Abstract

The task of estimating a Gaussian graphical model in the high-dimensional setting is considered. The graphical lasso, which involves maximizing the Gaussian log likelihood subject to a lasso penalty, is a well-studied approach for this task. A surprising connection between the graphical lasso and hierarchical clustering is introduced: the graphical lasso in effect performs a two-step procedure, in which (1) single linkage hierarchical clustering is performed on the variables in order to identify connected components, and then (2) a penalized log likelihood is maximized on the subset of variables within each connected component. Thus, the graphical lasso determines the connected components of the estimated network via single linkage clustering. The single linkage clustering is known to perform poorly in certain finite-sample settings. Therefore, the cluster graphical lasso, which involves clustering the features using an alternative to single linkage clustering, and then performing the graphical lasso on the subset of variables within each cluster, is proposed. Model selection consistency for this technique is established, and its improved performance relative to the graphical lasso is demonstrated in a simulation study, as well as in applications to a university webpage and a gene expression data sets.

Keywords: single linkage clustering, hierarchical clustering, sparsity, network, high-dimensional setting

1. Introduction

Graphical models have been extensively used in various domains, including modeling of gene regulatory networks and social interaction networks. A graph consists of a set of p nodes, corresponding to random variables, as well as a set of edges joining pairs of nodes. In a conditional independence graph, the absence of an edge between a pair of nodes indicates a pair of variables that are conditionally independent given the rest of the variables in the data set, and the presence of an edge indicates a pair of conditionally dependent nodes. Hence, graphical models can be used to compactly represent complex joint distributions using a set of local relationships specified by a graph. Throughout the rest of the text, we will focus on Gaussian graphical models.

Let X be a n × p matrix where n is the number of observations and p is the number of features; the rows of X are denoted as x1, …, xn. Assume that where Σ is a p × p covariance matrix. Under this simple model, there is an equivalence between a zero in the inverse covariance matrix and a pair of conditionally independent variables [18]. More precisely, (Σ−1)jj′ = 0 for some j ≠ j′ if and only if the jth and j′th features are conditionally independent given the other variables.

Let S denote the empirical covariance matrix of X, defined as S = XT X/n. A natural way to estimate Σ−1 is via maximum likelihood. This approach involves maximizing

with respect to Θ, where Θ is an optimization variable. The solution Θ̂ = S−1 serves as an estimate for Σ−1. However, in the high-dimensional setting where p ≫ n, S is singular and is not invertible. Furthermore, even if S is invertible, Θ̂ = S−1 typically contains no elements that are exactly equal to zero. This corresponds to a graph in which the nodes are fully connected to each other; such a graph does not provide useful information. To overcome these problems, Yuan and Lin [37] proposed to maximize the penalized log likelihood

| (1) |

with respect to Θ, penalizing only the off-diagonal elements of Θ. A number of algorithms have been proposed to solve (1) [among others, 6, 27, 28, 36, 37]. Note that some authors have considered a slight modification to (1) in which the diagonal elements of Θ are also penalized. We refer to the maximizer of (1) as the graphical lasso solution; it serves as an estimate for Σ−1. When the nonnegative tuning parameter λ is sufficiently large, the estimate will be sparse, with some elements exactly equal to zero. These zero elements correspond to pairs of variables that are estimated to be conditionally independent.

Witten et al. [32] and Mazumder and Hastie [19] presented the following result:

Theorem 1

The connected components of the graphical lasso solution with tuning parameter λ are the same as the connected components of the undirected graph corresponding to the p × p adjacency matrix A(λ), defined as

Here 1(|Sjj′|>λ) is an indicator variable that equals 1 if |Sjj′| > λ, and equals 0 otherwise. For instance, consider a partition of the features into two disjoint sets, D1 and D2. Theorem 1 indicates that if |Sjj′| ≤ λ for all j ∈ D1 and all j′ ∈ D2, then the features in D1 and D2 are in two separated connected components of the graphical lasso solution. Theorem 1 reveals that solving problem (1) boils down to two steps:

Identify the connected components of the undirected graph with adjacency matrix A.

Perform graphical lasso with parameter λ on each connected component separately.

In this paper, we will show that identifying the connected components in the graphical lasso solution – that is, Step 1 of the two-step procedure described above – is equivalent to performing single linkage hierarchical clustering (SLC) on the basis of a similarity matrix given by the absolute value of the elements of the empirical covariance matrix S. However, we know that SLC tends to produce trailing clusters in which individual features are merged one at a time, especially if the data are noisy and the clusters are not clearly separated [9]. In addition, the two steps of the graphical lasso algorithm are based on the same tuning parameter, λ, which can be suboptimal. Motivated by the connection between the graphical lasso solution and single linkage clustering, we therefore propose a new alternative to the graphical lasso. We will first perform clustering of the variables using an alternative to single linkage clustering, and then perform the graphical lasso on the subset of variables within each cluster. Our approach decouples the cutoff for the clustering step from the tuning parameter used for the graphical lasso problem. This results in improved detection of the connected components in high-dimensional Gaussian graphical models, leading to more accurate network estimates. Based on this new approach, we also propose a new method for choosing the tuning parameter for the graphical lasso problem on the subset of variables in each cluster, which results in consistent identification of the connected components in the graph.

In a recent proposal, Hsieh et al. [10] considered speeding up the graphical lasso algorithm using a clever choice of initialization. They cluster the features, perform the graphical lasso on the features within each cluster, and then aggregate the solutions in order to initialize a full graphical lasso algorithm. Hsieh et al. [10]’s proposal and the proposal of our paper both involve clustering the features and then performing the graphical lasso on each cluster. However, Hsieh et al. [10]’s final estimator is the graphical lasso, whereas we propose an alternative estimator that can outperform the graphical lasso.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we establish a connection between the graphical lasso and single linkage clustering. In Section 3, we present our proposal for cluster graphical lasso, a modification of the graphical lasso that involves discovery of the connected components via an alternative to SLC. We prove model selection consistency of our procedure in Section 4. Simulation results are in Section 5, and Section 6 contains an application of cluster graphical lasso to a webpage data set and a gene expression data set. The Discussion is in Section 7.

2. Graphical lasso and single linkage clustering

We assume that the columns of X have been standardized to have mean zero and variance one. Let S̃ denote the p × p matrix whose elements take the form where Xj is the jth column of X.

Theorem 2

Let C1, …, CK denote the clusters that result from performing single linkage hierarchical clustering (SLC) using similarity matrix S̃, and cutting the resulting dendrogram at a height of 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1. Let D1, …, DR denote the connected components of the graphical lasso solution with tuning parameter λ. Then, K = R, and there exists a permutation π such that Ck = Dπ(k) for k = 1, …, K.

Theorem 2, which is proven in the Supplementary Materials, establishes a surprising connection between two seemingly unrelated techniques: the graphical lasso and SLC. The connected components of the graphical lasso solution are identical to the clusters obtained by performing SLC based on the similarity matrix S̃.

Theorem 2 refers to cutting a dendrogram that results from performing SLC using a similarity matrix. This concept is made clear in Figure 1. In this example, S̃ is given by

Figure 1.

SLC is performed on the similarity matrix (2). The resulting dendrogram is shown, as are the clusters that result from cutting the dendrogram at various heights.

| (2) |

For instance, cutting the dendrogram at a height of λ = 0.79 results in three clusters, {1, 2}, {3}, and {4}. Theorem 2 further indicates that these are the same as the connected components that result from applying the graphical lasso to S with tuning parameter λ.

3. The cluster graphical lasso

3.1. A simple alternative to SLC

Motivated by Theorem 2, and the fact that the clusters identified by SLC tend to have an undesirable chain structure [9], we now consider performing clustering before applying the graphical lasso to the set of features within each cluster.

The cluster graphical lasso (CGL) is presented in Algorithm 1. We partition the features into K clusters based on S̃, and then perform the graphical lasso estimation procedure on the subset of variables within each cluster. Provided that the true network has several connected components, and that the clustering technique that we use in Step 1 is better than SLC, we expect CGL to outperform graphical lasso.

Algorithm 1.

Cluster graphical lasso (CGL)

|

Furthermore, we note that by Theorem 2, the usual graphical lasso is a special case of Algorithm 1, in which the clusters in Step 1 are obtained by cutting the SLC dendrogram at a height λ, and in which λ1 = … = λK = λ in Step 2(a).

The advantage of CGL over the graphical lasso is two-fold.

As mentioned earlier, SLC performs poorly in the finite-sample setting, often resulting in estimated graphs with one large connected component, and many very small ones. Therefore, identifying the connected components using a better clustering procedure may yield improved results.

As revealed by Theorems 1 and 2, the graphical lasso effectively couples two operations using a single tuning parameter λ: identification of the connected components in the network estimate, and identification of the edge set within each connected component. Therefore, in order for the graphical lasso to yield a solution with many connected components, each connected component must typically be extremely sparse. CGL allows for these two operations to be decoupled, often to advantage.

3.2. Interpretation of CGL as a penalized log likelihood problem

Consider the optimization problem

| (3) |

where

By inspection, the solution to this problem is the CGL network estimate. In other words, the CGL procedure amounts to solving a penalized log likelihood problem in which we impose an arbitrarily large penalty on |Θjj′| if the jth and j′th features are in different clusters. In contrast, if wjj′ = λ in (3), then this amounts to the graphical lasso optimization problem (1).

3.3. Tuning parameter selection

CGL involves several tuning parameters: the number of clusters K and the sparsity parameters λ1, …, λK. It is well-known that selecting tuning parameters in unsupervised settings is a challenging problem [for an overview and several past proposals, see, e.g., 7, 9, 20, 22, 30]. Algorithm 2 outlines an approach for selecting K. It involves leaving out random elements from the matrix S̃ and performing clustering. The clusters obtained are then used to impute the left-out elements, and the corresponding mean squared error is computed. Roughly speaking, the optimal K is that for which the mean squared error is smallest. This is related to past approaches in the literature for performing tuning parameter selection in the unsupervised setting by recasting the unsupervised problem as a supervised one [see, e.g., 23, 33, 34]. The numerical investigation in Section 5 indicates that our algorithm results in reasonable estimates of the number of connected components, and that the performance of CGL is not very sensitive to the value of K.

In Corollary 3, we propose a choice of λ1, …, λK that guarantees consistent recovery of the connected components.

4. Consistency of cluster graphical lasso

In this section, we establish that CGL consistently recovers the connected components of the underlying graph, as well as its edge set. A number of authors have shown consistency of the graphical lasso solution for different matrix norms [3, 12, 27]. Lam and Fan [12] further showed that under certain conditions, the graphical lasso solution is sparsistent, i.e., zero entries of the inverse covariance matrix are correctly estimated with probability tending to one. Lam and Fan [12] also showed that there is no choice of λ that can simultaneously achieve the optimal rate of sparsistency and consistency for estimating Σ−1, unless the number of non-zero elements in the off-diagonal entries is no larger than O(p). In more recent work, Ravikumar et al. [25] studied the graphical lasso estimator under a variety of tail conditions, and established that the procedure correctly identifies the structure of the graph, if an incoherence assumption holds on the Hessian of the inverse covariance matrix, and if the minimum off-diagonal nonzero entry of the inverse covariance matrix is sufficiently large. We will restate these conditions more precisely in Lemma 2.

Here, we focus on model selection consistency of CGL, in the setting where the inverse covariance matrix is block diagonal. To establish the model selection consistency of CGL, we need to show that (i) CGL correctly identifies the connected components of the graph, and (ii) it correctly identifies the set of edges (i.e., the set of non-zero values of the inverse covariance matrix) within each of the connected components. More specifically, we first show that CGL with clusters obtained from performing SLC, average linkage hierarchical clustering (ALC), or complete linkage hierarchical clustering (CLC) based on S̃ consistently identifies the connected components of the graph. Next, we adapt the results of Ravikumar et al. [25] on model selection consistency of graphical lasso in order to establish the rates of convergence of the CGL estimate.

As we will show below, our results highlight the potential advantages of CGL in the settings where the underlying inverse covariance matrix is block diagonal (i.e., the graph consists of multiple connected components). As a byproduct, we also address the problem of determining the appropriate set of tuning parameters for penalized estimation of the inverse covariance matrix in high dimensions: given knowledge of K, the number of connected components in the graph, we suggest a choice of λ1, …, λK for CGL that leads to consistent identification of the connected components in the underlying network. In the context of the graphical lasso, Banerjee et al. [1] have suggested a choice of λ such that the probability of adding edges between two disconnected components is bounded by α, given by

| (7) |

where tn−2(α) denotes the (100 − α) percentile of the Student’s t-distribution with n−2 degrees of freedom, and Sii is the empirical variance of the ith variable. The proposal of Banerjee et al. [1] is based on an earlier result by Meinshausen and Bühlmann [21], who suggested a similar choice of λ for estimating the edge set of the graph using the neighborhood selection approach. Note that (7) is fundamentally different from our proposal, as this choice of λ does not guarantee that each connected component is not broken into several distinct connected components. In fact, empirical studies have found that the choice of λ in (7) may result in an estimated graph that is too sparse [29].

Algorithm 2.

Selecting the number of clusters K

|

Before we continue, we summarize some notation that will be used in Sections 4.1 and 4.2. Let X be a n × p matrix; the rows of X are denoted as x1, …, xn, where and Σ is a block diagonal covariance matrix with K blocks. We let Ck be the feature set corresponding to the kth block. (In previous sections, C1, …, CK denoted a set of estimated clusters; in this section only, C1, …, CK are the true and in practice unknown clusters.) Also, let Ĉ1, …, ĈK denote a set of estimated clusters obtained from performing SLC, ALC, or CLC. In what follows, we use the terms clusters and connected components interchangeably. Let S̃ = |XTX/n| be the absolute empirical covariance matrix. Proofs are in the Supplementary Materials.

4.1. Consistent recovery of the connected components

We now present some results on the recovery of the connected components of Σ−1 by SLC, ALC, or CLC, as well as its implications for the CGL procedure.

Lemma 1

Assume that Σ is a block diagonal matrix with K blocks and diagonal elements Σii ≤ M ∀i, where M is some constant. Furthermore, let

for some t > 0 such that c2t2 > 2. Then performing SLC, ALC, or CLC with similarity matrix S̃ satisfies P(∃k: Ĉk ≠ Ck) ≤ c1 p2−c2t2.

Lemma 1 establishes the consistency of identification of connected components by performing hierarchical clustering using SLC, ALC, or CLC, provided that n = Ω(log p) as n, p → ∞, and provided that no within-block element of Σ is too small in absolute value. Bühlmann et al. [2] also commented on the consistency of hierarchical clustering.

Let S̃1, …, S̃K denote the K blocks of S̃ corresponding to the features in Ĉ1, …, ĈK. In other words, S̃k is a |Ĉk| × |Ĉk| matrix. The following corollary on selecting the tuning parameter λ1, …, λK for CGL is a direct consequence of Lemma 1 and Theorem 1.

Corollary 3

Assume that the diagonal elements of Σ are bounded and that

Let λ̄k be the smallest value that cuts the dendrogram resulting from applying SLC to S̃k into two clusters. Performing CGL with SLC, ALC, or CLC and penalty parameter λk ∈ [0, λ̄k) for k = 1, …, K leads to consistent identification of the K connected components if n = Ω(log p) as n, p → ∞.

Corollary 3 implies that one can consistently recover the K connected components by (a) performing hierarchical clustering based on S̃ to obtain K clusters and (b) choosing the tuning parameter λk ∈ [0, λ̄k) in Step 2(b) of Algorithm 1 for each of the K clusters. However, Corollary 3 does not guarantee that this set of tuning parameters λ1, …, λK will identify the correct edge set within each connected component. We now establish such a result.

4.2. Model selection consistency of CGL

The following theorem combines Lemma 1 with results on model selection consistency of the graphical lasso [25] in order to establish the model selection consistency of CGL. We start by introducing some notation and stating the assumptions needed.

Let Θ = Σ−1. Θ specifies an undirected graph with K connected components; the kth connected component has edge set Ek = {(i, j) ∈ Ck: i ≠ j, θij ≠ 0}. Let . Also, let Fk = Ek ∪ {(j, j) : j ∈ Ck}; this is the union of the edge set and the diagonal elements for the kth connected component. Define dk to be the maximum degree in the kth connected component, and let d = maxk dk. Also, define pk = |Ck|, pmin = mink pk, and pmax = maxk pk.

Assumption 1 involves the Hessian of Equation 1, which takes the form

where ⊗ is the Kronecker matrix product, and Γ(k) is a matrix. With some abuse of notation, we define as the |A| × |B| submatrix of Γ(k) whose rows and columns are indexed by A and B respectively, i.e., .

Assumption 1

There exists some α ∈ (0, 1] such that for all k = 1, …, K,

Assumption 2

For θmin:= min(i,j)∈E |θij|, the minimum non-zero off-diagonal element of the inverse covariance matrix,

as n and p grow.

We now present a lemma on model selection consistency of CGL. It relies heavily on Theorem 2 of Ravikumar et al. [25], to which we refer the reader for details.

Lemma 2

Assume that Σ satisfies the conditions in Lemma 1. Further, assume that Assumptions 1 and 2 are satisfied, and that ||Σk||∞ and are bounded, where ||A||∞ denotes the ℓ∞ norm of A. Assume K = O(pmin), τ > 3, where τ is a user-defined parameter, and

Let Ê denote the edge set from the CGL estimate using SLC, ALC, or CLC with K clusters and . Then Ê = E with probability at least .

Remark 1

Lemma 2 states that CGL with SLC can improve upon existing model selection consistency results for the graphical lasso. Recall that Theorem 2 indicates that graphical lasso is a two-step procedure in which SLC precedes precision matrix estimation within each cluster. However, the two steps in the graphical lasso procedure involve a single tuning parameter, λ. The improved rates for CGL in Lemma 2 are achieved by decoupling the choice of tuning parameters in the two steps.

Remark 2

Note that the assumption of Lemma 1 that Σij ≠ 0 for all (i, j) ∈ Ck does not require the underlying conditional independence graph for that connected component to be fully connected. For example, consider the case where connected components of the underlying graph are forests, with non-zero partial correlations on each edge of the graph. Note that there exists a unique path

of length q between each pair of elements i and j in the same block. Then by Theorem 1 of Jones and West [11],

of length q between each pair of elements i and j in the same block. Then by Theorem 1 of Jones and West [11],

for some constant c depending on the path

and the determinant of the precision matrix. By the positive definiteness of precision matrix, and the fact that partial correlations along the edges of the graph are non-zero, it follows that Σij ≠ 0 for all i and j in the same block.

and the determinant of the precision matrix. By the positive definiteness of precision matrix, and the fact that partial correlations along the edges of the graph are non-zero, it follows that Σij ≠ 0 for all i and j in the same block.

Remark 3

The convergence rates in Lemma 2 can result in improvements over existing rates for the graphical lasso estimator. For instance, suppose the graph consists of K = ma connected components of size pk = mb each, for positive integers m, a, and b such that m > 1 and a < b. Also, assume that d = m. Then, based on the results of Ravikumar et al. [25], consistency of the graphical lasso requires n = Ω(m2(a + b) log(m)) samples, whereas Lemma 2 implies that n = Ω(bm2 log(m)) samples suffice for consistent estimation using CGL.

Remark 3 is not surprising. The reduction in the required sample size for CGL is achieved from the extra information on the number of connected components in the graph. This result suggests that decoupling the identification of connected components and estimation of the edges improves estimation of Gaussian graphical models in the settings where Σ−1 is block diagonal. The results in the next two sections provide empirical evidence in support of these findings.

5. Simulation study

In this section, we compare CGL with ALC to the graphical lasso. We also include a comparison to the adaptive graphical lasso [5] and reweighted graphical lasso [16]. The adaptive graphical lasso is a two-step procedure: (1) estimate the inverse covariance matrix using the graphical lasso, and (2) refit the graphical lasso with a weighted tuning parameter based on the initial estimate. On the other hand, the goal of the reweighted graphical lasso is to estimate a graph with hub nodes (nodes with many connections). The procedure involves solving a sequence of graphical lasso problems, where the tuning parameters for highly-connected nodes are decreased in each iteration. Both the adaptive graphical lasso and reweighted graphical lasso are intended to reduce the bias introduced by the ℓ1 penalty.

We consider two scenarios in which Σ−1 is either exactly or approximately block diagonal in the following sections.

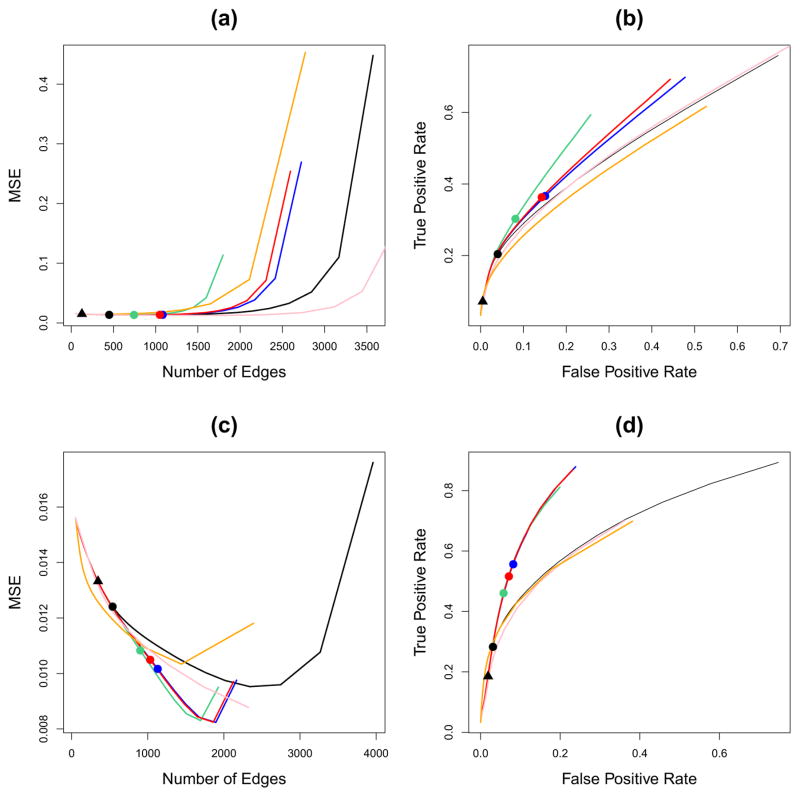

5.1. Σ−1 block diagonal

We generated a n × p data matrix X according to , where Σ−1 is a block diagonal inverse covariance matrix with two equally-sized blocks, and sparsity level s = 0.4 within each block, generated using Algorithm 3. We first standardized the variables to have mean zero and variance one. Then, we performed the graphical lasso, adaptive graphical lasso, and the reweighted graphical lasso with tuning parameter λ ranging from 0.01 to 1. For CGL, we use ALC with (a) the tuning parameter K selected using Algorithm 2 and (b) K = {2, 4}. For simplicity, we chose λ1 = … = λK = λ where λ ranges from 0.01 to 1. We considered two cases in our simulation: n = 50, p = 100 and n = 200, p = 100. Results are presented in Figure 2. More extensive simulation results are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 2.

Results from graphical lasso, adaptive graphical lasso, reweighted graphical lasso, CGL using ALC with various values of K, and CGL with K selected automatically using Algorithm 2, averaged over 200 iterations. The true graph is sparse with two connected components. (a): Plot of average mean squared error of estimated inverse covariance matrix against the average number of non-zero edges with n = 50, p = 100. (b): ROC curve for the number of edges: true positive rate = (number of correctly estimated non-zero)/(total number of non-zero) and false positive rate = (number of incorrectly estimated non-zero)/(total number of zero) with n = 50, p = 100. (c)–(d): As in (a)–(b) with n = 200, p = 100. The solid circles indicate λ = mink λ̄k − ε from Corollary 3 and the triangle indicates the choice of λ proposed by Banerjee et al. [1]. Colored lines correspond to the graphical lasso (——); CGL using ALC, with K=2 (

); CGL using ALC, with K=4 (

); CGL using ALC, with K=4 (

); CGL using ALC, with K from Algorithm 2 (

); CGL using ALC, with K from Algorithm 2 (

); adaptive graphical lasso (

); adaptive graphical lasso (

); and reweighted graphical lasso (

); and reweighted graphical lasso (

).

).

Let λ̄k be as defined in Corollary 3; that is, it is the smallest value of the tuning parameter that will break up the kth connected component asymptotically. The solid circles in Figure 2 correspond to λ= mink λ̄k − ε for some tiny positive ε, i.e., λ is the largest value such that all K of the connected components are consistently identified according to Corollary 3. For instance, the black solid circle corresponds to the largest value of λ such that the graphical lasso consistently identifies the connected components according to Corollary 3. From Corollary 3, any value of λ to the right of the solid circles should consistently identify the connected components. On the other hand, the black triangle in Figure 2 corresponds to the value of λ proposed by Banerjee et al. [1] using α = 0.05, as in Equation 7. This choice of λ guarantees that the probability of adding edges between two disconnected components is bounded by α = 0.05.

From Figures 2(a)-(b), for a given number of non-zero edges, all methods have similar MSEs when the estimated graph is sparse. However, CGL tends to yield a higher fraction of correctly identified non-zero edges, as compared to the other methods. We see that the value of proposed by Banerjee et al. [1] leads to a sparser estimate than does Corollary 3, since the black solid triangle is to the left of the black solid circle. This is consistent with the fact that Banerjee et al. [1]’s choice of λ is guaranteed not to erroneously connect two separate components, but is not guaranteed to avoid erroneously disconnecting a connected component. Moreover, for CGL, the choice of λ from Corollary 3 results in identifying more true edges, compared to the same choice of λ for graphical lasso. This is mainly due to the fact the CGL does better at identifying the connected components.

Algorithm 3.

Generation of sparse inverse covariance matrix Σ−1

|

In Figures 2(a)–(b), n < p and the signal-to-noise ratio is quite low. Consequently, CGL with K = 4 clusters outperforms CGL with K = 2 clusters, even though the true number of connected components is two. This is due to the fact that in this particular simulation set-up with n = 50, ALC with K = 2 has the tendency to produce one cluster containing most of the features and one cluster containing just a couple of features; thus, it may fail to identify the connected components correctly. In contrast, ALC with K = 4 tends to identify the two connected components almost exactly (though it also creates two additional clusters that contain just a couple of features).

Figures 2(c)–(d) indicate that when n = 200 and p = 100, CGL has a lower MSE than do the other methods for a fixed number of non-zero edges. CGL with K = 2 using ALC has the best performance in terms of identifying non-zero edges. The result is not surprising because when n = 200 and p = 100, ALC is able to cluster the features into two clusters almost perfectly. We note that both adaptive graphical lasso and reweighted graphical lasso have lower MSEs than does the graphical lasso. This is because both variants of the graphical lasso de-bias the bias introduced by the ℓ1 penalty.

Overall, CGL leads to more accurate estimation of the inverse covariance matrix than do the graphical lasso, adaptive graphical lasso, and reweighted graphical lasso. This is apparent when the true inverse covariance matrix is block diagonal and the signal-to-noise ratio is high such that CGL is able to identify the connected components accurately. In addition, these results suggest that the method of Algorithm 2 for selecting K, the number of clusters, leads to appropriate choices regardless of the sample size.

5.2. Σ−1 approximately block diagonal

We repeated the simulation from Section 5.1, except that Σ−1 is now approximately block diagonal. That is, we generated data according to Algorithm 3, but between Steps (c) and (d) we altered the resulting Σ−1 such that 2.5% or 10% of the elements outside of the blocks are drawn i.i.d. from a Unif(−0.5, 0.5) distribution. We considered the case when n = 200, p = 100 in this section. Results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

As in Figure 2, with n = 200, p = 100, and Σ−1 approximately block diagonal. (a)–(b): 2.5% of the off-block elements do not equal zero. (c)–(d): 10% of the off-block elements do not equal zero. Colored lines correspond to the graphical lasso (——); CGL using ALC, with K=2 (

); CGL using ALC, with K=4 (

); CGL using ALC, with K=4 (

); CGL using ALC, with K from Algorithm 2 (

); CGL using ALC, with K from Algorithm 2 (

); adaptive graphical lasso (

); adaptive graphical lasso (

); and reweighted graphical lasso (

); and reweighted graphical lasso (

).

).

From Figures 3(a)–(b), when the assumption of block diagonality is only slightly violated, we see that CGL outperforms the graphical lasso. CGL performs similarly to the adaptive graphical lasso and reweighted graphical lasso in terms of MSE, when the estimated graph is sparse. However, as the assumption is increasingly violated, other methods’ performances improve relative to CGL, as is shown in Figures 3(c)–(d).

Recall that CGL is motivated based on the assumption that the true inverse covariance matrix is block diagonal. In those cases, CGL outperforms the other methods.

6. Application to real data sets

We explore two applications of CGL: to a webpage data set in which the features are easily interpreted and to a gene expression data set in which the true conditional dependence among the features is partially known. We choose λ1 = …= λK = λ in CGL for simplicity. An application to an equities data set can be found in Section 3 of the Supplementary Materials.

6.1. University webpages

In this section, we consider the university webpages data set from the “World Wide Knowledge Base” project at Carnegie Mellon University. This data set was preprocessed by Cardoso-Cachopo [4] and previously studied in Guo et al. [8]. It includes webpages from four computer science departments at the following universities: Cornell, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin. In this analysis, we consider only student webpages. This gives us n = 544 student webpages and p = 4800 distinct terms that appear on these webpages.

Let fij be the frequency of the jth term in the ith webpage. We construct a n × p matrix whose (i, j) element is log(1+fij). We selected 100 terms with the largest entropy from 4800 terms, where the entropy of the jth term is defined as and . Each term is then standardized to have mean zero and standard deviation one.

For CGL, we used CLC with tuning parameters K = 5 and λ = 0.25. The estimated network has a total of 158 edges. We then performed the graphical lasso with λ chosen such that the estimated network has the same number of edges as the network estimated by CGL, i.e., 158 edges. The resulting networks are presented in Figure 4. We colored yellow all of the nodes in subnetworks that contained more than one node in the CGL network estimate.

Figure 4.

Network constructed by (a): CGL with CLC with K = 5 and λ = 0.25 (158 edges). (b): graphical lasso with λ chosen to yield 158 edges. Nodes that are in a multiple-node-subnetwork in the CGL solution are colored in yellow.

From Figure 4(a), we see that CGL groups related words into subnetworks. For instance, the terms “computer”, “science”, “depart”, “univers”, “email”, and “address” are connected within a subnetwork. In addition, the terms “office”, “fax”, “phone”, and “mail” are connected within a subnetwork. Other interesting subnetworks include “graduate”-“student”-“work”-“year”-“study” and “school”-“music”. In contrast, the graphical lasso in Figure 4(b) identifies a large subnetwork that contains so many nodes that interpretation is rendered difficult. It fails to identify most of the interesting phrases within subnetworks described.

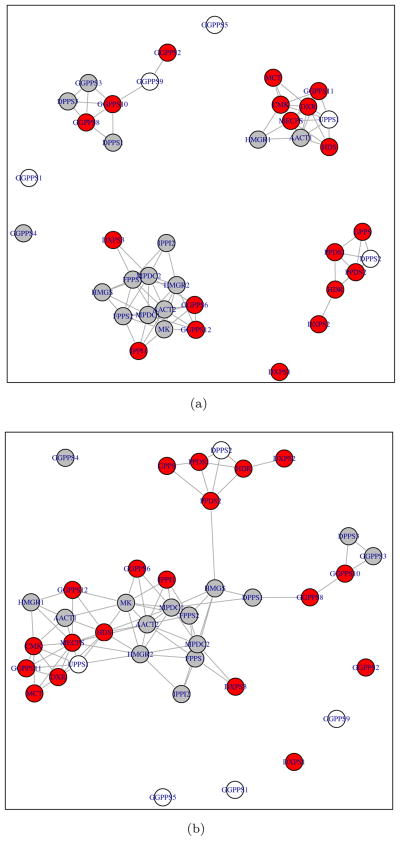

6.2. Arabidopsis thaliana

We consider the Arabidopsis thaliana data set, which consists of gene expression measurements for 118 samples and 39 genes [26]. This data set has been previously studied by Wille et al. [31], Ma et al. [17], and Liu et al. [15]. Plants contain two isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways, the mevalonate acid (MVA) pathway and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway [26]. Of these 39 genes, 19 correspond to MEP pathway, 15 correspond to MVA pathway, and five encode proteins located in the mitochondrion [31]. Our goal was to reconstruct the gene regulatory network of the two isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways. Although we know that both pathways operate independently under normal conditions, interactions between certain genes in the two pathways have been reported [31]. We expect genes within each of the two pathways to be more connected than genes between the two pathways.

We began by standardizing each gene to have mean zero and standard deviation one. For CGL, we set the tuning parameters K = 7 and λ = 0.4. The estimated network has a total of 85 edges. Note that the number of clusters K = 7 was chosen so that the estimated network has several connected components that contain multiple genes. We also performed the graphical lasso with λ chosen to yield 85 edges. The estimated networks are shown in Figure 5. Note that the red nodes, grey nodes, and white nodes in Figure 5 represents the MEP pathway, MVA pathway, and the mitochondrion respectively.

Figure 5.

Pathways identified by (a): CGL with K = 7 and λ = 0.4 (85 edges), and (b): graphical lasso with λ chosen to yield 85 edges. Red, grey, and white nodes represent genes in the MEP pathway, MVA pathway, and mitochondrion, respectively.

From Figure 5(a), we see that CGL identifies several separate subnetworks that might be potentially interesting. In the MEP pathway, the genes DXR, CMK, MCT, MECPS, and GGPPS11 are mostly connected. In addition, genes AACT1 and HMGR1 which are known to be in the MVA pathway are connected to the genes MECPS, CMK, and DXR. Wille et al. [31] suggested that AACT1 and HMGR1 form candidates for cross-talk between the MEP and MVA pathway. For the MVA pathway, genes HMGR2, MK, AACT2, MPDC1, FPPS2, and FPPS1 are closely connected. In addition, there are edges among these genes and genes IPPI1, GGPPS12, and GGPPS6. These findings are mostly in agreement with Wille et al. [31]. In contrast, the graphical lasso results are hard to interpret, since most nodes are part of a very large connected component, as is shown in Figure 5(b).

7. Discussion

We have shown that identifying the connected components of the graphical lasso solution is equivalent to performing SLC based on S̃, the absolute value of the empirical covariance matrix. Based on this connection, we have proposed the cluster graphical lasso, an improved version of the graphical lasso for sparse inverse covariance estimation.

A shortcoming of the graphical lasso is that in order to avoid obtaining a network estimate in which one connected component contains a huge number of nodes, one needs to impose a huge penalty λ in (1). When such a large value of λ is used, the graphical lasso solution tends to contain many isolated nodes as well as a number of small subnetworks with just a few edges. This can lead to an underestimate of the number of edges in the network. In contrast, CGL decouples the identification of the connected components in the network estimate and the identification of the edge structure within each connected component. Hence, it does not suffer from the same problem as the graphical lasso.

In this paper, we have considered the use of hierarchical clustering in the CGL procedure. We have shown that performing hierarchical clustering on S̃ leads to consistent cluster recovery. As a byproduct, we suggest a choice of λ1, …, λK in CGL that yields consistent identification of the connected components. In addition, we establish the model selection consistency of CGL. Detailed exploration of different clustering methods in the context of CGL is left to future work.

Equation 3 indicates that CGL can be interpreted as the solution to a penalized log likelihood problem, where the penalty function has edge-specific weights that are based upon a clustering of the features. This parallels the adaptive lasso [38], in which a consistent estimate of the coefficients is used to weight the ℓ1 penalty in a regression problem. Other weighting schemes could be explored in the context of (3); this is left for future investigation.

Here we have investigated the use of clustering before performing the graphical lasso. As we have seen, this approach is quite natural due to a connection between the graphical lasso and single linkage clustering. However, in principle, one could perform clustering before estimating a graphical model using another technique, such as neighborhood selection [21], sparse partial correlation estimation [24], the nonparanormal [14, 35], or constrained ℓ1 minimization [3]. We leave a full investigation of these approaches for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank two reviewers and an associate editor for helpful comments that improved the quality of this manuscript. We thank Noah Simon for helpful conversations about the connection between graphical lasso and SLC; Jian Guo and Ji Zhu for providing the university webpage data set in Guo et al. [8]; and Han Liu and Tuo Zhao for sharing the equities data set in Liu et al. [13]. This work was supported by NIH Grant DP5OD009145, 1R21GM10171901A1; and NSF Grant DMS-1252624, DMS-1161565.

Footnotes

The reader is referred to the online Supplementary Materials for additional applications to real and simulated data, and to proofs of the theoretical results.

Contributor Information

Daniela Witten, Email: dwitten@uw.edu.

Ali Shojaie, Email: ashojaie@uw.edu.

References

- 1.Banerjee O, El Ghaoui LE, d’Aspremont A. Model selection through sparse maximum likelihood estimation for multivariate Gaussian or binary data. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2008;9:485–516. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bühlmann P, Rütimann P, van de Geer S, Zhang C. Correlated variables in regression: clustering and sparse estimation. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2013;143:1835–1858. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai T, Liu W, Luo X. A constrained ℓ1 minimization approach to sparse precision matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2011;106:594–607. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardoso-Cachopo A. 2009 http://web.ist.utl.pt/acardoso/datasets/

- 5.Fan J, Feng Y, Wu Y. Network exploration via the adaptive LASSO and SCAD penalties. The Annals of Applied statistics. 2009;3:521–541. doi: 10.1214/08-AOAS215SUPP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics. 2007;9:432–441. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon A. Null models in cluster validation. In: Gaul W, Pfeifer D, editors. From data to knowledge. Springer; 1996. pp. 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo J, Levina E, Michailidis G, Zhu J. Joint estimation of multiple graphical models. Biometrika. 2011;98(1):1–15. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Data Mining, Inference and Prediction. Springer Verlag; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh CJ, Banerjee A, Dhillon IS, Ravikumar PK. A divide-and-conquer method for sparse inverse covariance estimation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2012:2330–2338. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones B, West M. Covariance decomposition in undirected Gaussian graphical models. Biometrika. 2005;92:779–786. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam C, Fan J. Sparsistency and rates of convergence in large covariance matrix estimation. Annals of Statistics. 2009;37(6B):4254–4278. doi: 10.1214/09-AOS720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Han F, Yuan M, Lafferty J, Wasserman L. The non-paranormal skeptic. Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Machine Learning..2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Lafferty J, Wasserman L. The nonparanormal: semi-parametric estimation of high dimensional undirected graphs. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2009;10:2295–2328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Xu M, Gu H, Gupta A, Lafferty J, Wasserman L. Forest density estimation. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2011;12:907–951. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Q, Ihler AT. Learning scale free networks by reweighted l1 regularization. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2011. pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma S, Gong Q, Bohnert H. An arabidopsis gene network based on the graphical Gaussian model. Genome Research. 2007;17:1614–1625. doi: 10.1101/gr.6911207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mardia K, Kent J, Bibby J. Multivariate Analysis. Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazumder R, Hastie T. Exact covariance thresholding into connected components for large-scale graphical lasso. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2012;13:781–794. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meinshausen M, Buhlmann P. Stability selection (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2010;72:417–473. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meinshausen N, Bühlmann P. High dimensional graphs and variable selection with the lasso. Annals of Statistics. 2006;34:1436–1462. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milligan GW, Cooper MC. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika. 1985;50:159–179. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen AB, Perry PO. Bi-cross-validation of the SVD and the nonnegative matrix factorization. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2009;3(2):564–594. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng J, Wang P, Zhou N, Zhu J. Partial correlation estimation by joint sparse regression model. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;104(486):735–746. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2009.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravikumar P, Wainwright M, Raskutti G, Yu B. High-dimensional covariance estimation by minimizing ℓ1-penalized log-determinant divergence. Electronic Journal of Statistics. 2011;5:935–980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrígues-Concepción M, Boronat A. Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. a metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1079–1089. doi: 10.1104/pp.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman A, Bickel P, Levina E, Zhu J. Sparse permutation invariant covariance estimation. Electronic Journal of Statistics. 2008;2:494–515. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheinberg K, Ma S, Goldfarb D. Sparse inverse covariance selection via alternating linearization methods. NIPS 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shojaie A, Basu S, Michailidis G. Adaptive thresholding for reconstructing regulatory networks from time-course gene expression data. Statistics in Biosciences. 2012;4(1):66–83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tibshirani R, Walther G, Hastie T. Estimating the number of clusters in a dataset via the gap statistic. J Royal Statist Soc B. 2001;32:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wille A, Zimmermann P, Vranová E, Fürholz A, Laule O, Bleuler S, Hennig L, Prelíc A, Rohr P, Thiele L, Zitzler E, Gruissem W, Bühlmann P. Sparse graphical Gaussian modeling of the isoprenoid gene network in arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biology. 2004;5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witten D, Friedman J, Simon N. New insights and faster computations for the graphical lasso. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2011;20(4):892–900. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witten D, Tibshirani R, Hastie T. A penalized matrix decomposition, with applications to sparse principal components and canonical correlation analysis. Biostatistics. 2009;10(3):515–534. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wold S. Cross-validatory estimation of the number of components in factor and principal components models. Technometrics. 1978;20:397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue L, Zou H. Regularized rank-based estimation of high-dimensional nonparanormal graphical models. Annals of Statistics. 2012;40(5):2541–2571. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan M. Efficient computation of ℓ1 regularized estimates in Gaussian graphical models. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2008;17(4):809–826. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan M, Lin Y. Model selection and estimation in the Gaussian graphical model. Biometrika. 2007;94(10):19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou H. The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2006;101:1418–1429. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

be a set that contains p(p − 1)/2T elements of the form (i, j), where (i, j) is drawn randomly from {(i, j) : i, j ∈ {1, …, p}, i < j}. Augment the set

be a set that contains p(p − 1)/2T elements of the form (i, j), where (i, j) is drawn randomly from {(i, j) : i, j ∈ {1, …, p}, i < j}. Augment the set