Abstract

Prostate biopsies are usually performed by urologists in the office setting using transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guidance. The current standard of care involves obtaining 10–14 cores from different anatomical sections. These biopsies are usually not directed into a specific lesion as most prostate cancers are not visible on TRUS. Color-Doppler, ultrasound contrast agents, elastography, MRI, and MRI/ultrasound fusion are proposed as imaging methods to guide prostate biopsies. Prostate MRI and fusion biopsy create opportunities for diagnostic and interventional radiologists to play an increasingly important role in the screening, evaluation, diagnosis, targeted biopsy, surveillance and focal therapy of the prostate cancer patient.

Introduction

Indications for prostate biopsy include a positive digital rectal exam (focal nodule, stiffness, or asymmetry), clinical symptoms, high serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) or PSA velocity (increase in PSA per year), and to monitor known cancers for transformation to a more aggressive phenotype. The standard of care involves obtaining 10 – 14 cores from different anatomical sections of the prostate. However, TRUS has low sensitivity and is limited by significant overlap in the appearances of benign changes and malignancy (1–3). Prostate cancer remains the only solid tumor where biopsy is not directed at visualized lesions. There is rapidly growing interest in imaging methods to guide biopsy, which creates opportunities for interventionalists to leverage their expertise in image-guided procedures to contribute to this field.

Until recently, PSA screening has been the primary determinant for prostate biopsies in the general population but has resulted in over-diagnosis and over-treatment, without a definite survival benefit (4–6). Recently, the role of PSA screening in prompting biopsies has been called into question by the United States Preventive Task Force (7). PSA screening is now performed on an individualized basis after discussion of the risks and benefits of screening.

Prior to imaging methods, the prostate biopsy was guided by direct palpation. The use of TRUS began in the early 1970s with advent of ultrasound, and the original sextant biopsy scheme (total of six cores from the base, middle, and apex bilaterally) improved detection over digital guidance (8). Meta-analysis of 87 studies showed that doubling the number of cores (to twelve, by obtaining medial and lateral cores in the traditional 6-sextant scheme) improved cancer detection by 31% (9). Thus, the 12–18 core systematic biopsy became the standard in the 2000s. The increase in biopsy cores from six to twelve is not associated with measurable increased post-biopsy morbidity (10). The logical extension of this was saturation biopsy, which involves sampling the entire gland but is reserved for patients with persistently rising PSA and a history of negative biopsies (11).

In an attempt to provide better image guidance of prostate biopsies, a number of ultrasound-based technologies were introduced. These included Doppler-targeted strategies, real-time elastography, and ultrasound contrast agents. Other ultrasound techniques include 3D ultrasound (TargetScan, Envisioneering Medical Technologies, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) and tissue characterization algorithms (HistoScanning, Advanced Medical Diagnostics SA/NV, Waterloo, Belgium).

MRI of the prostate appears to be the most sensitive method for detecting prostate cancer by imaging. Direct biopsies under MR guidance have been attempted but prove to be inefficient and uncomfortable for patients. Higher cancer detection rates were demonstrated when the pre-biopsy MRI was fused to a real-time TRUS to guide biopsy to lesions seen on MRI (12). Techniques for fusion guidance include electromagnetic tracking (UroNav, Invivo, Gainesville, Florida, USA) image processing (Medical Image Management System, Canada and Urostation, Koelis, La Tronche, France), optical tracking (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA), and encoded mechanical arm/passive robotic (Artemis, Eigen, Grass Valley, California, USA).

Prostate anatomy and zonal distribution

The prostate gland is comprised of peripheral, transitional, and central zones. The peripheral zone is disc-shaped and constitutes 70% of the prostate gland. Its ducts radiate laterally from the urethra lateral and distal to the verumontanum (13). The central zone constitutes 25% of the prostate gland, and surrounds the prostatic urethra. Its ducts arise close to the ejaculatory duct orifices at the verumontanum and branch laterally near the prostate base. The transitional zone, which is not separable from the central zone on MR imaging, is found anterior and lateral to the prostatic urethra and constitutes the remaining 5% of the glandular prostate. In benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), the central zones grow disproportionately and eventually surpass the volume of the peripheral zone (3).

Indications and contraindications for prostate biopsies

Indications for prostate biopsy include suspicion of prostate cancer, abnormal digital rectal exam, elevated serum PSA, or PSA velocity. Detailed screening guidelines are available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for early cancer diagnosis (14). The benefit of PSA screening is higher in African-Americans, patients with a positive family history, and patients taking 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (which increase the predictive capacity of PSA). PSA is non-specific; in addition to prostate cancer, prostatitis and BPH can cause the PSA level to rise (15). The American Cancer Society recommends that average risk men expected to live at least ten more years should discuss screening for prostate cancer at age 50 with their physician (16). Practically speaking, these recommendations may be difficult to interpret or to translate into reall-ife guidance. The benefits of PSA screening must be weighed against the risks of over-diagnosis.

The most commonly used threshold for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is 4.0ng/mL. Lowering the normal threshold for PSA to 2.5ng/mL has been suggested, but doubles the number of men defined as abnormal and does not clearly result in a benefit (17). Use of PSA velocity is also controversial. One study demonstrated an association between prostate cancer and PSA velocity >0.75ng/mL/year (18), however, the data from the European Randomized Study of Screening Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) in Rotterdam did not find that PSA velocity improved detection (19).

Relative contraindications to prostate biopsy include coagulopathy, painful anorectal conditions, significant immunosuppression, acute prostatitis, and an absent rectum.

Pre-procedural care and Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

The use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to transrectal prostate biopsies to reduce infection risk is recommended by the American Urological Association Best Practice Policy Statement on Urological Surgery Antimicrobial Prophylaxis guidelines (20). There is no single standard protocol, and practice patterns vary widely, often by geography and relative levels of bacterial antibiotic resistance in the community. However, fluoroquinolones are generally preferred due to their broad-spectrum coverage against Escherichia coli, the most likely infectious organism after biopsy. In addition, fluoroquinolones demonstrate excellent tissue penetration in the prostate. Alternatives to ciprofloxacin include aminoglycosides with metronidazole or clindamycin (20).

Quinolone resistance is responsible for the majority of infectious complications after prostate biopsy, with overall rates varying between <1% and 5% (21). If patients present with postprostate biopsy symptoms, empirical treatment with ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, or amikacin is indicated since ~50% of etiologic agents will be quinolone-resistant (22). There is currently no definite evidence for the superiority of a longer course of antibiotics (three days vs. one day) or multiple-dose treatment over single dosing (23). The prescription of a self-administered enema prior to biopsy is common, but the value of doing so is under debate (24).

Standard techniques

Nerve block

Bilateral nerve blockade facilitates the procedure immensely by helping to keep the patient immobile, and markedly improving patient comfort for an otherwise uncomfortable procedure. Blockade can be done quickly with ultrasound guidance targeting the lateral edge of the peri-prostatic tissues in several injections on each side, taking care to infiltrate the tissue planes surrounding the capsule, and adjusting the needle injections slightly to promote broad distribution to the nerve plexus. The needle should be advanced and retracted to make sure injections occur in multiple planes. Typical regimens include 10 ml of 1% lidocaine delivered bilaterally with a 22G 20cm needle via the ultrasound needle guide slowly injected in several different transrectal punctures. Aiming for the echogenic “fat triangle” between the posterior-lateral surface of the prostate, and the seminal vesicles is a common landmark. The anesthetic can also be administered adjacent to the apex, or into the Denonvilliers’ fascia (1).

Regardless of the site chosen, both sides of the periprostatic nerve plexus should be injected, and several minutes should be given to allow the lidocaine to distribute and take effect. It should be noted that injecting directly into the prostate gland is of no benefit (1). Care needs to be taken not to move the ultrasound transducer with the needle deployed, or rectal mucosa will be torn. Tracking the amount of the hub side of the needle outside the patient is the best way to guarantee that the needle is not inserted in the rectum and that it is safe to move the ultrasound probe. Topical lidocaine gel can also be used to reduce the discomfort of ultrasound probe insertion and needle puncture. Since the patient is awake, the nerve block can be repeated if inadequate.

Standard 12 core TRUS biopsy

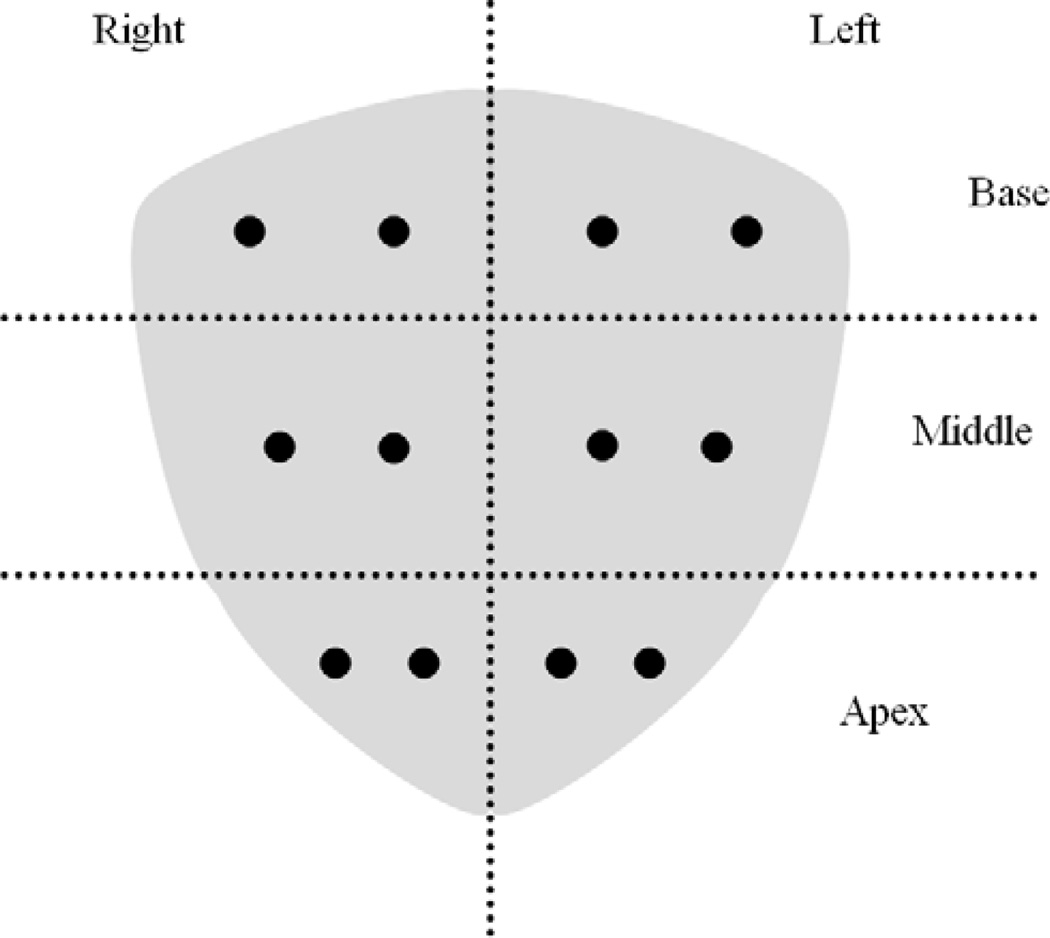

Patients are generally positioned in the left lateral decubitus position with knees to the chest and flexed hips on the table edge, allowing mobility of the ultrasound transducer. Core biopsies are obtained using a disposable spring-loaded biopsy needle (e.g. Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, Arizona, USA) inserted parallel to the end-fire ultrasound probe through an attached disposable transrectal needle guide (CIVCO, Kalona, Iowa, USA). The spring is much stronger than from standard percutaneous coaxial biopsy kits. Currently, the conventional biopsy consists of twelve cores: the base, middle, and apex sextant regions are sampled in both the lateral and medial aspects of each sextant region bilaterally (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Coronal view of standard extended 12-core prostate biopsy scheme, dots estimate planned biopsy sites.

Ultrasound guided biopsy

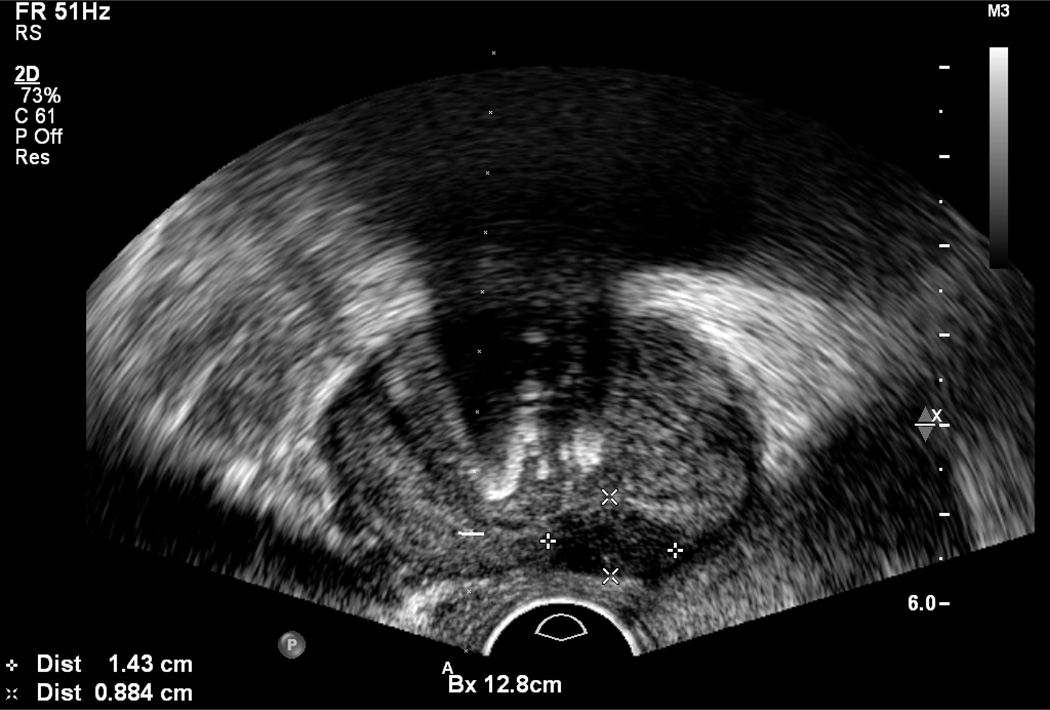

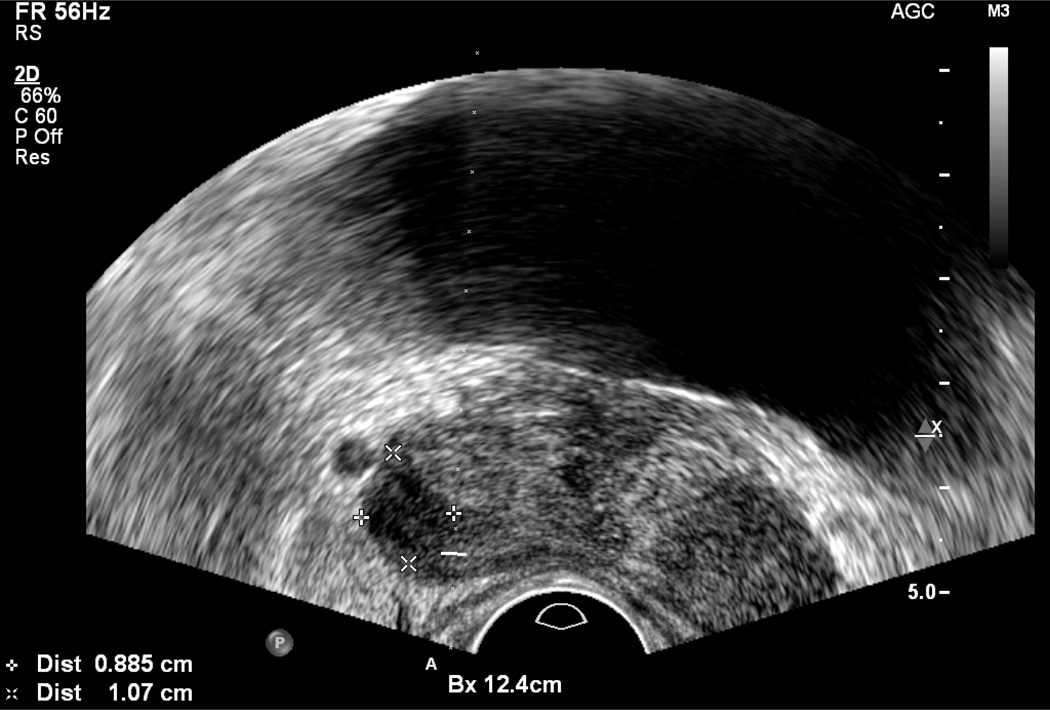

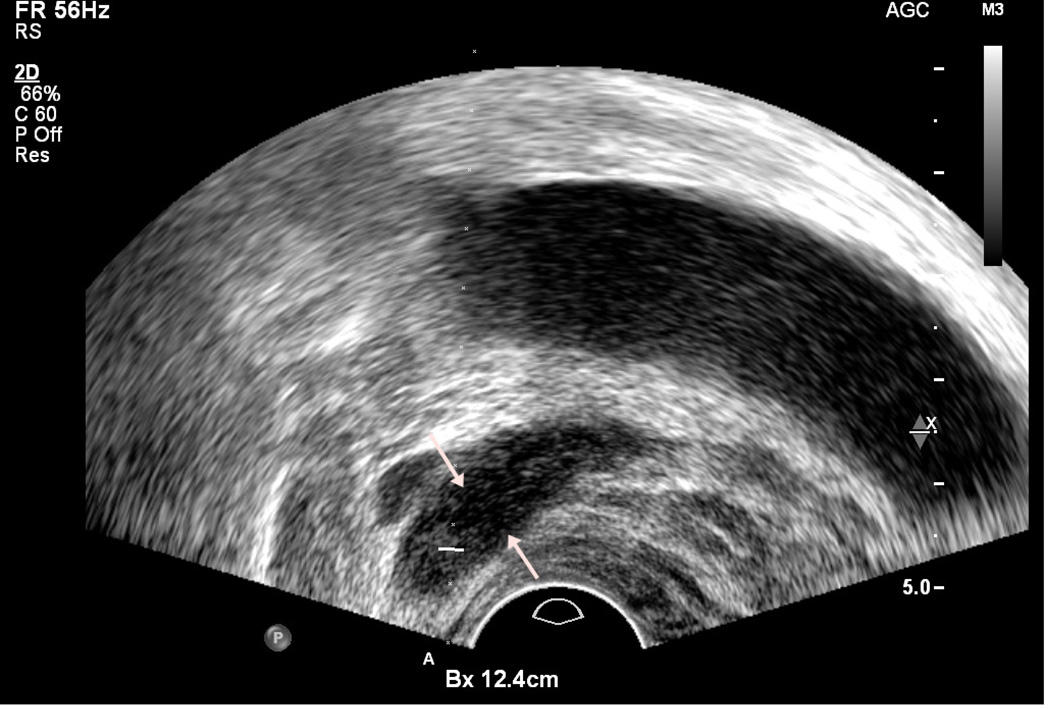

A standard TRUS guided biopsy begins with a brief survey of the prostate gland to identify nodules, which are most often in the peripheral zone and usually hypoechoic, but may be hyperechoic (Figure 3). Unfortunately, gray scale TRUS has low sensitivity and specificity for prostate cancer compared with MRI.

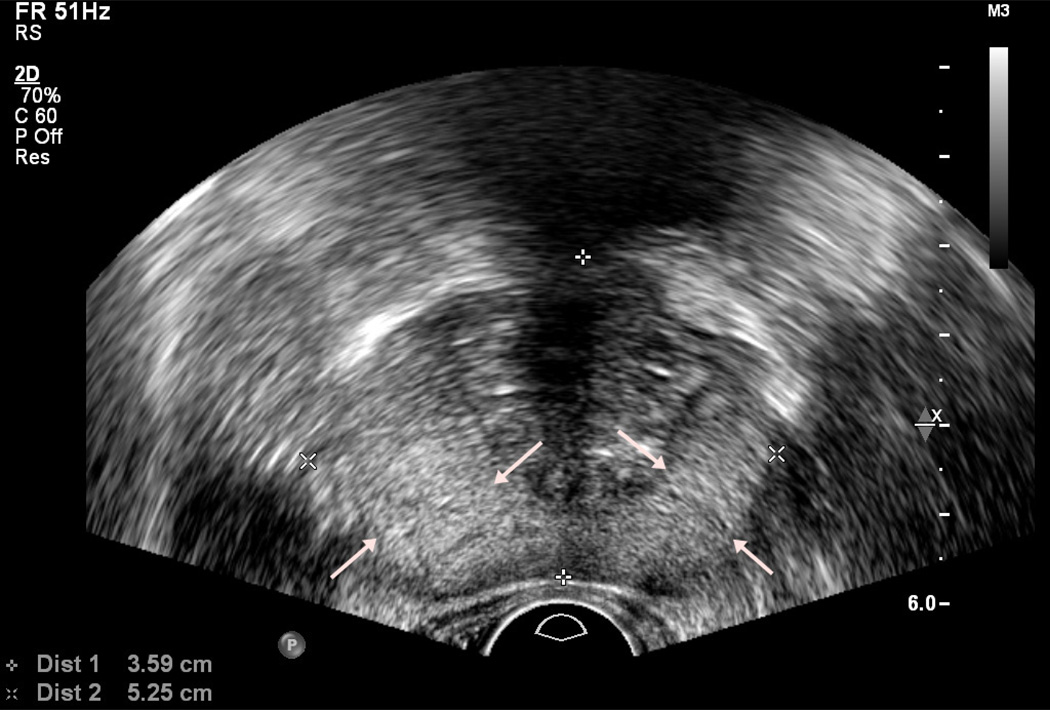

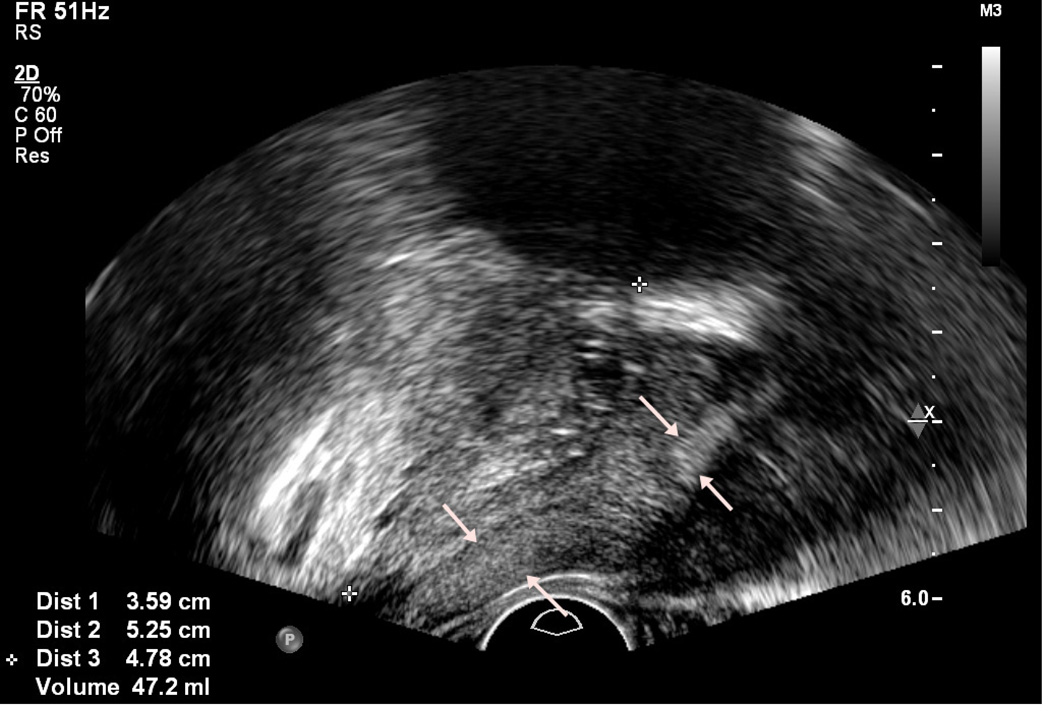

Figure 3.

Axial image demonstrating central calcifications and a hypoechoic lesion (cursors)

To confirm the presence of a nodule, scanning should be performed in two planes, typically the axial and sagittal planes. This can be accomplished by rotating the probe slowly while maintaining the nodule in view (Figure 4). On sagittal imaging, imaging is typically in an extreme lateral plane because the image at this plane is composed almost entirely of peripheral zone.

Figure 4.

Hypoechoic lesion (cursors) on axial view (a), and ultrasound probe was rotated to show lesion (arrows) on sagittal view (b)

End-fire probes have curved array detectors on the probe tip while side-fire ultrasound probes have longitudinal transducers. End-fire transrectal ultrasound probes are reported to have higher cancer detection rates compared to side-fire ultrasound probes (25,26) which are limited to a longitudinal biopsy trajectory. End-fire probes allow better sampling in lateral and anterior aspects of prostatic tissue which are typically undersampled (26). However, in one prospective study involving experienced urologists, ultrasound probe configurations did not differ in cancer detection rates (27).

Calcifications and linear hypoechoic “bands” in the peripheral zone with very straight edges (which are best visualized in only one plane) are common benign findings. Central region nodules can have a wide variety of appearances but commonly represent BPH. In general, TRUS is poor at determining the presence of extracapsular extension. Once the targets are identified, core biopsies can be obtained with the TRUS biopsy guide electronically superimposed over the ultrasound image. Movement of the TRUS probe should be carefully considered as it is easy to become anatomically disoriented. TRUS manipulations should be performed in one plane at a time. This allows for better control over the planning of the needle pathway with real time imaging feedback, and it is easier to retrace steps to re-target the biopsy if a systematic approach is used.

Saturation biopsy

Saturation biopsy refers to obtaining many cores (often 20+) throughout the prostate aiming to sample virtually all of the tissue at regular intervals. Saturation biopsy is not used as the initial form of prostate biopsy (11), and has been typically reserved for patients with previous negative biopsies that continue to have a high degree of clinical suspicion for prostate cancer. The risks of missing significant cancer should be balanced with the possibility of detecting a clinically unimportant cancer. Surprisingly, the increased number of cores does not appear to be associated with a detectable increased risk of complications (11). However, the high cost (each biopsy is often separately billed) and requirement for deeper levels of anesthesia in the hospital setting make it less attractive.

Fine needle aspiration

Most prostate biopsies are obtained as core samples. Although controversial, some studies have shown that fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of the prostate gland may be as effective as core biopsies in cancer detection, but not in characterization or scoring (28). However, since Gleason scoring is such an important part of prostate cancer management, it is unlikely that FNA will replace core biopsies.

Transperineal biopsy

Although the majority of prostate biopsies are obtained transrectally, there are reasons to consider the transperineal approach. Anatomically, the transperineal approach may identify proportionally more anterior tumors (29). Moreover, biopsy does not entail crossing the rectal mucosa with presumably lower rates of infections. Detection rates, cancer core rates, and complications are generally comparable between the transperineal and transrectal approach (30). Transperineal biopsy may be used for patients who do not have rectal access due to surgery.

One disadvantage is that transperineal biopsies may require spinal or general anesthesia, or deep sedation, limiting its usage in the office setting. However, the transperineal approach may be useful in guiding biopsies under MRI. A brachytherapy grid or stepper, which is a plastic block with pre-drilled holes is used to direct the needles to the proper location. Robotic or semiautomatic needle guide devices are also available for use with MRI guidance via the transperineal approach (Invivo, Gainesville, Florida, USA).

Such approaches may also prove useful for focal laser ablation or cryo-ablation. When thermal energy methods (e.g. laser ablation) are utilized, MR guidance can provide real time thermometry of the treatment to the operator of the ablation device.

Complications

Prostate biopsy is generally considered to be safe. On initial biopsy, the risk of sepsis is <0.1% and the risk of rectal bleeding is 2.1%. Mild hematuria and hematospermia are common, occurring in 62% and 9.8% of patients respectively. The morbidity of repeat biopsy does not differ significantly from the initial biopsy (31). Patients should be counseled to hydrate well after biopsy and to expect to see blood in their urine for several days. Since hematospermia is typically not clinically meaningful but may last many weeks, it should be discussed to avoid anxiety. Persistent blood, dizziness, or fever should be reported immediately. In a study of Medicare participants, the overall risk of hospitalization within 30 days of a prostate biopsy (6.9%) was significantly higher than randomly selected controls (2.7%) (32). When a transrectal prostate biopsy is obtained, fecal matter may be introduced into the prostate and presents an infection risk. While it is plausible that a self-administered enema may reduce the fecal matter present, it has not been shown to decrease complication rates and serious infections can occur not withstanding pre-procedure enemas (24).

Advanced biopsy guidance techniques

Doppler and Elastography

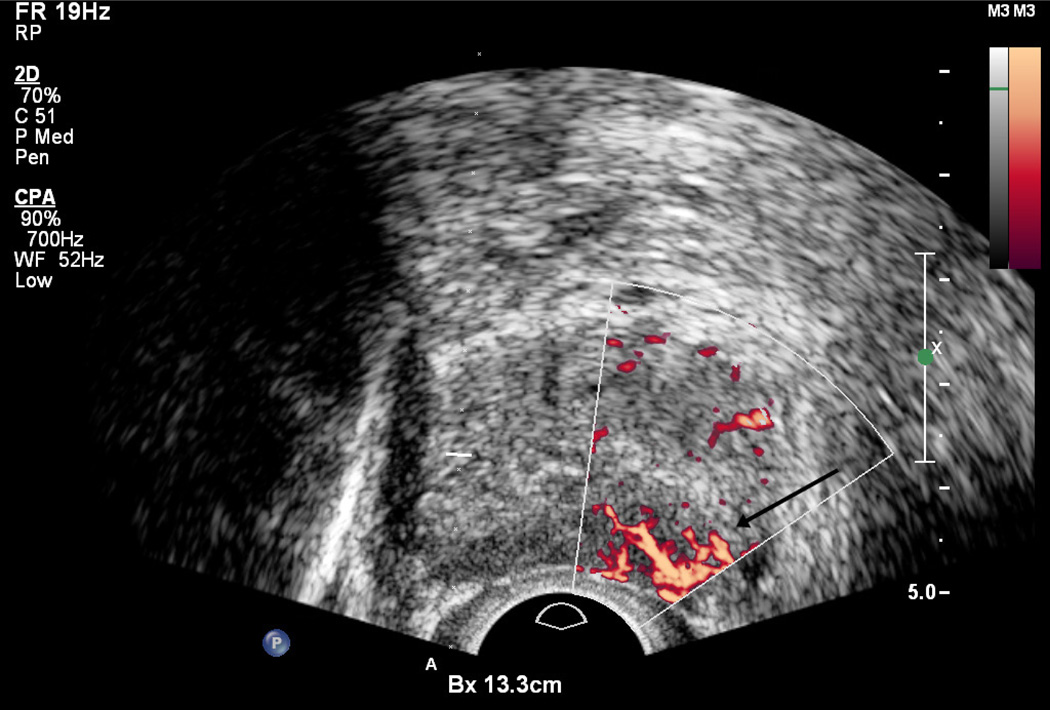

Color and Power Doppler are based on the frequency shift caused by the movement of specular reflectors (typically red blood cells) relative to the ultrasound probe. Thus, detection of the Doppler shift can show the direction and speed of blood flow. Flow is usually minimal and symmetric in the normal prostate gland, although Color Doppler signal may be seen in neurovascular bundles and pericapsular and periurethral arteries as well as a web of peri-prostatic veins (1). Areas of focal or asymmetric hypervascularity within the gland are more likely to demonstrate malignancy (Figure 5). However, the finding is non-specific, as some tumors are hypovascular whereas some benign lesions, particularly prostatitis, are hypervascular (33). Color Doppler can improve sensitivity, but the effect on specificity is not as pronounced (34). The term “Color Doppler” refers to the peak Doppler shift measured by the probe. The term “Power Doppler”, which is also displayed in color, refers to the area under the Doppler curve and tends to have better signal-to-noise ratios. However, Power Doppler is not markedly more accurate than that of Color Doppler (35).

Figure 5.

Region of the left base peripheral zone demonstrates hypervascularity (arrow).

Cancerous tissue often has increased blood flow which can be seen with ultrasound contrast agents. Ultrasound contrast agents are microbubbles with a thin membrane containing gas.. In one large retrospective study, the per-patient detection rate of contrast-enhanced Doppler ultrasound targeted biopsy was 27%, compared to 23% with systematic biopsy, with a detection rate of 31% when both modalities were combined (36). When contrast enhanced Doppler targeted biopsy was positive, significantly higher Gleason scores were found (37).

Ultrasound elastography quantifies the stiffness of tissue during the manual compression of the gland by the transducer (1). Tumors typically have increased stiffness compared to the surrounding tissue. This can also be detected with shear-wave elastography, which analyzes the ultrasound signal from a propagating a shear wave through tissue to measure the elastic modulus in a quantitative and operator-independent way. Targeted sonoelastography may improve cancer detection versus systematic biopsy, even with fewer cores obtained, by having a significantly higher cancer detection rate per core (38).

Although the use of these techniques for targeted biopsy can potentially improve prostate cancer detection rates, limitations include the requirement for technical expertise, lack of updated equipment, subjective interpretive criteria, and inter-user variability.

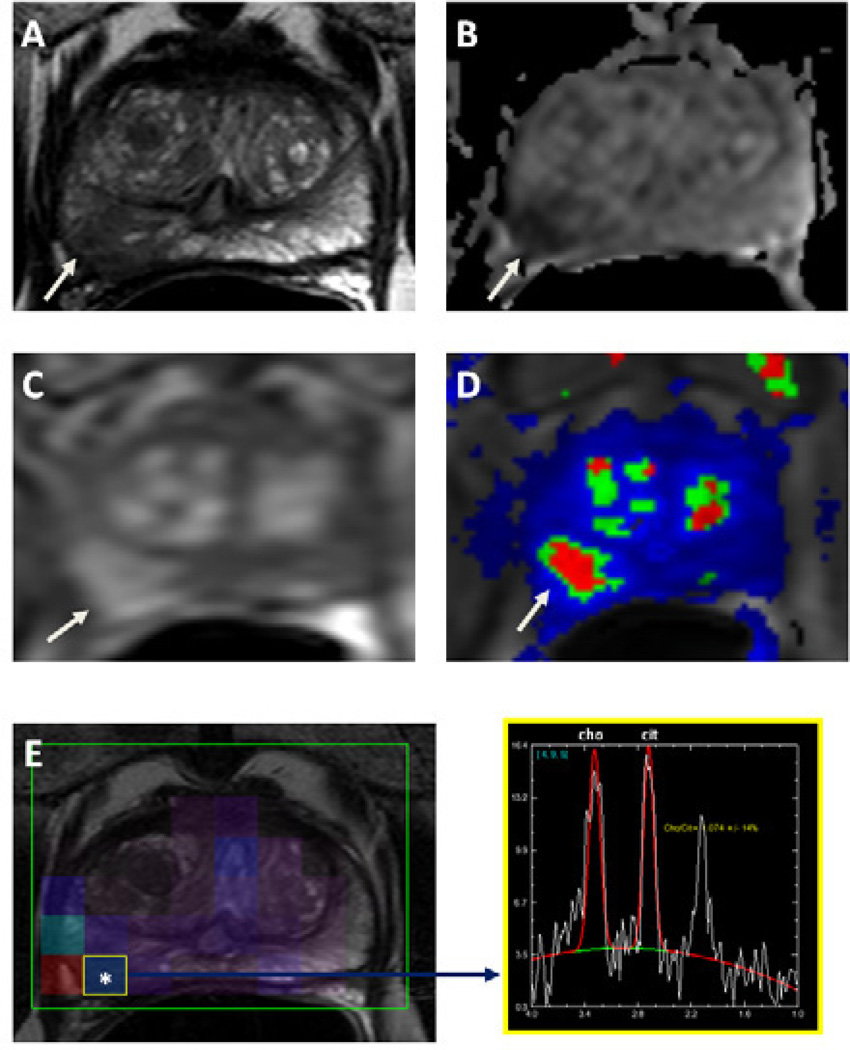

MRI as diagnostic tool

For non-invasive detection of prostate cancer, MRI has superior soft tissue resolution and better visualization of surrounding anatomy compared to conventional ultrasound. Classical prostate MRI involves placement of an endo-rectal coil in the patient’s rectum to obtain higher signal. Although a body or surface coil can be used instead, it reduces sensitivity and specificity of MRI. Nonetheless, modern 3T MRI scanners can obtain excellent quality imaging of the prostate with only multi-channel phased array surface coils. MRI relies on multiple parameters to achieve its accuracy. Multi-parametric imaging (mpMRI) consists of a combination of T2-weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging (which generate apparent diffusion coefficients maps), MR spectroscopy, and dynamic-contrast enhanced MRI (Figure 6). As more of these parameters turn positive, a lesion can be assigned a higher suspicion level (39,40) (Table 1).

Figure 6.

MRI of the prostate in a 63-year-old male with prostate cancer. Axial T2W image demonstrates a right sided low signal intensity lesion at the peripheral zone (arrow) (a), the lesion demonstrates diffusion restriction on corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient map of DWI MRI (b) (arrow); lesion shows increased enhancement on axial T1W DCE-MR image, whereas color coded kep map delineates the lesion (arrow) (d). MR spectroscopy demonstrates increased choline to citrate ratio within the right peripheral zone lesion (e). This lesion was biopsied under TRUS/MRI fusion system guidance and was found to include Gleason 8 (4+4) tumor.

Table 1.

Table showing a validated method of assigning suspicion levels for lesions based on positive sequences on mp-MRI

| T2-weighted | ADC maps from DWI |

MR Spectroscopy |

DCE | Suspicion Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Low |

| Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | Low |

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Low |

| Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Low |

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Low |

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Moderate |

| Positive | Negative | Negative | Positive | Moderate |

| Negative | Positive | Positive | Negative | Moderate |

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Moderate |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | Moderate |

| Positive | Positive | Negative | Positive | Moderate |

| Negative | Negative | Positive | Positive | Moderate |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | High |

To some extent, multiparametric MRI is predictive of tumor aggressiveness or grade. On T2-weighted (T2W) imaging, prostate cancers typically demonstrate lower signal intensity in comparison to the high signal intensity of normal prostate tissue, especially in the peripheral zone where most cancers reside (41). Gleason and D’Amico clinical risk scores are also negatively correlated with the apparent diffusion coefficients derived from diffusion-weighted MRI (39). On MR spectroscopy, prostate cancer foci are associated with decreases in citrate and an elevation of the choline peak, although this is the least commonly used of the four MR sequences, and requires considerable off-line data processing (42).

The assignment of suspicion level on mpMRI correlates with both the D’Amico risk stratification in visible lesions in the prostate and the cancer detection rate (39,43,40) (Table 1). In addition, mpMRI can be used to detect clinically significant anterior tumors, which may be missed on TRUS biopsy (44). mpMRI has been shown to improve the classification accuracy when used with standard clinical criteria for patient selection for active surveillance when compared to radical prostatectomy pathology (45). MRI can be used to accurately estimate tumor volumes (46), and in one study lesions localized on imaging had a 98% positive predictive value for prostate cancer as compared to whole gland histology, with greater sensitivity for higher grade tumors (47). Scores for tumor visibility on T2W MRI were also predictive of upgrading of Gleason scores on confirmatory biopsy when compared to initial staging (48).

MRI-guided biopsies

Since regions suspicious for tumor may be visualized on MRI, it can also be used to guide prostate biopsy (49). This may be particularly important in the setting of anterior or central lesions as systematic biopsy only targets the lateral peripheral zone. MRI guidance has been performed in both open and closed-bore MR systems. While open systems allow easy access to the patient, closed-bore systems offer much higher signal-to-noise ratios and thus, clearer prostate cancer visualization (3). Most in-gantry MRI guided biopsy studies have used a transrectal approach with a closed-bore 3T MR imaging system and an endorectal applicator (3). Diagnostic multiparametric MR imaging is performed prior to the biopsy for planning purposes (50). The needle guide may be filled with gadolinium-based contrast material for visualization on MR imaging, and there are commercial automated or robotic systems for transrectal and transperineal access. However, all devices must be MR-compatible, and the patient must be in the MRI gantry throughout the procedure, often in the uncomfortable prone position. Since they may occupy up to four slots on an MRI schedule, they are costly and burdensome on the limited resource of MRI. Urologists may also have limited access to an MRI suite reducing their willingness to refer patients for guided biopsy. MRI/US fusion has thus been developed to address these issues (51).

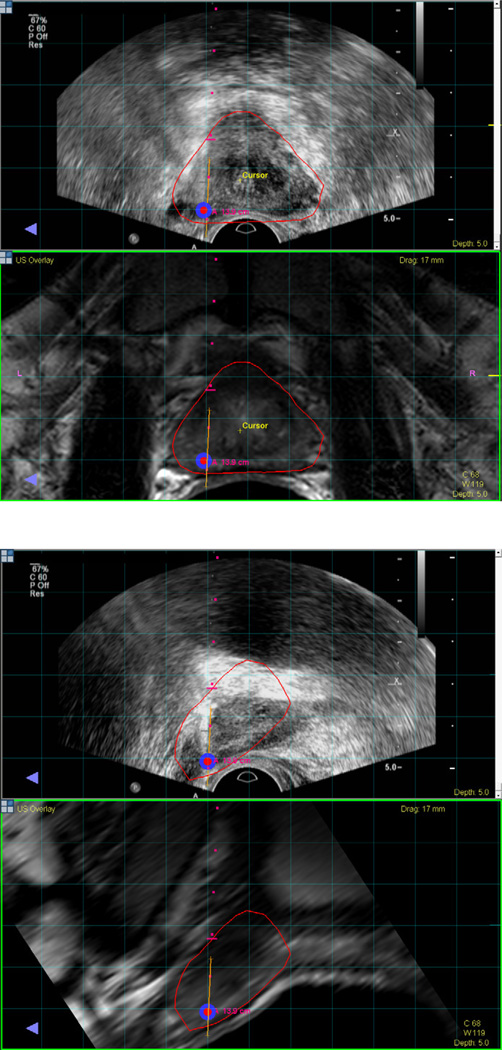

MRI/US fusion biopsies

MRI/US fusion superimposes pre-procedural diagnostic MRI images over a real-time ultrasound obtained at a different time and place. This allows targeting of suspicious lesions seen on MRI to be biopsied under real time ultrasound (Figure 7). The goal is to combine the high soft tissue resolution of the MR image with the real-time visualization of TRUS, in a more comfortable office setting without requiring the physical presence of the MRI gantry. The operator can guide the biopsy needle to specific locations after co-registering the imaging using electromagnetic sensors, which allow the system to determine the spatial position of the ultrasound probe. The registration process requires that a volumetric ultrasound image. Volumetric data can be obtained using by performing a fan-shaped sweep (UroNav, Invivo, Gainesville, Florida, USA), by spinning an end-fire ultrasound probe attached to a mechanical arm (Artemis, Eigen, Grass Valley, California, USA), or by using a 3D ultrasound probe (Urostation, Koelis, La Tronche, France). Co-registration with automatic motion compensation can re-register ultrasound and MRI if the patient moves or the prostate deforms.

Figure 7.

MRI registered with ultrasound visualized in the axial plane (a) and sagittal plane (b). A biopsy target is located in the left apical mid area of the prostate and visualized in red. Needle trajectory is shown by the red dots, and the orange line maps the biopsy location for archiving and later use.

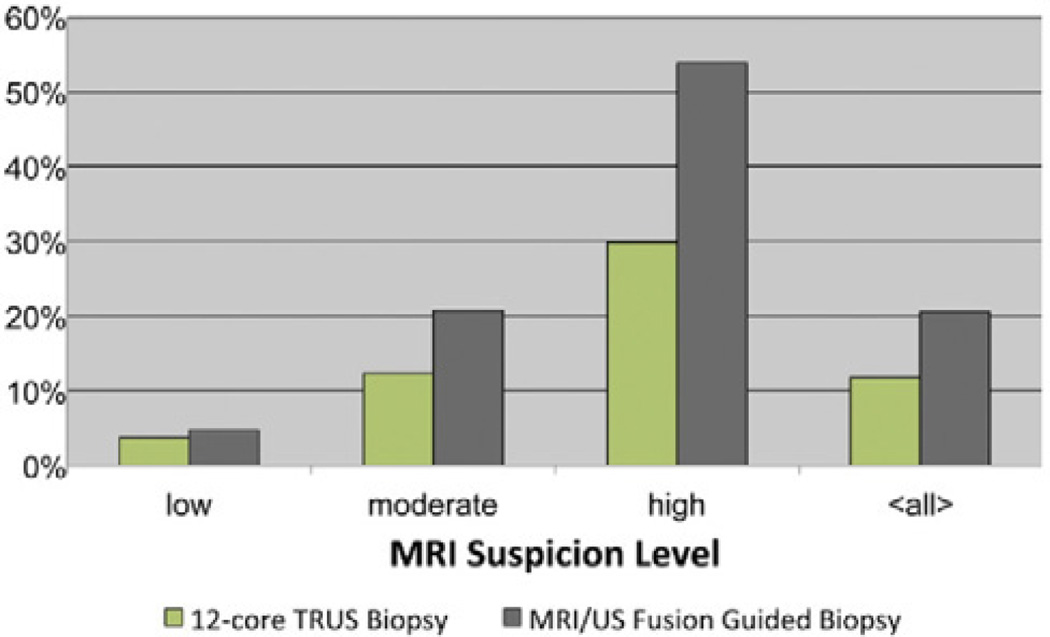

While some have attempted to perform “cognitive fusion”, i.e. use the human brain to estimate the location of a lesion on TRUS, results are better with a standardized fusion approach. Recent studies have shown that MRI/US fusion significantly increases the per-core and per-patient cancer detection rates (12). In one cohort, the per-core detection rate was 20.6% for MRI/US fusion in comparison with 11.7% for TRUS biopsy, and MRI/US fusion biopsy in conjunction with TRUS biopsy achieved an overall per-patient detection rate of 54.4% (12). The fusion between the two modalities is not exact and the error in one fusion system was 2.4 ± 1.2 mm in phantoms and patients, implying that small lesions may still be missed (51). In a prospective study, cores obtained from MRI/US fusion had approximately twice the detection rate of systematic TRUS biopsy overall, and were higher risk cancers (12) (Figure 8). In addition, MRI/US fusion prostate biopsy is capable of increasing detection rates in patients with enlarged prostates (52) and patients with a history of negative standard biopsies (53), where detection rates are lower. The addition of targeted cores upgrades the Gleason score over standard biopsy in 32% of cases (54). The targeted biopsies detected 67% more Gleason ≥4+3 tumors, but missed 36% of the Gleason ≤3+4 tumors. By targeting the suspicious lesions with this platform, it is possible to selectively sample areas more likely to contain malignancy and preferentially detect higher grade tumors more likely to warrant intervention. However, as a relatively new technique, long term outcomes of MRI/US fusion biopsy are not well studied.

Figure 8.

Cancer detection rates for biopsy cores were compared between standard 12-core TRUS biopsy alone and MRI/US fusion guided biopsy alone (Reproduced with permission from Pinto et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol 2011; 186:1281–5)

Repeat biopsy after initial negative biopsy

The decision whether to accept a negative biopsy result is dependent on the pre-test probability of a positive result, as well as the effect of a positive biopsy result on clinical management. The presence of clinical symptoms, palpable lesions, rising PSA levels, MR-visible lesions, or a strong family history of prostate cancer should prompt further exploration of an initial negative TRUS biopsy. In addition, there is a greater chance of achieving a survival benefit by pursuing cancer detection and treatment in younger and healthier patients.

In a study of sequential systematic biopsies, the detection rates of the first, second, third, and fourth biopsy were 22%, 10%, 5%, and 4% respectively, and the third and fourth biopsy attempts had slightly higher complication rates and detected lower grade tumors (55). Saturation biopsy may be able to increase detection rates in patients with prior negative biopsies (11). Most studies of MRI-guided fusion biopsy involve patients who have undergone at least one negative conventional TRUS biopsy. In this population, detection rates range from 38 – 59% (3). In a cohort of 195 men with prior negative biopsies, 37% of subjects were found to have cancer using a combination of TRUS-guided and MR/US fusion biopsy (53). High grade (Gleason 8+) cancer was found in 11% of subjects, and 55% of these high grade cancers were missed on standard biopsy. Pathological upgrading occurred in 39% as a result of fusion biopsy.

Discussion

Multimodality MRI, ultrasound, and image guided procedures such as fusion biopsy are altering the standard of care for prostate cancer. This review highlights the importance of imaging and fusion approaches for accurate diagnosis and characterization. Advanced imaging like MRI has not yet been broadly applied to screen, diagnose, or target biopsy for prostate cancer. However, there is great interest in these methods as it is recognized that standard biopsies may create more problems than they solve. Specific indications and patient selection have not yet been well defined for when to use MRI or fusion technology. Consensus on the ideal techniques should become clearer as data emerges on when to use which approach. Possible clinical indications include T1c lesions, prior negative TRUS biopsy with high clinical suspicion, or MRI-identified lesions.

The standard method for “blind” TRUS biopsy has a low sensitivity and specificity for prostate cancer. This “blind” systematic TRUS supposedly distributes the biopsies evenly, but the distribution of these needles is highly variable and operator-dependent In one autopsy study, the sensitivity of detecting cancer by obtaining six cores from each of the medial and lateral peripheral zones was estimated at 53% (56). Beyond 12 cores, the diagnostic yield seems to depend more on the biopsy site than the number of cores obtained (56). This is concordant with the observation that saturation biopsy does not improve detection rates when used as an initial technique (11). This imposes a fundamental limitation to the sensitivity of “blind” techniques, since the amount of un-sampled tissue dwarfs the amount that is obtained.

The fusion approach has not yet been widely adopted, but has become widely available commercially, with at least three companies offering competing products. Cancer detection thus depends on malignancy being present in anatomical regions that were selected a priori, which may explain why some patients with high suspicion for prostate cancer can have repeatedly negative biopsies. The role of imaging guidance with MRI, MRI/TRUS fusion, and advanced ultrasound tools offers interventional and diagnostic radiologists new opportunities to contribute to the field of prostate biopsy. In all likelihood, the impact of MRI/TRUS fusion technology will rely upon multi-disciplinary teamwork, where radiologists interpret the MRI images, which are then used by urologists or interventional radiologists to perform office-based fusion biopsy. The best procedures will leverage the skill sets of both urologists and radiologists in a collaborative team approach. The use of real-time navigation systems for spatial cancer mapping could improve the diagnostic yield of biopsy and could play a major role in the screening, evaluation, diagnosis, surveillance and management of the prostate cancer patient.

Figure 1.

Normal anatomy of prostate on axial (a) and sagittal (b) view. Peripheral zone is indicated by arrows.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information: Supported by the Center for Interventional Oncology, the National Cancer Institute and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. NIH and Philips have a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. This research was made possible through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from Pfizer Inc, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, as well as other private donors. For a complete list, please visit the Foundation website at http://www.fnih.org/work/programs-development/medicalresearch-scholars-program). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SIR clause: This material has not been previously presented at an SIR Annual Scientific Meeting.

References

- 1.Harvey CJ, Pilcher J, Richenberg J, Patel U, Frauscher F. Applications of transrectal ultrasound in prostate cancer. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(Spec No 1):S3–S17. doi: 10.1259/bjr/56357549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raja J, Ramachandran N, Munneke G, Patel U. Current status of transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yacoub JH, Verma S, Moulton JS, Eggener S, Aytekin O. Imaging-guided prostate biopsy: conventional and emerging techniques. Radiographics. 2012;32:819–837. doi: 10.1148/rg.323115053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–1328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1310–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilic D, Neuberger MM, Djulbegovic M, Dahm P. Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD004720. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004720.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin K, Lipsitz R, Janakiraman S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet] Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [cited 2013 Sep 1]. Benefits and Harms of Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening for Prostate Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43401/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodge KK, McNeal JE, Terris MK, Stamey TA. Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate. J Urol. 1989;142:71–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38664-0. discussion 74–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichler K, Hempel S, Wilby J, Myers L, Bachmann LM, Kleijnen J. Diagnostic value of systematic biopsy methods in the investigation of prostate cancer: a systematic review. J Urol. 2006;175:1605–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger AP, Gozzi C, Steiner H, et al. Complication rate of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: a comparison among 3 protocols with, 6, 10 and 15 cores. J Urol. 2004;171:1478–1480. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000116449.01186.f7. discussion 1480–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones JS, Patel A, Schoenfield L, Rabets JC, Zippe CD, Magi-Galluzzi C. Saturation technique does not improve cancer detection as an initial prostate biopsy strategy. J Urol. 2006;175:485–488. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto PA, Chung PH, Rastinehad AR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;186:1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeal JE. The zonal anatomy of the prostate. The Prostate. 1981;2:35–49. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990020105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection v2.2012 [Internet] doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0016. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadler RB, Humphrey PA, Smith DS, Catalona WJ, Ratliff TL. Effect of inflammation and benign prostatic hyperplasia on elevated serum prostate specific antigen levels. J Urol. 1995;154:407–413. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf AMD, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:70–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels in the United States: Implications of Various Definitions for Abnormal. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1132–1137. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter HB, Pearson JD, Metter EJ, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA. 1992;267:2215–2220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schröder FH, Roobol MJ, van der Kwast TH, Kranse R, Bangma CH. Does PSA velocity predict prostate cancer in pre-screened populations? Eur Urol. 2006;49:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.026. discussion 465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf JS, Jr, Bennett CJ, Dmochowski RR, Hollenbeck BK, Pearle MS, Schaeffer AJ. Best practice policy statement on urologic surgery antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol. 2008;179:1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagenlehner FME, van Oostrum E, Tenke P, et al. Infective complications after prostate biopsy: outcome of the Global Prevalence Study of Infections in Urology (GPIU) 2010 and 2011, a prospective multinational multicentre prostate biopsy study. Eur Urol. 2013;63:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feliciano J, Teper E, Ferrandino M, et al. The incidence of fluoroquinolone resistant infections after prostate biopsy--are fluoroquinolones still effective prophylaxis? J Urol. 2008;179:952–955. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.071. discussion 955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zani EL, Clark OAC, Rodrigues Netto N., Jr Antibiotic prophylaxis for transrectal prostate biopsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD006576. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006576.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaytoun OM, Anil T, Moussa AS, Jianbo L, Fareed K, Jones JS. Morbidity of prostate biopsy after simplified versus complex preparation protocols: assessment of risk factors. Urology. 2011;77:910–914. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul R, Korzinek C, Necknig U, et al. Influence of transrectal ultrasound probe on prostate cancer detection in transrectal ultrasound-guided sextant biopsy of prostate. Urology. 2004;64:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ching CB, Moussa AS, Li J, Lane BR, Zippe C, Jones JS. Does transrectal ultrasound probe configuration really matter? End fire versus side fire probe prostate cancer detection rates. J Urol. 2009;181:2077–2082. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.035. discussion 2082–2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rom M, Pycha A, Wiunig C, et al. Prospective randomized multicenter study comparing prostate cancer detection rates of end-fire and side-fire transrectal ultrasound probe configuration. Urology. 2012;80:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maksem JA, Berner A, Bedrossian C. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the prostate gland. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:778–785. doi: 10.1002/dc.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hossack T, Patel MI, Huo A, et al. Location and pathological characteristics of cancers in radical prostatectomy specimens identified by transperineal biopsy compared to transrectal biopsy. J Urol. 2012;188:781–785. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hara R, Jo Y, Fujii T, et al. Optimal approach for prostate cancer detection as initial biopsy: prospective randomized study comparing transperineal versus transrectal systematic 12-core biopsy. Urology. 2008;71:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Djavan B, Waldert M, Zlotta A, et al. Safety and morbidity of first and repeat transrectal ultrasound guided prostate needle biopsies: results of a prospective European prostate cancer detection study. J Urol. 2001;166:856–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, Ricker W, Schaeffer EM. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011;186:1830–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson ED, Slotoroff CB, Gomella LG, Halpern EJ. Targeted biopsy of the prostate: the impact of color Doppler imaging and elastography on prostate cancer detection and Gleason score. Urology. 2007;70:1136–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy C, Buy X, Lang H, Saussine C, Jacqmin D. Contrast enhanced color Doppler endorectal sonography of prostate: efficiency for detecting peripheral zone tumors and role for biopsy procedure. J Urol. 2003;170:69–72. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000072342.01573.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halpern EJ, Strup SE. Using gray-scale and color and power Doppler sonography to detect prostatic cancer. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:623–627. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitterberger MJ, Aigner F, Horninger W, et al. Comparative efficiency of contrastenhanced colour Doppler ultrasound targeted versus systematic biopsy for prostate cancer detection. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2791–2796. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitterberger M, Pinggera GM, Horninger W, et al. Comparison of contrast enhanced color Doppler targeted biopsy to conventional systematic biopsy: impact on Gleason score. J Urol. 2007;178:464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.107. discussion 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pallwein L, Mitterberger M, Struve P, et al. Comparison of sonoelastography guided biopsy with systematic biopsy: impact on prostate cancer detection. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:2278–2285. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0606-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turkbey B, Shah VP, Pang Y, et al. Is apparent diffusion coefficient associated with clinical risk scores for prostate cancers that are visible on 3-T MR images? Radiology. 2011;258:488–495. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rais-Bahrami S, Siddiqui MM, Turkbey B, et al. Utility of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging suspicion levels for detecting prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1721–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hricak H, Choyke PL, Eberhardt SC, Leibel SA, Scardino PT. Imaging prostate cancer: a multidisciplinary perspective. Radiology. 2007;243:28–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431030580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurhanewicz J, Swanson MG, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB. Combined Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopic Imaging Approach to Molecular Imaging of Prostate Cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:451–463. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rastinehad AR, Baccala AA, Jr, Chung PH, et al. D’Amico risk stratification correlates with degree of suspicion of prostate cancer on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;185:815–820. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrentschuk N, Haider MA, Daljeet N, et al. “Prostatic evasive anterior tumours”: the role of magnetic resonance imaging. BJU Int. 2010;105:1231–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turkbey B, Pinto PA, Mani H, et al. Prostate cancer: value of multiparametric MR imaging at 3 T for detection--histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2010;255:89–99. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O, et al. Correlation of magnetic resonance imaging tumor volume with histopathology. J Urol. 2012;188:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turkbey B, Mani H, Shah V, et al. Multiparametric 3T prostate magnetic resonance imaging to detect cancer: histopathological correlation using prostatectomy specimens processed in customized magnetic resonance imaging based molds. J Urol. 2011;186:1818–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vargas HA, Akin O, Afaq A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for predicting prostate biopsy findings in patients considered for active surveillance of clinically low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:1732–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beyersdorff D, Winkel A, Hamm B, Lenk S, Loening SA, Taupitz M. MR Imaging– guided Prostate Biopsy with a Closed MR Unit at 1.5 T: Initial Results. Radiology. 2005;234:576–581. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342031887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pondman KM, Fütterer JJ, ten Haken B, et al. MR-guided biopsy of the prostate: an overview of techniques and a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2008;54:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu S, Kruecker J, Turkbey B, et al. Real-time MRI-TRUS fusion for guidance of targeted prostate biopsies. Comput Aided Surg. 2008;13:255–264. doi: 10.1080/10929080802364645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walton Diaz A, Hoang AN, Turkbey B, et al. Can magnetic resonance-ultrasound fusion biopsy improve cancer detection in enlarged prostates? J Urol. 2013;190:2020–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vourganti S, Rastinehad A, Yerram NK, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound fusion biopsy detect prostate cancer in patients with prior negative transrectal ultrasound biopsies. J Urol. 2012;188:2152–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Truong H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound-fusion biopsy significantly upgrades prostate cancer versus systematic 12-core transrectal ultrasound biopsy. Eur Urol. 2013;64:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Djavan B, Ravery V, Zlotta A, et al. Prospective evaluation of prostate cancer detected on biopsies 1, 2, 3 and 4: when should we stop? J Urol. 2001;166:1679–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haas GP, Delongchamps NB, Jones RF, et al. Needle Biopsies on Autopsy Prostates: Sensitivity of Cancer Detection Based on True Prevalence. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1484–1489. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]