Summary

Antithrombin (AT) is a protein of the serpin superfamily involved in regulation of the proteolytic activity of the serine proteases of the coagulation system. AT is known to exhibit anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective properties when it binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on vascular cells. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) plays an important cardioprotective role during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion (I/R). To determine whether the cardioprotective signaling function of AT is mediated through the AMPK pathway, we evaluated the cardioprotective activities of wild-type AT and its two derivatives, one having high affinity and the other no affinity for heparin, in an acute I/R injury model in C57BL/6J mice in which the left anterior descending coronary artery was occluded. The serpin derivatives were given 5 min before reperfusion. The results showed that AT-WT can activate AMPK in both in vivo and ex vivo conditions. Blocking AMPK activity abolished the cardioprotective function of AT against I/R injury. The AT derivative having high affinity for heparin was more effective in activating AMPK and in limiting infraction, but the derivative lacking affinity for heparin was inactive in eliciting AMPK-dependent cardioprotective activity. Activation of AMPK by AT inhibited the inflammatory c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) pathway during I/R. Further studies revealed that the AMPK activity induced by AT also modulates cardiac substrate metabolism by increasing glucose oxidation but inhibiting fatty acid oxidation during I/R. These results suggest that AT binds to HSPGs on heart tissues to invoke a cardioprotective function by triggering cardiac AMPK activation, thereby attenuating JNK inflammatory signaling pathways and modulating substrate metabolism during I/R.

Introduction

As the leading cause of death ranked by the World Health Organization, ischemic heart disease is caused by the reduction of the coronary blood supply to the myocardium. Treatment strategies for acute cardiac ischemia include primary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass surgery, and the use of anticoagulant and thrombolytic drugs which are all aimed at returning blood flow back to the ischemic area (1). Although increased blood flow aids in rapid restoration of energy, nevertheless, the irreversible cell damage caused by reperfusion is the main risk of these approaches. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) plays a pivotal role in intracellular adaptation to energy stress during myocardial ischemia (2). It has been demonstrated that the activation of cardiac AMPK is essential for accelerating ATP generation, attenuating ATP depletion and protecting the myocardium against post-ischemic cardiac dysfunction and apoptosis (3–5). Thus, a number of studies have shown that the physiological or pharmacological activation of AMPK can decrease cardiac necrosis caused by I/R injury (6–8)

There is increasing evidence that intracellular signaling responses initiated by the natural anticoagulant pathways, antithrombin (AT) and protein C systems, play critical roles in protecting the heart against I/R injury (9–12). AT is a serine protease inhibitor of the serpin superfamily (13), which regulates the proteolytic activities of procoagulant proteases of both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways (14). However, in addition to its anticoagulant activity, AT also possesses potent anti-inflammatory activities (12). The anticoagulant activity of AT is primarily mediated through the exposed reactive center loop of the serpin covalently modifying the active site residue of procoagulant proteases, and thereby trapping them in the form of irreversible inactive complexes incapable of interacting with their substrates (14). By contrast, the anti-inflammatory activity of AT has been shown to be mediated through the serpin interacting with vascular heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) via its basic D-helix independent of protease inhibition (9,12,15). The D-helix of AT is the same site to which the antithrombotic therapeutic heparins bind in order to facilitate the rapid recognition and inhibition of thrombin and other coagulation proteases by the serpin (16). It has been hypothesized that AT binds via its D-helix to vessel wall HSPGs (17), thereby inducing synthesis of prostacyclin (PGI2) and inhibition of NF-kB in vascular endothelial cells (18). Several studies have demonstrated that the PGI2-mediated protective function for AT can decrease liver, renal, and intestinal I/R injury (10,19–21). We also recently demonstrated that AT can elicit cardioprotective signaling responses through D-helix-dependent interaction with vascular HSPGs (18). Although the mechanism of heparin-dependent anticoagulant function of AT has been extensively studied and is relatively well understood, the HSPG-dependent cardioprotective signaling mechanism of AT during I/R injury remains unknown.

In light of a cardioprotective role for AMPK, we investigated whether AT, through interaction with vascular HSPGs, can activate AMPK to exert a cardioprotective function during I/R injury. The results demonstrate that the HSPG binding-dependent AT activation of the AMPK signaling pathway contributes to the cardioprotective function of the serpin during I/R injury.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Wild-type (WT) male C57BL/6J mice (12 weeks of age) and AMPK kinase dead (AMPK KD, expressing a KD α2 K45R mutation, driven in heart and skeletal muscles by the muscle creatine kinase promoter) (4), mice were used in the experiments. All animal protocols in this study were approved by the University at Buffalo-State University of New York Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

In vivo regional ischemia and infarct size measurement

Mice were anesthetized with 60 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbital (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, intubated and ventilated with a respirator (Harvard apparatus, Holliston, MA). After a left lateral thoracotomy, the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was occluded for 20 min (or 60 min for myocardial necrosis measurements) using an 8-0 nylon suture and gauze pad to prevent arterial injury, and then reperfused 15 min for immunoblotting or 4 hours for myocardial necrosis measurements. Vehicle (50% Glycerol/H2O) or AT (5 or 20 μg/g, Haematologic Technologies Inc. Essex Junction, VT) was administered via a tail vein injection 5 min before reperfusion. Successful occlusion of the LAD was confirmed by blanching of the left ventricle (LV) and rapid ST-segment elevation during coronary occlusion (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). The ischemic region of the LV was freeze-clamped in liquid nitrogen for biochemical analysis.

For infarct size measurements, hearts were excised, then perfused and stained for dual color. The non-necrotic tissue in ischemic area [area at risk (AAR)] was stained by 2, 3, 5- triphenyltetrazolium (TTC) into red, and the infract area showed in pale (5). The LAD was then re-occluded and stained by Evans blue dye to delineate non-ischemic region. Stained hearts were cut into 1 mm slices, photographed with a Leica microscope, and analyzed with National Institutes of Health Image J software. The myocardial infarct size was calculated as the ratio of the percentage of myocardial necrosis to the ischemic area at risk (AAR) as described (5,22).

Ex vivo global ischemia

Mice were heparinized (100 units i.p.) 10 min before being anesthetized. Isolated hearts were then retroperfused in the Langendorff perfusion system (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA) with Krebs-Henseleit buffer (KHB) containing 7mM glucose, 1% BSA, 0.4mM sodium oleate and 10μU/ml insulin and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. The water jacket bath was set to 38.7°C to keep the perfusion buffer at 37°C. For ex vivo ischemia model, isolated hearts were subjected to 20 min basal perfusion, followed by 25 min global, non-flow ischemia and then 30 min reperfusion. Hearts were freeze-clamped in liquid nitrogen for biochemical analysis. AT was given at the beginning of reperfusion.

Immunoblotting

Western blots were performed as previously described (5,22). Heart lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The antibodies for JNK, phosphor-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (p-JNK), phosphor-AMPK-Thr172 (p-AMPK), AMPKα, phosphor-Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (p-ACC), Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC), phosphor-c-Jun (p-Jun), c-Jun, phosphor- Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (p-eEF2), phosphor- Serine/threonine-protein kinase ULK1 (Ser555), were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). 4 Hydroxynonenal (4 HNE) was purchased from Abcam.

Fatty acid/glucose oxidation analysis

A working heart model was used to test the cardiac substrate (fatty acid and glucose) metabolism as described (4, 23). Isolated WT or AMPK KD hearts were subjected to 20 min perfusion followed by 10 min of global ischemia and 20 min of reperfusion. The water jacket bath was set to 38.7°C to keep the perfusion buffer at 37°C. The working heart preload was set up at 15 cm H2O, and the afterload was set at 80 cm H2O. The flow rate was kept at 15mL/min. The heart function was monitored by pressure transducer connected to aortic outflow. [9, 10]-3H-oleate (50μci/L) and 14C-glucose (20μci/L) labeled BSA buffer perfused into the heart through the pulmonary vein and pumped out through the aorta. Perfusate pumped out from aorta and outflowed from coronary venous was recycled and collected every 5 min to test the radioactivity. The fatty acid level was determined by the production of 3H2O from [9, 10]-3H-oleate. Metabolized 3H2O was separated from [9, 10]-3H-oleate by filtering through an anion exchange resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Glucose oxidation was measured by metabolized 14CO2 solved in buffer or gaseous (further solved in sodium hydroxide and sampled every 5 min). To separate 14CO2 from 14glocose, sulfuric acid was added into perfusate samples to release 14CO2. 3H and 14C signals were detected to discriminate metabolic products from fatty acid and glucose, respectively.

Isolation of cardiomyocytes

Mice were given 100 units (i.p.) of heparin (Sagent Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL) 10 min before being anesthetized with 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (i.p.) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Hearts were excised and retroperfused with the cardiomyocyte perfusion apparatus (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA). The perfusion buffer which is ventilated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and kept at 37°C, is a Ca2+-free Krebs–Henseleit based buffer (pH 7.3) containing 0.6 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM HEPES, 14.7 mM KCl, 1.7 mM MgSO4, 120.3 mM NaCl, 4.6 mM NaHCO3, 30 mM taurine, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime. After 5 min of stabilization, the heart was then digested with the same perfusion buffer containing 0.067 mg/mL Liberase Blendzyme 4 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 15 min. Hearts were then minced. Extracellular Ca2+ was added back to the cells to reach a final concentration of 1 mM. For normoxia approach, cardiomyocytes were subjected to pharmacological drug treatment with AT or surfen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 20 min at 37°C.

Permeability assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial (EA.hy926) cells (courtesy of Dr. C. Edgell from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC) were used to assess the protective activity of AT in a permeability assay as described (18). Briefly, confluent endothelial cells, with or without transfection with specific siRNA for heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase-1 (HS 3-OST-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), were incubated with AT-WT (150 μg/mL for 3h) before stimulating them with LPS (10 μg/mL for 4h). Cell permeability was quantitated by the spectrophotometric measurement of the flux of Evans blue-bound albumin across the cell monolayer using a modified 2-compartment chamber model as described (18).

Statistical analysis

Data was expressed as mean ± standard error. Data was analyzed with one-way ANOVA for measurement of statistical significance. For single- and multi-factorial analyses, post hoc test(s) were performed to measure the differences in individual groups of interest. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

AT stimulates AMPK phosphorylation in vivo and ex vivo

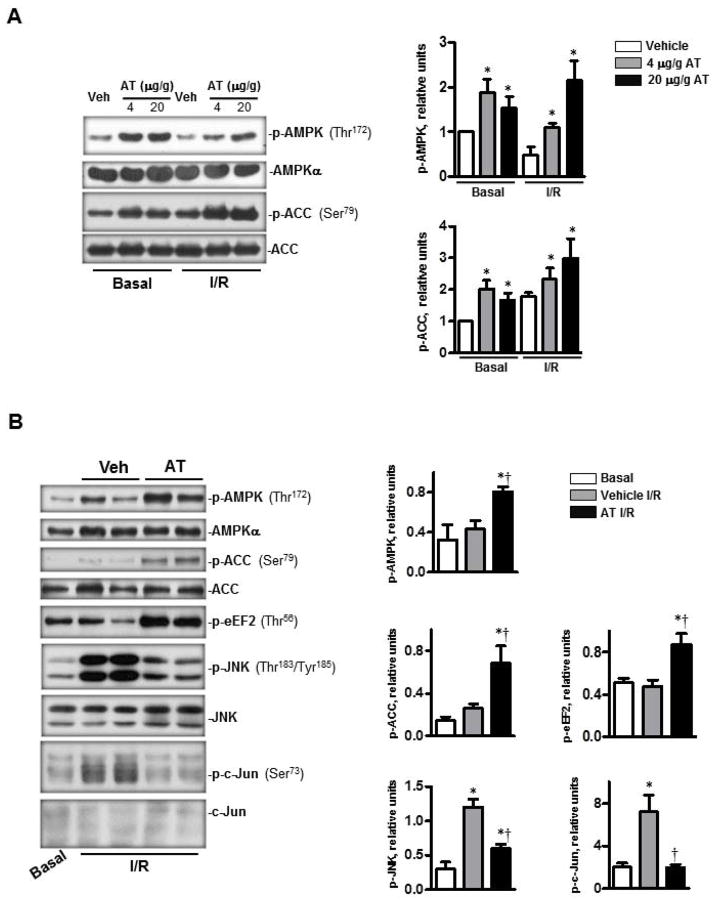

The activation of AMPK by ischemia is known to protect the heart against I/R injury by regulating downstream metabolic pathways including glycolysis (24), glycogen synthesis (25) glucose oxidation (26), fatty acid oxidation (27), protein synthesis (28) and autophagy (3,28). In light of our recent finding that AT can elicit cardioprotective responses during I/R injury (9), we investigated whether AT-mediated AMPK signaling contributes to the cardioprotective function of the serpin. Both in vivo and ex vivo I/R experiments were performed to test this hypothesis. The results showed that under basal conditions, the tail vein injection of AT (4 μg/g mice, 20 min before termination) activates AMPK by significantly elevating the phosphorylation of Thr172 on the α catalytic subunit of the kinase (Fig. 1A, p<0.05). A robust AT-mediated AMPK activation was also observed when the mouse hearts were subjected to LAD occlusion for 20 min followed by 15 min of reperfusion. In this case, an optimal level of phosphorylated AMPK (p-AMPK) in the left ventricular area was observed with an AT dose of 20 μg/g mice (p<0.05 vs. I/R Vehicle) (Fig. 1A). Under both basal and I/R conditions, the phosphorylation of the downstream effector of AMPK, acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (ACC), which is involved in fatty acid oxidation (24), was also significantly increased in AT-treated groups (Fig. 1A). Moreover, the isolated hearts were perfused in an ex vivo heart perfusion system by cannulating the aorta for basal perfusion for 20 min followed by 25 min of global non-flow ischemia and 30 min reperfusion. Interestingly, in addition to phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC, AT administration prior to reperfusion also significantly up-regulated the phosphorylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), a critical factor involved in the inhibition of protein synthesis (29) (Fig. 1B). Moreover, AMPK activation by AT was associated with the inhibition of I/R mediated phosphorylation of cardiac c-Jun and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inflammatory pathways (Fig. 1B, p<0.05). Taken together, results of both in vivo and ex vivo heart perfusion studies presented above indicate that AT activates the AMPK signaling pathway, thereby exerting a cardioprotective function against I/R injury.

Figure 1.

AT stimulated AMPK activation during in vivo basal and I/R and ex vivo I/R conditions. (A) AT, treated for 20 min at basal condition or 5 min before reperfusion during regional ischemia, induced phosphorylation of AMPK and phosphorylation of downstream acetyl CoA (ACC). The bar graphs (right panel) show the relative level of p-AMPK and p-ACC, respectively. (B) AT-treated (2.5 μg/mL) heart ex vivo at the beginning of reperfusion during global ischemia (25 min). AT increased the phosphorylation of AMPK, ACC and eEF2. AT treatment also inhibited the phosphorylation of JNK and its downstream protein c-Jun during ischemia (25 min) and reperfusion (30 min) (left panel). The bar graphs (right panel) show the relative levels of p-AMPK, p-ACC, p-eEF2, p-JNK and p-c-Jun, respectively. N=5 for basal and I/R condition; n=7 for I/R/AT condition; *p<0.05 vs. Basal Vehicle or I/R Vehicle; †p<0.05 vs. I/R Vehicle.

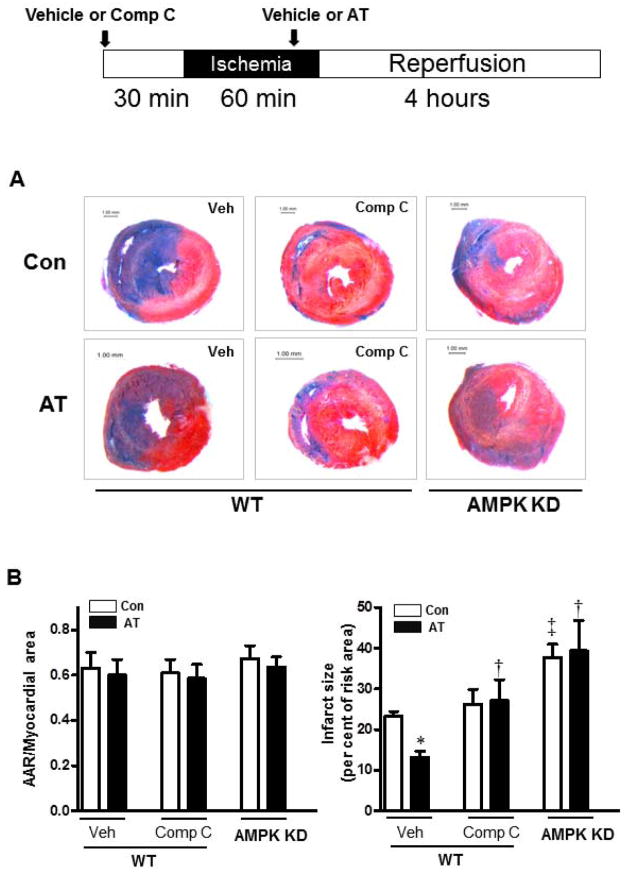

Inhibition of AMPK activation limits the cardioprotective activity of AT

To provide further support for the hypothesis that AMPK activation by AT leads to a cardioprotective effect during I/R injury, we pretreated mice with the AMPK inhibitor, Compound C (1 μg/g, subcutaneous injection) (30), for 30 min prior to LAD ligation-induced regional ischemia (60 min) followed by reperfusion (4 h). The results demonstrated that pretreatment with Compound C effectively abolishes the cardioprotective effect of AT against I/R damage (Fig. 2A and 2B, p<0.05). Furthermore, AT did not exhibit a significant cardioprotective effect in the AMPK kinase-dead (KD) mice during I/R (Fig. 2A and 2B). These results support the hypothesis that the activation of AMPK is a major contributor to AT’s cardioprotective effect against myocardial damage during I/R.

Figure 2.

Activation of AMPK by AT mediates its cardioprotection against myocardial infarction. Wild type (WT) mice were subjected to in vivo regional ischemia (60 min) followed by 4 hours reperfusion. AT (20 μg/g) or vehicle was administered 5 min prior to reperfusion, Compound C (1 μg/g, subcutaneous) or vehicle was given 30 min before ischemia as shown in the diagram. (A) Representative sections of the extent of myocardial infarction. (B) The ratio of the area at risk (AAR) to the total myocardial area (left bar graph) and the ratio of the infarction area to the AAR (right bar graph). Values are means ± SE from 4 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. WT Vehicle Control; †p<0.05 vs. WT Vehicle AT; ‡p<0.05 vs. WT Vehicle Control.

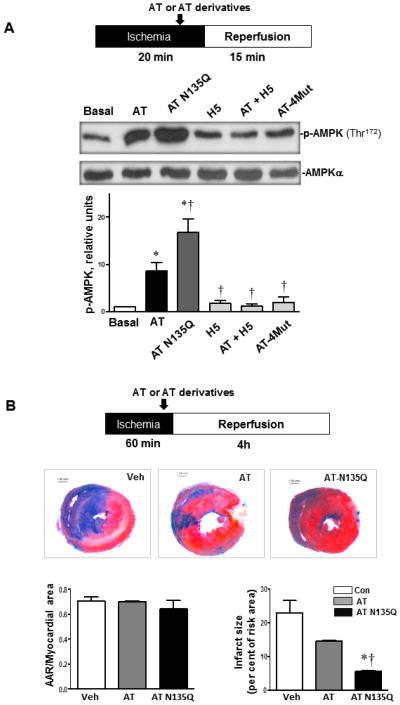

AT activates AMPK via D-helix dependent interaction with HSPGs

It is known that the interaction of the basic D-helix of AT with vascular HSPGs is responsible for the protective signaling activity of the serpin (16–18). To determine whether a similar mechanism is involved in the AT activation of AMPK, the activity of two AT derivatives which have different affinities for heparin was analyzed in the same in vivo assay system described above. The first derivative is a D-helix mutant of AT (AT-4Mut) which is known to exhibit no affinity for heparin (32). The second derivative, in which Asn-135 of the D-helix has been replaced with a Gln (AT-N135Q), exhibits markedly higher affinity for heparin due to this residue missing a post-translationally attached carbohydrate side chain in the native serpin. This AT derivative mimics the heparin-binding properties of the β isoform of the serpin. It is known that AT circulates in plasma in two α and β isoforms (33). The β-AT isoform, which represents only 5–10% of plasma AT, lacks the carbohydrate at Asn-135 and thus binds heparin with ~5-fold higher affinity (33). Consistent with the HSPG-dependent protective signaling mechanism of the serpin, the AT-N135Q derivative activated AMPK markedly better than wild-type AT (Fig. 3A, p<0.05). By contrast, the AT-4Mut derivative did not show any induction of AMPK activation and a synthetic therapeutic AT-binding pentasaccharide (H5), which is known to bind the D-helix of AT, abrogated the elevated AT-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 3A). Further support for our hypothesis is provided by the observation that, relative to AT-WT, AT-N135Q exhibited significantly higher activity in limiting the infarct size (Fig. 3B, p<0.05). These results clearly indicate that the D-helix dependent interaction of AT with HSPGs on cardiac tissues is responsible for increased AMPK activation during I/R injury.

Figure 3.

The capacity of AT to activate AMPK correlates with its affinity for heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). (A) Hearts were subjected to 20 min ischemia followed by 15 min reperfusion in vivo or sham operation (Basal). AT (4 μg/g) or AT derivatives (all 4 μg/g) were administrated via the tail vein 5 min prior to reperfusion under ischemia (20 min) followed by reperfusion (15 min). The hearts were homogenized for immunoblotting with p-AMPK (Thr172) or AMPKα antibodies. (B) The extent of myocardial infarction (60 min ischemia) with vehicle, wild-type AT or AT-N135Q (4 μg/g). N= 4 for basal and I/R with AT derivative; n=5 for I/R with wild-type AT. *p<0.05 vs. Basal; †p<0.05 vs. AT.

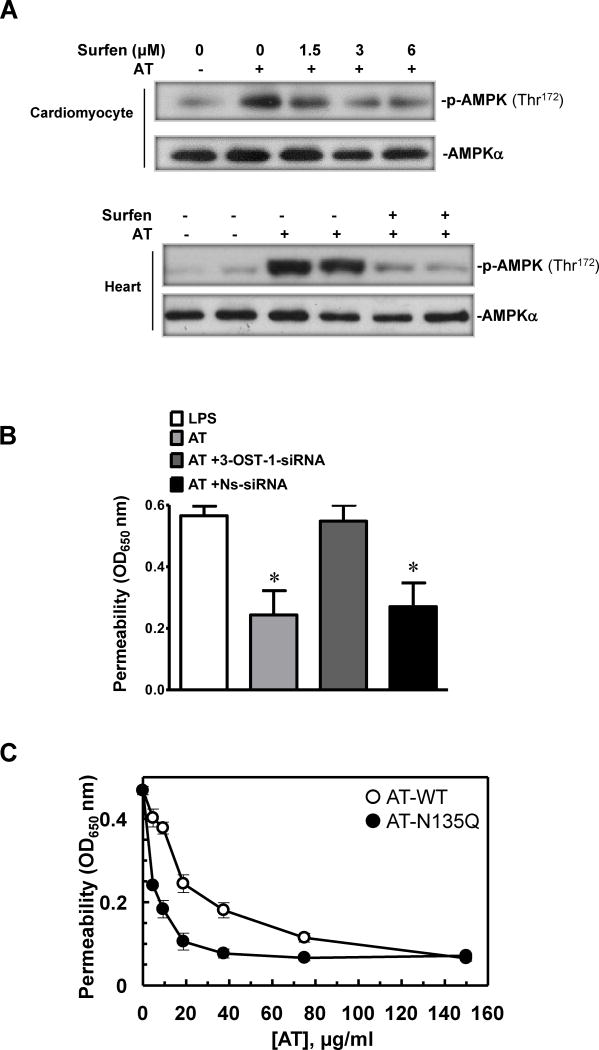

AT exerts its protective effect through interaction with 3-OS containing HSPGs

It has been hypothesized that a small subgroup of HSPGs containing a 3-O-sulfate (3-OS) moiety, which has high affinity for AT (HSAT+), may act as a receptor for AT to mediate the anti-inflammatory function of the serpin (15). To investigate the hypothesis that a similar mechanism may be involved in AT activating AMPK, cardiomyocytes were pretreated with the HS antagonist, surfen (31). AT-treated cardiomyocytes showed elevated AMPK activation, however, this activation was blocked after pretreating cardiomyocytes with surfen (Fig. 4A upper panel). The surfen blockade of AT-induced AMPK activation in isolated heart during the reperfusion stage further validated our hypothesis that AT, through interaction with HSPGs, stimulates AMPK activation in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4A lower panel).

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of AMPK by AT is mediated through interaction with HSPGs. (A) The heparin sulfate antagonist, surfen, inhibits AMPK activation by AT in cardiomyocytes and isolated heart. Upper panel, cardiomyocytes were treated with AT (5μg/mL) and surfen at different doses for 20 min. Lower panel, ex vivo global ischemia (25 min) followed by 30 min reperfusion. AT (2.5 μg/mL) or AT plus equimolar concentration of surfen was administered 5 min prior to reperfusion. (B) The barrier protective activity of AT is inhibited by the siRNA knockdown of HS 3-OST-1. The barrier protective activity of AT (150 μg/mL, 4h) in LPS-stimulated (10 μg/mL for 4h) endothelial cells was measured before and after treatment of cells with the non-specific (NS) or specific siRNA for heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase-1 (0.2 μg/mL, 3h) as described under Materials and Methods. *p<0.05 vs. LPS alone. (C) The same as B except that cell permeability in response to LPS was monitored as function of increasing concentrations of either AT-WT (○) or AT-N135Q (●).

We previously demonstrated that AT exerts a potent protective effect in endothelial cells stimulated with LPS. Thus, we showed that AT inhibits LPS-enhanced permeability of endothelial cells by a concentration dependent mechanism (18). To provide further support for the hypothesis that the interaction of AT with the high affinity HSPGs containing 3-O-sulfate (3-OS) is responsible for the protective activity of the serpin, we used siRNA for heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase-1 (HS 3-OST-1), which is the enzyme known to be responsible for the synthesis of 3-OS containing HSPGs in vascular endothelial cells (15,17), before incubation with AT and stimulation of cells with LPS. As presented in Fig. 4B, the siRNA knockdown of HS 3-OST-1 gene in endothelial cells effectively abrogated the protective activity of AT in response to LPS, suggesting that the interaction of AT with the 3-OS containing HSPGs (HSAT+) is required for the protective signaling function of the serpin. In agreement with this hypothesis, the optimal concentration of β-AT (AT-N135Q) required to achieve a barrier protective activity in endothelial cells was also significantly reduced (Fig. 4C).

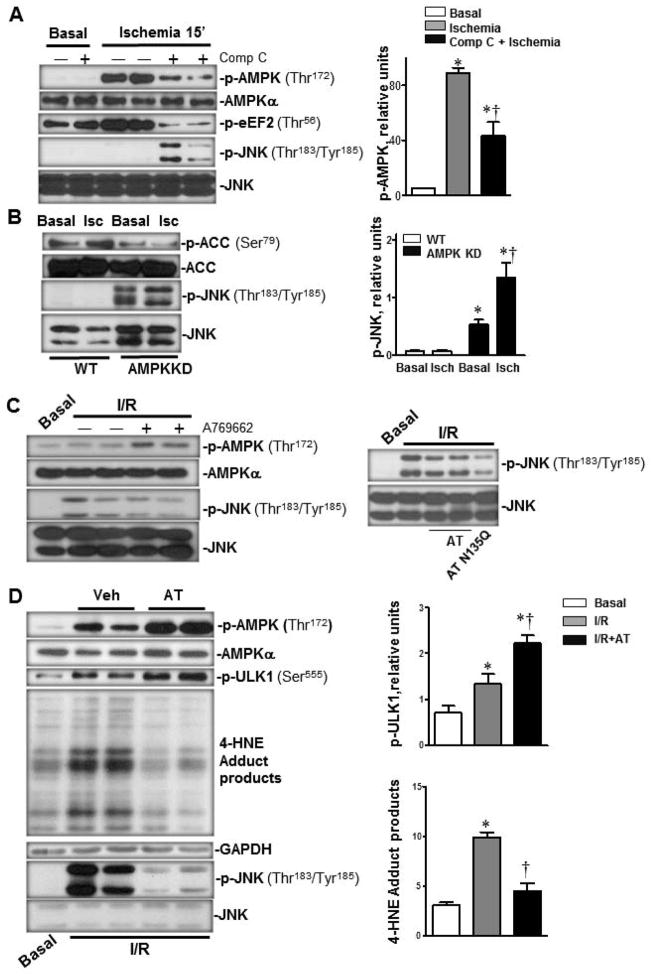

Activation of AMPK by AT inhibits the inflammatory JNK signaling during I/R

To explore the intrinsic relationship between AT-mediated activation of AMPK signaling and modulation of proinflammatory responses, we analyzed the effect of AT on the induction of both AMPK and JNK signaling pathways in the heart during I/R. There was a strong AMPK activation but no JNK phosphorylation in response to ischemic stress in the heart (p<0.05), interestingly, we discovered that pretreatment with the AMPK inhibitor, Compound C, which significantly inhibits AMPK phosphorylation induced by ischemia (p<0.05), markedly elevated JNK phosphorylation in the heart during ischemia (Fig. 5A, upper panel, p<0.05). Moreover, the AMPK kinase dead (KD) heart demonstrated much higher JNK phosphorylation than did the wild-type heart (Fig. 5B, lower panel, p<0.05) and ischemic stress further augmented JNK phosphorylation in the AMPK-KD heart (p<0.05 versus AMPK-KD basal, Fig. 5B, lower panel). Consistent with AMPK modulating JNK signaling, mice pretreated with the AMPK specific activator, A769662 (29), attenuated cardiac JNK phosphorylation induced by I/R (Fig. 5C, left panel). Likewise, AT-N135Q, which activates AMPK better than AT-WT, exhibited a more effective inhibition of I/R-induced JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 5C, right panel). These results indicate that AT-mediated activation of cardiac AMPK down-regulates the JNK inflammatory signaling pathway to protect the heart from damage caused by I/R.

Figure 5.

Activation of cardiac AMPK inhibits JNK phosphorylation during I/R. (A) I/R triggered phosphorylation of AMPK but not JNK, The inhibition of AMPK with Compound C during ischemia (0.1 μg/g via the tail vein 30 min prior to ischemia) inhibited AMPK activation which was associated with the downstream JNK phosphorylation (upper panels). Immunoblotting of the heart homogenates were performed with antibodies against p-AMPK (Thr172), AMPKα, p-eEF2 (Thr56), p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and JNK (left). The bar graphs show the relative level of p-AMPK (right). Values are means ± SE form 3–5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. Basal; †p<0.05 vs. ischemia alone. (B) Immunoblotting of homogenates from AMPK kinase dead (KD) hearts demonstrated higher levels of JNK and lower levels of ACC phosphorylation under both basal and ischemic stress conditions (left). The bar graphs show the relative level of p-JNK (right). Values are means ± SE form 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. WT Basal; †p<0.05 vs. AMPK KD ischemia. (C) Activation of AMPK by either the AMPK activator or AT administration inhibited JNK phosphorylation caused by ischemia (20 min) and reperfusion (15 min) in the hearts. The AMPK activator, A769662 (left panel), AT-WT or AT N135Q (right panel) was administrated via the tail vein injection 5 min prior to reperfusion under ischemia (20 min) followed by reperfusion (15 min). Immunoblotting of the heart homogenates were performed with antibodies to p-AMPK (Thr172), AMPKα, p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and JNK. (D) Activation of AMPK by AT reduces oxidative stress via augmenting autophagy during ischemia (20 min) and reperfusion (15 min) in the heart. AT (4 μg/g) was administrated 5 min before reperfusion. Immunoblotting of the heart homogenates were performed with antibodies to p-ULK1 (Ser555), p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), JNK, GAPDH and 4 Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE). N=5 for basal and I/R conditions; N=7 for I/R/AT condition; *p<0.05 vs. Basal; †p<0.05 vs. I/R alone.

To further explore the mechanism by which activation of AMPK by AT inhibits JNK phosphorylation, we measured the level of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) which reflects the intracellular oxidative stress status (34–36). The results showed that AT administration significantly inhibits the 4-HNE level caused by I/R (Fig. 5D). Intriguingly, AT treatment also augments the AMPK downstream phosphorylation of ULK1, a known modulator of autophagy, which is involved in the elimination of damaged organelles in stressed cells (37) (Fig. 5D).

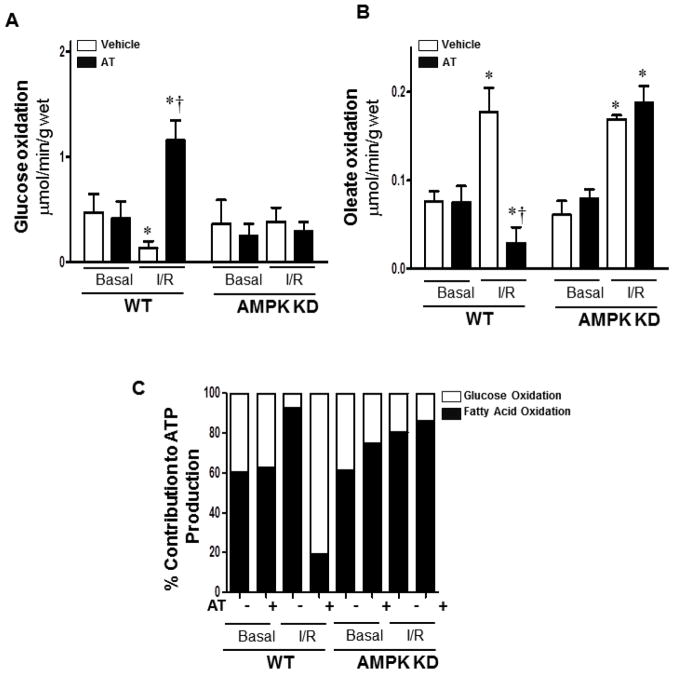

AT modulates glucose and fatty acid oxidation during I/R

One of the most important functions of cardiac AMPK is to increase energy production during stress conditions (24,25). Activated AMPK can achieve this important physiological process by modulating substrate metabolism through several different mechanisms. AMPK can 1) accelerate fatty acid uptake and oxidation (38), 2) increase glucose uptake (39), and 3) stimulate glycolysis (40). Therefore, the next question was whether the activation of AMPK by AT in the heart modulates substrate metabolism during I/R. Glucose oxidation was measured by the amount of [14C] glucose metabolism into 14CO2 in the ex vivo working hearts (27). Fatty acid oxidation was measured by the incorporation of [9, 10-3H] oleate into 3H2O (27). The results showed that AT treatment significantly shifts the increased oleate oxidation (Fig. 6B and 6C, p<0.05) in favor of increased glucose oxidation (Fig. 6A and 6C, p<0.05) during I/R, however, it does not affect the rate of glucose and oleate oxidation under basal perfusion conditions (Fig. 6A, 6B and 6C). Moreover, this metabolic-shift function of AT was abolished in the AMPK-KD heart perfusion experiments. Thus, AT did not show a significant effect on the regulation of substrate metabolism in the AMPK-KD hearts during I/R(Fig. 6), supporting the hypothesis that AT-mediated AMPK activation exerts a cardioprotective effect through the modulation of energy substrate metabolism during I/R. The cardiac pumping capacity measured in the working heart perfusion system indicated that there is no significant changes in cardiac pumping functions that can be attributed to the AT treatment (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 6.

AT treatment augments glucose oxidation and attenuates fatty acid oxidation in the heart during I/R. (A/B) Glucose/oleate oxidation in the isolated heart. After balancing 20 min, isolated wild type (WT) or AMPK KD hearts were subjected to 10 min of ischemia and 20 min of reperfusion. Glucose oxidation was analyzed by measuring [14C] glucose metabolism into 14CO2. Fatty acid oxidation was measured by the incorporation of [9, 10-3H] oleate into 3H2O. (C) Relative percentage of ATP production from glucose and fatty acid oxidation. Values are means ± SE form 3 independent experiments for AT treatment, and 6 independent experiments for control. *p<0.05 vs. WT Basal Vehicle or AMPK KD Basal Vehicle, †p<0.05 vs. WT I/R Vehicle.

Discussion

Previous studies have established a protective role for AT in ameliorating myocardial necrosis during I/R injury (9). Results of this study for the first time demonstrate that AT may exert its cardioprotection against I/R injury through activation of AMPK signaling. The activation of AMPK by AT was associated with the inhibition of the pro-inflammatory JNK pathway in the injured heart. Our results further demonstrated that the AMPK-dependent downstream phosphorylation of ACC and eEF2, which are involved in fatty acid oxidation (ACC) and inhibition of protein synthesis, respectively (24,29), was enhanced by AT administration in the heart. Metabolic regulation of these pathways by AMPK is expected to save ATP consumption, thereby benefiting the heart’s contractility under I/R stress conditions. We previously demonstrated that AT also inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and JNK and the activation of the NF-κB pathway by inducing synthesis of PGI2 (9,18). The relationship between the AT elevation of PGI2 synthesis and its activation of AMPK in the heart during I/R is not known nor is the extent of the contribution of each one of these pathways to the anti-inflammatory properties of AT.

The results herein, for the first time, showed that AT can inhibit I/R-mediated JNK phosphorylation by the activation of the cardiac AMPK. The in vivo animal experiments showed that AT treatment stimulates cardiac AMPK activation under both physiological and I/R conditions. AMPK has emerged as a key factor in regulating substrate metabolism to protect the stressed heart from I/R injury. In support of this, the attenuation of the induction of cardiac AMPK, by either a pharmacological approach of inhibiting it with Compound C or by a genetic approach of overexpressing the dominant negative catalytic α2 subunit of AMPK in the heart, was associated with elevated I/R-induced pro-inflammatory JNK phosphorylation. On the other hand, the AMPK activator, A-769662, markedly inhibited the stimulation of JNK phosphorylation during I/R. These results further indicate that the activation of cardiac AMPK plays a major anti-inflammatory role in modulating the JNK inflammatory signaling pathway in the I/R-stressed heart. Thus, the anti-inflammatory JNK inhibitory activity of AT during I/R is mediated, at least partially, through the activation of AMPK signaling.

There is evidence that the phosphorylation of the mammalian protein, ULK1, by AMPK is critical for the regulation of autophagy (29,37). Interestingly, the AT treatment was also associated with augmentation of ULK1 phosphorylation during I/R, indicating that modulation of autophagy by AT may be beneficial since it can provide needed energy to the ischemic heart through this alternative metabolic pathway. Furthermore, the AT-mediated AMPK activation was associated with the inhibition of 4-HNE modified proteins. 4-HNE is an α,β-unsaturated hydroxyalkenal that is formed by lipid peroxidation. The elevated level of 4-HNE modified proteins is a good indicator of oxidative stress-mediated ROS formation, which also appears to be effectively inhibited by AT in the ischemic heart.

Under normal physiological conditions, fatty acid β-oxidation is responsible for the major source of energy in the heart, supplying as much as 50–70% of the acetyl CoA-derived ATP. By contrast, glycolysis usually contributes <10% of the overall ATP (24). However, because of insufficient oxygen supply during myocardial ischemia, glucose becomes the main energy source via glycolysis (25). Increased fatty acid oxidation at the beginning of reperfusion can be associated with in a sudden influx of oxygen levels, which may result in increased generation of ROS formation and cardiomyocyte damage (27). An interesting observation of this study was the finding that AT treatment effectively shifted the cardiac substrate metabolism from increased oleate oxidation in favor of increased glucose oxidation during I/R. This metabolic-shift action of AT was mediated through the activation of cardiac AMPK since AT had no metabolic-shift effect on the AMPK KD hearts. The metabolic-shift effect of AT can contribute to its cardioprotective effect by decreasing oleate oxidation, thereby limiting the amount of ROS generation that can cause cardiomyocyte damage during reperfusion. In line with the beneficial effect of accelerated glucose oxidation and decreased fatty acid oxidation in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion, several fatty acid β-oxidation inhibitors including trimetazidine and ranolazine have emerged as therapeutic drugs which have proven to be effective against ischemic heart disease (41,42). Thus, as an AMPK agonist capable of modulating cardiac metabolism, AT may have a therapeutic potential for the treatment of ischemic heart disease.

Finally, the observation that the AT-4Mut, which cannot interact with heparin, did not activate AMPK suggests that the D-helix dependent interaction of AT with cell surface HSPGs is responsible for the cardioprotective effect of the serpin during I/R. Further support for this hypothesis was provided by the observation that the AT-N135Q mutant, which binds to heparin with higher affinity, activated AMPK with significantly higher potency and exhibited a significantly higher cardioprotective activity (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the high affinity AT-binding pentasaccharide inhibited the AMPK activating property of the serpin. These results suggest that the signaling activity, but not the anticoagulant activity of AT, is solely responsible for the AMPK-dependent cardioprotective activity of AT. Previous studies have indicated that AT interaction with a small fraction of vascular HSPGs that contain 3-O-sulfate modification (HSAT+) may be responsible for the anti-inflammatory signaling activity of the serpin. In support of this hypothesis, it has been demonstrated that the knockout mutant of mice lacking the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of 3-OS (HS 3-OST-1) exhibit normal hemostatic function, however, they show a proinflammatory phenotype and, unlike wild-type mice, they do not respond to AT if challenged with LPS (15). The observation of this study that the siRNA knockdown of HS 3-OST-1 abrogated the signaling function of AT in the LPS-stimulated endothelial cells supports the hypothesis that the interaction of AT with 3-OS containing HSPGs may be responsible for the AMPK-dependent protective activity of the serpin. Thus, the AT-N135Q mutant warrants further investigation for its therapeutic potential in preventing cardiac I/R injury.

Supplementary Material

A. What is known about this topic?

Antithrombin is a plasma serpin inhibitor that regulates the proteolytic activity of procoagulant proteases of the clotting cascade.

In addition to its anticoagulant activity, antithrombin also possesses antiinflammatory properties.

We have demonstrated that antithrombin exerts a cardioprotective activity against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) occlusion model by an unknown mechanism.

B. What does this paper add?

This paper demonstrates that antithrombin activates AMP-activated protein kinase in both in vivo and ex vivo conditions in the LAD injury model.

An antithrombin derivative having high affinity for heparin is more potent AMPK activator and exhibits better cardioprotective activity however a mutant lacking affinity for heparin has no cardioprotective activity and is not capable of activating AMPK.

Blocking the heparin-binding site of antithrombin by pentasaccharide abrogates the cardioprotective activity of the inhibitor.

These results suggest that antithrombin binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans to activate AMPK, thereby protecting the myocardium against post-ischemic cardiac dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Audrey Rezaie for proofreading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from NIH HL62526 and HL101917, the American Heart Association (12GRNT11620029 and 14IRG18290014), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31171121), and the American Diabetes Association (1-11-BS-92 and 1-14-BS-131).

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Ferdinandy P, Schulz R, Baxter GF. Interaction of cardiovascular risk factors with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, preconditioning, and postconditioning. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:418–458. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.06002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardie DG. Minireview: the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade: the key sensor of cellular energy status. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5179–5183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolinsky VW, Dyck JR. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in healthy and diseased hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2557–2569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00329.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell RR, 3rd, Li J, Coven DL, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates ischemic glucose uptake and prevents postischemic cardiac dysfunction, apoptosis, and injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:495–503. doi: 10.1172/JCI19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma H, Wang J, Thomas DP, et al. Impaired macrophage migration inhibitory factor-AMP-activated protein kinase activation and ischemic recovery in the senescent heart. Circulation. 2010;122:282–292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.953208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, et al. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through AMPK- and COX-2-dependent mechanisms. Nat Med. 2005;11:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Yang L, Rezaie AR, et al. Activated protein C protects against myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury through AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1308–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison A, Yan X, Tong C, et al. Acute rosiglitazone treatment is cardioprotective against ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating AMPK, Akt, and JNK signaling in nondiabetic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H895–902. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00137.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. Antithrombin is protective against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1020–1028. doi: 10.1111/jth.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoots IG, Levi M, van Vliet AK, et al. Inhibition of coagulation and inflammation by activated protein C or antithrombin reduces intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1375–1383. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000128567.57761.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esmon CT. Protein C anticoagulant pathway and its role in controlling microvascular thrombosis and inflammation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S48–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opal SM, Kessler CM, Roemisch J, Knaub S. Antithrombin, heparin, and heparan sulfate. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S325–331. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irving JA, Pike RN, Lesk AM, et al. Phylogeny of the serpin superfamily: implications of patterns of amino acid conservation for structure and function. Genome Res. 2000;10:1845–1864. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1478r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson ST, Swanson R, Raub-Segall E, et al. Accelerating ability of synthetic oligosaccharides on antithrombin inhibition of proteinases of the clotting and fibrinolytic systems. Comparison with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:929–939. doi: 10.1160/TH04-06-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shworak NW, Kobayashi T, de Agostini A, et al. Anticoagulant heparan sulfate to not clot--or not? Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;93:153–178. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)93008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin L, Abrahams JP, Skinner R, et al. The anticoagulant activation of antithrombin by heparin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14683–14688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcum JA, Rosenberg RD. Anticoagulantly active heparin-like molecules from vascular tissue. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1730–1737. doi: 10.1021/bi00303a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae JS, Rezaie AR. Mutagenesis studies toward understanding the intracellular signaling mechanism of antithrombin. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:803–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada N, Okajima K, Kushimoto S, et al. Antithrombin reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury of rat liver by increasing the hepatic level of prostacyclin. Blood. 1999;93:157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Inthorn D, et al. Antithrombin reduces leukocyte adhesion during chronic endotoxemia by modulation of the cyclooxygenase pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C98–C107. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.1.C98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozden A, Sarioglu A, Demirkan NC, et al. Antithrombin III reduces renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Res Exp Med (Berl) 2001;200:195–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong C, Morrison A, Yan X, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency augments cardiac dysfunction in type 1 diabetic murine cardiomyocytes. J Diabetes. 2010;2:267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makinde AO, Gamble J, Lopaschuk GD. Upregulation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase is responsible for the increase in myocardial fatty acid oxidation rates following birth in the newborn rabbit. Circ Res. 1997;80:482–489. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amr Moussa JL. AMPK in myocardial infarction and diabetes: the yin/yang effect. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2012;2:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison A, Li J. PPAR-gamma and AMPK--advantageous targets for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young LH, Li J, Baron SJ, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase: a key stress signaling pathway in the heart. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa R, Morrison A, Wang J, et al. Activated protein C modulates cardiac metabolism and augments autophagy in the ischemic heart. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1736–1744. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jefferson LS, Wolpert EB, Giger KE, et al. Regulation of protein synthesis in heart muscle. 3. Effect of anoxia on protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:2171–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach PJ. AMPK -> ULK1 -> autophagy. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3082–3084. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05565-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim AS, Miller EJ, Wright TM, et al. A small molecule AMPK activator protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuksz M, Fuster MM, Brown JR, et al. Surfen, a small molecule antagonist of heparan sulfate. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2008;105:13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805862105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Manithody C, Qureshi SH, et al. Contribution of exosite occupancy by heparin to the regulation of coagulation proteases by antithrombin. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:277–283. doi: 10.1160/TH09-08-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCoy AJ, Pei XY, Skinner R, et al. Structure of beta-antithrombin and the effect of glycosylation on antithrombin’s heparin affinity and activity. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:823–833. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Moroni M, et al. The life span determinant p66Shc localizes to mitochondria where it associates with mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 and regulates trans-membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25689–25695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, et al. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 2005;122:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, et al. Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science. 2007;315:659–663. doi: 10.1126/science.1135380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kudo N, Barr AJ, Barr RL, et al. High rates of fatty acid oxidation during reperfusion of ischemic hearts are associated with a decrease in malonyl-CoA levels due to an increase in 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17513–21750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell RR, 3rd, Bergeron R, Shulman GI, et al. Translocation of myocardial GLUT-4 and increased glucose uptake through activation of AMPK by AICAR. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H643–649. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marsin AS, Bertrand L, Rider MH, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of heart PFK-2 by AMPK has a role in the stimulation of glycolysis during ischaemia. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kantor PF, Lucien A, Kozak R, et al. The antianginal drug trimetazidine shifts cardiac energy metabolism from fatty acid oxidation to glucose oxidation by inhibiting mitochondrial long-chain 3-ketoacyl coenzyme A thiolase. Circ Res. 2000;86:580–588. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCormack JG, Barr RL, Wolff AA, et al. Ranolazine stimulates glucose oxidation in normoxic, ischemic, and reperfused ischemic rat hearts. Circulation. 1996;93:135–142. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.