Abstract

Why do neurons sense extracellular acid? In large part, this question has driven increasing investigation on acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) in the CNS and the peripheral nervous system for the past two decades. Significant progress has been made in understanding the structure and function of ASICs at the molecular level. Studies aimed at clarifying their physiological importance have suggested roles for ASICs in pain, neurological and psychiatric disease. This Review highlights recent findings linking these channels to physiology and disease. In addition, it discusses some of the implications for therapy and points out questions that remain unanswered.

Acid-evoked currents were first observed in neurons in the early 1980s1,2. In 1997, a protein producing a similar acid-gated current was cloned and identified as an acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC)3. This protein was closely related to a previously cloned member of the degenerin–epithelial Na+ channel family (DEG–ENaC family; also called BNC1, MDEG or BNaC1 by three separate groups)4–6. This and other related channel family members were subsequently found to be pH-sensitive7 and renamed ASICs to reflect their related structure, function and pH sensitivity8. We now know that the ASIC family of channel subunits (TABLE 1) is largely responsible for the acid-evoked currents previously observed in neurons1,2.

Table 1.

ASIC subunits and properties

| ASIC subtype | pH sensitivity of homomeric channel (pH50) | Localization |

|---|---|---|

| ASIC1A | 5.8–6.8 | CNS and PNS |

| ASIC1B | 6.1–6.2 | PNS, not yet identified in the CNS |

| ASIC2A | 4.5–4.9 | CNS and PNS |

| ASIC2B | Does not form pH-sensitive homomeric channels, associates with other ASICs to form pH-sensitive channels | CNS and PNS |

| ASIC3 | 6.4–6.6 | Predominately PNS, detected in mesencephalic trigeminal neurons in the CNS114 |

| ASIC4 | Does not form pH-sensitive homomeric channels | CNS |

Four acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) genes (ASIC1, ASIC2, ASIC3 and ASIC4) and six ASIC subunits (ASIC1A, ASIC1B, ASIC2A, ASIC2B, ASIC3 and ASIC4) have been identified. pH sensitivity varies widely across ASIC subtypes. Various pH50 values have been seen across studies, reflecting differences in cell type, species and technique. A representative range of pH50 values from two studies27,28 that used consistent methods to evaluate all channel subtypes is given in the table. Heteromeric channels comprised of combinations of the above subtypes have unique channel properties17. Various ASIC subtypes have been detected in both the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS).

A number of excellent reviews have focused on ASIC structure, function and physiology9–17. Many studies on ASICs have focused on their potential physiological roles. Much of this work has been guided by channel subunit localization in peripheral and central neurons (TABLE 1). In peripheral sensory neurons, ASICs have been found on cell bodies and sensory terminals, where they have been suggested to be important for nociception and mechanosensation18,19. In central neurons, ASICs have been found on the cell body, dendrites and at dendritic spines and have been suggested to contribute to synaptic plasticity20–22. The aim of this Review is to update readers on recent progress on ASICs in the context of disease. Increasing evidence supports roles for ASICs in rodent models of pain, neurological disease and psychiatric disease.

ASICs: a brief background

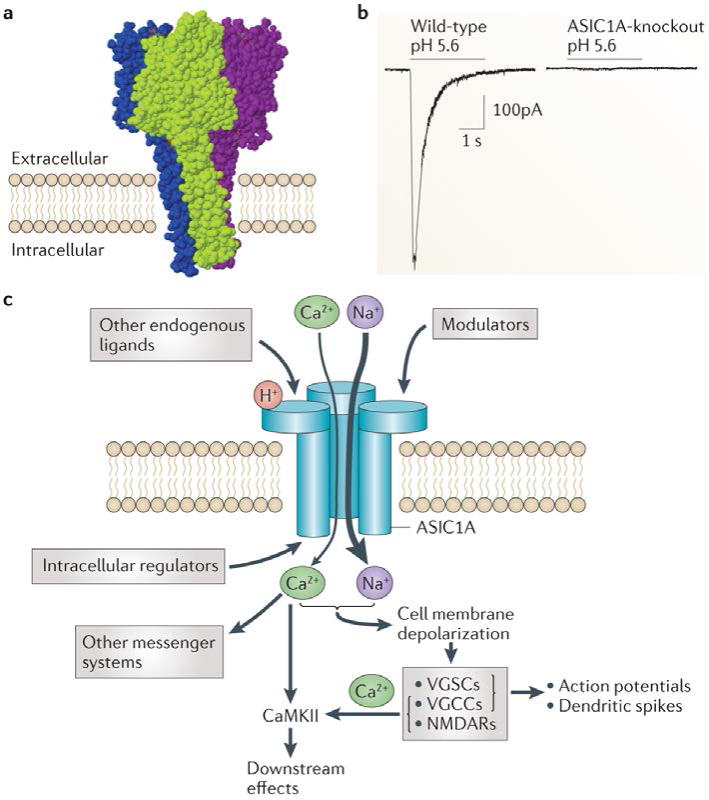

ASICs are permeable to cations and are activated by extracellular acidosis. They are subject to modulation by extracellular alkalosis23,24, intracellular pH25,26 and various other factors (TABLE 2). Much of what we know about these channels’ properties comes from expressing recombinant ASIC subunits in heterologous cells7,13,27–29. Channels are formed by combinations of ASIC subunits in homotrimeric or heterotrimeric complexes (FIG. 1a), with different subunits conferring distinct properties (TABLE 1). The amino acid sequences of ASIC subunits are well conserved between species. For example, the mouse ASIC1A and the human ASIC1A share over 99% of their amino acid sequence identity. The recently described crystal structure of the chicken ASIC1 homomultimeric channel has shed light on the subunit interactions30,31 (FIG. 1a) and, along with sequence homology analyses, has driven numerous structure–function experiments that are revealing how the channels respond to pH and other stimuli. Interestingly, in addition to the non-covalent inter-subunit interactions, disulphide bonds between trimers may also create higher-order complexes and alter channel function32.

Table 2.

Pharmacology of ASICs

| Class | Compound | Effects on ASICs | Site of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous modulators | |||

| Neuropeptides | Dynorpin A, big dynorphin | Increase acid-evoked current by limiting steady-state desensitization of ASIC1A115, ASIC1A–ASIC2B and ASIC1A–ASIC2A heteromers78 | Extracellular; big dynorphin competes with PcTx1 (REFS 115, 116) |

| Phe-Met-Arg-Phe (FMRF) amide and related peptides | Enhance sustained acid-evoked current and slow inactivation of ASIC1A, ASIC1B and ASIC3 (REF. 117) | Extracellular application117 | |

| Polyamines | Spermine | Increases ASIC1A-, ASIC1B- and ASIC1A–ASIC2A-mediated currents by shifting proton steady-state desensitization82–84 | Probably extracellular; interrupted by PcTx1 and extracellular mutations84 |

| Agmatine | Activates homomeric ASIC3 and heteromeric ASIC3–ASIC1B channels62,63 | Extracellular non-proton, ligand-sensing domain63 | |

| Cations | Ca2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Gd3+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Ba2+ | Inhibit various homomeric and heteromeric ASIC channels3,78,83,118–124 | Various. For example, Ca2+-dependent inhibition of ASIC1A was affected by mutating transmembrane region 2 and the extracellular domain123,124 |

| Other | Arachidonic acid | Increases sustained inward current80 | Unknown125 |

| Lactate | Potentiates current amplitude in response to acidosis79 | Indirect, chelates extracellular divalent ions79 | |

| Nitric oxide | Nitric oxide donors potentiate ASIC1A, ASIC1B, ASIC2B and ASIC3 homomers126 | Probably extracellular126 | |

| ATP | Increases pH sensitivity of ASIC3 homomers127 | Probably through purinergic P2X receptors127 | |

| Serotonin | Enhances ASIC3-sustained currents113 | Extracellular; depends on the non-proton, ligand-sensing domain113 | |

| Exogenous modulators | |||

| Toxins from venoms | PcTx1 | Desensitizes ASIC1A homomers64,128 and ASIC1A–ASIC2B heteromers78 | Extracellular proton-sensitive acidic pockets116 |

| APETx2 | Inhibits ASIC3 and ASIC3-containing heteromers129 | Unknown, probably extracellular129 | |

| MitTx | Activator of ASIC1A and ASIC1B homomers48 and enhances pH sensitivity of ASIC2A channels48 | Unknown extracellular binding site48 | |

| Mambalgin-1 | Inhibits currents mediated by ASIC1A and ASIC1B homomers, and ASIC1A–ASIC2A, ASIC1A–ASIC2B and ASIC1A–ASIC1B heteromers67 | Unknown67 | |

| NSAIDs | Flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, aspirin, salicylic acid, diclofenac | Reduce ASIC1A and ASIC3 currents130 | Unknown |

| Other | Amiloride (and derivatives such as DMA) | Reduces currents in all ASIC subtypes3 | Unknown. Several possible binding sites in the extracellular domain and pore131,132 |

| A-317567 | Inhibits endogenous acid-evoked ASIC currents in rat DRG neurons133 and mouse CNS neurons104 | Unknown | |

| GMQ | Activates ASIC3 at neutral pH62 | Extracellular non-proton, ligand-sensing domain62 | |

| Nafamostat | Inhibits ASIC1A and ASIC2A134 and inhibits ASIC3 initial phase transient current134 | Extracellular application; site of action unknown134 | |

| Arcaine | Agmatine analogue that activates ASIC3 channels63 | Extracellular non-proton, ligand sensing domain63 | |

ASIC, acid-sensing ion channel; DMA, 5-(N,N-dimethyl)-amiloride hydrochloride; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; GMQ, 2-guanidine-4-methylquinazoline; PcTx1, psalmotoxin 1; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Figure 1. Structure and function of ASIC1A.

a| The crystal structure of the chicken acid-sensing ion channel 1 (ASIC1) indicates that three subunits combine into a trimeric channel complex (different colours represent distinct ASIC1 subunits)30 b| Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from neurons in acute amygdala slices showing an absence of pH 5.6-evoked current in neurons lacking ASIC1A. c | ASICs are activated by extracellular protons (H+) and possibly other yet-to-be identified ligands, and are modulated by a number of other factors (TABLE 2). ASIC1A, schematized here, is permeable to cations, primarily Na+ and to a lesser degree Ca2+. Upon activation, an inward current depolarizes the cell membrane, which activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) and voltage-gated Na+ channels (VGSCs) and may contribute to NMDA receptor (NMDAR) activation through the release of the voltage-dependent Mg2+ blockade. Thus, Na+ and Ca2+ influx contributes to membrane depolarization, the generation of dendritic spikes and action potentials, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) activation and possibly influence other second-messenger pathways. In addition, a number of intracellular proteins have been suggested to regulate ASICs (see REF. 17 for recent review).

At sensory neuron terminals, protons and other endogenous (or exogenous) chemicals are thought to activate ASICs12,13 (FIG. 2; TABLE 2). It has also been suggested that ASICs respond to mechanical stimuli at these terminals, a hypothesis that stems from the close structural relationship between ASICs and the mechanosensitive channels in Caenorhabditis elegans33. Findings from a number of studies are consistent with the possibility that ASICs contribute to mechanosensation13,18,19. For example, ASIC2 was found in mechanosensitive structures in rodent skin and was implicated in touch sensation18. More recently, ASIC2 was implicated in blood pressure regulation by aortic baroreceptors34. In another recent study, genetically disrupting or pharmacologically inhibiting ASIC3 impaired the ability of light skin pressure to recruit cutaneous blood flow, which increased vulnerability to pressure ulcers35. Such observations suggest that ASICs may have a mechanosensory role. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these responses are not yet clear35. Not all studies investigating the role of ASICs in mechanosensation have detected ASIC-dependent effects36. Furthermore, unlike pH, mechanical stimulation has not been shown to directly gate any of the ASICs. Thus, unlike the related mechanosensitive channels, which can directly be gated by pressure33, the precise roles of ASICs in mechanosensation continue to be debated.

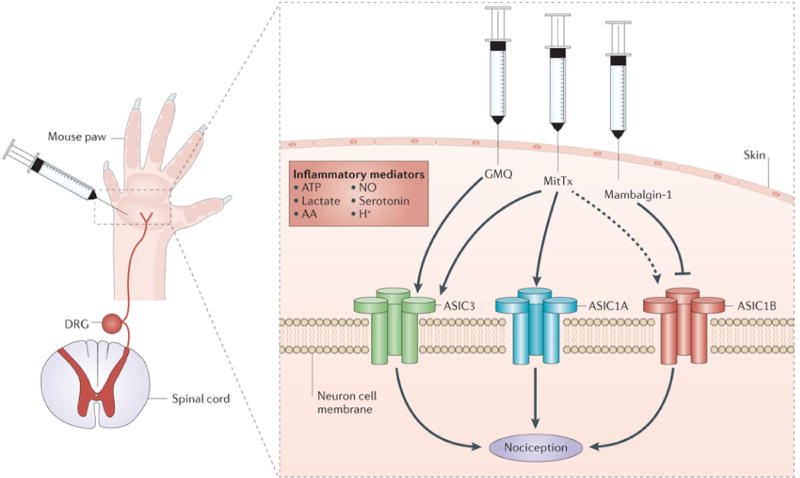

Figure 2. Roles for peripheral ASICs in pain.

Recent studies have taken advantage of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) agonists (2-guanidine-4-methylquinazoline (GMQ) and MitTx) and an antagonist (mambalgin-1) to clarify the roles of ASICs in pain. When injected into the mouse paw, the synthetic compound GMQ, which activates ASIC3, induced pain behaviours that were absent in ASIC3-knockout mice. These behaviours were not affected by ASIC1A disruption62. The Texas coral snake toxin, MitTx, evoked pain-related licking behaviour that depended on ASIC1A and, to a lesser degree, ASIC3 (REF. 48). ASIC1B was also activated by MitTx (dashed line), but its role in MitTx-evoked pain was not investigated. Mambalgin-1, a toxin from black mamba venom, blocked several combinations of ASIC subunits, and when it was injected into the mouse paw, it inhibited flick latency to heat through ASIC1B-containing channels67. In addition, another recent study indicated a role for the inflammatory mediator serotonin. Serotonin increased acid-evoked currents through ASIC3 and increased acid-evoked pain-behaviour in the mouse paw, which was attenuated by ASIC3 disruption113. A number of other inflammatory mediators have been suggested to modulate ASICs in pain, including arachidonic acid (AA), nitric oxide (NO), ATP and lactate (TABLE 2). DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

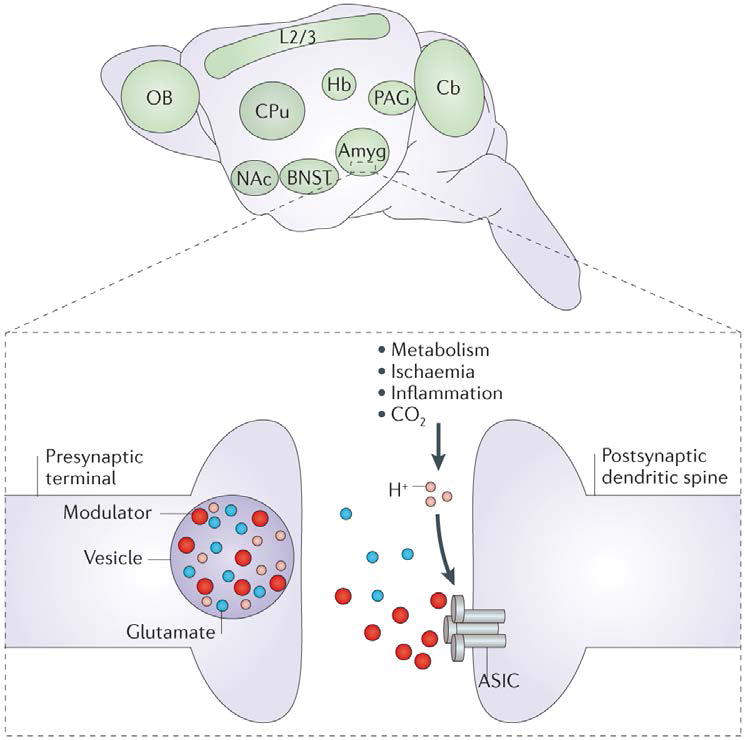

In CNS neurons, disrupting the gene encoding ASIC1A in mice eliminated most of the current evoked by extracellular acid, suggesting that ASIC1A is a critical channel subunit20,37,38 (FIG. 1b). At the subcellular level, ASIC1A was detected in the cell body, in dendrites and in postsynaptic dendritic spines20,39, suggesting that it has a role in synaptic physiology (FIG. 3). Supporting this possibility, whole-animal ASIC1A-knockout mice had reduced long-term potentiation, reduced acid-evoked Ca2 entry at dendritic spines and reduced dendritic spine number in hippocampal slices20,39. Also, in cultured hippocampal neurons from ASIC1A-knockout mice, an increase in presynaptic vesicle release was observed40. Consistent with these observations, a number of learning and memory-related phenotypes have been reported in ASIC1A-knockout mice20,21,38,41,42, in mice overexpressing human ASIC1A43 and in mice overexpressing mouse ASIC3 in the brain44. These phenotypes include differences in cued and contextual fear conditioning21,38,41–44, reduced eyeblink conditioning20 and a mild deficit in Morris water maze learning that was normalized with a more intensive training protocol20. In contrast to these observations, when murine ASIC1A expression in the CNS was disrupted by CRE-mediated excision via the nestin promoter, no deficits in Morris water maze learning or in hippocampal long-term potentiation were detected; however, deficits in fear conditioning were reported38. The reasons for the apparent differences in results with this cell-restricted knockout versus mice with unconditional ASIC1A disruption are not yet clear.

Figure 3. ASIC1A expression in the mouse brain.

Acid-sensing ion channel 1A (ASIC1A) is widely expressed in the mouse brain and is enriched in the amygdala (Amyg), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), periaqueductal grey (PAG), nucleus accumbens (NAc), caudate putamen (CPu), habenula (Hb), olfactory bulb (OB), cerebral cortex layer 2/3 (L2/3) and molecular layer of the cerebellum (Cb)21,102. ASIC1A localization in these brain regions has driven hypotheses about the behavioural roles of ASICs. At the subcellular level, ASIC1A has been detected in postsynaptic dendritic spines (inset), where, in one model, channel activation is caused by protons (H+) coming from acidic neurotransmitter-containing vesicles. Other pH changes, which are due to metabolism or disease, might also activate ASICs in the CNS. In addition, recent studies have highlighted the possibility that various endogenous factors, including neuropeptides and polyamines, modulate and/or activate ASICs (TABLE 2).

Compared with ASIC1A, much less is known about the other ASIC subunits in the brain. For example, ASIC2A and ASIC2B are expressed in the brain, but unlike ASIC1A these subunits are not required for acid-evoked currents in central neurons. However, in the absence of ASIC1A, ASIC2 subunits produced a small amount of current in brain neurons in response to very acidic pH (pH 4.0)45. Additionally, ASIC2A and ASIC2B interact with ASIC1A and can shift the pH sensitivity, desensitization kinetics and ion selectivity of acid-evoked currents27,28,45,46. Furthermore, unlike ASIC1A, ASIC2A can interact with postsynaptic density 95 (REF. 47), and ASIC2A was found to deliver ASIC1A-containing channel complexes to dendritic spines in cultured hippocampal slices47. Altering channel properties may produce significant behavioural effects. For example, expressing ASIC3 in the brain of transgenic mice increased the desensitization rate of acid-evoked currents and impaired fear conditioning44.

When expressed in heterologous cells, ASIC2A can form homomultimeric channels independently of ASIC1A; however, a role for ASIC2A or ASIC2B that is independent of ASIC1A has not yet been identified. Because the pH sensitivity of ASIC2A is outside what is considered physiological (for example, effector concentration for half-maximum response (EC50) ~ pH 4.5–4.9)27,28, ASIC2 homomers may be activated by something besides pH in vivo. A recent study found that an exogenous peptide, MitTx, greatly increased the pH-sensitivity of ASIC2A48, suggesting that it could act as a ‘coincidence detector’ that responds to pH in combination with other modulators48. Thus, a better understanding of ASIC2 localization and function vis-à-vis ASIC1A could be very informative.

The precise mechanisms by which ASICs are activated in the brain remain uncertain. One potential mechanism might involve protons released during neurotransmission by acidic (~pH 5.5) neurotransmitter-containing vesicles49 (FIG. 3). However, thus far, postsynaptic ASIC-dependent currents have not been detected during neurotransmission20,22,38. Protons generated by other sources, such as localized energy metabolism, might also contribute to ASIC activation50,51, as might the growing list of ASIC modulators10 (TABLE 2). The downstream mechanisms by which ASIC1A activation produces its effects also remain poorly defined. ASICs most probably influence neuronal function through membrane depolarization52,53, Ca2+ entry39 and through a number of downstream signalling cascades54 (FIG. 1c). Future studies should help to clarify the roles of ASICs in synaptic plasticity, learning, memory and behaviour.

ASICs and pain

A number of pain-causing stimuli, such as inflammation, lower extracellular pH. This observation hints at the existence of pH-sensitive receptors on nociceptive neurons and suggests that their activation causes pain. Possible candidate receptors include ASICs, which produce acid-evoked cation currents and are present both in the cell body and at terminals of peripheral nociceptive neurons (FIG. 2). Interestingly, ASIC1 and ASIC2 subunits are also present in areas of the CNS that are important in pain processing (FIG. 3). These findings have led investigators to hypothesize that ASICs contribute to pain. Support for this hypothesis has been gathered by genetically disrupting ASIC expression in mice and using pharmacological inhibitors12,13. However, early results were mixed. For example, ASIC3-knockout mice and mice with simultaneous disruption of ASIC1A, ASIC2 and ASIC3 showed increased pain-related behaviours55,56. By contrast, pharmacological blockade using the sea anemone peptide APETx2 and genetic knockdown of Asic3 decreased pain-related behaviours57. In addition, ASIC1A-knockout mice showed changes in some pain behaviours but not in others58,59. Furthermore, inhibiting ASIC1A in the CNS, but not the peripheral nervous system (PNS) reduced pain behaviours60,61. Such mixed results have raised important questions. Do ASICs really promote pain? If so, which subunits transmit the nociceptive signals? Do ASICs contribute to pain pathways in the CNS or the PNS, or both? A series of recent studies address these questions.

Strong evidence that activating ASIC3 is sufficient to cause pain was provided by a small molecule, 2-guani-dine-4-methylquinazoline (GMQ). GMQ was found to bind ASIC3 at a site that is distinct from its acid-sensing domain and to open the channel at neutral pH. Importantly, injecting GMQ into the mouse paw triggered pain behaviours in wild-type but not Asic3−/− mice (FIG. 2). GMQ is a synthetic molecule, but the authors demonstrated that agmatine, a related endogenous polyamine, binds to the same site on ASIC3 and causes pain behaviour62. Interestingly, agmatine also interacted with other inflammatory signals to increase ASIC3-dependent currents and pain63. These data indicate the existence of non-proton ASIC3 activators and suggest that endogenous molecules may activate ASICs to cause pain (TABLE 2). It is not yet clear whether any endogenous polyamines reach the high levels (~10 mM) that would be necessary to activate ASIC3. Polyamines are known to accumulate in synaptic and dense core vesicles, raising the possibility that these molecules might activate ASIC3 during synaptic transmission62.

Experiments with a peptide component (MitTx) in the venom of the Texas coral snake (Micrurus tener tener) further indicated roles for ASIC1, ASIC2 and ASIC3 in pain. MitTx triggered persistent activation of ASIC1A and ASIC1B homomultimers in cultured somatosensory neurons, and at higher concentrations it also activated ASIC3 (REF. 48). Interestingly, although MitTx did not activate ASIC2A at neutral pH, it potentiated its proton sensitivity more than 100-fold, suggesting that a similar, as-yet-unidentified endogenous compound might facilitate ASIC2A responses to physiological changes in pH. The authors speculated that ASIC2A might function as a co-incidence detector for pH and some as-yet-unidentified modulator. Injecting purified MitTx into the hind paw of mice elicited pain behaviours that were significantly diminished by ASIC1A disruption (FIG. 2). Disrupting ASIC3 also attenuated the pain response when higher MitTx concentrations were injected. These findings indicated that MitTx elicits pain through ASIC1A, and to a smaller degree ASIC3, in peripheral nociceptive neurons48.

Recent evidence also points to roles for ASICs in pain processing in the CNS. A peptide (psalmotoxin 1 (PcTx1)) in the venom of the Trinidad chevron tarantula (Psalmopoeus cambridgei) inhibits ASIC1A homomultimeric channel activity64. Intrathecal injection of PcTx1 reduced thermal, mechanical, chemical, inflammatory and neuropathic pain in rodents60,61. Interestingly, this peptide also raised endogenous Met-enkephalin levels in cerebrospinal fluid60. However, a mechanistic link between ASIC1A and Met-enkephalin has not yet been elucidated.

In the spinal cord, ASIC1A and ASIC2A levels were increased by peripheral inflammation, suggesting a role for ASICs in central sensitization of pain61,65. Consistent with this possibility, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) promoted ASIC1A cell surface expression via phosphorylation at Ser-25 through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase–protein kinase B (also known as AKT1) pathway66. Furthermore, genetically disrupting ASIC1A reduced mechanical hyperalgesia elicited by intrathecal BDNF injection66. Taken together, these studies suggest that ASICs in the CNS contribute to pain processing. Although the mechanisms of ASIC action in central pain circuits are not yet clear, it is possible that ASICs may alter neuron excitability or synaptic plasticity.

Perhaps the strongest evidence to date that inhibiting ASICs in either the CNS or the PNS reduces pain was obtained using black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis) venom, which contains a three-finger peptide (mambalgin-1) that blocks ASIC currents. Mambalgin-1 inhibited current from ASIC1A and ASIC1B homomers as well as from heteromers of ASIC1A–ASIC2A, ASIC1A–ASIC2B or ASIC1A–ASIC1B. Importantly, mambalgin-1 inhibited pain in mice when injected either centrally or peripherally. Intrathecal or intracerebroventricular injection reduced pain responses in acute thermal and inflammatory pain models (carrageenan and formalin), and injecting mambalgin-1 peripherally into the paw reduced acute thermal pain (FIG. 2) and inflammatory hyperalgesia. Interestingly, the central analgesic effects were dependent on ASIC1A and ASIC2A, whereas the peripheral analgesic effects were dependent on ASIC1B. Importantly, unlike opioid analgesics and PcTx1, mam-balgin-1 elicited minimal analgesic tolerance, suggesting that there is potential for more long-lasting analgesia. Also, unlike opioids, mambalgin-1 produced no respiratory suppression. These observations suggest that mambalgin-like ASIC antagonists may have distinct advantages over opioids for pain alleviation67.

These studies highlight the possibility that the PNS and CNS use different combinations of ASIC subunits to mediate pain. Optimum signalling through ASICs at different anatomical sites may require different channel properties, and channel activity might be optimized through different combinations of ASIC subunits and ASIC modulators. Importantly, these studies identify ASICs as potential targets for new pain medications. The ASIC inhibitor amiloride (which also affects a number of non-ASIC targets) is approved for use in humans, and a few small translational experiments have demonstrated its potential for reducing cutaneous pain and migraine68–70.

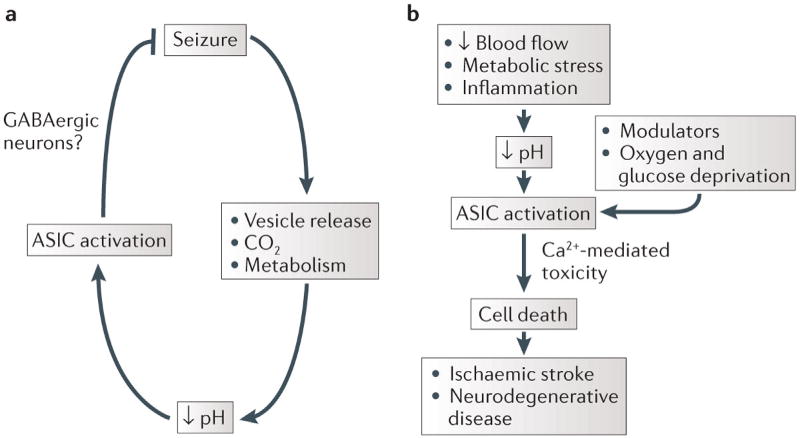

ASICs, neurotoxicity and neurological diseases

A number of neurological diseases involve acidosis, arising from several possible sources, including ischaemia, inflammation, metabolism and synaptic transmission50 (FIG. 4). Extreme or prolonged acidosis kills neurons, and there is growing evidence that ASICs mediate acid-induced toxicity in the CNS. Some of the earliest evidence for ASICs in acidosis-induced injury came from cell culture and mouse models of ischaemia37,71. Disrupting ASIC1A or inhibiting ASICs with amiloride or PcTx1 reduced acidosis-induced cell death in cultured neurons37,71. Moreover, these ASIC manipulations substantially reduced infarct volume in rats and mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion37,72.

Figure 4. Contrasting roles of brain pH and ASICs in seizures and neurotoxicity.

Reduced brain pH can be protective or damaging. a | The ability of acidosis to inhibit seizures is thought to be acid-sensing ion channel 1A (ASIC1A)-mediated, possibly owing to abundant ASIC1A expression in GABAergic neurons52,95,96. b | Accumulating evidence suggests that acidosis potentiates cell death, which contributes to ischaemic stroke and neurodegenerative disease and that this depends on ASIC1A. Other factors, such as oxygen and glucose depletion, inflammation and other modulators are likely to play important parts in these processes.

Subsequent studies have suggested that a number of other neurodegenerative diseases lead to localized acidosis and that disrupting ASICs pharmacologically or genetically may be protective. In addition to ischaemic stroke, ASICs have now been implicated in multiple sclerosis73, Huntington’s disease74, Parkinson’s disease75 and spinal cord injury76. TABLE 3 lists these studies, many of which have been previously reviewed14,15. Below, we review some recent advances in understanding how different ASIC subunits and ASIC modulators might contribute to neurotoxicity.

Table 3.

ASICs and neurological disease

| Disease | Role of pH | Role of ASICs |

|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic stroke |

|

|

| Multiple sclerosis | The EAE model induces spinal cord acidosis73 |

|

| Huntington’s disease (HD) | Increased levels of lactate in the brain have been shown in patients with HD as well as in an animal model of HD139,140 | In a mouse model of HD, depletion of ASIC1A or treatment with amiloride or benzamil reduced polyglutamine aggregation74 |

| Parkinson’s disease | Patients with Parkinson’s disease exhibit increased brain lactate levels141 | |

| Migraine | ||

| Spinal cord injury | ||

| Glioblastoma |

|

|

| Epilepsy |

|

ASIC, acid-sensing ion channel; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; ENaC, epithelial NA+ channel; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; PcTx1, psalmotoxin 1; PICK1, protein interacting with C kinase 1 (also known as PRKCA-binding protein); SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Much of the previous work on ASICs and neurotoxicity focused on ASIC1A homomultimeric channels and their ability to conduct Ca2+ and induce Ca2+-mediated toxicity37,39,71. Building on these observations, a recent paper observed that constitutive endocytosis of ASIC1A in a clathrin- and dynamin-dependent manner protected cells against acid-induced cell death77. Potential roles of the other ASICs, particularly ASIC2B, have been uncertain, as ASIC2B homomers do not form pH-sensitive channels7,27. A recent study suggested an important role for ASIC2B in acidosis-induced neuron death78. This study found that heteromultimeric channels composed of ASIC2B–ASIC1A were Ca2+-permeable and sensitive to PcTx1, similar to ASIC1A homomeric channels. Ba2+ was subsequently shown to inhibit these ASIC2B–ASIC1A channels and attenuate acidosis-induced cell death78, suggesting that targeting ASIC2B, as well as ASIC1A, may prevent acid-induced neurotoxicity.

In addition to causing acidosis, brain injury results in the release of a number of endogenous chemicals that can modulate ASICs, including lactate, arachidonic acid and dynorphin (TABLE 2). These and other factors may boost ASIC currents and their associated toxicity54,79–81. Several studies have highlighted the importance of ASIC modulators in neurotoxicity and identified potential new leads for therapeutic compounds that may target ASICs.

The abundance of the endogenous polyamine spermine in the CNS and its interaction with ASICs could have important consequences for neurotoxicity82,83. In a recent study, exogenous spermine was delivered to the brain through an intracerebroventricular cannula before middle cerebral artery occlusion84. As predicted, spermine increased infarct volume, but this toxicity-promoting effect was significantly reduced in ASIC1A-knockout mice. Consistent with this result, blocking the production of endogenous spermine also protected against ischaemic damage in an ASIC1A-dependent manner. These observations suggest that the toxic effects of spermine, agmatine and other ASIC modulators might be due to their effects on ASICs and highlight the possibility that ASIC modulators might be valuable therapeutic targets.

Interestingly, several traditional Chinese medicines were suggested to produce their neuroprotective effects through ASICs85–88. Three such compounds (puerarin, sophocarpine and ginsenoside-Rd), which were previously known to protect against damage caused by middle cerebral artery occlusion, all interfered with ASIC1A function by reducing current amplitude, increasing channel desensitization or decreasing ASIC1A expression85–88. It will be interesting to see whether the neuroprotective effects of these compounds depend on ASICs, whether they are effective in other models of neurotoxicity and whether they have additional analgesic or behavioural effects depending on the ASIC subtype they target. They might also be valuable lead compounds, as their safety has largely been established already.

ASICs and glioblastoma

Glioblastoma cells exhibit constitutively active amiloride- and PcTx1-sensitive cation currents. These currents are thought to be mediated by hybrid channels comprised of ASIC1A and other DEG– ENaCs89–92. Recently, the potential role of ASICs in glioblastoma was probed by targeting ASIC1A in cultured human glioma cells. The ASIC inhibitor PcTx1 inhibited cell migration and cell cycle progression. Similarly, the amiloride analogue benzamil caused cell cycle arrest93. These results suggest the possibility that pH and ASIC1A activity may be crucial in glioblastoma pathophysiology. They further suggest the intriguing possibility that targeting pH and ASICs might inhibit the growth and spread of some cancers.

ASICs and epilepsy

Another neurological disease in which ASICs have been suggested to play a part is epilepsy94. Seizures reduce brain pH, and it has been known for decades that acidosis inhibits seizures. Thus, one potential reason that most seizures are self-limited is because of feedback inhibition mediated by low pH (FIG. 4). ASIC1A has been implicated in this feedback mechanism52, as deleting the gene encoding ASIC1A in mice increased the duration of chemoconvulsant-induced seizures, although it did not affect seizure threshold. Conversely, overexpressing ASIC1A in mice, produced the opposite effect and inhibited seizures. Consistent with a role in terminating seizures, loss of ASIC1A reduced postictal depression, which has been thought to underlie seizure termination. The ability of acidic pH to suppress seizure-like activity was reduced in hippocampal slices from the ASIC1A-knockout mice. Furthermore, the ability of CO2 inhalation and associated acidosis to inhibit seizure-induced lethality was lost in these ASIC1A-knockout mice. Following high-dose pentylenetetrazol administration, wild-type mice survived when breathing 10% CO2, whereas the ASIC1A-knockout mice did not. These studies suggest that the prolonged seizures of status epilepticus and the associated increase in seizure-related mortality might result from ASIC1A dysfunction52. Thus, ASIC1A might be a novel target for treating epilepsy or status epilepticus.

It is still unclear how ASIC1A inhibits seizure activity. The acid-evoked current in inhibitory neurons might be responsible (FIG. 4), as in the hippocampus, ASIC1A is more abundant in GABAergic neurons than in glutamatergic neurons52,95,96. It is also puzzling that other studies have raised the possibility that ASIC1A might have the opposite effect and increase seizure activity15. For example, amiloride inhibited seizures in several animal models, although it is not clear whether those effects were due to amiloride’s inhibition of ASICs or of other molecules such as the Na+/H+ exchanger15,97–99.

More work is needed to determine whether the effects of ASIC1A on seizures in rodents also occur in humans. A step in this direction was recently taken by a human genetic study that suggested an association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ASIC1 and temporal lobe epilepsy100.

ASICs and psychiatric disease

Psychiatric illnesses are extremely common, with an estimated half of all Americans surveyed experiencing at least one psychiatric illness during their lifetime101. However, our understanding of the molecular, physiological and neuroanatomical bases of these disorders is remarkably limited. Advances in psychiatric genetics have drawn increasing attention to the possibility that psychiatric illness might result from synaptic dysfunction. The synaptic localization of ASICs and their prominent expression in brain structures underlying emotion, cognition and behaviour (including the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, habenula, nucleus accumbens and periaqueductal grey (FIG. 3)), suggest that ASICs are well positioned to influence psychiatric symptoms20,21,39,102. The possibility that ASICs have a role in brain function and behaviour is supported by initial studies of the effects of ASIC1A disruption in mice on synaptic plasticity, neurophysiology and models of anxiety and depression. ASIC1A-knockout mice exhibited deficits in cued and contextual fear conditioning as well as in unconditioned fear behaviours, such as predator odour-evoked freezing, open-field centre-avoidance and acoustic startle responses20,21,102.

Another role for ASICs in fear-related behaviours was recently identified, which linked ASIC1A more closely to brain pH changes in vivo. CO2 inhalation rapidly lowers pH in the brain and has long been known to trigger fear and panic attacks in humans42,103. Paralleling the CO2 effects in humans, CO2 inhalation also triggered fear-like behaviours in mice42. Importantly, eliminating or inhibiting ASIC1A markedly reduced these responses. Likewise, buffering the acidosis with bicarbonate reduced CO2-evoked freezing behaviour. At least one anatomical site of ASIC1A action in these behaviours was the amygdala; localized ASIC1A expression in the amygdala restored CO2-induced freezing in ASIC1A-knockout mice to near wild-type levels. Moreover, the freezing induced by CO2 was reproduced by injecting acidic solution directly into the amygdala of wild-type but not ASIC1A-knockout mice. These observations provide some of the clearest evidence so far that ASIC activation in the brain depends on pH. From these data, one might also speculate that ASICs in the amygdala might help to prevent suffocation by inducing active defence responses. Rising CO2 heralds the potential threat of suffocation. Thus, the ability to detect CO2 and elicit prompt defensive action could be life-saving. From an evolutionary perspective, it is interesting to imagine that this might be a key role for ASICs.

In addition to its role in fear behaviour, ASIC1A was found to contribute to depression-related behaviours in mice. Genetically or pharmacologically disrupting ASIC1A reduced depression-related behaviours in the forced swim test, tail suspension test and after experiencing unpredictable mild stress104. Interestingly, the antidepressant-like effect of inhibiting ASIC1A was independent of serotonin depletion and also independent of several currently used antidepressants, including fluoxetine, desipramine and bupropion. These findings raise the possibility that inhibiting ASIC1A might reduce depression through a novel mechanism of action — a potentially exciting possibility, given that standard antidepressants are ineffective for many patients. More studies linking ASICs to depression and clarifying the mechanisms may mitigate some of the barriers to developing ASIC inhibitors for depression therapy.

So far, only a handful of genetic studies have evaluated the potential link between ASICs and human psychiatric illness. The largest of these studies examined the relationship between SNPs in ASIC1 with anxiety disorders and depression. In this twin-pair study that included 589 cases versus 539 controls, no statistically significant association was identified. The data did suggest a possible link to depression, but it was not significant when corrected for multiple comparisons105. In another study, a quantitative trait locus for anxiety-related behaviours in mice was found to be homologous to the human chromosomal region 12q13, which contains ASIC1. Interestingly, this same region was linked to panic disorder in humans106.

Besides these notable examples, a few small genome-wide association studies have suggested associations between SNPs in ASIC2 with panic disorder, lithium-response in bipolar disorder and citalopram-response in major depressive disorder107–109. In addition, the ASIC2-containing locus has been associated with autism110. Although these initial genetic findings are encouraging, they are not definitive. Stronger genetic associations to human illness might come from high-throughput, genome-wide sequencing or from other rapidly progressing technological advances in human genetics research. Expanding the search to include genes that regulate pH or modulate ASIC function might also be beneficial to the search for genetic variations affecting ASICs.

Together, these studies suggest the possibility that abnormal ASIC function might contribute to psychiatric illness and that targeting ASICs may be therapeutically beneficial. The prominent behavioural effects of ASIC1A raise questions about the role of brain pH in behaviour. For example, does pH change in the brain while conducting normal cognitive tasks? Might these pH changes produce important behavioural or cognitive effects? Moreover, might targeting brain pH provide a novel therapeutic approach? Better methods for measuring brain pH in animals and in humans may help to answer some of these questions. Recently, an MRI study using T1 relaxation in the rotating frame (T1ρ) suggested that the visual cortex may become acidic in response to a visual stimulation with a flashing checkerboard pattern111. This initial example is consistent with the possibility that pH may fluctuate during routine brain activity. Tools such as this could greatly improve our understanding of the roles of pH in the brain in behaviour and disease.

Summary and future directions

There is now a substantial and growing body of research in animal models that implicates ASICs in various diseases. However, it will be important to determine how our current knowledge of ASICs translates to humans. One path to translation would be to find genetic associations between ASICs and human traits or diseases. Another path is to determine whether ASIC inhibitors produce effects in humans; along this line, several beneficial effects of amiloride have been recently reported68–70,112. More knowledge of brain pH dynamics is also needed and may require improved methods to measure and manipulate pH in vivo111. Last, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of ASIC action will help to clarify how inhibiting or potentiating these channels affects physiology, pathophysiology and behaviour. This knowledge will help to develop new therapies targeting ASICs and ASIC modulators.

Acknowledgments

J.A.W. is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (Merit Award), the National Institutes of Mental Health (1R01MH085724 01) and a McKnight Neuroscience of Brain Disorders Award.

Glossary

- Degenerin–epithelial Na+ channel family

(DEG–ENaC family). A family of ion channels that includes acid-sensing ion channels and is characterized by two transmembrane domains, a relatively large cysteine-rich extracellular domain and several highly conserved amino acid sequence motifs

- Nociception

Refers to detection of painful and injurious stimuli and translation into a neuronal signal

- Mechanosensation

Refers to detection of mechanical stimuli and translation into a neuronal signal

- Acidosis

A physiological state characterized by acidic pH (high H+ concentration)

- Alkalosis

A physiological state characterized by basic pH (low H+ concentration)

- Baroreceptors

Receptors that are sensitive to changes in blood pressure

- Long-term potentiation

A long-lasting, activity-dependent strengthening of synaptic transmission

- Postictal depression

The reduction in electroencephalographic activity that occurs immediately after a seizure

- Pentylenetetrazol

A GABA receptor antagonist used to elicit seizures

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gruol DL, Barker JL, Huang LY, MacDonald JF, Smith TG., Jr Hydrogen ions have multiple effects on the excitability of cultured mammalian neurons. Brain Res. 1980;183:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishtal O, Pidoplichko V. A receptor for protons in the nerve cell membrane. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2325–2327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature. 1997;386:173–177. doi: 10.1038/386173a0. This study reports the cloning and identification of ASIC1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price MP, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. Cloning and expression of a novel human brain Na+ channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7879–7882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldmann R, Champigny G, Voilley N, Lauritzen I, Lazdunski M. The mammalian degenerin MDEG, an amiloride-sensitive cation channel activated by mutations causing neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10433–10436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Añoveros J, Derfler B, Neville-Golden J, Hyman BT, Corey DP. BNaC1 and BNaC2 constitute a new family of human neuronal sodium channels related to degenerins and epithelial sodium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1459–1464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lingueglia E, et al. A modulatory subunit of acid sensing ion channels in brain and dorsal root ganglion cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29778–29783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. H+-gated cation channels: neuronal acid sensors in the NaC/DEG family of ion channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:418–424. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherwood TW, Frey EN, Askwith CC. Structure and activity of the acid-sensing ion channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C699–C710. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00188.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu XP, Papasian CJ, Wang JQ, Xiong ZG. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channels: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2011;3:288–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunder S, Chen X. Structure, function, and pharmacology of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs): focus on ASIC1a. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2010;2:73–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deval E, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs): pharmacology and implication in pain. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;128:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wemmie JA, Price MP, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channels: advances, questions and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu XP, Xiong ZG. Physiological and pathological functions of acid-sensing ion channels in the central nervous system. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:263–271. doi: 10.2174/138945012799201685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong ZG, Pignataro G, Li M, Chang SY, Simon RP. Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) as pharmacological targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sluka KA, Winter OC, Wemmie JA. Acid-sensing ion channels: a new target for pain and CNS diseases. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:693–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zha XM. Acid-sensing ion channels: trafficking and synaptic function. Mol Brain. 2013;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price MP, et al. The mammalian sodium channel BNC1 is required for normal touch sensation. Nature. 2000;407:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35039512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price MP, et al. The DRASIC cation channel contributes to the detection of cutaneous touch and acid stimuli in mice. Neuron. 2001;32:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wemmie JA, et al. The acid-activated ion channel ASIC contributes to synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. Neuron. 2002;34:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00661-x. This study describes the electrophysiological and behavioural effects of genetically disrupting ASIC1A in mice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wemmie JA, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 1 is localized in brain regions with high synaptic density and contributes to fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5496–5502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05496.2003. This paper describes the expression pattern of ASIC1A in the mouse brain and implicates ASIC1A in fear conditioning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez de la Rosa D, et al. Distribution, subcellular localization and ontogeny of ASIC1 in the mammalian central nervous system. J Physiol. 2003;546:77–87. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson CJ, Eckert SP, McCleskey EW. Acid-evoked currents in cardiac sensory neurons: a possible mediator of myocardial ischemic sensation. Circ Res. 1999;84:921–928. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaunay A, et al. Human ASIC3 channel dynamically adapts its activity to sense the extracellular pH in both acidic and alkaline directions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13124–13129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120350109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang WZ, et al. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channel currents, acid-induced increase of intracellular Ca2+, and acidosis-mediated neuronal injury by intracellular pH. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29369–29378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Gründer S. Permeating protons contribute to tachyphylaxis of the acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a. J Physiol. 2007;579:657–670. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hesselager M, Timmermann DB, Ahring PK. pH-dependency and desensitization kinetics of heterologously expressed combinations of ASIC subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11006–11015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson CJ, et al. Heteromultimerics of DEG/ENaC subunits form H+-gated channels in mouse sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2338–2343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032678399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassilana F, et al. The acid-sensitive ionic channel subunit ASIC and the mammalian degenerin MDEG form a heteromultimeric H+-gated Na+ channel with novel properties. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28819–28822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, Gouaux E. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. This paper identifies the crystal structure of chicken ASIC1 minus the N and C termini. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature. 2009;460:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature08218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zha XM, et al. Oxidant regulated inter-subunit disulfide bond formation between ASIC1a subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3573–3578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813402106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bianchi L. Mechanotransduction: touch and feel at the molecular level as modeled in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:254–271. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-8009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Y, et al. The ion channel ASIC2 is required for baroreceptor and autonomic control of the circulation. Neuron. 2009;64:885–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fromy B, Lingueglia E, Sigaudo-Roussel D, Saumet JL, Lazdunski M. Asic3 is a neuronal mechanosensor for pressure-induced vasodilation that protects against pressure ulcers. Nature Med. 2012;18:1205–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roza C, et al. Knockout of the ASIC2 channel in mice does not impair cutaneous mechanosensation, visceral mechanonociception and hearing. J Physiol. 2004;558:659–669. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong ZG, et al. Neuroprotection in ischemia: blocking calcium-permeable acid-sensing ion channels. Cell. 2004;118:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.026. This is one of the earliest studies showing that targeting ASIC1A in a model of ischaemic stroke has a neuroprotective effect. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu PY, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel-1a is not required for normal hippocampal LTP and spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1828–1832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4132-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zha XM, Wemmie JA, Green SH, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channel 1a is a postsynaptic proton receptor that affects the density of dendritic spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16556–16561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608018103. The authors of this study detected ASIC1A in dendritic spines and implicated it in synaptic plasticity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho JH, Askwith CC. Presynaptic release probability is increased in hippocampal neurons from ASIC1 knockout mice. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:426–441. doi: 10.1152/jn.00940.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coryell MW, et al. Restoring acid-sensing ion channel-1a in the amygdala of knock-out mice rescues fear memory but not unconditioned fear responses. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13738–13741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3907-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziemann AE, et al. The amygdala is a chemosensor that detects carbon dioxide and acidosis to elicit fear behavior. Cell. 2009;139:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.029. This study implicates ASIC1A in CO2-evoked fear behaviours and describes a chemosensory role for ASIC1A in the amygdala. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wemmie J, et al. Overexpression of acid-sensing ion channel 1a in transgenic mice increases fear-related behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3621–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308753101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vralsted VC, et al. Expressing acid-sensing ion channel 3 in the brain alters acid-evoked currents and impairs fear conditioning. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:444–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Askwith CC, Wemmie JA, Price MP, Rokhlina T, Welsh MJ. ASIC2 modulates ASIC1 H+-activated currents in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;279:18296–18305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baron A, et al. Protein kinase C stimulates the acid-sensing ion channel ASIC2a via the PDZ domain-containing protein PICK1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50463–50468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zha XM, et al. ASIC2 subunits target acid-sensing ion channels to the synapse via an association with PSD-95. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8438–8446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1284-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bohlen CJ, et al. A heteromeric Texas coral snake toxin targets acid-sensing ion channels to produce pain. Nature. 2011;479:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature10607. The venom peptide MitTx activates ASIC1A in peripheral neurons to cause pain, and it increases the pH sensitivity of ASIC2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wemmie JA, Zha X, Welsh MJ. In: Structural and Functional Organization of the Synapse. Hell JW, Ehlers MD, editors. Springer; 2008. pp. 661–681. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng WZ, Xu TL. Proton production, regulation and pathophysiological roles in the mammalian brain. Neurosci Bull. 2012;28:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wemmie JA. Neurobiology of panic and pH chemosensation in the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:475–483. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/jwemmie. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziemann AE, et al. Seizure termination by acidosis depends on ASIC1a. Nature Neurosci. 2008;11:816–822. doi: 10.1038/nn.2132. This paper describes a role for ASICs in seizures and suggests that ASIC1A promotes seizure termination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vukicevic M, Kellenberger S. Modulatory effects of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) on action potential generation in hippocampal neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C682–C690. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00127.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao J, et al. Coupling between NMDA receptor and acid-sensing ion channel contributes to ischemic neuronal death. Neuron. 2005;48:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen CC, et al. A role for ASIC3 in the modulation of high-intensity pain stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8992–8997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122245999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang S, et al. Simultaneous disruption of mouse ASIC1a, ASIC2 and ASIC3 genes enhances cutaneous mechanosensitivity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deval E, et al. ASIC3, a sensor of acidic and primary inflammatory pain. EMBO J. 2008;27:3047–3055. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Page AJ, et al. The ion channel ASIC1 contributes to visceral but not cutaneous mechanoreceptor function. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1739–1747. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walder RY, et al. ASIC1 and ASIC3 play different roles in the development of hyperalgesia after inflammatory muscle injury. J Pain. 2010;11:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mazzuca M, et al. A tarantula peptide against pain via ASIC1a channels and opioid mechanisms. Nature Neurosci. 2007;10:943–945. doi: 10.1038/nn1940. This study suggests that pharmacologically and genetically inhibiting ASIC1A has analgesic effects by increasing endogenous opioid levels. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duan B, et al. Upregulation of acid-sensing ion channel ASIC1a in spinal dorsal horn neurons contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11139–11148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3364-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu Y, et al. A nonproton ligand sensor in the acid-sensing ion channel. Neuron. 2010;68:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.001. This paper suggests that GMQ directly activates ASIC3 on peripheral neurons to cause pain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li WG, Yu Y, Zhang ZD, Cao H, Xu TL. ASIC3 channels integrate agmatine and multiple inflammatory signals through the nonproton ligand sensing domain. Mol Pain. 2010;6:88. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Escoubas P, et al. Isolation of a tarantula toxin specific for a class of proton-gated Na+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25116–25121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu LJ, et al. Characterization of acid-sensing ion channels in dorsal horn neurons of rat spinal cord. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43716–43724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duan B, et al. PI3-kinase/Akt pathway-regulated membrane insertion of acid-sensing ion channel 1a underlies BDNF-induced pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6351–6363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4479-11.2012. This paper demonstrates that increased ASIC1A surface expression in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord may contribute to the central sensitization to pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diochot S, et al. Black mamba venom peptides target acid-sensing ion channels to abolish pain. Nature. 2012;490:552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature11494. This study strongly suggests that blocking ASICs with black mamba venom toxins reduces pain and that the effect is not opioid-dependent. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holland PR, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 1: a novel therapeutic target for migraine with aura. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:559–563. doi: 10.1002/ana.23653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ugawa S, et al. Amiloride-blockable acid-sensing ion channels are leading acid sensors expressed in human nociceptors. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1185–1190. doi: 10.1172/JCI15709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones NG, Slater R, Cadiou H, McNaughton P, McMahon SB. Acid-induced pain and its modulation in humans. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10974–10979. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2619-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yermolaieva O, Leonard AS, Schnizler MK, Abboud FM, Welsh MJ. Extracellular acidosis increases neuronal cell calcium by activating acid-sensing ion channel 1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6752–6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isaev NK, et al. Role of acidosis, NMDA receptors, and acid-sensitive ion channel 1a (ASIC1a) in neuronal death induced by ischemia. Biochemistry. 2008;73:1171–1175. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908110011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Friese MA, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel-1 contributes to axonal degeneration in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system. Nature Med. 2007;13:1483–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm1668. This study implicates ASIC1A in a mouse model of neuroinflammatory disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong HK, et al. Blocking acid-sensing ion channel 1 alleviates Huntington’s disease pathology via an ubiquitin-proteasome system-dependent mechanism. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3223–3235. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arias RL, et al. Amiloride is neuroprotective in an MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu R, et al. Role of acid-sensing ion channel 1a in the secondary damage of traumatic spinal cord injury. Ann Surg. 2011;254:353–362. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822645b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zeng WZ, et al. Molecular mechanism of constitutive endocytosis of acid-sensing ion channel 1a and its protective function in acidosis-induced neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7066–7078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5206-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sherwood TW, Lee KG, Gormley MG, Askwith CC. Heteromeric acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) composed of ASIC2b and ASIC1a display novel channel properties and contribute to acidosis-induced neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9723–9734. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1665-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Immke DC, McCleskey EW. Lactate enhances the acid-sensing Na+ channel on ischemia-sensing neurons. Nature Neurosci. 2001;4:869–870. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Allen NJ, Attwell D. Modulation of ASIC channels in rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons by ischaemia-related signals. J Physiol. 2002;543:521–529. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hauser KF, et al. Pathobiology of dynorphins in trauma and disease. Front Biosci. 2005;10:216–235. doi: 10.2741/1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kindy MS, Hu Y, Dempsey RJ. Blockade of ornithine decarboxylase enzyme protects against ischemic brain damage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:1040–1045. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Babini E, Paukert M, Geisler HS, Gründer S. Alternative splicing and interaction with di- and polyvalent cations control the dynamic range of acid-sensing ion channel 1 (ASIC1) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41597–41603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duan B, et al. Extracellular spermine exacerbates ischemic neuronal injury through sensitization of ASIC1a channels to extracellular acidosis. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2101–2112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4351-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang Y, et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of puerarin in middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced brain infarction in rats. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:9. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gu L, Yang Y, Sun Y, Zheng X. Puerarin inhibits acid-sensing ion channels and protects against neuron death induced by acidosis. Planta Med. 2010;76:583–588. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang Y, et al. Ginsenoside-Rd attenuates TRPM7 and ASIC1a but promotes ASIC2a expression in rats after focal cerebral ischemia. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0916-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yifeng M, et al. Neuroprotective effect of sophocarpine against transient focal cerebral ischemia via down-regulation of the acid-sensing ion channel 1 in rats. Brain Res. 2011;1382:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Berdiev BK, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels in malignant gliomas. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15023–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bubien JK, et al. Cation selectivity and inhibition of malignant glioma Na+ channels by Psalmotoxin 1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1282–C1291. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00077.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vila-Carriles WH, et al. Surface expression of ASIC2 inhibits the amiloride-sensitive current and migration of glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19220–19232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kapoor N, et al. Knockdown of ASIC1 and epithelial sodium channel subunits inhibits glioblastoma whole cell current and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24526–24541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rooj AK, et al. Glioma-specific cation conductance regulates migration and cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4053–4065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.311688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Biagini G, Babinski K, Avoli M, Marcinkiewicz M, Séguéla P. Regional and subunit-specific downregulation of acid-sensing ion channels in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:45–58. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weng JY, Lin YC, Lien CC. Cell type-specific expression of acid-sensing ion channels in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6548–6558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0582-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bolshakov KV, et al. Characterization of acid-sensitive ion channels in freshly isolated rat brain neurons. Neuroscience. 2002;110:723–730. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ali A, Pillai KP, Ahmad FJ, Dua Y, Vohora D. Anticonvulsant effect of amiloride in pentetrazole-induced status epilepticus in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58:242–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.N’Gouemo P. Amiloride delays the onset of pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1222:230–232. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Luszczki JJ, Sawicka KM, Kozinska J, Dudra-Jastrzebska M, Czuczwar SJ. Amiloride enhances the anticonvulsant action of various antiepileptic drugs in the mouse maximal electroshock seizure model. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lv RJ, et al. ASIC1a polymorphism is associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2011;96:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Coryell M, et al. Targeting ASIC1a reduces innate fear and alters neuronal activity in the fear circuit. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Drury AN. The percentage of carbon dioxide in the alveolar air, and the tolerance to accumulating carbon dioxide in case of co-called “irritable heart”. Heart. 1918;7:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Coryell MW, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel-1a in the amygdala, a novel therapeutic target in depression-related behavior. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5381–5388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0360-09.2009. This study shows that loss of ASIC1A has antidepressant-like effects in multiple mouse models of depression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hettema JM, et al. Lack of association between the amiloride-sensitive cation channel 2 (ACCN2) gene and anxiety spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;18:73–79. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3282f08a2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Smoller JW, et al. Targeted genome screen of panic disorder and anxiety disorder proneness using homology to murine QTL regions. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:195–206. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Squassina A, et al. Evidence for association of an ACCN1 gene variant with response to lithium treatment in Sardinian patients with bipolar disorder. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:1559–1569. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Garriock HA, et al. A genomewide association study of citalopram response in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gregersen N, et al. A genome-wide study of panic disorder suggests the amiloride-sensitive cation channel 1 as a candidate gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:84–90. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stone JL, Merriman B, Cantor RM, Geschwind DH, Nelson SF. High density SNP association study of a major autism linkage region on chromosome 17. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:704–715. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Magnotta VA, et al. Detecting activity-evoked pH changes in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8270–8273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205902109. This study shows that brain activation produces a functional acidosis that is detectable with MRI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Arun T, et al. Targeting ASIC1 in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: evidence of neuroprotection with amiloride. Brain. 2013;136:106–115. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang X, et al. Serotonin facilitates peripheral pain sensitivity in a manner that depends on the nonproton ligand sensing domain of ASIC3 channel. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4265–4279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3376-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wu WL, Lin YW, Min MY, Chen CC. Mice lacking Asic3 show reduced anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze and reduced aggression. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:603–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sherwood TW, Askwith CC. Dynorphin opioid peptides enhance acid-sensing ion channel 1a activity and acidosis-induced neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14371–14380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2186-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dawson RJ, et al. Structure of the Acid-sensing ion channel 1 in complex with the gating modifier Psalmotoxin 1. Nature Commun. 2012;3:936. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Askwith CC, et al. Neuropeptide FF and FMRFamide potentiate acid-evoked currents from sensory neurons and proton-gated DEG/ENaC channels. Neuron. 2000;26:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Staruschenko A, Dorofeeva NA, Bolshakov KV, Stockand JD. Subunit-dependent cadmium and nickel inhibition of acid-sensing ion channels. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:97–107. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang W, Yu Y, Xu TL. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channels by Cu2+ in cultured hypothalamic neurons of the rat. Neuroscience. 2007;145:631–641. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Babinski K, Catarsi S, Biagini G, Seguela P. Mammalian ASIC2a and ASIC3 subunits co-assemble into heteromeric proton- gated channels sensitive to Gd3+ J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28519–28525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang W, Duan B, Xu H, Xu L, Xu TL. Calcium-permeable Acid-sensing ion channel is a molecular target of the neurotoxic metal ion lead. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2497–2505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chu XP, et al. Subunit-dependent high-affinity zinc inhibition of acid-sensing ion channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8678–8689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2844-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Paukert M, Babini E, Pusch M, Grunder S. Identification of the Ca2+ blocking site of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1: implications for channel gating. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:383–394. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sherwood T, et al. Identification of protein domains that control proton and calcium sensitivity of ASIC1a. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27899–27907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.029009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Smith ES, Cadiou H, McNaughton PA. Arachidonic acid potentiates acid-sensing ion channels in rat sensory neurons by a direct action. Neuroscience. 2007;145:686–698. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cadiou H, et al. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channel activity by nitric oxide. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13251–13260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2135-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Birdsong WT, et al. Sensing muscle ischemia: coincident detection of acid and ATP via interplay of two ion channels. Neuron. 2010;68:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chen X, Kalbacher H, Grunder S. The tarantula toxin psalmotoxin 1 inhibits acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a by increasing its apparent H+ affinity. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:71–79. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Diochot S, et al. A new sea anemone peptide, APETx2, inhibits ASIC3, a major acid-sensitive channel in sensory neurons. EMBO J. 2004;23:1516–1525. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Voilley N, de Weille J, Mamet J, Lazdunski M. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit both the activity and the inflammation-induced expression of acid-sensing ion channels in nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8026–8033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08026.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Qadri YJ, Song Y, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Amiloride docking to acid-sensing ion channel-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9627–9635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Adams CM, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. Paradoxical stimulation of a DEG/ENaC channel by amiloride. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15500–15504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dube GR, et al. Electrophysiological and in vivo characterization of A-317567, a novel blocker of acid sensing ion channels. Pain. 2005;117:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ugawa S, et al. Nafamostat mesilate reversibly blocks acid-sensing ion channel currents. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nedergaard M, Kraig RP, Tanabe J, Pulsinelli WA. Dynamics of interstitial and intracellular pH in evolving brain infarct. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R581–R588. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.3.R581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pignataro G, Simon RP, Xiong ZG. Prolonged activation of ASIC1a and the time window for neuroprotection in cerebral ischaemia. Brain. 2007;130:151–158. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Vergo S, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 1 is involved in both axonal injury and demyelination in multiple sclerosis and its animal model. Brain. 2011;134:571–584. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bernardinelli L, et al. Association between the ACCN1 gene and multiple sclerosis in Central East Sardinia. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Jenkins BG, et al. 1H NMR spectroscopy studies of Huntington’s disease: correlations with CAG repeat numbers. Neurology. 1998;50:1357–1365. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tsang TM, et al. Metabolic characterization of the R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease by high-resolution MAS 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:483–492. doi: 10.1021/pr050244o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bowen BC, et al. Proton MR spectroscopy of the brain in 14 patients with Parkinson disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:61–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pidoplichko VI, Dani JA. Acid-sensitive ionic channels in midbrain dopamine neurons are sensitive to ammonium, which may contribute to hyperammonemia damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11376–11380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Joch M, et al. Parkin-mediated monoubiquitination of the PDZ protein PICK1 regulates the activity of acid-sensing ion channels. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3105–3118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yan J, et al. Dural afferents express acid-sensing ion channels: a role for decreased meningeal pH in migraine headache. Pain. 2011;152:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Vila-Carriles WH, Zhou ZH, Bubien JK, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Participation of the chaperone Hsc70 in the trafficking and functional expression of ASIC2 in glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34381–34391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wang RIH, Sonnenschein RR. pH of cerebral cortex during induced convulsions. J Neurophysiol. 1955;18:130–137. doi: 10.1152/jn.1955.18.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lennox WG. The effect on epileptic seizures of varying the composition of the respired air. J Clin Invest. 1929;6:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tolner EA, et al. Five percent CO is a potent, fast-acting inhalation anticonvulsant. Epilepsia. 2011;52:104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]