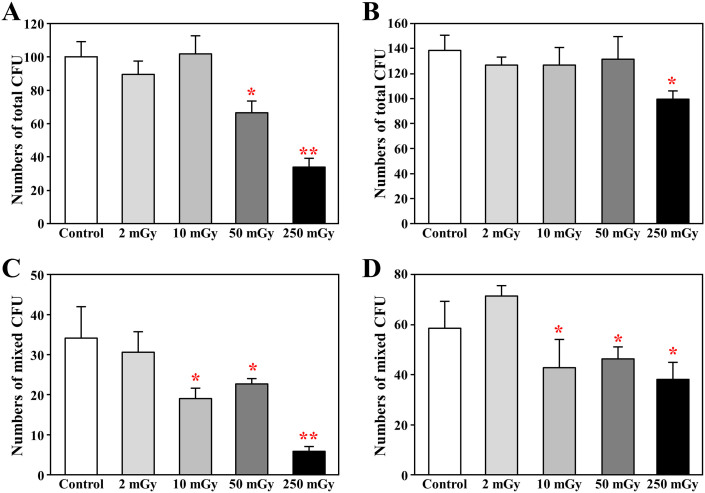

By using colony forming assay, we found that the total number of colonies grew from BM-MNCs was significantly decreased in the mice daily exposed to over 50 mGy γ-ray at acute phase (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 3A), and also significantly decreased in the mice daily exposed to 250 mGy γ-ray at chronic phase (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 3B). To further distinct the sensitivity of different types of stem/progenitor to radiation injury, we also counted the mixed colonies that grown from an early stage stem/progenitor cell with multiple differentiation potency. Interestingly, even if with a daily exposure to 10 mGy for 1 month, the formation of mixed colonies was significantly decreased (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 3C), and this decrease did not completely recovered in 3 months after the completion of daily radiation exposures (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 3D).

Figure 3. Colony-forming assay.

Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated from mice soon (A,C) or 3 months (B,D) after daily radiation exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray, and then cultured in methylcellulose complete medium. The colony formation was observed under microscopy at 9 days after incubation. The number of all types of colonies (>30 cells) and the mixed colonies (at least two types of cells in colony) were counted, and data was represent the mean of duplicate assays. * p<0.05 vs control; ** p<0.01 vs control.

Neither ROS level nor 53BP1 expression sensitively indicated the radiation-induced damage of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells

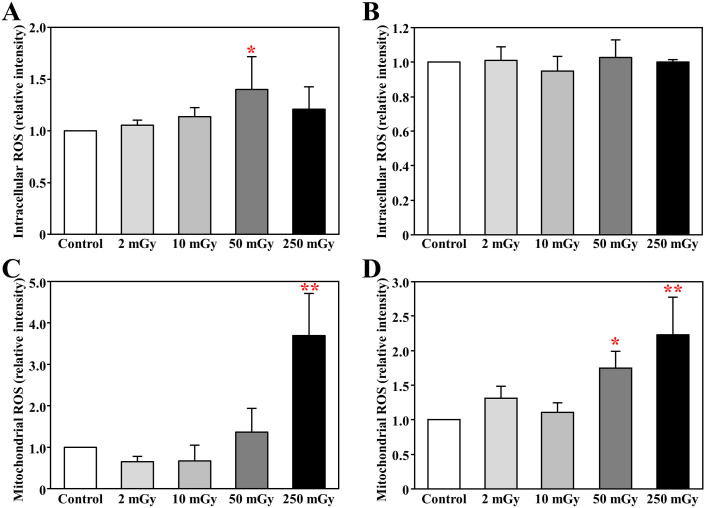

To understand the mechanism on radiation induced damage, we purified c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells for experiments by magnetic cell sorting, and the purity was over 90% by flow cytometry analysis. Unexpectedly, the levels of intracellular ROS in c-kit+ cells was only increased after daily exposure to 50 mGy at the acute phase (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 4A), and was not significantly different among groups at chronic phase (Fig 4B). Given that mitochondria contribute to the increased levels of ROS function to perpetuate the oxidative stress, we also measured the mitochondrial ROS in c-kit+ cells. We found that the mitochondrial ROS levels was increased with daily exposure to 250 mGy γ-ray at the acute phase (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 4C), and also increased even 3 months after the completion of daily exposures to over 50 mGy γ-ray (p < 0.01 vs. Control, Fig 4D).

Figure 4. Intracellular and mitochondrial ROS in the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

The c-kit-positive stem/progenitor cells were purified from freshly collected bone marrow mononuclear cells isolated from mice soon (A,C) or 3 months (B,D) after daily radiation exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray. After 12 hours incubation, cells were then loaded with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA or 5 μM MitoSOX Red at 37°C for 30 minutes. The intracellular ROS (A,B) and mitochondrial ROS (C,D) were detected as the mean fluorescence intensity in all cells by flow cytometry. * p<0.05 vs control; ** p<0.01 vs control.

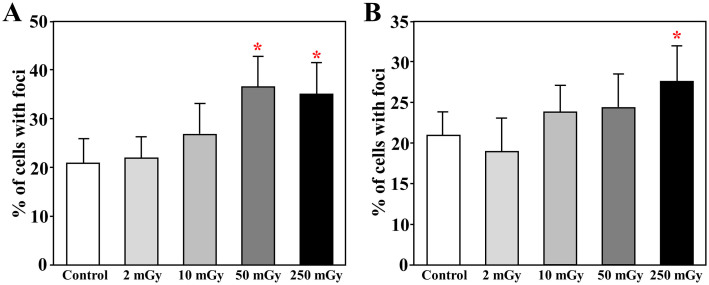

We further evaluated the DNA damage in the purified c-kit+ stem cells based on counting the purified c-kit+ stem cells with the formation of 53BP1 foci in nucleus. A quantitative analysis showed that the percentages of cells with 53BP1 foci were significantly increased in the purified c-kit+ stem cells from mice daily suffered to 50 and 250 mGy for 1 month at the acute phase (p < 0.05 vs. Control, Fig 5A), and also increased in cells from mice daily suffered to 250 mGy at the chronic phase (p < 0.05 vs. Control, Fig 5B).

Figure 5. DNA damage in the c-kit+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

The c-kit-positive stem/progenitor cells were purified from freshly collected bone marrow mononuclear cells isolated from mice soon (A) or 3 months (B) after daily radiation exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray. After 24 hours incubation, cells were fixed and the DNA damage in the cells was estimated by immunostaining with an anti-53BP1 antibody. * p<0.05 vs control.

Radiation-induced changes on the expressions of genes involved in toxicity response in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells

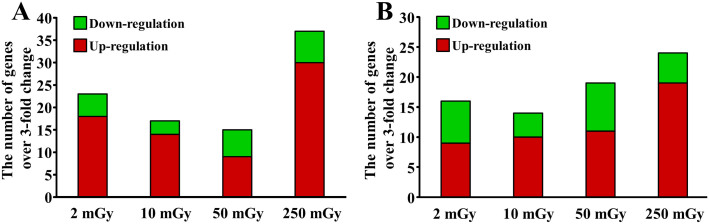

Among the 370 genes included in the Mouse Molecular Toxicology Pathway Finder RT2 Profiler PCR array (Supplementary Table 1), a total of 23, 17, 15, and 37 genes involved in toxicity response were detected to be up- or down-regulated over 3-fold in these c-kit+ stem cells at the acute phase by the daily exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy for 1 month, respectively (Fig 6A). There was still detected 16, 14, 19, and 24 genes that up- or down-regulated over 3-fold in c-kit+ stem cells even 3 months after the completion of daily exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy, respectively (Fig 6B).

Figure 6. Expression of genes involved in toxicity responses in the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

PCR array was performed to compare the expression of 370 genes involved in toxicity responses. The number of genes that up- or down-regulated over 3-fold in freshly purified c-kit-positive stem/progenitor cells from mice soon (A) or 3 months (B) after daily radiation exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray.

The top 20 genes of up- or down-regulation with different doses of exposures were listed up in table (Table). Some genes, such as the Csf2, were found to be up-regulated with all doses of exposures. However, we noticed that each dose of radiation exposure also specifically induced the up- and down-regulation in some genes. These genes specifically changed in each dose of radiation were indicated as red bond fonts in the table (Table). Of that, daily exposure to 2 mGy specifically up-regulated Nr0b2 and HSPb8, 10 mGy specifically up-regulated Lig4 and Prkdc, and 50 mGy specifically down-regulated Trim10 and Tnfsf10 at the acute phase. Otherwise, daily exposure to 250 mGy γ-ray specifically up-regulated Hsph1 and Abl1 at the chronic phase.

Table 1. The top 20 genes that up- or down-regulated in c-kit-positive stem/progenitor cells soon (acute phase) or 3 months (chronic phase) after the completion of daily exposures to 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray for 1 month.

| 2 mGy | 10 mGy | 50 mGy | 250 mGy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Fold change | Gene symbol | Fold change | Gene symbol | Fold change | Gene symbol | Fold change | |

| Acute phase | Slc10a1 | 10.3566 | Slc10a1 | 9.2412 | Slc10a1 | 6.1527 | Csf2 | 20.5222 |

| Csf2 | 6.8328 | Lig4 | 8.1008 | Txnl4b | 4.6629 | Ubqln2 | 19.961 | |

| Nr0b2 | 5.8664 | Sc4mol | 6.225 | Mbtps2 | 4.1446 | Retn | 19.6862 | |

| Acot3 | 5.6666 | Prkdc | 4.5887 | Sc4mol | 3.9757 | Cyp1a2 | 8.1067 | |

| Hspb8 | 5.3982 | Hspa1a | 4.2518 | Csf2 | 3.9483 | Atp6v1g2 | 7.0573 | |

| Mag | 5.3982 | Lss | 4.107 | Ptgs2 | 3.5094 | Cd19 | 6.4492 | |

| Aco1 | 4.5709 | Acot3 | 3.8586 | Serpina3k | 3.4851 | Acot3 | 6.3604 | |

| Serpina3k | 4.3847 | Haao | 3.7792 | Sycp2 | 3.4851 | Lpl | 6.0591 | |

| Ehhadh | 4.3244 | Serpina3k | 3.4776 | Aco1 | 3.2971 | Jph3 | 5.9344 | |

| Atp6v1g2 | 4.0069 | Ephx1 | 3.4297 | Cd19 | 2.8703 | Slc10a1 | 5.8527 | |

| Eno1 | −2.0244 | Ly6d | −2.2688 | Hspa1l | −2.4096 | Fbxo6 | −2.6775 | |

| Ctsb | −2.1251 | Htra2 | −2.3005 | Jag1 | −2.4773 | Mrps18b | −2.6775 | |

| Aldh2 | −2.1547 | Tagln | −2.4485 | Cdkn1a | −2.5647 | Cpt2 | −2.7912 | |

| Dhcr24 | −2.3416 | Gpx4 | −2.4485 | Scd1 | −2.9257 | Fxc1 | −3.2063 | |

| Cd86 | −2.6713 | Gpx3 | −2.5525 | Gpx3 | −3.5278 | Bcl2l11 | −3.3657 | |

| Acox1 | −3.3346 | Trim10 | −2.5703 | Cpt1b | −3.9416 | Tnfsf10 | −3.5086 | |

| Icam1 | −3.4522 | Idh1 | −2.8322 | Icam1 | −4.109 | Bcl2 | −3.533 | |

| Cd36 | −3.5739 | Mrps18b | −3.3448 | Acadsb | −4.5277 | Atf4 | −3.5823 | |

| Ep300 | −4.077 | Acox1 | −3.7371 | Trim10 | −4.6874 | Dld | −4.6942 | |

| Gpx3 | −4.1627 | Tnfsf10 | −4.4442 | Tnfsf10 | −9.9782 | Acat2 | −9.5857 | |

| Chronic phase | Csf2 | 8 | Cyld | 7.4643 | Eif2ak3 | 5.6962 | Cyld | 15.0324 |

| Cyld | 5.5022 | Bax | 6.9644 | Bmf | 5.0281 | Hsph1 | 6.498 | |

| Srebf1 | 5.2054 | Bmf | 4 | Cyld | 4.8568 | Abl1 | 6.0629 | |

| Bax | 4.2871 | Fmo4 | 4 | Bax | 4.0558 | Bmf | 5.7358 | |

| Mrps18b | 3.9177 | Eif2ak3 | 3.8371 | Csf2 | 3.7064 | Bax | 5.3517 | |

| Bcl2l1 | 3.605 | Csf2 | 3.2944 | Acaa2 | 3.5064 | Csf2 | 4.7568 | |

| Ugt2b1 | 3.4822 | Srebf1 | 3.249 | Nudt13 | 3.2944 | Fas | 4.4691 | |

| Hadhb | 3.3636 | Sdhc | 3.249 | Commd4 | 3.2716 | Mag | 4.1989 | |

| Amfr | 3.1821 | Cyp1a2 | 3.1821 | Pcca | 3.0525 | Ahsg | 4.0278 | |

| Acaa1a | 2.8481 | Cyld | 3.0951 | Fmo4 | 3.0314 | Ubqln2 | 4.0278 | |

| Idh1 | −2.7511 | Gpx1 | −2.6574 | Dnajb1 | −2.9282 | Pcna | −2.3295 | |

| Fh1 | −2.9282 | Sod1 | −2.7321 | Ptprc | −2.969 | Ubxn4 | −2.3457 | |

| Tnfrsf1a | −2.9897 | Ero1l | −2.7702 | Atf4 | −3.0951 | Xbp1 | −2.5847 | |

| Os9 | −3.2266 | Brca1 | −2.8879 | Brca1 | −3.1821 | Acat1 | −2.6208 | |

| Sdha | −3.2944 | Acadl | −2.9282 | Cflar | −3.3636 | Fbxo6 | −2.6208 | |

| Serp1 | −3.4343 | Xbp1 | −2.969 | Fxc1 | −3.5308 | Ppp1r15b | −3.1167 | |

| Bcl2 | −3.4581 | Eif5b | −3.0738 | Rad51 | −4.0278 | Sod1 | −3.1383 | |

| Idh3a | −3.8106 | Cflar | −3.4343 | Xbp1 | −4.2281 | Ero1l | −3.1821 | |

| Dlat | −4.1699 | Serp1 | −3.7842 | Casp8 | −4.4076 | Serp1 | −3.249 | |

| Acly | −6.021 | H47 | −6.5432 | H47 | −6.3203 | Gadd45a | −3.6301 | |

Discussion

By daily exposure of health mice to 2 ~ 250 mGy γ-ray for 1 month, we herein demonstrated that radiation exposures declined the number and colony formation capacity of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in bone marrow, in a dose dependent manner. Our data has also suggested that these hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells at earlier stage seem to be more sensitive to radiation, although we did not directly compare with these late stage progenitor cells with limited differentiation potency. Furthermore, the dose-dependent response of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to radiation exposures was also characterized in that different dose of radiation exposure specifically induced the expression change in some genes associated with toxicity response.

DNA damage is known as the direct consequence of high dose ionizing radiation. Moderate or high dose of whole body radiation exposure are well known to cause long-term hematopoietic damage, which has already been experimentally evidenced by the quantitative and/or qualitative defects of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells14,15,16,17. We confirmed that daily exposures to over 50 mGy γ-ray for 1 month significantly induced the formation of 53BP1 foci, one of the markers popularly used for DNA damage identification18, in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells of mice after radiation exposure.

Differed from high dose radiation exposure can directly induce DNA double-strand breaks, the exposure to relatively low dose of radiation is generally thought to induce DNA damage indirectly through the trigger of ROS release, which may finally leading to delayed radiobiological effect19. Recently, it is widely implicated that ROS might play a critical role in intracellular signal induction and gene expression that involves in regulation of hematopoietic stem cell biology and lineage commitment20. The imbalance of ROS homeostasis might induce a series of biological changes and finally resulted in significant damage to the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells21. In the present study, a modest increase of intracellular ROS levels in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells was only found with daily 50 mGy exposures at the acute phase, and no difference at the chronic phase. In contrast, the mitochondrial ROS levels increased with daily 250 mGy exposures at acute phase, as well as with the daily 50 and 250 mGy exposures at chronic phase. However, neither the intracellular ROS levels nor the mitochondrial ROS levels precisely indicated the radiation-induced injures in the number and function of c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells. Therefore, further investigation is needed to confirm the role of ROS in radiation-induced injury in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

Of interesting, daily exposure to 10 mGy γ-ray for 1 month significantly decreased the number of mixed type of colonies that formed from the early stage hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, but not the total number of colonies at both of the acute and chronic phases. Otherwise, daily exposed to 10 mGy γ-ray for 1 month also significantly decreased the percentage of c-kit+ cells, but not CD34+ cells in BM-MNCs at acute phase. As these early stage hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells with multiple differentiation potency are known to be weakly/negatively expressed with CD34, we speculated that these hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells at earlier stage showed higher sensitivity to radiation-induced injury when compared to these late stage hematopoietic progenitor cells that with limited lineage differentiation potency. In fact, it has also previously reported that varying doses of radiation treatment can alter the differentiation of stem cells into their adult progenitor cells22,23. Although some of parameters indicated a recovery of radiation-induced damage in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells within 3 months after the completion of radiation exposures, the formation of mixed colonies still showed significantly impaired with daily exposures to over 10 mGy γ-ray for 1 month. Longer term follow-up may help to answer whether the radiation-induced injury to these hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells at early stage will be permanent or recoverable.

By extensive screening the changes of gene expression, we found that a number of genes involved in toxicity responses were up- or down-regulated over 3-fold in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells at acute phase, even by the daily exposure to a dosage of 2 mGy (Supplementary Table 1). Some gene, such as Csf2, was generally enhanced in response to all doses of radiation exposures in study, and the number of genes with over 3-fold change was not proportionally increased with the doses of radiation exposure. The most interesting finding to us was the dose specificity on the gene expression changes. Our data showed that the daily exposure to 2 mGy, but not other doses, largely up-regulated HspB8 and Nr0b2. The HspB8, a small heat shock protein, has been demonstrated to implicate in autophagy and participate in protein quality control by a non-chaperone-like mechanism24. The Nr0b2, an orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner, has been reported to be a potential tumor suppressor in human liver cancer25. Therefore, we speculate that the specifically up-regulation of HspB8 and Nr0b2 in response to 2 mGy of low dose radiation may beneficial of the protein quality control in the stem cells and inhibit carcinogenesis. However, it is still kept to discreetly claim the concept that a subtle dose radiation exposure will benefit the cells instead of inducing defect to the cells26,27.

Daily exposure to10 mGy showed to specifically up-regulate Prkdc and Lig4, two genes that well known to relevant with DNA-damage repair28. Although the expression of 53BP1 in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells was not changed with 10 mGy exposures by immunostaining analysis, the up-regulation of Prkdc and Lig4 may due to some radiation-induced repairable DNA damages in these c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells with daily 10 mGy exposures.

Down-regulation of Trim10 and Tnfsf10 was specially observed in the c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells with daily exposure to 50 mGy. The Trim10 has been demonstrated to be a key factor required for terminal erythroid cell differentiation and survival29. The Tnfsf10 is known as a p53-transcriptional target gene30. The largely down-regulation of Trim10 and Tnfsf10 in the c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells with daily exposure to 50 mGy probably indicates a severe damage of hematopoiesis and the increased risk of carcinogenesis.

Similar to the acute phase, many genes was still detected to be up- and down-regulated over 3-fold in these in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells at the chronic phase. The expression of some genes, including the Abl1 and Hsph1 was specifically up-regulated even 3 months after the completion of daily exposure with a very high dose of 250 mGy. The mutation in the Abl1 gene has previously been demonstrated to associate with chronic myelogenous leukemia31. On the other hand, Hsph1 has been displayed a direct correlation between HSP105 expression and lymphoma aggressiveness32. As the carcinogenesis are considering to be originated from the stem cells rather than matured tissue cells, the increased expressions of Abl1 and Hsph1 in these c-kit+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells may finally contribute to increase the risk of carcinogenesis and to enhance the aggressiveness of cancer.

Although the extensive changes of gene expression were detected, further experiment is highly required for uncovering the mechanism and significance of these changes of gene expression with both cell biological and radiobiological views. Otherwise, we did only purify the c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells using for study, it is still kept unclear about the sensitivity and dose-dependency of radiation-induced injury to these lin− sca-1+ c-kit+ (LSK) long-term hematopoietic stem cells.

In summary, data from the present study has clearly indicated the sensitivity and dose dependency of radiation-induced injury of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in bone marrow of mice after daily exposures to γ-ray with a wide dose range from 2 to 250 mGy, further experiment is badly in need in ascertaining the exact effect of low dose radiation exposure, especially the lowest dose level of radiation exposure for evidence of elevated cancer and non-cancer risks.

Methods

Animals

We used 12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (SLC, Japan) for the present study. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nagasaki University (No. 1108120943), and experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional and national guidelines.

Radiation exposures

Whole-body radiation was performed by exposing the mice to 0, 2, 10, 50, and 250 mGy γ-ray daily for 30 days in succession (with accumulative doses of 0, 60, 300, 1500, and 7500 mGy), respectively33. The mice were sacrificed within 2 hours (acute phase) or 3 months later (chronic phase) after the last exposure, and bone marrow cells were collected and used for the following experiments.

Measurement of the number of mononuclear cells and stem cells in bone marrow

Bone marrow cells were collected from the femur and tibia. The bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation33,34, and then counted using a Nucleo Counter cell-counting device (Chemotetec A/S, Denmark). To measure the c-kit-positive (c-kit+) and CD34-positive (CD34+) stem/progenitor cells in the isolated BM-MNCs, we labeled cells with a PE-conjugated anti-mouse c-kit antibody (eBioscience) or a FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD34 antibody (BD Bioscience) for 30 minutes. Respective isotype controls were used as a negative control. After washing, quantitative flow cytometry analysis was performed using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson)33,34. We analyzed the acquired data using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

Colony-forming assay

The colony-forming capacity of the isolated cells was evaluated using mouse methylcellulose complete medium33,34, according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D System). Briefly, 3 × 104 BM-MNCs were mixed well with 1 ml of medium, plated in 3-cm culture dishes, and then incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The formation of colonies was observed under a microscope, and the total number of colonies in each dish was counted after 9 days of incubation. We also counted the number of mixed colonies, in which at least two types of cells was grown from a single stem/progenitor cell. The mean number of colonies in duplicate assays was used for the statistical analysis.

Purification of c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells

The c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells were purified by sorting, using the Magnetic Cell Sorting system (autoMACS, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA)35. Briefly, freshly collected BM-MNCs were incubated with anti-mouse CD117 (c-kit) antibody (Miltenyi Biotec) for 30 minutes. After washing, c-kit+ cells were separated by passing a MACS column. The purity of the c-kit+ cells collected by the autoMACS was about 90%, and the viability was more than 99%.

Detection of intracellular and mitochondrial ROS levels in c-kit+ stem/progenitor cells

To measure the intracellular and mitochondrial ROS levels, freshly purified c-kit+ cells were seeded on 96-well culture plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 100 μl IMDM 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 12 hours. Cells were then incubated with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA or 5 μM MitoSOX Red (Molecular Probes Inc.)36,37, at 37°C for 30 minutes. After washing, the fluorescence intensity in the c-kit+ cells was measured by plate reader (VICTOR™ ×3 Multilabel Plate Reader, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

To detect the DNA damage, freshly purified c-kit+ cells were seeded on 4-well chamber culture slides (Nalge Nunc International, Roskilde, Denmark) coated with 10 μg/ml fibronectin (Invitrogen) at a density of 3 × 104 cells/ml in IMDM 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 hours, and then fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. After blocking with 2% bovine serum albumin, the cells were reacted with anti-mouse 53BP1 antibody (Abcam), followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258. The positively stained cells were observed under fluorescence microscopy with 200-fold magnification, and more than 200 cells were counted to calculate the percentage of cells with 53BP1 foci in the nucleus33,34.

Mouse Molecular Toxicology Pathway Finder RT2 Profiler PCR array

Total RNA was isolated from the freshly purified c-kit+ cells by using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). We took 1 mg of RNA from each sample and mixed to generate cDNA using RT2 First Strand Kit (SABiosciences). Mouse Molecular Toxicology Pathway Finder RT2 Profiler PCR array was done according to the manufacturer's instructions (SABiosciences), and a total of 370 genes representative of the 13 biological pathways involved in response to toxicity was included in array (Supplementary Table 1). The fold change of expression was calculated using web-based data analysis program (SABiosciences).

Statistical analyses

All results are presented as the means ± SD. The statistical significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc test (Dr. SPSS II, Chicago, IL). Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

T.L. conceived and designed the experiments. C.G., L.L., Y.U., S.G., W.H., S.T., F.H., H.D., Y.K., Y.O., T.O. and T.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. C.G., L.L. and T.L. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology, Japan, and by Uehara Memorial Foundation and Mochida Memorial Foundation. No additional external funding received for this study. The founders did not participate in this study.

References

- Huang L., Snyder A. R. & Morgan W. F. Radiation-induced genomic instability and its implications for radiation carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 22, 5848–5854 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. et al. Targeted and nontargeted effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on delayed genomic instability in human cells. Cancer Res. 67, 1099–1104 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston D. L. et al. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors: 1958–1998. Radiat Res. 168, 1–64 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce M. S. et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 380, 499–505 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Zhao R. C. & Tredget E. E. Concise review: bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells in cutaneous repair and regeneration. Stem Cells. 28, 905–915 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright K. T. et al. Concise review: Bone marrow for the treatment of spinal cord injury: mechanisms and clinical applications. Stem Cells. 29, 169–178 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benderitter M. et al. Stem cell therapies for the treatment of radiation-induced normal tissue side effects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 21, 338–355 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader J. E. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature. 469, 314–22 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T. et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 414, 105–111 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prise K. M. & Saran A. Concise review: stem cell effects in radiation risk. Stem Cells. 29, 1315–1321 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj K. & Bouffler S. DoReMi stem cells and DNA damage workshop. Introduction. Int J Radiat Biol. 88, 671–676 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voswinkel J. et al. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in chronic inflammatory fistulizing and fibrotic diseases: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 45, 180–192 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner W. M. Low-dose radiation: thresholds, bystander effects, and adaptive responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100, 4973–4975 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch P. et al. Hematopoietic stem cell compartment: acute and late effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 31, 1319–1339 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Total body irradiation selectively induces murine hematopoietic stem cell senescence. Blood. 107, 358–366 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Total body irradiation causes residual bone marrow injury by induction of persistent oxidative stress in murine hematopoietic stem cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 48, 348–356 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L. et al. Total body irradiation causes long-term mouse BM injury via induction of HSC premature senescence in an Ink4a- and Arf-independent manner. Blood. 123, 3105–3115 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz L. B. et al. p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) is an early participant in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Cell Biol. 151, 1381–1390 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga H. et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the induction of genetic instability by radiation. J Radiat Res. 45, 181–188 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah E. & Banerjee U. Reactive oxygen species prime Drosophila haematopoietic progenitors for differentiation. Nature. 461, 537–541 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M. & Kashiwakura I. Role of reactive oxygen species in the radiation response of human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. PLoS One. 8, e70503; 10.1371/journal.pone.0070503(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter R. L. et al. Prostaglandin E2 increases hematopoietic stem cell survival and accelerates hematopoietic recovery after radiation injury. Stem Cells. 31, 372–383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzen S. et al. Characteristics of myeloid differentiation and maturation pathway derived from human hematopoietic stem cells exposed to different linear energy transfer radiation types. PLoS One. 8, e59385; 10.1371/journal.pone.0059385(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carra S. et al. HspB8 participates in protein quality control by a non-chaperone-like mechanism that requires eIF2{alpha} phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 284, 5523–5532 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. Y., Choi H. S. & Lee J. S. Systems-level analysis of gene expression data revealed NR0B2/SHP as potential tumor suppressor in human liver cancer. Mol Cells. 30, 485–491 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinendegen L. E. Evidence for beneficial low level radiation effects and radiation hormesis. Br J Radiol. 78, 3–7 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss M. Evidence supporting radiation hormesis in atomic bomb survivor cancer mortality data. Dose Response. 10, 584–592 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll M. & Jeggo P. A. The role of double-strand break repair - insights from human genetics. Nat Rev Genet. 7, 45–54 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaybel R. et al. Downregulation of the Spi-1/PU.1 oncogene induces the expression of TRIM10/HERF1, a key factor required for terminal erythroid cell differentiation and survival. Cell Res. 18, 834–845 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribayashi K. et al. TNFSF10 (TRAIL), a p53 target gene that mediates p53-dependent cell death. Cancer Biol Ther. 7, 2034–2038 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R. Mechanisms of BCR-ABL in the pathogenesis of chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 5, 172–183 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappasodi R. et al. Serological identification of HSP105 as a novel non-Hodgkin lymphoma therapeutic target. Blood. 118, 4421–4430 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakatsu M. et al. Nicaraven attenuates radiation induced injury in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in mice. PLoS One 8, e60023; 10.1371/journal.pone.0060023 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakatsu M. et al. Placental extract protects bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells against radiation injury through anti-inflammatory activity. J Radiat Res. 54, 268–276 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. S. et al. Diabetic impairment of c-kit+ bone marrow stem cells involves the disorders of inflammatory factors, cell adhesion and extracellular matrix molecules. PLoS One. 6, e25543; 10.1371/journal.pone.0025543 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. S. & Marbán E. Physiological levels of reactive oxygen species are required to maintain genomic stability in stem cells. Stem Cells. 28, 1178–1185 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction, a probable cause of persistent oxidative stress after exposure to ionizing radiation. Free Radic Res. 46, 147–153 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data