Abstract

Approximately 60% of women who labor receive some form of neuraxial analgesia, but concerns have been raised regarding whether it negatively impacts the labor and delivery process. In this review, we attempt to clarify what has been established as truths, falsities, and uncertainties regarding the effects of this form of pain relief on labor progression, negative and/or positive. Additionally, although the term “epidural” has become synonymous with neuraxial analgesia, we discuss two other techniques, combined spinal-epidural and continuous spinal analgesia, that are gaining popularity, as well as their effects on labor progression.

Keywords: Labour, analgesia, neuraxial, epidural

Background

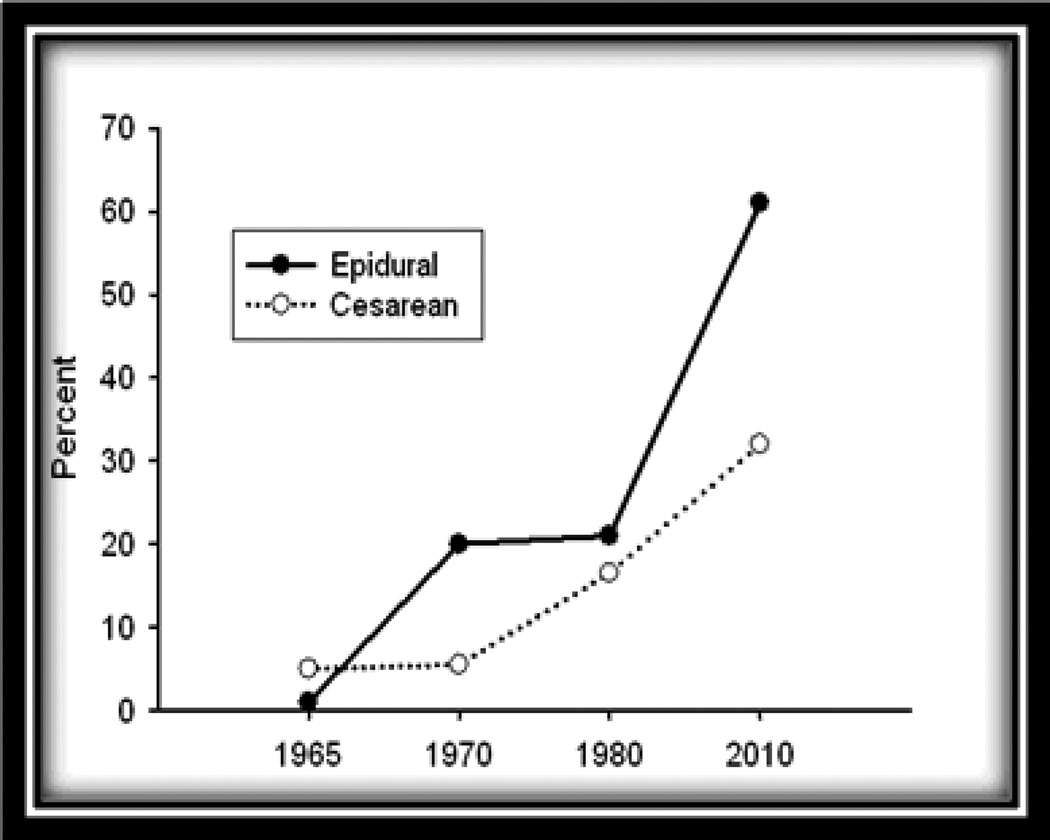

Although there is a recent decline in the number of births in the United States, the cesarean birth rate has risen steadily over the past 14 years, and as of 2010, has reached 32.8% of all women delivered in the United States. This represents a 60% increase since 19961. Epidural analgesia for labor and delivery was introduced in 1938, but began gaining popularity in the 1970’s2,3, such that approximately 61% of women delivered in the United States receive such analgesia4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rate of epidural analgesia use during childbirth in the United States with concomitant cesarean birth rates.

This concomitant increase has prompted some to question whether the rise in cesarean birth rates has been influenced by the increased use of epidural analgesia during childbirth. This concern is buttressed by the fact that the leading indication for primary cesarean is dystocia, diagnosed when labor is ineffective, and that epidural analgesia reportedly prolongs labor, specifically the second stage.

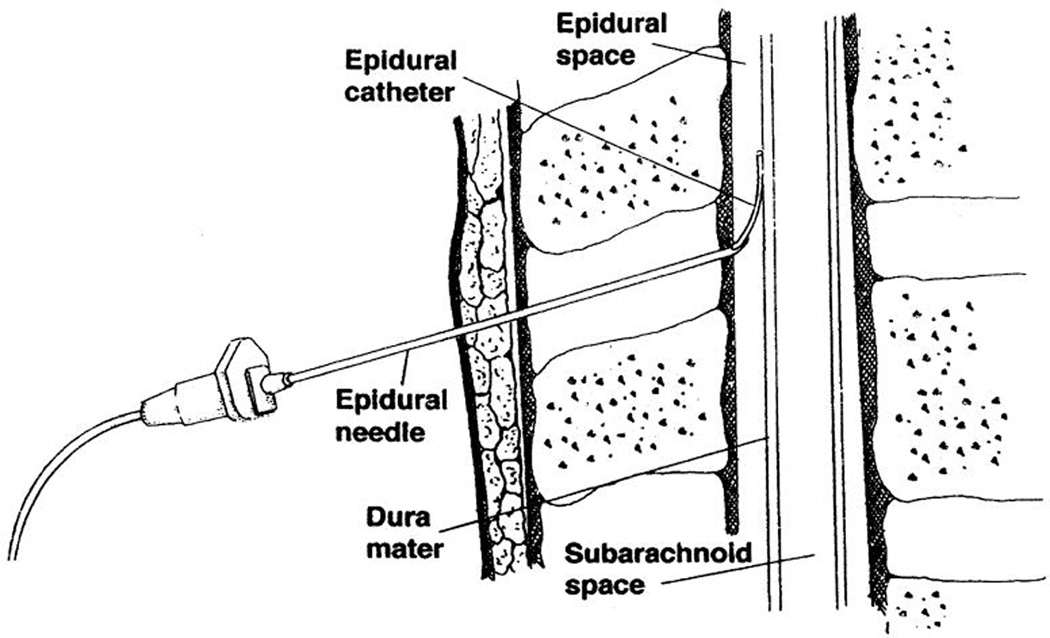

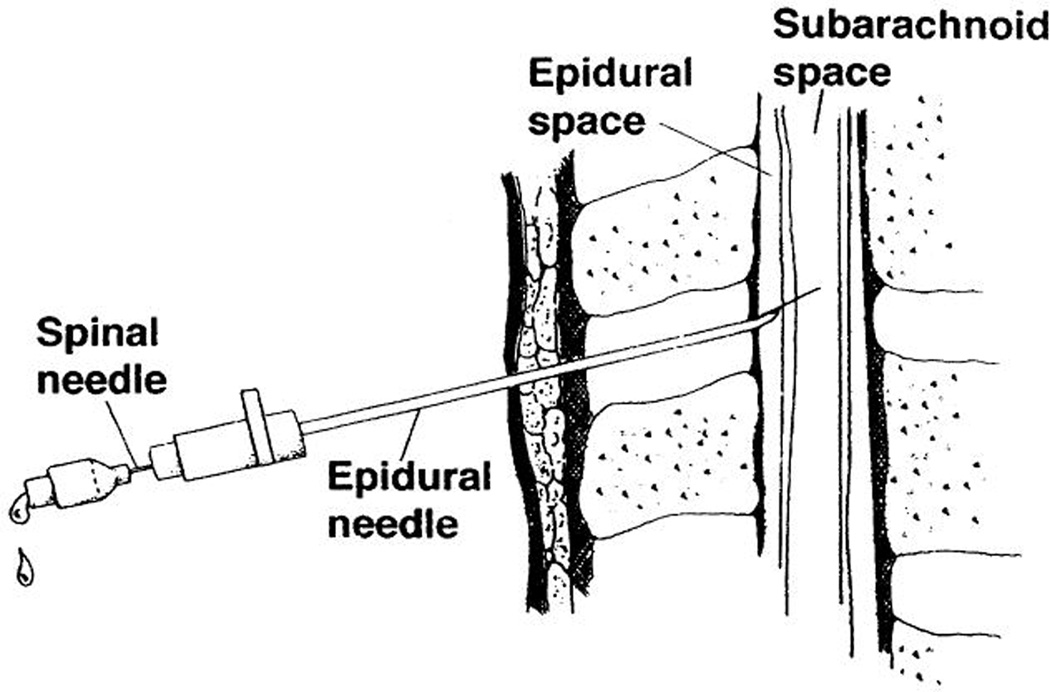

The most popular techniques for neuraxial analgesia during labor include continuous lumbar epidural (Figure 2) and combined spinal-epidural analgesia (Figure 3). A third less popular technique, continuous spinal analgesia, was withdrawn from the US market in the 1990’s due to technical problems leading to neurological sequelae. With the advent of new equipment and procedural changes, there is renewed interest.

Figure 2.

Catheter being threaded into the epidural space5.

Figure 3.

Spinal needle inserted through epidural needle to penetrate dura, confirm cerebrospinal fluid, and inject medications prior to threading catheter into epidural space5.

Although neuraxial analgesia in labor is undisputedly superior to other methods of pain relief such as intravenous opioids, there is concern that neuraxial analgesia lengthens labor and leads us to question, “Is it a friend or foe”?

Labor Progression

Traditionally, the duration of labor was subject to personal interpretation because there was no consensus as to when labor commenced6. Friedman first described the normal labor curve in 1954 and continued to extensively study labor over the next four decades. Subsequently, his sigmoid-shaped labor curve was widely accepted7–9.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has defined normal labor as “the presence of uterine contractions of sufficient intensity, frequency, and duration to bring about demonstrable effacement and dilation of the cervix”10. In contrast, abnormal labor remains difficult to define. Importantly, frequent interventions such as the use of epidural analgesia have been reported to alter normal labor, further complicating its meaning11. On the other hand dystocia, difficult labor, is characterized by abnormally slow labor progress and arises from four distinct abnormalities: 1) expulsive forces, 2) presentation, position, or fetal development, 3) maternal bony pelvis, and 4) soft tissues of the reproductive tract that form an obstacle in fetal descent. The abnormalities can be mechanistically simplified into three categories to include prolongation, protraction, and arrest disorders (Table 1)12.

Table 1.

Three labor disorders based upon Friedman labor curves

| Labor Pattern | Nulliparous | Multiparous |

|---|---|---|

| Prolongation Disorder | ||

| Prolonged latent phase | > 20 hours | > 14 hours |

| Protraction Disorders | ||

| Protracted active-phase dilation | < 1.2 cm/hour | < 1.5 cm/hour |

| Protracted descent | < 1 cm/hour | < 2 cm/hour |

| Arrest Disorders | ||

| Prolonged deceleration phase | > 3 hours | > 1 hour |

| Secondary arrest of dilation | > 2 hours | > 2 hours |

| Arrest of descent | > 1 hour | > 1 hour |

Recently, investigators forming The Consortium on Safe Labor studied 62,415 women and found that nulliparous women progress from 4 to 6 cm cervical dilation much slower than previously thought. Another finding showed that epidural analgesia was associated with slower labor11,13. Therefore, these authors proposed re-examining the definitions of normal and abnormal labor. One such suggestion would be allowing labor to continue longer than what is currently practiced, possibly resulting in a reduction in cesarean rates.

Pain and Dystocia

There are reports on the association between the intensity of labor pain and dystocia. Although these studies do not establish a cause and effect relationship, they strongly suggest that greater labor pain is associated with obstructed labor14,15. It is well documented that there is a correlation between endogenous plasma epinephrine and cortisol levels with labor progression16. Indeed, women in labor who request epidural analgesia have significantly higher cortisol levels than of women who do not. These levels decrease after relief of pain17. Similarly, epinephrine levels decrease after initiation of epidural analgesia18. This decrease in alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation may enhance uterine perfusion leading to a more effectual contraction pattern19,20. This is likely due to greater sensitivity of the uteroplacental vascular bed to catecholamines in comparison to systemic vasculature21. This is further evidenced by epidural analgesia reducing maternal epinephrine levels by eliminating psychological and physical stress associated with painful uterine contractions or by denervating the adrenal medulla18.

In this review, we will address the impact of neuraxial analgesia on the progress of labor by subdividing the topics to include generally accepted facts, falsities, areas where uncertainty exist, and the future direction of epidural, combined spinal-epidural, and continuous spinal analgesia.

Facts

Epidural analgesia is associated with prolonged labor

The effect of epidural analgesia on the progress of labor has been extensively studied. For example, Anim-Souman and colleagues19 performed a Cochrane review of epidural analgesia effects in labor using 38 trials involving 9658 parturients. Although there were no significant differences in the length of the first stage of labor, second stage was lengthened by an average 15 minutes. Of course, the clinical significance of such a limited prolongation is debatable.

Epidural analgesia is associated with an increased risk of instrumental delivery

In the same Cochrane review, 23 randomized trials (N=7935) were analyzed comparing operative (forceps or vacuum-assist) deliveries in relation to epidural analgesia. Operative vaginal delivery was linked to epidural analgesia (RR 1.42; 95%CI 1.28–1.57)19. Several theories of possible etiologies include local anesthetic agents and narcotics interference with normal expulsive efforts via suppression of the bear-down reflex20 and failure of appropriate time to allow internal rotation of the fetal head21.

Combined spinal-epidural is associated with an increased risk of instrumental delivery

There are four studies that included 925 women that showed no statistical difference in risk of instrumental delivery between combined spinal-epidural and epidural analgesia22.

Fallacies

Early epidural placement slows labor progression and increases risk of cesarean delivery

Based upon prior studies23,24, epidural analgesia initiation before 4 cm cervical dilation was associated with slower labor progression. Several groups of investigators have concluded that this is indeed not the case25–29. These studies included women who either demonstrated cervical change indicating spontaneous labor, were at least 3 cm dilated, or made no mention of minimum cervical dilation. Wong30 and Wang31 on the other hand, demonstrated in 2 large randomized control trials that even prior to 2 cm cervical dilation, neuraxial placement had no effect on labor progression. Furthermore, these investigators observed no effects of early labor analgesia on operative vaginal or cesarean birth rates. More recently, a systematic review of 6 studies (N=15,399) showed no increased risk of cesarean (pooled risk ratio 1.02 95% CI 0.96–1.08) or instrumental (pooled risk ratio 0.96 95% CI 0.89–1.05) delivery for women receiving early epidural (defined as 3 cm or less) in comparison with late epidural placement32.

The aforementioned findings have led ACOG to conclude that, “There is no other circumstance where it is considered acceptable for an individual to experience untreated severe pain, amenable to safe intervention, while under a physician's care. In the absence of a medical contraindication, maternal request is a sufficient medical indication for pain relief during labor. Pain management should be provided whenever medically indicated.”33

Ambulatory epidural analgesia hastens labor

Maternal ambulation has been reported to enhance pelvic diameters, increase coordination of uterine contraction intensity and frequency, and shorten stage I labor24,34. The “walking epidural”, typically described as a low-concentration local analgesic35 or opioid-only technique that minimizes motor blockade of the lower extremities, was thought to hold promise for hastening labor by allowing for ambulation. In the three randomized control studies35–37, there was no effect on labor progression benefit with maternal ambulation during neuraxial analgesia. These studies also concluded that maternal ambulation had no effect on analgesia requirement or mode of delivery.

Neuraxial analgesia increases the risk of cesarean delivery

The authors of the previously described Cochrane Review analyzed 27 trials on the effects of epidural analgesia on cesarean rates and found no effect on the overall risk of cesarean delivery19. Similarly, combined spinal-epidural was not found to increase cesarean delivery rates22.

Uncertainties

Epidural analgesia interferes with the propagation of muscular activity within the uterus

Some investigators have theorized that epidural analgesia lengthens labor by provoking dysfunctional propagation of electrical activity within the uterine muscle. Per this theory, there is inhibition of the fundal origin of uterine contractions with disruption of the transmission of contractions to the lower uterine segment38. Other investigators have directly analyzed uterine activity with and without epidural analgesia and found that such analgesia did not influence uterine activity in the first stage of labor. However, there was a lower level of uterine contraction, frequency, and intensity in the second stage39. It was hypothesized that the observed decrease in uterine activity during the second stage may contribute to the increased operative vaginal delivery rate40.

Neuraxial analgesia cause fetal malposition31

Lateral and posterior positions of the fetal head may be associated with more painful, prolonged or obstructed labor and difficult delivery41. One suggestion is that epidural analgesia may be associated with failure of spontaneous rotation to an occiput anterior position12. Fetal position was an outcome in four trials of neuraxial analgesia during labor and results of these trials have not resolved the controversy whether or not neuraxial analgesia affects fetal position19. Of interest, it is postulated that early initiation of epidural analgesia increases the risk of malposition versus latter labor secondary to optimal positioning of the fetal head at this stage23.

Routine use of epidural analgesia during labor

A recent study by Wassen et al42 assessed the effects of routine epidural analgesia during labor versus initiation upon maternal request. Although the authors suggest that routine epidural analgesia may increase the rate of operative deliveries, the difference between vaginal (difference: 4.5% (95%CI: −1.6, 10.6)) or via cesarean (3.6% (95%CI: −3.1, 10.3) did not reach statistical significance. Also, adverse labor outcomes such as incidence of shoulder dystocia, postpartum hemorrhage, manual placenta extraction, and third/fourth degree perineal lacerations; and neonatal outcomes were no different. However, maternal hypotension and motor blockade was significant in the routine epidural analgesia group.

Combined spinal-epidural analgesia shortens labor

There are only six randomized trials where the effects of combined spinal-epidural analgesia on labor were assessed. As shown in Table 2, combined spinal-epidural analgesia was compared to epidural analgesia in four trials and showed inconsistent effects on labor duration.

Table 2.

Duration first stage of labor

| Study | CSE | Epidural | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tsen, 1999 | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 5.1 ± 2.6 | P <0.05 |

| Norris, 2001 | 10.0 | 9.8 | NS |

| Cortes, 2007 | 1.5 | 1.55 | 0.90 |

| Frigo, 2011 | 4.01 ± 1.43 | 4.60 ± 1.39 | 0.043 |

Reported in hours (mean ± SD). CSE=combined spinal-epidural; NS=not significant.

Specifically, Tsen and colleagues43 and Frigo and colleagues44 found significantly shorter labor when combined spinal-epidural analgesia was used. No effect on labor duration was found by the other investigators45,46. Combined spinal-epidural analgesia when compared to intravenous opioids was associated with significantly shorter labor in one study and longer labor in the other30,47 (Table 3). The major limitation of these trials was absence of length of labor as a primary outcome.

Table 3.

Comparison of combined spinal-epidural to intravenous analgesia. Length of First Stage of Labor

| Study | CSE | IV Analgesia | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wong, 2005 | 4.91 | 6.42 | <.0001 |

| Gambling, 1998 | 5.0 ± 3.3 | 4.0 ± 3.1 | 0.0001 |

Reported in hours (mean ± SD) CSE=combined spinal-epidural

Continuous spinal analgesia during labor

Throughout this review, discussion of neuraxial analgesia was limited to the two most commonly used methods, continuous lumbar epidural and combined spinal-epidural analgesia. Again, there is renewed interest in continuous spinal analgesia during labor. Although interest is primarily in establishing safety and efficacy, it was incidentally noted that women experience acceleration of cervical dilation with this method. Although accelerated labor has been observed, a significant portion (42%) of women also had severe, transient headaches related to dural puncture that limited this technique’s popularity48. Additionally, some women developed debilitating cauda equina syndrome49. These sequelae were attributed to excessive diameter needles and micro-catheters using the “through-the-needle” approach. These issues have been surmounted during the early 2000’s with the redesign of the needles, larger diameter catheters, and use of the “over-the-needle” technique. Although Arkoosh and colleagues50 randomized 429 women to continuous spinal versus conventional epidural analgesia during labor, they found no difference in rate of complications or side effects. However, continuous spinal analgesia remains largely investigational. Moreover, this group did not study the effects of continuous spinal analgesia on labor progression.

The Future

Significant progress has been made in establishing the safety and efficacy of neuraxial analgesia for labor and delivery. Currently, the continuous lumbar epidural is the most widely used mode of pain control for labor and delivery, and is generally considered safe and effective. Combined spinal-epidural analgesia, being equally as safe51, is gaining popularity because of its ability to provide rapid analgesia with the potential benefit of shortening labor. However, current evidence lacks conviction to whether or not it shortens labor, rendering the findings suggestive at best. Accordingly, adequately powered randomized control trials are encouraged, preferably with length of labor being a primary outcome.

Continuous spinal analgesia offers rapid-onset pain relief and could possibly hasten the time to delivery; however, this method is not well studied. But with redesign of equipment and subsequent modification of technique, future studies establishing its safety and efficacy are now possible and should be performed as well.

Combined spinal-epidural analgesia and continuous spinal analgesia may be the future of pain management in labor and delivery. Future studies could yield positive results that would have significant personal, societal, and economical benefits on labor progression and perhaps change the practice of pain relief in obstetrics.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Erica Grant is supported by the Center for Translational Medicine, NIH/NCATS Grant Number KL2TR000453.

This study is IRB exempt: A review article.

Footnotes

Authors have no disclosures.

EG performed extensive literature review, prepared the manuscript, and has approved final manuscript.

WT assisted with manuscript preparation and has approved final manuscript.

MC assisted with manuscript preparation and has approved final manuscript.

DM assisted with manuscript preparation and has approved final manuscript.

KL assisted with manuscript preparation and has approved final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Erica N. Grant, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390-9068

Weike Tao, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390-9068.

Margaret Craig, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390-9068.

Donald McIntire, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390-9032.

Kenneth Leveno, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390-9032.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(3):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble AD, de Vere RD. Epidural analgesia in labour. British Medical Journal. 1970;2(5704):296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5704.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May D, de Vere RD. Epidural analgesia in labour. British Medical Journal. 1976;2(6041):944. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6041.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osterman MJ, Martin JA. Epidural and spinal anesthesia use during labor: 27-state reporting area, 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59(5):1–13. 16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Leveno K. Regional analgesia and progress of labor. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;46(3):633–645. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200309000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Driscoll K, Jackson R, Gallagher J. Prevention of prolonged labour. British Medical Journal. 1969;2:477–480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5655.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman E. The graphic analysis of labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1954;68:1568–1575. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(54)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman E. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1955;6:567–589. doi: 10.1097/00006250-195512000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman E. Dysfunctional labor. In: Cohen WR, Friedman EA, editors. Management of Labor. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1983. pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dystocia and augmentation of labor. ACOG Practice Bulletin No.49. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102:1445–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Landy H, Branch DW, Burkman R, Haberman S, Gregory KD, et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116(6):1281–1287. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham FG, Leveno K, Bloom S, Hauth J, Rouse D, Spong C. Williams Obstetrics. 23rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. Abnormal labor; pp. 464–489. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Troendle J, Mikolajczyk R, Sundaram R, Beaver J, Fraser W. The natural history of the normal first stage of labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;115(4):705–710. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d55925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander J, Sharma S, McIntire D, Wiley J, Leveno K. Intensity of labor pain and cesarean delivery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2001;92:1524–1528. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200106000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panni M, Segal S. Local anesthetic requirements are greater in dystocia than in normal labor. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:957–963. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200304000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lederman RP, Lederman E, Work BA, McCann DS. The relationship of maternal anxiety, plasma catecholamines, and plasma cortisol to progress in labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1978;132(5):495–500. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(78)90742-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thornton C, Carrie L, Sayers L, Anderson A, Turnbull A. A comparison of the effect of extradural and parental analgesia on maternal plasma cortisol ceoncentrations during labor and the puerperium. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1976;83:631–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1976.tb00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shnider S, Abboud T, Artal R, Henriksen E, Stefani S, Levinson G. Maternal catecholamines decrease during labor after lumbar epidural anesthesia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;147(1):13–15. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour (Review) The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub3. CD000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jouppila R, Hollmén A. The effect of segmental epidural analgesia on maternal and foetal acid-base balance, lactate, serum potassium and creatine phosphokinase during labour. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1976;20(3):259–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1976.tb05038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longo LD, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, Forster RE. Placental CO2 transfer after fetal carbonic anhydrase inhibition. American Journal of Physiology. 1974;226(3):703–710. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.226.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons S, Cyna A, Dennis A, Hughes D. Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural analgesia in labour (Review) The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;18(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003401.pub2. CD003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorp JA, Hu DH, Albin RM, McNitt J, Meyer BA, Cohen GR, Yeast JD. The effect of intrapartum epidural analgesia on nulliparous labor: a randomized, controlled, prospective trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169(4):851–858. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90015-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nageotte M, Larson D, Rumney P, Sidhu M, Hollenbach K. Epidural analgesia compared with combined spinal-epidural analgesia during labor in nulliparous women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(24):1715–1719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chestnut D, McGrath J, Vincent R, Penning DH, Choi WW, Bates JN, McFarlane C. Does early administration of epidural analgesia affect obstetric outcome in nulliparous women who are in spontaneous labor. Anesthesiology. 1994;80(6):1201–1208. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chestnut D, Vincent R, McGrath J, Choi W, Bates J. Does early administration of epidural analgesia affect obstetric outcome in nulliparous women who are receiving intravenous oxytocin. Anesthesiology. 1994;80(6):1193–1200. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199406000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luxman D, Wolman I, Groutz A, Cohen JR, Lottan M, Pauzner D, David MP. The effect of early epidural block administration on the progression and outcome of labor. International. Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 1998;7(3):161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0959-289x(98)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vahratian A, Zhang J, Hasling J, Troendle J, Klebanoff M, Thorp J. The effect of early epidural versus early intravenous analgesia use on labor progression: a natural experiment. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(1):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohel G, Gonen R, Vaida S, Barak S, Gaitini L. Early versus late initiation of epidural analgesia in labor: does it increase the risk of cesarean section? a randomized trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;194(3):600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong C, Scavone B, Peaceman A, McCarthy RJ, Sullivan JT, Diaz NT, Yaghmour E, Marcus RJ, Sherwani SS, Sproviero MT, Yilmaz M, Patel R, Robles C, Grouper S. The risk of cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given in early versus late in labor. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(7):655–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang F, Shen X, Guo X, Peng Y, Gu X. Epidural analgesia in the latent phase of labor and the risk of cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(4):871–880. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b55e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wassen MM, Zuijlen J, Roumen FJ, Smits LJ, Marcus MA, Nijhuis JG. Early versus late epidural analgesia and risk of instrumental delivery in nulliparous women: A systematic review. BJOG. 2011;118(6):655–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pain relief during labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;104(1):213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bloom SL, McIntire DD, Kelly MA, Beimer HL, Burpo RH, Garcia MA, Leveno KJ. Lack of effect of walking on labor and delivery. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(2):76–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390203. 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallejo M, Firestone L, Mandell G, Francisco J, Makishima S, Ramanathan S. Effect of epidural analgesia with ambulation on labor duration. Anesthesiology. 2011;95(4):857–861. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breen T, Shapiro T, Glass B, Foster-Payne D, Oriol N. Epidural anesthesia for labor in an ambulatory patient. Obstetric Anesthesia. 1993;77(5):919–924. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collis R, Harding S, Morgan B. Effect of maternal ambulation on labour with low-dose combined spinal-epidural. Anaesthesia. 1999;54(6):535–539. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds S, Hellman L, Bruns P. Patterns of uterine contractility in women during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology Survery. 1948;3(5):629–645. doi: 10.1097/00006254-194810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fairlie F, Phillips G, Andrews B, Calder A. An analysis of uterine activity in spontaneous labour using a microcomputer. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988;(95):57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bates R, Helm C, Duncan A, Edmonds D. Uterine activity in the second stage of labour and the effect of epidural analgesia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1985;92(12):1246–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb04870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter S, Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Hands and knees posture in late pregnancy or labour for fetal malposition (lateral or posterior) Cochrane Database System. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001063.pub3. Rev.4,CD001063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wassen M, Smits L, Scheepers H, Marcus M, Van Neer J, Nijhuis J, et al. Routine labour epidural analgesia versus labour analgesia on request: a randomised non-inferiority trial. BJOG. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12854. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsen L, Thue B, Datta S, Segal S. Is combined spinal-epidural analgesia associated with more rapid cervical dilation in nulliparous patients when compared with conventional epidural analgesia? Anesthesiology. 1999;91:907–908. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frigo M, Larciprete G, Rossi F, Fusco P, Todde C, Jarvis S, Panetta V, Celleno D. Rebuilding the labor curve during neuraxial analgesia. Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2011;11:1532–1539. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norris M, Fogel S, Conway-Long C. Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural labor analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:913–920. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200110000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortes C, Sanchez C, Oliveira A, Sanchez F. Labor analgesia: a comparative study between combined spinal-epidural anesthesia versus continuous epidural analgesia. Revista Brasileira de Anesthesiologia. 2007;57:45–51. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942007000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gambling DR, Sharma SK, Ramin SM, Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Wiley J, Sidawi JE. A randomized study of combined spinal-epidural analgesia versus intravenous meperidine during labor: impact on cesarean delivery rate. Anesthesiology. 1998;89(6):1336–1344. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199812000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinebaugh M, Lang W. Continuous spinal anesthesia for labor and delivery: a preliminary report. Annals of Surgery. 1944;120(2):129–142. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194408000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rigler M, Drasner K, Krejcie T, Yelich S, Scholnick F, DeFontes J, Bohner D. Cauda equina syndrome after continuous spinal anesthesia. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1991;72(3):275–281. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arkoosh V, Palmer C, Yun E, Sharma SK, Bates JN, Wissler RN, Buxbaum JL, Nogami WM, Gracely EJ. A randomized, double-masked, multicenter comparison of the safety of continuous intrathecal labor analgesia using a 28-gauge catheter versus continuous eppidural labor analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(2):286–298. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000299429.52105.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skupski D, Abramovitz S, Samuels J, Pressimone V, Kjaer K. Adverse effects of combined spinal-epidural versus traditional epidural analgesia. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;106(3):242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]