Abstract

Background: Limited data are available on the accuracy of 24-h dietary recalls used to monitor US sodium and potassium intakes.

Objective: We examined the difference in usual sodium and potassium intakes estimated from 24-h dietary recalls and urine collections.

Design: We used data from a cross-sectional study in 402 participants aged 18–39 y (∼50% African American) in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 2011. We estimated means and percentiles of usual intakes of daily dietary sodium (dNa) and potassium (dK) and 24-h urine excretion of sodium (uNa) and potassium (uK). We examined Spearman's correlations and differences between estimates from dietary and urine measures. Multiple linear regressions were used to evaluate the factors associated with the difference between dietary and urine measures.

Results: Mean differences between diet and urine estimates were higher in men [dNa – uNa (95% CI) = 936.8 (787.1, 1086.5) mg/d and dK – uK = 571.3 (448.3, 694.3) mg/d] than in women [dNa – uNa (95% CI) = 108.3 (11.1, 205.4) mg/d and dK – uK = 163.4 (85.3, 241.5 mg/d)]. Percentile distributions of diet and urine estimates for sodium and potassium differed for men. Spearman's correlations between measures were 0.16 for men and 0.25 for women for sodium and 0.39 for men and 0.29 for women for potassium. Urinary creatinine, total caloric intake, and percentages of nutrient intake from mixed dishes were independently and consistently associated with the differences between diet and urine estimates of sodium and potassium intake. For men, body mass index was also associated. Race was associated with differences in estimates of potassium intake.

Conclusions: Low correlations and differences between dietary and urinary sodium or potassium may be due to measurement error in one or both estimates. Future analyses using these methods to assess sodium and potassium intake in relation to health outcomes may consider stratifying by factors associated with the differences in estimates from these methods. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01631240.

Keywords: biomarker, diet, sodium, urine, validation study

INTRODUCTION

Sodium intake has been consistently associated with blood pressure in a direct, positive relation (1–5) and with cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease (6, 7). Conversely, dietary potassium intake has been inversely associated with cardiovascular disease and risk factors such as high blood pressure and stroke (8–11). National estimates show that >95% of American adults consume more than the recommended amount of sodium and <5% consume the recommended amount of potassium (12, 13). National initiatives and recommendations focused on changing population intakes of sodium and potassium in the United States need an accurate assessment of consumption to monitor the impact of their efforts, to monitor adherence to dietary guidelines, and to determine the association of sodium or potassium with health outcomes.

Current national sodium and potassium intake estimates in US adults are subject to bias. These estimates are obtained from 24-h dietary recalls administered as part of the NHANES. Although day-to-day variability in intake can be accounted for through the use of measurement error models with an additional 24-h dietary recall in a subset of the population, differential misreporting may occur by demographic factors such as sex and BMI (14, 15), which are associated with adherence to sodium or potassium consumption guidelines or their related health disparities.

Although sodium and potassium intake estimates from 24-h urine collections are objective measures (16), as opposed to subjective estimates based on self-reported 24-h dietary recalls, these have not previously been collected in US nationally representative surveys. Although current monitoring relies on 24-h dietary recalls and nutrient databases, it is important to assess the accuracy of dietary intake compared with urinary excretion for sodium and potassium within subgroups with potentially different reporting, intake, and excretion. Some studies investigated the accuracy of nutrient intake estimated from 24-h dietary recalls compared with urine excretion from 24-h urine collections and found correlations ranging from 0.14 to 0.59 for sodium (15, 17–21) and from 0.31 to 0.69 for potassium (22, 23). Most of these studies were conducted in other countries, in persons with chronic diseases, or with limited race-ethnic diversity. Furthermore, only a few studies adjusted for day-to-day variability in intake and compared accuracy by possible effect modifiers, including sex, race-ethnicity, age, or BMI; and no studies considered both sodium and potassium in the same study.

The objectives of the current study were to compare estimates of intakes of dietary sodium (dNa)6 and potassium (dK) based on 24-h diet recalls with urinary excretion of sodium (uNa) and potassium (uK) based on 24-h urine collections between sex, race, age, and BMI subgroups as well as to determine factors associated with the discrepancies between measures by using a study in young adults, in which 50% of the participants were African American. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01631240.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were drawn from a calibration study conducted from June to August 2011 by the National Center for Health Statistics and previously described in detail (24). Briefly, participants were recruited from the Washington, DC, metropolitan area. A convenience sample of 500 young adults (18–39 y old) with diverse sodium intakes (assessed by questionnaire) was recruited such that 50% were African American and 50% were women. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant, taking loop diuretics, reported chronic kidney disease, or were prescribed new or recently modified hypertension treatment.

A total of 481 participants were scheduled for an initial visit, and 402 (84%) participants provided at least one complete 24-h urine sample and a 24-h dietary recall. A complete urine sample was defined as follows: 1) a total 24-h urinary volume >500 mL, 2) no menstruation during the collection period, 3) a reported length of collection >20 h, and 4) missing one void (n = 7) or less during collection. Both urine collection and dietary recall measured the same 24-h period, with the 24-h dietary recall administered on completion of the 24-h urine collection. Of the 402 participants, 219 were women and 196 were African American. A convenience subsample of 133 participants completed a second dietary recall and a 24-h urine collection 4–11 d after the first measure and not on the same day of the week.

Urine and dietary measures

Values for uNa and uK were estimated from the 24-h urine collection by using an ion-selective electrode Na+ and K+ assay (Roche Diagnostics). Estimates of uNa and uK were adjusted for the length of time urine was collected. Further adjustments were made to reflect extrarenal losses of sodium and potassium estimated at 90% (25–27) and 77% (25, 28, 29), respectively, by dividing total daily uNa by 0.90 and uK by 0.77. dNa and dK were obtained from standardized interviewer-administered 24-h dietary recall by using the Automated Multiple-Pass Method (14). Sodium and potassium contents of each food and beverage including water were calculated by using the USDA's Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, version 5.0 (30). Estimates of intake included salt added in cooking and food preparation as assumed in the nutrient profiles for foods. Discretionary salt used at the table was not included.

Other measurements

Body weight and height were measured by using a standard protocol and used to calculate BMI (in kg/m2). BMI was categorized as follows: normal (18.5 to <25), overweight (25 to <30), or obese (≥30). Underweight participants (BMI <18.5; n = 5) were excluded from the analysis considering BMI. Race was self-reported as African American or other.

Statistical methods

Usual dNa, dK, uNa, and uK were calculated by using PC-SIDE (Software for Intake Distribution Estimation; Iowa State University), which implements the Iowa State University method to account for day-to-day variation. This method transforms data into the normal scale and allows adjustment for covariates. As long as a subsample has at least 2 repeated measures, a measurement error model that removes the within-person variation from observed measurements can be fitted (31). The estimated usual intakes are then transformed back into the original scale. Because of different distributions of dNa, dK, uNa, and uK for men and women, measurement error models were fitted separately for each sex and adjusted for day of the week and participant age in years. Analytic exclusion included influential outliers for dNa, dK, uNa, and uK estimates (n = 1). In PC-SIDE, the best linear unbiased predictors of usual dNa, dK, uNa, and uK were calculated for individuals. Study population percentiles with 95% CIs were also calculated (32). Best linear unbiased predictors of usual total caloric intake and urinary creatinine excretion were obtained as well. These estimates of usual quantities were used in all further analyses.

Spearman's correlation between dNa and dK from 24-h dietary recall compared with uNa and uK from 24-h urine collection and the difference (dNa − uNa and dK − uK) were estimated by using STATA 12.0 (StataCorp). Variations in correlations and differences between measures were calculated by sex and then by race (African American or other race), BMI (normal, overweight, and obese), and age group (18–39 y). Bland-Altman plots were used to examine whether the difference between measures varied across the range of consumption by plotting the difference for each individual against the mean of both measures. In Bland-Altman plots, the 95% limits were calculated by the mean difference ± 1.96 × SD. Multiple linear regression was used to evaluate associations between the difference in sodium measures and covariates [race (African American or other races), age (y), and BMI (kg/m2)], urine measures (total 24-h urine volume and urine creatinine), and dietary components [total caloric intake, weekend vs. weekday, and percentage of sodium or potassium from food groups (dairy, protein, mixed dishes, grains, fruit and vegetables, beverages, and other foods)], with adjustment for each of the other covariates. Significance was denoted as a 2-sided P value <0.05.

Sensitivity analysis

All analyses were repeated after excluding participants with potentially incomplete 24-h urine collection based on creatinine concentrations [i.e., a creatinine ratio (observed:expected) <0.6]. Expected creatinine excretion was calculated by using 2 methods: Joossens and Geboers (33) and Mage et al. (34). In the Joossens and Geboers algorithm, expected 24-h creatinine excretion (mg/d) = G × body weight (kg), where G = 21 for women and 24 for men. Mage's algorithms are as follows: for men, expected 24-h creatinine (mg/d) = 0.00179 × [140 – age (y)] × [weight (kg)1.5 × height (cm)0.5] × [1 + 0.18 × (African American = 1, other races = 0)] × [1.366 – 0.0159 BMI (kg/m2)]; for women, expected 24-h creatinine (mg/d) = 0.00163 × [140 – age (y)] × [weight (kg)1.5 × height (cm)0.5] × [1 + 0.18 × (African American = 1, other races = 0)] × [1.429–0.0198 BMI (kg/m2)]. Participants with potentially incomplete 24-h urine collection were defined as having creatinine ratios <0.60 by using one or both methods. Therefore, the sensitivity analysis only included those creatinine ratios ≥0.60 from both methods. In addition, for comparison with results using the usual intake/excretion analyses, results from 1-d measures were calculated and are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

RESULTS

Demographic, dietary, and biomarker measures for the study participants are presented in Table 1. By design, approximately half of the participants were women (54%) or African American (49%). More women (35%) were obese than men (21%). Mean dNa and dK were greater for men (4827 and 3277 mg/d, respectively) than for women (3507 and 2544 mg/d, respectively). Mean dNa was significantly greater than mean uNa in men (4827 vs. 3891 mg/d; P < 0.0001) and women (3507 vs. 3399 mg/d; P = 0.03). Mean dK was significantly greater than mean uK for men and women (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics, dietary nutrient intake, and biomarkers by sex: Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 20111

| Men (n = 183) | Women (n = 219) | P | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.9642 | ||

| African American | 89 (49) | 107 (49) | |

| Other | 94 (51) | 112 (51) | |

| BMI category,3 n (%) | 0.0042 | ||

| Underweight | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| Normal | 77 (42) | 86 (39) | |

| Overweight | 66 (36) | 52 (24) | |

| Obese | 39 (21) | 77 (35) | |

| Age category (y), n (%) | 0.9942 | ||

| 18–22 | 51 (28) | 60 (27) | |

| 23–29 | 72 (39) | 87 (40) | |

| 30–39 | 60 (33) | 72 (33) | |

| Total kilocalories | 2862.5 ± 44.594 | 2157.4 ± 33.00 | <0.0015 |

| Dietary sodium intake, mg/d | 4827.3 ± 73.22 | 3507.3 ± 47.65 | <0.0015 |

| Adjusted urinary sodium excretion,6 mg/d | 3890.6 ± 31.53 | 3399.0 ± 35.84 | <0.0015 |

| Dietary potassium intake, mg/d | 3277.0 ± 58.96 | 2544.0 ± 34.00 | <0.0015 |

| Urinary potassium excretion, mg/d | 2705.7 ± 50.89 | 2380.6 ± 32.84 | <0.0015 |

| Urinary creatinine excretion, mg/d | 1916.6 ± 30.82 | 1342.4 ± 15.08 | <0.0015 |

Usual dietary intakes from the PC-SIDE (Software for Intake Distribution Estimation; Iowa State University) output are presented for total kilocalories, potassium, and sodium intakes. Usual biomarker excretion was estimated from PC-SIDE and included potassium, sodium, and creatinine excretions.

Derived by Pearson's chi-square test for differences in proportions between sex groups.

BMI categories (in kg/m2): underweight (<18), normal (18 to <25), overweight (25 to <30), and obese (≥30).

Mean ± SE (all such values).

Derived by unpaired t test for differences in means between sex groups.

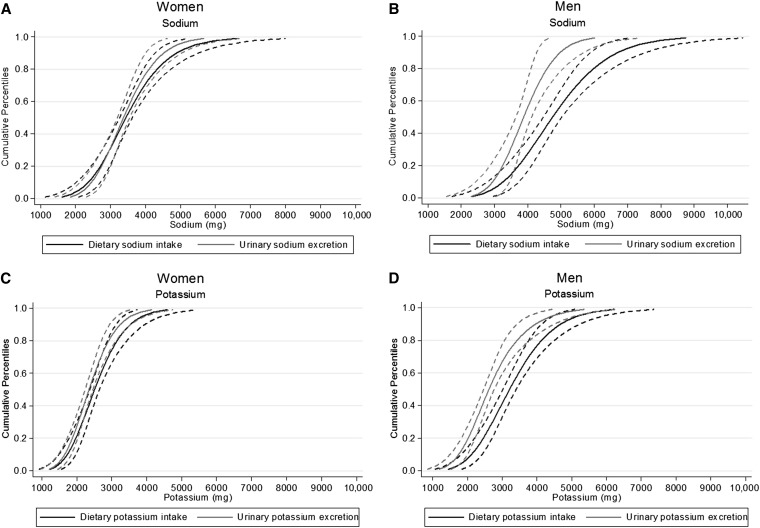

Cumulative population percentiles for dNa and uNa as well as dK and uK are shown for men and women in Figure 1. Distributions for sodium and potassium measures for women were generally similar because CIs were overlapping throughout the entire distributions. For men, dietary distributions were shifted to the right of, or greater than, their respective urine measures, with 95% CIs only overlapping at the tail ends.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative percentiles of dietary intake and urinary excretion for sodium and potassium: Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 2011. Shown are cumulative percentiles (solid lines) with 95% CIs (dashed lines) of dietary intake and urinary excretion for sodium in women (A) and men (B) and for potassium in women (C) and men (D).

Correlation coefficients and the difference between measures (diet minus urine estimates) are shown in Table 2. Correlations between sodium measures were 0.16 (P = 0.03) for men and 0.25 (P < 0.001) for women. Among men, these correlations were highest for those aged 23–29 y (ρ = 0.29) compared with those aged 30–39 y (ρ = 0.03). Among women, the correlations between sodium measures were higher for women of other race-ethnicities (ρ = 0.30) and lowest among African Americans (ρ = 0.15). dNa was, on average, greater than uNa for men, with a mean difference of 936.8 mg/d (95% CI: 787.1, 1086.5 mg/d). This difference did not vary by race (P = 0.93) or age group (23–29 vs. 18–22 y, P = 0.91; 30–39 vs. 18–22 y, P = 0.83) but did appear to vary by BMI category, with significantly smaller mean differences for obese participants compared with participants with a normal BMI (overweight vs. normal, P = 0.18; obese vs. normal, P = 0.002). Compared with men, the mean difference was smaller for women at 108.3 mg/d (11.1, 205.4 mg/d). Within race and age, mean differences for women were minimal, with 95% CIs near or crossing zero. Similar to men, there was some variation in the difference by BMI category in women, with overweight women having a significantly smaller difference than those with normal BMI (overweight vs. normal, P = 0.03; obese vs. normal, P = 0.31).

TABLE 2.

Spearman's correlations (ρ) and differences between dietary intake and adjusted urinary excretion of sodium and potassium by sex: Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 20111

| Sodium |

Potassium |

||||||||||

| n | dNa, mg/d | uNa,2 mg/d | ρ | Difference,3 mg/d | P4 | dK, mg/d | uK, mg/d | ρ | Difference,3 mg/d | P4 | |

| Men | |||||||||||

| All men | 183 | 4827 ± 73.25 | 3891 ± 31.5 | 0.16* | 936.8 (787.1, 1086.5) | — | 3277 ± 59.0 | 2706 ± 50.9 | 0.39** | 571.3 (448.3, 694.3) | — |

| Race | |||||||||||

| African American | 89 | 4815 ± 105.8 | 3871 ± 50.8 | 0.13 | 943.8 (720.4, 1167.1) | Ref | 3273 ± 88.1 | 2503 ± 60.0 | 0.31** | 770.7 (591.8, 949.5) | Ref |

| Other | 94 | 4839 ± 102.0 | 3909 ± 38.3 | 0.20 | 930.2 (725.5, 1134.8) | 0.93 | 3280 ± 79.3 | 2898 ± 76.3 | 0.50** | 382.5 (219.3, 545.7) | 0.002 |

| Age category (y) | |||||||||||

| 18–22 | 51 | 4811 ± 164.9 | 3868 ± 53.9 | 0.13 | 943.3 (610.2, 1276.5) | Ref | 3388 ± 111.7 | 2815 ± 102.1 | 0.39** | 573.3 (320.9, 825.6) | Ref |

| 23–29 | 72 | 4885 ± 104.6 | 3920 ± 51.4 | 0.29* | 965.2 (750.7, 1179.8) | 0.91 | 3174 ± 87.9 | 2651 ± 79.8 | 0.41** | 523.2 (343.9, 702.5) | 0.74 |

| 30–39 | 60 | 4772 ± 122.1 | 3875 ± 58.5 | 0.03 | 897.1 (631.7, 1162.4) | 0.83 | 3306 ± 110.2 | 2678 ± 86.1 | 0.35** | 627.3 (395.7, 858.9) | 0.75 |

| BMI category6 | |||||||||||

| Normal | 77 | 4963 ± 121.6 | 3815 ± 46.3 | 0.18 | 1148.3 (903.6, 1393.0) | Ref | 3389 ± 104.9 | 2672 ± 87.2 | 0.35** | 717.0 (492.4, 941.6) | Ref |

| Overweight | 66 | 4756 ± 125.6 | 3844 ± 45.7 | 0.2 | 912.1 (658.6, 1165.6) | 0.18 | 3201 ± 91.0 | 2689 ± 70.8 | 0.32** | 512.7 (330.6, 694.8) | 0.17 |

| Obese | 39 | 4657 ± 117.9 | 4122 ± 77.6 | 0.17 | 534.7 (279.9, 789.5) | 0.002 | 3183 ± 97.8 | 2823 ± 113.0 | 0.51** | 359.6 (156.8, 562.4) | 0.04 |

| Women | |||||||||||

| All women | 219 | 3507 ± 47.7 | 3399 ± 35.8 | 0.25** | 108.3 (11.1, 205.4) | — | 2544 ± 34.0 | 2381 ± 32.8 | 0.29** | 163.4 (85.3, 241.5) | — |

| Race | |||||||||||

| African American | 107 | 3550 ± 72.2 | 3441 ± 50.3 | 0.15 | 109.1 (−39.1, 257.3) | Ref | 2506 ± 53.3 | 2269 ± 41.9 | 0.10 | 236.9 (111.5, 362.3) | Ref |

| Other | 112 | 3466 ± 62.7 | 3359 ± 50.9 | 0.34** | 107.4 (−21.5, 236.3) | 0.99 | 2581 ± 42.7 | 2487 ± 48.3 | 0.44** | 93.2 (−1.6, 188.0) | 0.07 |

| Age category (y) | |||||||||||

| 18–22 | 60 | 3470 ± 92.3 | 3341 ± 71.4 | 0.30* | 128.7 (−49.3, 306.7) | Ref | 2512 ± 68.1 | 2360 ± 71.8 | 0.37** | 152.7 (7.2, 298.1) | Ref |

| 23–29 | 87 | 3606 ± 68.0 | 3459 ± 57.1 | 0.33** | 146.5 (5.4, 287.5) | 0.88 | 2604 ± 47.6 | 2377 ± 45.1 | 0.36** | 226.9 (122.6, 331.2) | 0.40 |

| 30–39 | 72 | 3420 ± 90.9 | 3375 ± 60.0 | 0.16 | 45.1 (−151.8, 242.0) | 0.54 | 2498 ± 64.5 | 2402 ± 59.3 | 0.17 | 95.6 (−69.2, 260.4) | 0.61 |

| BMI category6 | |||||||||||

| Normal | 86 | 3502 ± 72.1 | 3288 ± 50.9 | 0.18 | 213.7 (59.4, 368.0) | Ref | 2590 ± 55.3 | 2377 ± 53.7 | 0.17 | 213.5 (77.1, 349.8) | Ref |

| Overweight | 52 | 3327 ± 83.6 | 3388 ± 64.1 | 0.28* | −60.7 (−237.4, 116.1) | 0.03 | 2444 ± 73.4 | 2376 ± 64.1 | 0.38** | 67.5 (−87.0, 222.0) | 0.17 |

| Obese | 77 | 3635 ± 91.5 | 3542 ± 69.3 | 0.30** | 93.1 (−87.4, 273.6) | 0.31 | 2561 ± 55.0 | 2405 ± 56.9 | 0.39** | 156.1 (29.6, 282.7) | 0.54 |

Best linear unbiased predictors derived from PC-SIDE (Software for Intake Distribution Estimation; Iowa State University) were used for dNa, uNa, dK, and uK in assessing correlations and differences. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (2-sided P values for Spearman's correlation coefficient). dK, dietary potassium intake; dNa, dietary sodium intake; Ref, reference; uK, urinary potassium excretion; uNa, urinary sodium excretion.

Sodium excretion measures were corrected to account for 90% excretion of all sodium consumed (26, 35).

Difference = dietary intake – urinary excretion.

P values from t test testing if the mean difference between measures was significantly different within categories of race, age, and BMI.

Mean ± SE (all such values).

BMI categories (in kg/m2): normal (18 to <25), overweight (25 to <30), and obese (≥30).

For potassium, correlations between measures were 0.39 (P < 0.0001) for men and 0.29 (P < 0.0001) for women (Table 2). For men, correlation coefficients were highest for those who were obese (ρ = 0.51) and lowest among African Americans (ρ = 0.31). For women, correlations were higher among women of other race-ethnicities (ρ = 0.44) and lowest among African Americans (ρ = 0.10). On average, dK was greater than uK, with mean differences of 571.3 mg/d (95% CI: 448.3, 694.3 mg/d) for men and 163.4 mg/d (95% CI: 85.3, 241.5 mg/d) for women. In men, this difference varied by race (P = 0.002) and BMI (normal vs. overweight, P = 0.17; normal vs. obese, P = 0.04) but did not vary by age group (23–29 vs. 18–22 y, P = 0.74; 30–39 vs. 18–22 y, P = 0.75). However, mean differences within subgroups of race (P = 0.07), age (23–29 vs. 18–22 y, P = 0.40; 30–39 vs. 18–22 y, P = 0.61), or BMI (normal vs. overweight, P = 0.17; normal vs. obese, P = 0.54) were not significant for women.

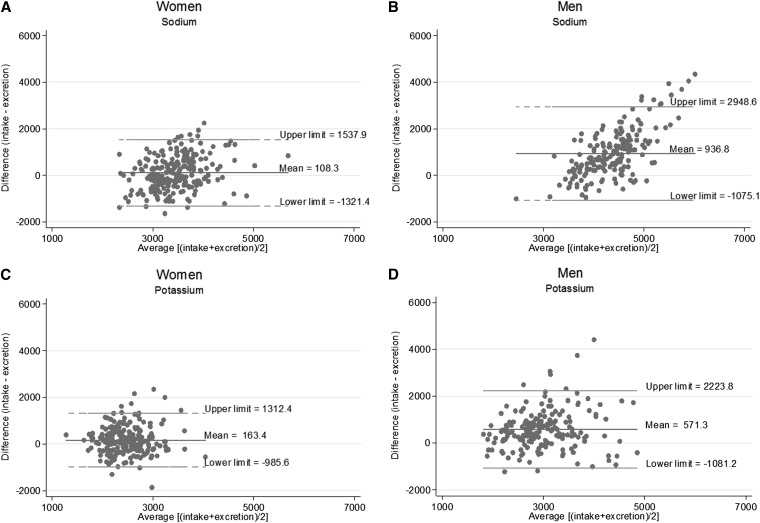

The difference in estimated usual individual sodium intake from diet vs. urine excretion was fairly consistent across amounts of sodium and potassium intakes for women (Figure 2A, C). For men, diet measures generally overestimated sodium intake compared with urine measures, and this overestimation was greater at higher intakes, with several individuals falling outside the upper limit of agreement (2948 mg) at an average intake of ∼4500 mg or more (Figure 2B). For estimated usual potassium intake, individuals also fell outside the limits of agreement, but diet measures appeared to more consistently overestimate urine measures in the middle of the distribution (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Bland-Altman graphs for assessing bias between dietary intake and urinary excretion measures for sodium and potassium: Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 2011. Shown are Bland-Altman graphs with mean differences and 95% limits of agreement (means ± 1.96 SDs) for sodium in women (A) and men (B) and for potassium in women (C) and men (D).

Demographic characteristics (race and age), BMI, urine measures (total 24-h urine volume and urinary creatinine), and dietary components [total caloric intake, weekend vs. weekday, and percentage of sodium or potassium from food groups (dairy, protein, mixed dishes, grains, fruit and vegetables, beverages, and other foods)] associated with the difference between sodium measures (dNa – uNa) are presented in Table 3. BMI in men was significantly associated with the difference in sodium measures, but race and age were not. Of the urine measures, after all of the covariates were controlled for, urine creatinine was significantly associated with the difference in men and women as well as urine potassium in men. Most of the dietary components were significantly associated with the mean difference between sodium measures in men and women.

TABLE 3.

Linear regression coefficients (β) from univariate and multivariate analyses of differences between dietary sodium intake and adjusted urinary sodium excretion according to demographic, diet, and biomarker covariates: Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 20111

| Men (n = 183) |

Women (n = 219) |

|||||

| Difference as a dependent variable2 | β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| Race3 | −13.6 | −314.4, 287.2 | 0.93 | −1.7 | −197.0, 193.6 | 0.99 |

| Age,4 y | −3.8 | −31.8, 24.2 | 0.79 | −1.4 | −18.3, 15.5 | 0.87 |

| BMI,4 kg/m2 | −47.7 | −68.9, −26.5 | <0.001 | −7.2 | −22.5, 8.2 | 0.36 |

| Total 24-h urine volume,5 mL | 0.1 | −0.1, 0.3 | 0.34 | −0.05 | −0.2, 0.1 | 0.57 |

| Urinary potassium, mg/d | −0.1 | −0.3, 0.1 | 0.46 | −0.2 | −0.4, 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Urinary creatinine, mg/d | −0.4 | −0.7, 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.6 | −1.1, −0.2 | 0.007 |

| Total kilocalories | 1.2 | 1.0, 1.5 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of sodium from6 | ||||||

| Dairy | 0.8 | 0.4, 1.1 | <0.001 | 0.6 | 0.2, 0.9 | 0.001 |

| Protein | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.3 | 0.001 |

| Mixed dishes | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Grains | 0.4 | 0.3, 0.5 | <0.001 | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Fruit/vegetables | 0.4 | 0.1, 0.6 | 0.005 | 0.5 | 0.3, 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Beverages | 1.5 | 1.0, 2.0 | <0.001 | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.2 | 0.002 |

| Other foods | 0.6 | 0.2, 1.1 | 0.004 | 0.3 | −0.03, 0.6 | 0.07 |

| Weekend vs. weekday7 | −119.0 | −427.7, 189.7 | 0.45 | −37.2 | −236.6, 162.3 | 0.71 |

| Full model | ||||||

| Race3 | 23.7 | −107.6, 154.9 | 0.72 | 34.8 | −116.4, 186.0 | 0.65 |

| Age,4 y | 7.7 | −2.6, 17.9 | 0.14 | −4.1 | −15.1, 6.9 | 0.47 |

| BMI,4 kg/m2 | −20.9 | −32.6, −9.2 | 0.001 | −8.6 | −19.5, 2.3 | 0.12 |

| Total 24-h urine volume,5 mL | −0.1 | −0.1, 0.02 | 0.17 | −0.1 | −0.3, 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Urinary potassium, mg/d | −0.2 | −0.3, −0.1 | 0.002 | −0.1 | −0.3, 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Urinary creatinine, mg/d | −0.3 | −0.5, −0.1 | 0.008 | −0.7 | −1.0, −0.3 | <0.001 |

| Total kilocalories | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of sodium from6 | ||||||

| Dairy | 0.4 | 0.3, 0.6 | <0.001 | −0.03 | −0.3, 0.3 | 0.85 |

| Protein | 0.3 | 0.3, 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Mixed dishes | 0.4 | 0.3, 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 0.2, 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Grains | 0.4 | 0.4, 0.5 | <0.001 | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Fruit/vegetables | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.5 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.3, 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Beverages | 0.002 | −0.2, 0.2 | 0.98 | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Other foods | 0.5 | 0.3, 0.7 | <0.001 | 0.1 | −0.1, 0.4 | 0.29 |

| Weekend vs. weekday7 | −259.6 | −389.8, −129.5 | <0.001 | −148.5 | −285.3, −11.7 | 0.03 |

Univariate analyses were linear regression models performed for each covariate (independent variable) and the difference (dependent variable). The multivariate model or the full model was one linear regression model with all covariates included. Best linear unbiased predictors derived from PC-SIDE (Software for Intake Distribution Estimation; Iowa State University) were used for dietary sodium intake (dNa) and urinary sodium excretion (uNa) in calculating the difference and for the covariates: urinary potassium, urinary creatinine, and total caloric intake. Sodium excretion measures were corrected to account for 90% excretion of all sodium consumed (26, 35).

Difference between sodium measures = dietary sodium intake – urinary sodium excretion.

The race variable was categorized as African American or other, with African American being the referent group.

Continuous forms of age and BMI were used in the regression models.

Total 24-h urine volume (mL) at the first visit was used in the regression analysis.

Percentage of sodium from each food group (dairy, protein, mixed dishes, grains, fruit/vegetables, beverages, and other foods) was the proportion of total daily sodium from that food group.

Weekend days were Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Weekdays (Monday through Thursday) represented the referent group.

Results from the regression analysis testing the factors associated with the difference between potassium measures (dK – uK) are presented in Table 4. In the full model that adjusted for all covariates, measures significantly associated with the difference in potassium measures were race for both sexes and BMI in men. Similar to the sodium analysis, urine creatinine was significantly associated with the difference between potassium measures for men and women as well as with urine sodium for men. Many of the dietary components were significantly associated with the difference between potassium measures for men and women.

TABLE 4.

Linear regression coefficients (β) from univariate and multivariate analyses of differences between dietary potassium intake and urinary potassium excretion according to demographic, diet, and biomarker covariates: Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 20111

| Men (n = 183) |

Women (n = 219) |

|||||

| Difference as a dependent variable2 | β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| Race3 | −388.1 | −628.6, −147.7 | 0.002 | −143.7 | −300.0, 12.5 | 0.07 |

| Age,4 y | 3.7 | −18.2, 25.5 | 0.74 | −1.1 | −15.8, 13.6 | 0.88 |

| BMI,4 kg/m2 | −19.8 | −41.1, 1.4 | 0.07 | −4.7 | −15.3, 5.9 | 0.39 |

| Total 24-h urine volume,5 mL | −0.1 | −0.3, 0.1 | 0.27 | 0.02 | −0.1, 0.2 | 0.79 |

| Urinary sodium, mg/d | −0.6 | −0.9, −0.3 | <0.001 | −0.1 | −0.2, 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Urinary creatinine, mg/d | −0.4 | −0.8, −0.1 | 0.01 | −0.7 | −1.1, −0.4 | <0.001 |

| Total kilocalories | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.1 | <0.001 | 0.7 | 0.5, 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of potassium from6 | ||||||

| Dairy | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.2 | −0.03, 0.4 | 0.09 |

| Protein | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.7 | 0.002 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Mixed dishes | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 | 0.002 | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.3 | 0.003 |

| Grains | 0.3 | −0.03, 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.4 | −0.01, 0.7 | 0.06 |

| Fruit/vegetables | 0.2 | 0.01, 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.3, 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Beverages | 0.5 | 0.3, 0.7 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.2, 0.8 | 0.001 |

| Other foods | 0.5 | 0.2, 0.8 | 0.002 | 0.2 | −0.3, 0.7 | 0.41 |

| Weekend vs. weekday7 | −19.7 | −280.8, 241.3 | 0.88 | −75.1 | −235.8, 85.5 | 0.36 |

| Full model | ||||||

| Race3 | −337.3 | −501.8, −172.7 | <0.001 | −234.8 | −351.0, −118.5 | <0.001 |

| Age,4 y | −0.6 | −13.7, 12.6 | 0.93 | −7.1 | −15.9, 1.6 | 0.11 |

| BMI,4 kg/m2 | 17.5 | 2.6, 32.5 | 0.02 | 0.3 | −8.4, 9.0 | 0.95 |

| Total 24-h urine volume,5 mL | 0.0 | −0.2, 0.1 | 0.49 | −0.03 | −0.1, 0.1 | 0.61 |

| Urinary sodium, mg/d | −0.4 | −0.6, −0.2 | <0.001 | −0.1 | −0.2, 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Urinary creatinine, mg/d | −0.5 | −0.8, −0.3 | <0.001 | −1.0 | −1.3, −0.7 | <0.001 |

| Total kilocalories | 0.6 | 0.3, 0.8 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.3, 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of potassium from6 | ||||||

| Dairy | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.1 | −0.05, 0.2 | 0.22 |

| Protein | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.5 | <0.001 | 0.2 | −0.04, 0.3 | 0.11 |

| Mixed dishes | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 | 0.003 | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.3 | 0.004 |

| Grains | 0.03 | −0.3, 0.3 | 0.86 | 0.05 | −0.2, 0.3 | 0.66 |

| Fruit/vegetables | 0.1 | −0.02, 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Beverages | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 | 0.002 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.4 | 0.003 |

| Other foods | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 | <0.001 | 0.2 | −0.1, 0.4 | 0.25 |

| Weekend vs. weekday7 | −64.8 | −228.1, 98.5 | 0.43 | −54.3 | −161.0, 52.4 | 0.32 |

Univariate analyses were linear regression models performed for each covariate (independent variable) and the difference (dependent variable). The multivariate model or the full model was one linear regression model with all covariates included. Best linear unbiased predictors derived from PC-SIDE (Software for Intake Distribution Estimation; Iowa State University) were used for dietary potassium intake (dK) and urinary potassium excretion (uK) in calculating the difference and for the covariates: urinary sodium, urinary creatinine, and total caloric intake.

Difference between potassium measures = dietary potassium intake – urinary potassium excretion.

The race variable was categorized as African American or other, with African American being the referent group.

Continuous forms of age and BMI were used in the regression models.

Total 24-h urine volume (mL) at the first visit was used in the regression analysis.

Percentage of potassium from each food group (dairy, protein, mixed dishes, grains, fruit/vegetables, beverages, and other foods) was the proportion of total daily potassium from that food group.

Weekend days were Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Weekdays (Monday through Thursday) represented the referent group.

In the sensitivity analyses with the removal of all participants with potentially incomplete 24-h urine collections based on creatinine concentrations (31 men and 35 women), the results did not substantially change. Also, the results did not differ when removing those who were missing one void (n = 7) in their urine collection.

DISCUSSION

In this study in young adults (18–39 y), dNa and dK from 24-h dietary recalls were significantly greater than uNa and uK from 24-h urine collections. For sodium measures, the difference was small or nonsignificant in most subgroups of women. Sodium differences did not vary by race or age group but did vary by BMI, with greater differences between measures among those with a normal BMI. The differences between potassium measures were smaller than sodium differences for men but not for women. The magnitudes of the correlation coefficients were overall higher between potassium measures than were those for sodium.

Our findings of greater mean dNa and dK than uNa and uK were not anticipated. Although limited studies have compared sodium or potassium estimates from a 24-h dietary recall with 24-h urine collections, most have found mean estimates from urine collection to be greater than those from dietary recall (15, 17, 20, 23, 36–41). We would expect estimates to be greater from a biomarker because these are objective measures that capture nutrients from nondietary sources (water, supplements, and medication), and people are more likely to underreport diet due to recall bias (e.g., misreporting portion size, omitting foods that were consumed or salt added at the table) (42). One study in adults aged 30–69 y (37) using the same dietary method as in this study and another in postmenopausal women aged 50–79 (41) compared dietary estimates with those from 24-h urine collections and found that dNa estimates were <9% lower than uNa estimates. The study in postmenopausal women also considered potassium and found that dK estimates were 12% higher than those of uK (41), a greater overestimation than that observed in the current study (dK estimates were 6% higher than uK among women), possibly due to differences in age and menopausal status of the study populations. The other study corrected for 86% excretion of all sodium consumed and observed greater correlation coefficients between sodium measures (ρ = 0.18–0.59) (37). The use of 86% excretion rather than the 90% in our study would increase the sodium intake estimates from uNa and therefore decrease the difference between measures in men and possibly increase the absolute difference in measures for women. The percentage of sodium and potassium excreted in urine was estimated from studies conducted >20 y ago with small study samples (n < 20) of non-Hispanic whites and did not investigate potential differences in excretion between sex, race, and BMI groups (25, 26, 35). Aside from the adjustment factors used, differences in age, race, and education of participants could explain some of the differences observed between this study and the study by Rhodes et al (36).

We found the difference between sodium and potassium estimates to be greater in men than in women and in those with a normal BMI compared with overweight or obese participants. Possible explanations for these findings include measurement error in dietary or urine collection and physiologic reasons. Dietary measurement error reflects potential inaccuracy of the nutrient database used in this study to capture sodium or potassium contents of foods consumed by the participants and differential misreporting of dietary intake by sex and BMI. Although the nutrient database used was the most up-to-date one available at the time of the study, the percentages of sodium or potassium from most of the 7 food groups considered in this study were significantly associated with the difference between measures. Because the source of each food (grocery store, restaurant, fast food, etc.) is not always considered in estimating the sodium content of each food in the nutrient database and ∼60% of the sodium and 65% of potassium consumed by these participants were from foods purchased at the grocery store, it is possible that many of the foods were prepared at home or contained less sodium than the estimated amount. In addition, differential misreporting of dietary intake has been found by sex and BMI, with women more accurately reporting total dietary intake than men and overweight and obese participants more often underreporting intake compared with those with a normal BMI (14, 36). This may explain why men showed a much greater difference between measures than did women and the directionality of the difference between BMI categories.

It is also possible that the 24-h urine collections were incomplete, because it is very difficult to collect all urine in a 24-h period and we relied on self-report of urine collection completion from participants. When considering total 24-h urine volume and urinary creatinine as proxies for assessing completeness of 24-h urine collections, urinary creatinine was associated with the difference between sodium as well as potassium measures after adjustment for covariates (Tables 3 and 4). It is possible that we observed better agreement between measures in overweight and obese women because they are more likely to underreport diet along with the potential of incomplete urine collections. However, it is important to note that in our sensitivity analysis the results did not change after excluding those with potentially incomplete urine collections based on creatinine concentrations or when excluding those who reported missing any partial or whole voids.

A physiologic possibility that may explain some of the findings is the potential amount of sodium that could have been lost in sweat. Estimates of the amount of sodium excreted in urine and how much could be lost in sweat are variable (43, 44). A study reported that as much as 33–57% of sodium consumed could be lost in sweat, depending on climate and amount of physical activity (45). This study was conducted during the summer months in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area and a greater than anticipated proportion of sodium could have been lost in sweat, possibly explaining why dNa was greater than uNa. In addition, men and those with a normal BMI in this study might have been more physically active because of occupation or lifestyle than women and those who were overweight or obese (46), accounting for the greater difference between sodium measures observed in these subgroups. Furthermore, differences in the excretion of uK between racial groups were previously documented (47–49), yet differential correction factors for the percentage of extrarenal potassium loss have not been estimated, and in this study we used the same correction factor of 77% of potassium consumed is excreted in urine for all participants.

This study is subject to some limitations. First, dietary recall measured the diet for the same 24-h period during which urine was collected. Because the half-life of sodium in the body is ∼24 h (50, 51) and is 16 d for potassium (52), the urinary sodium and potassium collected in this study may not be representative of the dietary sodium measured because measures do not correspond to the same reference period. Furthermore, participants may have changed their eating and drinking patterns during the measurement period because they knew that their diet and urine would be assessed. Our method attempted to address these issues by calculating usual estimates and only using those assessments. However, the correlation coefficients and mean differences between measures were not greatly different when considering only 1-d measures as opposed to the usual sodium estimates (Supplemental Table 1). On average, correlations and mean differences did not differ greatly between the usual estimates and the 1-d values. Another limitation is the number of repeated measures in this study, which was less than that required to accurately estimate individual intakes. Studies show that ≥4 repeated measures are needed to capture individual intake estimates (53). Furthermore, a recent study reported that even at a constant sodium intake, individual day-to-day variability in uNa was large and a 24-h urine collection may not accurately estimate dNa at the individual level (43). Therefore, individual correlations between sodium measures were low due to attenuation that was attributable to measurement error. Also, data on potential confounders for the difference between diet and urine measures, such as physical activity, education attainment, or income, were not collected or considered in this study. In addition, the difference between measures is potentially larger than what was observed in this study due to the unmeasured dietary use of sodium and potassium from supplements or use of salt added at the table. Finally, measurement error from both 24-h dietary recall and urine collection could have influenced the results of this study in other ways.

Strengths of the current study include a racially diverse sample of young adults; the estimation of usual sodium and potassium measures by nutrient distribution estimation software (PC-SIDE), accounting for non-normal distributions and within-person variability in intake; and investigation of factors associated with the difference between sodium and potassium measures through regression modeling. Contrary to previous studies, self-reported sodium and potassium intakes from 24-h dietary recalls were higher than intakes estimated from excretion. Although individual correlations between measures were low, at the population level intake estimates from 24-h dietary recall and urine collection did not differ significantly for women. Although more research is needed to understand differences in measures of sodium and potassium intakes among young adults, future studies should consider stratifying their findings by sex and BMI when assessing sodium consumption as an exposure as well as by race for potassium consumption investigations or include these factors in calibration equations to estimate sodium and potassium intake.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CIM, MEC, ALV, C-YW, CML, AJM, DGR, and ALC: designed the study; MEC, C-YW, and CML: designed the sodium calibration study; C-YW: conducted the sodium calibration study research; AJM and DGR: provided essential nutritional coding for dietary data; ALC: provided statistical guidance for this study; and CIM: analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and has primary responsibility for the final content. All of the authors read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: dK, dietary potassium intake; dNa, dietary sodium intake; uK, urinary potassium excretion; uNa, urinary sodium excretion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Polonia J, Maldonado J, Ramos R, Bertoquini S, Duro M, Almeida C, Ferreira J, Barbosa L, Silva JA, Martins L. Estimation of salt intake by urinary sodium excretion in a Portuguese adult population and its relationship to arterial stiffness. Rev Port Cardiol 2006;25(9):801–17. [PubMed]

- 2.Kwok TC, Chan TY, Woo J. Relationship of urinary sodium/potassium excretion and calcium intake to blood pressure and prevalence of hypertension among older Chinese vegetarians. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwood AM, Sagnella GA, Cook DG, Cappuccio FP. Urinary calcium excretion, sodium intake and blood pressure in a multi-ethnic population: results of the Wandsworth Heart and Stroke Study. J Hum Hypertens 2001;15:229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Ikeda K, Yamori Y. Twenty-four hour urinary sodium and 3-methylhistidine excretion in relation to blood pressure in Chinese: results from the China-Japan cooperative research for the WHO-CARDIAC study. Hypertens Res 2000;23(2):151–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thijssen S, Kitzler TM, Levin NW. Salt: its role in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2008;18(1):18–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Lower levels of sodium intake and reduced cardiovascular risk. Circulation 2014;129:981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013;346:f1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Elia L, Barba G, Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P. Potassium intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1210–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Elia L, Iannotta C, Sabino P, Ippolito R. Potassium-rich diet and risk of stroke: updated meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:585–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Dietary potassium intake and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Stroke 2011;42:2746–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cogswell ME, Zhang Z, Carriquiry AL, Gunn JP, Kuklina EV, Saydah SH, Yang Q, Moshfegh AJ. Sodium and potassium intakes among US adults: NHANES 2003-2008. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:647–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.USDA. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moshfegh AJ, Rhodes DG, Baer DJ, Murayi T, Clemens JC, Rumpler WV, Paul DR, Sebastian RS, Kuczynski KJ, Ingwersen LA, et al. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espeland MA, Kumanyika S, Wilson AC, Reboussin DM, Easter L, Self M, Robertson J, Brown WM, McFarlane M; TONE Cooperative Research Group. Statistical issues in analyzing 24-hour dietary recall and 24-hour urine collection data for sodium and potassium intakes. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:996–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentley B. A review of methods to measure dietary sodium intake. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006;21:63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caggiula AW, Wing RR, Nowalk MP, Milas NC, Lee S, Langford H. The measurement of sodium and potassium intake. Am J Clin Nutr 1985;42:391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlton KE, Steyn K, Levitt NS, Jonathan D, Zulu JV, Nel JH. Development and validation of a short questionnaire to assess sodium intake. Public Health Nutr 2008;11:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang SS, Kang EH, Kim SO, Lee MS, Hong CD, Kim SB. Use of mean spot urine sodium concentrations to estimate daily sodium intake in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nutrition 2012;28:256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiba A, Vald A, Peleg E, Shamiss A, Grossman E. Does dietary recall adequately assess sodium, potassium, and calcium intake in hypertensive patients? Nutrition 2005;21:462–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinivuo H, Valsta LM, Laatikainen T, Tuomilehto J, Pietinen P. Sodium in the Finnish diet: II trends in dietary sodium intake and comparison between intake and 24-h excretion of sodium. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;60:1160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bokhof B, Buyken AE, Dogan C, Karaboga A, Kaiser J, Sonntag A, Kroke A. Validation of protein and potassium intakes assessed from 24 h recalls against levels estimated from 24 h urine samples in children and adolescents of Turkish descent living in Germany: results from the EVET! Study. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crispim SP, de Vries JH, Geelen A, Souverein OW, Hulshof PJ, Lafay L, Rousseau AS, Lillegaard IT, Andersen LF, Huybrechts I, et al. Two non-consecutive 24 h recalls using EPIC-Soft software are sufficiently valid for comparing protein and potassium intake between five European centres—results from the European Food Consumption Validation (EFCOVAL) Study. Br J Nutr 2011;105:447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang CY, Cogswell ME, Loria CM, Chen TC, Pfeiffer CM, Swanson CA, Caldwell KL, Perrine CG, Carriquiry AL, Liu K, et al. Urinary excretion of sodium, potassium, and chloride, but not iodine, varies by timing of collection in a 24-hour calibration study. J Nutr 2013;143(8):1276–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holbrook JT, Patterson KY, Bodner JE, Douglas LW, Veillon C, Kelsay JL, Mertz W, Smith JC., Jr Sodium and potassium intake and balance in adults consuming self-selected diets. Am J Clin Nutr 1984;40:786–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loria CM, Obarzanek E, Ernst ND. Choose and prepare foods with less salt: dietary advice for all Americans. J Nutr 2001;131(Suppl):536S–51S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Mickelsen O, Makdani D, Gill JL, Frank RL. Sodium and potassium intakes and excretions of normal men consuming sodium chloride or a 1:1 mixture of sodium and potassium chlorides. Am J Clin Nutr 1977;30:2033–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark AJ, Mossholder S. Sodium and potassium intake measurements: dietary methodology problems. Am J Clin Nutr 1986;43:470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tasevska N, Runswick SA, Bingham SA. Urinary potassium is as reliable as urinary nitrogen for use as a recovery biomarker in dietary studies of free living individuals. J Nutr 2006;136:1334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahuja JKA, Montville JB, Omolewa-Tomobi G, Heendeniya KY, Martin CL, Steinfeldt LC, Anand J, Adler ME, LaComb RP, Moshfegh AJ. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 5.0. Beltsville (MD): USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carriquiry AL. Estimation of usual intake distributions of nutrients and foods. J Nutr 2003;133(Suppl):601S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carriquiry AL, Camano-Garcia G. Evaluation of dietary intake data using the tolerable upper intake levels. J Nutr 2006;136(Suppl):507S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joossens JV, Geboers J. Monitoring salt intake of the population: methodological considerations In: De Backer GG, Pedoe HT, Ducimetiere P, editors. Surveillance of the dietary habits of the population with regard to cardiovascular diseases, EURONUT report 2. Wageningen (The Netherlands): Department of Human Nutrition, Agricultural University; 1984. p. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mage DT, Allen RH, Kodali A. Creatinine corrections for estimating children's and adult's pesticide intake doses in equilibrium with urinary pesticide and creatinine concentrations. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2008;18:360–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson G, Akesson A, Berglund M, Nermell B, Vahter M. Validation with biological markers for food intake of a dietary assessment method used by Swedish women with three different dietary preferences. Public Health Nutr 1998;1:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhodes DG, Murayi T, Clemens JC, Baer DJ, Sebastian RS, Moshfegh AJ. The USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method accurately assesses population sodium intakes. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:958–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Day N, McKeown N, Wong M, Welch A, Bingham S. Epidemiological assessment of diet: a comparison of a 7-day diary with a food frequency questionnaire using urinary markers of nitrogen, potassium and sodium. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlton KE, Steyn K, Levitt NS, Zulu JV, Jonathan D, Veldman FJ, Nel JH. Ethnic differences in intake and excretion of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium in South Africans. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005;12:355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freisling H, van Bakel MM, Biessy C, May AM, Byrnes G, Norat T, Rinaldi S, Santucci de Magistris M, Grioni S, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, et al. Dietary reporting errors on 24 h recalls and dietary questionnaires are associated with BMI across six European countries as evaluated with recovery biomarkers for protein and potassium intake. Br J Nutr 2012;107:910–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang Y, Van Horn L, Tinker LF, Neuhouser ML, Carbone L, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Thomas F, Prentice RL. Measurement error corrected sodium and potassium intake estimation using 24-hour urinary excretion. Hypertension 2014;63:238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rumpler WV, Kramer M, Rhodes DG, Moshfegh AJ, Paul DR. Identifying sources of reporting error using measured food intake. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:544–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortiz-Melo D, Coffman TM. A trip to inner space: insights into salt balance from cosmonauts. Cell Metab 2013;17:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rakova N, Juttner K, Dahlmann A, Schroder A, Linz P, Kopp C, Rauh M, Goller U, Beck L, Agureev A, et al. Long-term space flight simulation reveals infradian rhythmicity in human Na(+) balance. Cell Metab 2013;17:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Consolazio CF, Matoush LO, Nelson RA, Harding RS, Canham JE. Excretion of sodium, potassium, magnesium and iron in human sweat and the relation of each to balance and requirements. J Nutr 1963;79:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Schoenborn CA, Loustalot F. Trend and prevalence estimates based on the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palacios C, Wigertz K, Martin BR, Braun M, Pratt JH, Peacock M, Weaver CM. Racial differences in potassium homeostasis in response to differences in dietary sodium in girls. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tayo BO, Luke A, McKenzie CA, Kramer H, Cao G, Durazo-Arvizu R, Forrester T, Adeyemo AA, Cooper RS. Patterns of sodium and potassium excretion and blood pressure in the African Diaspora. J Hum Hypertens 2012;26:315–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turban S, Miller ER, III, Ange B, Appel LJ. Racial differences in urinary potassium excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:1396–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strauss MB, Lamdin E, Smith WP, Bleifer DJ. Surfeit and deficit of sodium: a kinetic concept of sodium excretion. AMA Arch Intern Med 1958;102:527–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Epstein M, Hollenberg NK. Age as a determinant of renal sodium conservation in normal man. J Lab Clin Med 1976;87:411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rahola T, Suomela M. On biological half-life of potassium in man. Ann Clin Res 1975;7:62–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.