Abstract

The conserved kinases PAR-1/MARK are critically involved in processes such as asymmetric cell division, cell polarity and neuronal differentiation. Their deregulation has been implicated in diseases including Alzheimer’s disease and cancer. Given the importance of PAR-1/MARK in health and disease, their activities need to be tightly controlled. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying their regulation in vivo. Here we show that in Drosophila, a phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination mechanism restrains PAR-1 activation. Active PAR-1 generated by LKB1-controlled phosphorylation is targeted for ubiquitination and degradation by SCF (Skp, Cullin, F-box containing complex) (Slimb), whose action is antagonized by the deubiquitinating enzyme fat facets. This newly identified PAR-1-modifying module critically regulates synaptic morphology and tau-mediated postsynaptic toxicity of amyloid precursor protein (APP)/Aβ-42, the causative agents of Alzheimer’s disease, at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Our results provide new insights into the regulation of PAR-1 in various physiological processes and offer new therapeutic strategies for diseases involving PAR-1/MARK deregulation.

PAR-1 encodes a highly conserved polarity-regulating kinase originally identified in Caenorhabditis elegans1. In multicellular organisms, PAR-1 homologues are critically involved in diverse processes, from cell polarization to Wnt signalling, immunity and metabolism2,3. In the nervous system, PAR-1 and its mammalian homologues, the microtubule affinity-regulating kinases MARK1–MARK44,5, regulate neuronal polarization, differentiation, migration and synaptogenesis. The diverse physiological functions of these kinases are likely mediated by a large repertoire of substrates2. One main mechanism of PAR-1/MARK action is to regulate microtubule dynamics through its substrate tau4,6, whose aberrant phosphorylation is associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related tauopathies7.

The detrimental consequences of deregulation or dysfunction of PAR-1/MARKs entail a stringent control over their activities in vivo. PAR-1/MARK activity can be regulated by phosphorylation, intra-molecular interaction and inter-molecular interaction2. Certain kinases have been implicated in phosphorylating PAR-1/ MARKs. For example, phosphorylation by LKB1 and MARKK both positively regulate PAR-1/MARK activity, and LKB1 has been shown to promote PAR-1 activity in AD-related processes8–10. It is not known how the active phospho-PAR-1 (p-PAR-1) generated by LKB1 and/or MARKK action is regulated in vivo.

Protein ubiquitination and deubiquitination have essential roles in cell signalling during development and in tissue maintenance in adults. Defects in this process contribute to disease conditions, such as neurodegeneration and cancer11,12. The SCF (Skp_Cul1_F-box) E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligase complex is primarily involved in ubiquitinating phospho-substrates, with the F-box-containing subunit recognizing and recruiting phospho-targets13. Hence, the SCF complex is particularly important for kinase signalling. One of the well-studied SCF complexes is the Drosophila SCF(Slimb)14 and its mammalian counterpart SCF(β-TrCP)15, which contain the F-box proteins Slimb and β-TrCP, respectively, and are critically involved in diverse processes13,16. The effects of ubiquitination on the turnover or activity of target proteins are counteracted by deubiquitinating enzymes17. In Drosophila, the deubiquitinating enzyme fat facets (FAFs) has been implicated in synapse development18. Whether SCF(Slimb) and FAF may interact during synapse development by targeting common synaptic substrates is not known.

In genetic screens for modifiers of PAR-1 in Drosophila, we have uncovered a regulatory mechanism involving LKB1, SCF(Slimb) and FAF. Activated p-PAR-1 generated by LKB1-controlled phosphorylation is targeted for ubiquitination and degradation by SCF(Slimb), whose action is antagonized by FAF. These studies identify PAR-1 as the first common substrate for SCF(Slimb) and FAF. In Drosophila AD models, this newly identified PAR-1-modifying module critically regulates the toxicity of amyloid precursor proteins (APP)/Aβ-42, leading candidates for the causative agents of AD19, at the postsynapse of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), and it acts by influencing tau. These results thus offer mechanistic insights into the in vivo regulation of an important kinase, with particular relevance for understanding the synaptic mechanisms of AD pathogenesis.

Results

Identification of FAF as a deubiquitinating enzyme of PAR-1

To identify novel regulators of PAR-1, we performed a genetic screen for modifiers of a degeneration phenotype caused by GMR-Gal4>PAR-1 in the retina6. A strong modifier came out of this screen was FAF. A FAF-overexpressing EP line (EP381), which alone caused a mild rough eye phenotype, likely due to its moderate upregulation of endogenous PAR-1 protein level (Supplementary Fig. S1), caused a dramatic reduction of eye size when introduced into GMR-Gal4>PAR-1 background (Fig. 1a–d). This effect of FAF is specific, as the co-expression of a different deubiquitinating enzyme Cylindromatosis (CYLD)20 failed to modify the GMR-Gal4>PAR-1 phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Conversely, introduction of a FAF RNA interference (RNAi) transgene, which was effective in knocking down FAF mRNA and protein expression (Supplementary Fig. S3), partially suppressed GMR-Gal4>PAR-1 effect (Supplementary Fig. S4).

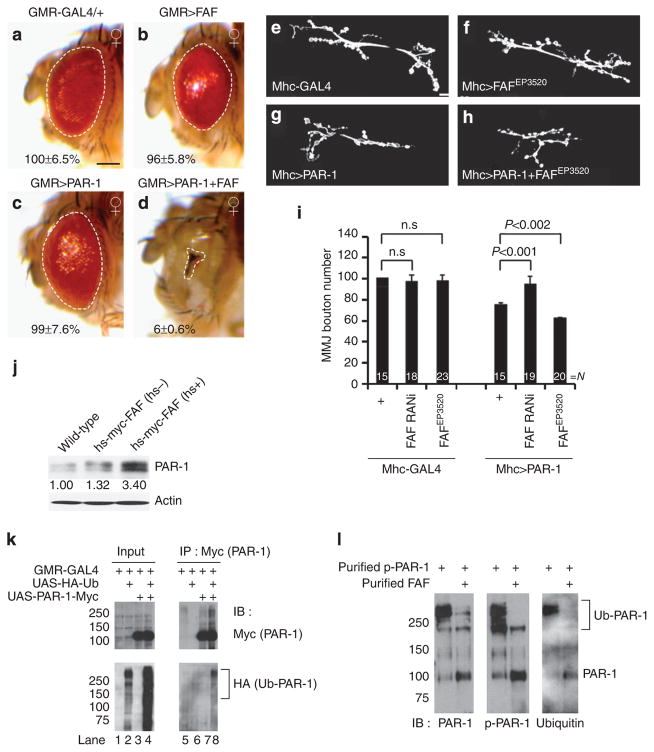

Figure 1. FAF positively regulates PAR-1 activity and protein stability.

(a–d) Genetic interaction between PAR-1 and FAF in the fly retina. All flies were grown at 25 °C. Images of female flies are shown. The genotypes are: GMR-Gal4/ +control (a), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 (b), GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 (c) and GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 +FAFEP381 (d) (n =16, 17, 16 and 16 animals, respectively). Statistically significant differences are P<0.001 (GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1, GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 +FAFEP381) as determined by Student’s t-test. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Dashed lines outline the eye contour. Values represent areas of retinal surface normalized with GMR-Gal4/ +control. Scale bar (a–d), 100 μm. (e–h) Representative NMJ terminals of the indicated genotypes revelled by anti-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) immunostaining. The genotypes are Mhc-Gal4/ +control (e), Mhc-Gal4>FAFEP3520 (f), Mhc-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 (g) and Mhc-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 +FAFEP3520 (h). Scale bar (e–h), 10 μm (i) Quantification of the total number of boutons per muscle area on muscle 6/7 of A3 in the indicated genotypes. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (j) Western blot analysis of endogenous PAR-1 protein level after FAF induction from hs-Myc-FAF. Actin serves as a loading control. Values represent PAR-1 levels normalized with wild-type control in three independent experiments. (k) Western blot analysis showing in vivo ubiquitination of PAR-1 in animals co-expressing PAR-1-Myc and HA-Ub (lane 8). (l) In vitro deubiquitination assay using affinity-purified, HA-Ub-modified phsopho-PAR-1 as the substrate, and affinity-purified FAF as the enzyme. Note the decrease of poly-ubiquitinated PAR-1 and the corresponding increase of non-ubiquitinated or mono-ubiquitinated PAR-1 after FAF treatment. Brackets indicate ubiquitinated PAR-1 (Ub-PAR-1) in (k,l.). IB, immunoblot; n.s., not significant.

We also tested the functional interaction between PAR-1 and FAF in a different context. When overexpressed at the postsynapse of the larval NMJ, Mhc-Gal4>PAR-1 exerted synaptic toxicity as shown by a marked loss of boutons21. Although FAF overexpression or FAF-RNAi alone had no discernable effect on NMJ synapse morphology, which is likely due to the alterations of endogenous PAR-1 level not reaching a threshold level required for toxicity (Supplementary Fig. S1), in Mhc-Gal4>PAR-1 background, FAF-RNAi rescued the loss of boutons formed on muscle 6/7, whereas FAF overexpression showed significant enhancement (Fig. 1e–i). The co-expression of CYLD failed to modify the effect of PAR-1 at the NMJ (Supplementary Fig. S2b), supporting FAF as a positive regulator of PAR-1.

Ub-specific protease 9X (USP9X), the putative mammalian homologue of FAF, was previously identified as a binding partner of MARK4 (refs 22,23), but the functional effect of this interaction was not well defined. Using an hs-FAF-myc transgene24, we found that endogenous PAR-1 level was dramatically increased after heat shock (hs +) (Fig. 1j). In contrast, the overexpression of CYLD failed to alter PAR-1 level (Supplementary Fig. S5). To test whether FAF acts as a deubiquitin enzyme of PAR-1, we first tested whether PAR-1 is normally ubiquitinated in vivo. We co-expressed UAS-PAR-1-myc and UAS-HA-Ub in the eye. Transgenic PAR-1 was then subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Myc, and its ubiquitination status was tested by western blotting with anti-HA. A smear of HA immunoreactivity was detected in PAR-1 IP (Fig. 1k), indicating poly-ubiquitination of PAR-1 in vivo. Moreover, in faf mutant tissue extracts, we observed moderately increased ubiquitination of PAR-1 (Supplementary Fig. S6a), and the effect was more dramatic when p-T408-PAR-1 (Supplementary Fig. S6b), which corresponds to an activated form of PAR-1 (ref. 10) was analysed (Supplementary Fig. S6). These data support p-PAR-1 as a physiological substrate of FAF. To test whether FAF directly de-ubiquitinates PAR-1, we used affinity-purified FAF and HA-Ub-labelled PAR-1 in an in vitro reaction. FAF clearly reduced poly-ubiquitinated PAR-1 level in vitro (Fig. 1l), supporting that FAF directly de-ubiquitinates PAR-1.

SCF(Slimb) as an E3 that antagonizes FAF in regulating PAR-1

We were interested in identifying the E3 Ub ligase for PAR-1. Based on the assumption that the E3 for PAR-1 would exhibit strong functional interaction with FAF, we performed genetic interaction tests between FAF and candidate E3s for whom gain-of-function or loss-of-function alleles were available. One strong interacting gene was Slimb. Inhibition of Slimb expression using a Slimb-RNAi transgene, which efficiently knocked down Slimb protein expression (Supplementary Fig. S7c), resulted in increased endogenous PAR-1 or transgenic PAR-1 protein levels (Supplementary Figs S1b and S7c) and induced NMJ and eye phenotypes similar to that caused by PAR-1 overexpression (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, although co-overexpression of a wild-type (WT) Slimb transgene with FAF(EP381) had roughly the same effect (Fig. 2g) as overexpression of FAF(EP381) alone (Fig. 2f), co-expression of a Slimb-RNAi transgene with FAF(EP381) resulted in dramatically reduced eye size (Fig. 2h), similar to that seen after PAR-1 and FAF(EP381) co-expression (Fig. 1d). Co-expression of FAF(EP381) and Slimb-ΔF, a dominant-negative form of Slimb14, also caused eye size reduction, albeit less dramatic than FAF(EP381)/Slimb-RNAi co-expression, and the resulting animals exhibited dark patches of necrotic tissues not seen in animals expressing either transgene alone (Fig. 2i). Supporting the specificity of FAF and Slimb interaction, Archipelago (Ago), another F-box component of SCF25, did not interact with FAF (Supplementary Fig. S8), and Slimb did not exhibit obvious interaction with CYLD (Supplementary Fig. S9).

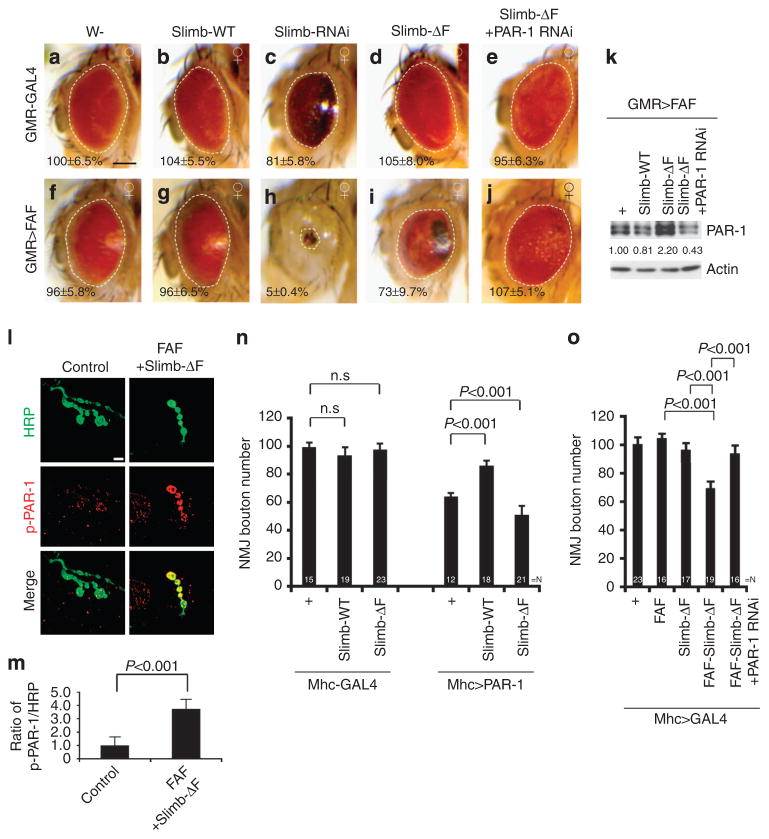

Figure 2. PAR-1 serves as a common substrate for FAF and Slimb.

(a–j) Genetic interaction between FAF and Slimb in the retina. All flies were grown at 25°C. Images of female flies are shown. The genotypes are: GMR-Gal4/ +control (a), GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-WT (b), GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi (c), GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-ΔF (d), GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-ΔF +UAS-PAR-1-RNAi (e), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 (f), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-WT (g), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-RNAi (h), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF (i) and GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-SlimbΔF +UAS-PAR-1-RNAi (j) (n =16, 17, 17, 18, 16,17, 16, 18, 16 and 16 animals, respectively). Statistically significant differences are P<0.001 (GMR-Gal4/ +control, GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi; GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381, GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-RNAi; GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381, GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF; GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF, GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-SlimbΔF +UAS-PAR-1-RNAi ) as determined by Student’s t-test. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Dashed lines outline the eye contour. Values represent areas of retinal surface normalized with GMR-Gal4/ +control. (a–j) Scale bar, 100 μm. (k) Western blot analysis of PAR-1 protein levels in the indicated genotypes. Actin serves as a loading control. Values represent PAR-1 levels in the indicated genotypes normalized with GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 control in three independent experiments. (l) Double labelling of larval NMJs with anti-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in green and anti-p-PAR-1 in red. Merged images are shown in lower panels. The genotypes are: Mhc-Gal4>FAF +Slimb-ΔF and Mhc-Gal4/ +control. Scale bar, 5 μm. (m) Quantification of p-PAR-1 signals in l and m after normalization with HRP signal. (n) Quantification of bouton numbers showing genetic interaction between PAR-1 and Slimb at the NMJ. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (o) Quantification of bouton numbers showing genetic interactions among Slimb, FAF, and PAR-1 at the NMJ. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

To verify that the genetic interaction between Slimb and FAF was mediated by PAR-1, we co-expressed a PAR-1-RNAi transgene, whose efficiency was characterized before21. This resulted in suppression of the synthetic toxicity between FAF and Slimb-ΔF (Fig. 2j) or between FAF and Slimb-RNAi (Supplementary Fig. S10), suggesting that FAF and SCF(Slimb) both acted on PAR-1. If PAR-1 were a common target through which deregulated Slimb and FAF activities resulted in eye degeneration, we would expect to see altered endogenous PAR-1 protein levels under those conditions. Indeed, FAF(EP381)/Slimb-ΔF co-expression led to a significant increase of PAR-1 protein level, whereas FAF(EP381)/Slimb-WT co-expression led to a modest decrease (Fig. 2k).

Given the role of SCF(Slimb) in targeting phospho-proteins for degradation, we tested whether SCF(Slimb) might affect p-T408-PAR-1. As shown in Fig. 2l, p-PAR-1 was present at low levels in the postsynaptic membrane in control NMJ, as reported before21. In animals co-expressing FAF and Slimb-ΔF, the level of p-PAR-1 was significantly increased (Fig. 2l,m). The specificity of this p-PAR-1 staining is supported by the significant increase of staining signals in animals overexpressing LKB1 (Supplementary Fig. S11), the kinase responsible for PAR-1 T408 phosphorylation10.

To test for a functional link between PAR-1 and Slimb in NMJ synaptic morphogenesis, we examined whether p-PAR-1 co-localized with Slimb. Slimb formed punctate structures that co-localized with p-PAR-1 at the NMJ (Supplementary Fig. S12a). The Slimb-positive signals were dramatically reduced when Slimb was knocked down postsynaptically in Mhc-Gal4>UAS-Slimb RNAi, but only mildly reduced when Slimb was knocked down presynaptically in elav-Gal4>UAS-Slimb RNAi (Supplementary Fig. S12b). This result, together with the significant loss of boutons in Mhc-Gal4>UAS-Slimb RNAi but not elav-Gal4>UAS-Slimb RNAi animals (Supplementary Fig. S7a,b), suggested that like PAR-1 (ref. 21), Slimb has a more prominent role at the postsynapse.

We next used the NMJ to further investigate the relationships among Slimb, FAF and PAR-1. Postsynaptic overexpression of PAR-1 resulted in ~ 40% reduction of NMJ boutons (Fig. 2n), an effect rescued by the co-expression of Slimb-WT but enhanced by Slimb-ΔF (Fig. 2n). Dlg was previously shown to be a key substrate mediating the effect of PAR-1 on synaptic morphology, and it is delocalized from the postsynapse by PAR-1 (ref. 21). The effect of PAR-1 overexpression on Dlg localization was rescued by Slimb-WT (Supplementary Fig. S13), consistent with Slimb negatively regulating PAR-1 function. Moreover, although postsynaptic expression of either FAF(EP381) or Slimb-ΔF had no obvious effect on NMJ bouton number, presumably because of their moderate effects on endogenous PAR-1 level (Supplementary Fig. S1a), their co-expression resulted in an ~ 40% loss of boutons, which was blocked by PAR-1-RNAi (Fig. 2o). These results are consistent with FAF and Slimb having antagonistic roles in regulating the abundance of PAR-1 protein. Deregulation of this process could lead to the accumulation of activated p-PAR-1 and ensuing synaptic toxicity.

Evidence that p-PAR-1 is a direct target of SCF(Slimb)

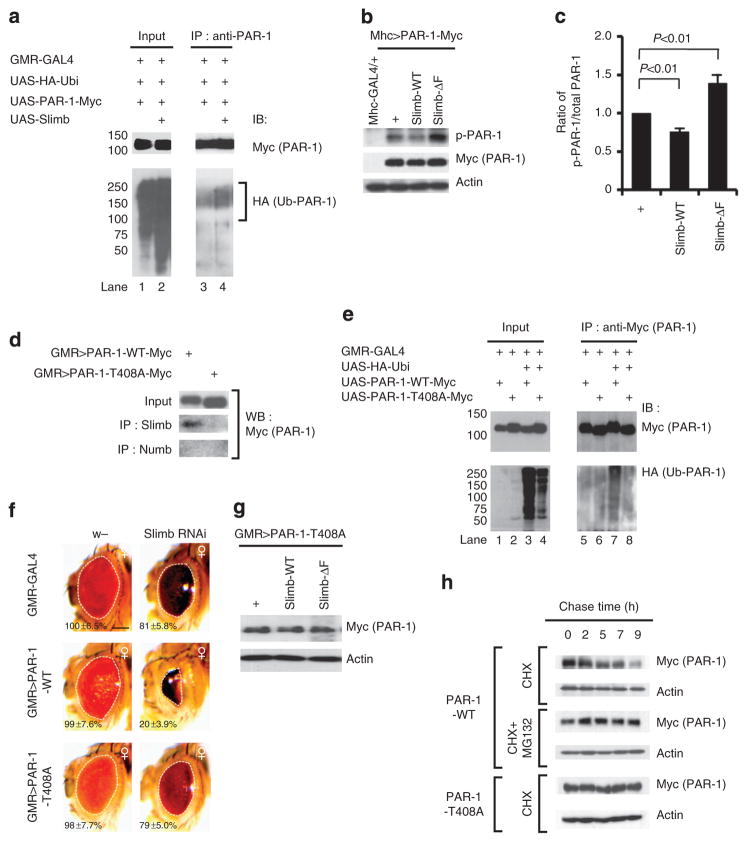

The genetic and biochemical evidence presented so far are consistent with SCF(Slimb) directly targeting PAR-1. To test this possibility, we used the in vivo ubiquitination assay as described in Fig. 1k to examine the effect of Slimb on PAR-1 ubiquitination. Overexpression of Slimb led to increased PAR-1 ubiquitination (Fig. 3a). We also examined the effects of Slimb-WT and Slimb-ΔF on the steady-state levels of p-PAR-1 and total PAR-1 expressed from a UAS-PAR-1 transgene. Slimb-WT decreased, whereas Slimb-ΔF increased, the ratio of p-PAR-1/total PAR-1 (Fig. 3b,c), suggesting that SCF(Slimb) preferentially promotes the degradation of p-PAR-1. Consistently, endogenous p-PAR-1 level was increased by Slimb-RNAi (Supplementary Fig. S7c). In co-IP experiments using fly head extracts prepared from animals expressing PAR-1-WT or PAR-1-T408A mutant in the eye, PAR-1-WT but not PAR-1-T408A interacted with endogenous Slimb, supporting that Slimb preferentially recognizes p-T408-PAR-1 (Fig. 3d). This is consistent with role of the F-box subunit of SCF in recognizing and recruiting phospho-targets13. Correlated with decreased binding of PAR-1-T408A to Slimb, the in vivo ubiquitination of PAR-1-T408A was greatly diminished compared with PAR-1-WT (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, unlike PAR-1-WT, whose eye phenotype and steady-state level were negatively regulated by Slimb, PAR-1-T408A was no longer responsive to Slimb (Fig. 3f,g).

Figure 3. SCF Slimb-mediated ubiquitination of PAR-1 is coupled to its phosphorylation at T408.

(a) Western blot analysis showing enhanced in vivo ubiquitination of PAR-1 by Slimb. (b) Western blot analysis showing effects of Slimb-WT or Slimb-ΔF on transgene-derived total PAR-1 and p-PAR-1 levels. Actin serves as a loading control. (c) Quantification of the ratio of p-PAR-1/total PAR-1 levels shown in b. (d) IP experiment showing selective binding of Slimb to PAR-1-WT compared with PAR-1-T408A. Anti-Numb IP serves as a negative control. (e) In vivo ubiquitination assay showing reduced ubiquitination of PAR-1-T408A compared with PAR-1-WT. (f) Genetic interaction between PAR-1 and Slimb in the retina in each of the indicated genotypes (GMR-Gal4/ +control, n =16; GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi, n =17; GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1-WT, n =16; GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1-WT +UAS-Slimb-RNAi, n =16; GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1-T408A, n =17; and GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1-T408A +UAS-Slimb-RNAi, n =17). Statistically significant differences are P<0.001 (GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1-WT, GMR-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1-WT +UAS-Slimb-RNAi) as determined by Student’s t-test. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Dashed lines outline the eye contour. Values represent areas of retinal surface normalized with GMR-Gal4/ +control. Scale bar, 100 μm. (g) Western blot analysis showing non-responsiveness of PAR-1-T408 protein abundance to Slimb activity. Actin serves as a loading control. (h) Pulse-chase assay showing differential stability of PAR-1-WT and PAR-1-T408A in HEK293 cells. Actin serves as a loading control. IB, immunoblot.

To further demonstrate that SCF(Slimb) targets p-T408 PAR-1 for ubiquitination and degradation, we performed pulse-chase experiments in HEK293 cells transfected with myc-tagged PAR-1-WT or PAR-1-T408A and in the presence of the translation inhibitor cycloheximide. Although PAR-1-WT was gradually degraded during the chase period in a proteasome-dependent manner, PAR-1-T408A remained stable (Fig. 3h). Collectively, these data demonstrate that SCF(Slimb) targets p-PAR-1 for ubiquitination and degradation.

LKB1 kinase cooperates with SCF(Slimb) to regulate PAR-1

LKB1 phosphorylates PAR-1 at the T408 site10. We tested whether LKB1 cooperates with SCF(Slimb) to regulate PAR-1. We first examined the localization and biochemical interaction of LKB1 with PAR-1 in vivo using an LKB1-GFP transgene. LKB1-GFP clearly localizes to the NMJ synapse when expressed postsynaptically (Supplementary Fig. S14), and LKB1-GFP co-IPs with endogenous PAR-1 (Supplementary Fig. S15a). We next tested the relationships among LKB1, Slimb and PAR-1 at the NMJ. Like PAR-1, LKB1 induced a strong bouton-loss phenotype when overexpressed postsynaptically (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S15b, c). This effect was blocked by PAR-1-RNAi (Fig. 4a), consistent with LKB1 being an upstream activating kinase for PAR-110. Previous studies established Dlg as a key substrate mediating the postsynaptic effects of PAR-1 at the NMJ, with the phosphorylation by PAR-1 negatively regulating the synaptic localization and function of Dlg21. Co-expression of Dlg-SA, which is no longer phosphorylated by PAR-1 and can protect against PAR-1-induced synaptic toxicity21, effectively blocked LKB1 overexpression-induced bouton loss (Fig. 4a). Dlg-WT also showed some protective effect, albeit weaker than Dlg-SA, whereas the phospho-mimetic Dlg-SD had no effect (Fig. 4a). LKB1 thus positively regulates PAR-1 at the postsynapse.

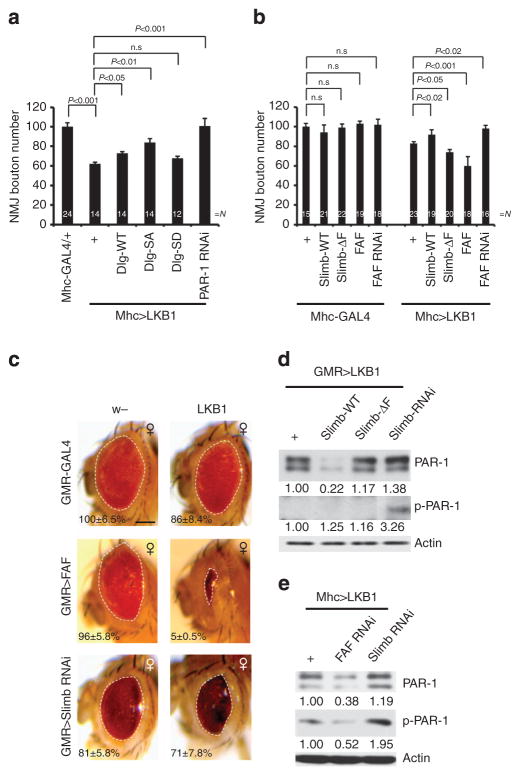

Figure 4. LKB1 cooperates with Slimb in the phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of PAR-1.

(a) Quantification of NMJ boutons showing genetic interaction between LKB1 and PAR-1 or Dlg. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (b) Quantification of NMJ bouton number showing genetic interaction between LKB1 and Slimb or FAF. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (c) Genetic interaction between LKB and FAF or Slimb in the retina in each of the indicated genotypes (GMR-Gal4/ +control, n =16; GMR-Gal4>UAS-LKB1, n =16; GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381, n =16; GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-LKB1, n =16; GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi, n =17; GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi +UAS-LKB1, n =17). Statistically significant differences are P<0.001 (GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381, GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-LKB1) or P<0.03 (GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi, GMR-Gal4>UAS-Slimb-RNAi +UAS-LKB1) as determined by Student’s t-test. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Dashed lines outline the eye contour. Values represent areas of retinal surface normalized with GMR-Gal4/ +control. Scale bar, 100 μm. (d,e) Western blot analyses showing the effects of LKB1 interaction with Slimb/ FAF on PAR-1 and p-PAR-1 levels in adult fly head extracts (d) or third instar larvae body-wall muscle extracts (e). Values represent normalized PAR-1 and p-PAR-1 levels. Actin serves as loading control. n.s, not significant.

We next tested possible functional interactions among LKB1, Slimb and FAF at the NMJ. The bouton-loss phenotype of LKB1 overexpression was effectively rescued by Slimb-WT or FAF-RNAi, but enhanced by Slimb-ΔF or FAF (Fig. 4b). We also tested the genetic interaction between LKB1 and Slimb in the retina. Although overexpression of LKB1 or Slimb-RNAi each resulted in slight roughness of the eye, their co-expression caused necrosis and a further reduction of eye size (Fig. 4c), supporting their genetic interaction. We also examined the relationship between LKB1 and FAF. The co-expression of LKB1 and FAF led to dramatically reduced eye size (Fig. 4c). Thus, LKB1 and FAF both positively regulate PAR-1, and the overexpression of FAF may enhance LKB1 overexpression effects through the stabilization of p-PAR-1 generated by LKB1.

To gather biochemical evidence that LKB1 and Slimb/FAF work cooperatively in a phospho-dependent ubiquitination and degradation mechanism to regulate PAR-1, we examined PAR-1 protein levels in animals co-expressing LKB1 and Slimb variants or FAF-RNAi. The co-expression of Slimb-WT or FAF-RNAi with LKB1 synergistically reduced endogenous PAR-1 and p-PAR-1 levels, whereas Slimb-RNAi had opposite effects (Fig. 4d,e), consistent with LKB1 and Slimb/FAF regulating phospho-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of PAR-1.

PAR-1 regulation has an impact on the synaptic toxicity of APP/Aβ-42

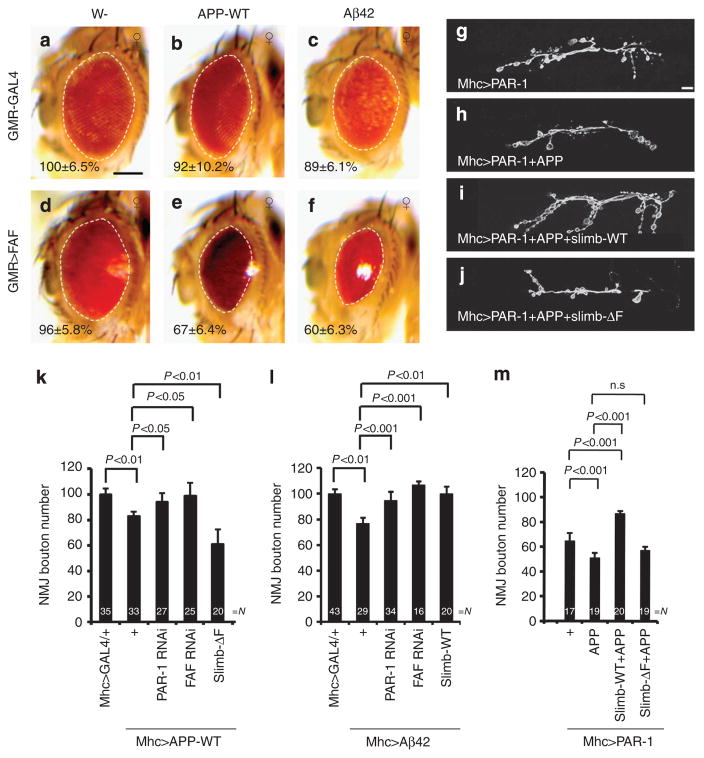

The LKB1/PAR-1 axis mediates the toxicity of APP in the retina10. We tested whether the phospho-dependent ubiquitination of PAR-1 regulated by SCF(Slimb) and FAF influences the toxicity of APP or Aβ-42. Overexpression of FAF had a mild effect, and WT human APP had no effect on eye size or morphology (Fig. 5b,d). However, their co-expression resulted in significant roughness and eye size reduction (Fig. 5e). Overexpression of Aβ-42 alone caused a slight roughness and eye size reduction, as reported26, but a significant enhancement was observed upon FAF co-expression (Fig. 5c,f). Thus, the PAR-1-deubiquitinating enzyme FAF influences the toxicity of APP/ Aβ-42 in the retina.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of PAR-1 mediates the toxicity of APP and Aβ–42.

(a–f) Genetic interaction between APP/Aβ-42 and FAF in the retina. Images of female flies are shown. All flies were grown at 25 °C. The genotypes are: GMR-Gal4/ +control (a), GMR-Gal4>UAS-APP-WT (b), GMR-Gal4>UAS-Aβ-42 (c), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 (d), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-APP-WT (e) and GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Aβ-42 (f) (n =16, 18, 16, 17, 16 and 16 animals, respectively). Statistically significant differences are P<0.01 (GMR-Gal4/ +control, GMR-Gal4>UAS-Aβ-42) or P<0.001 (GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381, GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-APP-WT; GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381, GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Aβ-42) as determined by Student’s t-test. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Dashed lines outline the eye contour. Values represent areas of retinal surface normalized with GMR-Gal4/ +control. Scale bar (a–f), 100 μm. (g–j) Representative anti-horseradish peroxidase immunostaining showing larval NMJ morphology of the following genotypes: Mhc-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 (g), Mhc-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 +UAS-APP-WT (h), Mhc-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 +UAS-APP-WT UAS-Slimb-WT (i) and Mhc-Gal4>UAS-PAR-1 +UAS-APP-WT +UAS-Slimb-ΔF (j). Scale bar, 10 μm. (k–m) Quantification of NMJ bouton numbers showing genetic interactions among APP, PAR-1, Slimb and FAF (k), among Aβ-42, PAR-1, Slimb and FAF (l), or between APP +PAR-1 and Slimb (m). Flies were grown at 29 °C (k) or 25 °C (l,m). N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. n.s, not significant.

AD is increasingly being recognized as a synaptic failure, and accumulating evidence implicates Aβ-42 in causing synaptic toxicity through a postsynaptic mechanism27,28. The potential postsynaptic toxicity of APP or Aβ-42 has not been established in Drosophila. We found that postsynaptic overexpression of APP or Aβ-42 at the NMJ caused ~ 20% reduction of bouton number (Supplementary Fig. S16). This effect was rescued by knocking down PAR-1 or FAF, but exacerbated by inhibiting Slimb via Slimb-ΔF (Fig. 5k). Similarly, overexpression of Aβ-42 postsynaptically also caused a reduction of bouton number, and this effect was rescued by Slim-WT, PAR-1-RNAi or FAF-RNAi (Fig. 5l).

PAR-1 exhibits enriched accumulation at the postsynaptic membrane of the NMJ synapses, where it critically regulates synapse morphology and function21. Postsynaptic co-expression of APP and PAR-1 caused a more severe loss of boutons (Fig. 5h,m), an effect rescued by co-expressing Slimb-WT but not Slimb-ΔF (Fig. 5i,j,m). Thus, regulation of PAR-1 by SCF(Slimb) critically mediates the toxicity of APP/Aβ-42 at the postsynapse.

Phospho-dtau mediates the postsynaptic toxicity of PAR-1

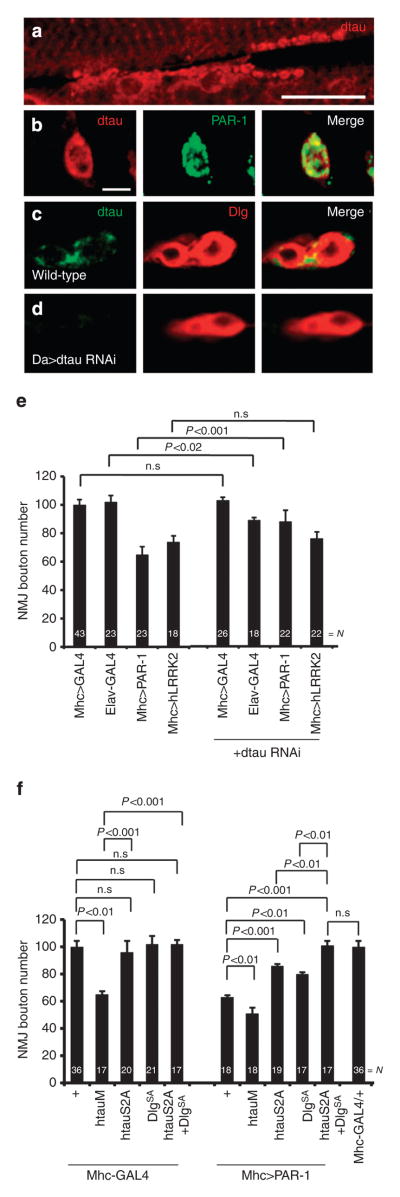

We were interested in understanding the mechanisms by which APP/Aβ-42 and PAR-1 exert postsynaptic toxicity. Recent studies in mammalian AD models have emphasized an important role of tau in mediating the cognitive effects of APP/Aβ28. Interestingly, an unexpected postsynaptic role of tau has emerged29,30. To test whether Drosophila tau (dtau) might mediate the postsynaptic toxicity of APP/Aβ-42, we tested whether it was expressed postsynaptically at the NMJ. Using a well-characterized dtau antibody31, we found that it was relatively enriched at the NMJ and co-localized with PAR-1 (Fig. 6a,b), which was predominantly localized to the postsynapse21, and Dlg (Fig. 6c), a known postsynaptic marker. This synaptic localization of dtau was eliminated in dtau-RNAi animals (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6. Phospho-dtau mediates the postsynaptic toxicity of PAR-1.

(a–d) Immunostaining showing dtau localization at third instar larval muscle and NMJ. (a) WT larvae stained with anti-dtau antibody shown in red. Scale bar, 50 μm. (b–d) Higher magnification images of NMJ boutons double-labelled with anti-dtau and anti-PAR-1 in WTanimals (b), or labelled with anti-dtau and anti-Dlg in WT (c) and Da-Gal4>dtau-RNAi animals (d). Scale bar, 5 μm. (e) Quantification of NMJ bouton number showing specific genetic interaction between PAR-1 and dtau, but not between hLRRK2 and dtau. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (f) Quantification of NMJ boutons showing mediation of the postsynaptic effects of PAR-1 by both Dlg and tau. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent means±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. n.s, not significant.

We next asked whether dtau might mediate the postsynaptic toxicity of PAR-1. The bouton-loss phenotype caused by postsynaptic PAR-1 was partially suppressed by dtau-RNAi (Fig. 6e). This effect was specific, as the bouton-loss phenotype caused by postsynaptic overexpression of LRRK2 (ref. 32) was not affected by dtau-RNAi (Fig. 6e). To test whether direct phosphorylation of dtau by PAR-1 might underlie their postsynaptic interaction, we used a non-phosphorylatable form of human tau with the PAR-1-target sites mutated (htauS2A)6. Like dtau-RNAi, htauS2A overexpression alone had no obvious effect on synapse morphology. However, its co-expression partially suppressed the effects of postsynaptic PAR-1 but not LRRK2 (Figs 6f and 7a). In comparison, h-tau R406W (htauM), a pathogenic form of tau associated with tauopathy, caused a severe bouton-loss phenotype when overexpressed alone (Fig. 6f), which was partially rescued by Slimb-WT or FAF-RNAi (Supplementary Fig. S17a), but exacerbated by PAR-1 co-expression (Fig. 6f).

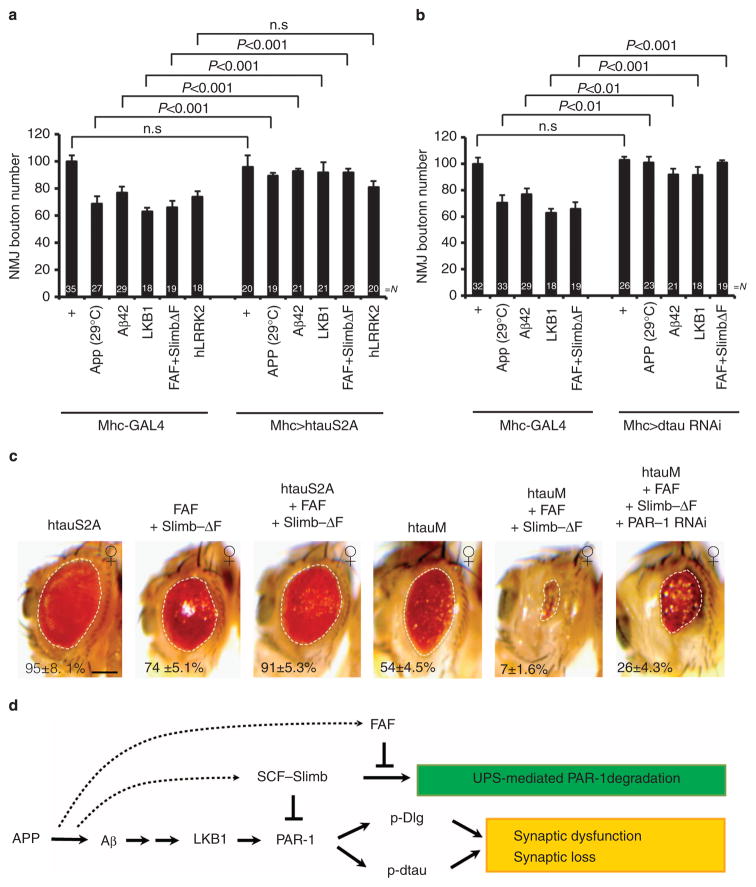

Figure 7. The dtau mediates the toxic effects of APP/Aβ-42 and the direct modifiers of PAR-1.

(a,b) Quantification of NMJ bouton number showing rescue by htauS2A (a) or dtau-RNAi (b) of the bouton-loss phenotypes induced by manipulations of the expression APP/Aβ–42 or the PAR-1 ubiquitination modifiers. N indicates the number of animals analysed. The error bars represent mean±s.e.m. P-values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test for each comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (c) Genetic interaction between tau and the modifiers of PAR-1 in the retina. Eye images of female flies are shown. All flies were grown at 22 °C. The genotypes are: GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauS2A (n =16), GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF (n =16), GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauS2A + FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF (n =17), GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM (n =17), GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM + FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF (n =18) and GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM +FAFEP381 + UAS-Slimb-ΔF +UAS-PAR-1-RNAi (n =18). Statistically significant differences are P<0.001 (GMR-Gal4>FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF, GMR-Gal4>htauS2A +FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF; GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM, GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM +FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF; GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM + FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF, GMR-Gal4>UAS-htauM +FAFEP381 +UAS-Slimb-ΔF +UAS-PAR-1-RNAi) as determined by Student’s t-test. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Dashed lines outline the eye contour. Values represent areas of retinal surface normalized with GMR-Gal4/ +control. Scale bar, 100 μm. (d) A model depicting the possible signalling pathways linking APP/Aβ–42 to synaptic dysfunction and synapse loss seen in AD. Dashed lines indicate potential direct regulations. n.s, not significant; UPS, Ubiquitin-proteasome system.

As mentioned earlier, Dlg was previously identified as a substrate of PAR-1 that mediates some of the effects of PAR-1 on postsynaptic morphology and function21. The incomplete rescue by Dlg-SA of PAR-1 overexpression-induced toxicity led to the proposal that there are other key synaptic targets of PAR-1 (ref. 21). To test whether both Dlg and dtau might function downstream of PAR-1 at the postsynapse, we co-expressed Dlg-SA and htauS2A in PAR-1-overexpression background. This resulted in a complete rescue of PAR-1-overexpression effect (Fig. 6f). Dlg and dtau seemed to act independently, as suggested by the inability of Dlg-WT or Dlg-SA to rescue the bouton-loss phenotype caused by htauM (Supplementary Fig. S17b). These results implicate both tau and Dlg as downstream effectors in mediating the postsynaptic effects of PAR-1.

PAR-1-dtau axis mediates the synaptic effects of APP/Aβ–42

We next tested the role of dtau in mediating the toxic effects of APP/Aβ-42 and the modifiers of PAR-1 identified above. The bouton-loss phenotypes caused by the postsynaptic overexpression of APP, LKB1 or the co-expression of FAF and Slimb-ΔF were all effectively suppressed by the co-expression of htauS2A (Fig. 7a) or dtau-RNAi (Fig. 7b). These results support that postsynaptic dtau, and in particular its phosphorylation by PAR-1, has a critical role in mediating the synaptic toxicity of APP/Aβ-42.

We also assessed the extent to which dtau might mediate the toxicity of APP/Aβ-42 and the modifiers of PAR-1 in the retina. The eye phenotype caused by FAF/Slimb-ΔF co-expression was significantly attenuated by added expression of htauS2A, but severely exacerbated by the addition of htauM (Fig. 7c). Moreover, the exacerbated toxicity caused by htauM and FAF/Slimb-ΔF synergy was partially relieved by PAR-1-RNAi, consistent with their genetic interaction requiring PAR-1-directed tau phosphorylation (Fig. 7c). At the biochemical level, we observed that, as reported before10, APP promoted tau phosphorylation at the PAR-1-target sites (Supplementary Fig. S17c). This effect was attenuated by Slimb-WT but enhanced by Slimb-ΔF (Supplementary Fig. S17c), supporting a critical role of SCF(Slimb)-mediated PAR-1 regulation in the induction of tau phosphorylation by APP. Together, these results support a key role of posttranslational PAR-1 regulation in modulating tau-mediated APP/Aβ-42 toxicity.

Discussion

Here we reveal a previous unknown mechanism of PAR-1 regulation in Drosophila that involves phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination and degradation. This mechanism targets the phosphorylated and activated forms of PAR-1 for ubiquitination and degradation. Using the Drosophila NMJ synapses and the retina as assay systems, we demonstrate that this newly identified mechanism of PAR-1 activity regulation is important for specifying synaptic morphology, such as bouton number, and neuronal survival, and is highly relevant to AD pathogenesis. It is anticipated that this regulatory mechanism may also be relevant to PAR-1/MARK function in other physiological or developmental contexts.

Our results show that active PAR-1 phosphorylated by LKB1 at the T408 site is normally present at a very low level. This could be due to a low basal phosphorylation of PAR-1 by LKB1, or that p-PAR-1 level is tightly regulated under physiological conditions. Our further studies support that p-PAR-1 is normally tightly controlled by SCF(Slimb) for ubiquitination and degradation, and that FAF antagonizes SCF(Slimb) action in this process. This conclusion was supported by comprehensive genetic and biochemical interaction and studies. Although SCF(Slimb) and FAF are both likely to have more than one substrates in vivo, which might contribute to some of the phenotypes observed in the genetic interaction studies (Supplementary Fig. S10), it is not clear how many targets are commonly regulated by them. The fact that PAR-1-RNAi could effectively rescue the synthetic effects between FAF and Slimb provided strong evidence that PAR-1 is a major mediator of their in vivo interaction. To our knowledge this is the first example of a common substrate regulated by SCF(Slimb) and FAF.

Ubiquitination represents one fundamental mechanism by which physiological and pathological signals may alter synapse structure and function33,34. The Drosophila NMJ synapses, which are glutamatergic in nature and possess well-defined pre- and postsynaptic compartments, provide a model system to understand mechanisms regulating synaptic differentiation and plasticity by ubiquitination and the contribution of synaptic dysfunction to AD pathogenesis. AD is increasingly being recognized as a synaptic failure35, and emerging data support postsynaptic toxicity as a key mechanism of APP/Aβ action. Interestingly, recent studies have focused attention on a pathogenic action of tau at the postsynaptic compartment as well28. The ability of Drosophila NMJ to recapitulate the postsynaptic toxicity of APP/Aβ and tau and to model their functional interaction thus establishes the NMJ as a powerful model system for elucidating the synaptic mechanisms of AD. Our studies placing the newly identified module of PAR-1 regulation in-between APP/Aβ and tau thus provide novel insights into the signalling mechanisms, underlying the postsynaptic toxicity of Aβ and tau. It is worth pointing out that the effects of both PAR-1 (ref. 21) and Slimb (this study) on NMJ synapses are primarily postsynaptic.

The positioning of SCF(Slimb) and FAF into the APP or Aβ/ LKB1/PAR-1/tau pathogenic pathway also raises the possibility that APP/Aβ or other disease-related signals may directly impinge on SCF(Slimb) or FAF to regulate their expression or activity (Fig. 7d). Previous studies showed that FAF has an important role in regulating synaptogenesis at the NMJ18, although its synaptic targets were largely unknown. FAF/USP9X exhibits dynamic expression patterns in the rodent brain, especially in the hippocampal regions relevant to AD36. If USP9X, like FAF, acts in a similar pathogenic cascade to regulate mammalian MARKs, its dynamic expression may contribute to region-specific vulnerability. USP9X is upregulated in the mouse brain with age37. This could contribute to the age-dependent effects of APP/Aβ on cognition and neuronal survival. Our results show that overexpression of FAF alone in the fly eye had a mild effect on eye morphology, whereas its overexpression in the muscle has no effect on NMJ morphology. Although this might be caused by different levels of FAF expression driven by different Gal4 drivers, or different sensitivities of eye and muscle to FAF activity, it is also possible that the activity of FAF or its interacting proteins are differentially regulated in a tissue-specific manner in flies.

Accumulating evidence strongly implicates PAR-1/MARKs as critical factors in AD. PAR-1/MARKs phosphorylate tau and associate with neurofibrillary tangles in AD4,38. PAR-1/MARK-mediated phosphorylation critically confers tau toxicity in fly and mammalian models6,39. Elevation of PAR-1/MARK-mediated tau phosphorylation was observed in AD40,41. Consistently, PAR-1/ MARK are activated by APP/Aβ in Drosophila or mammalian neurons10,39,42. Activated PAR-1 also directly phosphorylates the PSD-95 homologue Dlg, impairing its postsynaptic localization21. This may be mechanistically related to the synaptic PSD-95 defects seen in AD43,44. Interestingly, a recent genome-wide association study suggested a potential link of MARK4 to late-onset AD45. Our results support that phosphorylation of tau and Dlg/PSD-95 by PAR-1/MARK both contribute to AD-related synaptic toxicity39. Dlg/PSD-95 primarily acts as a scaffold molecule at the postsynapse46. The postsynaptic effect of tau, especially that of phospho-tau, is poorly understood. The fly NMJ offers a model system to dissect the mechanisms of phospho-tau toxicity at the postsynapse.

Methods

Fly strains

The UAS-PAR-1-WT, UAS-PAR-1-T408A, UAS-PAR–1-RNAi, UAS-LKB1-WT, UAS-LKB1-KD, UAS-LKB1 RNAi, UAS-Dlg-WT-GFP, UAS-Dlg-SA-GFP, UAS-Dlg-SD-GFP, UAS-htauM and UAS-htauS2A were described before10,21. UAS-HA-Ub was provided by Dr K Chung47, UAS-Slimb-WT by Dr F Rouyer48, UAS-LKB1-GFP by Dr D St Johnston49, UAS-Myc-Slimb-ΔF by Dr J Jiang50, UAS-Ago-WT and UAS-Ago-ΔF by Dr K Moberg25, UAS-Aβ-42 by Dr K Iijima-Ando26, UAS-CYLD20 by Dr X Tian, and faf BX4, faf F08 and hs-Myc-FAF by Dr J Fischer24. The Mhc-Gal4 driver was provided by Dr T Littleton. The UAS-FAF RNAi lines were obtained from Vienna Drosophila RNAi Centre. The FAF EP381, FAF EP3520, UAS-APP-WT, UAS-Slimb RNAi and GMR-Gal4 lines were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, third instar lavae were selected, dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Ted Pella) in PBS for about 15 min and washed 3 × in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The primary antibodies used were: anti-PAR-1 (1:10,000); anti-phospho-PAR-1 (1:1,000); anti-Slimb (1:1,000); anti-Dlg (4F3) (1:50, Hybridoma bank, University of Iowa); anti-GFP (1:8,000, Abcam); and anti-dtau (1:3). Primary antibody incubation was performed at 4 °C overnight. All secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) and Texas Red or FITC-conjugated anti-HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used at 1:200 and incubated for about 2 h at room temperature. Laval preparations were mounted in SlowFade Antifade kit (Invitrogen). Confocal images were collected from Leica confocal microscopes SP2 and SP5 equipped with an oil immersion objective (X40 HCX PL APO 1.25 or X100 HCX PL APO 1.46). Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence software was used to capture, process and analyse images. Analysis of the NMJ was performed essentially as described32. All crosses for genetic interaction studies in the NMJ were performed at 25 °C.

Transfection, IP and western blot analysis

Transfection of HEK 293T cells was performed using 1 μg pCDNA-PAR-1-WT-Myc or PAR-1-T408A construct. To generate the pCDNA-PAR-1-WT-Myc or pCDNA-PAR-1-T408A-Myc constructs, the corresponding cDNA inserts were cloned into the pCDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen).

For co-IP experiments, 70 mg frozen fly heads expressing UAS-PAR-1-WT-Myc or UAS-PAR-1-T408A-Myc transgene driven by GMR-Gal4 were collected. In the case of LKB1 IP, 50 third instar larvae of lkb1X5 mutant genotype or those expressing a UAS-LKB1-GFP transgene driven by Mhc-Gal4 were dissected. They were homogenized in IP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 60 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 10% glycerol, protease inhibitors and 50 μM MG132) and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were pre-cleared by incubation with protein G agarose (Pierce) for 1 h at 4 °C and then incubated with the indicated IP antibodies for 4 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with protein G agarose for 3 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed eight times with the IP buffer or PBS and boiled in SDS sample buffer. The samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis and western blot analysis.

For western blot analysis, the primary antibodies used were: anti-PAR-1 (1:8,000), anti-phospho-PAR-1 (1:1,000); anti-HA (1:2,000, Sigma); anti-Myc (1:1,000, Millipore); anti-GFP (1:2,000, Abcam); anti-Dlg (4F3) (1:1,000, Hybridoma bank, University of Iowa); 12E8 (1:8,000); anti-Actin (1:40,000, Sigma); and anti-Gapdh (1:3,000, Abcam).

In vivo ubiquitination assay

To perform the ubiquitination assay in vivo, 100 frozen fly heads of GMR-Gal4>PAR-1-WT-Myc +HA-Ubi or fafBX4/fafF08 genotypes were collected and homogenized in the IP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 60 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 10% glycerol and protease inhibitors) and centrifuged at 12,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was incubated with anti-PAR-1 or anti-p-PAR-1 antibody and then with protein G agarose or EZview Red Anti-c-Myc Affinity Gel (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. Beads were washed six times with PBS and boiled in SDS sample buffer.

In vitro deubiquitination assay

The p-PAR-1 proteins used as substrate were affinity purified from 50 mg frozen adult fly heads of GMR-Gal4>PAR-1-WT-Myc +HA-Ub genotype, using an anti-p-PAR-1 antibody. The FAF proteins used as the deubiquitinating enzyme were affinity purified with anti-Myc antibody from 50 mg hs-Myc-FAF fly heads collected after hs for 1 h at 37 °C and then stabilized for 2 h at 25 °C. To perform the in vitro deubiquitination assay, reactions were performed at 25 °C for 2 h in the deubiquitination buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ZnCl2 and 1 mM DTT). The reaction mixtures were stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer and boiled at 95–100 °C for 5 min, before subjected to western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

Fly eye sizes were measured on multiple samples (n>15) from both control and experimental genotypes using the NIH ImageJ software. Average eye size was presented as a normalized percentage of control eye size. We performed two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test to analyse the significance of differences between two groups. Quantification of NMJ bouton number was performed according to previously descried protocols (Lee et al., 2010 (ref. 32)). NMJ bouton number is normalized by muscle area at muscle 6/7 in abdominal segment A3. The experimental genotypes were normalized relative to the control genotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr G Rogers for the gift of the anti-Slimb antibody, Dr J Chung for anti-LKB1 antibody, Dr Peter Seubert for the 12E8 antibody. We also thank Drs F Rouyer, D Johnston, T Littleton, M Feany, K Chung, J Jiang, K Moberg, J Fischer, T Xu and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Centre and the Bloomington Stock Centre for providing fly stocks. We thank Jennifer Gaunce and George Silverio for their technical help. This study was supported by the McKnight Foundation (Brain Disorders Award), Alzheimer’s Association (IIRG0626723) and the NIH (R01AR054926, R01MH080378).

Footnotes

Author contributions

S.L., J-W.W. and B.L. designed the experiments and analysed the data. J.W. initiated the project and performed the initial genetic screen that identified FAF as a PAR-1 modifier. S.L. produced most of the data shown in the figures. B.L. and W.Y. generated some of the data shown in Fig. 1. S.L. and B.L. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matenia D, Mandelkow EM. The tau of MARK: a polarized view of the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurov J, Piwnica-Worms H. The Par-1/MARK family of protein kinases: from polarity to metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1966–1969. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.16.4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewes G, Ebneth A, Preuss U, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. MARK, a novel family of protein kinases that phosphorylate microtubule-associated proteins and trigger microtubule disruption. Cell. 1997;89:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trinczek B, Brajenovic M, Ebneth A, Drewes G. MARK4 is a novel microtubule-associated proteins/microtubule affinity-regulating kinase that binds to the cellular microtubule network and to centrosomes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5915–5923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishimura I, Yang Y, Lu B. PAR-1 kinase plays an initiator role in a temporally ordered phosphorylation process that confers tau toxicity in Drosophila. Cell. 2004;116:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timm T, et al. MARKK, a Ste20-like kinase, activates the polarity-inducing kinase MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J. 2003;22:5090–5101. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lizcano JM, et al. LKB1 is a master kinase that activates 13 kinases of the AMPK subfamily, including MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J. 2004;23:833–843. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang JW, Imai Y, Lu B. Activation of PAR-1 kinase and stimulation of tau phosphorylation by diverse signals require the tumor suppressor protein LKB1. J Neurosci. 2007;27:574–581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5094-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. Targeting proteins for destruction by the ubiquitin system: implications for human pathobiology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:73–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.051208.165340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang J. Regulation of Hh/Gli signaling by dual ubiquitin pathways. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2457–2463. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang J, Struhl G. Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature. 1998;391:493–496. doi: 10.1038/35154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winston JT, et al. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitinationin vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13:270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho MS, Ou C, Chan YR, Chien CT, Pi H. The utility F-box for protein destruction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1977–2000. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijman SM, et al. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiAntonio A, et al. Ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms regulate synaptic growth and function. Nature. 2001;412:449–452. doi: 10.1038/35086595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:77sr71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue L, et al. Tumor suppressor CYLD regulates JNK-induced cell death in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2007;13:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, et al. PAR-1 kinase phosphorylates Dlg and regulates its postsynaptic targeting at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 2007;53:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brajenovic M, Joberty G, Kuster B, Bouwmeester T, Drewes G. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human par protein complexes reveals an interconnected protein network. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12804–12811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Hakim AK, et al. Control of AMPK-related kinases by USP9X and atypical Lys(29)/Lys(33)-linked polyubiquitin chains. Biochem J. 2008;411:249–260. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Zhang B, Fischer JA. A specific protein substrate for a deubiquitinating enzyme: liquid facets is the substrate of fat facets. Genes Dev. 2002;16:289–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.961502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortimer NT, Moberg KH. The Drosophila F-box protein Archipelago controls levels of the trachealess transcription factor in the embryonic tracheal system. Dev Biol. 2007;312:560–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iijima K, Gatt A, Iijima-Ando K. Tau Ser262 phosphorylation is critical for Abeta42-induced tau toxicity in a transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2947–2957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ittner LM, Gotz J. Amyloid-beta and tau–a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ittner LM, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoover BR, et al. Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2010;68:1067–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidary G, Fortini ME. Identification and characterization of the Drosophila tau homolog. Mech Dev. 2001;108:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S, Liu HP, Lin WY, Guo H, Lu B. LRRK2 kinase regulates synaptic morphology through distinct substrates at the presynaptic and postsynaptic compartments of the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16959–16969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1807-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiAntonio A, Hicke L. Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the synapse. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:223–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi JJ, Ehlers MD. Emerging roles for ubiquitin and protein degradation in neuronal function. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:14–39. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Taya S, Kaibuchi K, Arnold AP. Spatially and temporally specific expression in mouse hippocampus of Usp9x, a ubiquitin-specific protease involved in synaptic development. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:47–55. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J. Age-related changes in Usp9x protein expression and DNA methylation in mouse brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;140:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chin JY, et al. Microtubule-affinity regulating kinase (MARK) is tightly associated with neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer brain: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:966–971. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.11.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu W, et al. A critical role for the PAR-1/MARK-tau axis in mediating the toxic effects of Abeta on synapses and dendritic spines. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;21:1384–1390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Augustinack JC, Schneider A, Mandelkow EM, Hyman BT. Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2002;103:26–35. doi: 10.1007/s004010100423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez M, et al. Characterization of a double (amyloid precursor protein-tau) transgenic: tau phosphorylation and aggregation. Neuroscience. 2005;130:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Abeta oligomers cause localized Ca(2 +) elevation, missorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, Tau phosphorylation, and destruction of microtubules and spines. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11938–11950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gylys KH, et al. Synaptic changes in Alzheimer’s disease: increased amyloid-beta and gliosis in surviving terminals is accompanied by decreased PSD-95 fluorescence. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1809–1817. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida CG, et al. Beta-amyloid accumulation in APP mutant neurons reduces PSD-95 and GluR1 in synapses. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seshadri S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2010;303:1832–1840. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:771–781. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee FK, et al. The role of ubiquitin linkages on alpha-synuclein induced-toxicity in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2009;110:208–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grima B, et al. The F-box protein slimb controls the levels of clock proteins period and timeless. Nature. 2002;420:178–182. doi: 10.1038/nature01122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.St Martin SG, Johnston D. A role for Drosophila LKB1 in anterior-posterior axis formation and epithelial polarity. Nature. 2003;421:379–384. doi: 10.1038/nature01296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ko HW, Jiang J, Edery I. Role for Slimb in the degradation of Drosophila period protein phosphorylated by doubletime. Nature. 2002;420:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nature01272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.