Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae has been described in Southeast Asia, but has only recently begun to emerge in North America. The hypermucoviscous strain of K. pneumoniae is a particularly virulent strain known to cause devastatingly invasive infections, including necrotizing fasciitis. Here we present the first known case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae in North America.

INTRODUCTION

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a member of the enterobacteriacea family of gram-negative rods that are found primarily in the human gastrointestinal tract. The most common forms of Klebsiella infection are hospital- acquired urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and bacteremia. Much of the recent literature surrounding K. pneumoniae has been in regards to its role as a carrier of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), and more recently, as the predominant carbapenem resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE) species. CRE is a new class of multi-drug resistant species that tend to infect elderly patients after prolonged hospital stays or in long-term care facilities.1 The substantial mortality associated with CRE infections is likely due the lack of effective treatments and underlying vulnerability of the patients, rather than virulence of the bacteria.1

This case report describes a strain of K. pneumoniae, referred to as hypermucoviscous, that is distinctly different from CRE. Hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae, unlike CRE, is community acquired, highly virulent and essentially pansensitive.2 Hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae causes invasive infections, including liver abscess, endopthalmitis, meningitis, empyema, and necrotizing fasciitis, that occur primarily in Southeast Asia. Here we report a case of monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis caused by hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae in a Filipino woman who presented to our public hospital in Oakland, California. While there have been limited reports of infection with this unusual K. pneumoniae strain outside of Asia, to our knowledge this is the first report of necrotizing fasciitis caused by confirmed hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae in North America.

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old Filipino female with no known past medical history presented to an emergency department in Oakland, California, for neck swelling, fever, and difficulty breathing. She had been experiencing these symptoms for two weeks, with the neck swelling becoming progressively worse. On physical exam the patient appeared ill with a heart rate of 139, blood pressure of 87/36 and temperature 101.1, indicating septic shock. Physical exam revealed a large fluctuant mass over the left lateral neck. The center of this mass exhibited blackish discoloration and skin necrosis. Swelling and crepitus extended to the anterior and posterior neck, left shoulder and anterior chest wall.

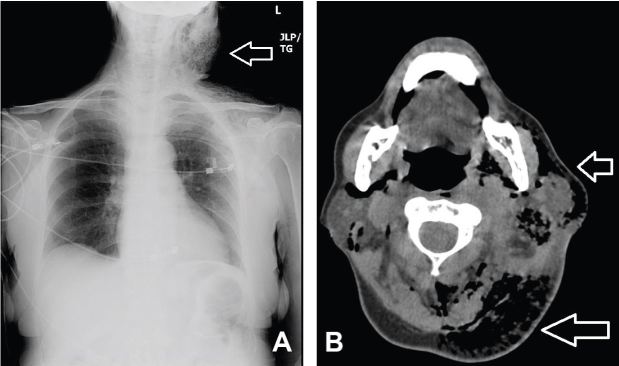

Initial laboratory evaluation showed a white blood cell count of 22.9thou/mcL, Hemoglobin of 14.8g/dL, and platelets of 359thou/mcL. Notable chemistries were sodium of 125mmol/L, potassium 4.9mmol/L, chloride 110mmol/L, bicarbonate less than 5mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 41mg/dL, creatinine 2.5mg/dL, glucose 917mg/dL, and lactic acid 3.5mmol/L. Urinalysis showed glucosuria and ketonuria. CT of chest and neck revealed extensive subcutaneous emphysema throughout the left lateral upper chest wall, left shoulder region, anterior mediastinum and throughout the superficial and deep spaces of the neck (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A, Chest radiograph and B, neck computed tomography image at level of C2, both demonstrating left-sided neck mass with extensive subcutaneous emphysema (open arrows).

The patient was taken to the operating room for debridement and was discovered to have necrotic deep muscle tissue and fascia. Intraoperative biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis, with necrotic and purulent material found in the dermis, subcutaneous tissues, and fascia.

During the patient’s hospital stay, she required numerous vasopressors and steroids for refractory hypotension, hemodialysis for refractory acidosis and uremia, and was taken to the operating room for debridement a total of three times. The patient expired on her seventh hospital day due to overwhelming sepsis and acidosis.

Cultures of blood, urine, and surgical specimens all grew K. pneumoniae. These isolates were string-test positive, indicating that this was the hypermucoviscous strain. All cultures were resistant to ampicillin, but otherwise were pan susceptible.

DISCUSSION

The distinctive clinical syndrome of invasive hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae, consisting of liver abscesses, bacteremia, and metastatic infection, particularly of the central nervous system, is now well described. To a large extent, the syndrome has been geographically restricted to Southeast Asia. The association of this pathogen with a wider range of invasive infections, including soft tissue abscesses and necrotizing fasciitis has only been recognized more recently with the first description of necrotizing fasciitis appearing in 1996.3 While much of the existing literature consists of case reports,4–8 a recent large case series from Taiwan systematically evaluated K. pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis.9 In this single hospital study, K. pneumoniae accounted for 17% of monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis cases as compared to 22% due to S. aureus and 18% due to group A Streptococcus. Fifteen K. pneumoniae cases were compared to a similar number caused by group A Streptococcus – an organism more traditionally associated with necrotizing fasciitis. The investigators found that K. pneumoniae cases exhibited higher mortality and higher rates of bacteremia and that patients were more likely to be immunocompromised, with 80% having diabetes.

Outside of Asia, K. pneumoniae has just begun to emerge as a cause of necrotizing fasciitis. Three cases have been described in Europe.10–12 The first case of K. pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis described in North America was in 2007, in which a Cambodian man with travel to Cambodia six months prior was diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis and died in three days.13 Two subsequent reports described K. pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis in patients who had no recent travel to Asia and were not of Asian descent.14,15 A recent North American case series reported on six liver transplant recipients, who developed K. pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis, all of whom died.16 There is one report specifically of K. pneumoniae cervical necrotizing fasciitis, similar to our case, that required 12 surgical debridements with the patient surviving.17

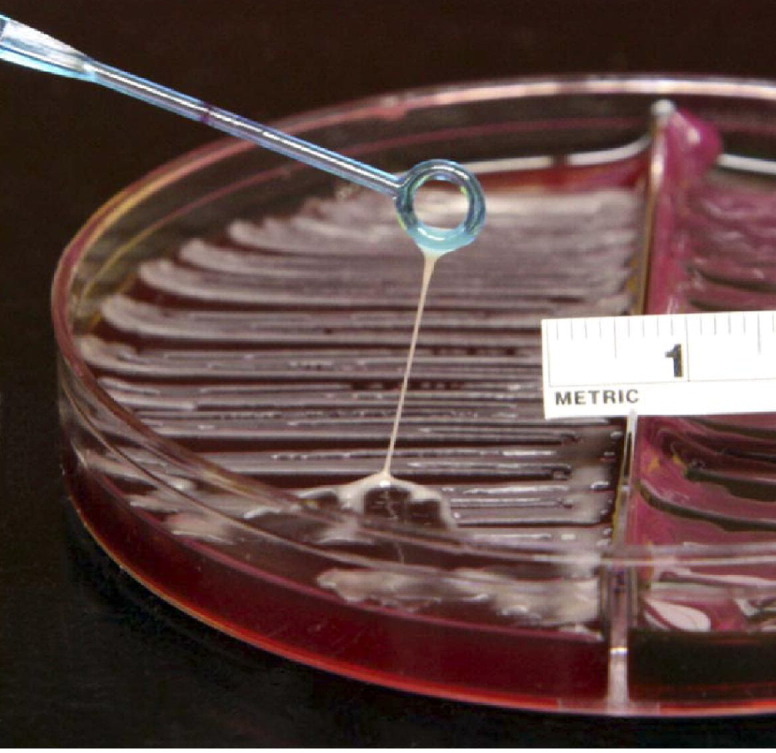

Ours is the first case report of K. pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis in the North America to confirm the hypermucoviscous phenotype. Hypermucoviscous strains are identified in the laboratory with a simple string test, in which a colony is lifted with a loop, producing a string longer than 5mm (Figure 2). The phenotype is associated with the rmpA and magA genes;18 although we did not perform genotyping in this case, we have previously shown the hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae isolates from our hospital were rmpA positive.19 The hypermucoviscous phenotype is thought to confer virulence by a number of mechanisms, including its ability to resist phagocytosis, and both complement and neutrophil-mediated killing, and its ability to more efficiently acquire iron.20,21 These virulence factors lead to a destructive clinical syndrome, often with multiple infectious metastases.20–22 It is likely that most of the community-acquired invasive K. pneumoniae infections recently reported in North America, including the previously reported necrotizing fasciitis cases, were also due to the hypermucoviscous strain, but that string testing was simply not performed. Hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae strains are invariably cephalosporin susceptible, so the finding of broad antibiotic susceptibility in a K. pneumoniae isolate from a community-acquired invasive infection represents indirect evidence that it is a hypermucoviscous strain. As expected, most of the studies of K. pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis outside of Asia reported similar antibiotic susceptibility profiles that fit this pattern.10,13–15

Figure 2.

Example of a positive string test (>5mm string) indicating the hypermucoviscous phenotype.

We previously reported 13 cases of invasive infection caused by hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae.19,23 In our series, multiple types of infectious were found, including neck abscesses, pyelonephritis, brain abscesses, pneumonia, liver abscesses, and cholecystitis. Including the current case, four patients with skin and soft tissue infections due to hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae have been seen since 2007 at our urban public hospital in Northern California.

Interestingly, hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae still remains largely confined to Asia and cases in North America have occurred disproportionately in patients of Asian descent. This has raised speculation as to a genetic susceptibility to colonization and/or infection.21 Data from stool samples from healthy Chinese and Korean adults residing throughout Asia have also suggested that a small percentage of Asians are colonized with hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae.21 Alternatively, patients may simply acquire hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae from living in or traveling to endemic areas. Regardless, it seems that being of Asian descent and recent travel to Asia are the most important risk factors, along with diabetes mellitus, for developing a hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae infection.

Our West Coast urban safety net hospital serves a large Southeast Asian population, including recent immigrants, which likely accounts for the large number of cases we have seen. Yet it is also likely that hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae has made an unrecognized emergence elsewhere in northern California and perhaps elsewhere in North America. While we predicted in 2009 that this pathogen was likely to emerge dramatically in the U.S., subsequent reports have been limited. Ultimately, routinely testing for and identifying hypermucoviscosity in K. pneumoniae isolates has limited clinical importance in changing early management, especially for necrotizing soft tissue infections, as aggressive sepsis care, early empiric broad spectrum antibiotics, and prompt source control remain priorities in the treatment of necrotizing soft tissue infections, regardless of etiology. On the other hand, microbiologic surveillance for emerging pathogens is a potentially important role of emergency departments, especially those located in communities with large immigrant populations.24,25 The appearance of a new and virulent pathogen here in North America will certainly have public health implications; however, it is difficult to predict what these might be, as confirmed cases are sparse in number and based on our suspicions, other cases are potentially not being recognized. We therefore advocate that string testing be performed routinely on all K. pneumoniae isolates. In addition to identifying this clinically distinctive syndrome and thereby prompting a search for metastatic infections, routine string testing of K. pneumoniae isolates might illuminate the connection with the Southeast Asian data and clarify whether this pathogen is emerging rapidly outside of Asia.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, DO

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perez F, Van Duin D. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: A menace to our most vulnerable patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;8:225–233. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.80a.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HC, Chuang YC, Yu WL, et al. Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: An association with invasive syndrome in patients with community acquired bacteremia. J Intern Med. 2006;259:606–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou FF, Kou HK. Endogenous endopthalmitis associated with pyogenic hepatic abscess. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu BS, Lau YJ, Shi ZY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1360–1361. doi: 10.1086/313471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho PL, Tang WM, Yuen KY. Klebsiella pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis associated with diabetes and liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:989–990. doi: 10.1086/313791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CH, Kurup A, Wang YS, et al. Four cases of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Klebsiella species. Eur J of Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:403–407. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenny K, Boris F, Wing-Yuk I. Klebsiella pneumoniae causing necrotizing fasciitis in a patient with thalassemia major. J Orthop Trauma Rehabil. 2011;15:25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mita N, Narahara H, Okawa M, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis following psoas muscle abscess caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:565–568. doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng N, Yu Y, Tai H, et al. Recent trend of necrotizing fasciitis in Taiwan: Focus on monomicrobial Klebsiella pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:930–939. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunnarson GL, Brandt PB, Gad D, et al. Monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis in a white male caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1519–1521. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whallet EJ, Stevenson JH, Wilmshurst AD. Necrotising fasciitis of the extremity. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2010;63:469–473. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decre D, Verdet C, Emirian A, et al. Emerging severe and fatal infectious due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in two university hospitals in France. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3012–3014. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00676-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohler JE, Hutches MP, Sadow PM, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis and septic arthritis: An appearance in the western hemisphere. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2007;8:227–232. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelesidis T, Tsiodras S. Postirradiation Klebsiella pneumoniae-Associated necrotizing fasciitis in the Western Hemisphere: A rare but life threatening clinical entity. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:217–224. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181a393a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persichino J, Tran R, Sutjita M, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis in a Latin American male. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1614–1616. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.043638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rana MM, Sturdevant M, Patel G, et al. Klebsiella necrotizing soft tissues infections in liver transplant recipients: a case series. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15:157–163. doi: 10.1111/tid.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas AJ, Mong S, Golub, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae cervical necrotizing fasciitis originating as an abscess. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33:764–766. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu WL, Ko WC, Cheng KC, et al. Association between rmpA and magA genes and clinical syndromes caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1351–1358. doi: 10.1086/503420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frazee BW, Hansen S, Lambert L. Invasive infection with hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae: Multiple cases presenting to a single emergency department in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:639–642. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SS. Klebsiella pneumoniae is an emerging pathogen in necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:940–942. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shon AS, Bajwa R, Russo TA. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence. 2013;4:107–118. doi: 10.4161/viru.22718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawai T. Hypermucoviscosity: An extremely stick phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with emerging destructive tissues abscess syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1359–1361. doi: 10.1086/503429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCabe R, Lambert L, Frazee B. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1490–1491. doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suyama J, Sztajnkrycer M, Lindsell C, et al. Surveillance of Infectious Disease Occurrences in the community: An analysis of symptom presentation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:753–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talan DA, Moran GJ, Mower WR, et al. EMERGEncy ID NET: an emergency department-based emerging infectious sentinel network. The EMERGEncy ID NET Study Group. Ann of Emerg Med. 1998;32:703–711. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]