Abstract

Endometrial and cervical cancer are the most common gynecologic malignancies in the world. Accurate staging of cervical and endometrial cancer is essential for determining the correct treatment approach. The current FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) staging system does not include modern imaging modalities. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has proven to be the most accurate noninvasive imaging modality for staging of endometrial and cervical carcinomas and often assists in patients risk stratification and treatment decisions. Multiparametric MR imaging is increasingly being used in the evaluation of the female pelvis. This approach combines anatomic T2-weighted imaging with functional imaging, i.e. dynamic contrast enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI). In endometrial and cervical cancer MR imaging is used to guide treatment decisions through an assessment of the depth of myometrial invasion and cervical stromal involvement in endometrial cancer, and of tumor size and parametrial invasion in cervical cancer. However, the efficacy of MRI in achieving accurate local staging is dependent on technique and image quality. In this article we discuss optimization of the MR imaging protocol for endometrial and cervical cancer. The use of thin section high resolution (HR) multi-planar T2 weighted images with simple modifications such as double oblique T2 weighted images supplemented by diffusion weighted imaging and contrast enhanced MRI are reviewed.

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma is the fourth most common cancer among women and the most common cancer of the female reproductive tract with an estimated 49,560 new diagnoses and 8,190 deaths in the US in 2013 with average age at the time of diagnosis of 61 years (1). The increasing incidence observed in recent years, is thought to be due to both higher life expectancy and rising rates of obesity. Cervical carcinoma is the third most common gynecologic malignancy with 12,340 new cases and 4,030 deaths in 2013 and average age at the onset 48 years (1). The widespread use of screening with the Papanicolaou smear, and effective treatment of carcinoma in situ have led to a significant decline in cervical cancer in the developed world (2).

The FIGO staging of endometrial cancer is surgical, requiring hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo opherectomy, node dissection, peritoneal washing and omental biopsy for appropriate staging (Table 1) (3) [CME#1]. But distinct from the requirements of FIGO staging is the clinical management of patients with endometrial cancer. Patients that present with an early stage low or intermediate risk disease, which includes stage IA grade 1, 2 and 3, and stage IB grade 1 or 2 endometroid histology can be treated appropriately with minimally invasive laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingoophorectomy. This approach leads to reduced morbidity and hospital stay, and in this group has comparable outcomes to the more extensive surgical resection, which should be reserved for high risk patients with stage IB grade 3 endometrioid, or stage II and above, and all grades non-endometrioid histology, or (4-7). However, the effective implementation of this treatment approach relies heavily on accurate pre-surgical staging. MRI, particularly using the multi-parametric approach has been shown to be reliable in terms of assessment of the key treatment determinants, which are depth of myometrial invasion and cervical stromal involvement (7-11) [CME#2]. Although not part of FIGO, staging MRI is recommended by the National Cancer Institute of France, the European Society of Radiology Guidelines and the Royal College of Radiologists. (12-14).

Table 1. Revised FIGO 2009 Staging System of Endometrial Carcinoma.

| Stage I: | Tumor confined to the corpus uteri |

| IA | No or less than half myometrial invasion |

| IB | Invasion to or more than half of the myometrium |

| Stage II: | Tumor invades cervical stroma, but does not extend beyond the uterus |

| Stage III: | Local and/or regional spread of the tumor |

| IIIA | Tumor invades the serosa and/or adnexae |

| IIIB | Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement |

| IIIC | Metastases to the pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes |

| IIIC1 | Positive pelvic nodes |

| IIIC2 | Positive para-aortic lymph nodes with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes |

| Stage IV: | Tumor invades bladder and/or bowel mucosa, and/or distant metastases |

| IVA | Tumor invasion of bladder and/or bowel mucosa |

| IVB | Distant metastases, including intra-abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes |

FIGO indicates Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians.

“Table reproduced from: Lewin, S.N. (2011) Revised FIGO Staging System for Endometrial Cancer' Clin Obstet Gynecol 54 (2) 215-218”

Assessment of lymph node involvement in endometrial cancer based on size criteria has significant limitations. However, the incidence of nodal involvement correlates with depth of myometrial invasion and cervical stromal involvement, and consequently they can be used as surrogates for determining the need for lymph node dissection (13, 15, 16). Lymph node metastasis increases from 3% when the depth of tumor invasion is less than 50% of the myometrial thickness to 46% with deeper involvement (5, 17, 18).

The role of imaging in endometrial cancer has potentially received a further boost, by the recent modification of the FIGO staging in 2009 (3). The new staging system has combined superficial (<50% thickness of myometrium) invasion and disease confined to the endometrial cavity into one category as stage IA, while tumors invading into the outer half of the myometrium (>50% thickness) are now termed stage IB. In addition the definition of stage II has changed with removal of cervical mucosal involvement as a determinate of upstaging to now only cervical stromal invasion used to define stage II tumors. Distinguishing disease confined to the endometrial cavity from superficial myometrial invasion and defining cervical mucosal involvement, part of prior FIGO staging, was a limitation of imaging. Elimination of these categories could potentially improve the staging accuracy of MR imaging in endometrial cancer (19).

Cervical cancer is the single gynecologic malignancy still staged clinically according to the revised 2009 FIGO classification (Table 2) (20) [CME#3]. However the committee encourages the use of imaging, if available, as clinical staging is inaccurate in 22-75% (21). The use of MR imaging enables a more appropriate triaging of patients to hysterectomy if the tumor is confined to the cervix and < 4 cm in size, or chemo-radiation if tumor size exceeds 4 cm or parametrial invasion is present. Although recent multi-institutional trials have raised concerns about the accuracy of cross-sectional imaging in the staging of early cervical cancer (stage < IIB), MRI still remains the best imaging technique for assessment of tumor size, with a high negative predictive value in excluding parametrial invasion (22-26).

Table 2. New FIGO classification for cervical carcinoma. Figo Committee on Gynecologic Oncology International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 105 (2009) 103-104.

| Stage I: | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus would be disregarded). |

| IA | Invasive carcinoma which can be diagnosed only by microscopy, with deepest invasion ≤5 mm and largest extension ≥7 mm |

| IA1 | Measured stromal invasion of ≤3.0 mm in depth and extension of ≤7.0 mm |

| IA2 | Measured stromal invasion of N3.0 mm and not N5.0 mm with an extension of not N7.0 mm |

| IB | Clinically visible lesions limited to the cervix uteri or pre-clinical cancers greater than stage IA |

| IB1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| IB2 | Clinically visible lesion N4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| Stage II: | Cervical carcinoma invades beyond the uterus, but not to the pelvic wall or to the lower third of the vagina |

| IIA | Without parametrial invasion |

| IIA1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIA2 | Clinically visible lesion N4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIB | With obvious parametrial invasion |

| Stage III: | The tumor extends to the pelvic wall and/or involves lower third of the vagina and/or causes hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney |

| IIIA | Tumor involves lower third of the vagina, with no extension to the pelvic wall |

| IIIB | Extension to the pelvic wall and/or hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney |

| Stage IV: | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved (biopsy proven) the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. A bullous edema, as such, does not permit a case to be allotted to Stage IV. |

| IVA | Spread of the growth to adjacent organs |

| IVB | Spread to distant organs |

“Table reproduced from: Corinne Balleyguier, E. Sale, T. Da Cunha et al. (2011) Staging of uterine cervical cancer with MRI: guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Eur Radiol 21: 1102-1110.”

The realization of these objectives however is dependent on the use of appropriate MRI technique. Recent publications underscore the value of multiparametric MR imaging combining sagittal and oblique axial T2 weighted images (T2WI), DCE and DWI in staging and treatment stratification of patients with gynecologic malignancies (7, 27). In this article we review optimized MR protocols incorporating high resolution T2WIwith an emphasis on the importance of good quality multi-planar images, DCE-MRI) and DWI.

Multiparametric MR Imaging of Endometrial Cancer

The combination of T2 WI and DCE-MRI offers high accuracy in staging endometrial cancer in the range of 83-91% (2, 9, 28, 29), with only a few dissenting papers reporting no added benefit with post contrast images (30, 31). More recent studies have found oblique axial fused T2 and DW images have a high accuracy in assessing depth of myometrial invasion, with some papers reporting not only superior accuracy to DCE-MRI, but also higher inter-observer agreement (32-34).

The incorporation of all three sequences may represent the most comprehensive approach to the preoperative staging of endometrial cancer (7, 27). A significant component of the reliability of the multiparametric approach is the acquisition of good quality multi-planar images, most particularly two planes orthogonal to the tumor obtained, if possible with each sequence, but definitely with the T2 weighted and post contrast T1 weighted sequences. In addition the orthogonal T2WI, DCE-MRI and DW images should co-register by slice location so as to enable correlation of findings on the different sequences. This improves staging accuracy (4).

High Resolution Multiplanar T2-weighted Imaging

TP [T2WI is the key sequence in the evaluation of myometrial invasion, since this sequence provides depiction of the uterine zonal anatomy with the intermediate signal tumor well delineated against the low signal intensity junctional zone] (Fig. 1) (7-9, 11) [CME#4]. However T2WI may be limited in post-menopausal patients, where the zonal anatomy of the uterus is less well defined or if the tumor is isointense to the myometrium.

Figure 1. HR FRFSE T2-weighted images of the uterine zonal anatomy.

Sagittal HR FRFSE T2 image shows the normal zonal anatomy of uterus. The high signal intensity endometrium is surrounded by the homogenous low signal intensity junctional zone (long arrow), which is continuous with the fibrous stroma of the cervix. The myometrium is of intermediate T2 signal (short arrow) and is contiguous with the outer interstitial stroma of the cervix.

Technique

The use of thin section (3 mm) oblique axial and sagittal T2WI (FOV 20-22 cm) is well established in the staging of endometrial cancer (27). Our suggested modification to the imaging protocol is to obtain high resolution T2 weighted fast relaxation fast spin echo (FRFSE) images in three planes, sagittal, coronal and oblique axial. In addition, since the position of uterus is notoriously variable, an oblique axial image based only on the sagittal images occasionally cannot provide an orthogonal view to the tumor. An additional sequence maybe useful, for instances when the uterus is tilted to the left or right of the midline. In such cases, T2 oblique axial images angled off both the sagittal and coronal planes create a “true oblique axial” that is correctly positioned along the true axis of the uterus. This is a “double oblique” sequence as it is oblique in two planes, the sagittal and coronal (Fig. 2). TP [HR double oblique images allow a true orthogonal view of the uterus, with a potential to avoid volume averaging, and improve assessment of myometrial invasion] (Fig 3).

Figure 2. Schematic of the “double oblique” sequence.

The schematic shows uterus that is rotated anteriorly in the sagittal plane (anteverted uterus), but it is also tilted laterally to the left in the coronal plane. The double oblique sequence is obtained by angling images anteriorly in the sagittal plane (green line) and additionally angling images laterally in the coronal plane (blue line), which creates a “true oblique images” along the true axis of the uterus (orange line). A-anterior, P-posterior.

Figure 3. Double oblique MR imaging in endometrial cancer.

(a) HR sagittal FRFSE T2-weighted image illustrates the correct plane for prescribing the orthogonal axial images perpendicular to the endometrial cavity in patients with endometrial carcinoma. The long line (small red arrow) marks the long axis of the uterus and dashed lines indicate the plane of acquisition of the routine oblique axial slices.

(b) HR FRFSE Coronal T2-weighted image shows the body of the uterus is deviated to the right. The second oblique plane is prescribed perpendicular to the axis of the uterus in the coronal plane. The continuous line marks the axis of the endometrial cavity in the coronal plane and the dashed white lines illustrate the acquisition plane of the oblique axial images. The combination of both acquisitions prescribed along the long axis of the uterus in the sagittal and coronal planes form the double oblique axial image.

(c) Routine oblique HR FRFSE T2-weighted image obtained as prescribed only on the sagittal images shows an apparent thinning of the right myometrium (arrow), which potentially could be mistaken for myometrial invasion.

(d) Double oblique HR FRFSE T2-weighted image prescribed using both the sagittal and coronal planes is more appropriately angled along the true axis of the uterus, and shows the thickness of the myometrium to be symmetric (short arrows). Subtle superficial invasion of the inner myometrium is seen along the anterior wall (long arrow). The HR double oblique images are particularly useful when lateral deviation of the uterus is noted in the coronal plane, minimizing problems with volume averaging resulting from uterine position within the pelvis, which may lead to erroneous interpretations of myometrial invasion.

To ensure good spatial resolution and signal to noise ratio (SNR) the images should be acquired using a surface coil appropriately centered over the uterus, using a 20-24 cm field of view (FOV) with 3 mm contiguous cuts. The FOV should be adjusted to ensure appropriate SNR, and if needed, it should be increased as this single step can double the SNR (Fig. 4). It is also valuable to have the patient fast 4-6 hours prior to the scan and empty the bladder before going onto the MR scanner to reduce motion. Antiperistaltic agents, such as hyoscine butylbromide or glucagon, are used in many centers to reduce motion artifacts from bowel peristalsis (27). The phase and frequency direction can also be adjusted to avoid motion artifacts from bowel loops or the bladder wall. A wide anterior saturation fat suppression pulse can generally eliminate motion artifacts from the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Suboptimal images from poor SNR can be improved by increasing FOV.

(a) Coronal HR FRFSE T2-weighted image through the pelvis with 18 cm FOV do not clearly show the endometrial tumor due to poor SNR (arrow).

(b) Coronal HR FRFSE T2-weighted images obtained with a larger FOV (increased from 18 to 20 cm). This simple step doubles the SNR and enables definition of the tumor seen expanding the endometrial cavity (arrow).

Figure 5. Optimizing image quality by eliminating artifacts and improving SNR, with anterior saturation band and adjusting the matrix size.

(a) Oblique axial high resolution T2 weighted images through the uterus are degraded by motion artifact (arrow) and poor SNR, limiting evaluation of the endometrial-myometrial interface (matrix size 320×256).

(b) Placement of an anterior saturation band (long arrow) to eliminate motion artifact from the anterior abdominal wall fat and a decrease in the matrix size (from 320×256 to 256×256) to increase the SNR improves image quality, permitting definition of a polypoid mass (short arrow), confined to the endometrial cavity.

TP [The advantage of using multi-planar high-resolution imaging is a greater confidence in assessment of tumor stage by improved spatial resolution and the ability to confirm the extent of disease in more than one plane which is essential to accurate staging] (Fig. 6) (4, 33) [CME#5].

Figure 6. Value of obtaining two orthogonal planes along the long axis of the tumor.

(a) Sagittal HR FRFSE T2-weighted image shows a polypoid mass expanding the endometrial cavity (short arrow), extending into and expanding the endocervical canal (long arrow). It is difficult to state with certainty if there is myometrial invasion.

(b) Axial HR FRFSE T2- weighted image along the coronal plane of the uterus, and orthogonal to the sagittal T2 images shows a broad based myometrial invasion along the right lateral wall (arrow), which is limited to the inner half of the myometrium. The depth of myometrial invasion was assessed using the thickness of the contralateral wall as a basis for assessment (double headed arrow). This was confirmed by pathology.

Although T2 weighted images are essential, they often prove inadequate due to poor tumor-myometrium contrast, poor definition of the junctional zone particularly in postmenopausal patients, adenomyosis and leiomyomas that compromise accurate staging (Fig. 7). DCE-MRI and DWI can occasionally help to overcome these potential pitfalls. The relative merits of T2WIand DCE-MRI appear to be related the menopausal status, with T2-weighted scans showing a greater accuracy in staging in premenopausal patients and DCE-MRI in postmenopausal patients (35).

Figure 7. Adenomyosis can confound the assessment of myometrial invasion.

(a) Sagittal HR FRFSE T2- weighted image shows widening of the junctional zone and small punctate foci of T2 hyperintensity and striations in the anterior myometrium reflecting adenomyosis (short arrow). The tumor is seen in the endometrial cavity (long arrow).

(b) The sagittal 3D T1 post contrast images show defects in the anterior myometrium corresponding to the finding on the sagittal T2- weighted images (arrow). In this instance the signal intensity on the T2 weighted image and sharply marginated appearance on the post contrast image suggest adenomyosis in the anterior inner myometrium rather than tumor infiltration, but tumor infiltration cannot be excluded with certainty. The presence of adenomyosis limits the ability to accurately assess myometrial invasion on either sequence.

Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MR Imaging

With the exception of a few dissenting reports it has been widely accepted that the use of DCE-MRI improves accuracy of tumor staging in endometrial cancer. This is essentially a consequence of the improved tumor-myometrial contrast generally seen on the delayed 2-4 minute scans, where most endometrial tumors appear hypointense against the enhancing myometrium (Fig. 8). There are additional benefits of the post contrast scans, small tumors that may be difficult to define on the T2WI may appear hypervascular on the early arterial phase images and in patients with loss of the junctional zone or adenomyosis. These post contrast images can assist in assessment of depth of myometrial invasion, while the definition of the intact enhancing cervical mucosa excludes cervical stromal invasion (27, 33). A limitation encountered with DCE-MRI images is that some tumors may be isointense relative to the myometrium on the equilibrium phase (2 min post injection), negating the benefit of this sequence.

Figure 8. Value of Post Contrast T1 weighted images in Assessment of Myometrial Invasion.

(a) Sagittal HR FRFSE T2-weighted image shows a small endometrial mass in the fundus of the uterus (arrow).

(b) Sagittal dynamic 3D T1 FSPGR image shows myometrial invasion along the posterior uterine wall (arrow) confined to the inner myometrium. The delayed post contrast image (2-4 min) optimizes contrast between the myometrium and tumor.

Technique

The efficacy of DCE-MRI in staging relies on obtaining images in two orthogonal planes (33). This is achieved by acquisition of images in the sagittal and oblique axial plane. Most commonly dynamic fat suppressed 3D T1 fast spoiled gradient echo images (3D FSPGR) are acquired in the sagittal plane. These may be obtained at 30, 60, 120 seconds or by scanning continuously through the uterus for 2 minutes. This is followed by delayed (3-4 min) oblique axial fat suppressed 3D T1 weighted images along the axis of the uterus preferably with the same slice positioning as the oblique axial T2 weighted images (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Coregistration of HR FRFSE T2 and DCE-MRI utilizing same slice position.

(a) High resolution axial T2 weighted images through the uterus show a hyperintense tumor in the endometrial cavity with a subtle area of signal abnormality seen in the anterior myometrium, suggesting possible invasion (short arrow). The images are degraded by motion artifact, which limits evaluation (long arrow). Note that an anterior saturation pulse was not placed over the anterior abdominal wall fat.

(b) The delayed post contrast 3D T1 weighted images in the same plane confirm invasion into the inner myometrium (arrow). These images show the value of postcontrast images obtained in the same plane as the T2 weighted images in confirming a subtle finding, and providing a backup if one series is degraded by artifact and suboptimal for diagnostic evaluation.

Diffusion Weighted Imaging

DWI is a functional imaging technique whose contrast derives from the differences in restriction of motion of water molecules. The clinical utilization of DWI in gynecologic malignancies has been steadily increasing over the recent years (36-39). Studies have shown a significantly lower ADC value for endometrial cancer (0.86-0.98 × 10×-3/mm2/s) then normal endometrium (1.28-1.65 × 10×-3/mm2/s) and higher grade endometrial cancers exhibit a tendency toward lower ADC values than more well differentiated tumors (36, 37, 40, 41). These distinct ADC values of endometrial malignancies can help in localizing the tumor in the midst of the normal endometrium, and this facilitates tumor staging.

Recent reports evaluating the efficacy DWI in staging concluded that DWI with relatively high b value (1000 sec/mm2) fused with T2WI provided accurate assessment of myometrial invasion, which reportedly improves the accuracy of T2WI and DCE-MRI (32). The impact of this technique was particularly evident with tumors that are iso-intense to the myometrium on DCE-MR images or where intravenous contrast cannot be utilized.

Technique

DW images should be obtained with variable b values in the range of 50 and 500-1000 preferred in the pelvis. The images should ideally be acquired in the same plane and with a comparable FOV as the oblique axial T2 weighted and DCE images and then fused. If the images cannot be fused, the slice locations should be co-registered on all three sequences to permit correlation (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Value of DW imaging obtained in comparable planes as the HR T2 FRFSE.

(a) A HR FRFSE T2 weighted axial image that is coronal to the plane of the uterus because of angulation of uterus shows a tumor expanding the endometrial cavity with possible invasion of the right myometrium (arrow).

(b) The oblique axial HR FRFSE T2 weighted images did not adequately delineate depth of invasion (arrow).

(c and d) The DWI and ADC map image obtained with comparable obliquity shows restricted diffusion throughout the entire endometrium and confirms tumor infiltration into the right myometrium (short arrow). This case illustrates the value of obtaining DW imaging in an identical imaging plane to the FRFSE T2 images to increase confidence in assessment of depth of myometrial invasion. The endometrial cavity (long arrow) shows low ADC value compatible with tumor. Pathology confirmed tumor occupying the entire endometrial cavity and superficial invasion of the right myometrium.

During interpretation, it is important that DW images always be read in conjunction with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps to avoid misinterpretation related to T2 shine through.

MR Imaging of Cervical Cancer

The utility of the multiparametric approach is limited in cervical cancer and multiplanar T2-weighted imaging remains the mainstay of staging. The reported accuracy of T2WI for evaluation of the cervical tumor diameter is 83% to 93% and from 80% to 87% for assessment of parametrial extension (20, 25, 42, 43) [CME#6]. Although this accuracy has not been reproduced in multi-institutional trials, MRI still remains best imaging modality for tumor visualization and assessment of tumor size, which is an important prognostic factor and determinant of treatment (Fig. 11). In addition, it has a very high negative predictive value in excluding parametrial invasion, confirming its value in identifying patients who may be candidates for surgery (22, 23) [CME#7]. HR MR images in multiple planes provide excellent assessment of the relationship of the cervical tumor to the bladder, rectosigmoid, and pelvic sidewall; influencing staging and chemoradiation planning (Fig. 12) [CME#8].

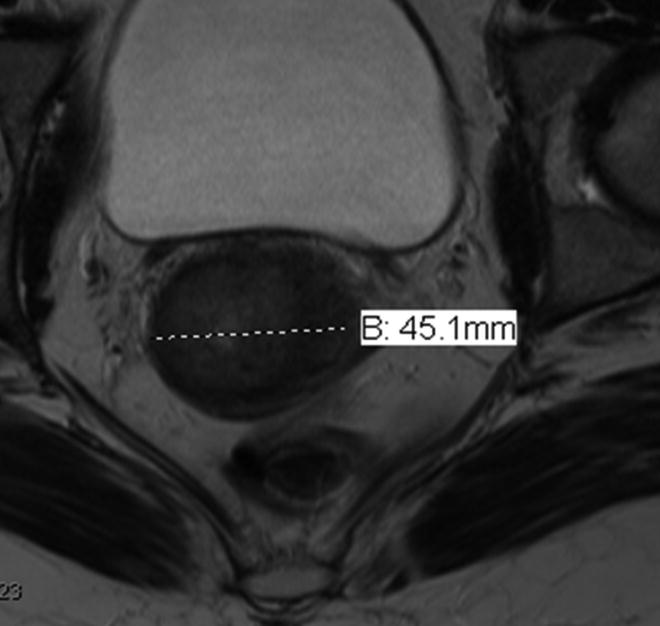

Figure 11. Value of multiplanar HR MRI in adequate assessment of the tumor size.

The measurements of the cervical tumor size should be obtained in all three orthogonal planes in order to achieve accurate size measurement. (a) Axial HR T2-weighted image size measurement of 4.5 cm underestimates tumor size in this patient with large cervical tumor. (b) Sagittal HR T2- weighted image demonstrates actual extent of the disease with largest measurement 6.1 cm.

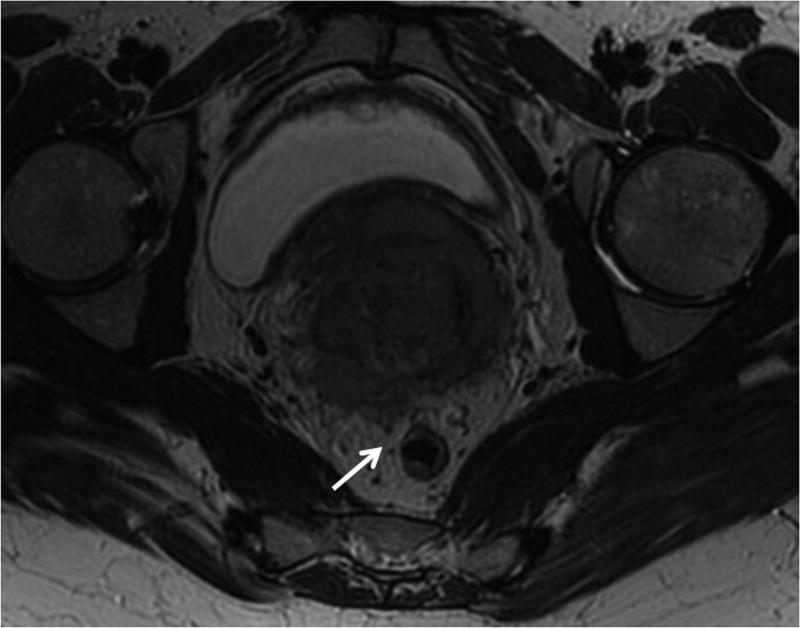

Figure 12. HR MRI of locally advanced cervical cancer with bladder involvement (stage IVA).

(a) Sagittal HR FRFSE T2-weighted image shows a large mass replacing the entire cervix and invading the body of the uterus. Note extension of tumor into the bladder mucosa (short vertical arrow) and perirectal fat (long oblique arrow).

(b) HR oblique FRFSE T2-weighted image shows irregular protrusions of tumor circumferentially infiltrating the parametria, consistent with bilateral parametrial extension, more prominent on the left (long horizontal arrow). Note invasion of the posterior wall of the urinary bladder with mucosal involvement on the left (short vertical arrow).

High resolution T2WI in the oblique axial and sagittal plane are widely accepted as essential for imaging cervical cancer (27). Previous studies have shown that 3 mm thick oblique axial T2 weighted images even if obtained with the body coil improve assessment of parametrial invasion over routine axial T2 weighted images (44). In our experience, the addition of coronal and double oblique high resolution T2WImay provide added benefits in specific circumstances.

High Resolution Multiplanar T2 weighted MR imaging

HR T2 weighted images in the sagittal, and oblique axial planes are the key sequences (Fig. 13). However in situations where the cervix is angled to the left or right as defined in the coronal plane, the routine oblique axial T2 weighted image may be limited by volume averaging. In this situation a double oblique T2 weighted angled based on the sagittal and coronal T2 images is particularly useful as it enables acquisition of images along the axis of the cervix and clear definition of the intact “donut” of the cervical stromal ring (Fig. 14) [CME#9].

Figure 13. The value of orthogonal multiplanar HR FRFSE T2- weighted sequences for evaluation of cervical cancer.

(a) High grade cervical adenocarcinoma seen as a hyperintense mass on the sagittal T2-weighted images (arrow).

(b) The axial T2-weighted image is coronal to the plane of the tumor, limiting the evaluation for cervical stroma and parametrial invasion. The fibrous stroma on the right has an irregular contour (long arrow) and there are minute interruptions of the fibrous stroma on the left, suggesting deep cervical stromal invasion and possible parametrial extension (short arrows).

(c) The oblique axial high resolution T2- weighted image perpendicular to the axis of the cervix, obtained at the level of possible deep cervical stromal invasion and parametrial extension, showed an intact thin layer of preserved fibrous stroma bilaterally (arrows), indicating the tumor is confined to the cervix.

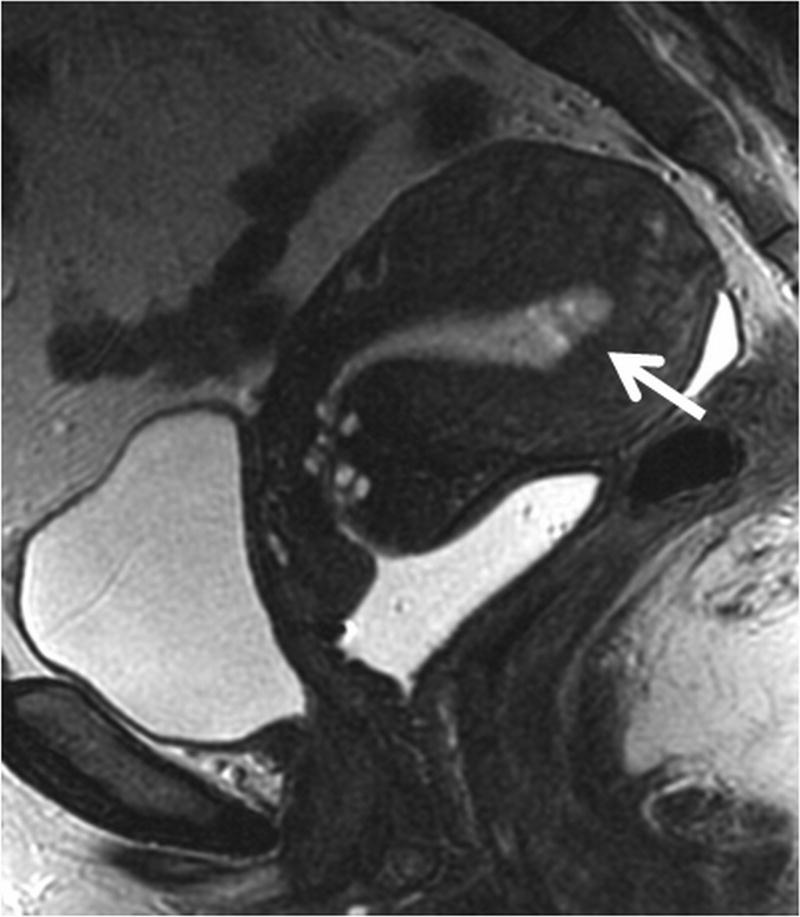

Figure 14. Value of double-oblique HR FRFSE T2-weighted images for parametrial invasion evaluation in cervical cancer.

(a) Sagittal HR FRFSE T2-weighted image shows an intermediate T2 signal intensity mass in the posterior cervical lip (arrow). The dashed line illustrates the acquisition plane of the oblique axial images obtained perpendicular to the long axis of the cervix, indicated by the continuous line.

(b) Axial HR FRSE oblique T2-weighted image obtained based on the sagittal T2-weighted images shows the mass in the posterior cervical lip with suggestion of tumor infiltration into the left parametrium (arrow).

(c) The cervix however is seen to be angled to the left of the mid line on the coronal T2 weighted images (arrow). The dashed line illustrates the angle of acquisition of the double oblique axial image perpendicular to the long axis of the laterally deviated cervix, which is indicated by the continuous line.

(d) A double oblique T2- weighted image angled along the axis of the cervix based on the both the sagittal and coronal images shows an intact cervical stroma (arrow) between the tumor and the parametrium, excluding parametrial invasion on the left. This illustrates the value of double oblique images in eliminating the effects of volume averaging.

Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI

DCE-MRI has no value in assessment of parametrial invasion, but some reports have suggested its value in identifying small cervical tumors particularly if fertility sparing procedures are being considered and also in advanced disease in defining involvement of the bladder wall (45).

Diffusion Weighted Imaging

DW imaging currently has little value in the staging of cervical cancer, but has been used in the localization of small cervical tumors, in conjunction with T2 weighted images. There are a few reports showing cervical cancer ADC value (0.757 – 1.11 × 10x-3/mm2/s) to be significantly lower than that of a normal cervix (1.33 – 2.09 × 10x-3/mm2/s), which could potentially play a role in diagnosis and/or staging (36, 46, 47).

3D T2 Imaging

The above described T2 weighted sequences may be supplemented with 3D T2 fast spin echo images. TP [This technique consistently provides images with high SNR and contrast to noise ratio (CNR), excellent T2 contrast and superior anatomic definition, in addition to the ability to retrospectively generate multi-planar images] (Fig. 15).

Figure 15. The value of 3DT2 sequence in cervical cancer imaging.

(a) HR oblique FRFSE T2-weighted image shows a locally advanced cervical mass with bilateral parametrial extension (long arrows). The tumor invades the posterior cul-de-sac and abuts the anterior rectal wall (short arrow).

(b) HR 3D T2-weighted image enables subsequent post-processing and image manipulation with alteration in the angle of the oblique axial image to show a clear fat plane between tumor and anterior rectal wall (arrow), which is an important factor for planning of the radiation therapy. The excellent T2 contrast of this sequence in addition to its multiplanar reformation capability makes it a valuable asset for evaluation of patients in equivocal cases.

(c) The 3D T2-weighted images can be reviewed on any desirable imaging plane on a dedicated workstation. The multiplanar reformation capability of this sequence in addition to its excellent T2 contrast is very useful when additional anatomic detail is needed for the correct diagnosis and treatment planning.

Technique

Images are acquired with 2 mm thickness and should be preferably in the same plane as the oblique axial T2 FRFSE images. Occasionally, this technique is limited by the inability to apply the no phase wrap function, and consequently a larger FOV needs to be acquired to prevent aliasing. This limits the resolution of the acquired images.

Use of Vaginal Gel

There is no consensus in the literature regarding use of vaginal contrast (2, 9, 20, 28, 48). Therefore, the use of vaginal contrast remains optional. Vaginal gel is useful for the evaluation of cervical cancer patients, especially in the subgroup who do not undergo evaluation under anesthesia. About 20-30 ml of warm ultrasound gel is placed in the vagina after positioning the patient on the table. Usually, vaginal contrast is well tolerated and does not cause any significant discomfort. Vaginal opacification with gel provides high signal intensity on T2W images and enables excellent definition of vaginal fornices and cervix, allowing for accurate assessment of vaginal involvement, especially in tumors with an exophytic cervical component (Fig. 16) [CME#10].

Figure 16. HR MR Imaging with endovaginal gel.

HR sagittal FRFSE T2-weighted sequence shows a large mass replacing the anterior and posterior cervical lips and protruding into the upper third of the vagina. The presence of high T2 signal endovaginal gel distends the vaginal fornices (arrows) and separates them from intravaginal exophytic component of the tumor. The vaginal wall and forniceal insertions are separate from the tumor, and there is preservation of the normal low T2 signal intensity of the muscular vaginal wall, excluding vaginal invasion.

MR Imaging of Lymph Node Involvement

Metastasis to the regional lymph nodes is one of the most important prognostic factors in endometrial cancer and included in the FIGO surgical staging of endometrial cancer. The presence of nodes upstages endometrial cancer to a stage IIIC1 or IIIC2, depending on whether pelvic or para-aortic nodes are involved (3). The FIGO staging of cervical cancer is clinical and does not include adenopathy. However, nodal involvement has significant prognostic implications and is very important in treatment planning (20, 28, 49).

Assessment of nodal involvement in using cross sectional imaging techniques continues to rely on nodal size, which has significant limitations, with sensitivity in the range of 38-89% and specificity from 78-99% (20, 49-53).

TP [The incorporation of morphologic features of nodal involvement best seen on high resolution T2 WI, including internal heterogeneity, spiculated nodal margins, necrosis, signal intensity comparable to the primary tumor, has improved accuracy of nodal involvement evaluation in rectal cancer and is potentially applicable to endometrial and cervical cancer] (54).

Technique

The high resolution coronal T2WI provide the best assessment of pelvic nodes that may be involved in cervical and endometrial cancer i.e. parametrial, obturator, internal, external iliac, and common iliac nodal stations (Fig. 17).

Figure 17. HR MR imaging of metastatic lymphadenopathy.

Coronal HR FRFSE T2-weighted image shows a large cervical mass with bilateral parametrial extension (short horizontal arrows). Bilateral external iliac lymphadenopathy is identified (long vertical arrows). The nodes display an abnormal signal intensity that matches the signal intensity of the primary cervical tumor. HR MR imaging is useful to demonstrate abnormal alterations in nodal morphology and signal intensity, even in normal sized lymph nodes, increasing the sensitivity for nodal disease detection.

Large FOV axial T2 fast spin echo series from the top of the kidneys through L3 (FOV 30-38 cm, slice thickness 5 mm) allows assessment of para-aortic lymphadenopathy as well as presence of hydronephrosis. The main as well as optional MRI sequences discussed in this article are presented in the Table 3. More precise tailoring of the MRI protocol should be done on the basis of the type of gynecologic malignancy with optional sequences used as needed to improve cancer staging (7, 27).

Table 3. High Resolution GYN MRI Pelvis Protocol.

| Main Sequences | Optional Sequences | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERIES | 1 Sagittal T2 | 2 Coronal T2 | 3 Axial T2 | 4 Oblique Axial T2 | 5 Axial T2 Upper Body | 6 Oblique Axial DWI | 7 Double Oblique Axial T2 | 8 Sagittal FS 3D DCE | 9 Oblique Axial Postcontrast FS 3D | 10 Axial 3D T2 |

| PULSE SEQ | FRFSE | FRFSE | FSE | FRFSE | FSE | DWI-EPI | FRFSE | FSPGR | FSPGR | 3DFSE |

| TE (ms) | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 75 | 102 | 2 | 2 | variable |

| TR (ms) | >3000 | >3000 | >3000 | 4500 | 3000-5000 | 1200 | 4500 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 2000 |

| FOV (cm) | 20-24 | 18 -22 | 28 -34 | 18 | 28- 34 | 30-38 | 18 | 22 | 22 - 28 | 22-28 |

| THK (mm) | 3-4 | 3-4 | 5 | 3-4 | 5 | 4-5 | 3-4 | 3-4 | 3-4 | 2 |

| TIME | 4:08 | 6:00 | 5:30 | 6:25 | 4.25 | 2:30 | 6:25 | 3:21 | 2:00 | 7.00 |

| Comments | Pelvic Survey | Retroperitoneum Survey | Match plane to oblique axial T2 images | Used if uterus or cervix are off midline | Cover uterus 25, 60, 120 sec or scan continuously 2 min. Used for Endometrial Ca | 3 - 4 min delay. Used for Endometrial Ca | ||||

Note: FSE - fast spin echo, FRFSE - fast recovery FSE, FS - fat saturation, 3D - three-dimensional, DCE - dynamic contrast enhanced, DWI - diffusion weighted imaging, EPI - echo-planar imaging, FSPGR - fast spoiled gradient echo.

Conclusion

Optimization of the MR imaging protocol with use of thin section high resolution multi-planar T2 weighted images, addition of simple modifications such as double oblique T2 weighted images, supplemented by diffusion weighted imaging and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI improves staging and treatment planning of the endometrial and cervical cancer.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR), 1975–2010. [Accessed April 8, 2013];National Cancer Institute [serial online] 2012 Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/

- 2.Sala E, Wakely S, Senior E, Lomas D. MRI of malignant neoplasms of the uterine corpus and cervix. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):1577–1587. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewin SN. Revised FIGO staging system for endometrial cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(2):215–218. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182185baa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sala E, Rockall A, Kubik-Huch RA. Advances in magnetic resonance imaging of endometrial cancer. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(3):468–473. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-2010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson DM, Connor GP, Broste SK, Krawisz BR, Johnson KK. Prognostic significance of gross myometrial invasion with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(3):394–398. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi M, Watari H, Takeda M, Sakuragi N. Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9721):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman SJ, Aly AM, Kataoka MY, Addley HC, Reinhold C, Sala E. The revised FIGO staging system for uterine malignancies: implications for MR imaging. Radiographics. 2012;32(6):1805–1827. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frei KA, Kinkel K. Staging endometrial cancer: role of magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13(6):850–855. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manfredi R, Gui B, Maresca G, Fanfani F, Bonomo L. Endometrial cancer: magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30(5):626–636. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanjuan A, Escaramis G, Ayuso JR, et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging and cause of pitfalls in detecting myometrial invasion and cervical involvement in endometrial cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(6):535–539. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0636-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cade TJ, Quinn MA, McNally OM, Neesham D, Pyman J, Dobrotwir A. Predictive value of magnetic resonance imaging in assessing myometrial invasion in endometrial cancer: is radiological staging sufficient for planning conservative treatment? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(7):1166–1169. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181e9509f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Querleu D, Planchamp F, Narducci F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial cancer in France: recommendations of the Institut National du Cancer and the Societe Francaise d'Oncologie Gynecologique. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(5):945–950. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bd473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinkel K, Forstner R, Danza FM, et al. Staging of endometrial cancer with MRI: guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Imaging. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(7):1565–1574. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husband JE, Padhani AR, Radiologists RCo. Recommendations for Cross-Sectional Imaging in Cancer Management: Royal College of Radiologists. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frei KA, Kinkel K, Bonel HM, Lu Y, Zaloudek C, Hricak H. Prediction of deep myometrial invasion in patients with endometrial cancer: clinical utility of contrast-enhanced MR imaging-a meta-analysis and Bayesian analysis. Radiology. 2000;216(2):444–449. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00au17444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707–1716. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman ML, Ballon SC, Lagasse LD, Watring WG. Prognosis and treatment of endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;136(5):679–688. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creasman WT, Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Homesley HD, Graham JE, Heller PB. Surgical pathologic spread patterns of endometrial cancer. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 1987;60(8 Suppl):2035–2041. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901015)60:8+<2035::aid-cncr2820601515>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beddy P, O'Neill AC, Yamamoto AK, Addley HC, Reinhold C, Sala E. FIGO staging system for endometrial cancer: added benefits of MR imaging. Radiographics. 2012;32(1):241–254. doi: 10.1148/rg.321115045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balleyguier C, Sala E, Da Cunha T, et al. Staging of uterine cervical cancer with MRI: guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(5):1102–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1998-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Nagell JR, Jr, Roddick JW, Jr, Lowin DM. The staging of cervical cancer: inevitable discrepancies between clinical staging and pathologic findinges. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(7):973–978. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(71)90551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hricak H, Gatsonis C, Chi DS, et al. Role of imaging in pretreatment evaluation of early invasive cervical cancer: results of the intergroup study American College of Radiology Imaging Network 6651-Gynecologic Oncology Group 183. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9329–9337. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hricak H, Gatsonis C, Coakley FV, et al. Early invasive cervical cancer: CT and MR imaging in preoperative evaluation - ACRIN/GOG comparative study of diagnostic performance and interobserver variability. Radiology. 2007;245(2):491–498. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2452061983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenstedt K, Hellstrom AC, Fridsten S, Blomqvist L. Impact of MRI in the management and staging of cancer of the uterine cervix. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(3):420–426. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.541932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamimori T, Sakamoto K, Fujiwara K, et al. Parametrial involvement in FIGO stage IB1 cervical carcinoma diagnostic impact of tumor diameter in preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(2):349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrandina G, Petrillo M, Restaino G, et al. Can radicality of surgery be safely modulated on the basis of MRI and PET/CT imaging in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered preoperative treatment? Cancer. 2012;118(2):392–403. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sala E, Rockall AG, Freeman SJ, Mitchell DG, Reinhold C. The added role of MR imaging in treatment stratification of patients with gynecologic malignancies: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiology. 2013;266(3):717–740. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhosale P, Peungjesada S, Devine C, Balachandran A, Iyer R. Role of magnetic resonance imaging as an adjunct to clinical staging in cervical carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34(6):855–864. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181ed3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sala E, Crawford R, Senior E, et al. Added value of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in predicting advanced stage disease in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(1):141–146. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181995fd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung HH, Kang SB, Cho JY, et al. Accuracy of MR imaging for the prediction of myometrial invasion of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104(3):654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockall AG, Meroni R, Sohaib SA, et al. Evaluation of endometrial carcinoma on magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(1):188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin G, Ng KK, Chang CJ, et al. Myometrial invasion in endometrial cancer: diagnostic accuracy of diffusion-weighted 3.0-T MR imaging--initial experience. Radiology. 2009;250(3):784–792. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503080874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sala E, Rockall A, Rangarajan D, Kubik-Huch RA. The role of dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the female pelvis. Eur J Radiol. 2010;76(3):367–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beddy P, Moyle P, Kataoka M, et al. Evaluation of depth of myometrial invasion and overall staging in endometrial cancer: comparison of diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2012;262(2):530–537. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee EJ, Byun JY, Kim BS, Koong SE, Shinn KS. Staging of early endometrial carcinoma: assessment with T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR imaging. Radiographics. 1999;19(4):937–945. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.4.g99jl06937. discussion 946-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy A, Medjhoul A, Caramella C, et al. Interest of diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient mapping in gynecological malignancies: a review. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(5):1020–1027. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Punwani S. Diffusion weighted imaging of female pelvic cancers: concepts and clinical applications. Eur J Radiol. 2011;78(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whittaker CS, Coady A, Culver L, Rustin G, Padwick M, Padhani AR. Diffusion-weighted mr imaging of female pelvic tumors: A pictorial review1. Radiographics. 2009;29(3):759–774. doi: 10.1148/rg.293085130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Namimoto T, Awai K, Nakaura T, Yanaga Y, Hirai T, Yamashita Y. Role of diffusion-weighted imaging in the diagnosis of gynecological diseases. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(3):745–760. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujii S, Matsusue E, Kigawa J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the apparent diffusion coefficient in differentiating benign from malignant uterine endometrial cavity lesions: initial results. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(2):384–389. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamai K, Koyama T, Saga T, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of uterine endometrial cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(3):682–687. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheu MH, Chang CY, Wang JH, Yen MS. Preoperative staging of cervical carcinoma with MR imaging: a reappraisal of diagnostic accuracy and pitfalls. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(9):1828–1833. doi: 10.1007/s003300000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagenaar HC, Trimbos JB, Postema S, et al. Tumor diameter and volume assessed by magnetic resonance imaging in the prediction of outcome for invasive cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82(3):474–482. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiraiwa M, Joja I, Asakawa T, et al. Cervical carcinoma: efficacy of thin-section oblique axial T2-weighted images for evaluating parametrial invasion. Abdominal imaging. 1999;24(5):514–519. doi: 10.1007/s002619900552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawighorst H, Knapstein PG, Weikel W, et al. Cervical carcinoma: comparison of standard and pharmacokinetic MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;201(2):531–539. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen J, Zhang Y, Liang B, Yang Z. The utility of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in cervical cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naganawa S, Sato C, Kumada H, Ishigaki T, Miura S, Takizawa O. Apparent diffusion coefficient in cervical cancer of the uterus: comparison with the normal uterine cervix. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicolet V, Carignan L, Bourdon F, Prosmanne O. MR imaging of cervical carcinoma: a practical staging approach. Radiographics. 2000;20(6):1539–1549. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.6.g00nv111539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y, Liu H, Bai X, et al. Differentiation of metastatic from non-metastatic lymph nodes in patients with uterine cervical cancer using diffusion-weighted imaging. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi HJ, Kim SH, Seo SS, et al. MRI for pretreatment lymph node staging in uterine cervical cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):W538–543. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin G, Ho KC, Wang JJ, et al. Detection of lymph node metastasis in cervical and uterine cancers by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(1):128–135. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitajima K, Suzuki K, Senda M, et al. Preoperative nodal staging of uterine cancer: is contrast-enhanced PET/CT more accurate than non-enhanced PET/CT or enhanced CT alone? Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25(7):511–519. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reinhardt MJ, Ehritt-Braun C, Vogelgesang D, et al. Metastatic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer: detection with MR imaging and FDG PET. Radiology. 2001;218(3):776–782. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr19776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaur H, Choi H, You YN, et al. MR imaging for preoperative evaluation of primary rectal cancer: practical considerations. Radiographics. 2012;32(2):389–409. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]