Abstract

Background

In human adolescents, heavy drinking is often predicted by high sociability in males and high social anxiety in females. This study assessed the impact of baseline levels of social activity and social anxiety-like behavior in group-housed adolescent and adult male and female Sprague-Dawley rats on ethanol intake when drinking alone or in a social group.

Methods

Social activity and anxiety-like behavior initially were assessed in a modified social interaction test, followed by six drinking sessions that occurred every other day in animals given ad libitum food and water. Sessions consisted of 30-min access to 10% ethanol in a “supersac” (3% sucrose + 0.1% saccharin) solution given alone as well as in groups of five same-sex littermates, with order of the alternating session types counterbalanced across animals.

Results

Adolescent males and adults of both sexes overall consumed more ethanol under social than alone circumstances, whereas adolescent females ingested more ethanol when alone. Highly socially active adolescent males demonstrated elevated levels of ethanol intake relative to their low and medium socially active counterparts when drinking in groups, but not when tested alone. Adolescent females with high levels of social anxiety-like behavior demonstrated the highest ethanol intake under social, but not alone circumstances. Among adults, baseline levels of social anxiety-like behavior did not contribute to individual differences in ethanol intake in either sex.

Conclusions

The results clearly demonstrate that in adolescent rats, but not their adult counterparts, responsiveness to a social peer predicts ethanol intake in a social setting – circumstances under which drinking typically occurs in human adolescents. High levels of social activity in males and high levels of social anxiety-like behavior in females were associated with elevated social drinking, suggesting that males ingest ethanol for its socially enhancing properties, whereas females ingest ethanol for its socially anxiolytic effects.

Keywords: ethanol intake, social drinking paradigm, social activity and social anxiety-like behavior, sex differences, adolescence

Alcohol is a widely used substance by American adolescents (Johnston et al., 2013). A critical question regarding adolescent use of alcohol is why do young people drink and sometimes drink excessively? The impact of social context on adolescent drinking is viewed as particularly important (Read et al., 2003), with young individuals typically using alcohol in social situations (Kuntsche et al., 2005). Analysis of drinking motives and personality factors revealed two distinct types of adolescents that engage in heavy drinking (Ham and Hope, 2003; Kuntsche et al., 2006): those that drink to enhance positive emotions, and those that drink to cope. Adolescent males who demonstrate high sociability, impulsivity, and high levels of novelty seeking report enhancement motives more frequently than adolescent females (Cooper, 1994). Adolescent females who show high levels of anxiety, especially in social situations, report drinking for coping reasons (i.e., drinking to avoid negative affective states) more frequently than males (Comeau et al., 2001).

One limitation of the human data, however, is the frequent use of single session, self-report questionnaires, thereby limiting causal interpretation of the results. Empirical studies of underage drinking are also limited by ethical considerations that constrain administration of alcohol to adolescents. Similarities found between adolescent humans and those of other mammalian species in developmentally-related neural, hormonal and behavioral alterations provide reasonable justification for the use of animal models of adolescent alcohol consumption (Spear, 2000, 2011). In humans, adolescence is often thought to subsume the second decade of life, with a late adolescence / emerging adulthood period extending into the mid-late twenties (Arnett, 2000). In rats, a conservative age range during which adolescent-characteristic behavioral and neural features are evident in males and females is the range between postnatal days (P) 28 and P42 (Spear, 2000), with a late adolescence / emerging adulthood period extending from P42 – P55 or so (Schneider, 2013; Vetter-O’Hagen and Spear, 2012).

High levels of ethanol consumption are evident not only in human adolescents but in adolescents of other mammalian species, with for instance adolescent rats ingesting more ethanol relative to their body weights than do adults (Doremus et al., 2005; Hargreaves et al., 2011; Schramm-Sapyta et al., 2013; Vetter-O’Hagen et al., 2009). The vast majority of animal models of ethanol intake have tested animals alone (see Crabbe et al., 2011 for a review). Assessment of drinking under social circumstances, however, seems of considerable importance, given the prominent influence of the social environment on ethanol intake (see Anacker & Ryabinin, 2010).

Sensitivity to ethanol and other drugs may be also affected by social circumstances. For example, exposure to a social peer during intoxication modified responsiveness to aversive properties of ethanol in adolescents, but not in adults. Adolescent males housed alone during the intoxication period showed conditioned taste aversion (CTA) at 2.0 g/kg ethanol, whereas the presence of a peer attenuated expression of CTA at this ethanol dose (Vetter-O’Hagen et al., 2009). While decreasing responsiveness to the aversive properties of ethanol, social interactions have been reported to enhance the rewarding value of cocaine (Thiel et al., 2008) or nicotine (Thiel et al., 2009) in adolescent rats tested in a conditioned place preference paradigm.

Given the importance of social interactions in ethanol drinking, Experiment 1 assessed the impact of drinking context (alone or in a social group) in group-housed adolescent and adult male and female rats using a within-subject design. Levels of social activity were also assessed to investigate whether high baseline sociability serves as a major contributor to elevated levels of social ethanol intake in adolescent males, whereas elevated levels of anxiety-like behavior under social circumstances contribute to high intake in a social context in adolescent females. Since a sweetened ethanol solution was used in Experiment 1, Experiment 2 was conducted to determine whether social contributors were specific to ethanol by assessing intake of the sweetened solution alone.

General Methods

Subjects

Adolescent and adult male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (n=352) bred and reared in our colony at Binghamton University were used. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled (22°C) vivarium maintained on a 14-/10-hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 hr) with ad libitum access to food (Purina Rat Chow, Lowell, MA) and water. Litters were culled to 10 (5 male and 5 female) pups whenever feasible on postnatal day (P) 1 and housed with their mothers. Pups were weaned on P21 and placed together with their same-sex littermates. In all respects, maintenance and treatment of the animals were in accord with guidelines for animal care established by the National Institutes of Health, using protocols approved by the Binghamton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Procedure

Social interaction testing was initiated on P30 or P70. Starting at P36 for adolescents and P76 for adults, intake of the sweetened ethanol solution was then assessed every other day over six 30-min drinking sessions (3 sessions of social drinking alternating with 3 sessions of drinking alone) in Experiment 1. In Experiment 2, only adolescent animals were tested using procedures similar to those of Experiment 1 except that intake of a sweetened solution used as the vehicle for ethanol was assessed.

Modified Social Interaction Test

On test day, each experimental animal was placed individually for 30 min in a two-compartment testing apparatus (overall dimensions: 30 × 20 × 20 cm for adolescents and 45 × 30 × 20 cm for adults) with an aperture (7 × 5 cm for adolescents and 9 × 7 cm for adults) connecting the two sides. A peer of the same age and sex was then introduced for a 10-min test period. Partners were always unfamiliar with both the test apparatus and the experimental animal, and were not socially deprived prior to the test (Varlinskaya and Spear, 2002). Weight differences between test subjects and their partners were minimized and did not exceed 10 g at P30 or 20 g at P70, with test subjects always being heavier than their partners.

The behavior of the animals was video recorded, with real time being directly stamped onto the recording for later scoring (Easy Reader II Recorder; Telcom Research TCG 550, Burlington, Ontario). All testing procedures were conducted between 9:00 and 13:00 hr under dim light (15–20 lx). Behavioral data were scored from the video records by trained observers without knowledge of the experimental condition of any animal. Agreement between observers was in excess of 90% for each measure of social behavior.

Overall social activity was scored as the sum of the frequencies of the following social behaviors: social investigation (sniffing of any part of the body of the partner), contact (crawling over and under the partner and social grooming), and play behavior (pouncing or playful nape attack, chasing, and pinning).

The number of crossovers (movements between compartments) demonstrated by the experimental subject toward the partner and the number of crossovers away from the partner was also determined for each session (Varlinskaya and Spear, 2002). Levels of social anxiety-like behavior were indexed using these data via a coefficient of social preference/avoidance [Coefficient (%) = (crossovers to − crossovers from) / (crossovers to + crossovers from)]. Low social anxiety-like behavior was defined by high positive values of the coefficient, whereas high levels of social anxiety-like behavior were associated with extremely low positive or negative values (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2009; Varlinskaya et al., 2010).

Drinking Procedure

Rats were given access to 10% ethanol in “supersac” solution (3% sucrose + 0.125% saccharin, see Ji et al., 2008) in a novel cage during a 30-min drinking session every other day (six sessions) from P36 to P46 for adolescents and P76–86 for adults (Experiment 1). Only six drinking sessions were employed, given that long-lasting ethanol exposure during adolescence can alter social activity and anxiety-like behavior, at least in male subjects (Varlinskaya et al., 2014), with these alterations markedly complicating assessment of social contributors to ethanol intake. On alternating days for each animal, ethanol access occurred either alone (one bottle of ethanol solution) or in a group of four - five littermates (2 bottles with ethanol), with the order of social/alone drinking sessions counterbalanced within each age/sex group. Animals were not food or water deprived. All social drinking sessions were video recorded, with individual intakes extrapolated from the proportional time spent drinking per individual animal × g ethanol consumed by the group / body weight. Our preliminary study demonstrated a significant correlation between time spent drinking and volume consumed of ethanol solution in individually tested adolescent male (r=0.92, p =0.0007) and female (r=0.90, p=0.0003) rats as well as their adult counterparts (r=0.92, p=0.0001, r=0.97, p<0.0001, respectively), therefore, confirming that time spent drinking is a reliable measure for assessment of ethanol intake. Experiment 2 was conducted similarly, with adolescent animals only being tested with ”supersac” solution.

Blood Ethanol Determination

Trunk blood samples were collected immediately after the last drinking session. Samples were assessed for blood ethanol concentration (BEC) via headspace gas chromatography using a Hewlett Packard (HP) 5890 series II Gas Chromatograph (Wilmington, DE).

Data Analyses

In Experiment 1, age and sex differences in ethanol intake under social or alone circumstances averaged across the three drinking sessions were analyzed using a 2 (age) × 2 (sex) × 2 (drinking context) analysis of variance (ANOVA), with context treated as a repeated measure. In Experiment 2, sex differences in ethanol intake under social or alone circumstances in adolescent rats were assessed using a 2 (sex) × 2 (drinking context) ANOVA, with context again treated as a repeated measure. Ethanol intake and BECc assessed on the last test day in Experiment 1 were analyzed using separate 2 (sex) × 2 (age) × 2 (drinking context) ANOVAs, with context in these analyses being a between-subject factor. For determination of animals with Low, Medium, and High social activity or social anxiety-like behavior, a tertile split was used within each age/sex condition (n=10 animals/group, Experiment 1). Similarly, In Experiment 2, adolescent males and females were divided into the groups with Low (n=9 rats/group), Medium (n=10/group), and High (n=9/group) social activity or social anxiety-like behavior. The influence of individual differences in baseline levels of social activity or social anxiety-like behavior on subsequent ethanol intake (or “supersac” intake) under social or alone circumstances were analyzed for each age in Experiment 1 and for adolescents only in Experiment 2, using separate 3 (level of social activity or social anxiety-like behavior: Low, Medium, High) × 2 (sex) × 2 (drinking context) mix-factor ANOVAs, with drinking context treated as a repeated measure. In order to avoid inflating the possibility of type II errors on tests with at least 3 factors (Carmer & Swanson, 1973), Fisher’s planned pair-wise comparisons were used to explore significant effects and interactions.

On the last drinking day, all animals were video recorded, and time spent drinking was scored for each individual experimental subject. Then, correlations between time spent drinking and BECs were calculated for each age/sex/drinking context condition, with significance of these correlations assessed using Z test.

Results

Experiment 1. Ethanol intake when alone or under social circumstances

Ethanol intake averaged across social and alone drinking sessions (Fig.1)

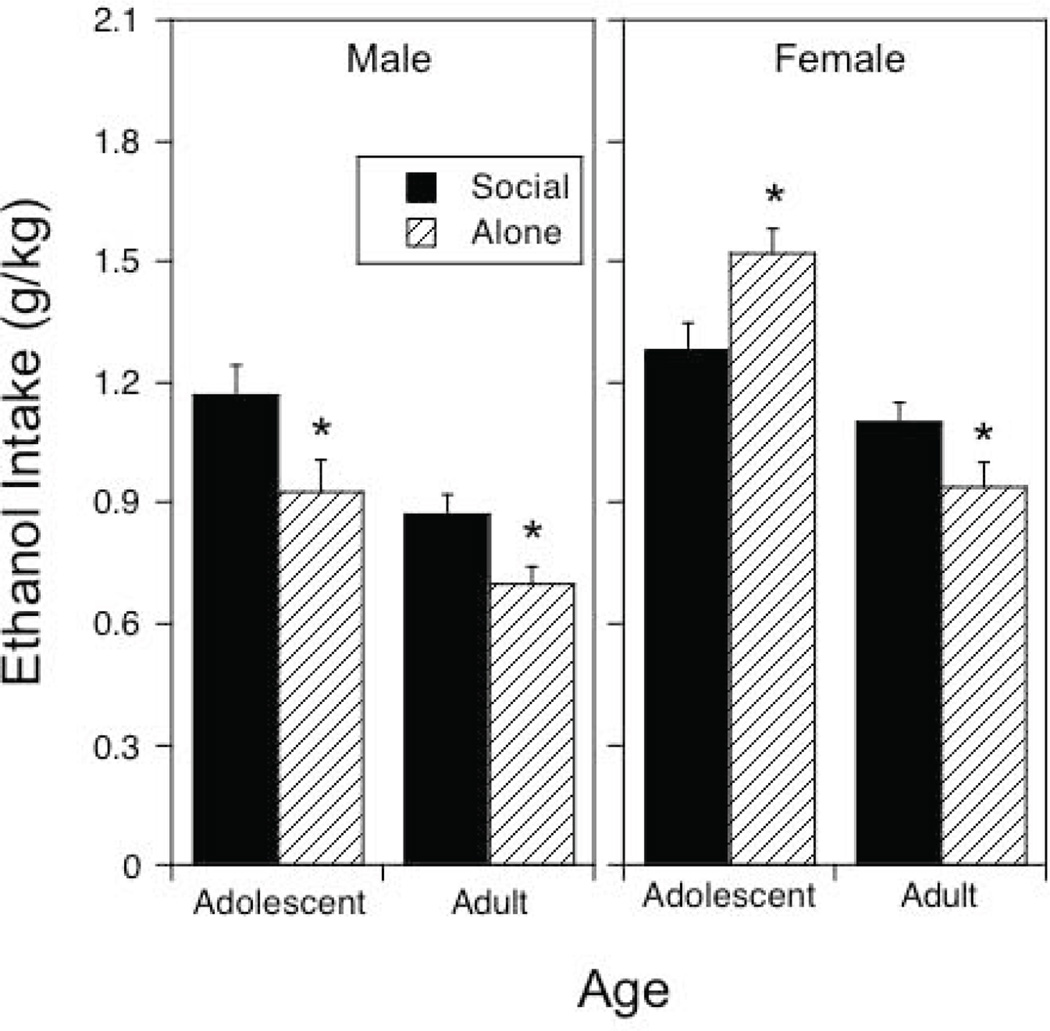

Figure 1.

Ethanol intake under social or alone circumstances in adolescent and adult males and females averaged across social and alone drinking sessions.

Asterisks (*) indicate significant (p < .05) changes in ethanol intake under alone circumstances relative to social intake.

Intake was greater in adolescents than in adults, F(1, 116) = 36.92, p < .0001, and females demonstrated higher intake than males regardless of age, F(1, 116) = 31.74, p < .0001. Context significantly interacted with both of these variables, F(1, 116) = 14.20, p < .001. Ethanol intake was significantly higher in the social context than when drinking alone in males of both ages and in adult females, whereas adolescent females drank notably more ethanol when alone than in a social context.

Last drinking session: intake and BEC (Table 1)

Table 1.

Experiment 1. Ethanol intake and BECs from the last drinking session among adolescent and adult males and females drinking socially or alone.

| Sex | Age | Context | Ethanol intake (g/kg) |

BEC (mg/dl) |

Correlation between time spent drinking and BEC |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | |||||

| Male | Adolescent | social | 1.23 ± 0.14* | 19.2 ± 6.5* | 0.82 | 0.0006 |

| alone | 0.84 ± 0.10 | 8.2 ± 2.3 | 0.80 | 0.0007 | ||

| Adult | social | 0.66 ± 0.09 | 32.6 ± 7.0 | 0.83 | 0.0005 | |

| alone | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 41.1 ± 7.3 | 0.81 | 0.0001 | ||

| Female | Adolescent | social | 1.24 ± 0.14* | 21.5 ± 7.0* | 0.88 | 0.0002 |

| alone | 1.74 ± 0.11 | 45.6 ± 6.5 | 0.86 | 0.0003 | ||

| Adult | social | 1.26 ± 0.19 | 69.6 ± 8.6 | 0.92 | 0.0001 | |

| alone | 0.92 ± 0.13 | 50.0 ± 10.1 | 0.91 | 0.0001 | ||

Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between social and alone drinking circumstances (p < .05) within each age/sex group.

Ethanol intake and BECs from the last day of testing in Experiment 1 were assessed across age and sex among animals drinking alone versus socially on the last test day (i.e., with drinking context serving as a between-subject factor). Pronounced age, F(1, 112) = 16.0, p < .0001, and sex differences, F(1, 112) = 21.04, p < .0001, emerged, with adolescents showing higher intake than adults and females consuming more ethanol than males. Similar to intake data averaged across social and alone drinking sessions (see Figure 1), adolescent males drinking in groups consumed more ethanol than their counterparts drinking alone, whereas adolescent females drank more ethanol while alone relative to those tested in social groups [age × sex × context interaction, F(1,112) = 14.34, p < .001]. In adults, however, ethanol intake on the last test day did not differ as a function of drinking context.

Although adolescents ingested more ethanol than adults, they demonstrated lower BECs, F(1, 112) = 19.4, p < .0001, whereas females showed higher BECs than males regardless of age, F(1, 112) = 14.64, p < .001. Most importantly, BECs differed as a function of drinking context in adolescents only [age × sex × context interaction, F(1, 112) = 7.97, p < .01]: males drinking in groups showed higher BECs than those drinking alone, whereas females drinking alone achieved substantially higher BECs than those drinking in groups. Similar to intake, there was no effect of drinking context on BECs of adult males and females.

Statistically significant correlations between time spent drinking and BECs were evident for all experimental conditions, with animals of the same age and sex demonstrating comparable correlation values when drinking socially or alone (see Table 1), suggesting that time spent drinking is a reliable measure for the assessment of ethanol intake.

Social activity and ethanol intake (Table 2, Figure 2)

Table 2.

Experiment 1. Levels of social activity in adolescent and adult males and females.

| Social Activity Level |

Overall Social Activity Frequency / 10 min (mean ± S.E.M.) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Adolescent | Adult | Adolescent | Adult | |

| Low | 107.6 ± 8.6 | 98.5 ± 3.8 | 117.6 ± 5.5 | 81.0 ± 5.5 |

| Medium | 165.0 ± 3.1 | 127.9 ± 3.6 | 156.1 ± 3.5 | 116.6 ± 1.7 |

| High | 207.6 ± 6.3 | 162.2 ± 11.9 | 193.9 ± 12.4 | 138.8 ± 10.2 |

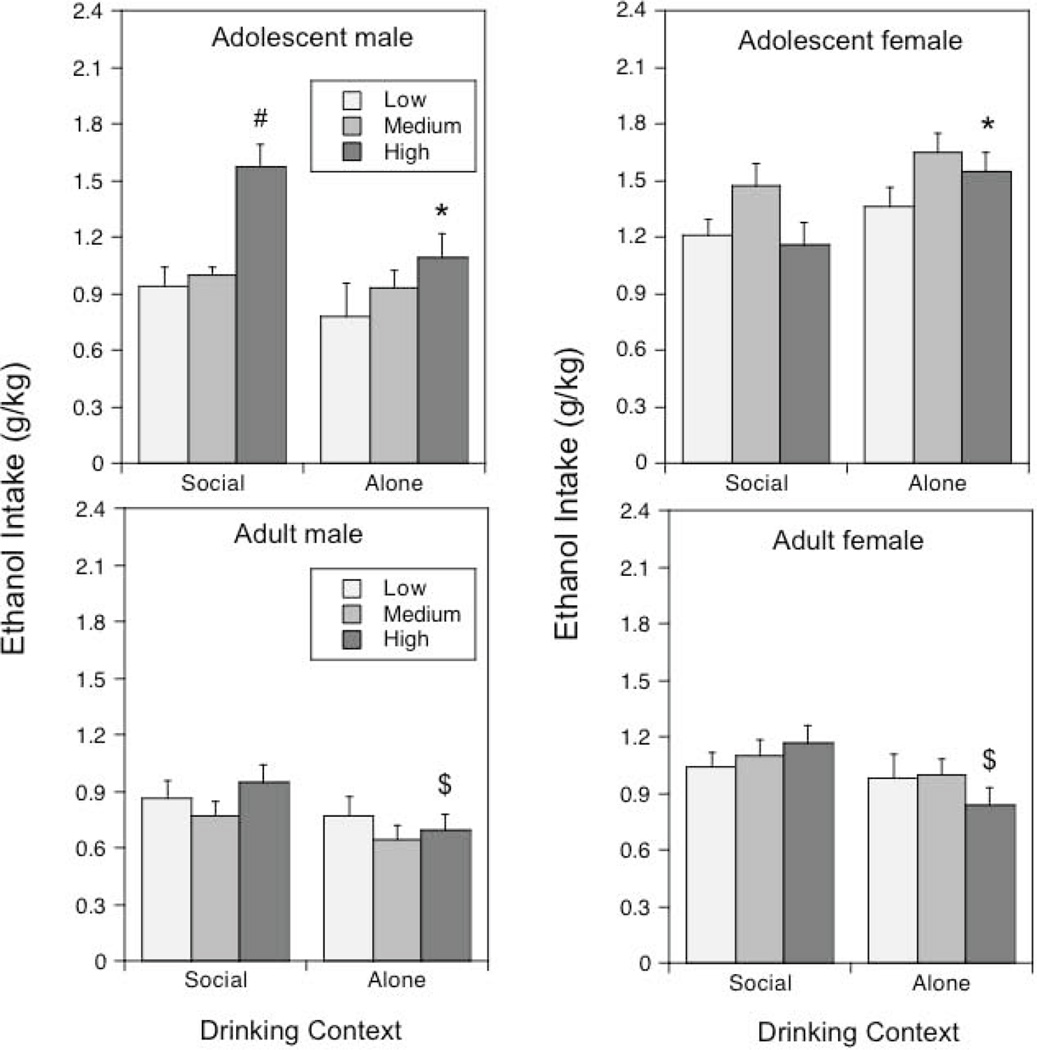

Figure 2.

Ethanol intake under social or alone circumstances in adolescent and adult males and females: Impact of baseline levels of social activity.

Asterisks (*) indicate significant (p < .05) changes in ethanol intake under alone circumstances relative to social intake within the same age/sex condition; the # sign reflects significantly (p < .05) greater intake in High relative to Low and Medium socially active adolescent males tested under social circumstances, whereas the $ sign indicates significant (p <.05) differences between alone and social test circumstances, with data collapsed across sex.

When overall social activity (Table 2) was used to divide animals into tertiles, and the data analyzed by a 2 age × 2 sex × 3 activity level ANOVA, overall social activity was found to be substantially higher in adolescents than adults, F(1, 108) = 83.65, p < .0001, with the most pronounced age differences evident in Medium and High socially active animals [age × activity level interaction, F(2, 108) = 4.33, p < .05]. Females were less socially active than males, F(1, 108) = 7.85, p < .01.

In adolescents, level of social activity was associated with ethanol intake under social and alone circumstances in a sex-dependent fashion [level of social activity × sex × context interaction, F(2, 54) = 4.17, p < .05]. High socially active adolescent males demonstrated elevated levels of ethanol intake relative to their Low and Medium active counterparts when drinking in groups and drastically decreased intake when drinking alone (Fig.2, left). Although ethanol intake was similar under social and alone conditions among Low and Medium socially active adolescent females, High socially active adolescent females drank significantly more when alone than under social circumstances.

Adult males and females with High levels of social activity drank significantly less when tested alone than when tested socially, whereas ethanol intake did not differ as a function of drinking context in Low and Medium socially active adults [level of social activity × context interaction, F(2, 54) = 3.29, p < .05].

Social anxiety-like behavior and ethanol intake (Table 3, Figure 3)

Table 3.

Experiment 1. Levels of social anxiety-like behavior in adolescent and adult males and females.

| Social Anxiety Level |

Social Preference / Avoidance Coefficient (mean ± S.E.M.) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Adolescent | Adult | Adolescent | Adult | |

| Low | 47.8 ± 3.4 | 41.0 ± 3.2 | 42.9 ± 3.1 | 34.7 ± 2.1 |

| Medium | 24.3 ± 2.0 | 17.9 ± 2.7 | 20.4 ± 1.3 | 15.4 ± 1.1 |

| High | −2.7 ± 3.5 | −10.9 ± 4.2 | 4.4 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 1.5 |

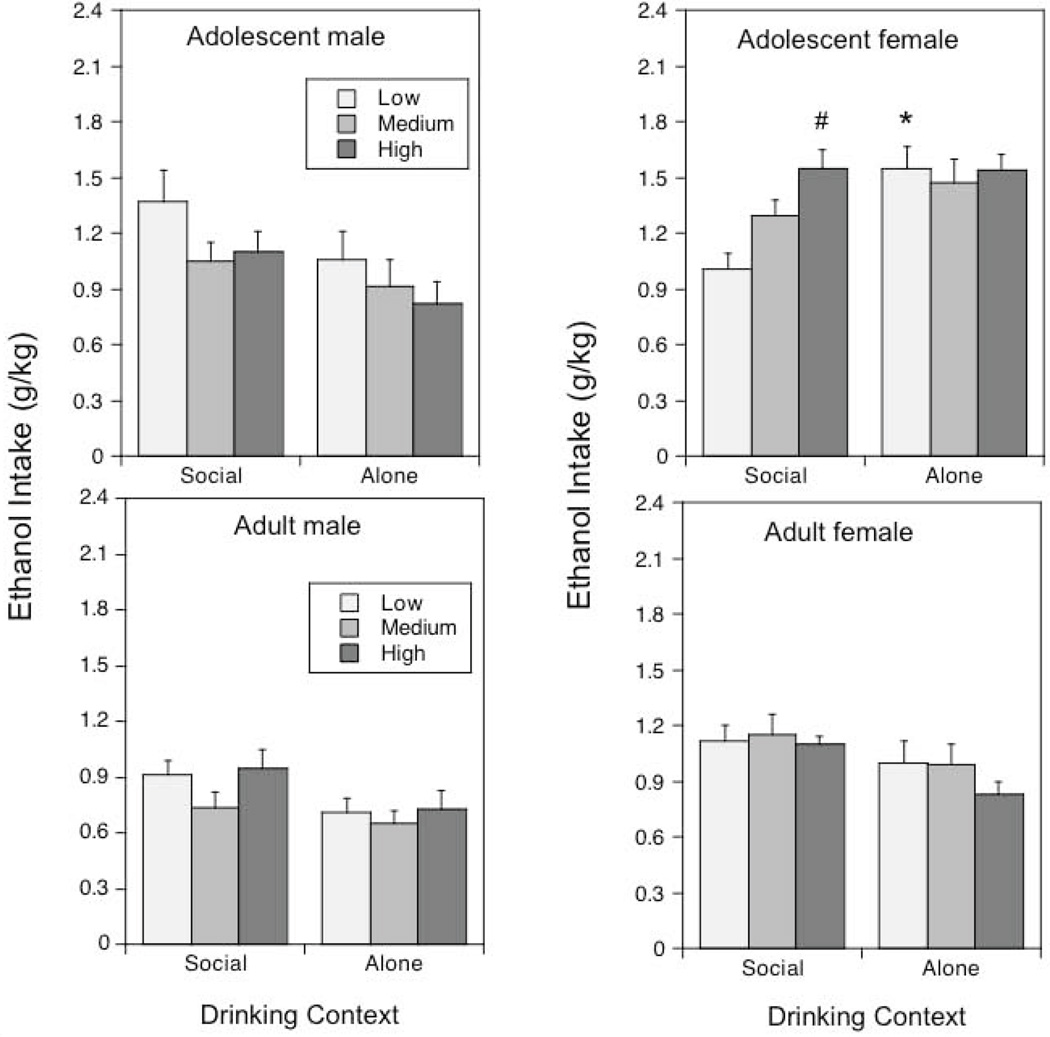

Figure 3.

Ethanol intake under social or alone circumstances in adolescent and adult males and females: Impact of baseline levels of social anxiety-like behavior.

Asterisks (*) indicate significant (p < .05) changes in ethanol intake under alone circumstances relative to social intake within the same age/sex condition; the # sign reflects significantly (p < .05) greater intake in High relative to Low socially anxious adolescent females tested under social circumstances.

When the coefficient of social preference (an index of anxiety-like behavior) was used to divide animals into tertiles and analyzed, the coefficient was found to be significantly higher in adolescents than in adults, F(1, 108) = 20.64, p < .0001 (see Table 3). The coefficient did not differ as a function of sex in animals with Low and Medium levels of social anxiety-like behavior, whereas sex differences became evident in rats with High social anxiety-like behavior, with females still showing social preference indexed via positive, albeit low values of the coefficient, and males demonstrating social avoidance [sex × anxiety-like behavior level interaction, F(2, 108), p < .005].

In adolescent females, but not adolescent males, drinking context influenced the impact of levels of social anxiety-like behavior on ethanol intake [level of social anxiety-like behavior × sex × context interaction, F(2, 54) = 3.82, p < .05]. Adolescent females exhibiting High levels of social anxiety-like behavior consumed more ethanol under social circumstances than those with Low levels, whereas the intake of the Low group of females was notably increased when they were tested alone. Indeed, under alone test circumstances ethanol intake did not differ among adolescent females with Low, Medium and High levels of anxiety-like behavior. In adult males and females, levels of social anxiety-like behavior were not associated with ethanol intake.

Experiment 2. “Supersac” intake when alone or under social circumstances

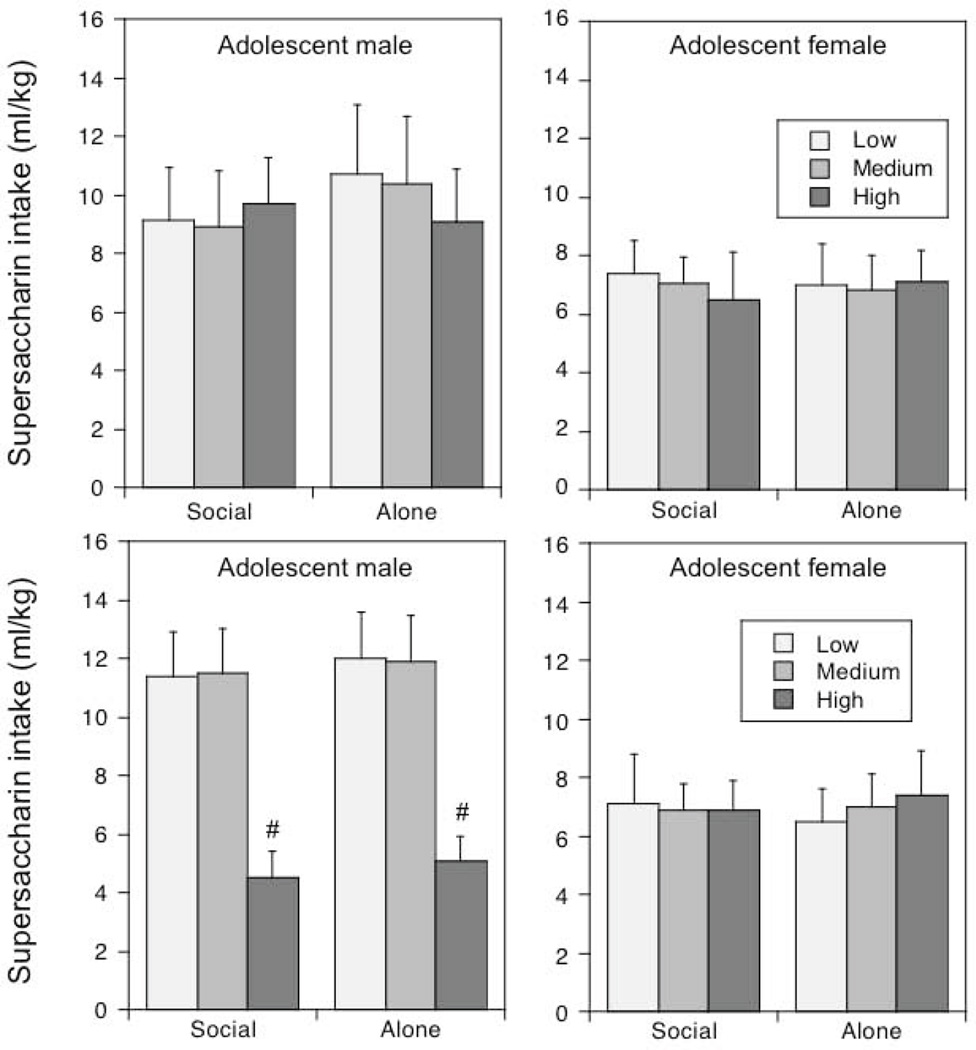

“Supersac” intake (Figure 4)

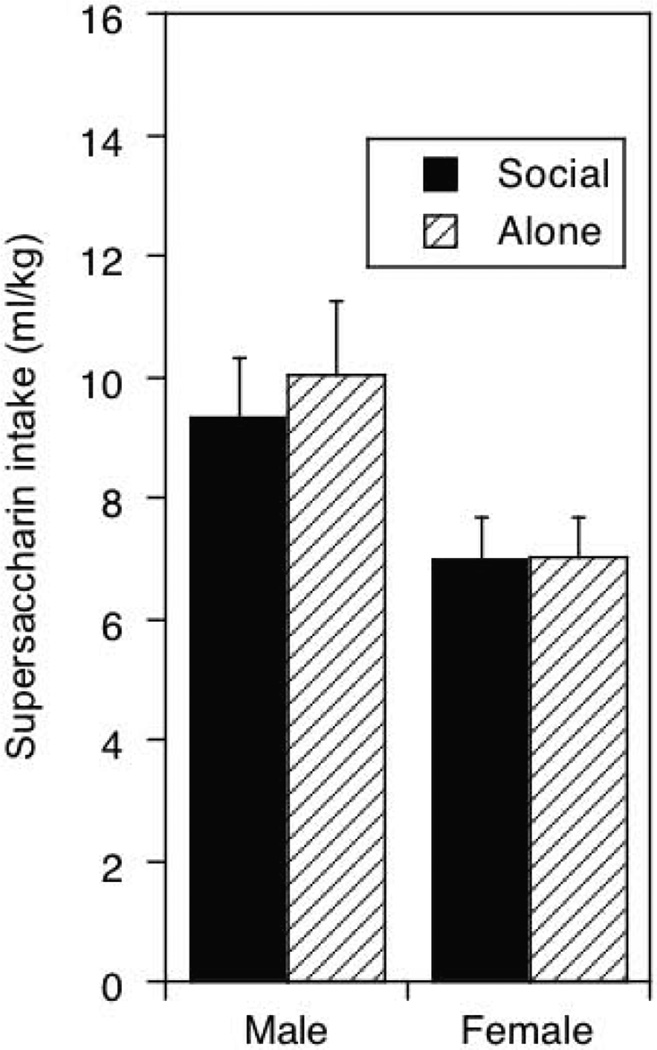

Figure 4.

“Supersac” intake under social or alone circumstances in adolescent and males and females averaged across social and alone drinking sessions.

“Supersac” intake measured in terms of ml/kg was significantly higher in adolescent males than adolescent females under both test circumstances, F (1, 54) = 4.98, p < .05. Social versus alone test circumstances played no role in “supersac” intake.

Social activity, social anxiety-like behavior and “supersac” intake (Table 4, Figure 5)

Table 4.

Experiment 2: Levels of social activity or social anxiety-like behavior in adolescent and adult males and females.

| Level of Activity or Anxiety-like behavior |

Overall Social Activity Frequency / 10 min (mean ± S.E.M.) |

Social Preference / Avoidance Coefficient (mean ± S.E.M.) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Low | 115.1 ± 10.2 | 101.6 ± 5.0 | 42.3 ± 2.6 | 42.8 ± 5.5 |

| Medium | 160.0 ± 4.8 | 141.7 ± 6.7 | 23.8 ± 1.4 | 27.0 ± 1.7 |

| High | 198.3 ± 9.4 | 177.0 ± 5.8 | 1.2 ± 5.6 | 1.8 ± 3.7 |

Figure 5.

“Supersac” intake under social or alone circumstances in adolescent males and females: Impact of baseline levels of social activity (top) or social anxiety-like behavior (bottom).

The # sign reflects significantly (p < .05) lower intake in adolescent males with High social anxiety-like behavior relative to those with Low and Medium.

When overall social activity was used to divide animals into tertiles, and the data analyzed by a 2 sex × 3 activity level ANOVA, overall social activity was found to be significantly higher in adolescent males than adolescent females, F(1, 50) = 9.24, p < .01. The coefficient of social preference did not differ as a function of sex.

There were no effects of levels of social activity on “supersac” intake either under social or alone circumstances. However, level of social anxiety-like behavior was associated with “supersac” intake in a sex-dependent fashion [level of social anxiety-like behavior × sex interaction, F(2, 50) = 5.45, p < .01]. Adolescent males with High levels of social anxiety-like behavior demonstrated significantly lower “supersac” intake relative to their counterparts with Medium and Low levels regardless of test circumstances. In adolescent females, levels of social anxiety-like behavior did not contribute to individual differences in “supersac” intake.

Discussion

Age and sex differences in ethanol intake have been reported previously under social and alone test circumstances, with adolescents showing higher intake than adults (Doremus et al., 2005; Hargreaves et al., 2010; Schramm-Sapyta et al., 2013; Vetter-O’Hagen et al., 2009) and females drinking more than males (Lancaster et al., 1996; Piano et al., 2005; Vetter-O’Hagen et al., 2009). In the present study, these levels of intake, however, were found to be influenced by the drinking context in which ethanol access occurred. When intake under social and alone conditions was averaged across sessions and the drinking context was treated as a repeated measure, adolescent males, adult males, and adult females consumed more ethanol when drinking in groups than when drinking alone. In contrast, ethanol intake of adolescent females was significantly higher when drinking alone than socially. This impact of test circumstances on ethanol intake during adolescence was not related to the sweet taste of ethanol solution, since intake of the sweet solution alone did not differ as a function of test circumstances in either adolescent males or females. In contrast to sex differences in ethanol intake, with adolescent females ingesting more ethanol than adolescent males, intake of “supersac” was significantly higher in males than in females during adolescence.

The impact of drinking circumstances on ethanol intake in adults was not as robust as in adolescents, since no differences were evident on the last test day between adults drinking in groups or alone. Similarly, only in adolescents, BECs differed between animals drinking socially and those drinking alone, with adolescent males demonstrating higher BECs under social than alone drinking circumstances and adolescent females drinking alone achieving greater BECs than those drinking in groups. Although ingesting more ethanol than adults, adolescents demonstrated lower BECs. These discrepancies between intake and BECs were reported previously (e.g., Broadwater et al., 2011). Taken together, these results suggest possible age-associated differences in post-ingestion ethanol pharmacokinetics, including its absorption and elimination.

Adolescent males ingested more ethanol under social than alone test circumstances. Studies using rats have previously shown that interactions with peers provide a significant source of positive experiences (Trezza et al., 2011) and are seemingly more rewarding for adolescents than for their more mature counterparts (Douglas et al., 2004; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2009). This social context may make ethanol more appealing for adolescent males by attenuating the aversive effects of ethanol (e.g., Vetter-O’Hagen et al., 2009), while also perhaps enhancing its positively reinforcing effects. Indeed, although not yet examined with ethanol, social context-related enhancement of drug reward during adolescence has been observed in adolescent male rats with nicotine (Thiel et al., 2009) and cocaine (Thiel et al., 2008). Not only social context of drinking, but deprivation from social interactions during adolescence can elevate ethanol intake in males as well. When male rats underwent a stressful procedure of long-term social deprivation during the adolescent period, they demonstrate a number of neural and behavioral alterations (Miyazaki et al., 2012; Pascual and Bustamante, 2013; Wall et al., 2012; Whitaker et al., 2013), and increased ethanol self-administration is one of these alterations (Chappell et al., 2013; Ehlers et al., 2007; Juarez and Vazquez-Cortes, 2003; Schenk et al., 1990). Therefore, an opportunity to interact with peers while drinking enhances ethanol intake in adolescent males under normal circumstances, whereas long-term deprivation of adolescent male rats from these normal social interactions increases ethanol intake under stressful social isolation circumstances.

The impact of drinking context on ethanol intake was evident predominantly in high socially active animals. Greater intake in a social context than when alone was seen only in males and adult females that demonstrated the highest levels of social activity. This social context-dependent ethanol intake was most pronounced in high socially active adolescent males, with these animals showing a 31% decrease in ethanol intake when drinking alone than when drinking socially. Social intake in this group of adolescent males was almost two times higher than that of medium and low socially active adolescent males. The observed impact of drinking context and baseline levels of social activity were evident in adolescent males exposed to sweetened ethanol. However, in adolescent males, intake of the sweet solution was similar under social and alone drinking circumstances, with no differences evident among adolescent males with Low, Medium and High levels of social activity. Taken together, these findings suggest that high baseline sociability may serve as a major contributor to initiation of heavy social drinking in adolescent male rats, similar to their human counterparts (Ham & Hope, 2003; Kuntsche et al., 2006), with this contributor being to a large extent selective for ethanol intake. It is tempting to speculate that these socially active adolescent males may find ethanol especially appealing due to its socially facilitating effects – effects that can be obviously experienced only under social drinking circumstances. This possibility has yet to be systematically tested.

Ethanol intake of adolescent females, however, was significantly higher when drinking alone than socially. This increase in ethanol intake when alone may be associated with enhanced sensitivity of adolescent females, especially high socially active animals, to the stressfulness of social deprivation, with adolescent females that were socially deprived during the intake test perhaps consuming more ethanol for its anxiolytic effects. Indeed, it was only in adolescent females that baseline levels of social anxiety-like behavior were associated with ethanol intake. Specifically, adolescent females with High levels of social anxiety-like behavior demonstrated the highest ethanol intake under social circumstances, whereas adolescent females with the lowest levels of social anxiety demonstrated the lowest social intake but drastically increased their intake when drinking alone. However, levels of social anxiety-like behavior did not contribute to “supersac” intake in adolescent females, suggesting that social anxiety-like behavior may be viewed as a rather specific predictor of elevated social drinking in females during adolescence. These findings suggest that adolescent females may ingest ethanol for its anxiolytic effects, with these effects playing a substantial role for socially anxious females under social circumstances and for females that are not socially anxious when they are socially deprived. The hypothesis that adolescent females with high levels of social anxiety-like behavior are more sensitive to the socially anxiolytic effects of ethanol than adolescent and adult males as well as adult females still remains to be investigated.

The relationship between different forms of anxiety disorders and alcohol consumption in humans during adolescence and adulthood is complex and still not well understood. Although anxiolytic effects of alcohol have sometimes been suggested to contribute to elevated levels of ethanol intake during adolescence in human studies (Carrigan and Randall, 2003; Kuntsche et al., 2005), it has been reported that anxious adults do not choose alcohol more often then non-anxious controls under acute test circumstances (Chutuape and deWit, 1995). The results of animal studies are inconsistent as well. Some studies have shown a strong relationship between anxiety-like behavior and ethanol intake in male rats and mice (Bahi, 2013; Chappell et al., 2013; Kallupi et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2011) following experimental manipulations that enhance anxiety-like behavior (i.e., ethanol dependence, social isolation, stress). Positive correlations between baseline levels of anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze (EPM) and ethanol intake were found for Wistar rats (Spanagel et al., 1995).. A similar relationship between anxiety-like behavior on the EPM and ethanol intake was reported for male Tuck-Ordinary mice (Bahi, 2013). In contrast, Langen and Fink (2004), using males from three strains of rats with different anxiety-like behavior on the EPM, failed to find positive correlations between levels of anxiety-like behavior and ethanol intake. When ethanol self-administration was assessed in rats selectively bred for differences in anxiety-like behavior on the EPM – i.e., the high anxiety-related behavior (HAB) and low anxiety-related behavior (LAB) lines – female LAB rats ingested more ethanol that their HAB counterparts during the initiation phase, with a similar, although not statistically significant trend seen in males (Henniger et al., 2002). Reminiscent of these latter studies, we also failed to find any differences between socially anxious and non-anxious adults and adolescent males in ethanol intake when drinking under social or alone circumstances. Although ethanol intake was comparable in adolescent males with different baseline levels of social anxiety-like, “supersac” intake was substantially lower in adolescent males with High levels of social anxiety-like behavior relative to those with Medium and Low levels. Decreased intake of a sweet solution may be viewed as a sign of anhedonia in these adolescent males (Anisman and Matheson, 2005).

In summary, the results of the present study clearly demonstrate that in adolescent rats, but not adults, responsiveness to a peer predicts ethanol intake under social circumstances – circumstances that are most common for adolescent drinking in humans (Read et al., 2003). High levels of social activity are associated with high ethanol intake in adolescent males when drinking in groups, but not when drinking alone, suggesting that these males ingest ethanol for its socially enhancing properties. High levels of social anxiety-like behavior are associated with high levels of social drinking in adolescent females, suggesting that these females ingest ethanol for its socially anxiolytic effects. To the extent that these experimental findings are applicable to humans, drinking under social circumstances in adolescent males with high baseline levels of social activity as well as in adolescent females with high baseline levels of social anxiety may provide useful sex-dependent animal models of adolescent heavy drinking. In future, these models will allow systematic assessment of sex-specific mechanisms involved in heavy social drinking during adolescence, providing a background for creating gender-specific prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper was supported by NIH grant U01 AA019972 – NADIA Project.

References

- Anacker AM, Ryabinin AE. Biological contribution to social influences on alcohol drinking: evidence from animal models. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(2):473–493. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker AM, Loftis JM, Kaur S, Ryabinin AE. Prairie voles as a novel model of socially facilitated excessive drinking. Addict Biol. 2011;16(1):92–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Matheson K. Stress, depression, and anhedonia: caveats concerning animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:525–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi A. Individual differences in elevated plus-maze exploration predicted higher ethanol consumption and preference in outbred mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;105:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadwater M, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Chronic intermittent ethanol exposure in early adolescent and adult male rats: effects on tolerance, social behavior, and ethanol intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1392–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmer SG, Swanson MR. An evaluation of ten pairwise multiple comparison procedures by Monte Carlo methods. J Amer Srtat Assoc. 1973;68:66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan MH, Randall CL. Self-medication in social phobia: a review of the alcohol literature. Addict Behav. 2003;28(2):269–284. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell AM, Carter E, McCool BA, Weiner JL. Adolescent rearing conditions influence the relationship between initial anxiety-like behavior and ethanol drinking in male Long Evans rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(Suppl 1):E394–E403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MA, de Wit H. Preferences for ethanol and diazepam in anxious individuals: an evaluation of the self-medication hypothesis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;121(1):91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02245595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau N, Stewart SH, Loba P. The relations of trait anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and sensation seeking to adolescents' motivations for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Addict Behav. 2001;26(6):803–825. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Physiological Assessment. 1994;6:17–128. [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Harris RA, Koob GF. Preclinical studies of alcohol binge drinking. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1216:24–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus TL, Brunell SC, Rajendran P, Spear LP. Factors influencing elevated ethanol consumption in adolescent relative to adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(10):1796–1808. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183007.65998.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Social and non-social anxiety in adolescent and adult rats after repeated restraint. Physiol Behav. 2009;97(3–4):484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Motivational systems in adolescence: possible implications for age differences in substance abuse and other risk-taking behaviors. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas LA, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Rewarding properties of social interactions in adolescent and adult male and female rats: impact of social versus isolate housing of subjects and partners. Dev Psychobiol. 2004;45(3):153–162. doi: 10.1002/dev.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Walker BM, Pian JP, Roth JL, Slawecki CJ. Increased alcohol drinking in isolate-housed alcohol-preferring rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(1):111–119. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23(5):719–759. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves GA, Wang EY, Lawrence AJ, McGregor IS. Beer promotes high levels of alcohol intake in adolescent and adult alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol. 2011;45(5):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henniger MS, Spanagel R, Wigger A, Landgraf R, Holter SM. Alcohol self-administration in two rat lines selectively bred for extremes in anxiety-related behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(6):729–736. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Gilpin NW, Richardson HN, Rivier CL, Koob GF. Effects of naltrexone, duloxetine, and a corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 receptor antagonist on binge-like alcohol drinking in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f3cf70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Institute for Social Research. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan; 2013. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Juarez J, Vazquez-Cortes C. Alcohol intake in social housing and in isolation before puberty and its effects on voluntary alcohol consumption in adulthood. Dev Psychobiol. 2003;43(3):200–207. doi: 10.1002/dev.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallupi M, Vendruscolo LF, Carmichael CY, George O, Koob GF, Gilpin NW. Neuropeptide Y Y2 R blockade in the central amygdala reduces anxiety-like behavior but not alcohol drinking in alcohol-dependent rats. Addict Biol. 2014;19:755–757. doi: 10.1111/adb.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav. 2006;31(10):1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster FE, Brown TD, Coker KL, Elliott JA, Wren SB. Sex differences in alcohol preference and drinking patterns emerge during the early postpubertal period. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(6):1043–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen B, Fink H. Anxiety as a predictor of alcohol preference in rats? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(6):961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Becker HC. Chronic social isolation and chronic variable stress during early development induce later elevated ethanol intake in adult C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol. 2011;45:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki T, Takase K, Nakajima W, Tada H, Ohya D, Sano A, Goto T, Hirase H, Malinow R, Takahashi T. Disrupted cortical function underlies behavior dysfunction due to social isolation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2690–2701. doi: 10.1172/JCI63060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual R, Bustamante C. Early postweaning social isolation but not environmental enrichment modifies vermal Purkinje cell dendritic outgrowth in rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2013;73(3):387–393. doi: 10.55782/ane-2013-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piano MR, Carrigan TM, Schwertz DW. Sex differences in ethanol liquid diet consumption in Sprague-Dawley rats. Alcohol. 2005;35(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(1):13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Gorman K, Amit Z. Age-dependent effects of isolation housing on the self-administration of ethanol in laboratory rats. Alcohol. 1990;7(4):321–326. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Adolescence as a vulnerable period to alter rodent behavior. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354(1):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm-Sapyta NL, Francis R, Macdonald A, Keistler C, O'Neill L, Kuhn CM. Effect of sex on ethanol consumption and conditioned taste aversion in adolescent and adult rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013 Oct 26; doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3319-y. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Montkowski A, Allingham K, Stohr T, Shoaib M, Holsboer F, Landgraf R. Anxiety: a potential predictor of vulnerability to the initiation of ethanol self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;122(4):369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF02246268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(4):417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Adolescent neurobehavioral characteristics, alcohol sensitivities, and intake: Setting the stage for alcohol use disorders? Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5(4):231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Okun AC, Neisewander JL. Social reward-conditioned place preference: a model revealing an interaction between cocaine and social context rewards in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(3):202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Sanabria F, Neisewander JL. Synergistic interaction between nicotine and social rewards in adolescent male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;204(3):391–402. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJ. Evaluating the rewarding nature of social interactions in laboratory animals. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1(4):444–458. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Acute effects of ethanol on social behavior of adolescent and adult rats: role of familiarity of the test situation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(10):1502–1511. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034033.95701.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Spear LP. Repeated restraint stress alters sensitivity to the social consequences of ethanol in adolescent and adult rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;96(2):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, Truxell E, Spear LP. Chronic intermittent ethanol exposure during adolescence: effects on social behavior and ethanol sensitivity in adulthood. Alcohol. 2014;48:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter-O'Hagen CS, Spear LP. Hormonal and physical markers of puberty and their relationship to adolescent-typical novelty-directed behavior. Dev Psychobiol. 2012;54(5):523–535. doi: 10.1002/dev.20610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter-O'Hagen C, Varlinskaya E, Spear L. Sex differences in ethanol intake and sensitivity to aversive effects during adolescence and adulthood. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(6):547–554. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall VL, Fischer EK, Bland ST. Isolation rearing attenuates social interaction-induced expression of immediate early gene protein products in the medial prefrontal cortex of male and female rats. Physiol Behav. 2012;107(3):440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker LR, Degoulet M, Morikawa H. Social deprivation enhances VTA synaptic plasticity and drug-induced contextual learning. Neuron. 2013;77(2):335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]