Abstract

This article uses data from the 1979 and 1997 cohorts of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth to estimate the proportions of young men and women who will take on a variety of partner and parent roles by age 30, as well as to describe how these estimates have changed across cohorts. It then draws from identity theory and related theoretical work to consider how the multiple family roles which young adults are likely to occupy—both over their life course and at a single point in time—may influence inter- and intra-family (unit) relationships in light of current trends in family complexity. This discussion highlights four key implications of identity theory as it relates to family complexity, and proposes several hypotheses for future empirical research to explore, such as the greater likelihood of role conflict in families with greater complexity and limited resources. Implications for public policy are also discussed.

As detailed in the preceding articles in this volume (Furstenberg; Manning, Brown and Stykes), complexity and instability are common family experiences. That is, families now occupy a range of diverse and fluid forms such that both adults and children are likely to transition into and out of multiple family configurations over time, as well as to be sequentially or simultaneously affiliated with more than one family ‘unit’ (or household) at various points in their lives. In addition to co-resident married relationships (with or without children), many adults will engage in cohabitation prior to or after having children, as well as non-resident and semi-resident (living together part of the time) romantic and parental relationships. Families comprising various combinations of married and unmarried, opposite- and same-sex partners, and biological and social (nonbiological) parents are also common, as are families that include full-, half-, and step-siblings, couples living together-apart or apart-together, adult children living with parents, and elder parents living with adult children. Shared physical and legal custody of children following parental union dissolution is also on the rise. Such diversity and fluidity in family forms means that adults and children are likely to take on multiple family roles, and that many children will be exposed to multiple types of parental figures, both simultaneously and over time. These demographic trends have important implications for social norms and family functioning vis-à-vis adults’ roles as partners and parents.

In this article, we first use data from the 1979 and 1997 cohorts of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) to describe the likelihood that young men and women will take on a variety of adult family roles by age 30. A complete accounting of all possible adult family roles is beyond the scope of our analyses and also precluded by limitations of currently-available data. Thus, we focus on a somewhat parsimonious set of common family roles, including resident cohabiting or married biological parent, nonresident biological parent following a marital or non-marital birth, and cohabiting or married resident social parent (unrelated co-resident partner or spouse of a biological parent). We also discuss how the chances that young adults will occupy particular family roles have changed across cohorts. Finally, we estimate the likelihood of young adults experiencing specific trajectories in family formation (union formation and first-time childbearing) by age 30. After describing these patterns, we draw from identity theory and related theoretical work to describe how the multiple family roles which adults are likely to occupy as partners and parents—both over their life course and at a single point in time—may influence inter- and intra-family (unit) relationships in light of current trends in family complexity. Finally, we present implications for future research and public policy.

Patterns of family complexity among young adults: Evidence from NLSY79 and NLSY97

Data and measures

We use parallel samples from two nationally-representative, longitudinal cohorts of the NLSY to estimate the cumulative proportion of young adults who experienced a variety of roles as partners and parents between ages 17 and 30.1 The NLSY97 sample consists of just under 9,000 young adults. The full NLSY79 sample consists of 12,686 young adults, but includes oversamples of poor, non-Hispanic whites and individuals in the military. We excluded these oversamples in order to enhance the comparability of the cohorts. As such, our NLSY79 analysis sample consisted of 9,763 young men and women.

At each interview, the NLSY collects information on whether respondents are married, cohabiting, or single (not living with a co-resident partner or spouse), have biological children in their household, have social children (the children of the respondent’s married or cohabiting partner) in their household, and have biological children living elsewhere (non-resident children).2 We combined these measures to document which respondents inhabited a series of specific roles in each survey wave. These roles included: single, married or cohabiting with resident biological children; single, married or cohabiting with resident social children; and single, married or cohabiting with non-resident biological children. We also constructed indicators for various combinations of parental roles that respondents may have experienced simultaneously and/or sequentially: having both resident biological children and non-resident biological children, having both resident biological children and resident social children, and having resident social children and non-resident biological children. Finally, we considered whether respondents simultaneously or sequentially experienced any combination of parental roles, and whether they simultaneously or sequentially experienced all three parental roles. In addition to these analyses based on the respondents’ household composition, we also conducted analyses based on respondents’ reports of the total number of live births they have had at each survey wave. This information, combined with their marital status at each wave, was used to estimate the proportion of young adults having marital, cohabiting, or single first births by age 30 and to distinguish important subgroups within each of these three categories.

Our analyses focused on estimating the proportion of respondents who experienced these roles at some point by age 30. To do so, we used Kaplan-Meier survival models, which account for the right-censoring in the NLSY97 data (not all respondents had reached age 30 by the most recent interview). We present estimates for the full sample, as well as separately for men and women. We also present some estimates separately by race/ethnicity (white, non-Hispanic and other; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic) and educational attainment (less than a high school education, a high school degree or GED, some college, and a bachelor’s degree or higher level of educational attainment by the most recent survey year).3 We present our results both graphically and in tabular form. All analyses were weighted to account for the complex sampling designs and attrition.

We emphasize that our estimates are relevant only to young adults (those ages 30 and under), and cannot be generalized to the full period of adulthood. This is important for two primary reasons. First, our estimates cannot be viewed as a comparison of whether men or women in a given cohort will ever occupy a particular role. For example, if some roles were simply postponed to later ages (after age 30) in the more recent cohort, then individuals would not yet have been observed in those roles, though they may be equally likely to hold them over the full course of adulthood. Second, it is well-established that less socioeconomically advantaged individuals begin family formation processes at younger ages than their more advantaged counterparts; they are also disproportionately likely to experience family complexity. Because our analyses extend only to age 30, they necessarily over-represent the family formation experiences of less advantaged individuals.

Results

Married, single, and cohabiting young adults with resident biological children

The cumulative proportion of young adults who had experienced each family type by age 30 is presented in Table 1, for the full sample and by respondent sex. Approximately 59 percent of the 1979 cohort and 54 percent of the 1997 cohort reported living with a biological child in at least one survey wave from ages 17-30. The data indicate that the likelihood that a young adult had been married and living with resident biological children by age 30 was considerably higher in the earlier cohort than the later cohort (51 percent vs. 36 percent). In contrast, the likelihood of cohabiting and living with resident biological children by age 30 was about three times as likely in the more recent cohort as the earlier cohort (24 percent vs. 8 percent). Having spent time as a single, resident parent by age 30 was also more common in the more recent cohort (21 percent vs. 15 percent).

Table 1.

Cumulative proportion of young adults ever experiencing particular roles by age 30

| Total | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| NLSY79 | NLSY97 | NLSY79 | NLSY97 | NLSY79 | NLSY97 | |

| Resident biological children | 58.7% | 53.9% | 50.0% | 45.3% | 67.4% | 62.9% |

| Single | 14.8% | 20.6% | 3.5% | 9.2% | 26.0% | 32.5% |

| Married | 51.4% | 36.1% | 45.5% | 30.5% | 57.3% | 41.9% |

| Cohabiting | 8.4% | 24.0% | 6.4% | 19.9% | 10.4% | 28.3% |

| Resident social children | 6.5% | 10.9% | 10.0% | 14.6% | 3.2% | 7.1% |

| Married | 5.9% | 5.2% | 8.9% | 6.2% | 3.0% | 4.3% |

| Cohabiting | <1% | 7.6% | 1.4% | 10.9% | <1% | 4.3% |

| Non-resident biological children | 12.5% | 16.1% | 18.8% | 23.6% | 6.2% | 8.4% |

| Single | 10.5% | 13.2% | 16.5% | 20.2% | 4.6% | 5.8% |

| Married | 4.1% | 5.1% | 5.7% | 6.9% | 2.6% | 3.2% |

| Cohabiting | 4.0% | 6.6% | 5.9% | 9.2% | 2.2% | 3.8% |

Note: Estimates are weighted proportions of young adults observed in a particular role (e.g, married with resident biological children) in at least one of the survey rounds by age 30. Please see text for additional details about the survival analyses used to derive these estimates.

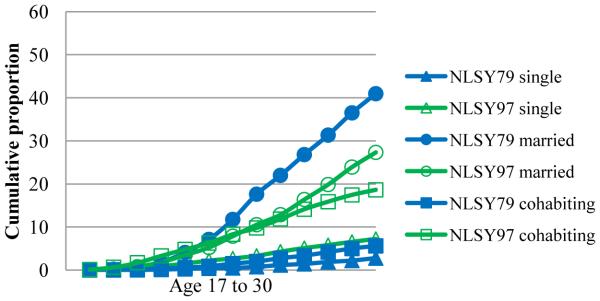

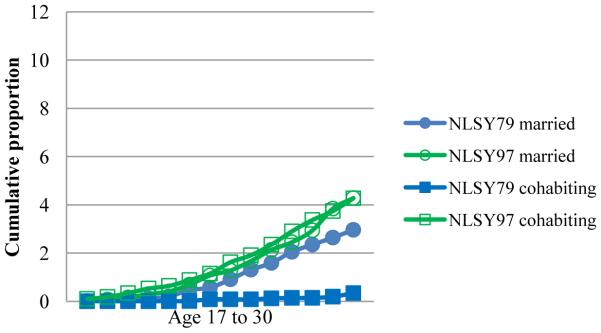

Figures 1a and 1b display the cumulative proportion of young adults between ages 17 and 30 who had biological children with whom they had co-resided, by sex and partnership type (estimates at age 30 are also presented in Table 1). In both cohorts, women were much more likely than men to have been a single (resident) parent by age 30. In the 1997 cohort, for example, 33 percent of women had this experience by age 30, compared with 9 percent of men. Gender differences for the other family roles were considerably smaller, though women were always more likely than men to have lived with their biological children, regardless of marital or cohabitation status.

Figure 1A.

Cumulative proportion ever living with resident biological children, Males

Figure 1B.

Cumulative proportion ever living with resident biological children, Females

Supplemental results regarding the sequencing of adult roles as partners and parents (not shown) also suggest a decrease in marriage and an increase in cohabitation over time—nearly half of the adults who had spent time as a single (resident) parent in the earlier cohort had previously been married (with resident children), compared to about one-quarter of those in the later cohort. In contrast, about 16 percent of adults in the earlier cohort had cohabited with a partner (and their joint biological child[ren]) prior to becoming a single parent, whereas this was true of 43 percent of young adults in the more recent cohort.

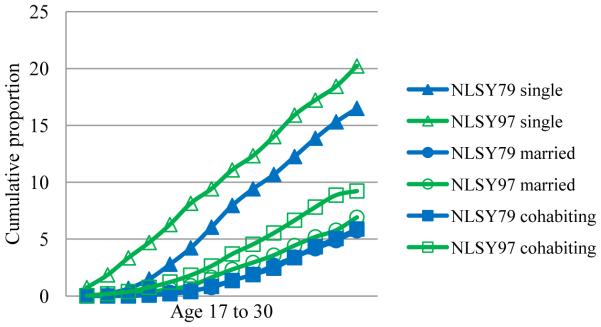

Married and cohabiting young adults with resident social children

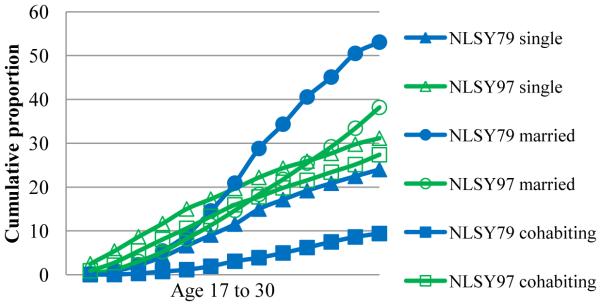

The cumulative proportion of young adults who lived with social children by age 30, by partnership type, is also shown in Table 1. Overall, approximately seven percent in the 1979 cohort and 11 percent in the 1997 cohort reported ever living with a social child between ages 17 and 30. The most striking finding here is the extremely small proportion (less than one percent) of 1979 cohort members who had lived with a cohabiting partner and that partner's children. This was a much more common experience for the more recent cohort (eight percent). For both cohorts, however, a greater proportion of men than women had experienced social parenthood by age 30. Figures 2a and 2b show the cumulative proportion of young adults who had ever lived with social children by each age (between 17 and 30), by sex and relationship status. The differences by sex are particularly striking in these figures. In both cohorts, men were substantially more likely than women to have lived with social children.

Figure 2A.

Cumulative proportion ever living with social children, Males

Figure 2B.

Cumulative proportion ever living with social children, Females

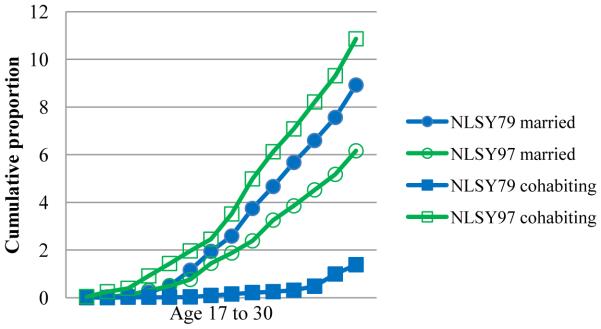

Married, single, and cohabiting young adults with non-resident biological children

Just under 13 percent in the 1979 cohort and approximately 16 percent in the 1997 cohort reported having non-resident biological children in one or more waves between ages 17-30. In both cohorts, a much larger proportion of men (17 percent and 20 percent for the 1979 and 1997 cohorts, respectively) than women (5 percent and 6 percent) had spent time as a non-resident biological parent by age 30 (Table 1). In addition, the likelihood of having spent time in a married or cohabiting relationship while simultaneously having non-resident children increased modestly between cohorts for both men and women, and this was particularly true with regard to cohabitation. Figures 3a and 3b show the cumulative proportion of young adults who had ever had non-resident biological children by each age (between 17 and 30), by sex and relationship status. The figures clearly indicate that, in both cohorts, it was much more common for young men than young women to have been a (single) non-resident parent by age 30.

Figure 3A.

Cumulative proportion with non-resident biological children, Males

Figure 3B.

Cumulative proportion with non-resident biological children, Females

In supplemental analyses (results not shown), we also examined the likelihood that members of the 1979 cohort had been a non-resident parent by age 50. We found that 32 percent of the sample had been a single, non-resident parent, 42 percent had been married and had non-resident children, and 14 percent had cohabited and had non-resident children at some point by age 50. It is important to consider that, as the respondents (and their children) age, it becomes increasingly likely that non-resident children will live independently. Nonetheless, given that the likelihood of having been a non-resident parent by age 30 was substantially higher, particularly for men, in the 1997 cohort than the 1979 cohort, a larger proportion of 1997 cohort members than 1979 cohort members can be expected experience non-resident parenthood by age 50.

Simultaneous and sequential parental roles

Table 2 presents the cumulative proportion of young adults who experienced multiple parental roles—sequentially and/or simultaneously—by age 30.4 Very few young adults in either cohort had experienced all three parental roles (resident biological parent, resident social parent, non-resident biological parent), either sequentially or simultaneously. Yet a sizeable proportion of young adults (particularly men) in both cohorts had experienced at least two such roles. Eight and twelve percent of young adults had simultaneously held two or more parental roles in the 1979 and 1997 cohorts, respectively. Thirteen and 18 percent had done so either sequentially or simultaneously. Most commonly, young adults in both cohorts experienced multiple parental roles consisting of having resident biological children as well as having either non-resident biological children or resident social children. In both cohorts, men were considerably more likely than women to experience multiple parental roles, largely because men were more likely to have experienced both nonresident and social parenthood.

Table 2.

Cumulative proportion of young adults experiencing more than one parental role by age 30

| Total | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| NLSY79 | NLSY97 | NLSY79 | NLSY97 | NLSY79 | NLSY97 | |

| Resident and non-resident biological children | ||||||

| Simultaneously | 4.4% | 7.0% | 5.3% | 8.4% | 3.6% | 5.5% |

| Simultaneously or sequentially | 9.9% | 13.2% | 14.0% | 18.2% | 5.9% | 8.0% |

| Resident biological and social children | ||||||

| Simultaneously | 4.0% | 6.6% | 5.6% | 8.7% | 2.5% | 4.4% |

| Simultaneously or sequentially | 4.7% | 7.8% | 6.8% | 10.3% | 2.6% | 5.3% |

| Resident social and non-resident biological children | ||||||

| Simultaneously | 1.2% | 2.4% | 2.3% | 4.1% | <1% | <1% |

| Simultaneously or sequentially | 2.0% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 6.8% | <1% | 1.1% |

| Any combination of at least two parental roles | ||||||

| Simultaneously | 8.3% | 12.4% | 10.8% | 15.0% | 5.9% | 9.7% |

| Simultaneously or sequentially | 13.2% | 18.2% | 18.2% | 23.5% | 8.3% | 12.7% |

| All three parental roles | ||||||

| Simultaneously | <1% | 1.2% | 1.0% | 2.0% | <1% | <1% |

| Simultaneously or sequentially | 1.7% | 3.4% | 3.2% | 5.9% | <1% | <1% |

Note: Estimates are weighted proportions of young adults observed in combinations of roles by age 30. Please see text for additional details about the survival analyses used to derive these estimates.

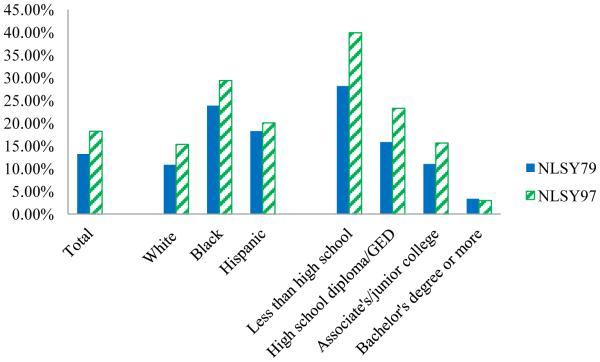

Figure 4 illustrates that experiencing multiple parental roles is more common for less educated and black and Hispanic young adults than for their more highly educated and white counterparts. Although these differences are apparent in both cohorts, experiencing multiple (sequential or simultaneous) parental roles has become increasingly common over time for all racial/ethnic groups and at all levels of educational attainment, with the exception of those with educational attainment of a bachelor’s degree or greater. For the 1997 (1979) cohort, approximately 40 (28) percent of young adults with less than a high school education had experienced at least two parental roles simultaneously or sequentially, compared with about 3 (3) percent for young adults with at least a bachelor’s degree. Experiencing multiple parental roles was most common for non-Hispanic black respondents: 29 (24) percent for the 1997 (1979) cohort, compared with 20 (18) percent for Hispanic and 15 (10) percent for non-Hispanic white respondents.

Figure 4.

Cumulative proportion ever simultaneously or sequentially experiencing more than one parental role

Sequencing of partnerships and first-time childbearing (family formation trajectories)

Table 3 presents estimates of the cumulative proportion of young adults who had experienced particular family formation trajectories (sequences of union formation and first-time childbearing) by age 30. Overall, the likelihood of having had a first birth by age 30 decreased for both men and women between the 1979 and 1997 cohorts. Sixty-seven percent of young adults in the 1979 cohort and 61 percent in the 1997 cohort had a first birth by age 30. In the 1979 (1997) cohort, 60 (56) percent of men and 75 (65) percent of women had a first birth by age 30.

Table 3.

Cumulative proportion of young adults experiencing particular union formation and first-time childbearing trajectories by age 30

| NLSY79 | NLSY97 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | |

|

|

||||||

| First birth by age 30 | 67.1 | 59.8 | 74.5 | 60.6 | 56.1 | 65.4 |

| First birth within marriage | 49.5 | 44.8 | 54.2 | 27.6 | 25.4 | 29.8 |

| Married at birth (without first cohabiting) | 43.1 | 39.0 | 47.2 | 17.2 | 16.8 | 17.7 |

| Cohabiting then married at birth | 6.4 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 12.1 |

| Married then birth then single in at least one post-birth survey wavea | 8.9 | 8.1 | 9.7 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| First birth within cohabitation | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 15.9 |

| Cohabiting at birth and remained cohabiting | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 5.4 |

| Cohabiting at birth then married (and remained married) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.7 |

| Cohabiting at birth then single in at least one post-birth survey wave | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.8 |

| First birth while single | 13.7 | 10.6 | 17.0 | 17.1 | 14.6 | 19.7 |

| Single at birth and remained single | 6.3 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 8.8 |

| Single at birth then cohabited but did not marry | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 6.0 |

| Single at birth then cohabited and then married | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.4 |

| Single at birth then married in later wave (without cohabiting first) | 4.9 | 3.7 | 6.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

Note: Estimates are weighted proportions of young adults experiencing the particular trajectories by age 30. Please see text for additional details about the survival analyses used to derive these estimates. In all cases, if a marriage or cohabitation was first observed in the same interview wave as the birth, we assumed that the birth occurred subsequent to (within the context of) that initiation of the marriage or cohabitation.

Universe includes all respondents with a first birth within marriage, except those in which the birth occurred at age 30.

Having had a first birth within a marriage was the most common family formation pattern for both men and women in each cohort. However, the prevalence of this type of family formation decreased substantially between cohorts. For example, 50 percent of all young adults (74 percent of those who had a first birth by age 30) in the 1979 cohort had a first birth within marriage; this was true for only 28 percent (45 percent) of those in the 1997 cohort. This change reflects two trends. First, relative to individuals in the 1979 cohort, those in the 1997 cohort tended to wait until they were older to have their first birth. Second, individuals in the 1997 cohort were more likely than those in the 1979 cohort to have had a non-marital first birth. Only 4 percent of young adults (6 percent of those who had a first birth by age 30) in the 1979 cohort had a first birth while cohabiting, whereas this was true for 16 percent (26 percent) of the 1997 cohort. In addition, whereas 14 percent of young adults (20 percent of those who had a first birth by age 30) in the 1979 cohort had a first birth while single (neither cohabiting nor married), this was true for 17 percent (28 percent) of the 1997 cohort.

The data also reveal several other trends over time with regard to the sequencing of partnerships and first-time childbearing among young adults. First, individuals in the 1997 cohort were considerably more likely than those in the 1979 cohort to have cohabited prior to marrying and (subsequently) having a first birth (10.3 percent vs. 6.4 percent). Second, those young adults in the 1997 cohort who had their first birth within marriage were considerably less likely than those in the 1979 cohort to subsequently separate or divorce (9 percent vs. 3 percent). Third, young adults in the 1979 cohort who had a first birth within cohabitation were more likely to subsequently break-up with their cohabiting partner than were those in the 1997 cohort. Roughly one-half of those in the 1979 who were cohabiting at the time of their first birth subsequently remained cohabiting or got married by age 30, whereas about onehalf had broken up. In contrast, roughly 60 percent of those in the 1997 cohort remained cohabiting or got married, whereas about 40 percent had broken up.

Summary

On the whole, these results demonstrate that young adults inhabit a variety of partner and parental roles during late adolescence and early adulthood. In some ways, the experiences of these two cohorts vary quite dramatically—in the proportion ever having been married with children versus cohabiting with children, and in the proportion having had a first birth in the context of cohabitation rather than marriage, for example, as well as in the probability of occupying multiple simultaneous or sequential parental roles, which has increased substantially over time. In other ways, however, their experiences by age 30 seem similar. Across both cohorts, we consistently find that young men are more likely than young women to inhabit multiple parental roles (both simultaneously and sequentially), and that rates of complexity are higher for lower-SES and racial/ethnic minority men and women. We next discuss how these demographic trends are related to theoretical conceptualizations of young adults’ identities and roles in the context of romantic relationships and parenthood.

Implications of identity theory for adults’ roles as partners and parents in a context of family complexity

Overview of identity theory

Identity theory is concerned with how individuals’ actions and interactions portray their self-concepts within and in relation to particular social structures, contexts, and situations; it is explicitly relational, interactional, and context-driven—rather than individual-centric—in nature (Burke and Stets 2009). As such, it is well-suited for considering systems of relationships and interactions among the various actors who take on multiple simultaneous and sequential roles in the context of family complexity.

Identities are the meanings that define individuals—to themselves and others—in their social roles. Individuals are thought to prioritize the many identities they occupy, both simultaneously and over the course of their lives, according to the degree of salience a particular identity has for them at a given point in time and in a given social context. This reflects that individuals function in multiple systems of interactions that may require different types of agency. Concurrent activation of multiple identities may engender identity role conflict (and related stress), both within and between individuals (Burke 1991; Burke and Stets 2009).

Identities evolve as a result of social interactions and feedback that comprise an ongoing process through which individuals attempt to create shared meaning vis-à-vis their social roles (Burke 1980, 2004; Burke and Stets 2009). In the identity theory literature, this process is referred to as identity verification. It generally requires that “‘all the parties involved… work together to create a context in which they can verify each other’s identities and have their own identity verified by the other’s identity” (Burke and Stets 2009, p. 152). As such, identity verification is both psychologically beneficial for individuals and also promotes and strengthens group bonds (Burke and Stets 1999). In contrast, consistent failure to achieve identity verification is associated with ongoing (dis)stress, anxiety, and internal conflict (Burke 1991, 1996, 2008). It is also inversely associated with self-esteem (self-efficacy/sense of competency, self-worth, and self-authenticity) (Cast and Burke 2002; Burke and Stets 1999). In response to identity conflicts, individuals may attempt to alleviate adverse emotions and achieve identity verification by altering their behaviors (Burke 2006; Burke and Stets 2009; Cast and Burke 2002). If they are unable to do so, they may abandon the identity-verification process, which may adversely influence their self-esteem and, in turn, their subsequent interactions and behaviors (Cast and Burke 2002; Burke and Stets 1999; Burke and Harrod 2005). Identity conflicts are particularly likely to arise as new identities are adopted. Furthermore, when multiple identities are enacted, verification of more salient identities will take precedence over verification of less salient identities (Stryker 1968).

Key implications of identity theory for adults’ roles as partners and parents

Below, we discuss four key implications of identity theory for adults’ roles as partners and parents in the context of family complexity. Throughout, we assume that transitions through adolescence and adulthood are typically marked by a series of dating relationships, some of which will eventually lead to cohabitation, marriage, and/or fertility, potentially followed by additional family transitions (break-ups and repartnerings) and ongoing fertility with the same or different partners.

Implication 1: There is likely to be greater congruity of identity meanings and less identity conflict in non-complex families and for individuals occupying only one family role than in complex families and for individuals occupying multiple family roles

Identity conflict occurs when identity-role meanings are incongruous within or between individuals. As such, family roles that are characterized by a clear set of obligations, responsibilities, and behavioral expectations should promote shared meaning among family members and induce less identity conflict than those that are ambiguously defined. This applies both to consistency among the meanings that different family members attach to a particular family role, and also to consistency among the meanings an individual attaches to the multiple family roles that she may simultaneously occupy.

With regard to adults’ roles as partners, the spousal role should engender greater individual and shared meaning than the cohabiting partner role, whereas both the spousal and the cohabiting partner role should engender greater meaning than the dating partner role. The legal, social, and public aspects (meanings) of marriage are well-established; thus, expectations regarding spousal obligations, responsibilities, and behaviors tend to be widely shared and function to encourage an “enforceable trust” (Cherlin 2004) between husband and wife. In contrast, cohabitation is less formally institutionalized; it is characterized by fewer normative and legal obligations and is less stable than marriage (Nock 1995). This lack of institutionalization is even more characteristic of dating relationships. In short, the extent to which a particular type of relationship is institutionalized—and, thereby, elicits mutual understanding and role expectations—is likely to be inversely associated with identity role conflict for the individuals involved.

Turning to adults’ roles as parents, identity conflict should be less common in non-complex families—those in which both biological parents are present in the household, are married to each other, and neither has children with another partner—than in complex families. First, parental role salience (commitment to parenting) is likely to be stronger for biological parents than social parents, given both institutional norms and evolutionary interests (see Berger et al. 2008; Berger & Langton 2011; Hofferth et al. 2013; Manning and Brown 2013; Scott et al. 2013). Second, as discussed above, marital ties are more heavily institutionalized than cohabiting ties. Third, marriage and childrearing often represent a “package deal,” especially for men (Townsend 2002). As such, spousal and parental roles—and the role identities, expectations, and behaviors of both mothers and fathers—are likely to correspond more closely in non-complex families than in complex families, thereby reducing the likelihood of identity conflict in the former (Stets and Cast 2007).

In general, identity conflict should increase with family complexity due to a greater likelihood of incongruity of role expectations. Conflict may occur, for example, if a resident biological mother and nonresident biological father attribute different meanings and expectations to the nonresident-father role. It may also occur if social parents and other family members, including children, attribute different meanings and expectations to the social parent role. In addition, nonresident- and social-parent roles may engender less role salience than resident- and biological-parent roles. Specifically, the biological parent identity may be more salient than that of social parent; likewise, resident parents may experience greater identity salience with the parental role than non-resident parents.

Identity conflict may be particularly likely to occur among disadvantaged families—which are disproportionately likely to be complex—given that resource constraints may pose barriers to meeting identity-role expectations. For example, to the extent that the identity associated with the (resident- or nonresident-, biological- or social-) father role encompasses that of breadwinner or economic provider, then disadvantaged men’s struggles to provide economic support may impede the identity verification process for these men and their (current or prior) partners and/or children. This, in turn, may adversely influence family functioning and relationships. At the same time, it is possible that identity roles differ for different population groups. For example, the extent to which the resident or nonresident, biological- or social-father role is defined by breadwinning and/or direct childrearing responsibilities (caregiving) may vary across population groups. If so, we might expect identity conflict associated with fulfillment of the father role to vary accordingly. Additionally, the circumstances under which individuals take on particular roles (such as “parent”) may vary by context. Burton and Hardaway (2012), for example, describe how many low-income mothers act in parenting roles as “other-mothers” to their networks of family and kin, but are hesitant to act in a parenting capacity when it comes to their romantic partners’ children with other women.

Adult members of complex families frequently occupy multiple family roles, both sequentially and simultaneously; this too may create opportunities for identity conflict. Families that extend across households require resources (time and money) to be allocated between households (Baxter 2012). This may cause internal conflict in deciding how to parse out such resources, as well as external conflict due to inconsistencies in the expectations of the individuals in each household. As such, it should be more difficult to achieve shared meanings and expectations across (multiple) family roles and, therefore, less likely that the range of individuals comprising a complex family will experience a sense of collective or shared identity than would be the case for those comprising a non-complex family. Again, this may be particularly true for families that face greater resource constraints.

An individual’s commitment to a particular identity is dependent on the salience of the identity to his sense of self, the satisfaction he achieves by enacting the identity, and his appraisal of himself in the role (his self-assessment of his performance in the role and his perception of how his performance is perceived by others). It is expressed through behaviors and resource investments that are consistent with social norms for that role (Fox and Bruce 2001). Cohabiting-partner, social-parent, and non-resident parent roles likely inspire less role salience than spousal, biological-parent, and resident-parent roles because the former entail less clear norms.5 Thus, individuals in complex families may experience less role satisfaction and develop poorer appraisals of themselves in their family roles than those in non-complex families. This may be especially true in a context of multiple-partner fertility in which there are even greater opportunities for incongruity in identity meanings. Fox and Bruce (2001, p. 396), for example, describe the father identity as being “one of varying salience, dependent on choice and circumstance.” In their empirical work, they hypothesize that the salience of the father identity will be a key predictor of fathers’ role performance; consistent with this hypothesis, they find greater role salience, greater role satisfaction, and positive self-appraisals of performance in the role to be associated with higher quality parenting attitudes and behaviors among biological fathers.

These ideas can be applied to adult roles as partners and parents more generally. That is, the salience of a particular partner or parent identity to an individual should be positively associated with both the likelihood that the individual will exhibit ongoing behaviors that are consistent with that role and the satisfaction he will achieve from successfully performing it. Such behaviors should, in turn, reduce ongoing identity conflict. In contrast, if an individual has difficulty enacting a high salience identity role, or encounters identity conflict with regard to that role, he may experience considerable dissatisfaction and psychological discomfort. In response, he might discontinue behaviors that are consistent with the identity he associates with the role, or disengage from the role entirely. Such actions may pose a barrier to future identity verification. In a recent study of low-income fathers, Edin and Nelson (2013), for instance, describe how many of these men experience considerable tension between wanting to forge a strong attachment to their (new) children and being unwilling or unable to meet the children’s mothers’ expectations for them as fathers and partners, which may result in a range of negative consequences. Indeed, the authors conclude that “[w]hen fathers are far more sure of their commitments to a child than to the mother of that child—when they tell themselves, as they often do, that their relationship with the child ought to have nothing to do with their relationship to that child’s mother—they are even less willing to do what it takes to turn their lives around” (p.206).

Implication 2: Transitions in family configuration necessitate changes in identities and associated adjustments in identity roles

Identities vary in terms of their salience (in a given situation) as well as by the particular situations in which they are enacted (Stets and Cast 2007). As relationships and family configurations change—for example, as adults progress from dating to cohabitation or from either of these relationships to marriage, have a child together, or dissolve their dating, cohabiting, or marital relationship (within or outside of the context of children)—family members necessarily take on new role identities that they will seek to verify. Identity conflicts may both lead to and result from family configuration transitions (Stets and Cast 2007). For example, identity conflict vis-à-vis individuals’ roles as partners and parents is associated with subsequent union dissolution (Cast and Burke 2002) which, in turn, requires enactment of new identity roles, as the couple transitions out of its romantic relationship and each member (potentially) repartners and/or experiences new-partner fertility. Union dissolution is particularly complicated when (joint biological) children are involved. In such situations, the mother and father must revise their parental identities vis-à-vis one another and establish new roles with regard to their division of caregiving and decision making responsibilities, as well as the provision of material resources for the child(ren).

Beyond requiring individuals to take on new family roles, transitions in family configuration are also likely to trigger changes in the salience of existing identities. For example, the birth of a child necessitates a transformation of both the mother’s and father’s roles as partners, as well as the initiation of their new roles as parents (Burke and Stets 2009; Habib 2012). The salience of the parent identity for each parent, the level of consistency between the parental identity and other identities (including that of partner or spouse and resident or nonresident parent to other children), and the level of consistency between their expectations vis-à-vis the parental identity are likely to affect how the transition influences them individually and in relation to one another (Habib 2012). Additionally, having a child with a new partner may alter the salience of (commitment to) the non-resident parent identity with regard to a former child.

Implication 3: Identity verification should be more difficult in complex families than non-complex families

Individuals attempt to maintain and confirm their self-perceptions with regard to particular identity roles using strategies that may ultimately encourage or discourage current or future identity verification (Stets and Cast 2007). For example, avoiding or expressing hostility toward an ex-partner in response to identity conflict may inhibit future identity verification in the role of non-resident co-parent. It may also adversely influence identity verification with non-resident children, particularly if it leads to decreased contact with them. On the other hand, strategies such as revising one’s identity meaning to be better aligned with the ex-partner’s expectations may aid identity verification in that particular relationship. Doing so may, however, have implications for identity verification in other relationships, such as that with a current partner or spouse. To the extent that individuals inhabit multiple identities at the same time, the probability of verifying all identities across all relationships becomes considerably smaller. For example, a non-resident parent may downgrade his parental role vis-à-vis a non-resident child as a way of prioritizing his current partner and children, perhaps because he feels a stronger sense of membership in the current family unit than the prior one (it is unclear, however, whether this is likely to hold when the current family unit includes only social children, as opposed to any biological children). These ideas are consistent with “package deal,” “competing obligations,” and “resource dilution” theories that have been applied to (particularly men’s) parenting in complex families (Scott et al. 2013; Townsend 2002). Such a strategy may decrease identity conflict and thereby increase the likelihood of identity verification in the new family unit. At the same time, it is likely to increase identity conflict with the ex-partner and non-resident child(ren).

Because identity meanings and associated expectations are likely to be less congruous among individuals in complex families than those in non-complex families, the complexity of family configuration should be inversely associated with identity verification. As such, individuals in complex families will likely experience less satisfaction in (at least some of) their family roles and, perhaps, poorer self-appraisals in those roles. Over time, this may manifest in behaviors that are inconsistent with social norms for the role, thus creating further conflict (Fox and Bruce 2001) in an ongoing cycle. Empirical research suggests, for example, that new-partner fertility is associated with a shifting of investments from initial families to new families, as well as with decreased cooperative parenting between resident and non-resident parents (Berger, Cancian, and Meyer 2012; Tach, Mincy, and Edin 2010). In turn, a parent’s behaviors toward their (non-resident) children may heavily depend on the quality of their relationship with the other parent and the extent to which they are able to achieve mutual identity verification. Existing evidence suggests that higher quality relationships between resident and non-resident parents are associated with higher quality parenting by non-resident parents (Carlson, McLanahan, and Brooks-Gunn 2008).

Identity conflict may be particularly likely in the context of multiple-partner fertility, both because family membership is less well-defined, and because the individuals involved face competing demands from multiple family units. That is, family members are faced with the difficult task of balancing their commitment to a particular identity (e.g., resident biological father, nonresident biological father, resident social father) with their commitment to a particular family unit or relationship (e.g., current or prior family units; particular mothers and the biological or social, resident or nonresident children associated with them). This has the potential to disrupt or prevent identity verification and, in some cases, individuals may choose to de-prioritize or even give up particular identity roles. Edin and Nelson (2013), for example, use the term “serial fatherhood” to describe the process through which unwed fathers, who were unsuccessful in previous relationships with their children’s mothers and the children themselves, substitute relationships with new partners (and children) as a means of coping with unsuccessful past attempts at being a “good” father.

Implication 4: Difficulty achieving identity verification implies that complex families will exhibit greater psychological discomfort and poorer family functioning than non-complex families

Identity verification helps individuals “feel understood and accepted in the[ir] relationship[s]… [which] should serve as an incentive for social actors to increase taking the role of the other” or expressing empathy with others in their joint social roles (Stets and Cast 2007, p.526). When identity conflict occurs, individuals are likely to feel that they lack control over their social situations and thus to experience low self-esteem and self-efficacy; such psychological discomfort may give way to negative emotional responses, including lack of empathy, increased aggressiveness, and controlling behaviors (Stets and Burke 2005a). Empathy, trust, and being liked by one’s spouse are positively associated with identity verification within marriage (Stets and Cast 2007). Adults also report better relationship quality and greater marital satisfaction when their partner or spouse reinforces their own self-perceptions (Burke and Stets 1999). Identity conflict, on the other hand, is associated with poorer relationship quality (Stets and Burke 2005a), a greater probability of union dissolution (Cast and Burke 2002), less self-worth and self-efficacy, and more anger, depression and (dis)stress (Stets and Burke 2005b).

Turning to adults’ roles as parents, one's commitment to children is thought to be a function of the salience of the parental role, the parent’s sense of self, the satisfaction the parent feels when activating that role, and the perception that others view the parent as performing the role well. This implies that ongoing commitment to the parental role is, at least in part, dependent on one’s relationship with the other parent and the extent to which family members are able to achieve (mutual) identity verification, whether or not the parents are co-resident (Fox and Bruce 2001). Prior research has found the transition to parenthood to be associated with both positive and negative changes in adult mental health, self-concept, self-esteem, stress, and anxiety; on average, child birth also tends to have a negative influence on relationship satisfaction and the couple’s relationship quality (Habib 2012). However, couples engaged in higher-quality relationships and those that were more satisfied with their relationship prior to the birth—each of which implies a greater degree of identity verification—tend to experience smoother transitions into parenthood than other couples (Habib 2012). For fathers, research suggests that the perceived salience of the parental or ‘fathering’ role, the extent to which a father believes he is successfully fulfilling the role, and the quality of his relationship with the mother are all positively correlated with his behaviors toward and involvement with children (Habib 2012). A father’s performance in these areas is, in turn, likely to influence the quality of his relationship with the mother and the likelihood that they achieve ongoing identity verification.

Additionally, Research by Tsushima and Burke (1999) suggests that mothers who fail to achieve identity verification in the parental role (experience problems with behavioral control and have frequent confrontations with their children) may become frustrated and respond by distancing themselves from their children and providing less adequate supervision and care. This is particularly likely to occur among mothers who perceive the parental role as predominantly oriented toward behavioral control. Engaging in less effective parenting behaviors may, in turn, lead to further frustration and stress, and ultimately less self-efficacy and self-esteem in the parental role. In contrast, mothers whose parental roles are guided by higher-level principles for childrearing, rather than behavioral control, tend to engage in more efficient parenting strategies (more role modeling and less disciplinary actions) and realize greater identity verification in the parental role. They also tend to exhibit more empathy with their children, which may facilitate mutual identity verification and decrease parent-child conflict and adverse emotions. This may lead to increased self-efficacy and self-esteem for both children and parents (Tsushima and Burke 1999). Though not tested by Tsushima and Burke, these concepts may apply to fathers as well.

In sum, because identity verification is associated with psychological functioning, as well as ongoing behaviors and relationship quality, lower levels of identity verification in complex families are likely to be associated with poorer individual and family functioning. This may (adversely) influence future identity-role behaviors and the wellbeing of both parents and children. Furthermore, although we are aware of no empirical research to explicitly test this hypothesis, it is possible that difficulty achieving identity verification among individuals (e.g., resident and non-resident parents) in complex families may directly lead some adults to distance themselves from their ex-partners and non-resident children.

Implications for future research and public policy

Our empirical work examined the frequency with which young adults in the NLSY 1979 and 1997 cohorts experienced a variety of family roles as partners and parents, as well as the extent to which they experienced these roles sequentially or simultaneously. We found that the complexity of adult family roles has increased over time. By age thirty, for example, approximately eight percent of young adults in the 1979 cohort and 12 percent of the young adults in the 1997 cohort had experienced at least two parental roles simultaneously in one or more of survey years. Having had both resident and non-resident biological children as well as resident biological children and resident social children were the most common combinations of parental roles experienced by young adults. The partner and parent roles taken on by these young adults ranged broadly, from single parent with resident biological children to cohabiting parent with social children. In part, increases in family complexity over time may reflect differences in family formation patterns between cohorts. It is well known that the average age at first birth has increased over time; likewise, the proportion of first births that occur outside of marriage (and particularly those occurring in the context of cohabitation) has also increased over time, particularly among less advantaged individuals. At the same time, however, our results indicate that there have been increases (of varying magnitude) over time in the proportion of young adults inhabiting more than one parental role simultaneously, and this trend was present for all of the educational and racial groups we considered, except those with a college degree or more education. Finally, although we found some evidence of greater relationships stability for couples in the 1997 cohort that had a first birth within the context of cohabitation (relative to marriage), as compared to those in the 1979 cohort who had a birth while cohabiting, cohabiting relationships continue to be considerably more likely to dissolve than marriages.

Despite these trends, most existing empirical work does not account for the full range of partner and parental roles an adult may simultaneously occupy or may have occupied over time, nor investigate how these experiences may influence the individual’s identity meaning, performance, and behaviors in these roles. Studies tend to focus on a specific role (resident or non-resident biological parent, married or cohabiting social parent,) an individual occupies with regard to a particular partner, child, or family unit. Whereas existing work sometimes adjusts for whether an individual also occupies another role (often by controlling for whether she has children with another partner), few if any studies explicitly examine how a range of partner and parent behaviors may be influenced by simultaneously engaging multiple family roles within or across family units. This area of analysis is ripe for inquiry.

In addition, we are aware of no study to empirically test partner or parent identity verification in the context of family complexity. Given that identity verification may have important consequences for individual and family functioning, future research would be well-served by taking this on. Future work should examine whether and how multiple sequential and simultaneous family roles may be associated with identity verification and, more broadly, family relationships and parental behaviors. It should also address whether there are subgroups of the population that are more (less) likely to struggle with identity verification in the context of family complexity, as well as whether specific family configurations and roles are particularly subject to identity-role conflict and problems with identity verification. Finally, future research should explicitly examine associations between identity verification and adult, child, and family functioning and wellbeing. For instance, future work should investigate whether lack of identity verification (and associated conflict) helps explain why cohabiting relationship are less stable than marriages, and why subsequent marriages are more likely to dissolve than initial marriages. It should also examine whether identity conflict and verification problems are associated with parenting behaviors and satisfaction with interpersonal interactions across family configurations.

Our work also suggests that family policies must now balance a wide range of actors, roles, and relationships within and across families. It is unrealistic for policies to focus primarily on (coresident and non-coresident) biological parents and their joint child(ren). Our application of identity theory to family complexity suggests that families may be less likely to function—economically and socially—as cohesive units than has been the case in the past, and than most existing policies assume. This implies a substantial shift in how policies should approach families and family functioning, as well as familial roles, obligations, and responsibilities. It is relevant to any policy that links eligibility or benefit levels to family unit membership. Given high rates of cohabitation, for example, the role of domestic partner benefits and ‘common law marriage’ policies may become increasingly important for both same- and different-sex couples with and without children. Pension and survivors’ benefits are generally only available to married spouses and widow(er)s. Likewise, cohabiting partners are unlikely to receive spousal support after a break-up (although there are some exceptions). In addition, parental leave and health care coverage in the United States, particularly when employer provided, often do not apply to a cohabiting partner’s children. Even with the implementation of mandated health care coverage, questions remain as to which parent’s policy should (or must) cover which children, and this may vary by co-resident, marital, and biological status. Likewise, tax credits, cash transfers, food and nutrition programs, and child support policies must all grapple with family complexity and multiple-partner fertility, a weighty task given that these programs were designed for simpler family configurations, which were assumed to be relatively static (rather than fluid) in nature. As such, child-conditioned benefits must often be assigned to one particular family unit or household such that frequently children can only be ‘claimed’ in one household, regardless of their actual living situation or time spent in various households.

The children associated with complex families tend to be socioeconomically disadvantaged, and the inverse relation between socioeconomic disadvantage and child wellbeing is well-established. To the extent that family complexity is also associated with less effective parenting, as well as lower levels of parental wellbeing—potentially due to identity verification problems—we may expect adverse effects on child wellbeing to be exacerbated. This, too, has implications regarding ongoing intergenerational transfer of parenting behaviors and social inequality, and potential policy efforts to improve child outcomes in economically disadvantaged families.

In short, policy must grapple with different patterns of biological, marital, and coresidential ties, as well as with which types of ties to privilege in what circumstances. It must also consider the needs, capabilities, and wellbeing of biological, social, resident, and non-resident parents and the children with whom they are associated. Furthermore, it must account for the fact that these relationships are (increasingly) fluid over time and that individuals are (increasingly) likely to occupy multiple of these roles simultaneously. Many existing policies are targeted at particular categories of families. Yet high rates of complexity make it difficult to categorize families, and to develop appropriate policies for promoting child and family wellbeing. Policy choices must also balance conflicting principles and inevitable trade-offs in issues of equity, adequacy, affordability, and outcomes from multiple perspectives, as well as simplicity of implementation and administration versus the ability to tailor interventions to the specific needs associated with (evolving) family configurations. Increasing family complexity also has implications regarding administrative capacity and feasibility of policy and program implementation and ongoing operation across a range of policy domains. These issues are addressed in a subsequent article in this issue (e.g., Lopoo and Raissian).

Acknowledgments

Note: This research was supported by NICHD grant number K01HD054421 (to Berger), as well as by funding from the Institute for Research on Poverty and the Waisman Center (NICHD grant number P30 HD03352) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Footnotes

We began our analyses at age 17 because this was when the relevant measures (particularly in the 1997 cohort) began to be collected for all respondents.

The variables used to measure non-resident children were slightly different across the two cohorts. For the 1979 cohort, respondents reported where each biological child “usually” resided, and those who usually resided outside the respondent’s household (with the exception of those away at school) were considered non-resident. For the 1997 cohort, we used a pre-constructed measure of the number of non-resident biological children the respondent had at each survey wave. The handling of adopted children also differs across surveys. In 1997, adopted children are categorized with biological children. In the 1979 cohort, however, adopted children are indistinguishable from step-children. This may make a difference for the segment of the adopted population of children that were adopted by both, rather than one of their parents. In addition, because information about biological children’s usual place of residence was not available between 1979 and 1981 or in the 1983 survey, we exclude those interview years from our analyses.

For the 1979 cohort, data were available about the highest degree obtained for all survey years beginning with 1988. For the years prior to that, we base our measure of education on the total number of years of school completed, with >12 years coded as no high school, 12 years considered a high school diploma/GED, 13-15 years coded as a “some college”, and 16 or more years coded as a bachelor’s degree or more. Note that the recoding based on years of education was only relevant for the relatively few respondents who did not have more recent education information available from the 1988 and later survey years.

Note that our analyses estimate the number of types of roles young adults inhabit. An individual who has non-resident children from two relationships, for example, would be counted as experiencing multiple roles if he also had resident biological or resident social children. In contrast, if he only had non-resident biological children, he would not be counted as experiencing multiple roles, even if he had non-resident children with multiple partners. In this way, we underestimate the level of complexity experienced by the young adults in the sample.

As these roles become more common, however, new norms and related role expectations may evolve and change. Thus, it is possible that the degree of identity-conflict associated with particular sequential or simultaneous roles may change over time, or vary between subgroups of the population in which particular family configurations are more or less common.

Contributor Information

Lawrence M. Berger, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Sharon H. Bzostek, Rutgers University

References

- Baxter Jennifer A. Fathering across families: How father involvement varies for children when their father has children living elsewhere. Journal of Family Studies. 2012;18:187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Lawrence M., Cancian Maria, Meyer Daniel R. Maternal re-partnering and new-partner fertility: Associations with non-resident father investments in children. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Lawrence M., Carlson Marcia J., Bzostek Sharon H., Osborne Cynthia. Parenting practices of resident fathers: The role of marital and biological ties. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:625–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Lawrence M., Langton Callie. Young disadvantaged men as fathers. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2011;635:56–75. doi: 10.1177/0002716210393648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J. The self: Measurement requirements from an interactionist perspective. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1980;43:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J. Identity processes and social stress. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:836–849. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J. Social identities and psychosocial stress. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial stress: Perspectives on structure, theory, life-course, and methods. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J. Identities and social structure: The 2003 Cooley-Mead Award address. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J. Identity, social status, and emotion. In: Clay-Warner J, Robinson DT, editors. Social structure and emotion. Elsevier; San Diego: 2008. pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J., Harrod Michael M. Too much of a good thing? Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005;68:359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J., Stets Jan E. Trust and commitment through self-verification. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1999;62:347–360. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J., Stets Jan E. Identity Theory. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burton Linda M., Hardaway Cecily R. Low-income mothers as “othermothers” to their romantic partners’ children: Women’s coparenting in multiple partner fertility relationships. Family Process. 2012;51:343–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., McLanahan Sara S., Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Coparenting and nonresident fathers’ involvement with young children. Demography. 2008;45:461–488. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cast Alicia D., Burke Peter J. A theory of self-esteem. Social Forces. 2002;80:1041–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. The deinstitutionalization of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:848–861. [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, Nelson Timothy J. Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fox Greer L., Bruce Carol. Conditional fatherhood: Identity theory and parental investment theory as alternative sources of explanation of fathering. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:394–403. [Google Scholar]

- Habib Cherine. The transition to fatherhood: A literature review exploring paternal involvement with identity theory. Journal of Family Studies. 2012;18:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth Sandra L., Pleck Joseph H., Goldscheider Frances, Curtin Sally, Hrapczynski Katie. Family structure and men’s motivation for parenthood in the United States. In: Cabrera Natasha J., Tamis-LeMonda Catherine S., editors. Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Routledge; New York: 2013. pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D., Brown Susan L. Cohabiting fathers. In: Cabrera Natasha J., Tamis-LeMonda Catherine S., editors. Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Routledge; New York: 2013. pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Nock Steven L. A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 1995;16:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Mindy E., Peterson Kristen, Ikramullah Erum, Manlove Jennifer. Multiple partner fertility among unmarried nonresident fathers. In: Cabrera Natasha J., Tamis-LeMonda Catherine S., editors. Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Routledge; New York: 2013. pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Stets Jan E., Burke Peter J. Identity verification, control, and aggression in marriage. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005a;68:160–178. [Google Scholar]

- Stets Jan E., Burke Peter J. New directions in identity control theory. Advances in Group Processes. 2005b;22:43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stets Jan E., Cast Alicia D. Resources and identity verification from an identity theory perspective. Sociological Perspectives. 2007;50:517–543. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker Sheldon. Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1968;30:558–564. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker Sheldon. Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Benjamin Cummings; Menlo Park, CA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tach Laura, Mincy Ronald, Edin Katherine. Parenting as a ‘package deal’: Relationships, fertility and nonresident father involvement among unmarried parents. Demography. 2010;47:181–204. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend Nicholas W. The package deal: Marriage, work, and fatherhood in men’s lives. Temple University Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima T, Burke Peter J. Levels, agency and control in the parent identity. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1999;62:173–189. [Google Scholar]