Introduction

There are over four million live births each year in the United States. Nearly 800,000 — or 20% — of these mothers will experience an episode of major or minor depression within the first three months postpartum (Marcus, Flynn, Blow, & Barry, 2003). This makes depression the most common complication of childbearing (Grace, Evindar, & Stewart, 2003), far above both gestational diabetes (3-8%) (Dabelea et al., 2005) and preterm birth (12.3%) (Saigal & Doyle, 2008). Maternal depression affects the entire family; it is associated with marital discord and impaired occupational and social functioning, as well as with maternal–infant interactions characterized by disengagement, hostility, and intrusion (Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 1998) (Grace et al., 2003). (Kurstjens & Wolke, 2001). Moreover, studies have consistently demonstrated the deleterious effects of postpartum depression (PPD) on cognitive and emotional development during infancy and later childhood (Zhu et al., 2014; Conroy et al., 2012).

Researchers are only at the beginning stages of discovering biological factors that may contribute to the etiology of postpartum depression, but there are numerous known psychological and social risk factors. Previous meta-analyses have identified fifteen: (1) lower social class, (2) life stressors during pregnancy, (3) complicated pregnancy/birth, (4) difficult relationship with family or partner, (5) lack of support from family or friends, (6) prior history of psychopathology (depression, anxiety), (7) chronic stressors postpartum (this can include problems with child care and difficult infant temperament), (8) unemployment/instability, (9) unplanned pregnancy, (10) ambivalence over becoming a pregnant, (11) poor relationship with own mother, (12) history of sexual abuse, (13) lack of a confidante, (14) bottle feeding, and (15) depression during pregnancy, with the last generally acknowledged to be the strongest predictor of PPD (Beck 2001; O’Hara and Swain, 1996; Richards, 1990; and Seguin et al., 1999). Recent research on the biological risk factors includes studies on oxytocin (Skrundz et al., 2011) and inflammatory markers (Osborne & Monk, 2013).

Postpartum depression is significantly undertreated. Many women feel that depression at what “ought” to be a joyful time is shameful, and others are influenced by society’s general stigma concerning mental health care. In addition, those women who do seek treatment often hesitate to take psychotropic medications when breastfeeding, despite substantial evidence of their relative safety (Beck, 2001) (Goodman, 2009) (Cott and Wisner, 2003, Freeman, 2007).

Given the public health relevance of PPD, its well–characterized psychological risk factors, and the substantial barriers to care once women become ill, a focus on the prevention of PPD holds tremendous potential for clinical efficacy. In particular, prospective mothers are especially motivated for self-care (Kost et al, 1998), and are already in frequent contact with health care providers (Tatano Beck, 2001). Here we offer a critical review of existing approaches to PPD prevention, with the dual aim of identifying effective treatment components across many modalities and identifying treatment gaps that may be amenable to novel interventions.

Methods

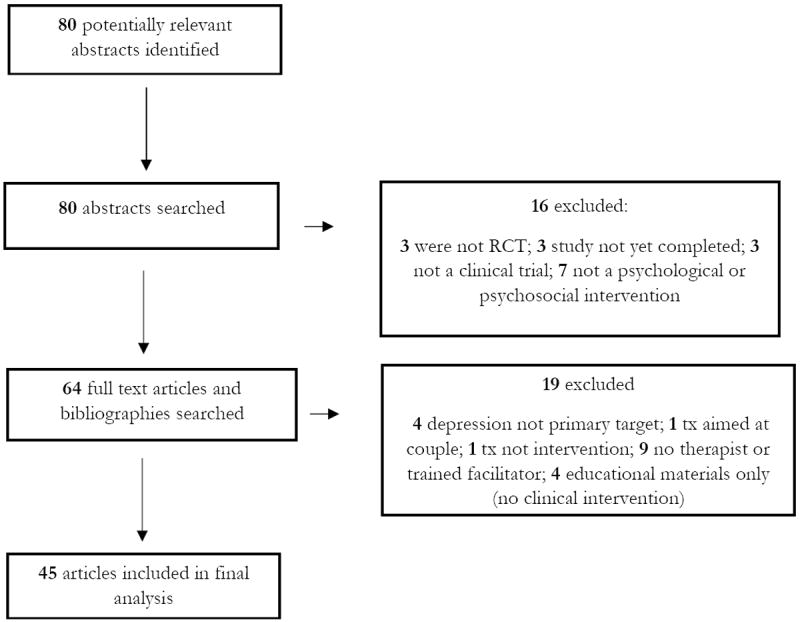

The literature review began with a PubMed search conducted by two authors (Werner and, Miller, both doctoral-level clinical psychologists with specialized perinatal research training) and completed in April 2013. Fig. I contains a flow-chart outlining the search strategy. The search was limited to peer-reviewed, published, English-language, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of biological, psychological, and psychosocial interventions. Moreover, only studies of methods of prevention of PPD (rather than those designed to examine a treatment for PPD) were included. To be included, studies needed to have some therapeutic component (at least one individual or group session with a therapist or trained facilitator). Studies that covered interventions that were purely educational (i.e., booklet or video with no human intervention) as well as those delivered by primary care practitioners without specialty training were excluded, chiefly because of space constraints. The search was not limited by date of publication, sample size, or whether the full text was available online. Four separate searches were combined, using the terms (1) prenatal, pregnancy, pregnant, antenatal, postnatal, postpartum, perinatal; (2) depression, mood; (3) prevention; and (4) intervention. 80 potential articles were identified. Abstracts were reviewed by Werner and Miller and 16 did not meet inclusion criteria and were eliminated. Werner and Miller then reviewed full text of the remaining 64 articles, and reference sections of these articles were cross-checked for additional material. After full-text review, an additional 19 articles did not meet inclusion criteria. A total of 45 trials were identified that met inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure I.

Flow chart of study

The articles reviewed use a variety of screening instruments to identify risk. Each instrument generates a score on a particular scale; when a participant scores at or above a cut-off point, risk of clinically significant depression is assumed to be present. The performance (sensitivity and specificity) of each instrument depends critically on the cut-off point chosen. The three most commonly used are the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Predictive Index for Postpartum Depression (PIPD). The EPDS [Cox et al., 1987], was developed to assess symptoms of PPD, and the CES-D was designed as a screening tool for determining the severity level of depression symptoms. They are commonly used to determine risk for PPD. Their predictive value, when administered during pregnancy, is likely related to the fact that prenatal depression serves as a strong predictor of PPD (Beck et al., 1996); Eberhad-Gran et al, 2001; Radloff, 1977; Thomas et al, 2001). The PIPD, a 17-item risk survey developed and validated by Cooper et al. (1996), is a screening instrument specifically designed to predict PPD. The specificity and sensitivity of this scale are limited, and at a score of 27 or more (score range = 0 – 63), the risk of postpartum depression is reported to be 35%; more than a third of those who went on to develop PPD scored in this range (Cooper et al., 1996).

In addition to using a variety of screening measures, the relevant studies had important differences in their subject populations. Some studies drew from the general population of healthy pregnant women, while others defined an “at risk” or “high risk” group, the definition of which varied; we have included information about the population in our discussion of each study. Moreover, not all studies screened for depression during pregnancy (prior to the intervention), which raises the possibility that the interventions were actually treating, rather than preventing, a depression that began in pregnancy and continued postpartum, which may be an etiologically distinct subtype from postpartum onset (PPD). We have accordingly indicated those studies that did not screen for depression in pregnancy. In addition, while we have listed (see Table I) all studies that met our criteria, we highlight certain studies that are particularly illustrative of the approaches to, and challenges of, preventing PPD.

Table 1.

Summary of results

| Citation and Country | Participants and method of recruitment | Intervention and delivery (including administering clinician) | Control group | Screening measures for depression | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS | ||||||

| Wisner et al (2004), United States | 22 postnatal, nondepressed women in general population with at least one previous episode of PPD. | Sertraline administered as soon as possible post-delivery | Placebo | Hamilton Depression sand SCID-IV (Hamilton score = 15 for depression evaluation) | Placebo group significantly more likely to experience PPD recurrence (p = .04). Intervention group had significantly longer time before recurrence (p = .02). | Data excluded from 3 women in intervention group who declined to take medication |

| Lawrie et al (1998), South Africa | 80 postnatal women in general population using non-hormonal contraception | Norethisterone enanthate administered 48 hrs post-delivery | Placebo | Montgomery- Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and EPDS (MADRS score>18 and >9 used to evaluate women for major and minor depression) | Intervention group scored significantly higher on MADRS at delivery (p=.0111) and EPDS 6 weeks postpartum (p = .0022) | Study examined potential PPD risk factor, not prevention intervention. No cutoff scores given for EPDS |

| Llorente et al (2003), United States | 89 postpartum, breastfeeding women in general population | DHA administered beginning one week post-delivery for 4 months | Placebo | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI >10 for evaluating mild depression, >20 for evaluating moderate depression) | No significant difference between groups (p<.35) | Micronutrient supplementation limited to DHA |

|

Doornbos et al (2009) Holland |

119 women 14-20 weeks pregnant in general population | DHA or DHA and AA (arachidonic acid), administered from pregnancy until 3 months post-delivery | Placebo | EPDS (EPDS> 13 for evaluating depression) | No significant differences between groups (p=.969) | |

|

Makrides et al (2010) Australia |

2399 women > 21 weeks’ gestation in general population | 800 mg/day DHA | Placebo | EPDS (EPDS >12 for evaluating depression) | No significant difference between groups (p=.09) | |

|

Mokhber et al. (2011) Iran |

166 Pregnant, primiparous women in general population | 100ug selenium yeast given daily from first trimester to delivery | Placebo | EPDS (EPDS>13 for evaluating depression) | Treatment group had significantly lower EPDS scores (p <.05) | |

|

Harrison-Hohner (2001) United States |

247 nulliparous women, 11-21 weeks gestation in general population | Elemental calcium administered daily throughout pregnancy | Placebo | EPDS (EPDS ≥14 for depression evaluation) | Intervention group significantly less likely to experience severe PPD (p=.014) | Study intended to test calcium as a prevention for preeclampsia: PPD finding ancillary |

| Harris et al (2002) | 446 pregnant, Thyroid-antibody-positive women | Thyroxine, administered daily from six-24 wks postpartum | Placebo | EPDS, MADRS, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (cutoff scores for evaluating depression = 15, 13, 8, respectively) | No significant difference between groups | |

| INTERPERSONAL THERAPY | ||||||

|

Zlotnick et al (2001) United States |

37 pregnant women with at least one risk factor for PPD | 4, 60-minute IPT (interpersonal therapy) group sessions, administered during pregnancy (ROSE program) | Treatment as usual | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), SCID (BDI change > 1.96 used to evaluate intervention effectiveness) | Change in Beck scores significantly higher for intervention group (p = 0.001) | Survey to determine risk factor for PPD relatively new, intervention ended at delivery, small n, group intervention sessions |

|

Zlotnick et al (2006) United States |

99 pregnant, low-income women at risk for PPD (PIPD score >=27) | ROSE program plus individual postpartum booster | Treatment as usual | Predictive Index for Postpartum Depression (PIPD), BDI, Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation | Significantly fewer women in intervention group developed PPD (p=.04) | Group intervention sessions, no BDI cutoff given for evaluating depression |

|

Zlotnick et al (2011) United States |

54 low-income pregnant women reporting intimate partner violence in past year | 4 60-minute IPT sessions over 4 weeks, 1 60-minute postpartum session | Treatment as usual | EPDS, LIFE (longitudinal Interview Follow-up Examination)inte rview (LIFE score = 5 or 6 indicates diagnosis) | No significant difference between groups (p=.57) | No EPDS cutoff score given for evaluating depression |

|

Crockett et al (2008) United States |

36 pregnant, African American women on public assistance who are at risk for PPD (PIPD score >=27) | ROSE program plus individual postpartum booster | Treatment as usual | PIPD, EPDS (EPDS>10 used to evaluate depression) | No significant difference between groups (p=.570) | Group intervention sessions |

| Phipps et al (2011) United States |

106 primiparous, pregnant adolescents from general population | 5, one-hour prenatal IPT sessions, postpartum booster session | Attention and dose-matched control | KID-SCID | No significant difference between groups (p=.1) | Small N |

|

Grote et al (2009) United States |

53 pregnant, low income women at risk for PPD (PIPD score >12) | 9 antenatal interpersonal therapy sessions, monthly maintenance sessions until 6 wks postpartum | Treatment as usual | EPDS, SCID (EPDS>10 used to evaluate depression) | Significant reductions in SCID (p<.00, p<.005) and EPDS (p<.001, p<.001) before birth and at 6 months for intervention group | |

|

Gao et al (2010) China |

194 nulliparous, pregnant women in general population | 2 antenatal psychoeducation classes, telephone follow-up 2 wks post-delivery | Treatment as usual | EPDS, GHQ, Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationships Scale (SWIRS) (EPDS >12, GHQ > 3 used to evaluate depression) | Significantly lower EPDS score in intervention group at 6 wks (p=.000) | Group intervention sessions |

| COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY | ||||||

|

Chabrol et al (2002) France |

241 postpartum women at risk for PPD (EPDS score >9) | 1 individual CBT-based prevention session 2-5 days postpartum | Treatment as usual | EPDS, HDRS, BDI (EPDS>11 for evaluating depression) | Significantly lower EPDS score in intervention group at 4-6 wks postpartum (p=.0067) | Low qualifying EPDS score |

| Cho et al (2008), Korea | 27 pregnant women at risk for PPD (BDI score >16) | 9 individual CBT sessions during pregnancy | One psychoeducational session during pregnancy | BDI (BDI >16 used for evaluating depression) | Intervention group had significantly lower rate of PDD (p<.01) | |

| Milgrom et al (2010) Australia |

143 pregnant women at risk for PPD (EPDS/RAC score ≥13) | CBT-based workbook, 8 weekly individual CBT-based sessions | Treatment as usual | EPDS, BDI-II, Risk Assessment Checklist (RAC) (EPDS/RAC>13, BDI>14 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group had significantly lower BDI-II at 12 wks postpartum (p<.01) | |

|

Tandon et al (2011) United States |

61 low-income pregnant and postpartum women at risk for PPD (CES-D score ≥16, one lifetime depression episode) | 6-session weekly CBT-based group session | Home visits, information regarding perinatal depression | CES-D, Maternal Mood Screener (MMS), BDI (CES-D≥16, BDI>20 used for evaluating depression) | Intervention group had significantly MMS score 3 months postpartum (p<.05) | Population included both pregnant and postpartum women, clinical cutoff for MMS not reported |

|

Mao et al (2012) China |

240 pregnant, primiparous women in general population | Emotional Self-Management Group Training (ESMGT), 4 weekly group session, one individual counseling session | 90-minute, nurse-instructed childbirth classes | Patient Health questionnaire 9 PHQ-9. EPDS, SCID (EPDS>10, PHQ-9>10 used to evaluate depression | Intervention group had significantly lower scores on all three screening measures (p<.01 for PHQ, p<.05 for EPDS and SCID) | |

|

Kozinszky et al (2012) Hungary |

1719 pregnant women in general population | 3-hour group psychotherapeuti c/psychoeducatio nal sessions | Treatment as usual | Leverton Questionnaire (LQ) (LQ≥ 11 used for evaluating depression) | PPD prevalence (as defined by LQ) significantly lower in intervention (p<.01) | |

| Silverstein et al (2001) United States |

50 low-income mothers of preterm infants at risk for PPD | 4 individual, CBT-based, problem-solving sessions | Treatment as usual | Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS) (QUIDS≥11 used for evaluating depression) | No significant differences between groups | Participants not screened for antenatal depression, non-significant p value not reported |

|

Hagan et al (2004) Australia |

199 mothers of preterm or very low birthweight infants not depressed during pregnancy | 1 prenatal debriefing session and 6 weekly 2-hr group CBT sessions | Treatment as usual | Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) | No significant differences between groups | SADS based on DSM criteria, therefore no clinical cutoff |

|

Zayas et al (2004) United States |

187 pregnant minority women at risk for PPD (BDI score >=14) | 8 group CBT sessions, 4 psychoeducation sessions, and social support building from therapist | Treatment as usual | BDI (BDI>14 used to evaluate depression) | No significant differences between groups, | |

|

Austin et al (2008) Australia |

277 pregnant women at risk for PPD (EPDS score >10, ARQ score >23) | 6 weekly, 2-hr group CBT sessions, additional follow-up session | Treatment as usual and information booklet | EPDS, Antenatal Risk Questionnaire (ARQ), Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (EPDS>10, 4 of 5 MINI criteria used to evaluate for depression) | No significant difference between groups (p>.05) | Low qualifying EPDS score |

|

Munoz et al (2007) United States |

41 pregnant, low-income Latina women at risk for PPD (History of MDE, CDS-D score ≥16) | 12 week CBT course, 4 booster sessions | Treatment as usual | CES-D (CES-D≥16 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group clinically less likely to develop MDE (p=0.85) | |

|

Le et al (2011) United States |

217 pregnant, low-income Latina woman at risk for PPD (History of MDE, CDS-D score ≥16) | 8 week CBT course, 3 booster sessions | Treatment as usual | CES-D, BDI (CES-D≥16, BDI≥20 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention had significant short-term effect (p=.03), no long-term effect | Low incidence of depression among both control and intervention groups |

| POSTNATAL PSYCHOLOGICAL DEBRIEFING | ||||||

|

Lavender and Walkinshaw (1998) UK |

120 postnatal women with normal spontaneous vaginal deliveries in general population | Debriefing about experience of labor soon after delivery | Treatment as usual | Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) (HADS>10 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group significantly less likely to have high depression or anxiety on HADS (p= .0001) | Population not at risk for depression, HADS not validated for postnatal care |

|

Gamble et al (2005) Australia |

102 postnatal women who experienced distressing/traumati c birth, at risk for PPD | Debriefing about experience of labor soon after delivery, telephone follow-up | Treatment as usual | EPDS (EPDS>12 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group less likely to develop PPD (p=.002) had significantly lower total PTSD symptom score at 3 months (p=.035) | Interviewers had unspecified training |

| Small et al (2000, 2006) Australia |

1041 postnatal women who had operative births, at risk for PPD | Debriefing about experience of labor soon after delivery | Treatment as usual, informational packet | EPDS (EPDS≥13 used to evaluate depression) | No significant difference between groups (p=0.24) | Interviewers had unspecified training |

|

Tam et al (2003) Hong Kong |

516 postnatal women who experienced “suboptimal outcomes” during pregnancy and delivery, at risk for PPD | Two-part educational counseling sessions (1-4) from two senior research nurses | Treatment as usual | HADS and GHQ (GHQ=4/5 used to evaluate depression) | No overall significant difference between groups, elective C- sections among intervention group less depressed (p=.009) | |

|

Priest et al (2003) Australia |

1730 postnatal women in general population | Single debriefing session 24-72 hrs after delivery | Treatment as usual | EPDS, SADS (EPDS>12 used to evaluate depression) | No significant difference between groups (p=0.58) | |

| ANTENATAL AND POSTNATAL CLASSES | ||||||

|

Elliot et al (200) United Kingdom |

99 pregnant women at risk for PPD (CES-D score ≥ 16) | 11 group sessions (5 during pregnancy, 6 postpartum) | Treatment as usual | CES-D (CES-D ≥ 16 used to evaluate depression) | Significantly lower rate of PPD in tx group for primiparous women only (p>.005) | |

|

Mathey et al (2004) Australia |

268 pregnant women in general population | 6 routine antenatal classes, additional class focused on postpartum psychology |

|

EPDS (EPDS=12/13 used to evaluate depression) | Pts with low self-esteem in intervention had less depression at 6 weeks (measured by Ces-D) (p<.01) | |

|

Lara et al (2010) Mexico |

136 pregnant women at risk for PPD (CES-D score ≥ 16, self-reported previous depression) | 8, 2-hr group counseling sessions during pregnancy sessions, informational packet | Treatment as usual plus informational packet | SCID, BDI-II, CES-D, SCL-90 (BDI-II ≥14, CES-D≥16, SCL-90≥18 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group had significantly lower levels of depression (measured by SCID) (p<.05) | Very high attrition rate in intervention group |

|

Stamp et al (1995) Australia |

144 pregnant women at risk for PPD (PPD vulnerability determined by modified antenatal screening questionnaire) | 2 antenatal group counseling sessions, 1 postpartum group session | Treatment as usual | EPDS (EPDS>12 used to evaluate depression) | No significant difference between groups | High attrition rate in both intervention and control groups, low attendance |

|

Buist et al (1999) Australia |

45 pregnant women at risk for PPD (Risk factor scale >8) | 10 antenatal group counseling sessions during pregnancy | Treatment as usual | BDI, Speilberger Trait/State Anxiety Scale (SAS), Eysenk Personality Inventory (EPI), Sarason Social Support Scale (SSS), Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale (SDA) | No significant difference between groups | Small sample size, some questionnaires not validated, cutoff scores for evaluating depression not reported |

|

Brugha et al (2000) UK |

209 pregnant women at risk for PPD (PPD vulnerability determined by “Pregnancy and You” scale (Brugha et al, 1998)) | 6, 2-hr educational classes during pregnancy | Treatment as usual | GHQ, EPDS, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (presence of 2/6 depression criteria on GHQ used to evaluate depression) | No significant difference between groups | High attrition, low attendance. EPDS and SCAN clinical cutoffs not reported |

|

Hayes et al (2001) Australia |

206 nondepressed, primiparous women in general population | Informational booklet and audiotape and single educational session | Treatment as usual | Profile of Mood States (POMS) | No significant difference between groups | POMS cutoff for evaluating depression not reported |

|

Howell et al (2012) United States |

540 Black and Latina, postpartum women in general population | Two therapy sessions within 2 wks postpartum | Treatment as usual plus list of resources | EPDS (EPDS≥10 used for evaluating depression) | No significant difference between groups by three months (p=.11) | |

| POSTNATAL SUPPORT | ||||||

|

Armstrong et al (1999) Australia |

181 postpartum women at risk for PPD (At least one self-reported first-tier risk factor for “family dysfunction”) | 12 home nursing visits beginning immediately post-delivery | Standard community child health services | EPDS (EPDS>12 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group had significantly lower EPDS at 6 weeks (p<.05), smaller percentage clinical depression in intervention group (p<.05) | |

|

Dennis et al (2009) Canada |

612 postpartum women at risk for PPD (EPDS score >9) | Telephone-based phone support from PPD survivor | Treatment as usual | EPDS (EPDS>9 used to evaluate depression) | Intervention group had significantly lower EPDS at 12 weeks (no effect at 24 weeks) (p<.001) | |

|

Morrell et al (200) United Kingdom |

623 postpartum women at risk for PPD (Personal or family hx of mental illness, score of <24 on Maternity Social Support Scale) | 10 visits from trained support workers | Treatment as usual | Short-Form 36 (SF-36), EPDS | No significant difference between groups | EPDS, SF-36 cutoff scores for evaluating depression not reported |

|

Reid et al (2002) Scotland |

1004 primiparous, postpartum women in general population |

|

Treatment as usual | EPDS, SF-36, SSQ6 (EPDS>12 used to evaluate depression) | No significant difference between groups | |

|

Wiggins et al (2005) United Kingdom |

731 low-SES, postpartum women at risk for PPD |

|

Treatment as usual | EPDS, GHQ | No significant difference between groups | EPDS and GHQ cutoff scores not listed |

Biological Interventions

To date, there have been very few RCTs on the prevention of PPD using biological interventions. Existing studies include treatment with antidepressants, hormones, omega-3 fatty acids, dietary calcium, thyroxine, and selenium, and have met with mixed success.

Psychotropic medications

Only one RCT (Wisner et al., 2004) has evaluated antidepressant medications. This study, a follow-up to a 2001 open-label trial by the same group of nortriptyline vs. monitoring, was started within 24 hours of delivery in non-depressed women with a history of at least one episode of PPD. Twenty-two women were randomized at parturition to a 17-week trial of sertraline or placebo. The researchers found that sertraline was significantly more effective than placebo at preventing recurrence of depression (as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) for DSM-IV; p=.04). Moreover, the length of time to recurrence (when PPD did develop) was significantly greater in the medication group (p=.02). Of note, the study excluded data from three women in the intervention group who opted not to take the medication.

Reproductive Hormones

Estrogen and progesterone levels fluctuate dramatically during the perinatal period, increasing tenfold during pregnancy and returning to pre-pregnancy levels within 72 hours of delivery (Bloch et al., 2003). This rapid hormonal decline is thought to contribute to PPD in vulnerable women, although a consistent link between hormone levels and PPD has yet to be demonstrated (Bloch et al., 2003). High-dose estrogen (studied in an open-label trial by Sichel et al., 1995, in which it was found to improve the rate of relapse among women with a history of PPD), may be one promising direction, but only one RCT has evaluated hormone administration as a prevention for PPD. In a double-blind trial of 180 South African women in the general population who were not screened for antenatal depression, Lawrie et al. (1998) showed that women who were randomized to an intramuscular injection of 200mg norethisterone enanthate (a common progestogen contraceptive) within 48 hours of delivery had significantly higher scores on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and EPDS at six weeks postpartum than women in the placebo group (p=.0111 and p=.0022, respectively).

Micronutrients

The efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention of PPD has been investigated in three published RCTs. In a study of US women in the general population (N=89), Llorente and colleagues (2003) randomized breastfeeding women to 200mg DHA versus placebo for four months, beginning one week after delivery. No significant differences were found between placebo and treatment groups on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) at the four-month follow up visit. Doornbos et al. (2009) randomized 119 Dutch women in the general population to receive DHA (220mg), DHA and AA (arachidonic acid; 220mg of each), or a placebo daily, from enrollment (14 to 20 weeks pregnant) until three months post-delivery. There were no significant differences among EPDS scores of the three groups at 16 or 36 weeks gestation or at six weeks postpartum, nor in the scores on a maternal blues questionnaire administered within one week postpartum. Finally, Makrides et al. (2010) randomized 2399 Australian women who were less than 21 weeks’ gestation to either an intervention group, which received 800 mg/day of DHA, or a control group, which received a daily placebo, from study entry to birth. There was no significant difference between the DHA and control groups in the percentage of women with high levels of depressive symptoms (EPDS score >12) during the first 6 months postpartum (p=.09).

Other biological agents

Three studies have evaluated the efficacy of alternative biological approaches to preventing PPD: thyroxine, dietary calcium, and selenium. None of the groups chose its sample based on risk for PPD; the selenium trial screened subjects for antenatal depression using the BDI and excluded those scoring >=31 (indicative of moderate to severe depression on the BDI), while the other two did not screen for antenatal depression. Harrison-Hohner and colleagues (2001), analyzing data from a larger US two-site trial evaluating calcium as a preventive measure for pre-eclampsia, found that women given 2000mg calcium daily during pregnancy and the postpartum period had a significantly lower incidence of severe PPD, as defined by an EPDS score ≥ 14, than the placebo group at 12 weeks postpartum (n=247; p=.014). In contrast, Harris and colleagues (2002), in a study of 446 (analyses done of 342) thyroid-antibody-positive pregnant women, found no evidence that 100ug thyroxine administered daily to the subjects from six to 24 weeks postpartum had an effect on the incidence of depression as compared to women in the placebo group. Mokhber et al. (2011), in a study of 166 primipara in Iran, found that women given 100ug of selenium daily (as selenium yeast) from their first trimester through delivery had significantly lower EPDS scores (p<.05), as measured within the first 8 weeks after delivery, than women in the control group, who received daily matching placebo yeast tablets.

In summary, out of eight RCTs of biological interventions for the prevention of PPD, three found a positive effect (Harrison-Hohner et al., 2001, for calcium; Wisner et al., 2004, for sertraline; Mokhber et al., 2011, for selenium), four found no effect (Harris et al., 2002, for thyroxine; Llorente et al., 2003, for omega-3s; Doornbos et al., 2009, for omega-3s; Makrides et al., 2010, for DHA), and one found a negative effect (Lawrie et al., 1998, for progestogen). Based on these results, anti-depressants and nutrients both hold promise for prevention, thought this does not rule out other biological pathways due to a paucity of evidence. Even the three clearly negative studies of omega-3s do not rule out further research in this area because they tested only DHA and AA, while the commonly used formulation for clinical mood symptoms is DHA combined with EPA. It should also be noted that few of these studies selected women at risk for PPD based on known risk factors, which might have diminished the likelihood of finding effects for the interventions.

Psychological and Psychosocial Methods of PPD Prevention

In contrast to the scant data on biological interventions, there have been numerous studies of psychological and psychosocial preventive interventions for PPD. These studies are difficult to compare, as they vary widely in terms of screening and outcome measures, training of personnel/clinicians, dosages of treatment, timing of the initiation of treatment (during pregnancy or postpartum), and follow-up times.

Psychological Interventions

Interpersonal therapy

IPT is a short-term psychotherapy focusing on the present and emphasizing the interpersonal context in which depressive symptoms occur (Klerman & Weissman, 1993). IPT originally was developed to treat Major Depressive Disorder in a general adult population, but has been adapted to treat women during the perinatal period (Spinelli et al, 2003). Seven studies have evaluated IPT’s efficacy in preventing PPD. Three of them incorporated IPT into the ROSE program (Reach Out, Stay strong, Essentials for new mothers), while a fourth assessed the efficacy of an adaptation of the ROSE program (REACH, Relaxation, Encouragement, Appreciation, Communication, Helpfulness) aimed specifically at racially and ethnically diverse pregnant adolescents. The ROSE program is a brief, manualized IPT-based group intervention designed by Zlotnick and colleagues (Zlotnick et al., 2001, 2006) to help pregnant women on public assistance improve close relationships, build social support networks, and manage the role transition to motherhood. The intervention comprises 4 weekly 60-minute group sessions during pregnancy. Session topics included identifying and managing role transitions, setting goals, developing social supports, and identifying and resolving interpersonal conflict. In a 2001 pilot study of the ROSE program, Zlotnick and colleagues studied 37 US pregnant women (35 study completers) who reported at least one risk factor for postpartum depression on a survey (e.g., previous episode of depression or PPD, mild to moderate levels of depressive symptoms, poor social support, or a life stressor within the last six months). All subjects were enrolled in standard antenatal care, and half of the subjects were randomized to receive the 4-session group intervention. Within 3 months postpartum, six (33%) of the control group had developed PPD (as measured by the major depression module of the SCID for DSM IV) versus none of the intervention subjects. Further, the change in BDI scores (administered before and after the intervention) for subjects in the intervention group showed a reduction in score and a significantly greater change when compared to the scores of the women in the control group (p<.001).

In 2006, the same group performed an expanded study of 99 women at 23 to 32 weeks’ gestation who were on public assistance and assessed as at-risk for PPD based on a score of >= 27 on Cooper’s 17-item PIPD. Subjects were randomly assigned to receive either standard antenatal care alone or standard antenatal care plus the ROSE program intervention (as described above), with an individual booster session after delivery. The 50-minute booster session reinforced skills introduced in earlier sessions and also addressed any mood changes related to interpersonal difficulties that had arisen since the birth of the baby. Depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline and again at three months post-delivery using the BDI. In addition, the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation, an interviewer-based assessment, was used to determine whether participants developed PPD. At three months postpartum, two (4%) of the women in the intervention condition, versus eight (20%) in the standard antenatal care condition, had developed PPD (p=0.04).

The third ROSE intervention was conducted by Crockett et al. (2008), who studied 36 rural African American women on public assistance between 24-31 weeks’ gestation who scored >= 27 on the PIPD. Women were randomized to the ROSE program or treatment as usual. Subjects in the intervention group received four 90-minute weekly group sessions and a 50-minute individual booster session 2 weeks after delivery. There were no significant between-group differences in EPDS scores at 2 weeks and 3 months postpartum.

The ROSE program was adapted by Phipps and colleagues, who published a 2011 US pilot study of 106 primiparous pregnant adolescents (≤17 years old when they conceived their pregnancy and <25 weeks gestational age at their first prenatal visit). Participants were screened for depression in pregnancy and were randomly assigned to receive either the REACH (Relaxation, Encouragement, Appreciation, Communication, Helpfulness) program, a highly structured adaptation of the ROSE program targeted toward pregnant adolescents, or to an attention and dose-matched control program. The REACH program consists of 5 one-hour prenatal sessions as well as a postpartum booster session. Sessions, which included video, role-playing, and homework components, focused on improving relationships via enhanced communication skills, developing social supports, managing stress, setting goals, and providing psychoeducation regarding PPD, expectations about motherhood, and psychosocial resources for new mothers. All subjects were given the book Baby Basics: Your Month by Month Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy, and the control condition involved using the book as a guide for a more general didactic program concerning maternal health, fetal development, nutrition, preparation for labor, and preparation for taking a new baby home.

Of note, while the initial study design involved group sessions for both control and intervention conditions, qualitative assessment from participants led the researchers to conclude that participants preferred individual sessions; accommodations were thus made to deliver sessions individually in both conditions. All participants were assessed for PPD (defined as an episode of MDD that occurred within the first 6 months after delivery) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Childhood version (KID-SCID) twice during pregnancy, once before randomization and once after intervention, and 3 times postpartum: within 48 hours of delivery and again at 6-week, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up visits. Intent-to-treat analyses showed no significant differences in incidence of PPD between intervention and control participants, though the authors note that the study was underpowered due to small sample size.

Three studies used IPT outside of the ROSE program. Zlotnick et al. (pilot study, 2011; n=54) studied the effect of an IPT-based intervention aimed at reducing depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in low-income pregnant women reporting intimate partner violence (IPV) within the previous year. Potential subjects were screened using the SCID for current affective disorders, PTSD, and substance use, and those screening positive were excluded from the study. Subjects were randomly assigned to receive either standard care, which included a listing of resources for IPV, or an intervention consisting of 4 individual 60-minute sessions over a 4-week period, followed by a 60-minute postpartum individual booster session within 2 weeks of delivery. This intervention combined components similar to those in the ROSE program—such as helping participants improve close relationships, build social support networks, and manage the role transition to motherhood—with components based on empowerment and stabilization models, which are models of treatment for women with IPV.

The EPDS was administered at intake, 5 to 6 weeks post-intake, 2 weeks post-delivery, and 3 months postpartum, while a measure of the incidence of MDD (Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Examination, LIFE) was administered at 3 months postpartum. Intent-to-treat analyses showed that there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of cases of MDD as measured by the LIFE interview; depressive symptoms as measured by the EPDS were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group at 5 to 6 weeks post-intake (during pregnancy; p=0.05), but no differences were found at 2 weeks or 3 months postpartum.

Grote and colleagues (2009; n=53) randomly assigned socioeconomically disadvantaged, non treatment-seeking women in the US scoring > 12 on the EPDS to receive either enhanced usual care or a manualized intervention called enhanced brief interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-B). Women in the enhanced usual care group received depression education materials and a referral to the behavioral health center in the same OB-GYN clinic, and their social workers were notified of their elevated depressive symptoms. Enhanced IPT-B consists of an engagement session, eight acute IPT-B sessions before birth, and biweekly or monthly maintenance IPT for up to six months after delivery. The engagement session was designed to assess each subject’s barriers to care and then address these using collaborative problem-solving. Subsequent sessions were aimed at helping subjects with interpersonal difficulties including role transition, role dispute, and grief. Intent-to-treat analysis showed that both before birth (3 months after baseline) and six months postpartum women in the intervention group experienced significant reductions in depression diagnoses (as determined by the SCID; p<.003, p<.005, respectively) and depressive symptoms (as measured by a 50% improvement on the EPDS; p<.001, p<.001, respectively).

Finally, Gao and colleagues, who studied 194 women in the general population in China (2010), randomized subjects to either a control group that received only “routine antenatal education,” consisting of two 90-minute sessions conducted by midwives, or an intervention group that received both the routine antenatal sessions and an IPT-based childbirth psychoeducation program. The intervention consisted of two 2-hour group sessions during pregnancy and one telephone follow-up session within two weeks of delivery. Intervention sessions, which were held following routine childbirth education classes to encourage attendance, focused on topics including managing role transition, identifying and establishing support systems, and improving communication. The follow-up phone session reinforced skills learned in previous sessions. Results showed a reduction at six weeks in mean EPDS scores from pre- to post-intervention for the intervention group, while mean EPDS scores for the control group increased from pre- to post-intervention. The changes in EPDS scores from pre- to post-test were significantly different between groups (p=.000).

In summary, of the seven RCTs evaluating IPT for prevention of PPD, four (including two pilot studies) demonstrated a reduction in the likelihood of developing depression postpartum. The majority of these trials were based on selecting women at risk for PPD, and, importantly, given IPT’s conceptual model, targeted the interpersonal conflicts that make up the psychological risk factors for PPD. Thus, the IPT orientation may be exceptionally well suited to PPD prevention. Finally, some of the successful approaches used non-clinical staff, suggesting that these interventions could have widespread application.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

CBT is a short-term psychotherapy combining components from cognitive therapy and behavior therapy; the former is aimed at identifying and challenging distorted thinking, while the latter focuses on learning techniques and skills to modify negative patterns of behavior. Findings on CBT have been more variable than those on IPT, with six studies (four of which targeted at-risk women only) reporting success and six with negative findings.

The first study reporting positive results was conducted by Chabrol et al. (2002), who randomized 241 French women determined to be at risk by EPDS score >9 to an intervention group or a control group. Mothers in the intervention received a one-hour individual prevention session two to five days postpartum, while still in the hospital. These sessions included an educational component (giving information about parenthood and guidance regarding infant development), a supportive component (featuring empathic listening, acknowledgement of maternal ambivalence and negative feelings, and normalizing mothers’ experiences), and a CBT component (aimed at challenging expectations of being a “perfect mother” and promoting problem-solving). All participants were given a second EPDS and instructed to complete the questionnaire and return it to the researchers four to six weeks postpartum. At four to six weeks, some women in each group had a significant reduction in the frequency of depression as defined by an EPDS score of ≥ 11; the proportion experiencing a reduction in the intervention group (48.2%) was greater than the proportion in the control group (30.2%, p=.0067). In addition, the mean EPDS score was significantly lower in the prevention group than the control group (p<.0024). An intention to treat analysis, which included all subjects with an EPDS score ≥ 9 immediately postpartum as well as subjects who refused further assessment and did not return the second EPDS, was also conducted; a repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant group × assessment interaction in favor of prevention (p<.01). Of note, the commonly used clinical cutoff for PPD on the EPDS is 13.

In a small 2008 pilot study in Korea, Cho et al. randomly assigned 27 at-risk pregnant women to either a control or an intervention group. Risk was determined by a BDI score >16. Those in the intervention group met with a clinical psychologist during pregnancy for nine one-hour individual CBT sessions every two weeks. These sessions focused on psychoeducation about depression; identifying and modifying irrational or negative thoughts, particularly those related to the marital relationship; and communication and behavioral skills training. Women in the control group received one psychoeducational session about depression and strategies for minimizing depressive symptoms. Women who received the CBT intervention had a significantly lower rate of PPD assessed at 1 month postpartum than women in the control group, as measured by the BDI (p<.01). The researchers hypothesize that the intervention’s efficacy was a result of the individual sessions and treatment compliance with the multiple session approach.

Milgrom et al. (2010) studied 143 Australian women determined to be at risk by EPDS and/or Risk Assessment Checklist score ≥ 13. Women, who were recruited at 20 to 32 weeks gestation, were randomly assigned to usual care or to receive a CBT-based self-help workbook as well as eight weekly individual telephone support sessions. The workbook included sections on nurturing the mother- and father-baby relationship, managing relationship and life changes, and behavioral and cognitive strategies for coping with anxiety and depression. Participants in the intervention group were instructed to read a portion of the workbook each week and then discuss the content with a therapist over the phone. The first seven sessions occurred during late pregnancy, while the eighth session occurred six weeks after birth. Results indicated that participants in the intervention group reported significantly lower levels of depression on the BDI-II than the control subjects at 12 weeks postpartum (p<.01).

Tandon et al. (2011) studied 61 low-income at-risk US women (as determined by CES-D score ≥ 16 and/or a lifetime depressive episode) enrolled in a home visiting program. Of note, this study included both pregnant women and women who had a child fewer than six months old, which raises the possibility that for women in the latter category, the intervention was actually treating rather than preventing PPD. Participants were randomized to an intervention group, who received a six-session weekly CBT-based group intervention in addition to home visits, and a control group, who received routine home visits plus information regarding perinatal depression (but not the CBT-based program). The group intervention was a modified version of Munoz et al.’s Mothers and Babies (MB) course, a CBT-based program aimed at preventing perinatal depression by teaching participants to manage mood. Group sessions were supplemented by one-on-one reinforcement of key group material by home visitors between group sessions (in contrast to women in the control group, who also received one-on-one home visits but without the added CBT reinforcement component). Results indicated that at 3 months post-intervention, 33% of women in the control group reported levels of depressive symptoms that met clinical cutoff for depression on the MMS (Maternal Mood Screener, Le & Munoz, 1998), versus 9% of women in the intervention group, a statistically significant difference (p<.05).

Two studies conducted in 2012, one by Mao et al. in China and the other by Kozinszky et al. in Hungary, both showed positive outcomes for CBT using group interventions with participants not at risk for PPD. Mao et al.’s study, which looked at 240 primiparous women starting in their 32nd week of pregnancy, randomized participants to either standard antenatal education, which consisted of four 90-minute childbirth education sessions conducted by obstetrics nurses, or the ESMGT (Emotional Self-Management Group Training) program, which comprised four weekly group sessions and one individual counseling session. Participants attended the intervention sessions as a couple. Themes of the group sessions included understanding emotional and interpersonal implications of Chinese cultural norms around delivery (e.g., negative reaction to birth of female baby), problem solving and positive communication, relaxation exercises and cognitive restructuring, and enhancing self-confidence. Scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire - 9 (PHQ-9) administered at completion of the intervention (36 weeks) were significantly lower for women in the intervention group than for those in the control group (p<.01). Moreover, mean EPDS scores at 6 weeks postnatal were also significantly lower for the intervention group than the control group (p<.05). Using the SCID at 6 weeks postpartum to assess for PPD among participants who scored > 11 on the EPDS revealed a significantly lower incidence of PPD (2.7%) in the intervention group versus the control group (9.3%; p<.05).

Participants in Kozinszky et al.’s study (n=1719) were randomly assigned to either a control group, which attended 4 group meetings consisting of routine education on pregnancy, childbirth, and baby care (which is more or less identical to treatment as usual) or an experimental group, which received four 3-hour group psychotherapeutic/psychoeducational sessions; these latter sessions incorporated elements of psychoeducation, CBT, IPT, and group therapy. Fathers were permitted to attend sessions. At 6 weeks postpartum, PPD prevalence, as determined by a cut-off score of 11/12 on the Leverton Questionnaire (LQ), was significantly lower among intervention participants than control participants (p<.01). Moreover, depressive symptoms assessed with the LQ at 6 to 8 weeks after delivery were significantly lower in the intervention group versus the control group (p<0.001).

While the six studies highlighted above all found positive effects for a CBT intervention, six additional studies found the opposite. In a US pilot study of low-income mothers of preterm infants (≤33 weeks gestation; Silverstein et al. 2011, n=50), participants, who were not screened for antenatal depression, were randomized to receive either Problem-Solving Education (PSE), a one-on-one CBT-based problem-solving intervention, or usual hospital services, which included access to a social worker through the time the infant was discharged. Subjects in the intervention group received 4 individual sessions ranging from 25 to 60 minutes, beginning while infants were still in the hospital and continuing weekly or biweekly. Sessions were conducted in a location of the subject’s choosing (usually hospital or home). In each session, educators helped subjects identify a problem, set goals, choose a solution, and make an action plan. There were no significant group differences in the rates of moderately severe depression symptoms (as defined by a score of ≥11 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS)) occurring in the intervention versus control groups, though there was a trend for the intervention subjects toward a lower chance of experiencing an episode of such symptoms.

Hagan et al. (2004, in Australia) studied 199 mothers of very preterm (<33 weeks) or very low birth weight (<1500g) infants. Participants were evaluated two weeks postpartum using the SADS (Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia); those who were judged not depressed were then randomized to a control group, who received standard care for mothers of preterm infants (including social work contact, regular biweekly parent education groups, and a developmental physiotherapy playgroup during the first postpartum year), and an intervention group, who received standard care plus a brief individual debriefing session regarding their experience during pregnancy and then six weekly 2-hour sessions of group CBT between 2 and six weeks postpartum. CBT session content included adjusting to parenthood with a preterm infant, information about PPD, identifying and modifying negative thinking patterns, and short- and long-term goal setting. All participants were given the SADS at two, six, and 12 months; results revealed no significant differences in the incidence of depression between intervention and control groups at any time point.

Austin et al. (2008) studied 277 Australian women who had an EPDS score > 10 and/or a score of > 23 on the Antenatal Risk Questionnaire, or a reported prior history of depression. They were randomized to a control group, which received an information booklet in addition to standard care, and an intervention group, which received a CBT group intervention in addition to the information booklet and standard care. The intervention, which consisted of six weekly 2-hour group sessions plus a later follow-up session, focused largely on behavioral strategies, such as goal setting, problem solving, and relaxation training, to prevent and manage low mood, anxiety, and stress in the postpartum period. Participants completed the EPDS at the initial interview (Time 1), after the final session of the CBT program (Time 2), two months postpartum (Time 3), and four months postpartum (Time 4), as well as the depression and anxiety subsections of the MINI (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) at Times 1, 3, and 4. Intent to treat analyses showed no significant group differences in EPDS scores at Times 2, 3, and 4, and no reduction in the incidence of depression as measured by the MINI.

Finally, three additional studies used the same intervention as Tandon et al. (in a successful study cited above), but showed no effect. Munoz et al., whose work in 1995 in depression in a primary care setting was the initial basis for the intervention, conducted a pilot study in 2007 in 41 high-risk Latina women in the US determined to be at risk by a past history of MDE and/or a CES-D score ≥ 16. Participants were randomized to either a control group or an intervention group, which received the Mothers and Babies (MB) course, a 12-week CBT group intervention followed by 4 individual booster sessions at one, three, six, and 12 months. After one year, 14% of the women in the intervention group vs. 25% of the women in the control group developed a new onset of major depression, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

In a multisite study, Zayas et al. (2004) studied 187 African-American and Latina women in the US determined to be at risk for PPD by a BDI score ≥ 14 in their third trimester. They were randomized to a control group receiving treatment as usual from their health center and an intervention group who received a 3-part intervention consisting of eight group sessions of CBT, 4 psychoeducation sessions on infant development and maternal sensitivity, and social support building from the therapist. Results showed no significant group differences in BDI scores at 2 weeks and 3 months postpartum.

Similarly, Le et al. in 2011 studied 217 low-income US Latina women determined to be at high risk by CES-D score ≥ 16 and/or self-reported personal or family history of depression. Participants were randomized to receive usual care or a CBT group intervention modified from Munoz’s MB course and consisting of eight weekly 2-hour sessions focusing on developing mood regulation skills to prevent perinatal depression, followed by three postpartum individual booster sessions conducted at six weeks, four months, and 12 months. Participants were evaluated at 5 time points, twice during pregnancy—pre-intervention (T1) and post-intervention (T2)—and three times after birth, at six weeks (T3), four months (T4), and 12 months postpartum (T5). Results showed that the intervention had a significant short-term effect on depressive symptoms (from T1 to T2 — that is, from early to late pregnancy (as measured by the BDI; p=.03)) — but that these results did not persist into the postpartum period. There were no significant differences in the rates of major depressive episodes (as measured by the Mood Screener, Munoz, 1998) at any of the time periods or cumulatively. Le et al. attribute this lack of significant group differences in part to the low depressive symptoms and relatively low incidence of major depressive episodes among women in both the intervention and control groups. They offer multiple possible explanations for this low incidence, including attrition (30% of subjects were lost to follow-up) and low session attendance (roughly half of the intervention participants did not attend all four classes, and 12% did not attend any).

The interventions evaluated in the six successful studies varied widely in terms of sample characteristics, duration and intensity of the intervention, modality of delivery (i.e., individual versus group), and level of training of the interveners. Of note, three of the four studies using individual CBT (Milgrom et al., Cho et al., and Chabrol et al.) were successful, while five of the eight group-based interventions (Le et al., Austin et al., Munoz et al., Zayas et al., and Hagan et al.) were not. Two of the three studies that used a group-based approach with individual booster sessions administered after the completion of the group sessions (Munoz and Le) were not successful. However, Tandon’s study was successful using group sessions plus individual sessions between group sessions. It is also notable that two of the unsuccessful studies enrolled mothers of early preterm babies only, which may have affected participants’ risk of developing PPD.

Postnatal Psychological Debriefing

Psychological debriefing is a controversial treatment typically consisting of a single semi-structured psychological interview during which the interviewer explores a person’s experience of a traumatic event with the aim of reducing psychological distress after trauma and preventing PTSD. These interviews are usually administered within a month of a potentially traumatic event (Rose et al., 2002). A 2002 Cochrane review of 11 studies comparing subjects who received psychological debriefing with no-intervention controls concluded that psychological debriefing was not successful in preventing PTSD; two trials found that it actually made subjects symptomatically worse (Rose et al., 2002).

In the postnatal setting, debriefing most often takes the form of a discussion of labor and delivery experiences with an empathic listener in a structured format soon after delivery (Small et al., 2000). Five RCTs have examined the effect of postnatal psychological debriefing on the prevention of PPD. Two studies showed positive effects and three showed no difference. Lavender and Walkinshaw (1998) studied 120 British women in the general population with normal spontaneous at-term vaginal deliveries. Subjects, who were not screened for antenatal depression, were randomized to receive treatment as usual or a single debriefing session prior to discharge with a midwife not formally trained in counseling. The session consisted of “an interactive interview in which they spent as much time as necessary discussing their labor, asking questions, and exploring their feelings.” All participants were mailed a HADS questionnaire three weeks after discharge and asked to return it. Scores on the HADS range from 0 to 21. Results showed that women who received the intervention were significantly less likely to have high depression (defined as a depression score > 10 points; p<.0001), as well as high anxiety (defined as an anxiety score > 10 points; p<.001) three weeks post-delivery. Of note, the HADS has not been validated for postnatal care, though it has been validated in many health services fields. The researchers explain that they used the HADS rather than the EPDS because it allows for subgroup analysis, which defines both anxiety and depression.

In 2005, Gamble and colleagues studied 103 Australian women who had experienced a distressing or traumatic birth, as defined by Criterion A of DSM-IV for PTSD: women were asked within 72 hours of birth if during labor or birth they had feared for their or their baby’s life, or feared serious injury or permanent damage. Women who responded positively to these questions, and thus met criterion A of DSM-IV, were randomized to a single debriefing session within 72 hours after birth, as well as a telephone follow-up at four to six weeks, or to treatment as usual. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with respect to rate of obstetric intervention in the current pregnancy. At three months postpartum, women in the intervention group were significantly less likely to develop PPD (as determined by an EPDS score > 12) than women in the control group (p=.002). While there was no difference at four to six weeks or three months postpartum between groups in numbers of women meeting criteria for PTSD, the total PTSD symptoms scores at three months (but not at four to six weeks) were significantly higher in the control group than in the intervention group (p=.035), suggesting that the intervention was effective in reducing symptoms over the longer term.

The remaining three studies of postnatal debriefing did not have significant results. Small and colleagues (2000, 2006) conducted an RCT with 1041 Australian women not screened for antenatal depression who had operative births (defined by the study authors as birth by Caesarean section, forceps, or vacuum extraction). Women were randomized to a debriefing session prior to discharge or to a control group who received a pamphlet about resources for postpartum mothers (intervention subjects were given the pamphlet as well). There were no significant group differences in rates of depression (as defined by EPDS score ≥ 13) at either six months (Small et al., 2000) or four to six years postpartum (Small et al., 2006).

Similarly, Tam et al. (2003) studied 516 women in Hong Kong recruited within 48 hours after delivery who experienced “suboptimal outcomes” during pregnancy and delivery (e.g., antenatal complications resulting in hospital admission, such as gestational diabetes or placenta previa; elective and emergency Caesarean sections; or instrumental vaginal delivery). Women were randomized to an intervention group, which received educational counseling, or to a control group, which received treatment as usual. The intervention consisted of two parts, an educational component and a counseling component; the former, based on the premise that lack of information contributed to psychological symptoms, consisted of explanation and clarification of the events surrounding the birth, while the latter entailed encouraging participants to discuss their emotional reactions to the unexpected events. Number and duration of sessions were decided by the research nurse on a case-by-case basis; the number of sessions ranged from one to four, and total duration over all sessions ranged from 25 to 50 minutes, with a median total time of 35 minutes. Results of the HADS and Global Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (Goldberg and Williams, 2000) administered before intervention, at six weeks post-delivery during a postnatal follow-up visit, and at six months (via mail) showed no significant group differences in terms of depressive symptoms (as measured by the HADS) or rates of possible cases of PPD (using 4/5 cutoff on the GHQ), although among women who underwent elective Cesarean sections, those in the intervention group had significantly lower depression scores than those in the control group (p=.009).

Also in 2003, Priest et al. studied 1730 Australian women in the general population recruited 24 to 72 hours after delivery. Participants were randomized either to a control condition, consisting of standard postnatal care, or to an intervention, consisting of a single standardized debriefing session in their hospital rooms. The sessions ranged from 15 minutes to one hour and were conducted by research midwives with training in critical incident stress debriefing. EPDS questionnaires were mailed at two, six, and 12 months postpartum, and participants with EPDS scores > 12 at any time point were given the SADS within two weeks of the questionnaire by research clinical psychologists to further assess symptomatology and diagnosis. Results indicated no significant differences between groups in EPDS scores at two, six, or 12 months or in proportions of participants meeting diagnostic criteria for major or minor depression.

In summary, the debriefing trials include two studies with positive effects and three showing no difference. However, the factors associated with success varied tremendously, e.g., women at risk for psychiatric or medical reasons or without any predisposing factors, length of intervention. More research on using debriefing as a preventive intervention for PPD must to conducted to determine the potential for this clinical strategy.

Across psychological interventions as a whole, 12 trials showed positive effects (four IPT, six CBT, and three debriefing), with an additional 2 IPT pilot studies showing a trend toward a positive result that did not reach statistical significance. One IPT study, six CBT studies, and three debriefing studies did not show a difference. Factors that contribute to these differences will be discussed at greater length in the conclusion.

Psychosocial Interventions

Antenatal and Postnatal Classes

To date, six RCTs have been conducted to evaluate group-based psychoeducational interventions to prevent PPD; two RCTs have looked at individual psychoeducational approaches to preventing PPD. The approaches assessed in the group-based studies varied in terms of the content of the sessions as well as the number and timing of sessions, group size, and type of facilitator. Common topics included a general introduction to PPD and how to identify and treat it, discussion of the social and emotional challenges of pregnancy, and education about self-care, social support, and problem-solving skills. In addition, several of the interventions addressed unrealistic beliefs about pregnancy and motherhood.

Three of the six group-based studies showed a difference between intervention and control groups. In the UK in 2000, Elliot and colleagues studied 99 women at risk for clinical depression (as determined by a reported history of depression and/or CESD score ≥ 16). Women were randomized to 11 group sessions (five during pregnancy and six postpartum); the control group received standard pre- and postnatal care. There was a significant decrease in depressive symptoms and rates of clinical depression in at-risk primiparous, but not at-risk multiparous, women (p<.005).

In Australia, Matthey et al. (2004) randomized 268 women in the general population to three conditions: usual service (“control”), experimental (“empathy”), or non-specific control (“baby-play”). The latter condition controlled for the nonspecific effects of the intervention, which were the provision of an extra class, asking couples to think about the early postpartum weeks, and receiving two booster sessions. All subjects received six routine antenatal classes. Those in the experimental group were randomized to receive an additional class in week five focused on postpartum psychosocial issues. In the non-specific control condition, the extra class focused on the importance of play for infants. Participants in the usual service condition received the six antenatal classes only. Results showed a significant interaction between condition and self-esteem on maternal mood at six weeks, but not six months: women with low self-esteem who had received the intervention scored significantly lower on the EPDS at six weeks, but not at six months, than women with low self-esteem in either of the two control conditions (p<.01). This study differed from the others reviewed in this article in its inclusion of partners in all sessions (both control and experimental).

Lara and colleagues (2010, n=136) also found significant reductions in clinical depression incidence and symptomatology in their treatment group, this time in Mexico. Lara et al. examined at-risk pregnant women (as determined by CESD score ≥ 16 and/or a self-reported history of depression). Participants were randomized to either a usual care or an intervention group. All participants received a self-help book about depression, which included a directory of community mental health services. The intervention groups, which met weekly for eight two-hour sessions, were composed of five to ten participants each. Session topics included information about pregnancy and the postpartum period as well as strategies to reduce depression through improving self-care and self-esteem, increasing social support, engaging in positive thinking, and addressing issues related to past grief and loss as well as unrealistic expectations regarding pregnancy and motherhood. Childcare was offered during the classes. Two individual booster sessions were provided by trained research assistants at six weeks and four to six months postpartum. The researchers found that the cumulative incidence of major depression over the course of the study, as measured by the SCID, was significantly lower in the intervention groups than in the control group (p<.05). In contrast, there were no significant group differences in reduction of depressive symptoms (as measured by the BDI-II). Of note, there was a substantial difference in attrition before the start of the intervention, with substantially higher attrition in the intervention group than the control group; 57.6% of randomized intervention participants never attended the intervention, versus 7.8% of control participants who were lost in this same period. Because of this disparity, findings of this study should be interpreted with caution.

The remaining three group-based studies of at-risk women failed to demonstrate prevention of PPD symptoms. Stamp et al. (1995, n=144, Australia) offered women in the intervention group two sessions during pregnancy and one postpartum, led by a midwife educator; sessions focused on planning for and managing life changes around having a baby. The control group received care as usual. In Buist et al.’s study (1999, n=45, Australia), subjects were randomized to a control group who received care as usual or an intervention group who received 10 sessions (authors did not indicate which sessions were given during pregnancy and which were offered postpartum), which focused on parenting and coping strategies. Brugha et al. (2000, n=209, in the UK) offered to women in the experimental group a six-session antenatal intervention, led by nurses and occupational therapists with no formal training in psychological interventions. The control group received care as usual. The intervention focused on cognitive and problem-solving approaches as well as enhancing social support. Participants in the intervention group also met for a reunion class at eight weeks postpartum. Importantly, these three trials had serious methodological limitations. All three studies were conducted with women identified as at-risk based on screening questionnaires designed by the researchers (versus validated approaches). The studies had low group attendance (Stamp et al.; Brugha et al.), high attrition (Stamp et al.; Brugha et al.), and small sample size (Buist et al). In addition, the interveners in Stamp et al.’s and Brugha et al.’s studies did not have any specific training, whereas, among the positive studies, Lara et al. describes their trained facilitators as having “extensive experience” and Elliot et al.’s groups were run by a health visitor and clinical psychologist.

Two RCTs, one conducted in Australia by Hayes et al. (2001; n=206) and the other in the US by Howell et al. (2012; n=540), assessed the preventive effects of individual psychoeducation sessions on postpartum depressive symptoms in women in the general population. In the multisite study by Hayes and colleagues, women in the intervention group received an information booklet about PPD, an audiotape of one woman’s experience with PPD, and a single individual session with a midwife with experience in antenatal education, who reviewed the materials with them. The control group received care as usual. No significant group differences were found on the POMS (Profile of Mood States) at eight to 12 weeks, nor at 16 to 24 weeks.

In Howell’s study, conducted with Black and Latina mothers, women in the intervention group received two sessions, the first while still in the hospital post-delivery and the second over the phone two weeks later. The control group received enhanced usual care, consisting of a list of community resources and a control telephone call at two weeks. In the first intervention session, the therapist reviewed with the mother written materials describing typical symptoms of the postpartum experience and suggesting ways to manage these; additionally, the mother was provided information about social support and community resources. In the second session, two weeks later, the therapist assessed the subject’s symptoms and her skills in managing these; action plans and to-do lists were also reviewed and created. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the EPDS at four time-points: before randomization and then three weeks, three months, and six months later. Positive screens (defined as EPDS score ≥ 10) were significantly less common at three weeks postpartum among women in the intervention group than among those in the usual care group (p=.03); values for three months and six months did not reach significance (p=.09 and p=.11, respectively).

Postnatal Support

Five RCTs have evaluated a variety of postnatal support interventions as a means of preventing PPD. None of these studies screened for antenatal depression. Of the five, two showed effectiveness in preventing PPD and three had negative results. In a 1999 Australian study showing effectiveness in preventing PPD, Armstrong et al. studied 181 women who reported at least one first-tier risk factor for “family dysfunction” on a questionnaire (e.g., physical forms of domestic violence, childhood abuse of either parent, single parenthood, and ambivalence toward pregnancy) and/or at least three second-tier risk factors (e.g., maternal age < 18, unstable housing, financial stress, less than 10 years of maternal education, low family income, social isolation, history of mental health disorder in either parent, alcohol or drug abuse, and domestic abuse other than physical violence). Subjects were recruited just after delivery and were randomly assigned to receive either standard community child health services care or structured home visits from trained child health nurses supported by a pediatrician and social worker. Of note, the intervention was designed to benefit (and assess) infant and family health outcomes in addition to maternal health outcomes. Home visits occurred weekly for the first six weeks, every two weeks until three months, and then monthly until six months postpartum. Mothers in the intervention group had significantly lower EPDS scores at six weeks (p<.05), and there was a significant difference between the percentage in each group with EPDS scores greater than the clinical threshold of 12 (p<.05), in favor of the intervention group.

In 2009, Dennis et al. screened at-risk women within the first two weeks postpartum using the EPDS, and randomized those scoring > 9 (n=612) to care as usual or to individualized telephone-based peer support from a volunteer who had previously recovered from PPD and attended a four-hour training session. The authors found that women in the intervention had significantly lower EPDS scores at 12 weeks (p<.001) than those in the control group. There were no group differences at 24 weeks, but the authors attribute this to the fact that participants who were identified as clinically depressed at 12 weeks were referred for treatment.

Three additional studies showed no effect of an intervention. In 2000, Morrell et al. studied 623 at-risk women in the UK (defined as those women who scored ≤ 24 on the Maternity Social Support Scale and/or those having a past history of mental illness, family psychiatric history, past PPD, or a mother who had PPD). Participants were randomized to usual postpartum care (which included care at home by community midwives) or to an intervention group who received lay support by trained support workers in addition to usual care. Support workers, who underwent eight weeks of training, provided both practical and emotional support (e.g., building mothers’ confidence in caring for their babies and reinforcing midwifery advice about feeding). Participants in the intervention group received up to 10 visits from the support workers, with each visit lasting between 10 and 375 minutes. The primary outcome measure was general health, as measured by the short form-36 (SF-36); depressive symptoms, as assessed by the EPDS (which were distributed and returned via mail), were a secondary outcome. There were no group differences in EPDS scores at either or 24 weeks postpartum.