Abstract

Since its original description in 2007, anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) encephalitis associated with an ovarian teratoma is an increasingly recognized etiology of previously unexplained encephalopathy and encephalitis. Extreme delta brush (EDB) is a novel electroencephalogram (EEG) finding seen in many patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. The presence of this pattern is associated with a more prolonged illness, although the specificity of this pattern is unclear. Additionally, the frequency and sensitivity of EDB in anti-NMDAR encephalitis and its implications for outcome have yet to be determined. We report a patient with early evidence of extreme delta brush and persistence of this pattern 17.5 weeks later with little clinical improvement.

Keywords: Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) encephalitis, Epilepsy, Extreme delta brush, Ovarian teratoma, Seizure

1. Introduction

Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) encephalitis is an increasingly recognized etiology of previously unexplained encephalopathy and encephalitis, since its original description in 2007 [1], [2]. The disease has initially been described in women with an ovarian teratoma but can also be seen in seen in women without an ovarian teratoma, men [3]. The syndrome usually develops with a sequential presentation of symptoms including headache and fever followed by behavioral changes, psychosis, catatonia, decreased level of consciousness, dyskinesias, and autonomic instability [4]. Seizures can occur at any stage but most commonly occur early [4]. Extreme delta brush (EDB) is a novel electroencephalogram (EEG) finding seen in 30.4% of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis [5]. The presence of this pattern is associated with a more prolonged illness, although the specificity of this pattern is unclear [5]. Additionally, the frequency and sensitivity of EDB in anti-NMDAR encephalitis, its implications for outcome, and whether there is a relationship between this pattern and antibody titers in serum and CSF have yet to be determined [5].

2. Case report

We report a 27-year-old woman with no significant past medical history who was brought to the emergency department after becoming “odder” at home one week after the funeral of her boyfriend. She had witnessed him violently shot to death ten days prior to the funeral. She was initially seen by a psychiatrist in the emergency department. Her family reported that she had not been sleeping or eating for a week, and she had been “rambling wildly” to herself ever since her boyfriend's funeral. She required chemical sedation in the emergency department as she became violent and hostile towards staff members. She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry ward for a presumed acute stress reaction with psychosis. She remained uncooperative and was exhibiting delusions that she had to leave because her boyfriend had survived the shooting and was actually waiting for her at home. Two days later, she was noted to have sialorrhea and was picking at her clothes and bed sheets. She subsequently had a witnessed 5-minute spontaneously resolving generalized tonic–clonic seizure. However, she was unresponsive after this seizure and would no longer verbalize or answer questions.

The neurology consultant observed that she had minimal responsiveness to voice, had intermittent picking movements at her bed sheets or clothing and was reaching for any instruments used to examine her [i.e., stethoscope or reflex hammer]. She also had a dysconjugate gaze when her eyelids were held open and was hyperreflexic throughout. She was afebrile and had no other abnormalities on her general physical exam.

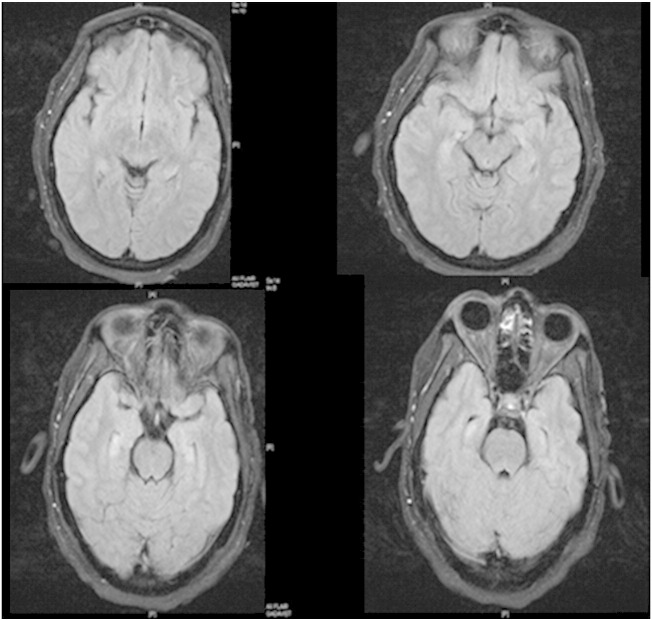

The initial electroencephalogram (EEG), performed 3 days after presentation, demonstrated frequent electrographic seizures arising independently from the right and left hemispheres. She was given intravenous (IV) lorazepam, started on intravenous fosphenytoin, and transferred to the neurological intensive care unit (ICU). A lumbar puncture was performed, showing 76 white blood cells/mm3 with a lymphocytic predominance (11 red blood cells/mm3, a protein level of 43 mg/dL, and a glucose level of 112 mg/dL). The CSF was sent for numerous studies including a full paraneoplastic panel, herpes simplex virus PCR, varicella zoster virus PCR, Epstein–Barr virus PCR, cytomegalovirus PCR, arbovirus panel, anti-NMDA receptor antibody titer, cytology, and flow cytometry. She was put on IV acyclovir while awaiting herpes simplex virus PCR results. Brain MRI with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images on 7/6/2013, 4 days after presentation, revealed abnormal high signal in the right medial temporal lobe. On repeat brain MRI imaging done two days later on 7/8/2013, she had hippocampal hyperintensity bilaterally on FLAIR images and enhancement after gadolinium contrast administration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Postcontrast FLAIR image from an MRI done on 07/8/2013, demonstrating bilateral hippocampal hyperintensity bilaterally, with enhancement after contrast administration.

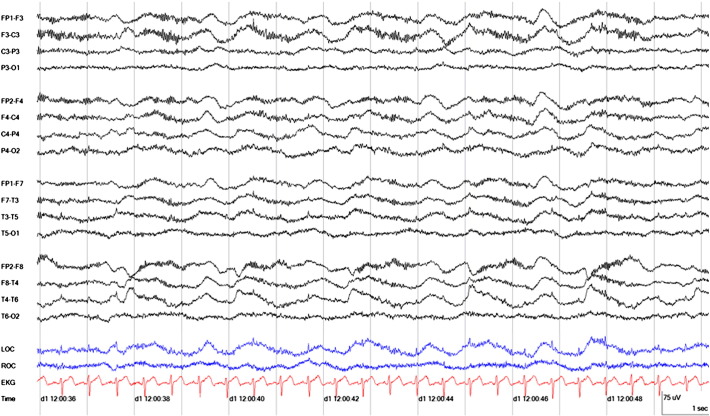

In the neurological ICU, the patient was noted to frequent peri-oral movements. She remained unresponsive. She continued to have frequent right temporal sharp waves on EEG. Levetiracetam and lacosamide were added on. Additionally, her continuous EEG monitoring within the first few days began to demonstrate frontally maximal high-voltage beta activity superimposed on frontally maximal delta waves (Fig. 2). This pattern of ‘extreme delta brush’ had been described as highly suggestive of anti-NMDAR encephalitis [5].

Fig. 2.

Early EEG demonstrates frontally maximal high-voltage beta activity superimposed on frontally maximal delta waves consistent with ‘extreme delta brush.’ There is also phase reversal on this bipolar montage over the right temporal lobe. This continuous EEG was captured on 7/07/2013 at 12:00 at a sensitivity of 5 μV/mm.

Given suspicion for an autoimmune-mediated process causing her symptoms, 1000 mg of methylprednisolone was started on 7/9/2013, 7 days after presentation. In addition, she was then started on plasmapheresis once the steroid course was completed. Unfortunately, she had minimal early clinical improvement. Her CSF result was positive for anti-NMDA receptor antibodies, and her diagnosis was therefore confirmed as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Numerous studies including CT torso, pelvic and vaginal ultrasound, pelvis MRI, and a PET scan either showed no evidence of malignancy or were limited by body habitus. A pelvic ultrasound was repeated given persistent elevated concern for an occult malignancy and revealed a right ovarian mass that was concerning for an underlying tumor. On 8/14/2013, 43 days after presentation, she underwent laparoscopic right salpingo-oophorectomy. Surgical pathology report was consistent with a mature cystic teratoma, which was ultimately believed to be the etiology of her immune-mediated encephalitis.

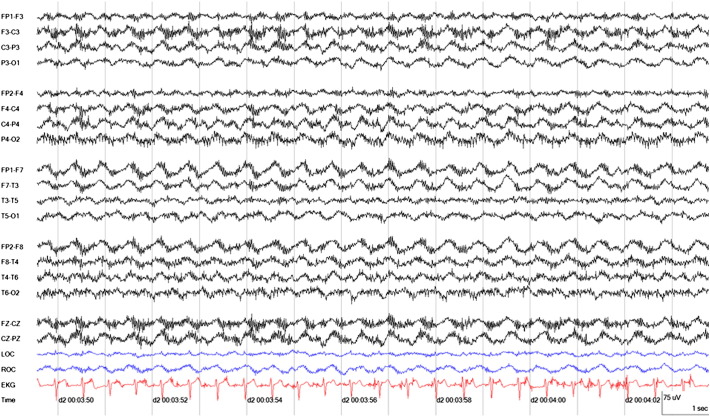

Unfortunately, there was no evident response to treatment. Despite completing 15 rounds of plasmapheresis, high-dose steroids, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and ketamine, her oral–facial and limb dyskinesias continued to be pronounced, and she continued to have large fluctuations in temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate. Her anti-NMDAR antibody remains positive (last tested on 11/11/2013, 132 days after presentation). Additionally, follow-up EEG performed on 10/31/2013, 121 days after presentation, continued to show pronounced extreme delta brush (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Late EEG demonstrates frontally maximal high-voltage beta activity superimposed on frontally maximal delta waves consistent with ‘extreme delta brush.’ This continuous EEG was captured on 10/21/2013 at 00:03 at a sensitivity of 5 μV/mm.

3. Discussion

We report a 17.5-week follow-up of a young woman with anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) encephalitis associated with an ovarian teratoma. The diagnosis was confirmed by persistence of a positive serum anti-NMDAR antibody and the continued presence of extreme delta brush (EDB) on continuous EEG. Extreme delta brush is a novel EEG finding seen in many patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis [5]. In this particular patient, the early finding facilitated an earlier diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Although specificity is uncertain, early diagnostic evaluation for malignancy should be pursued on the basis of clinical findings and EDB before the titers return. Because EDB is associated with a more prolonged illness, whether the persistence of this pattern has further implications for outcome is unclear [5]. Whether there is a relationship between this EDB pattern and antibody titers in serum and CSF has yet to be determined [5]. Additionally, whether there is a relationship between persistence of the anti-NMDAR antibody and continued EDB is also unclear. There are reported cases of the extreme delta brush pattern resolving [5]. However, the persistence of the finding has not been adequately correlated with outcomes or prognosis and requires further investigation.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Dalmau J., Tüzün E., Wu H., Masjuan J., Rossi J.E., Voloschin A. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.21050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prüss H., Dalmau J., Harms L., Höltje M., Ahnert-Hilger G., Borowski K. Retrospective analysis of NMDA receptor antibodies in encephalitis of unknown origin. Neurology. 2010;75(19):1735–1739. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc2a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florance N.R., Davis R.L., Lam C., Szperka C., Zhou L., Ahmad S. Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis in children and adolescents. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(1):11–18. doi: 10.1002/ana.21756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld M.R., Titulaer M.J., Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic syndromes and autoimmune encephalitis. Neurol Clin Pract. 2012:215–223. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e31826af23e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch L.J., Schmitt S.E., Friedman D., Pargeon K., Frechette E.S., Dalmau J. Extreme delta brush: a unique EEG pattern in adults with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology. 2012:1094–1100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182698cd8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]