Abstract

Background and Purpose

We examined blood pressure 1 year after stroke discharge and its association with treatment intensification.

Methods

We examined the systolic blood pressure (SBP) stratified by discharge SBP (<140; 141 to 160; or >160 mmHg) among a national cohort of Veterans discharged after acute ischemic stroke. Hypertension treatment opportunities were defined as outpatient SBP >160 mm Hg or repeated SBPs >140 mm Hg. Treatment intensification was defined as the proportion of treatment opportunities with antihypertensive changes (range 0 to 100%, where 100% indicates that each elevated SBP always resulted in medication change).

Results

Among 3153 ischemic stroke patients, 38% had at least one elevated outpatient SBP eligible for treatment intensification in the 1 year post stroke. Thirty percent of patients had a discharge SBP <140mmHg; and an average 1.93 treatment opportunities and treatment intensification occurred in 58% of eligible visits. Forty seven percent of patients discharged with SBP 141 to160 mmHg had an average of 2.1 opportunities for intensification and treatment intensification occurred in 60% of visits. Sixty three percent of the patients discharged with an SBP >160mmHg had an average of 2.4 intensification opportunities, and treatment intensification occurred in 65% of visits.

Conclusion

Patients with discharge SBP >160mmHg had numerous opportunities to improve hypertension control. Secondary stroke prevention efforts should focus on: initiation and review of antihypertensives prior to acute stroke discharge; management of antihypertensives and titration; and patient medication adherence counseling.

INTRODUCTION

Having a stroke increases risk for recurrent stroke.1, 2 Systolic blood pressure (SBP) remains the most modifiable risk factor for stroke and antihypertensive medications are efficacious in reducing SBP.3 Patients who experience a recent stroke may be more motivated to adhere to their medications and attain better risk factor control. Conversely, a recent study of patients with a stroke demonstrated that 25% had discontinued at least one secondary prevention medication within 3 months of hospital discharge.4

Given that hypertension is the risk factor with the greatest population attributable risk for stroke and is present in the majority of patients5, we were interested in examining the patterns of hypertension management in the one-year post-stroke period. Uncontrolled SBP after a stroke may be related to a variety of factors including non-adherence, inappropriate medication selection, clinical inertia, or resistant hypertension refractory to treatment. The aim of this study was to determine whether some of these factors are associated with uncontrolled SBP. We determined the quality of hypertension care after a stroke by describing: (1) the patient's SBP trajectory after stroke; (2) antihypertensive treatment intensification (proportion of treatment intensification opportunities [denominator] associated with medication intensifications [numerator]); and (3) the association between patient adherence and treatment intensification. This first step was important to understanding factors that impact uncontrolled hypertension in the post stroke period and in designing interventions to improve risk factors among ischemic stroke patients.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

The Office of Performance Measurement Stroke Special Study was a retrospective cohort of Veterans admitted during Fiscal Year 2007 with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke, identified using a modified high specificity algorithm of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes (N=5721 possible stroke events).6-8 A systematic sample of 5000 records that included all ischemic stroke patients at hospitals with less than 55 stroke hospitalizations and an 80% random sample of patients at hospitals with more than 55 stroke hospitalizations were selected for abstraction. Because of this sampling, the number of patients per hospital ranged from 1 to 198 (mean=38 and standard deviation [SD] =28). Among the 307 data elements abstracted, 90% demonstrated good or very good interrater reliability [Kappa statistic ≥0.70].9

Abstracted data was linked to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) outpatient treatment and pharmacy files. Data on antihypertensive prescriptions dispensed included medication name, date filled, days supplied, quantity and dosage. Vital signs data included all outpatient SBP measurements. Dates of death were obtained from VHA vital status files. For Medicare eligible Veterans, we obtained supplemental race data from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. The study received institutional review board approval.

Study Population

Veterans were excluded if the hospitalization was for: rehabilitation, elective carotid endarterectomy, or another condition in which they experienced an in-hospital ischemic stroke. We excluded patients who died during their index hospitalization, had hospice or long-term care or did not have post-discharge SBP values. We included SBP from the following clinics: internal medicine; primary care/medicine; women's health; mental health primary care; geriatrics; hypertension; cardiology; anticoagulation; diabetes/ endocrine; infectious disease; renal/nephrology; pulmonary/chest; or neurology. These clinics were chosen because these clinicians often manage BP by prescribing antihypertensive medications.

Outcome: Clinically appropriate treatment intensification

Clinically appropriate treatment intensification was defined as the proportion of medication intensifications (numerator) to medication intensification opportunities (denominator) of elevated SBP in the year post stroke. This proportion could range from 0 to 100% where 100% represented a patient wherein every elevated SBP opportunity resulted in medication intensification.

Antihypertensive Medication Intensification (Numerator)

Medication intensification occurred if a new antihypertensive was added, a dose was increased, or a medication switch occurred within 30 days of an opportunity. The date of the new prescription or dose change was the intensification date. For validation, we randomly reviewed 38 charts and correctly identified 12/12 patients who intensified therapy (positive predictive value 100%, 95% confidence intervals [CI] 75.8, 100). We also predicted 21 out of 26 patients as not having intensified therapy (negative predictive value =80.8, 95% CI 62.1, 91.5). We missed 5/26 patients (20%) in which the provider told the patient to change the dose and did not alter the prescription.

Opportunities of Elevated BP (Denominator)

A visit was a potential intensification opportunity if it satisfied one of three criteria: (1) SBP >160 mm Hg, (2) the second of two consecutive visits where the SBP was >140 mmHg or (3) the SBP in which more than 50% of the preceding visits were >140 mm Hg. If multiple BP measures were recorded on the same day, then the lowest BP was utilized. We excluded SBPs considered data entry errors or improbable outpatient values; including, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >SBP, SBP < 60 mmHg, DBP < 30mmHg, or SBP minus DBP <10mmHg.

To allow medication changes to take effect and assure that the SBP was not falsely elevated; we excluded opportunities within 30 days after medication changes. Because providers may request a repeat measurement on another day to confirm the elevated SBP, we excluded SBP measures between 141 and 160 mmHg, if there was another value <140mmHg within 7 days. This approach was adapted from two studies which examined treatment intensification.10, 11 Using these criteria, 7 patterns of care emerge (Supplemental Table I). The rules were designed to replicate clinical practice and prevent overestimating opportunities while maximizing “credit” given to practitioners.

Medication adherence

Medications in the adherence assessment included the following classes: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or receptor blocker; beta-blocker; diuretics (except furosemide); calcium channel blocker; centrally acting antihypertensive or alpha adrenergic antihypertensives. Furosemide was excluded given the potential for “as needed” use.11

Medication adherence was computed using the medication possession ratio (MPR) defined by Steiner and colleagues as a continuous, multiple-interval measure of medication availability.12, 13 An average of all drugs’ MPRs within a therapeutic class was computed to produce one averaged MPR accounting for medication “stockpiling” ; average MPR was then dichotomized with non-compliance defined as <0.8.14 We calculated for each patient an MPR as the ratio of the number of days with antihypertensive available divided by the medication eligible days.13, 15, 16 The MPR ranges from 0 to 1, and higher values indicate greater adherence. For patients with 0 or 1 antihypertensive medication fill, their MPR was considered missing.

Statistical Analyses

Covariates were chosen based on clinical significance and included: sex, race (white, black, other), number of antihypertensives prescribed at the index stroke, NIH stroke scale17 and Charlson co- morbidity score.18 We accounted for clustering of patients within medical centers because of the correlation of outcomes (level of hypertension control among patients from the same facility).

We used a mixed-effects regression model to examine the average SBP trajectory of all patients from stroke discharge over the 1-year post stroke stratified by their last SBP at discharge (<140mmHg; 141 mmHg to < 160 mmHg; and >160 mmHg). Then we analyzed treatment intensification among patients who had at least one elevated SBP (treatment opportunity) over the 1 year post stroke follow-up. For these analyses, we excluded patients with controlled SBP during the follow-up period (no treatment opportunities). We used linear regression to examine the association between adherence (MPR) and treatment intensification. Statistical analyses were done using SAS for Windows 9.2. (SAS Institute, Cary, NC)

RESULTS

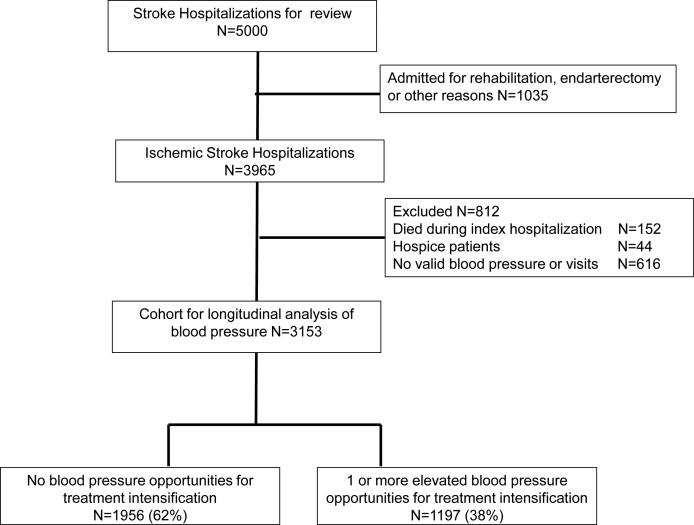

Of the 3965 ischemic stroke patients, we excluded cases (N=812 [20.4%]) for: in hospital mortality (N=152), hospice care (N=44) or no SBP values (N=616, Figure 1). Sixty two percent (N=1956) of the 3153 patients in the sample had no opportunities for treatment intensification because SBP was <140mmHg in the year after stroke. The remaining patients (N=1197) had at least one elevated SBP or a treatment intensification opportunity. Patients in both groups were 65 years-old and the majority were male (Table 1). Patients without treatment intensification opportunities did not differ in age, NIH stroke scale, Charlson score or smoking status compared with those who had one or more intensification opportunities. A higher proportion of black patients (27.2%) had at least one intensification opportunity during follow-up versus those with no opportunities (20.6%).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by whether opportunity for treatment intensification existed during the follow-up (N=3153)

| No blood pressure Opportunity N=1956 | At least one blood pressure opportunity N=1197 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex Males (%) | 98.0 | 97.6 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 65.0 (58.0, 76.0) | 65.0 (58.0, 75.0) |

| < 65 years, (%) | 49.3 | 49.7 |

| 65 - 74 years, (%) | 22.3 | 24.1 |

| 75 + years, (%) | 28.4 | 26.2 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 65.0 | 58.5 |

| Black | 20.6 | 27.2 |

| Other | 6.9 | 7.3 |

| Missing race | 7.5 | 7.0 |

| NIH stroke scale (%) | ||

| 0-2 | 53.5 | 53.72 |

| 3-9 | 38.2 | 41.19 |

| 10 + | 8.3 | 5.10 |

| Current Smoker (%) | 37.3 | 37.0 |

| Charlson Score (mean ±SD) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (1, 2) |

| Antihypertensives at discharge, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) |

| Antihypertensive Class (%) | ||

| None | 9.6 | 5.2 |

| ACE/ARB | 26.0 | 26.2 |

| Alpha-1 Antagonist | 3.8 | 3.1 |

| Beta Blocker | 22.8 | 22.4 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 12.0 | 14.6 |

| Loop Diuretics | 6.5 | 6.1 |

| Other antihypertensives | 9.3 | 10.1 |

| Other Diuretic | 10.1 | 12.2 |

| Discharged to home (%) | 68.6 | 69.8 |

BP trajectory in the year after stroke

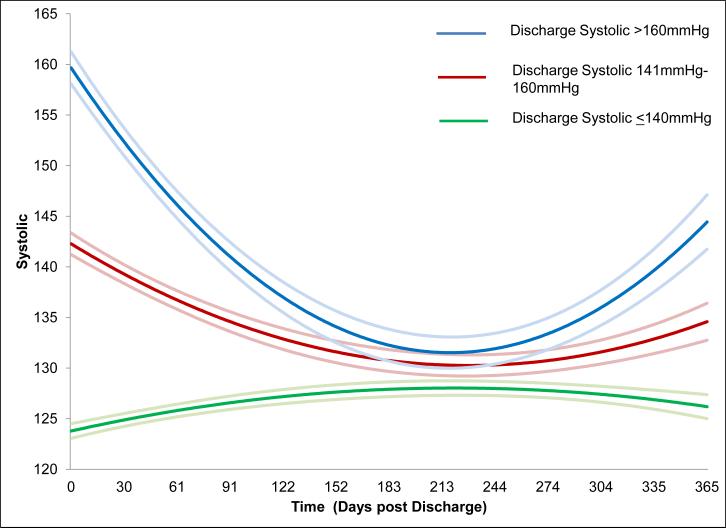

Among the 3153 patients who were discharged from an ischemic stroke hospitalization; 1973 (62.6%) had a discharge SBP < 140mmHg, 819 patients (26.0%) with SBP between 141 and 160mmHg, and 361 patients (11.4%) with SBP >160mmHg (Table 2). The average SBP and DBP increased among each of these three groups, with no difference in the average number of clinic visits (mean 4.7, SD 3.8 p=0.18). When adjusted for covariates, the discharge SBP strongly influenced SBP trajectory over the following year (Figure 2).

Table 2.

1-Year Follow-Up mean blood pressure, clinic visits and number of medications among ischemic stroke patients stratified by discharge blood pressure.

| Clinical Measures in the Year post-stroke | Blood pressure at hospital Discharge Full cohort N=3153 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <140 mmHg N=1973 (62.6%) | 141-160 mmHg N=819 (26%) | > 160 mmHg N=361 (11.4%) | P value | |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg mean (SD) | 126.1 (11.9) | 136.8 (11.0) | 146.5 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg mean (SD) | 72.9 (9.9) | 74.1 (9.9) | 75.6 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Number of Outpatient Clinic visits* Mean (SD) | 4.6 (4.1) | 4.7 (3.8) | 4.9 (3.6) | 0.1850 |

| Antihypertensive Drugs at Discharge, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (2, 4) | <0.001 |

| Patients with at least one elevated blood pressure opportunity post discharge N (%) | 590/1973 (30%) | 381/819 (46.5%) | 226/361 (62.6%) | <0.001 |

Eligible clinic visits include: general internal medicine; primary care/medicine; women's health; mental health primary care; geriatrics; hypertension; cardiology; anticoagulation; diabetes, endocrine, or metabolism; infectious disease; renal/nephrology; pulmonary, or chest; or neurology.

Figure 2.

Systolic blood pressure trajectory in the year post stroke.*

*Quadratic model adjusted for sex, race, Charlson score, number of antihypertensive drugs at discharge, and interactions for discharge blood pressure by time

Treatment Intensification among those with Elevated SBP

There were 1197 patients with at least one elevated SBP who had on average 6 clinic visits during follow-up. Thirty percent of patients discharged with a SBP <140mmHg had an average 1.93 opportunities for medication intensification. Forty seven percent of patients with discharge SBP between 141 and 160mmHg had an average of 2.1 opportunities for intensification and 63% of patients with a discharge SBP >160mmHg had an average of 2.4 intensification opportunities. Because the number of medication intensifications also increased; the proportion of clinically appropriate treatment intensifications was similar between the three categories, ranging from 58 to 65% (p=0.15). In other words, in about one-third of visits with elevated SBP, there was no evidence that medications were intensified. (Table 3)

Table 3.

1-Year Follow-Up for patients with at least 1 elevated blood pressure opportunity by discharge blood pressure (n=1197).

| Characteristics in the year after stroke | <140 mmHg N=590 | 141-160 mmHg N=381 | > 160 mmHg N=226 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg mean (SD) | 137.5 (8.9) | 143.5 (9.7) | 151.0 (12.3) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg mean (SD) | 78.4 (9.8) | 77.7 (9.6) | 78.4 (10.6) | 0.519 |

| Number of Antihypertensives, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 3 (2, 4) | <0.001 |

| Number of Eligible clinic visits*, mean (SD) | 5.8 (5.4) | 5.8 (4.6) | 5.8 (3.8) | 0.987 |

| Antihypertensive Intensifications | ||||

| Median IQR | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.003 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.13 (1.11) | 1.23 (1.11) | 1.46 (1.27) | <0.001 |

| Intensification opportunities | ||||

| Median IQR | 1 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.93 (1.54) | 2.12 (1.45) | 2.39 (1.64) | <0.001 |

| Proportion of Intensifications to opportunities | ||||

| Mean (95% Confidence Interval) | 58% (55, 62) | 60% (55, 64) | 65% (59, 70) | 0.150 |

| Proportion with calculable Pre stroke Medication Possession Ratio (%) | 492/590 (83.4) | 325/381 (85.3) | 187/226 (82.7) | 0.641 |

| Medication possession ratio, mean (SD) | 0.74 (0.23) | 0.73 (0.23) | 0.75 (0.21) | 0.725 |

| Medication possession ratio >0.8 (%) | 47.8 | 47.1 | 49.7 | 0.905 |

| Proportion with calculable Post stroke Medication Possession Ratio (%) | 573/590 (97.1) | 364/381 (95.5) | 219/226 (96.9) | 0.399 |

| Medication possession ratio, mean (SD) | 0.74 (0.20) | 0.76 (0.18) | 0.76 (0.19) | 0.190 |

| Medication possession ratio >0.8 (%) | 46.4 | 45.6 | 46.6 | 0.963 |

| Pre-stroke/Post-stroke comparison† | 0.937 | 0.047 | 0.944 |

Eligible clinic visits include: general internal medicine; primary care/medicine; women's health; mental health primary care; geriatrics; hypertension; cardiology; anticoagulation; diabetes, endocrine, or metabolism; infectious disease; renal/nephrology; pulmonary, or chest; or neurology.

Comparison of pre versus post stroke medication possession ratio p value reported

Relationship between adherence and treatment intensification

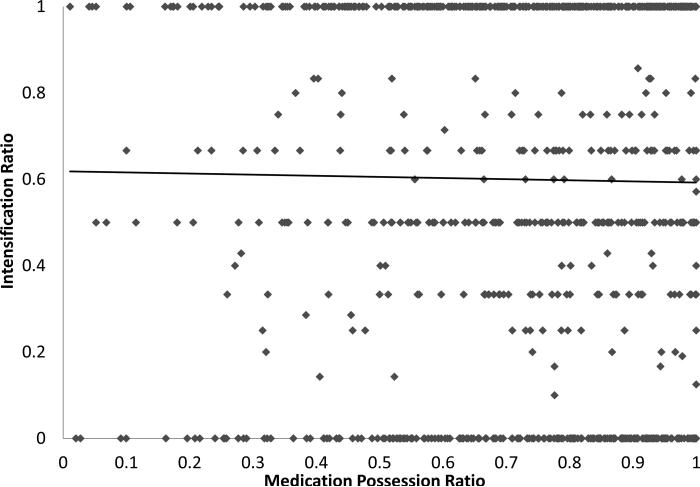

Among patients with at least one intensification opportunity, approximately 48% were adherent (MPR >0.8) to their anti-hypertensive medications in the pre-stroke period and 46% were adherent in the post-stroke period. Alternatively, among those with an elevated SBP, more than 50% had an MPR <0.8 (indicating low adherence). There was no statistical difference in average MPR or in the proportion considered adherent across the three groups based on discharge SBP (Table 3). No relationship between medication adherence and treatment intensification ratio was detected (p=0.71, Figure 3). Patients with an MPR of 1 (excellent adherence) had a treatment intensification ratio of 0% (indicating no medication changes). Similarly, patients with an MPR of <0.3 (poor medication adherence) had treatment intensification ratios of 100% (every elevated SBP resulted in a medication change).

Figure 3.

Medication possession ratio (adherence) and relationship to treatment intensification*

*Relationship between adherence and treatment intensification p= 0.71.

DISCUSSION

We report three main findings. First, among patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke, SBP trajectory post stroke was highly influenced by discharge SBP. Second, regardless of discharge SBP, the ratio of medication intensification to opportunities is 58 to 65%. An alternate interpretation is that we did not see evidence of medication titration in 35-42% of visits among post-stroke patients with elevated SBP values. Third, there was no relationship between post stroke medication adherence and treatment intensification evidenced by the ~50% of patients with an elevated SBP in the post stroke period had an adherence level of <80%. This finding suggests that many patients would benefit from adherence counseling and that often providers do not account for or assess adherence when deciding to intensify treatment.

Our results prompt three modifiable targets for improvement in stroke care. Deficiencies in delivery of secondary prevention are common after cerebrovascular events.19-21 Hospital initiation of secondary prevention strategies is the standard of care for acute cardiac conditions and can improve risk factor control.22 As a result, the 2014 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack emphasized initiation or resumption of hypertension treatment after the acute stroke period (24 to 48 hours) in neurologically stable patients with documented blood pressures of >140/90 mmHg .5 Increased efforts to improve hypertension management prior to discharge (including re-initiation or modification of antihypertensives) could be highly beneficial to patients, given the robust relationship between discharge SBP and SBP trajectory post stroke in this study.

Second, efforts to assure that patients are on the correct medications and to titrate those medications should be implemented to avoid untreated/ undertreated hypertension. At particular risk are those with resistant hypertension or black patients who are both more likely to be uncontrolled in the post stroke period, and may not have their medications changed or titrated.8, 23 The lack of treatment intensification which we report are similar to those reported by Heisler et al.11 These investigators studied 38, 327 Veterans with hypertension; treatment intensification occurred at 30% of 68,610 elevated BP visits. While we observed higher proportion of intensifications (58-65%), these investigators also found no relationship between intensification and medication adherence. Another study by Rose et al.24 evaluated 819 patients with hypertension over 2 years. They reported that adherent patients received more treatment intensification (approximately one intensification every 11 visits) compared to non- adherent patients. However, patients with the worst adherence generally took approximately half their medication and any intensification resulted in blood pressure reductions. Nevertheless, clinicians should assess a patients’ medication taking behavior and their self-efficacy for using medication at each treatment intensification decision.

Finally, programs to improve anti-hypertensive medication adherence should be implemented. Many patients are discharged with instructions that include—“resume home regimen”. This home regimen is never revisited or modified despite the new risk factor of ischemic stroke. Additional counseling on adherence and evaluation of new barriers that may exist because of limitations resulting from the stroke should be addressed. All of the above issues are preliminary steps in understanding and optimizing risk factor management among stroke patients.

There are limitations to our study. First, the population was mostly male Veterans admitted with ischemic stroke. Hypertension management in the post-stroke period may not reflect the management of the general population. However, we do not believe that providers in the private sector are systematically more or less aggressive in hypertension management than VHA providers.25-27 Our sample included persons with milder strokes and those discharged home; therefore our results may be more generalizable to this population. It is also possible many patients received their antihypertensive care outside VHA, or that our treatment intensification algorithm missed patients with reasons for not intensifying therapy such as orthostatic hypotension. Similarly, we did not extensively review charts to determine if after discussion, patients and providers chose not to titrate medications (because of medication burden, dietary non adherence or patient-centered reasons). Our intensification algorithms missed ~ 20% of the treatment intensifications in which the provider told the patient to increase their dose. This study was not designed to evaluate the appropriateness of the medication regimen nor whether patients had received comprehensive evaluations for the etiology of their hypertension (measurement of renin, aldosterone, or diagnostic testing such as renal artery imaging.) Finally we utilized refill data as a proxy for medication taking and to calculate adherence.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

SBP improves in the year after stroke; however, 12% of patients were discharged with SBP>160mmHg and many remained high in the year post stroke. This population had no statistically significant difference in treatment intensification compared to patients who were discharged with lower SBP. This finding suggests that the place to affect the most change in the post stroke BP trajectory is prior to discharge. Interventions to systematically improve modifiable risk factors should span inpatient and outpatient spectrum to deliver optimal patient care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Health Services Research and Development (HSRD)(STR 03-168 and RRP 11-267; Research Career Development Award, Zillich RCD 06-304-1); VHA Clinical Science Research and Development (Roumie I01CX000570-01) and NIH/ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U54NS081764 (Cheng)

Footnotes

Disclaimer The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Hong KS, Yegiaian S, Lee M, Lee J, Saver JL. Declining stroke and vascular event recurrence rates in secondary prevention trials over the past 50 years and consequences for current trial design. Circulation. 2011;123:2111–2119. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rashid P, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath P. Blood pressure reduction and secondary prevention of stroke and other vascular events: A systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:2741–2748. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000092488.40085.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, McGee DL, Dawber TR, McNamara P, Castelli WP. Systolic blood pressure, arterial rigidity, and risk of stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1981;245:1225–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bushnell CD, Zimmer LO, Pan W, Olson DM, Zhao X, Meteleva T, et al. Persistence with stroke prevention medications 3 months after hospitalization. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1456–1463. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reker DM, Hamilton BB, Duncan PW, Yeh SC, Rosen A. Stroke: Who's counting what? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JS, Arling G, Ofner S, Roumie CL, Keyhani S, Williams LS, et al. Correlation of inpatient and outpatient measures of stroke care quality within veterans health administration hospitals. Stroke. 2011;42:2269–2275. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.611913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roumie CL, Ofner S, Ross JS, Arling G, Williams LS, Ordin DL, et al. Prevalence of inadequate blood pressure control among veterans after acute ischemic stroke hospitalization: A retrospective cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:399–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arling G, Reeves M, Ross J, Williams LS, Keyhani S, Chumbler N, et al. Estimating and reporting on the quality of inpatient stroke care by veterans health administration medical centers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:44–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose AJ, Berlowitz DR, Manze M, Orner MB, Kressin NR. Comparing methods of measuring treatment intensification in hypertension care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:385–391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.838649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heisler M, Hogan MM, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, Pladevall M, Kerr EA. When more is not better: Treatment intensification among hypertensive patients with poor medication adherence. Circulation. 2008;117:2884–2892. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: Methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry-Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health. 2007;10:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner JF, Koepsell TD, Fihn SD, Inui TS. A general method of compliance assessment using centralized pharmacy records. Description and validation. Med Care. 1988;26:814–823. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner JF, Robbins LJ, Roth SC, Hammond WS. The effect of prescription size on acquisition of maintenance medications. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:306–310. doi: 10.1007/BF02600143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams LS, Yilmaz EY, Lopez-Yunez AM. Retrospective assessment of initial stroke severity with the NIH stroke scale. Stroke. 2000;31:858–862. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, MacKenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudd AG, Lowe D, Hoffman A, Irwin P, Pearson M. Secondary prevention for stroke in the United Kingdom: Results from the national sentinel audit of stroke. Age Ageing. 2004;33:280–286. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu G, Liu X, Wu W, Zhang R, Yin Q. Recurrence after ischemic stroke in chinese patients: Impact of uncontrolled modifiable risk factors. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;23:117–120. doi: 10.1159/000097047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan RC, Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT, Jr., Manolio TA, Heckbert SR, Lefkowitz D, et al. Vascular events, mortality, and preventive therapy following ischemic stroke in the elderly. Neurology. 2005;65:835–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176058.09848.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giugliano RP, Braunwald E. 2004 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with STEMI: The implications for clinicians. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2:114–115. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard G, Prineas R, Moy C, Cushman M, Kellum M, Temple E, et al. Racial and geographic differences in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Stroke. 2006;37:1171–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217222.09978.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose AJ, Berlowitz DR, Manze M, Orner MB, Kressin NR. Intensifying therapy for hypertension despite suboptimal adherence. Hypertension. 2009;54:524–529. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aslam F, Haque A, Agostini JV, Wang Y, Foody JM. Hypertension prevalence and prescribing trends in older us adults: 1999-2004. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 12:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bromfield SG, Bowling CB, Tanner RM, Peralta CA, Odden MC, Oparil S, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among us adults 80 years and older, 1988-2010. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014;16:270–276. doi: 10.1111/jch.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.