Abstract

The extracellular matrix is increasingly recognized as an essential player in cancer development and progression. Collagens are one of the most important components of the extracellular matrix, and have themselves been implicated in many aspects of neoplastic transformation. Collagen XI is a minor collagen whose main physiologic function is to regulate the diameter of major collagen fibrils. The α1 chain of collagen XI (colXIα1), has known pathogenic roles in several musculoskeletal disorders. Recent research has highlighted the importance of colXIα1 in many types of cancer, including its roles in metastasis, angiogenesis, and drug resistance, as well as its potential utility in screening tests and as a therapeutic target. High levels of colXIα1 overexpression have been reported in multiple expression profile studies examining differences between cancerous and normal tissue, and between beginning and advanced stage cancer. Its expression has been linked to poor progression-free and overall survival. The consistency of this data across cancer types is particularly striking, including colorectal, ovarian, breast, head and neck, lung, and brain cancers. This review discusses the role of collagen XIα1 in cancer and its potential as a target for cancer therapy.

Keywords: Collagen, extracellular matrix, colXIα1, COL11A1, cancer

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is an essential component of the cancer cell niche. The ECM is a complex macromolecular network composed of biochemically distinct elements, including polysaccharides, proteoglycans, proteins, and glycoproteins. It provides structural support for cells in the form of the basement membrane, a specialized type of matrix essential for many cellular processes. In addition, the ECM forms the interstitial matrix, which is important in structural tissue support as well as in regulating and integrating cell behavior1,2.

The role of the ECM in tumor progression is becoming increasingly clear; a flood of recent research has illustrated that dysregulation of its various components plays an essential role in generating and maintaining the tumor microenvironment1,2. For example, tumor ECM is often stiffer and more highly crosslinked than normal stroma, promoting abnormal cell behavior3–5. Tumor cells are especially sensitive to changes in the stiffness of their environment, specifically increased collagen crosslinking, which then helps to drive the malignant phenotype3. A normal, functional ECM is essential for maintaining cellular architecture and polarity, which is universally lost in neoplastic growth. Abnormal ECM also promotes abnormal behavior in stromal cells, including the fibroblasts, immune cells, and endothelial cells that help make up the tumor microenvironment, and thus contributes to the formation and perpetuation of the neoplastic niche6,7.

One of the most important components of the ECM, and the most abundant protein in the body, is collagen. Currently there are 28 known collagens, which are trimeric molecules consisting of three polypeptide alpha chains (which may or may not be identical) forming a triple helix structure common to all collagens. The collagen family is diverse, and therefore is divided into three subgroups based on molecular structure and supramolecular assemblies: fibrillar collagens, non-fibril forming collagens, and fibril-associated collagens8–10. Fibrillar collagens are the most abundant, and are capable of forming highly ordered fibrils in the ECM. Fibril-associated collagens, containing interrupted triple helices, associate with and help regulate fibrillar collagens. Non-fibril forming collagens, which include type IV collagen found in the basement membrane, do not form or associate with fibrils8.

Many previous reports have revealed collagen XI as a player in human disease. Collagen XI is a minor fibrillar collagen most abundantly found in cartilage, but which has also been found in odontoblasts, trabecular bone, skeletal muscle, placenta, lung, and neoepithelium of the brain11. Collagen XI copolymerizes with both collagen II and collagen IX, and is essential in maintaining proper fibril diameter and function in connective tissue; absence or mutation in the alpha chain of collagen XI results in abnormally thickened cartilage fibrils12. Collagen XI, like all collagens, is a heterotrimer consisting of α1, α2, and α3 chains, located on different chromosomes, which are synthesized as procollagens and proteolytically cleaved to yield mature trimers11. The α1 and α2 chains are genetically distinct, while the α3 chain is a hyperglycosylated form of the α1 chain of collagen II. Mutations in the gene encoding the α1 chain of collagen XI (colXIα1) have been implicated in many musculoskeletal disorders, including Stickler syndrome, characterized by opthalamic, articular, orofacial, and auditory abnormalities13,14; fibrochondrogenesis, a lethal form of dwarfism15; as well as osteoarthritis16, lumbar disc herniation17, limbus vertebra18, and Achilles tendinopathy19.

Recent progress has highlighted an important role for collagen XI in many aspects of neoplastic transformation. This review will focus on the role of collagen XIα1 in cancer.

Dysregulation of collagen XIα1 in cancer

Normal, physiologic expression of collagen XI is very low or nonexistent in most tissues20–22. Therefore, changes in collagen XIα1 (colXIα1) expression associated with cancer are excellent putative markers both of neoplastic change and disease progression.

ColXIα1 was found to be the most highly overexpressed gene in high-stage (versus low-stage) cancer in a meta-analysis of microarray data from multiple cancers23. This analysis generated a metastasis-associated gene expression signature of which colXIα1 was the top hit, and which was common to multiple cancers, including ovarian, colon, breast, and lung23. This metastasis-associated gene expression signature corresponds to a stromal desmoplastic reaction commonly produced by tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs). This reaction is frequently present in high stage cancers either in the process of or which have already invaded into the surrounding tissues and/or metastasized to distant sites. Specifically, colXIα1 mRNA expression correlated with cancer staging in this group of cancers, suggesting that it alone can be used as a proxy for the metastasis-associated gene expression signature. Expression of this metastasis-associated gene signature by primary tumors may be an early marker for invasive potential23,24. To validate this data, human neuroblastoma cells were xenografted into immunocompromised mice. The resulting tumors also expressed high levels of colXIα1 as assessed by quantitative PCR, as well as the other epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-associated genes in the signature24. This signature was only expressed by the xenografted human cells, and not the surrounding mouse stroma, suggesting that signals for EMT derive specifically from the tumor24. A subset of murine adipocyte markers was downregulated in association with the upregulation of EMT signature genes, implicating adipocytes in the development of cancer cell invasion. Similarly, highly migratory human glioma cells were used to assess markers for cell invasion and their epigenetic controls, as compared to non-migratory breast cancer cells. ColXIα1 mRNA was highly upregulated in the glioma cells as compared to the breast cancer cells. This was associated with both hyperacetylation and methylation of specific lysine residues on histone 3, both of which are markers for transcriptional activation25. ColXIα1 is also highly expressed at the protein level in human gliomas versus paired normal tissue26.

Colorectal carcinoma

The role of colXIα1 in cancer was first identified in sporadic colorectal cancer, which expresses high levels of colXIα1 mRNA, while there is no expression in normal colonic tissue. In this setting, colXIα1 seems to be co-expressed with collagen Vα2, the other minor fibrillar collagen with which collagen XI shares a high degree of sequence homology, and which is also not expressed in normal adult colon20. ColXIα1 is also overexpressed in colon polyps from patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, an inherited mutation in the tumor suppressor APC which causes colorectal carcinoma. The authors suggest that colXIα1 overexpression could be related to the APC/β-catenin pathway, which is dysregulated not only in familial adenomatous polyposis but also in the majority of sporadic colorectal cancers21. This aberrant expression has been linked to a mutation in exon 54 in the colXIα1 gene, discovered by analyzing mutations in exfoliated tumor cells from the stool of colorectal cancer patients. The mutation may act as a potential non-invasive screening test for colorectal cancer27.

Ovarian carcinoma

In a study looking at gene expression in human epithelial ovarian cancer tissue samples, colXIα1 was the most highly expressed of the studied genes, and expression correlated with stage of disease28. High colXIα1 at both the mRNA and protein level was also associated with cancer recurrence or persistence, as well as lower overall and disease-free survival28,29. ColXIα1 was similarly identified as part of a 10-gene panel from 403 high-grade serous ovarian cancer samples predictive of poor clinical outcome30. Furthermore, colXIα1 expression (both mRNA and protein) differs by tumor site and stage: the lowest levels were expressed in primary ovarian cancer samples, moderate levels in concurrent metastases, and highest levels in recurrent/persistent metastases from the same patient30. ColXIα1 was also the most highly overexpressed gene in a microarray study of metastatic versus primary ovarian serous papillary carcinoma, where it was upregulated by an average of 8.23-fold in omental metastases31. ColXIα1 was identified as one of 12 genes highly expressed in ovarian tumor vasculature, and may serve as a tumor biomarker32. Markers of tumor blood supply may act as important drug targets, following in the footsteps of the VEGF inhibitor bevacizumab, which has been successful as part of a multi-therapy regimen in treating many types of solid tumors.

Breast carcinoma

Multiple studies have found that colXIα1 is much more highly expressed in invasive ductal carcinoma than its precursor, the premalignant lesion ductal carcinoma in situ, indicating that it may play a role in local invasion of cancer cells33–35. Additionally, increased colXIα1 expression has been reported in primary breast tumors compared to paired lymph node metastases36,37. Overexpression of colXIα1, along with other similar extracellular matrix genes, at primary tumor sites suggests that it is important in modulating the ECM to facilitate tumor cell dissemination and therefore metastasis; this is in agreement with the findings from the metastasis-associated gene signature discussed above. ColXIα1 was also overexpressed in a “high risk” group of breast cancer patients, who were axillary lymph node-positive and had distant metastases within follow up time (43 months), versus those in the “low risk” group, who were also node-positive but had no metastases within this time36. However, another study found that colXIα1 protein was actually downregulated in primary breast tumors that had metastasized versus those that had not38. The apparent discrepancy may be due to the use of immunohistochemistry to assess protein level, versus the study describing higher expression in primary tumors, which was based on mRNA data.

Aerodigestive tract tumors

Similar to the above findings, in a microarray study of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), colXIα1 was one of two genes of 12,000 studied found to be highly upregulated (by an average of 476-fold) in all HNSCC samples studied, and had no expression in normal tissue, making it an ideal marker for HNSCC39. This finding was confirmed by another study in which colXIα1 was upregulated by an average of 6.63 fold in HNSCC tumors versus normal adjacent tissue40. An additional study demonstrated a 7.5-fold increase in colXI α1 mRNA levels in metastatic HNSCC tumors compared to non-metastatic tumors41. A genome-wide analysis examining chromosomal alterations occurring in environmental insult-initiated esophageal squamous cell carcinoma found significant amplification of colXIα1 gene compared to matched normal tissue, which may be used as an early biomarker for esophageal cancer42. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the colXIα1 gene have been linked to papillary thyroid cancer, with certain alleles conferring a protective effect43.

ColXIα1 is also overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer, as well as correlating with pathological stage, presence of lymph node metastasis, and poor prognosis44. In transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, colXIα1 is one of seven genes with differential expression between superficial and muscle-invasive tumors45. ColXIα1 expression is also capable of differentiating premalignant from malignant stomach cancers46. See Table 1 for a summary of colXIα1 dysregulation across cancer types.

Table 1.

Dysregulation of colXIα1 in cancer.

| Cancer type | Sample type | Dysregulation | Control | Clinical association | Measurement level | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | muscle-invasive transitional cell carcinoma | Overexpressed | papillary transitional cell carcinoma tissue | muscle invasion | mRNA | 45 |

| Breast | IDC | Underexpressed | nonmetastasized primary tumor | metastasis | protein | 38 |

| Breast | tumor stroma | Underexpressed | normal stroma | tumor stroma | protein | 38 |

| Breast | IDC | Overexpressed | DCIS, normal breast tissue, mouse breast carcinomas | local invasion | mRNA | 34 |

| Breast | IDC | Overexpressed | paired lymph node metastases | primary tumor; high risk of metastasis | mRNA | 36 |

| Breast | IDC | Overexpressed | DCIS and normal adjacent stroma | local invasion | mRNA | 33 |

| Breast | Multiple breast cancer types | Overexpressed | normal breast tissue | tumor-associated fibroblasts | Protein | 49 |

| Colorectal | sloughed tumor cells | Mutation | none | malignancy | DNA | 27 |

| Colorectal (inherited) | FAP polyps | Overexpressed | paired normal colon tissue | malignancy | mRNA | 21 |

| Colorectal (sporadic) | multiple CRC types | Overexpressed | Normal colon tissue | malignancy | mRNA | 20 |

| Gastric | tumor resection margins | Overexpressed | gastric tumor and normal gastric tissue | resection margin | protein | 50 |

| Gastric | multiple gastric cancer types | Overexpressed | paired premalignant and normal gastric tissue | malignancy | mRNA | 46 |

| Glioma | gliobastoma | Overexpressed | paired normal neural tissue | malignancy | mRNA, protein | 26 |

| Glioma | tumor cells | Overexpressed | non-migratory tumor cells | motility | mRNA | 25 |

| HNSCC | HNSCC, multiple sites | Overexpressed | paired normal mucosal tissue | malignancy | mRNA | 39 |

| HNSCC | HNSCC, multiple sites | Overexpressed | paired normal mucosal tissue | malignancy, metastasis | mRNA | 40 |

| HNSCC | oral cavity/oropharynx SCC | Overexpressed | nonmetastatic HNSCC, normal mucosa | metastasis | mRNA | 41 |

| HNSCC | esophageal SCC | DNA amplification | paired normal tissue | malignancy | DNA | 42 |

| Lung | NSCLC | Overexpressed | normal lung tissue | pathological stage; lymph node metastasis, poor prognosis | mRNA | 44 |

| Ovarian | epithelial ovarian cancer | Overexpressed | internal | pathological stage; lower overall survival, lower progression-free survival | mRNA | 28 |

| Ovarian | serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer | Overexpressed | internal | poor prognosis | mRNA | 31 |

| Ovarian | tumor cells | Overexpressed | non-resistant cell lines | drug resistance | protein | 29 |

| Ovarian | serous ovarian cancer | Overexpressed | internal | metastasis; lower overall survival | mRNA, protein | 30 |

| Ovarian | epithelial ovarian cancer vasculature | Overexpressed | healthy ovarian vascular tissue | angiogenesis | mRNA, protein | 32 |

| Pancreatic | PDAC | Overexpressed | chronic pancreatitis and normal pancreas tissue | tumor-associated fibroblasts | mRNA, protein | 47 |

| Thyroid | peripheral blood | SNP | peripheral blood from healthy subjects | increased/reduced cancer risk | DNA | 43 |

ColXIα1 and tumor-associated stroma

TAFs are the most abundant cell type within the stroma of many solid malignancies. ColXIα1 was found to be more highly expressed by TAFs isolated from HNSCC explants than in normal fibroblasts derived from cancer-free patients40. Immunohistochemical studies in pancreatic cancer have also suggested that colXIα1 may be a marker capable of differentiating TAFs from normal activated fibroblasts, a distinction which has been elusive so far47. In ovarian cancer studies, colXIα1 expression was mainly confined to stromal cells, specifically to the intra/peritumoral stromal cells, and not expressed >1 mm from epithelial tumor cells, indicating again that colXIα1 is a specific marker for TAFs, and potentially for malignant cells undergoing EMT30. Taken together, this strongly implicates stroma-secreted colXIα1 in the ECM modulation that is critical in facilitating tumor spread.

ColXIα1 is highly expressed in the stroma of breast cancer, with anti-procolXIα1 antibodies capable of recognizing invasive ductal carcinoma-associated TAFs and therefore differentiating breast malignancies from benign lesions, which have very little or no procolXIα1 expression48,49. Similarly, resection margins from gastric carcinoma patients exhibit high colXIα1 levels50. Expression is also limited to stroma in colorectal cancer20. However, in several of the studies discussed above, the source of increased colXIα1 was the epithelial compartment, not the surrounding stroma, suggesting a complex interplay between these two factors in facilitating tumor invasion.

ColXIα1 as a therapeutic target

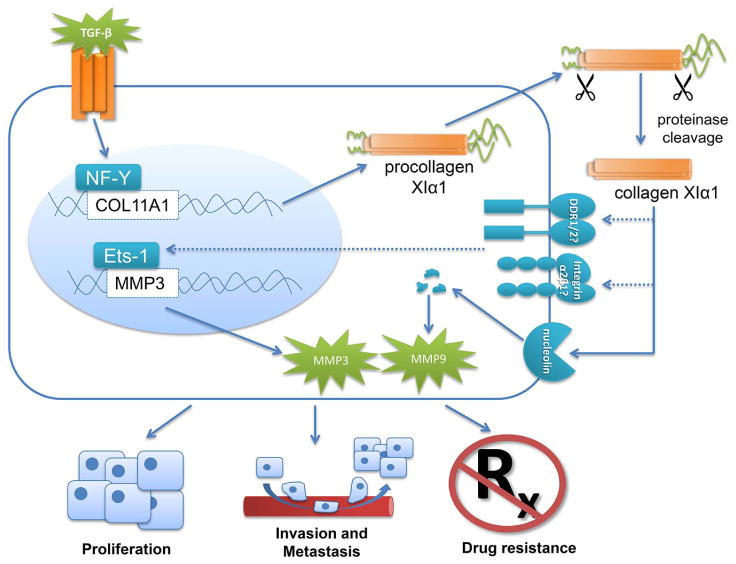

Although colXIα1 is clearly active in promoting cancer progression and metastasis, descriptive studies, even with human tissue, are limited in terms of functional or mechanistic significance. Thus it is noteworthy that functional studies in various cancer types have confirmed that dysregulation of colXIα1 expression is indeed playing a relevant role in neoplastic progression (Figure 1). ColXIα1 siRNA-mediated knockdown in both ovarian cancer cell lines and HNSCC cell lines significantly suppressed invasion and slowed proliferation. This effect was not observed when normal, non-cancerous cells were transfected with colXIα1 siRNA, further confirming its potential as a therapeutic target28,40. In the ovarian cancer cell lines, colXIα1 knockdown was associated with decreased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 3 mRNA expression and activity. This effect was mediated through Ets-1, a transcription factor that regulates expression of many matrix-modulating genes, including several MMPs, and which is known to be expressed in many types of cancer. ColXIα1 knockdown decreased Ets-1 binding to the MMP3 promoter, indicating that the effect of colXIα1 on cell invasion may be mediated through MMP3 upregulation28. When colXIα1-knockdown cells were inoculated into mice, they showed impaired tumor spread and invasion compared to mice injected with cells expressing wild-type colXIα128,30. One study in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer suggests that colXIα1 may be a downstream target of the Hedgehog signaling pathway, which is activated in most pancreatic cancers. In pancreatic cancer cells, overexpression of Gli1, the major transcription factor activated by the Hedgehog pathway, resulted in increased expression of colXIα151. Studies in pancreatic and ovarian cancer have also suggested that colXIα1 is a downstream target of the TGF-β signaling pathway, which is itself regulated by the ECM and is commonly dysregulated in cancer. TGF-β upregulates colXIα1 expression through transcription factor NF-Y28,30,52. Treatment with TGF-β inhibitors drastically reduced colXIα1 expression in ovarian cancer cell lines, as well as cell invasion28.

Figure 1.

Collagen XIα1 in cancer promotion. ColXIα1 is a downstream target of the TGF-β pathway, acting through transcription factor NF-Y. Once translated, procolXIα1 is transported into the ECM, where its N and C termini are cleaved by proteinases. Mature colXIα1 can then regulate MMP3 expression through transcription factor Ets-1, perhaps through putative cell surface receptors integrin α2β1 and/or DDR1/2. ColXIα1 also binds nucleolin, a cell surface receptor, which autolytically degrades itself into fragments which post-transcriptionally regulate MMP9. Ultimately, colXIα1 promotes cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, and therapeutic resistance.

ColXIα1 has also been linked with therapeutic resistance, which is a significant problem across cancer types. The stroma is often hypothesized as the source of resistance to many targeted therapies that seem promising in vitro but fail in clinical trials. The colXIα1-driven metastasis-associated gene expression signature discussed above was also associated with resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer23. High levels of colXIα1 protein secretion have been linked with resistance to platinum-based therapies in ovarian cancer29. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting collagen XI may help sensitize cells to conventional treatments.

Precisely how colXIα1 is mediating these effects is unknown. Limited research has identified integrin α2β1 and the discoidin domain receptor family as putative collagen XI receptors; however, very little is known about downstream signaling53,54. One potential colXIα1 binding partner is nucleolin, a nuclear transport protein which also has autolytic activity. This activity results in cleavage products capable of post-transcriptionally regulating MMP9, which, like MMP3, may be involved in colXIα1-mediated cell invasion55. Overall, development of approaches to target colXIα1 would be therapeutically beneficial. Approaches including antisense targeting or modulation of transcription or translation for colXIα1 may hold the most promise.

Conclusion

The expression pattern of colXIα1 in cancer is obviously complex and incompletely understood. While most studies point to a direct relationship between colXIα1 expression and cancer progression, specifically as it pertains to metastasis, there are some seemingly discordant findings. The expression of colXIα1 changes as the tumor evolves, and differences in study timepoints and the source of the colXIα1, whether it be the tumor itself or the surrounding stroma, may account for large expression differences. A limited number of functional studies confirm that colXIα1 is playing a role in cancer proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, as well as in resistance to therapeutics. More in-depth studies are needed to determine mechanisms through which colXIα1 influences cancer cell behavior. What data is available suggests that collagen XIα1, with its low expression in normal tissue and high expression in cancer, and its mechanistic significance, may be an ideal target for future therapies across multiple cancer types.

Highlights.

Collagen XI is a minor collagen with pathogenic roles in musculoskeletal diseases

ColXIα1 is overexpressed at mRNA and protein levels in many cancer types

ColXIα1 is highly expressed in tumor stroma, especially by tumor-associated fibroblasts

ColXIα1 has functional roles in cancer development and may be a therapeutic target

Acknowledgments

Department of Otolaryngology, University of Kansas Medical Center and University of Kansas Cancer Center’s CCSG (1-P30-CA168524-02) were the funding sources. ZR was supported by the University of Kansas Cancer Center Summer Student Training Grant.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barkan D, Green JE, Chambers AF. Extracellular matrix: a gatekeeper in the transition from dormancy to metastatic growth. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes RO. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 2009;326:1216–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, et al. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J. 2000;79:144–52. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter EM, Raggio CL. Genetic and orthopedic aspects of collagen disorders. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:46–54. doi: 10.1097/mop.0b013e32832185c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grassel S, Bauer RJ. Collagen XVI in health and disease. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricard-Blum S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004978. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshioka H, Iyama K, Inoguchi K, et al. Developmental pattern of expression of the mouse alpha 1 (XI) collagen gene (Col11a1) Dev Dyn. 1995;204:41–7. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hida M, Hamanaka R, Okamoto O, et al. Nuclear factor Y (NF-Y) regulates the proximal promoter activity of the mouse collagen alpha1(XI) gene (Col11a1) in chondrocytes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2014;50:358–66. doi: 10.1007/s11626-013-9692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domet MJ. The general pediatrician and the craniofacial defects team. Ear Nose Throat J. 1986;65:296–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijzelaar R, Waller S, Errami A, et al. Deletions within COL11A1 in Type 2 stickler syndrome detected by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekdache GN, Begam MA, Chedid F, et al. Fibrochondrogenesis: prenatal diagnosis and outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:663–8. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.817977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Fontenla C, Calaza M, Evangelou E, et al. Assessment of osteoarthritis candidate genes in a meta-analysis of nine genome-wide association studies. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:940–9. doi: 10.1002/art.38300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mio F, Chiba K, Hirose Y, et al. A functional polymorphism in COL11A1, which encodes the alpha 1 chain of type XI collagen, is associated with susceptibility to lumbar disc herniation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1271–7. doi: 10.1086/522377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koyama K, Nakazato K, Min S, et al. COL11A1 gene is associated with limbus vertebra in gymnasts. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:586–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hay M, Patricios J, Collins R, et al. Association of type XI collagen genes with chronic Achilles tendinopathy in independent populations from South Africa and Australia. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:569–74. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer H, Stenling R, Rubio C, et al. Colorectal carcinogenesis is associated with stromal expression of COL11A1 and COL5A2. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:875–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer H, Salahshor S, Stenling R, et al. COL11A1 in FAP polyps and in sporadic colorectal tumors. BMC Cancer. 2001;1:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imamura Y, Scott IC, Greenspan DS. The pro-alpha3(V) collagen chain. Complete primary structure, expression domains in adult and developing tissues, and comparison to the structures and expression domains of the other types V and XI procollagen chains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8749–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Watkinson J, Varadan V, et al. Multi-cancer computational analysis reveals invasion-associated variant of desmoplastic reaction involving INHBA, THBS2 and COL11A1. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:51. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anastassiou D, Rumjantseva V, Cheng W, et al. Human cancer cells express Slug-based epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene expression signature obtained in vivo. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:529. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chernov AV, Baranovskaya S, Golubkov VS, et al. Microarray-based transcriptional and epigenetic profiling of matrix metalloproteinases, collagens, and related genes in cancer. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19647–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An JH, Lee SY, Jeon JY, et al. Identification of gliotropic factors that induce human stem cell migration to malignant tumor. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:2873–81. doi: 10.1021/pr900020q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suceveanu AI, Suceveanu A, Voinea F, et al. Introduction of cytogenetic tests in colorectal cancer screening. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu YH, Chang TH, Huang YF, et al. COL11A1 promotes tumor progression and predicts poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng PN, Wang G, Hood BL, et al. Identification of candidate circulating cisplatin-resistant biomarkers from epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell secretomes. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:123–32. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheon DJ, Tong Y, Sim MS, et al. A collagen-remodeling gene signature regulated by TGF-beta signaling is associated with metastasis and poor survival in serous ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:711–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tothill RW, Tinker AV, George J, et al. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5198–208. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buckanovich RJ, Sasaroli D, O’Brien-Jenkins A, et al. Tumor vascular proteins as biomarkers in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:852–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas AC, McCart Reed AE, Waddell N, et al. Gene expression profiling of tumour epithelial and stromal compartments during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:153–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castellana B, Escuin D, Peiro G, et al. ASPN and GJB2 Are Implicated in the Mechanisms of Invasion of Ductal Breast Carcinomas. J Cancer. 2012;3:175–83. doi: 10.7150/jca.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knudsen ES, Ertel A, Davicioni E, et al. Progression of ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer is associated with gene expression programs of EMT and myoepithelia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:1009–24. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1894-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng Y, Sun B, Li X, et al. Differentially expressed genes between primary cancer and paired lymph node metastases predict clinical outcome of node-positive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:319–29. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellsworth RE, Seebach J, Field LA, et al. A gene expression signature that defines breast cancer metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26:205–13. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halsted KC, Bowen KB, Bond L, et al. Collagen alpha1(XI) in normal and malignant breast tissue. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1246–54. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sok JC, Kuriakose MA, Mahajan VB, et al. Tissue-specific gene expression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vivo by complementary DNA microarray analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:760–70. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.7.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sok JC, Lee JA, Dasari S, et al. Collagen type XI alpha1 facilitates head and neck squamous cell cancer growth and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:3049–56. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmalbach CE, Chepeha DB, Giordano TJ, et al. Molecular profiling and the identification of genes associated with metastatic oral cavity/pharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:295–302. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chattopadhyay I, Singh A, Phukan R, et al. Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal alterations in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma exposed to tobacco and betel quid from high-risk area in India. Mutat Res. 2010;696:130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park HJ, Choe BK, Kim SK, et al. Association between collagen type XI alpha1 gene polymorphisms and papillary thyroid cancer in a Korean population. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2:1111–1116. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chong IW, Chang MY, Chang HC, et al. Great potential of a panel of multiple hMTH1, SPD, ITGA11 and COL11A1 markers for diagnosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2006;16:981–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewald JA, Downs TM, Cetnar JP, et al. Expression microarray meta-analysis identifies genes associated with Ras/MAPK and related pathways in progression of muscle-invasive bladder transition cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y, Zhou T, Li A, et al. A potential role of collagens expression in distinguishing between premalignant and malignant lesions in stomach. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292:692–700. doi: 10.1002/ar.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Pravia C, Galvan JA, Gutierrez-Corral N, et al. Overexpression of COL11A1 by cancer-associated fibroblasts: clinical relevance of a stromal marker in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuentes-Martinez N, Garcia-Pravia C, Garcia-Ocana M, et al. Overexpression of proCOL11A1 as a stromal marker of breast cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2014 doi: 10.14670/HH-30.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García Pravia CFMN, García Ocaña M, Del Amo J, De los Toyos JR, et al. Anti-proCOL11A1, a new marker of infiltrating breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;S5:11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aquino PF, Fischer JS, Neves-Ferreira AG, et al. Are gastric cancer resection margin proteomic profiles more similar to those from controls or tumors? J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5836–42. doi: 10.1021/pr300612x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feldmann G, Habbe N, Dhara S, et al. Hedgehog inhibition prolongs survival in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2008;57:1420–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.148189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaspar NJ, Li L, Kapoun AM, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta signaling reduces pancreatic adenocarcinoma growth and invasiveness. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:152–61. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuckwell DS, Reid KB, Barnes MJ, et al. The A-domain of integrin alpha 2 binds specifically to a range of collagens but is not a general receptor for the collagenous motif. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:732–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shrivastava A, Radziejewski C, Campbell E, et al. An orphan receptor tyrosine kinase family whose members serve as nonintegrin collagen receptors. Mol Cell. 1997;1:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown RJ, Mallory C, McDougal OM, et al. Proteomic analysis of Col11a1-associated protein complexes. Proteomics. 2011;11:4660–76. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]