Abstract

Noroviruses are responsible for most acute nonbacterial epidemic outbreaks of gastroenteritis worldwide. To develop cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) for rapid identification of genogroup I and II (GI and GII) noroviruses (NoVs) in field specimens, mice were immunized with baculovirus-expressed recombinant virus-like particles (VLPs) corresponding to NoVs. Nine MAbs against the capsid protein were identified that detected both GI and GII NoV VLPs. These MAbs were tested in competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to identify common epitope reactivities to GI and GII VLPs. Patterns of competitive reactivity placed these MAbs into two epitope groups (groups 1 and 2). Epitopes for MAbs NV23 and NS22 (group 1) and MAb F120 (group 2) were mapped to a continuous region in the C-terminal P1 subdomain of the capsid protein. This domain is within regions previously defined to contain cross-reactive epitopes in GI and GII viruses, suggesting that common epitopes are clustered within the P1 domain of the capsid protein. Further characterization in an accompanying paper (B. Kou et al., Clin Vaccine Immunol 22:160–167, 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00519-14) revealed that MAb NV23 (epitope group 1) is able to detect GI and GII viruses in stool. Inclusion of the GI and GII cross-reactive MAb NV23 in antigen detection assays may facilitate the identification of GI and GII human noroviruses in stool samples as causative agents of outbreaks and sporadic cases of gastroenteritis worldwide.

INTRODUCTION

Noroviruses (NoVs) are the major cause of acute nonbacterial epidemic gastroenteritis in adults and children in both developing and industrialized countries (1–3). In the United States, NoVs cause 19 to 21 million cases each year (4, 5). NoV outbreaks have been identified in children (6), the elderly (7), military personnel (8, 9), immunocompromised individuals (10), restaurant patrons (11, 12), travelers to developing countries (13, 14), passengers of cruise ships (15), residents of health care facilities such as nursing homes (16, 17) and hospitals (18), and other populations housed in close quarters (19). The increasing incidence of NoV infections emphasizes the need to quickly detect and identify the causative agent, because early diagnosis of NoV infection can be crucial in the effective control of outbreaks and can decrease the secondary attack rate (20).

Currently, only one immunoassay, the Ridascreen norovirus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (3rd generation), is available for NoV diagnosis in the United States, and this assay is approved to be used only in outbreak settings due to its low sensitivity of detection. The difficulty in developing broadly detecting NoV diagnostics is due to the diversity of NoV strains. NoVs are classified into six genogroups (GI to GVI) based on phylogenetic analysis of the viral capsid (VP1) gene. Viruses within GI, GII, and GIV cause human infections. Genogroups are further subdivided into genotypes, and there are at least 9 GI and 22 GII genotypes (21, 22). The amino acid sequence diversity is <44% within a genogroup and >45% between genogroups (22). Clear relationships between genotypes and antigenicity have not yet been determined due to the lack of a cultivation system.

Expression of the 3′ end of the genome using the recombinant baculovirus system results in the formation of virus-like particles (VLPs) that are structurally and antigenically similar to the native virion (23–25). The major capsid protein, VP1, is structurally divided into the shell (S) domain, which forms the internal structural core of the particle, and the protruding (P) domain, which is exposed on the outer surface of the particle (23). The P domain is further subdivided into the P1 subdomain (residues 226 to 278 and 406 to 520 for GI.1 Norwalk virus [NV]) and the P2 subdomain (residues 279 to 405 for GI.1 NV) (23). P2 represents the most exposed surface of the viral particle and is involved in cellular histo-blood group antigen (HBGA) binding (26–28).

Despite X-ray crystallographic knowledge of several noroviruses, information is just beginning to emerge to define specific regions of the capsid protein containing cross-reactive epitopes. Most information on the antigenic characteristics of NoVs comes from the study of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) generated against VLPs from both GI and GII viruses (27, 29–40). The majority of these MAbs are genogroup specific and recognize only viruses closely related to the immunogen used to generate the MAb. The present study analyzed cross-reactive MAbs that recognize epitopes on both GI and GII VLPs that may be useful in the development of improved diagnostic assays to detect NoVs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies.

MAbs were isolated as previously described (33). A panel of 9 MAbs (NV23, NV37, NV3, NV57, NV7, NS22, NS941, F8, and F120) were generated against NoV VLPs. MAb NV23, NV37, and NV3 hybridomas were previously derived from spleen cells of mice immunized orally with recombinant Norwalk virus (NV; GI.1) (accession number M87661 [25, 41]) VLPs, while MAb F8 and F120 hybridomas were obtained from spleen cells of mice immunized orally with recombinant Kashiwa 47 virus (KAV; GII.13) (accession number AB078334 [33]) VLPs. MAb NV57 and NV7 hybridomas were obtained from spleen cells of mice immunized orally with NV VLPs. MAb NS22 and NS941 hybridomas were obtained from spleen cells of mice immunized orally with a mixture of NV and recombinant Snow Mountain virus (SMV; GII.2) (31) VLPs. Two previously characterized MAbs, NV3901 and NS14, were also used in this study (35).

The binding reactivities of these MAbs were characterized by direct ELISA against a panel of 4 GI VLPs and 7 GII VLPs (33). The GI VLPs used were generated from GI.1 Norwalk/1968 (NV; accession number M87661), GI.4 1643/2008 (accession number GQ413970), GI.6 TCH-099/2003 (accession number KC998959), and GI.7 TCH-060/2003 (accession number JN005886). The GII VLPs used were generated from GII.2 Snow Mountain/1976 (SMV; accession number AY134748) (31), GII.2 TCH-560/2002 (accession number KC998960), GII.3 TCH-577/2004 (accession number KF006265), GII.4 Houston virus TCH-186/2002 (HOV; accession number EU310927) (35), GII.4 Grimsby/1995 (GRV; accession number AJ004864) (42), GII.6 E99-13646/1999 (accession number GU930737), GII.7 TCH-134/2003 (accession number KF006266), GII.12 E00-13842/2000 (accession number KF006267), and GII.17 Katrina/2005 (accession number DQ438972). Ninety-six-well polyvinyl chloride plates (Dynatech, Chantilly, VA) were coated with purified NoV particles (100 μl of particles [1 μg/ml] in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with 200 μl 5% BLOTTO (Carnation nonfat milk) in PBS for 2 h at 37°C. After the plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), serial 2-fold dilutions of each MAb in 0.5% BLOTTO, beginning at 1:100, were added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed five times with PBS-T, and bound antibody was detected by addition of 100 μl of goat anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:3,000 dilution in 0.5% BLOTTO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were then washed five times with PBS-T and developed with 100 μl of TMB microwell peroxidase substrate system reagents (1:1 A:B; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 M H3PO4, and the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was read with a SpectraMAX M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Noncoated wells were used as negative controls. The positive-cutoff threshold was calculated as the mean for the negative-control wells plus three times the standard deviation for the negative-control wells.

Competition ELISA.

Two methods of competition ELISA were used. For the first competition ELISA, MAbs were biotinylated using an antibody biotinylation kit (American Qualex Manufacturers, San Clemente, CA). Briefly, MAbs (5 mg/ml) were dialyzed against a 1:10 dilution of carbonate buffer overnight. A long-chain N-hydroxysuccinimide ester biotin (NHS-LC-biotin) solution (0.5 mg biotin/0.5 ml distilled water) was added to the protein solution, to a final concentration of 74 μg biotin/mg protein, and gently shaken for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then passed over a Sephadex G25 column. The biotin conjugate was eluted off the column by use of PBS, concentrated, and stored at 4°C. Microtiter plates (Sumitomo Bakelite Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 to 500 ng/well of GI.1 NV or GII.4 GRV (42) VLPs in 100 μl of 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Each well was washed twice with PBS-T and blocked with 5% BLOTTO in PBS-T for at least 1 h at room temperature. In separate tubes, optimized concentrations of biotinylated MAb (which produced an OD of 0.5 to 2.0 when no competitor MAb was present) were added to diluted competitor MAb (diluted ×64, ×256, ×1,024, ×4,096, and ×16,384) in PBS (pH 7.2). Following two washes with PBS-T, 100-μl aliquots of the MAb mixtures were added to duplicate wells, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After washing four times with PBS-T, 50 μl of a 1:1,000 to 1:2,000 dilution of HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After washing, 50 μl of o-phenylenediamine–H2O2 (0.5 mg/ml o-phenylenediamine, 0.002% H2O2, 0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 5.5) was added as a substrate and developed for 10 min. The color reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μl of 2 N H2SO4. The OD405 and OD630 were determined. The OD average for duplicates was calculated, and the percentage of competition or enhanced binding was determined for all competitor MAb concentrations (×64, ×256, ×1,024, ×4,096, and ×16,384), based on the value for the PBS control. The value for biotinylated MAb binding to the coating VLPs in the absence of competitor MAb was defined as zero.

The second method, from the work of Hale et al. (29), was used to analyze competition between MAbs NV3901, NS14, and NV23. MAbs were purified using protein G columns (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One MAb, at a concentration of 2 μg/ml in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, was used to coat flat-bottomed polyvinyl chloride microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Alexandria, VA) overnight at 4°C. In separate tubes, a constant concentration of NV or HOV VLPs (based on each MAb, to give an OD450 between 0.5 and 0.6) was added to decreasing concentrations of competitor MAb (5, 1, 0.5, 0.1, and 0.05 μg/ml) in 0.5% BLOTTO in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. A control containing VLPs in 0.5% BLOTTO without competitor was included in each plate. The antibody-coated microtiter plates were washed three times with PBS-T and blocked with 5% BLOTTO for 1 h at 37°C. Following six washes with PBS-T, each of the VLP-MAb reaction mixtures was added to triplicate wells, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After washing six times, a 1:5,000 dilution of rabbit anti-NV VLP or rabbit anti-HOV hyperimmune serum in 0.5% BLOTTO was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Following incubation, plates were again washed, and a 1:5,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added. Plates were incubated for an additional hour and then washed again. To develop the ELISA, 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) was added to each well, and the color reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 M H3PO4. The optical density at 450 nm was read, and the average value for triplicates was calculated. The percentage of competition was determined for the competitor MAb concentrations, based on the value for the PBS control, where the value of VLP binding to the coating MAb in the absence of competitor MAb was defined as zero. Homotypic competition was included as a positive control for all coating MAbs.

Cloning, expression, and analysis of norovirus fusion proteins.

Characterization of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–norovirus fusion protein deletion mutants has been described previously (35). Numbering of the constructs indicates the N-terminal (first) and C-terminal (last) norovirus residues contained within the constructs. NoV fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells (Novagen, Madison, WI) and purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The proteins were detected using a polyclonal goat anti-GST antibody (Amersham Pharmacia) at a dilution of 1:8,000, a mouse hyperimmune anti-NV VLP serum at a dilution of 1:5,000, or a rabbit hyperimmune anti-HOV VLP serum at a dilution of 1:5,000 in 0.5% BLOTTO. MAb ascites fluid was used for detection, at a dilution of 1:1,000. All secondary antibodies used were conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Membranes were developed by chemiluminescence, using Western Lightning detection reagent (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Inc., Boston, MA) following the manufacturer's protocol.

RESULTS

Monoclonal antibodies to norovirus VLPs that recognize both genogroup I and genogroup II viruses can be separated into two epitope groups.

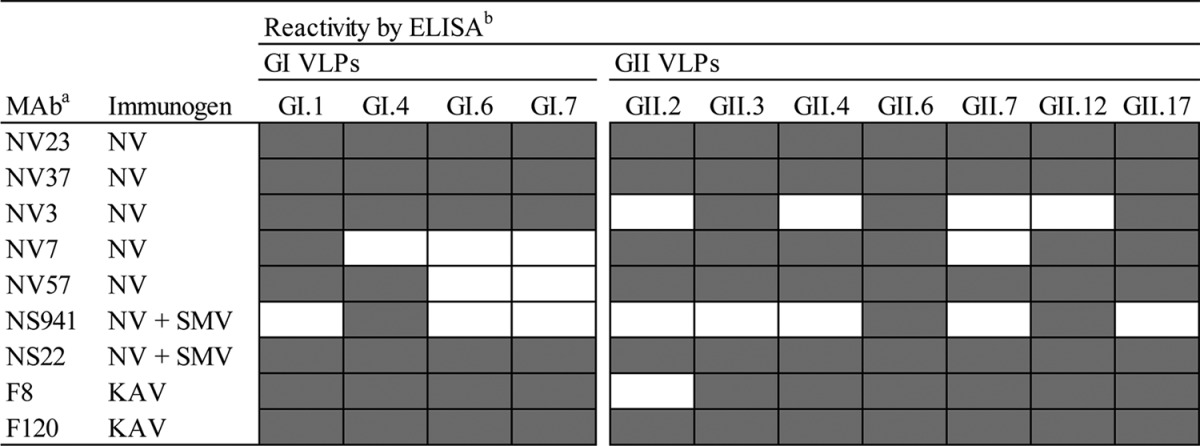

We previously reported the characterization of MAbs generated against NoV VLPs with respect to their reactivity to GI and GII VLPs by ELISA or Western blotting (33). MAbs NV23, NV37, and NV3, obtained from mice administered GI.1 NV VLPs perorally, and F8 and F120, obtained from mice administered GII.13 KAV VLPs perorally, recognized both GI (GI.1 NV by ELISA and GI.1 NV and Seto 124 [SeV; accession number AB031013], GI.2 Funabashi 258 [FUV; accession number AB078335], and G1.4 Chiba 407 [CV; accession number AB022679] by Western blotting) and GII (GII.2 SMV, GII.4 GRV and Narita 104 [NAV; accession number AB078336], GII.6 Ueno 7K [UEV; accession number AB078337], GII.12 Chitta 76 [CHV; accession number AB032758], and GII.13 KAV by ELISA) VLPs (33). Additional MAbs NV57 and NV7 were obtained from mice administered NV VLPs perorally, and NS22 and NS941 were obtained from mice administered NV and SMV VLPs perorally. Subsequent characterization of reactivities to a larger panel of GI and GII VLPs by ELISA (Table 1) showed that each MAb recognized at least a subset of both GI and GII VLPs by ELISA, suggesting that each MAb detects a common epitope in both GI and GII VLPs.

TABLE 1.

Reactivities of MAbs against GI and GII VLPs by ELISA

All MAbs were generated from spleen cells of mice immunized perorally with the indicated immunogen.

Shaded cells indicate positive reactivity, and white cells indicate reactivity below the limit of detection.

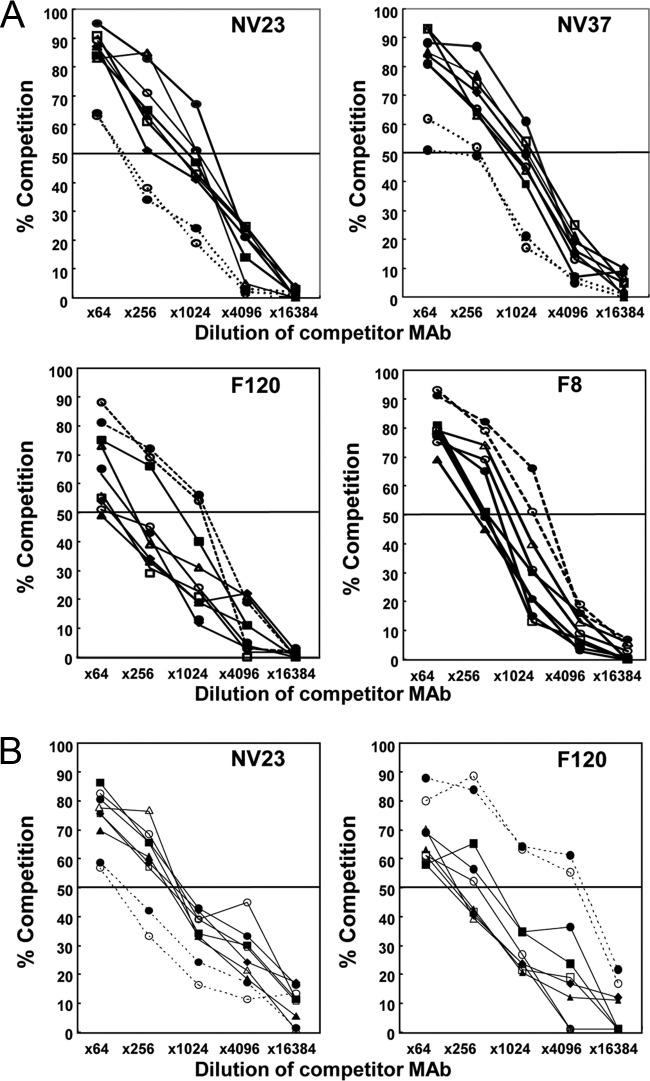

To determine whether the MAbs detect similar or different epitopes in GI and GII VLPs, each of these MAbs was then tested in competition ELISAs with GI.1 NV and GII.4 GRV VLPs to classify them into epitope groups (Fig. 1). In competition ELISAs with GI.1 NV VLPs, homotypic competition for the 9 MAbs was found to vary between 10 and 90% at the highest concentration (×64; about 500 μg/ml) of competitor antibody used in the ELISAs (Fig. 1A). Each one of MAbs NV23, NV37, NV3, NV57, NV7, NS22, and NS941 showed 80% or more competition with itself and the 6 other MAbs (Fig. 1A, top panels [biotinylated MAb NV23 or NV37]). When MAb F8 or F120 was used as the competitor MAb, only 50 to 60% competition was observed (at a ×64 concentration) for biotinylated MAb NV23, NV37, NV3, NV57, NV7, NS22, or NS941 (Fig. 1A, top panels [biotinylated MAb NV23 or NV37]).

FIG 1.

Competition ELISAs for biotinylated MAbs, using GI.1 and GII.4 VLPs. Biotinylated monoclonal antibodies NV23, NV37, F120, and F8 (A) or NV23 and F120 (B) were mixed with competitor monoclonal antibodies NV23 (●, solid lines), NV37 (○, solid lines), NV3 (▲), NV57 (△), NV7 (■), NS22 (□), NS941 (◆), F8 (●, dotted lines), and F120 (○, dotted lines) and then used to detect GI.1 NV (A) or GII.4 (B) VLPs bound to microtiter plates. The 50% cutoff for significant competition is indicated by a horizontal line. Homotypic and heterotypic competition was observed.

Reduced levels of competition were seen when MAbs NV23, NV37, NV3, NV57, NV7, NS22, and NS941 were used as competitor MAbs with biotinylated MAb F120 or F8 compared to the levels of homotypic competition (Fig. 1A, bottom panels), although to a lesser extent than that seen when F8 or F120 was used as the competitor MAb against these MAbs (Fig. 1A, top panels). This difference may have been due to a conformational change in the epitope recognized by the antibody leading to a reduced affinity of binding. Alternatively, the epitopes may overlap such that one MAb causes steric hindrance and the other does not. Similar competition patterns were obtained when GII.4 GRV VLPs were used as a coating antigen with NV23 and F120 (Fig. 1B, left and right panels, respectively).

The 9 MAbs were classified into two groups according to their competition ELISA patterns, as follows: group 1, NV23, NV37, NV3, NV57, NV7, NS22, and NS941; and group 2, F8 and F120. The results obtained suggest that the 7 MAbs of group 1 recognize the same or almost identical epitopes. Group 2 MAbs likely recognize an epitope that is similar to or closely overlaps that of group 1.

Group 1 and 2 monoclonal antibodies recognize an epitope within the C-terminal P1 domain.

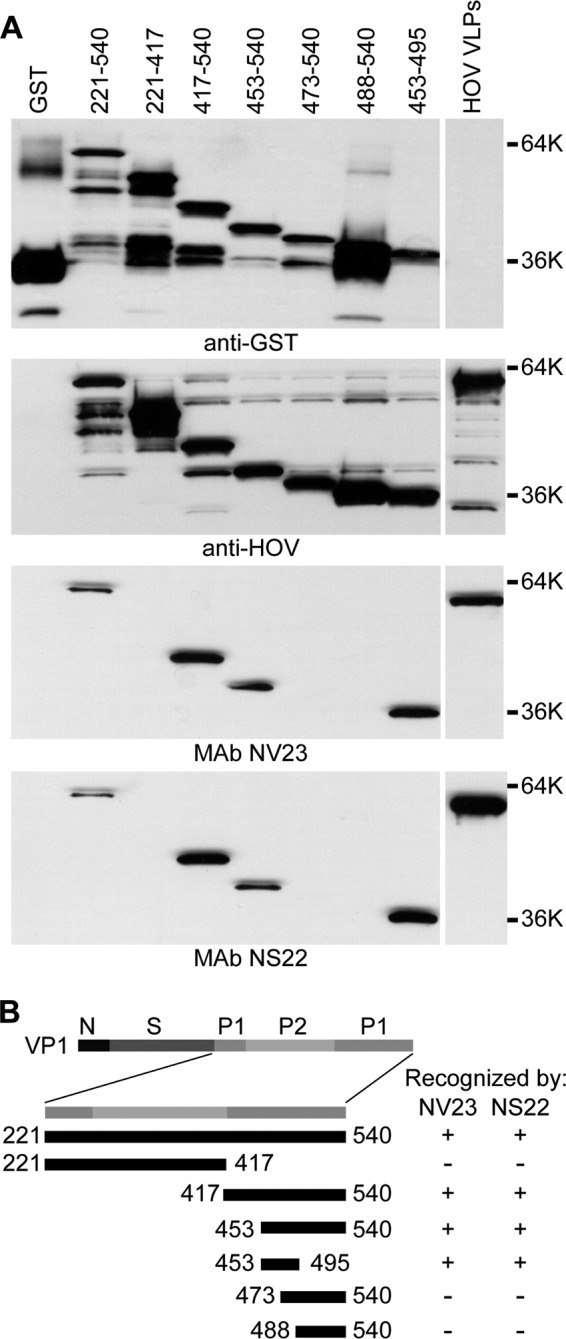

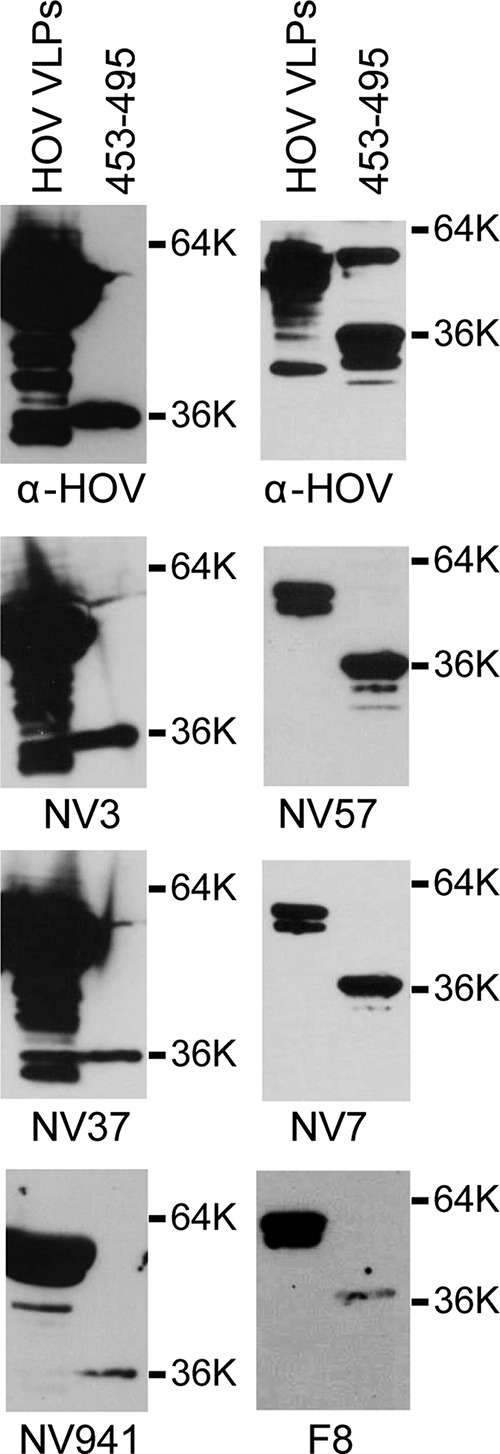

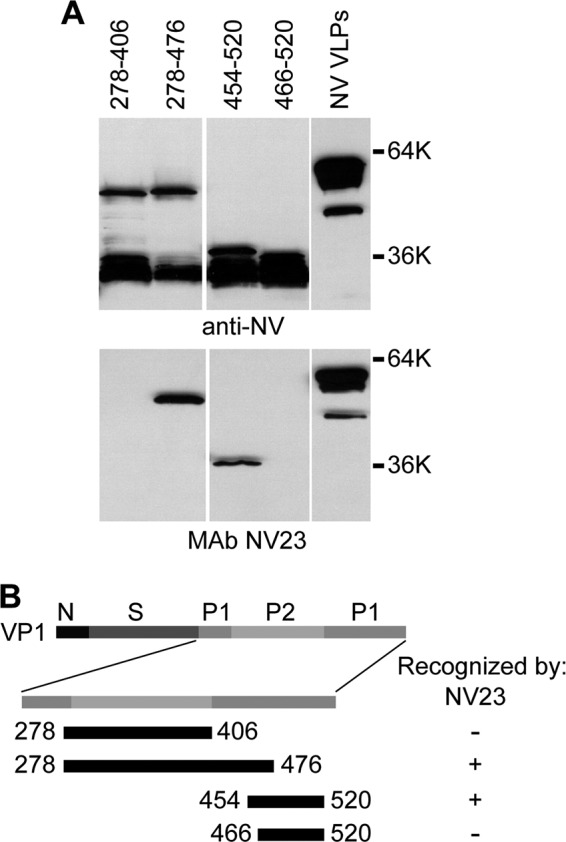

To identify the binding site(s) for epitope group 1 and 2 cross-reactive MAbs, a subset of MAbs from each epitope group was tested by Western blot analysis for the ability to recognize deletion mutants of the GII.4 HOV VP1 capsid protein. From epitope group 1, MAbs NV23 and NS22 were mapped because these MAbs were identified to react with GI, GII, and GIV VLPs by both direct ELISA and capture ELISA in an accompanying paper by Kou et al. (43). Both NV23 and NS22 produced the same pattern of recognition (Fig. 2) and detected amino acids 453 to 495 but failed to detect amino acids 473 to 540, which defined the binding region for these monoclonal antibodies as being contained within GII.4 HOV amino acids 453 to 472 (corresponding to GI.1 NV amino acids 437 to 457). Although similar to NV23 and NS22, each of the other MAbs from epitope group 1 (NV3, NV7, NV37, NV57, and NV941), as well as epitope group 2 MAb F8, detected the minimal HOV 453–495 construct (Fig. 3), but these were not mapped further because they lacked reactivity to VLPs in a capture ELISA. Analysis of MAb NV23 binding to GI.1 NV deletion mutants confirmed that NV23 bound to an overlapping sequence within the NV capsid protein, with the minimal binding region, based on available constructs, comprised of amino acids 406 to 466 (Fig. 4).

FIG 2.

Mapping of epitope group 1 monoclonal antibodies NV23 and NS22. (A) HOV VLPs, GST, and purified GST-tagged HOV capsid protein deletion constructs containing the indicated residues were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GST antiserum, polyclonal rabbit anti-HOV VLP antiserum, and MAbs NV23 and NS22, as indicated below the blots. (B) Schematic representation of the locations of the constructs relative to the full-length VP1 protein, with a summary of recognition by NV23 and NS22. GST, purified GST protein; HOV VLPs, purified Houston virus GII.4 VLPs.

FIG 3.

Monoclonal antibodies detect HOV amino acids 453 to 495. GII.4 HOV VLPs and a purified GST-tagged HOV capsid construct with amino acids 453 to 495 were analyzed by Western blotting with polyclonal rabbit anti-HOV VLP antiserum and MAbs NV3, NV37, NS941, NV57, NV7, and F8, as indicated below the blots.

FIG 4.

Mapping of epitope group 1 MAb NV23. (A) GI.1 NV VLPs and purified GST-tagged NV capsid protein deletion constructs containing the indicated residues were analyzed by Western blotting with polyclonal rabbit anti-NV VLP antiserum and MAb NV23, as indicated below the blots. (B) Schematic representation of the locations of the constructs relative to the full-length VP1 protein, with a summary of recognition by NV23.

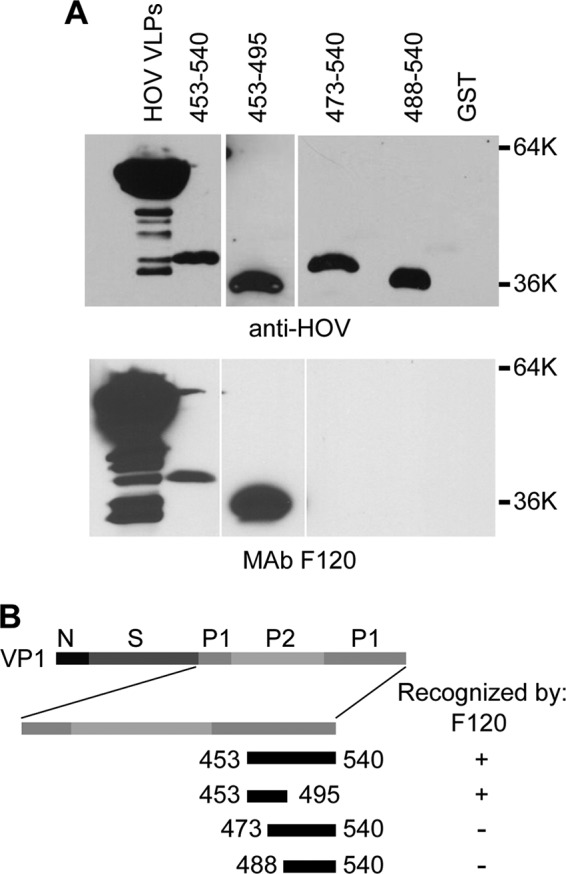

Western blot analysis with the GII.4 HOV VP1 capsid protein deletion mutants was performed to characterize the binding site of the epitope group 2 MAb F120. Similar to the epitope group 1 MAbs, the epitope group 2 MAb F120 also detected GII.4 HOV amino acids 453 to 495 and failed to detect amino acids 473 to 540, indicating that the epitopes for groups 1 and 2 map to amino acids 453 to 472 (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

Mapping of epitope group 2 MAb F120. (A) Purified GST-tagged HOV capsid protein deletion constructs containing the indicated residues were analyzed by Western blotting with polyclonal rabbit anti-HOV VLP antiserum (top) or F120 (bottom). (B) Schematic representation of the locations of the constructs relative to the full-length VP1 protein, with a summary of recognition by F120. GST, purified GST protein; HOV VLPs, purified Houston virus VLPs.

NoV monoclonal antibodies bind to distinct sites of the norovirus capsid protein.

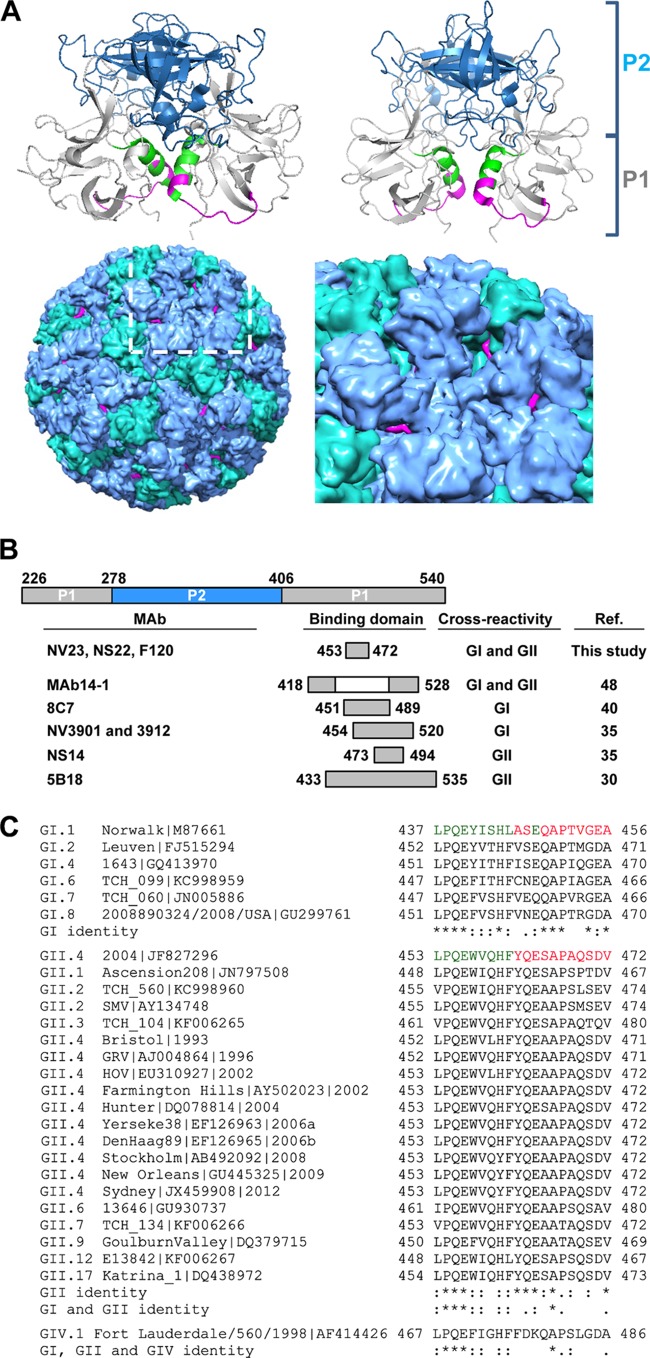

The location of the domain that epitope group 1 MAbs NV23 and NS22 and epitope group 2 MAb F120 detect is shown in the crystal structures of the GI.1 NV (amino acids 437 to 457) and GII.4 2004 variant (amino acids 453 to 472) VP1 P domains (Fig. 6A, top left and right panels, respectively). Previous work by our group identified the epitopes for MAbs NV3901 and NS14 (35). MAb NV3901 is specific for GI viruses, and its epitope maps to NV amino acids 454 to 520, and specifically to E472, which forms a salt bridge with K514 (35). MAb NS14 recognizes GII viruses, and its epitope maps to HOV amino acids 473 to 495. Alignment of the binding sites of these MAbs shows that all of the MAbs recognize overlapping or adjacent regions of the NoV capsid protein (Fig. 6B). Alignment of the epitope group 1 and group 2 MAb binding domains from the test VLPs used in this study and the companion study of Kou et al. (43) shows a number of conserved amino acids, with only the alanine being completely conserved within this domain (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

Location of binding site for epitope group 1 MAbs NV23 and NS22 and epitope group 2 MAb F120. (A) Locations of amino acids corresponding to the epitope binding sites for epitope group 1 MAbs NV23 and NS22 and epitope group 2 MAb F120 on the crystal structures of GI.1 NV (amino acids 437 to 457; PDB accession number 1IHM) (top right) and GII.4 HOV (amino acids 453 to 472; PDB accession number 3SKB) (top left) P domain dimers, prepared using PyMOL. The ribbon structure for P1 is shown in gray, and that for P2 is in blue; the residues corresponding to the minimal binding domain are indicated in green, with the surface-exposed residues shown in magenta. (Bottom left) NV VLP crystal structure (VIPER database accession number 1IHM), with A-B dimers in blue, C-C dimers in green, and surface-exposed residues in the MAb minimal binding domain in magenta, determined using Chimera. The boxed area (white) is magnified (bottom right) and shows the P2 domain surrounding the 5-fold axis, with the MAb surface-exposed binding residues shown in magenta. (B) Alignment of binding sites for cross-reactive MAbs. The binding site for each MAb is shown relative to its position within the P domain. Amino acid numbers for the MAbs characterized in this study and for NS14 correspond to the GII.4 HOV sequence (GenBank accession number EU310927), amino acid numbers for NV3901 correspond to the GI.1 NV sequence (accession number M87661), amino acid numbers for MAb14-1 correspond to the GII.4 1207 sequence (accession number DQ975270), amino acid numbers for 8C7 correspond to the GI.1 Norwalk virus sequence (NV 96-908; accession number AB028247), and amino acid numbers for 5B18 correspond to the GII.10 Vietnam026 sequence (accession number AF504671). (C) Alignment of the MAb binding domains in the P1 capsid sequence for the indicated virus strains. The amino acid numbering corresponds to each virus strain|GenBank accession number. The minimal binding domains for MAbs NV23, NS22, and F120 in the GI.1 NV and GII.4 2004 HOV capsid regions are indicated in green, with the surface-exposed residues shown in magenta. Symbols: *, identical amino acids; :, different but highly conserved amino acids; ., amino acids that are somewhat similar.

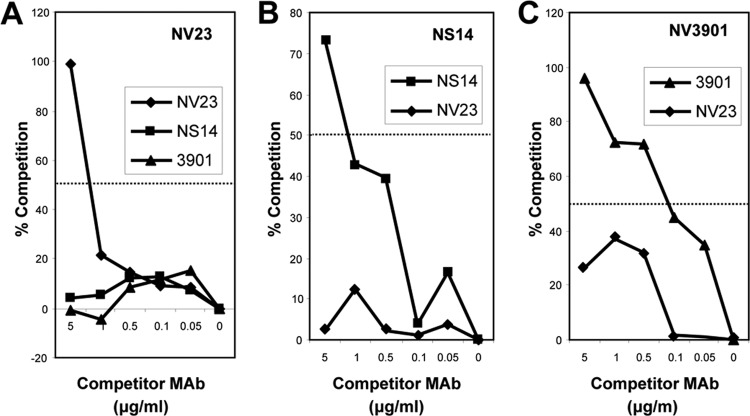

MAb NV23 is broadly reactive and detects GI and GII strains of virus (43), whereas NV3901 and NS14 are GI and GII specific, respectively. To further characterize MAb NV23 and to determine whether the binding site for NV23 is distinct from the sites for NS14 and NV3901, we performed competition ELISAs using MAbs NV23 (Fig. 7A), NS14 (Fig. 7B), and NV3901 (Fig. 7C). Because we found that the VLP conformation changed upon direct coating of ELISA plates, we performed competition ELISAs by capturing the VLPs by use of MAbs. Neither MAb NV3901 nor NS14 competed for VLP binding to MAb NV23 when used as either the coating or competitor antibody (Fig. 7). However, NV23 did show some level of competition with NV3901 (although it was no greater than 50%), which suggests that NV23 may inhibit NV3901 binding as a result of steric hindrance. These results confirm that MAbs NV23, NS14, and NV3901 recognize distinct epitopes within the C-terminal P1 domain of VP1.

FIG 7.

Competition ELISAs between GI-specific (3901), GII-specific (NS14), and GI- and GII-specific (NV23) monoclonal antibodies. (A) NV23; (B) NS14; (C) 3901. The coating antibody is indicated at the top of the graph, and the competitor MAbs are shown in the box. The 50% cutoff for significant competition is indicated by a horizontal line.

DISCUSSION

Noroviruses are a major cause of sporadic cases and epidemic outbreaks of gastroenteritis. To effectively implement infection control measures following outbreaks, sensitive and rapid diagnostic assays are needed to identify the causative agents of viral gastroenteritis. Containment of outbreaks relies on rapid diagnosis: in a previous study, identification of the causative agent within 3 days versus 4 or more days following the first case resulted in outbreak containment an average of 6 days sooner (7.9 compared to 15.4 days) (20). Many currently available immunologic reagents used to study noroviruses are genotype specific, which limits their usefulness for identifying antigenically distinct viruses. Broadly genogroup-cross-reactive antibodies are needed for rapid identification of NoVs in field specimens. Identification of cross-reactive epitopes on the NoV capsid proteins also provides important information regarding the antigenic characteristics of these viruses.

The present work extends our previous reports (33, 44) that oral immunization with different VLPs can generate cross-reactive NoV MAbs. These MAbs were found to compete for binding on GI.1 and GII.4 VLPs, and the epitopes of MAbs NV23, NS22, and F120 map to the C-terminal P1 subdomain of the capsid protein, which includes amino acids 453 to 472 in the GII.4 HOV sequence. Although the competition ELISA segregated MAbs NV23 and NS22 into epitope group 1 and F120 into epitope group 2, the epitopes for these MAbs mapped to the same region of the capsid, suggesting that the epitopes for these MAbs are overlapping but not the same and may have competed for binding due to steric hindrance. A full understanding of this observation may be obtained by structural studies of VLP-Fab complexes, which is outside the scope of this report.

Interestingly, the domain containing amino acids 453 to 472 overlaps or is adjacent to the region we previously described that contains epitopes for genogroup-specific MAbs NV3901 (GI specific) and NS14 (GII specific) (35). The epitopes for NV23 characterized in this study and those for NV3901 and NS14 appear to be distinct based on competition ELISAs. The C-terminal domain, while not any more highly conserved than the P1 subdomain overall, contains conserved residues that are suitable for acting as cross-reactive NoV epitopes (Fig. 6C). For the MAbs mapped in this study, the domain analogous to amino acids 453 to 472 in the GII.4 HOV structure comprises amino acids 437 to 457 in the GI.1 NV structure (26) (Fig. 6A). In the context of the NV VLP structure, the surface-exposed residues in this domain can be seen within the 5-fold axis in the P1 subdomain (23) (Fig. 6A, bottom panels; surface-exposed residues are labeled in magenta). Interestingly, the conserved glutamic acid/glutamine at position 448 (numbered according to the NV sequence) is not surface exposed. However, the proline at position 451 (numbered according to the NV sequence) is conserved in all GI and GII sequences, with the exception of the GII.7 virus strain. Modeling the threonine residue in GII.7 in place of the proline in the context of the GII.4 2004 variant P domain indicates that the threonine is retained on the surface of the structure. The remainder of surface-exposed residues following position 451 (numbered according to the NV sequence) are surface exposed in both the NV and GII.4 2004 variant structures (Fig. 6A, top panels), suggesting that this domain may be responsible for the common GI and GII reactivity.

The nine MAbs described in this study detected both GI and GII VLPs by direct ELISA when ELISA plates were coated with the VLPs in PBS. However, Kou et al. observed an increase or decrease in reactivity to a subset of VLPs in the direct ELISA with MAbs NV3 and NV57 when the VLPs were plated in water (43). Differences in GI.1 and GII.4 attachment efficiencies in the presence of phosphate have been described previously and were attributed to a differential response of the unique arrangement of exposed amino acid residues on the capsid surface of each VLP strain, which may explain the different reactivities of MAbs to VLPs plated in water versus PBS (45). Furthermore, the reactivities of these MAbs differed in a capture ELISA compared to the direct ELISA. The reactivity in the capture ELISA correlated with the results of surface plasmon resonance analysis, which revealed that NV23 and NS22 bound GI and GII VLPs with high affinities, while NV57 bound only GII test VLPs. In contrast, NV37 bound only GI.1 VLPs, and NV3 did not bind any test VLPs. Additionally, F120 and F8, similar to the epitope group 1 MAbs NV3, NV7, NV37, NV57, and NS941, did not detect GI or GII VLPs in a capture ELISA, indicating that these MAbs interact with amino acids that are not surface exposed on VLPs in solution but do interact with amino acids that are exposed due to binding to the ELISA plate. These results support the hypothesis that the conformation of the VLPs changes, either due to the buffer used to plate the VLPs or because of the direct coating of the wells of ELISA plates with VLPs, thus exposing residues that are buried within the VLPs in solution.

The presence of broadly cross-reactive epitopes on VLPs was demonstrated by the reactivity of polyclonal antiserum as well as monoclonal antibodies generated against NoV VLPs that detected both GI and GII VLPs (29, 33, 35, 46–48). Additional evidence that the C-terminal P domain contains cross-reactive epitopes was provided by the identification of MAb14-1. This MAb, which detects 15 recombinant virus-like particles, for the GI.1, GI.4, GI.8, GI.3, GII.1 to GII.7, GII.12 to GII.14, and GII.16 genotypes (renumbered according to the work of Zheng et al. [22] and Kroneman et al. [21]), was mapped to a conformational epitope involving amino acids 418 to 426 and 526 to 534, regions surrounding amino acids 453 to 472, identified as the site for the cross-reactive MAbs characterized in this study (Fig. 6B) (48). Additionally, the crystal structure of monoclonal antibody 5B18, which is currently in use in a commercial norovirus ELISA detection kit (Denka Seiken, Japan) and binds numerous GII genotypes but not GI NoVs, was found to interact with amino acids Val433, Glu496, Asn530, Tyr533, Thr534, and Leu535 on the GII.10 P domain (30). However, this region of the protruding domain was determined to be occluded in the crystal structure and led to the suggestion that NoV particles are capable of extreme conformational flexibility to allow this monoclonal antibody to bind to its epitope (30).

The only norovirus diagnostic immunoassay currently approved for use in the United States is the Ridascreen norovirus 3rd-generation antigen ELISA. However, it is currently approved for use only in outbreak settings, because it lacks sensitivity (49–52). The increasing evidence that noroviruses are undergoing antigenic variation highlights the need for diagnostic assays that detect broadly cross-reactive epitopes (53–55). We have identified a broadly cross-reactive epitope in the C-terminal P1 domain that is surface exposed; the majority of these residues are dissimilar between human norovirus strains, suggesting that this region may remain invariant while other domains of the virus are undergoing antigenic variation. Therefore, inclusion of MAb NV23 in antigen detection assays may facilitate the identification of GI and GII human noroviruses in stool samples as the causative agents of outbreaks and sporadic cases of gastroenteritis worldwide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants NIH R01 AI38036 and P01 AI57788, training grant T32 A107471 (to T.D.P.), and grant P30 CA125123, which funds the Recombinant Protein and Monoclonal Antibody Production Shared Resource at Baylor College of Medicine, from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; and by the John S. Dunn Research Foundation (to R.L.A.).

M.K.E. is named as an inventor on patents related to cloning of the Norwalk virus genome, and M.K.E., T.T., and N.K. receive royalties from commercialization activities through Baylor College of Medicine for NoV monoclonal antibody reagents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. 2009. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 361:1776–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2006. The epidemiologic and clinical importance of norovirus infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 35:275–290. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo HL, Ajami N, Atmar RL, Dupont HL. 2010. Noroviruses: the leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Discov Med 10:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall AJ, Lopman BA, Payne DC, Patel MM, Gastanaduy PA, Vinje J, Parashar UD. 2013. Norovirus disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1198–1205. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MM, Widdowson MA, Glass RI, Akazawa K, Vinje J, Parashar UD. 2008. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis 14:1224–1231. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green KY, Belliot G, Taylor JL, Valdesuso J, Lew JF, Kapikian AZ, Lin FY. 2002. A predominant role for Norwalk-like viruses as agents of epidemic gastroenteritis in Maryland nursing homes for the elderly. J Infect Dis 185:133–146. doi: 10.1086/338365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyams KC, Malone JD, Kapikian AZ, Estes MK, Xi J, Bourgeois AL, Paparello S, Hawkins RE, Green KY. 1993. Norwalk virus infection among Desert Storm troops. J Infect Dis 167:986–987. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp TW, Hyams KC, Watts D, Trofa AF, Martin GJ, Kapikian AZ, Green KY, Jiang X, Estes MK, Waack M. 1995. Epidemiology of Norwalk virus during an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis aboard a US aircraft carrier. J Med Virol 45:61–67. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890450112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roddie C, Paul JP, Benjamin R, Gallimore CI, Xerry J, Gray JJ, Peggs KS, Morris EC, Thomson KJ, Ward KN. 2009. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and norovirus gastroenteritis: a previously unrecognized cause of morbidity. Clin Infect Dis 49:1061–1068. doi: 10.1086/605557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels NA, Bergmire-Sweat DA, Schwab KJ, Hendricks KA, Reddy S, Rowe SM, Fankhauser RL, Monroe SS, Atmar RL, Glass RI, Mead P. 2000. A foodborne outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with Norwalk-like viruses: first molecular traceback to deli sandwiches contaminated during preparation. J Infect Dis 181:1467–1470. doi: 10.1086/315365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AJ, McCarthy N, Saldana L, Ihekweazu C, McPhedran K, Adak GK, Iturriza-Gomara M, Bickler G, O'Moore E. 2012. A large foodborne outbreak of norovirus in diners at a restaurant in England between January and February 2009. Epidemiol Infect 140:1695–1701. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811002305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajami N, Koo H, Darkoh C, Atmar RL, Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, Flores J, Dupont HL. 2010. Characterization of norovirus-associated traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 51:123–130. doi: 10.1086/653530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, Neill FH, Atmar RL, Ericsson CD, Okhuysen PC, Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Steffen R, Dupont HL. 2010. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to Guatemala, India, and Mexico. J Clin Microbiol 48:1673–1676. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02072-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wikswo ME, Cortes J, Hall AJ, Vaughan G, Howard C, Gregoricus N, Cramer EH. 2011. Disease transmission and passenger behaviors during a high morbidity norovirus outbreak on a cruise ship, January 2009. Clin Infect Dis 52:1116–1122. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trivedi TK, DeSalvo T, Lee L, Palumbo A, Moll M, Curns A, Hall AJ, Patel M, Parashar UD, Lopman BA. 2012. Hospitalizations and mortality associated with norovirus outbreaks in nursing homes, 2009–2010. JAMA 308:1668–1675. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calderon-Margalit R, Sheffer R, Halperin T, Orr N, Cohen D, Shohat T. 2005. A large-scale gastroenteritis outbreak associated with norovirus in nursing homes. Epidemiol Infect 133:35–40. doi: 10.1017/S0950268804003115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhinehart E, Walker S, Murphy D, O'Reilly K, Leeman P. 2012. Frequency of outbreak investigations in US hospitals: results of a national survey of infection preventionists. Am J Infect Control 40:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yee EL, Palacio H, Atmar RL, Shah U, Kilborn C, Faul M, Gavagan TE, Feigin RD, Versalovic J, Neill FH, Panlilio AL, Miller M, Spahr J, Glass RI. 2007. Widespread outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis among evacuees of Hurricane Katrina residing in a large “megashelter” in Houston, Texas: lessons learned for prevention. Clin Infect Dis 44:1032–1039. doi: 10.1086/512195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopman BA, Reacher MH, Vipond IB, Hill D, Perry C, Halladay T, Brown DW, Edmunds WJ, Sarangi J. 2004. Epidemiology and cost of nosocomial gastroenteritis, Avon, England, 2002–2003. Emerg Infect Dis 10:1827–1834. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.030941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroneman A, Vega E, Vennema H, Vinje J, White PA, Hansman G, Green K, Martella V, Katayama K, Koopmans M. 2013. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch Virol 158:2059–2068. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng DP, Ando T, Fankhauser RL, Beard RS, Glass RI, Monroe SS. 2006. Norovirus classification and proposed strain nomenclature. Virology 346:312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann MG, Estes MK. 1999. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science 286:287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green KY, Lew JF, Jiang X, Kapikian AZ, Estes MK. 1993. Comparison of the reactivities of baculovirus-expressed recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen with those of the native Norwalk virus antigen in serologic assays and some epidemiologic observations. J Clin Microbiol 31:2185–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham DY, Estes MK. 1992. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol 66:6527–6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi JM, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2008. Atomic resolution structural characterization of recognition of histo-blood group antigens by Norwalk virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:9175–9180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803275105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higo-Moriguchi K, Shirato H, Someya Y, Kurosawa Y, Takeda N, Taniguchi K. 2014. Isolation of cross-reactive human monoclonal antibodies that prevent binding of human noroviruses to histo-blood group antigens. J Med Virol 86:558–567. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanker S, Choi JM, Sankaran B, Atmar RL, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2011. Structural analysis of histo-blood group antigen binding specificity in a norovirus GII.4 epidemic variant: implications for epochal evolution. J Virol 85:8635–8645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00848-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hale AD, Tanaka TN, Kitamoto N, Ciarlet M, Jiang X, Takeda N, Brown DW, Estes MK. 2000. Identification of an epitope common to genogroup 1 “Norwalk-like viruses.” J Clin Microbiol 38:1656–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansman GS, Taylor DW, McLellan JS, Smith TJ, Georgiev I, Tame JR, Park SY, Yamazaki M, Gondaira F, Miki M, Katayama K, Murata K, Kwong PD. 2012. Structural basis for broad detection of genogroup II noroviruses by a monoclonal antibody that binds to a site occluded in the viral particle. J Virol 86:3635–3646. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06868-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy ME, Kramer SF, Treanor JJ, Estes MK. 1997. Human calicivirus genogroup II capsid sequence diversity revealed by analyses of the prototype Snow Mountain agent. Arch Virol 142:1469–1479. doi: 10.1007/s007050050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy ME, Tanaka TN, Kitamoto N, White LJ, Ball JM, Jiang X, Estes MK. 1996. Antigenic mapping of the recombinant Norwalk virus capsid protein using monoclonal antibodies. Virology 217:252–261. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitamoto N, Tanaka T, Natori K, Takeda N, Nakata S, Jiang X, Estes MK. 2002. Cross-reactivity among several recombinant calicivirus virus-like particles (VLPs) with monoclonal antibodies obtained from mice immunized orally with one type of VLP. J Clin Microbiol 40:2459–2465. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2459-2465.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindesmith LC, Beltramello M, Donaldson EF, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Debbink K, Lanzavecchia A, Baric RS. 2012. Immunogenetic mechanisms driving norovirus GII.4 antigenic variation. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002705. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker TD, Kitamoto N, Tanaka T, Hutson AM, Estes MK. 2005. Identification of genogroup I and genogroup II broadly reactive epitopes on the norovirus capsid. J Virol 79:7402–7409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7402-7409.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parra GI, Azure J, Fischer R, Bok K, Sandoval-Jaime C, Sosnovtsev SV, Sander P, Green KY. 2013. Identification of a broadly cross-reactive epitope in the inner shell of the norovirus capsid. PLoS One 8:e67592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parra GI, Abente EJ, Sandoval-Jaime C, Sosnovtsev SV, Bok K, Green KY. 2012. Multiple antigenic sites are involved in blocking the interaction of GII.4 norovirus capsid with ABH histo-blood group antigens. J Virol 86:7414–7426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06729-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanstrom J, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Yount B, Baric RS. 2014. Characterization of blockade antibody responses in GII.2.1976 Snow Mountain virus-infected subjects. J Virol 88:829–837. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02793-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoda T, Suzuki Y, Terano Y, Yamazaki K, Sakon N, Kuzuguchi T, Oda H, Tsukamoto T. 2003. Precise characterization of norovirus (Norwalk-like virus)-specific monoclonal antibodies with broad reactivity. J Clin Microbiol 41:2367–2371. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2367-2371.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoda T, Terano Y, Suzuki Y, Yamazaki K, Oishi I, Kuzuguchi T, Kawamoto H, Utagawa E, Takino K, Oda H, Shibata T. 2001. Characterization of Norwalk virus GI specific monoclonal antibodies generated against Escherichia coli expressed capsid protein and the reactivity of two broadly reactive monoclonal antibodies generated against GII capsid towards GI recombinant fragments. BMC Microbiol 1:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes MK. 1993. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology 195:51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hale AD, Crawford SE, Ciarlet M, Green J, Gallimore C, Brown DW, Jiang X, Estes MK. 1999. Expression and self-assembly of Grimsby virus: antigenic distinction from Norwalk and Mexico viruses. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 6:142–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kou B, Crawford SE, Ajami NJ, Czakó R, Neill FH, Tanaka TN, Kitamoto N, Palzkill TG, Estes MK, Atmar RL. 2015. Characterization of cross-reactive norovirus-specific monoclonal antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol 22:160–167. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00519-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka T, Kitamoto N, Jiang X, Estes MK. 2006. High efficiency cross-reactive monoclonal antibody production by oral immunization with recombinant Norwalk virus-like particles. Microbiol Immunol 50:883–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.da Silva AK, Kavanagh OV, Estes MK, Elimelech M. 2011. Adsorption and aggregation properties of norovirus GI and GII virus-like particles demonstrate differing responses to solution chemistry. Environ Sci Technol 45:520–526. doi: 10.1021/es102368d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansman GS, Natori K, Shirato-Horikoshi H, Ogawa S, Oka T, Katayama K, Tanaka T, Miyoshi T, Sakae K, Kobayashi S, Shinohara M, Uchida K, Sakurai N, Shinozaki K, Okada M, Seto Y, Kamata K, Nagata N, Tanaka K, Miyamura T, Takeda N. 2006. Genetic and antigenic diversity among noroviruses. J Gen Virol 87:909–919. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Zhou R, Tian X, Li H, Zhou Z. 2010. Characterization of a cross-reactive monoclonal antibody against norovirus genogroups I, II, III and V. Virus Res 151:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiota T, Okame M, Takanashi S, Khamrin P, Takagi M, Satou K, Masuoka Y, Yagyu F, Shimizu Y, Kohno H, Mizuguchi M, Okitsu S, Ushijima H. 2007. Characterization of a broadly reactive monoclonal antibody against norovirus genogroups I and II: recognition of a novel conformational epitope. J Virol 81:12298–12306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00891-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ambert-Balay K, Pothier P. 2013. Evaluation of 4 immunochromatographic tests for rapid detection of norovirus in faecal samples. J Clin Virol 56:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2001. Diagnosis of noncultivatable gastroenteritis viruses, the human caliciviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:15–37. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.15-37.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirby A, Gurgel RQ, Dove W, Vieira SC, Cunliffe NA, Cuevas LE. 2010. An evaluation of the RIDASCREEN and IDEIA enzyme immunoassays and the RIDAQUICK immunochromatographic test for the detection of norovirus in faecal specimens. J Clin Virol 49:254–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morillo SG, Luchs A, Cilli A, Ribeiro CD, Calux SJ, Carmona RC, Timenetsky MC. 2011. Norovirus 3rd generation kit: an improvement for rapid diagnosis of sporadic gastroenteritis cases and valuable for outbreak detection. J Virol Methods 173:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Debbink K, Lindesmith LC, Ferris MT, Swanstom J, Beltramello M, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Baric RS. 2014. Within host evolution results in antigenically distinct GII.4 noroviruses. J Virol 88:7244–7255. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00203-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, Cannon JL, Zheng DP, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2008. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med 5:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Baric RS. 2011. Norovirus GII.4 strain antigenic variation. J Virol 85:231–242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01364-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]