Abstract

Objective

Living with food allergy is a unique and potentially life-threatening stressor that requires constant vigilance to food-related stimuli, but little is known about whether adolescents with food allergies are at increased risk for psychopathology—concurrently and over time.

Methods

Data came from the prospective-longitudinal Great Smoky Mountains Study. Adolescents (N = 1,420) were recruited from the community, and interviewed up to six times between ages 10 to 16 for the purpose of the present analyses. At each assessment, adolescents and one parent were interviewed using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment, resulting in N = 5,165 pairs of interviews.

Results

Cross-sectionally, food allergies were associated with more symptoms of separation and generalized anxiety, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and anorexia nervosa. Longitudinally, adolescents with food allergy experienced increases in symptoms of generalized anxiety and depression from one assessment to the next. Food allergies were not, however, associated with a higher likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder.

Conclusion

The unique constellation of adolescents’ increased symptoms of psychopathology in the context of food allergy likely reflects an adaptive increase in vigilance rather than cohesive syndromes of psychopathology. Support and guidance from health care providers is needed to help adolescents with food allergies and their caregivers achieve an optimal balance between necessary vigilance and hypervigilance and unnecessary restriction.

Keywords: adolescence, psychopathology, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, food allergy, stressors

Food allergies are increasingly prevalent and pose a significant public health burden (1, 2). Prevalence estimates range from 2 to 8% (3), and vary within that range depending on the food allergen(s) assessed, the methodology used, and the region and historical period studied (4, 5). A recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study, using specific serum IgE levels as an indicator, estimated the prevalence of clinical food allergies to four common allergens (peanut, milk, egg, shrimp) at about 2.5% in the US population, with higher rates in 1-5 year-olds (4.2%) and 6-19 year-olds (3.8%) than among older age groups (6).

Living with food allergies constitutes a unique stressor: Daily meals and snacks can trigger a rapidly-progressing, life-threatening allergic reaction. This stressor is both chronic and acute: For years, youth face the daily threat of accidental allergen ingestion compounded by acute stress during allergy-related health crises (7). Strict allergen avoidance is the best known strategy to manage food allergies (8). Consequently, successful management requires careful attention to external food-related cues, such as being offered food, and internal, somatic cues associated with food-induced allergic reactions, including skin, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and cardiovascular symptoms. Despite the significant number of US families affected by stressors experienced in the course of this chronic illness, and the constant vigilance to food-related stimuli that is required, relatively little research has focused on the psychological sequelae of living with food allergies. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of 340 studies that tested associations between chronic physical illness and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents did not include data on food allergies (9).

One extant line of research has examined how quality of life is impacted by food allergies, with a recent review (7) indicating that youth with food allergies reported lower health-related quality of life, more physical symptoms, and higher scores on select anxiety inventories (10-13). Specific fears reported included separation anxiety, fear of adverse events, and anxiety about eating (14, 15). The majority of this work, however, was based on relatively small samples that were recruited in specialty clinics and hospitals, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. To our knowledge, only one study has examined linkages between food allergies and a range of psychiatric diagnoses in a larger-scale community-based study (16). Using the Canadian Community Health Study with participants aged 15 and older, it found that self-reported food allergies were associated with an increased 12-month prevalence of several mood and anxiety disorders (major depression, panic disorder/agoraphobia, bipolar disorder). This study was cross-sectional, however, and, while informative, did not address the longitudinal impact of food allergy on psychopathology.

The present study examined cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between food allergy and psychopathology symptoms and diagnoses and extended extant research in several ways. First, we used a community-based epidemiological sample of adolescents. Adolescents in this study were recruited from the community; thus generalizability of findings will not be limited to care-seeking clinic-based samples. Second, we expanded the range of psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses examined to include disruptive and eating disorders. The extension to eating disorders is important considering the constant food-related vigilance required in the context of food allergies. The extension to behavioral disorders is important, because this group of disorders tends to be comorbid with internalizing disorders (17), and also often precedes later internalizing disorders (18). Third, in order to better understand whether—given the unique stressor that they encounter—adolescents with food allergies present a specific pattern of psychopathology symptoms, we conducted a symptom-by-symptom analysis. Fourth, we tested whether associations between food allergies and psychopathology differed by sex. Sex differences have been suggested by other work on atopy/allergy, but are only rarely tested in work on food allergy (19). Finally, in order to rule out alternative explanations, we adjusted for the presence of other atopic conditions and medication use when testing associations between food allergies and psychopathology. We focused on ages 10 to 16, an age-range at which responsibility for the management of food allergies is increasingly transferred from caregivers to their children, and toward the end of which risk for serious anaphylactic reactions peaks (20).

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The Great Smoky Mountains Study (GSMS) is a longitudinal study of the development of psychiatric disorder in rural and urban youth. The accelerated cohort, two-phase sampling design and measures are described in detail elsewhere (21, 22). Briefly, a representative sample of three cohorts of children, aged 9, 11, and 13 years at intake was recruited from 11 counties in western North Carolina. Potential participants were selected from the population of about 12,000 eligible children using a household equal probability, accelerated cohort design. All children scoring above a predetermined cutpoint (the top 25% of the total scores) on a behavioral problems screening questionnaire (23), plus a 1 in 10 random sample of the rest (i.e., the remaining 75%) were recruited for detailed interviews. Importantly, in all statistical analyses, participants were assigned a weight inversely proportional to their probability of selection into the sample. Thus, results are representative of the population from which the sample was drawn, and results are not biased from the oversampling procedure. Of all children recruited, 80% (N = 1,420) agreed to participate.

About 8% of the area residents and the sample are African American; less than 1% are Hispanic. American Indians constituted only about 3% of the population of the study area, but, because they are an understudied group, they were oversampled to constitute 25% of the study sample. This oversampling strategy has provided a sufficient sample of American Indian children for computing epidemiological estimates and testing risk pathways for this understudied group using the GSMS. However, race/ethnic differences are not a primary focus of the present paper. Therefore, and, as explained above, oversampling of the American Indian group was adjusted for in the analyses by using sampling weights in the current analyses. Thus, the results reported here are not biased from the oversampling procedure. Participants were assessed annually to age 16. Across waves/assessments, participation rates ranged between 74-94%. The parent (typically the mother) and child were interviewed separately by trained interviewers. Before the interviews began, parent and child signed informed consent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Each parent and child received a small honorarium for their participation.

Measures

Food allergies were assessed from parents beginning at Wave/Assessment 2, using a physical health problems survey adapted from the CDC National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Child Supplement (1988). The questions asked were: “Has s/he ever had any kind of food or digestive allergy? Has s/he had it in the last 12 months?” The parent reported in a binary “yes/no” format whether the child had “any kind of food or digestive allergy” in the past year. In the present analyses, a binary variable coded whether food or digestive allergies were present in the past year.

Psychiatric symptoms and disorders were measured at the same assessment as food allergies, using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA), a structured interview (24). Two-week test-retest reliability of diagnoses assessed with the CAPA is comparable to that of other highly-structured child psychiatric interviews (25); construct validity is good to excellent (24). The time frame for ascertaining the presence of most symptoms was the past three months to minimize forgetting and recall biases. A symptom was counted as present if reported by either parent or child, as is standard clinical practice (with the exception of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), for which only the more reliable parent report was used).

Symptoms for any given diagnosis were aggregated into two variables. First, we summed symptoms for each diagnosis, creating continuous scales of symptoms (e.g., a scale with a possible range of 0-8 for separation anxiety symptoms). Second, we created dichotomous diagnostic variables. Scoring programs written in SAS combined information about the date of onset, duration, and intensity of each symptom to create diagnoses according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (26). We also computed one non-overlapping total symptoms score summing all psychopathology symptoms, and one binary variable indicating whether criteria for any DSM-IV disorder had been met. We focused on relatively common anxiety disorders of childhood (generalized anxiety, separation anxiety), depressive disorders (major depression, dysthymia, depressive disorder not otherwise specified), conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD, and anorexia and bulimia nervosa. All symptoms assessed can be viewed at: http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/codebooks.html (with the exception of anorexia and bulimia nervosa). Symptoms for anorexia and bulimia nervosa were assessed in a manner consistent with DSM-IV criteria and included underweight status for age and height; cognitive symptoms such as fear of gaining weight and body image disturbance, including unrealistic feelings of fatness; amenorrhea in post-menarcheal females; eating binges; and unhealthy weight control behaviors that had the specific intent to reduce body weight.

Alternative explanatory variables included the presence of other atopic diseases (asthma, respiratory allergies, hayfever, eczema), which was also assessed using the adapted CDC NHIS Form (1988). A summary variable counted how many additional atopic conditions were reported for each adolescent. Medication use during the prior year was assessed with the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (27). A binary variable coded the use of any medication in the past year. Low socioeconomic status (SES) was positive if the child’s family met two or more of the following conditions: below the federal poverty line for family income, parental high school education only, or low parental occupational prestige. Parental depression was positive if the parent had 9+ symptoms on the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold, Costello, Messer, Pickles, Winder, & Silver, 1995).

Analyses

Cross-sectional analyses

Altogether, 5,231 interviews with adolescents aged 10-16 years and their parents took place, and 5,165 had complete data on the food allergy variable. Models predicting psychopathology symptoms scales employed Poisson regression. Models predicting psychopathology diagnoses employed logistic regression. These weighted regression models were implemented in a generalized estimating equations framework using SAS PROC GENMOD, specifying the covariance matrix as exchangeable. In the cross-sectional analyses, multiple observations from an individual were treated as independent observations, with robust (sandwich type) variance estimates adjusting the standard errors of the parameter estimates for repeated observations and design effects. Thus, the cross-sectional analyses accounted for the repeated measures from the same individuals.

Longitudinal analyses used lagged food allergy and psychopathology variables (i.e., food allergy and psychopathology at the prior assessment) to predict current psychopathology. For example, in the model testing increases in generalized anxiety symptoms, we used food allergy and generalized anxiety symptoms at the prior assessment to predict current generalized anxiety symptoms, controlling for sex and age. In other words, we predicted changes in generalized anxiety symptoms from one assessment to the next. In these assessment-to-assessment analyses, only subjects with multiple waves/assessments of data were included and subjects with more than two assessments contributed multiple observations. The total N of observations for these analyses was 3,900 (out of a possible 4,050 assessment-to-assessment pairs of observations).

Results

Prevalence and basic correlates of food allergy

The total N for food allergies in the past 12 months was 136 (weighted prevalence = 2.9%), with N = 76 (3.8%) for females, and N = 63 (2.1%) for males. The recent NHANES prevalence for clinical food allergies for ages 6-19 was slightly higher at 3.8% (6), but included younger children and was collected in 2005-2006. Data collection for the present study took place earlier (between 1994-2000), and our overall rate is quite similar to the 3.3% prevalence rate of food and digestive allergies reported by the CDC in 1997 (5). Consistent with other studies, food allergies here were more prevalent in younger than in older children (OR = .91, p = .04 for the prediction of food allergies with age). Consistent with previous work, children with food allergies were also more likely to have other atopic conditions, including asthma, and seasonal allergies/eczema (OR = 2.51, p = .008) and to have used medications in the past year (OR = 2.25, p = .001). Thus, rates of food allergy, and its correlates were consistent with results from studies that used either physician verified diagnoses or objective serologic measurement of food allergy (e.g., 6).

Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Analyses Using Psychopathology Symptoms

Means and standard deviations of psychopathology symptom scale scores for adolescents with and without food allergies are shown in Table 1 (white columns). On average, youth with food allergies had one more symptom of any psychopathology compared with those without food allergies. (Note that given our highly reliable 3-month time frame for assessing psychopathology, rates of symptoms are somewhat lower than they would be using a 12-month or lifetime time frame). Results from cross-sectional Poisson regressions (grey columns in Table 1) indicated that, controlling for sex and age, food allergies were associated with the following symptom scales at p < .05: any symptom, separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, ADHD, and anorexia nervosa. Next, these models were adjusted for other symptoms of psychopathology. Results showed that, controlling for comorbidity (i.e., other psychopathology symptom scales), separation anxiety and anorexia symptoms continued to be associated with food allergies at p < .05. These associations were also significant when parental reports of food allergy were linked to child-reported symptom scales as opposed to the combined parent-child reports (b = 0.42, p < .01, and b = 0.72, p < .05, respectively). Thus, associations between food allergy and both separation anxiety and anorexia nervosa symptoms were not due to the presence of other types of psychopathology symptoms or mono-reporter bias.

Table 1. Left Side: Means and standard deviations of symptoms of psychopathology in children without versus with food allergies. Right Side: Results from cross-sectional Poisson regression analyses testing differences in psychopathology symptoms between adolescents with versus without food allergies, adjusting for age and sex.

| Psychopathology Symptoms (Range of Symptoms in Sample) |

No FA | FA | Cross-Sectional Poisson Regression Analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | B | SE |

Means

ratio |

95% CI | |

| Any Symptom (0-51) | 3.35 | 4.34 | 4.48 | 5.73 | 0.30** | 0.11 | 1.35 | 1.09-1.69 |

| Separation Anxiety (0-7) | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.96**1 | 0.34 | 2.62 | 1.35-5.09 |

| Generalized Anxiety (0-6) | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 0.46*2 | 0.20 | 1.58 | 1.06-2.34 |

| Depression (0-10) | 0.76 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.21 | 0.21+ | 0.13 | 1.24 | 0.97-1.58 |

| Conduct Disorder (0-9) | 0.29 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.87 | 0.32+ | 0.19 | 1.38 | 0.95-2.00 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder (0-8) | 0.59 | 1.14 | 0.68 | 1.28 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 1.26 1.88 | 0.93-1.70 |

| ADHD (0-17) | 0.37 | 1.57 | 0.60 | 2.30 | 0.63** | 0.24 | 1.88 | 70 1.18-2.99 |

| Anorexia Nervosa3 (0-3) | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.89+1 | 0.35 | 2.43 | 1.21-4.86 |

| Bulemia Nervosa (0-3) | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.54 | −0.29 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 0.39-1.42 |

Notes: FA = Food Allergy, ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Stays significant at p < .05 when comorbidity controlled.

Stays significant at p < .10 when comorbidity controlled.

When underweight status was taken out of the anorexia nervosa scale, the bivariate means ratio was MR = 2.08, CI: .0.87-4.96, p < .10

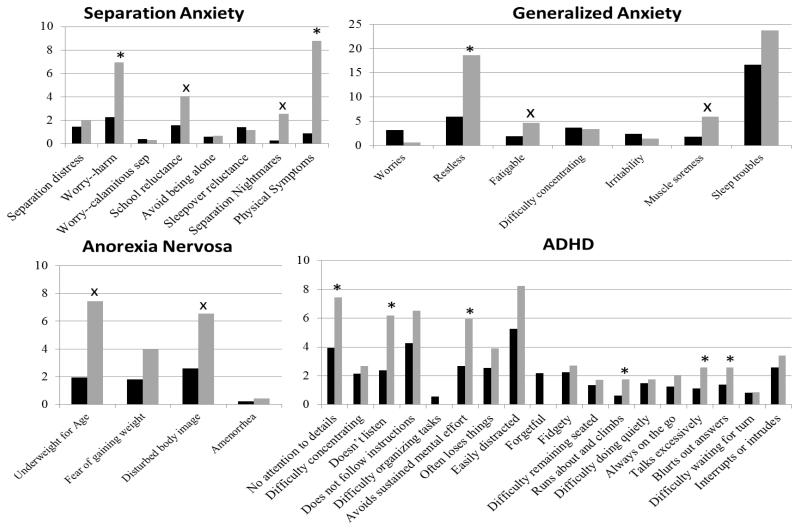

Considering the unique stressor faced, are there particular elevated individual symptoms driving these associations? In symptom-by-symptom analyses, we followed up symptoms scales that were associated with food allergies at p < .05. Figure 1 shows that, across disorders, nine symptoms of psychopathology were more prevalent in adolescents with food allergy as compared to adolescents without food allergies. The odds ratio for differences in several additional symptoms was greater than 2, but not significant at p < .05.

Figure 1.

Weighted prevalence (%) of individual symptoms of separation anxiety, anorexia nervosa, generalized anxiety, and ADHD. Black bars = no food allergy; grey bars = food allergy (FA). * = FA adolescents higher at p < .05; x = FA adolescents higher at OR > 2, but p > .05

Table 2 shows results from longitudinal analyses testing whether, controlling for sex and age, food allergies predicted increases in psychopathology symptoms over time. Food allergies predicted increases in generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms at p < .001, even when these models were adjusted for comorbidity. Thus, even when adjusting for multiple testing, food allergies significantly predicted increases in generalized anxiety and depression symptoms over time. When testing the opposite direction of effect (i.e., whether symptoms of psychopathology would predict an increased likelihood of food allergies over time), no significant associations were identified.

Table 2. Results from longitudinal Poisson regression analyses predicting increases in psychopathology symptoms with food allergies, adjusting for age, sex, and previous symptoms of psychopathology.

| Psychopathology Symptoms (Range of Symptoms in Sample) |

Longitudinal Poisson Regression Analyses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| B | SE |

Means

ratio |

95% CI | |

| Any Symptom (0-51) | 0.09 | 0.10 | 1.13 | 0.95-1.34 |

| Separation Anxiety (0-7) | 0.89+2 | 0.54 | 2.46 | 0.86-7.07 |

| Generalized Anxiety (0-6) | 0.53***1 | 0.16 | 1.73 | 1.29-2.34 |

| Depression (0-10) | 0.40***1 | 0.12 | 1.49 | 1.18-1.87 |

| Conduct Disorder (0-9) | −0.35 | 0.24 | 0.71 | 0.44-1.16 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder (0-8) | −0.05 | 0.18 | 0.96 | 0.67-1.37 |

| ADHD (0-17) | −0.08 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 0.54-1.67 |

| Anorexia Nervosa (0-3) | 0.74 | 0.47 | 2.10 | 0.84-5.23 |

| Bulemia Nervosa (0-3) | 0.28 | 0.35 | 1.33 | 0.67-2.65 |

Notes: FA = Food Allergy, ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Stays significant at p < .05 when comorbidity controlled.

Stays significant at p < .10 when comorbidity controlled.

Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Analyses Using Psychopathology Diagnoses

Next, we conducted analyses predicting psychiatric diagnoses with food allergy—cross-sectionally and at the next assessment (Table 3). Specifically, we predicted the occurrence of “any diagnosis,” and then individual separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and ADHD diagnoses. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa were not included here because too few cases met diagnostic criteria. Results from these cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses showed that adolescents with versus without food allergies did not differ significantly in the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders.

Table 3. Results from logistic regression analyses predicting DSM-IV diagnoses with food allergy – cross-sectionally and over time. Odds ratios are adjusted for sex and age in the cross-sectional analyses, and also for previous diagnosis in the longitudinal analyses.

| Cross-Sectional | Longitudinal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | CI | |

| Any Disorder | 0.76 | 0.47-1.22 | 1.32 | 0.59-2.93 |

| Separation Anxiety | 2.31 | 0.79-6.79 | 2.85 | 0.76-10.70 |

| Generalized Anxiety | 0.70 | 0.15-3.22 | 1.13 | 0.25-5.38 |

| Depression | 0.87 | 0.39-1.96 | 0.97 | 0.37-2.51 |

| Conduct Disorder | 1.36 | 0.64-2.90 | 0.78 | 0.28-2.14 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 1.09 | 0.60-2.02 | 1.11 | 0.28-1.69 |

| ADHD | 2.39+ | 0.93-6.13 | 0.69 | 0.14-9.00 |

Notes: OR = Odds ratio

p < .10

Anorexia and Bulemia Nervosa not included in Table, because the prevalence of these disorders was too low.

Testing Sex Differences and Ruling out Alternative Explanations

Previous research on adults reported that associations between food allergies and psychopathology may differ in females and males (19). Therefore, follow-up analyses tested for moderation by sex by including a food allergy by sex interaction in the prediction of psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses. No statistically significant interactions were identified.

Follow-up analyses also examined whether associations between food allergies and psychopathology were accounted for by alternative variables. Individuals with food allergies here and in other studies are more likely to have other atopic conditions (6), some of which tend to be associated with elevated symptoms of psychopathology (28). Furthermore, children with food allergies here were more likely to have used medication in the past year, but side effects of medications taken in the context of food allergies (e.g., antihistamines, steroids, epinephrine) could include fatigability, sleep troubles, and restlessness, which, in turn, could be captured as symptoms of generalized anxiety, depression, and ADHD. Thus, in follow-up analyses, the number of other atopic conditions and medication use were adjusted for, but previous pattern of findings remained unchanged when taking these potential alternative explanations into account. Finally, the results reported in all tables replicated when adjusting models for low socioeconomic status and parental depression, and, thus are independent of these indicators of parental mental health and stress.

Discussion

Living with food allergies poses a unique stressor for adolescents: food that is omnipresent in their lives and necessary for survival triggers physiological reactions that range from signals of adaptive functioning (e.g., the gut motility of digestion) to threats to survival (life-threatening anaphylaxis). The only known successful management strategy for food allergies is strict allergen avoidance (8), resulting in disruptions of daily life (12), and converting staples of adolescents’ activities—eating lunch in the cafeteria or celebrating birthdays with friends—into risks for inadvertent allergen ingestion (29). No research has examined links between food allergies and symptoms of emotional, disruptive, and eating disorders in adolescents from the community.

On average, adolescents with food allergies had one more symptom of psychopathology spanning symptoms of emotional, disruptive, and eating disorders than those without; they also increased in their symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety over time. Elevated symptoms of psychopathology were, however, not matched by an increased risk for meeting diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV disorders. One possible interpretation of these results is that the elevated “symptoms” do not, in fact, reflect cohesive syndromes of psychopathology, but rather reasonable adaptations to living with food allergy. Such necessary adaptations involve increased vigilance to external and internal stimuli involving increased risk for food-induced allergic reactions (8), which could manifest as concerns about being away from home, caution around eating, and diligent monitoring of body functions.

Primary caregivers typically create a safe food environment at home, and a high proportion of serious food-induced allergic reactions occur away from home (30). Consequently, separations from parents may signal increased risk for inadvertent allergen ingestion and also the absence of a competent first responder (i.e., the parent) in the event of a serious food-induced allergic reaction (31). Thus, despite a general developmental trend toward declines in separation anxiety during adolescence (22), adolescents with food allergies had elevated symptoms on this scale. This finding is consistent with a smaller study using a clinic-based sample of somewhat younger youth (15).

In the context of food allergy, increased vigilance is also necessary during food intake itself. Ingesting very small amounts of a food allergen—less than half a gram in the case of some food allergens—is sufficient to induce severe allergic reactions (32), even in an individual who previously only had mild reactions. Thus, the strict avoidance of food allergens is a primary treatment strategy for patients with food allergy (32). Strict allergen avoidance has been shown to be associated with lower risk for obesity and being overweight (33, 34). In our study, adolescents with food allergy were also at increased risk for eating disorders symptoms, even beyond “just” being underweight. Additional research is needed to examine whether elevated symptoms of anorexia nervosa are limited to healthy adaptations to food allergy or actually represent a long-term risk for eating disorders for some adolescents. Given the changes in life style and food intake necessary in the context of food allergy, it is likely that, at a minimum, eating habits and behaviors, and feelings and cognitions about food and one’s body will be altered.

When living with food allergy, increased vigilance also needs to be exercised with respect to internal stimuli. Changes in body functions could signal an unfolding allergic reaction; detecting such signals could be life-saving. Such increased vigilance to internal stimuli could also increase adolescents’ interoceptive sensitivity [i.e., the awareness of change in visceral organs (35, 36)] — to all somatic cues. In our study, food allergy was associated with physical symptoms across disorders (e.g., physical symptoms during/in anticipation of separations from parents, restlessness in generalized anxiety). In prior work, youth with food allergies also reported more abdominal pain, diarrhea, skin rash, fatigue, and flatulence even compared to age-mates with other digestive disorders (12). Such high attention to bodily functions could, at times, be maladaptive, for example when it becomes difficult to disengage attention from internal signals to pay attention to external events, such as instructions from parents/teachers, or activities that require mental effort. Thus, increased interoception could account for some of the elevated symptoms of ADHD, especially symptoms of inattention.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

First, the GSMS is representative of the communities from which it was sampled, but not of the US population. Findings should be replicated in samples that include Hispanic and Asian participants. Second, because the GSMS is a community-based study, our measure of food allergies was parent-reported, and not physician-verified. Thus, it is possible that some parents reported food-related medical conditions here that would not be classified as a food allergy by a physician. However, correlates of food allergy in our study (e.g., younger age, presence of other atopic conditions) were consistent with correlates in studies using either physician-verified or serological data. Indeed, our findings regarding separation anxiety were also consistent with data from a younger, physician-verified patient sample (15). Third, we did not assess the number, severity, or type of food allergies or history of past reactions, but multiple, severe, or specific food allergies may be associated with the highest risk for psychopathology.

Fourth, both, prevalence of food allergies and 3-month psychiatric disorders are relatively low. It is possible that with even more than our 5,000+ observations and a 12-month assessment of psychopathology, significant associations between food allergy and psychiatric diagnoses would have been detected, including between food allergy and later separation anxiety disorder. Indeed, unlike our study, one previous study with adults had detected significant associations between food allergy and increased risk for psychiatric diagnoses (16). However, in that study, most of the significant findings were for disorders that are still rare during much of adolescence and become somewhat more common in adulthood (e.g., panic disorder) – thus, our lack of diagnostic findings is not entirely inconsistent with findings from that study. Finally, the symptom-by-symptom analyses were exploratory. Considering the number of statistical tests conducted in these analyses, and the low 3-month prevalence of many single symptoms of psychopathology, results from symptom-by-symptom analyses should be interpreted with caution.

Future research should explicitly measure interoceptive sensitivity to examine whether this mechanism indeed underlies some of the elevated symptoms of psychopathology in adolescents with food allergies. In addition, the possible mediational role of actual immune responses in linkages between food allergies and psychopathology symptoms should be investigated. Allergen-specific IgE antibodies may increase food aversions (37). Immune responses could also induce elevated symptoms of depression (38) and anxiety (39). Finally, familial transmission of psychopathology symptoms should be examined. Parents of children with food allergies report “living with fear” (40) and having higher levels of overall anxiety, separation anxiety, and physical symptoms (15, 29, 41). Thus, adolescents’ symptoms of psychopathology could be a consequence of their parents’ rather than their own reaction to living with food allergy. Genetic transmission of predispositions to both allergy and symptoms of psychopathology could also play a role in familial transmission.

Considering the potentially life-threatening and unpredictable nature of living with food allergy, associations with psychopathology in our study were weaker than expected. Indeed, the unique constellation of increased symptoms of psychopathology in this context likely reflects an adaptive increase in vigilance. However, for achieving long-term healthy psychological and physical development, support and guidance is crucial in helping adolescents with food allergies achieve an optimal balance between necessary vigilance and hypervigilance and unnecessary restriction.

Highlights.

Concurrently, food allergies were associated with some psychopathology symptoms.

Over time, food allergies predicted increases in generalized anxiety/depression.

Food allergies were not linked with psychiatric disorders.

Some increases in vigilance are likely adaptive in the context of food allergies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH63970, MH63671, MH48085, MH094605), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301), and the William T. Grant Foundation. We thank the participants and their parents for their cooperation.

L.S. is also currently funded by NIH grants HD078346 and DA036523. N.Z. is currently also funded by grant MH097959. W.E.C. is also currently also funded by DA011301, U01AA021681, and DA036523. A.A. is currently also funded by. E.J.C. is currently also funded by NIH grants R01DA011301, P30 DA023026, R01 DA022308. A.A. is currently also funded by DA023026, DA024413, DA022308.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grundy J, Matthews S, Bateman B, Dean T, Arshad SH. Rising prevalence of allergy to peanut in children: Data from 2 sequential cohorts. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;110(5):784–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.128802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branum AM, Lukacs SL. Food allergy among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1549–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e9–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venter C, Arshad SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58(2):327–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuehn BM. Food allergies becoming more common. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2358. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu AH, Jaramillo R, Sicherer SH, Wood RA, Bock SA, Burks AW, et al. National prevalence and risk factors for food allergy and relationship to asthma: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;126(4):798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings AJ, Knibb RC, King RM, Lucas JS. The psychosocial impact of food allergy and food hypersensitivity in children, adolescents and their families: A review. Allergy. 2010;65(8):933–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JS, Sicherer SH. Living with food allergy: Allergen avoidance. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58(2):459–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(4):375–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons AC, Forde EM. Food allergy in young adults: Perceptions and psychological effects. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(4):497–504. doi: 10.1177/1359105304044032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marklund B, Ahlstedt S, Nordström G. Health-related quality of life in food hypersensitive schoolchildren and their families: parents’ perceptions. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4(48) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calsbeek H, Rijken M, Bekkers MJ, Dekker J, van Berge Henegouwen GP. School and leisure activities in adolescents and young adults with chronic digestive disorders: Impact of burden of disease. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;13(2):121–30. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1302_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostblom E, Egmar AC, Gardulf A, Lilja G, Wickman M. The impact of food hypersensitivity reported in 9-year-old children by their parents on health-related quality of life. Allergy. 2008;63(2):211–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avery NJ, King RM, Knight S, Hourihane JO. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2003;14(5):378–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King RM, Knibb RC, Hourihane JO. Impact of peanut allergy on quality of life, stress and anxiety in the family. Allergy. 2009;64(3):461–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patten SB, Williams JV. Self-reported allergies and their relationship to several Axis I disorders in a community sample. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2007;37(1):11–22. doi: 10.2190/L811-0738-10NG-7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Erkanli A, Costello EJ, Angold A. Indirect comorbidity in childhood and adolescence. Frontiers in Psychiatry. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00144. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):764–72. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timonen M, Jokelainen J, Silvennoinen-Kassinen S, Herva A, Zitting P, Xu B, et al. Association between skin test diagnosed atopy and professionally diagnosed depression: A Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(4):349–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muñoz-Furlong A, Weiss CC. Characteristics of food-allergic patients placing them at risk for a fatal anaphylactic episode. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 2009;9(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Erkanli A, Stangl DK, Tweed DL. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Functional impairment and serious emotional disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(12):1137–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120077013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Child Behavior Profile. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25(4):755–62. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ascher BH, Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Angold A. The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA): Description and psychometrics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1996;4(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett DS. Depression among children with chronic medical problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1994;19:149–69. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/19.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bollinger ME, Dahlquist LM, Mudd K, Sonntag C, Dillinger L, McKenna K. The impact of food allergy on the daily activities of children and their families. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2006;96(3):415–21. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudd K, Wood RA. Managing food allergies in schools and camps. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58(2):471–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keet C. Recognition and management of food-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58(2):377–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burks AW. Peanut allergy. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1538–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukaida K, Kusunoki T, Morimoto T, Yasumi T, Nishikomori R, Heike T, et al. The effect of past food avoidance due to allergic symptoms on the growth of children at school age. Allergology International. 2010;59(4):369–74. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-OA-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flammarion S, Santos C, Guimber D, Jouannic L, Thumerelle C, Gottrand F, et al. Diet and nutritional status of children with food allergie. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2011;22(2):161–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3(8):655–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cameron OG. Interoception: The inside story--a model for psychosomatic processes. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63(5):697–710. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirotti L, Mucida D, de Sá-Rocha LC, Costa-Pinto FA, Russo M. Food aversion: A critical balance between allergen-specific IgE levels and taste preference. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2010;24(3):370–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irwin MR, Miller AH. Depressive disorders and immunity: 20 years of progress and discovery. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2007;21(4):374–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Papageorgiou C, Tsetsekou E, Soldatos C, Stefanadis C. Anxiety in relation to inflammation and coagulation markers, among healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185(2):320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillespie CA, Woodgate RL, Chalmers KI, Watson WT. “Living with risk”: Mothering a child with food-induced anaphylaxis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2007;22(1):30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sicherer SH, Noone SA, Muñoz-Furlong A. The impact of childhood food allergy on quality of life. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2001;87(6):461–4. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]