Abstract

Osteochondroma is a rare tumor of the mandibular condyle. Much confusion seems to exist in the literature in differentiating these tumors from chondromas as well as condylar hyperplasias.

Due to considerable overlapping features between chondromas and condylar hyperplasia, it is likely to get misdiagnosed, thereby resulting in inadvertent errors in the treatment.

A case report of a 35 year old male patient with mandibular deviation and malocclusion is presented here. He initially went unnoticed for features of an osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle but was subsequently treated for the same.

Keywords: Osteochondroma, Mandibular deviation, Facial asymmetry, Condylar hyperplasia

1. Introduction

Osteochondroma or solitary osteo-cartilaginous exostosis is an exophytic lesion that arises from the cortex of bone and is capped with cartilage.1 It is one of the most common benign tumors of the bone, representing 35%–50% of all benign bone tumors and 8%–15% of all primary bone tumors.2 Although frequently found in the general skeleton, it is most infrequently seen to involve the facial bones. The coronoid process and the mandibular condyle are the affected areas especially the medial aspect of the mandibular condyle. At present in English literature, there are a total of 98 cases of mandibular condylar osteochondroma3 reported between 1927 and 2010. It reveals a female preponderance, with male: female ratio of 1:1.6 and age range of 13 years–70 years (mean 38.4 years).3 However, there are no large studies available for review because most of the literature consists of only single case reports.

In this report, an interesting case of an osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle in a 35 year old male patient who was initially considered to have deviated mandibular prognathism is presented. The panoramic radiograph showed a normal shaped left condylar head due to which the presence of osteochondroma was initially missed. The overlapping radiographic, clinical and histologic similarities between condylar hyperplasia and osteochondromas are discussed in detail. The need to recognize the importance of an initial correct diagnosis for an osteochondroma and the differences in the management between the entities is emphasized.

Since the osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle arises from different sites around the condyle and presents diverse shapes on panoramic radiographs, only plain radiographs features may not help us in the exact diagnosis. If the CT and MRI techniques are integrated, the diagnosis becomes more reliable.

2. Case report

A 35 year old male patient reported to the Maxillofacial OPD at Nair Hospital Dental College with the complaint of progressive facial asymmetry, difficulty in speech and mastication for the past 1 year. More recently, the patient had also experienced mild difficulty in opening the mouth. There was no history of trauma, infection in and around the TMJ or ear and no similar complaints in the past.

History revealed that 2 years back, the patient had presented with lesser similar signs of facial asymmetry and deviated mandible to the right side at the same institution for which he had undergone bilateral sagittal split osteotomy and differential mandibular setback to correct the prognathism and midline shift. The correction of his facial asymmetry was undertaken after scintigraphy tests which clearly showed no hotspots for left TMJ region and after ruling out any endocrinologic abnormalities. The patient's general condition was otherwise normal.

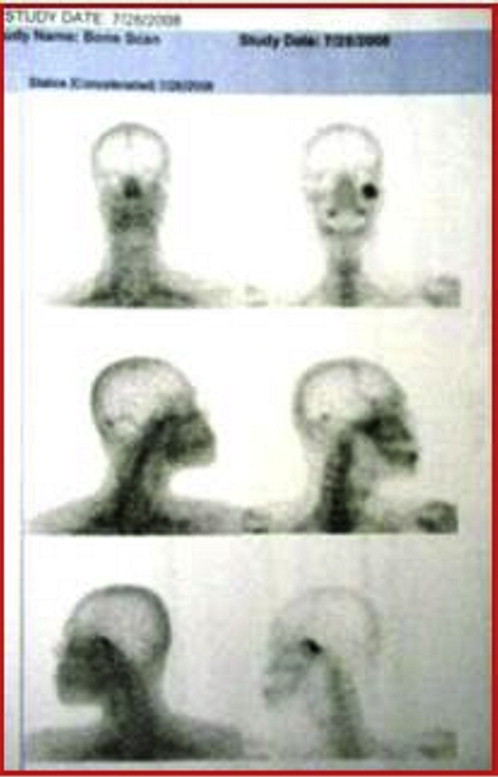

Clinical examination showed extensive facial asymmetry with mandibular deviation to the right which was a major concern for the patient (Fig. 1). The mandibular midline was deviated by 7 mm to the right of the maxillary dental midline, reflecting an asymmetric prognathism. Inter-incisal mouth opening at examination was 35 mm. There was an ipsilateral open-bite and a contra-lateral cross-bite. No obvious canting of occlusion was evident. Lateral jaw movements were restricted.

Fig. 1.

Pre- operative – frontal view.

The panoramic radiograph again did not reveal any abnormality with the left condylar head (Fig. 2). However, the axial and coronal CT scans revealed an opaque mass that was located on the medial aspect of the left mandibular condyle extending medially and superiorly (Fig. 3) 3D CT and other images interestingly revealed a normal condylar shape anterolaterally with no distinct enlargement (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Pre- operative OPG 2 years later (no condylar abnormality).

Fig. 3.

Coronal CT scan showing continuity of the cortex and medulla of the tumor with the condyle of the mandible, a feature diagnostic of osteochondroma.

Fig. 4.

3D CT scans.

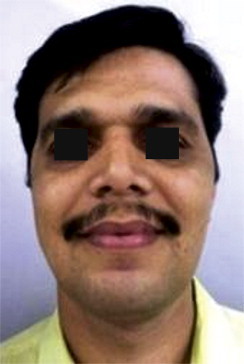

Scintigraphy with Tc99m showed a hotspot in the left condylar region (Fig. 5) The Endocrinology studies were within normal limits. Conclusively it was diagnosed to be a case of an osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle.

Fig. 5.

Bone scans (scintigraphy).

The patient was taken up for surgery under general anesthesia. Al Kayat & Bramley's incision was taken on the left side and a flap was reflected. Blunt dissection was carried out along the layer of loose areolar tissue to expose the zygomatic arch. A‘T-shaped’ incision was taken over the fibrous capsule of the condyle. The morphology of the left condylar head clearly appeared normal on the lateral aspect. The tumor mass was attached on the medial aspect of the left condylar head extending medially and superiorly and was locked under the zygomatic arch.

The articular eminence was reduced vertically; the middle third of the zygomatic arch was osteotomized, moreover a condylotomy was also done to gain access and facilitate removal of the tumor mass. The tumor was dissected from its soft tissue attachments, an osteotomy cut was given at the base of the tumor mass attached to the medial aspect of the condylar head and was removed in toto. The articular disc which appeared normal but displaced was replaced and sutured in position. Refixation of the osteotomized zygomatic arch was done with 6-hole stainless steel mini-plate and screws. The condylar position and the occlusion were retained with positional maxillomandibular fixation for 3 weeks. The post- operative course was uneventful. (Fig. 6) Active jaw exercises, including vertical jaw opening, lateral excursions, and protrusion were performed 4–6 times per day following release of intermaxillary ligation for next 3 weeks.

Fig. 6.

Post- operative frontal view.

The excised mass was irregular in shape measuring 25 × 30 × 35 mm, had a nodular surface covered with a tissue that was found to be hard in consistency. On the basis of the histopathologic features a diagnosis of osteochondroma was confirmed.

3. Discussion

Osteochondroma is a relatively common finding in the skeleton, occurring frequently in the metaphyseal region of the long bones. It is also found in the ribs, scapulae, clavicles, and vertebrae.4 In the maxillofacial region, the occurrence of osteochondromas is infrequently reported. The majority of extracondylar osteochondromas in this region occur on the coronoid process. However, cases have been reported in the posterior maxilla, maxillary sinus, zygomatic arch, mandibular body and symphysis.5 Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle is extremely unusual.2 Those involving the mandibular condylar region, are found most often on the medial aspect of the mandibular condyle (52%), followed by an anterior location (20%), but rarely on the lateral or superior positions (1%).3

Origin of osteochondroma is controversial. Different theories of etiopathogenesis – neoplastic, developmental, reparative, and traumatic have been proposed and discussed.6,7 Radiation-induced osteochondroma is also reported in the literature.8 However, presently none of these theories are sufficient to explain all the cases of osteochondromas. Among the reported benign tumors of the condyle, chondroma, osteomas and osteochondromas; osteochondromas are most common.9 Condylar osteochondromas are usually situated on the anteromedial surface of the condylar head.5,10 The occurrence of these tumors in the condyle tends to support the theory of aberrant foci of epiphyseal cartilage on the surface of the bone.11 It is accepted that stress in the tendonous insertion region of lateral pterygoid muscle, where focal accumulations of cells with cartilaginous potential exists, leads to formation of these tumors. This may also explain the occurrence of osteochondromas in the coronoid process, which is stressed by the tension of temporalis muscle.4 The occurrence of osteochondromas most often on the medial aspect of condyle (52%) further supports the reason for their growth potential due to consistent stimulation by lateral pterygoid muscle tendons during lateral excursions. In the present case, the mass appeared spontaneously and gradually increased in size since 1 year from medial aspect of the left condyle where the lateral pterygoid is attached.

Osteochondromas are often slow growing. The presentation of condylar osteochondroma includes development of facial asymmetry, malocclusion, cross-bite on contra-lateral side and lateral open-bite on the affected side, deviation on opening, hypomobility, pain and clicking.4,12 When considering the diagnosis of mandibular condylar osteochondroma, one must entertain other possibilities in the differential diagnosis. A clinical differential diagnosis of slow-growing masses of the mandibular condyle should include giant cell tumor, condylar hyperplasia, fibro-osseous lesion, vascular malformation, osteoma, chondroma, and osteochondroma. More rarely reported condylar tumors have included chondroblastoma, chondrosarcoma, osteoid osteoma, endochondroma, osteosarcoma, and metastatic tumors.5

Considerable confusion exists between osteochondromas and unilateral condylar hyperplasia. However as the treatment plan differs for both these conditions, it is mandatory that clinico-pathological and radiological differentiation should be carried out between the two entities. Unilateral condylar hyperplasia is manifested clinically and radiographically as an enlarged condylar process13 whereas the osteochondroma is seen in 52% cases as a globular projection extending from the medial margins of the condylar head. Interestingly, a normal outline of the condylar head is maintained. The growth of the osteochondroma continues and progresses much longer even after the termination of skeletal growth while in the case of condylar hyperplasia, growth ceases.

Plain radiographs do not portray such a picture. Pre-operative CT plays a pivotal role in the treatment planning of these tumors. CT clearly depicts the continuation of the cortex and medulla of the parent bone with that of the tumor, a feature most diagnostic of the osteochondromas. 3D CTs may also reveal a normal condylar head, but it is the coronal CT which plays a most decisive and invaluable role, in the diagnosis. The coronal CT view reveals a growth arising medially from the morphologically normal condyle; the other views may not be useful in portraying this picture. Condylar hyperplasia will be seen only as a uniform enlargement of the condylar head. Histopathologically, condylar hyperplasia reveals a pattern of cartilage proliferation whereas osteochondroma has aberrant cartilage proliferation and calcification, in addition to the cartilage cap, a characteristic feature.13

A bone scan is not specific as a similar uptake can also be found in joints undergoing remodeling and inflammation, e.g. osteoarthritis.

Depending on the symptoms and duration of the osteochondroma, the management ranges from excision of the tumor alone to condylectomy along with tumor excision. This may be the only treatment required in the initial stage without marked dentofacial deformities. A pre-auricular surgical approach has been used most of the times, however, submandibular and intraoral approaches have also been used.5

In our case a condylotomy was done just to gain access to facilitate removal of the tumor mass attached to the medial aspect of the condylar head and the functional occlusion was achieved. Since there was no obvious facial deformity, no further correction was required. The patient was given MMF for three weeks followed by functional elastic guidance for three weeks to guide the mandible back into occlusion. Post-operative exercises were begun as soon as possible. Early mobilization is one of the most important factors to prevent the potential of occurrence of fibrous adhesions. The indication for early removal of the condylar growth in this region emphasizes the need for an early diagnosis and resection in regard to malignant transformation and the risk of recurrence which has been described in the literature.7,9,14

Generally the indication for condylectomy seems to be based on the technical difficulties encountered while achieving an adequate broad exposure to enable a selective yet radical tumor resection. Most condylar osteochondromas are located on the anteromedial surface of the condylar process and are adjacent to and extend up to the carotid and jugular vessels and a broad exposure is obligatory. For this purpose, the need to osteotomize the zygomatic arch has been recommended.15 Because the shape and size of the condylar head remained unaffected the need for total condylectomy was not required. Only to gain access a part of condylar head was reduced.

In our case, initially when the patient reported with facial asymmetry the plain radiographs did not provide any information regarding the osteochondroma since the bone scan failed to show any activity, the patient was treated for his deviated mandibular prognathism with differential bilateral sagittal split setback osteotomy. However, the patient reported two years later with extensive facial asymmetry, severe mandibular deviation to the right and cross-bite with occlusal derangement and difficulty in mouth opening. A CT study was then advised. The coronal CT plates revealed an enlarged mass arising from the medial aspect of the left condyle. A repeat bone scan revealed a hot spot in the left condylar region. The patient was hence treated with tumor excision in toto.

There is a possibility that the initial presentation of the patient could have been due to osteochondroma which was missed. The lack of CT scans during the initial presentation of the case further prevented a correct diagnosis. Coronal and axial CTs taken two years later clinically showed the presence of an osteochondroma on the medial aspect of the left condyle which was the cause of the patient's worsened deviated mandibular prognathism. The coronal CT studies thus played a vital role in the diagnosis of osteochondroma. It is mandatory to reach to a final diagnosis with the help of CTs so as to execute the correct treatment plan, failing which, the tumor would continue growing and the deformity could worsen.

This case clearly highlights the importance of computed tomography especially in the coronal plane which may be considered mandatory in cases of patients reporting with increasing deviated mandibular prognathism.

Bone scans too play a crucial role in reflecting the activity of condylar growth.16 However, an inactive report can be obtained when the disease is in quiescent phase; thus explaining our patient's inactive bone scan report in the first instance.

Thus, it can be emphasized that CTs play a crucial role in the correct execution of the treatment plan for patients with signs of increased condylar activity, and in the diagnosis of a possible osteochondroma of the condylar region especially, the medial aspect.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Ribas, Martins, Zanferrari, Lanzoni Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: literature review and report of a case. J Contemp Dent Pract. May 1, 2007;6(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J., Wang H., Li X. Osteochondromas of the mandibular condyle: variance in radiographic appearance on panoramic radiographs. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:154–160. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/19168643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy Choudhury Ajoy, Bhatt Krushna, Yadav Rahul, Bhutia Ongkila, Roy Choudhury Sunanda. Review of osteochondroma of mandibular condyle and report of a case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2815–2823. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolford L.M., Mehra P., Franco P. Use of conservative condylectomy for treatment of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:262–268. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.30570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vezeau P.J., Fridrich K.L., Vincent S.D. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: literature review and report of two atypical cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:640. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seki H., Fukuda M., Takahashi T., Iino M. Condylar osteochondroma with complete hear losss: report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:131–133. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peroz I., Scholman H.J., Hell B. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:455–456. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper G.D., Dicks Mireaux C., Leiper A.D. Total body irradiation induced osteochondroma. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aydin M.A., Kucukcelebi A., Sayilkin S., Celebioglu S. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: report of 2 cases treated with conservative surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1082–1089. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.25049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munoz M., Goizueta C., Gil-Diez J.L. Osteocartilaginous exostosis of mandibular condyle misdiagnosed as temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:494. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karas S.C., Wolford L.M., Cottrell D.A. Concurrent osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle and ipsilateral cranial base resulting in temporomandibular joint ankylosis: report of case and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:640–646. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsell H., Happonen R.P., Forsell K., Virolainen E. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: report of a case and review of the literature. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:183. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avinash K.R., Rajagopal K.V., Ramakrishnaiah R.H., Carnelio S., Mahmood N.S. Computed tomographic features of the mandibular osteochondroma – case report. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2007;36:434–436. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/54329867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ord R.A., Warburton G., Caccamese J.F. Osteochondroma of the condyle: review of 8 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar V.V. Large osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle treated by condylectomy using a transzygomatic approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;39:188–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmlund A.B., Gynther G.W., Reinhott F.P. Surgical treatment of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle in adult. A 5-year follow up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]