Abstract

Background

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) is the most frequent and severe complication in patients receiving multiple blood transfusions. Current pathogenic concepts hold that proinflammatory mediators present in transfused blood products are responsible for the initiation of TRALI, but the identity of the critical effector molecules is yet to be determined. We hypothesize that mtDNA damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are present in blood transfusion products, which may be important in the initiation of TRALI. Methods: DNA was extracted from consecutive samples of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets procured from the local blood bank. Quantitative realtime polymerase chain reaction was used to quantify ≈ 200 bp sequences from the COX1, ND1, ND6, and D-loop regions of the mitochondrial genome.

Results

A range of mtDNA DAMPs were detected in all blood components measured, with FFP displaying the largest variation.

Conclusions

We conclude that mtDNA DAMPs are present in packed red blood cells, FFP, and platelets. These observations provide proof of the concept that mtDNA DAMPs may be mediators of TRALI. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis and to determine the origin of mtDNA DAMPs in transfused blood.

Keywords: TRALI, Transfusion-related acute lung injury, Mitochondria, ARDS, Transfusion Damage-associated molecular patterns, DAMP

1. Introduction

The diagnosis of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) has recently expanded to include a delayed presentation that occurs specifically in critically ill or injured patients [1] and is characterized by a rapid evolution of acute respiratory distress syndrome and a markedly higher mortality than conventional TRALI. Despite numerous previous studies, pathophysiologic mechanisms of TRALI remain poorly understood, and consequently, treatment is nonspecific and supportive.

For many years, TRALI was attributed to leukocyte antibodies in the donor blood directed against human leukocyte antigens and human neutrophil alloantigens in the recipient. However, this idea remains hotly debated because only a small proportion of donor plasma contained detectable anti-granulocyte or anti–human leukocyte antigen class I or II reactivity [2]; no clear relation between the presence of antigens or alloantigens in transfusion products and the occurrence of TRALI has been identified to date. Still, the notion that critical mediators are present in transfused blood products remains appealing in light of the direct correlation between the occurrence of lung injury and the number of transfusions and/or the storage life of the transfused products [2].

In an extension of this “mediator concept,” prior studies have found that proinflammatory mitochondrial (mt) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (mtDNA) fragments and mtDNA-associated proteins, are released into the circulation of severely injured patients [3,4]. Furthermore, we have previously noted that the abundance of mtDNA DAMPs predicts the occurrence of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and mortality [4]. Studies in cell culture, whole organ, and intact animal models show that mtDNA DAMPs cause endothelial injury and pulmonary edema [3,5,6]. We therefore hypothesized that as a potential effector of TRALI, mtDNA DAMPs would be present in blood transfusion products.

2. Methods

Consecutive samples of available blood components—fresh frozen plasma (FFP), platelets, and leukoreduced packed red blood cells (LR-PRBCs) were collected from the blood bank at the University of South Alabama Medical Center. This included the following quantity of samples from transfusion products: 11 LR-PRBC, 14 FFP, and 5 platelets. The FFP and platelet products were not leukoreduced. Each sample was taken from segments of each blood component set aside during the procurement process for testing purposes. Samples were centrifuged within 1 h of collection at 1200 RCF for 25 min at 21°C, and 200 μL of the plasma fraction was decanted and processed using the Qiagen DNEasy kit to isolate DNA (Qiagen, Inc, Valencia, CA). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, using USB VeriQuest Fast SYBR Green qPRC Master Mix (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) and the manufacturer's protocol, was applied to quantify selected ≈ 200 bp sequences corresponding to the COX1, ND1, ND6, and D-Loop mitochondrial genomic regions as previously described by our group [7,8]. The relative abundances of plasma mtDNA DAMPs were measured in threshold cycles (Tc) and converted to the amount of fold increase from the negative control.

3. Results

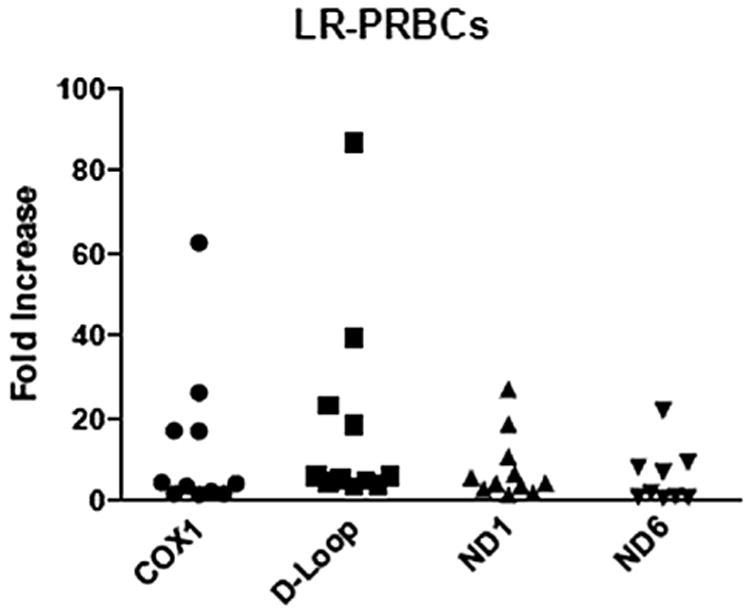

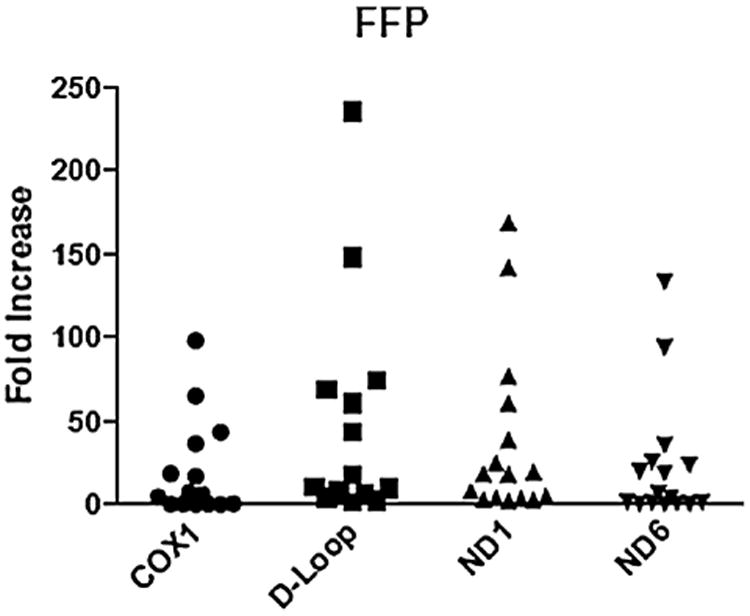

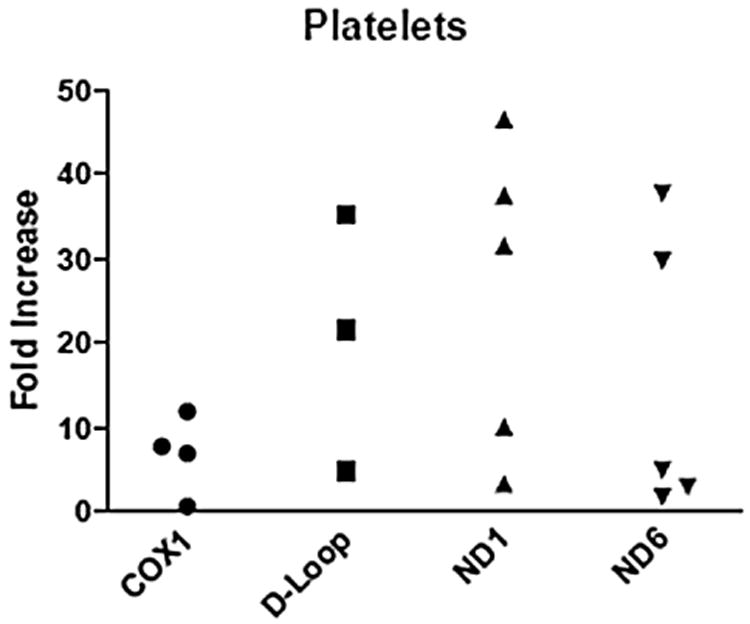

Samples from LR-PRBC (n = 11), FFP (n = 16), and platelets (n = 5) were analyzed for mtDNA sequences previously mentioned using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. A range of mtDNA DAMPs were detected in all blood components measured, with FFP displaying the largest variation. The amount of mtDNA measured from LR-PRBC ranged from 0.8- to 87-fold increase from the negative control (COX1 = 1.9–62.7, D-LOOP = 3.8–86.8, ND1 = 1.7–27.1, and ND6 = 0.8–22; Fig. 1). The amount of mtDNA measured from FFP ranged from 0.4- 235.6-fold increase from the negative control (COX1 = 0.4–98.4, D-LOOP = 1.9–235.6, ND1 = 2.6–168.9, and ND6 = 0.8–133.4; Fig. 2). The amount of mtDNA measured from platelets ranged from 0.7- 46.5- fold increase from the negative control (COX1 = 0.7–12, D-LOOP = 5–35.3, ND1 = 3.4–46.5, and ND6 = 1.9–37.8; Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Consecutive samples from leukocyte-reduced PRBCs reveal varying amounts of mtDNA fragments. Each sample is depicted as a single point and expressed as the fold increase from the negative control.

Fig. 2.

Consecutive samples from non–leukocyte-reduced FFP reveal varying amounts of mtDNA fragments. Each sample is depicted as a single point and expressed as the fold increase from the negative control.

Fig. 3.

Consecutive samples from non–leukocyte-reduced platelets reveal varying amounts of mtDNA fragments. Each sample is depicted as a single point and expressed as the fold increase from the negative control.

4. Discussion

Despite its recognition as a discrete syndrome many years ago, TRALI remains a common and vexing clinical problem. Effective therapy is complicated not only by a lack of understanding of its pathophysiologic mechanisms but also by the fact that TRALI probably exists in at least two clinical phenotypes. Conventional TRALI occurs within 6 h of administration of blood products, is comparatively rare, and has a low mortality. However, TRALI in the setting of trauma or critical illness (i.e., following multiple transfusions) occurs later—after as long as 72 h—and has a much higher incidence and mortality rate [1]. Regardless of the clinical presentation, TRALI has emerged as the leading cause of death in repeatedly transfused patients [9].

Our laboratory and others have previously established that exogenous administration of mtDNA DAMPs in isolated rat lungs [3,10,11] recapitulate the clinical phenotype of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Interestingly, this pulmonary dysfunction is abrogated by the simultaneous administration of a toll-like receptor-9 receptor blocker [10]. Furthermore, circulating mtDNA DAMP levels are predictive of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death in severely injured trauma patients [4]. Therefore, the exogenous intravenous administration of mtDNA DAMPs to patients would be expected to cause some degree of lung dysfunction via activation of the innate immune system. It is appropriate to note that detection of mtDNA fragments at a molecular level within transfusion products does not conclusively prove that the mtDNA fragments are biologically active, nor does it provide insight into their origin. However, as a first step to provide proof of concept that mtDNA DAMPs may be a key mediator in the development of delayed TRALI, the purpose of this study was to determine if mtDNA DAMPs are indeed present within transfused blood products.

This study did reveal that mtDNA fragments are present, in variable amounts, within all types of blood components examined. As expected, higher amounts were present within units of FFP and platelets, given that mammalian red blood cells lack mitochondria. Although the PRBCs examined were leukocyte reduced, residual mitochondria-containing cells may account for the detected mtDNA. Alternately, the handling and processing of whole blood to isolate PRBCs may mobilize mtDNA DAMPs into plasma, which remains in the final unit. Certainly, platelets themselves contain mitochondria, as do the variable amounts of leukocytes within platelet transfusions. FFP also contains variable cellular components, and mtDNA DAMPs mobilized during processing would accumulate in the plasma fraction. This may provide some insight into the discrepancy between the amounts of mtDNA detected in the different components.

5. Conclusions

We conclude that mtDNA DAMPs are present in PRBCs, FFP, and platelets. These observations provide proof of concept that mtDNA DAMPs may be mediators of the delayed phenotype of TRALI that occurs after multiple transfusions. Further studies are needed to determine their activity and the origin of mtDNA DAMPs within transfused blood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL058234, R01 HL113614), American Heart Association (14CRP19010032 and 13POST14780019), and the American College of Surgeons (Clowes Award).

Footnotes

Authors' contributions: Y.-L.L., M.N.G., and J.D.S. contributed to the study design. Y.-L.L. and M.B.K. did the polymerase chain reaction. Y.-L.L., M.B.K., and J.D.S. did the data collection. Y.-L.L. did the statistical analysis. Y.-L.L. and J.D.S. contributed to the article development. M.N.G., R.P.G., S.B.B., and M.A.F. did the article revisions. J.D.S. is the principal investigator. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data.

Dr Lee gave an oral presentation of this article (ASC20140386) at the ninth Annual Academic Surgical Congress on February 4, 2014, in San Diego, California.

Disclosure: The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in the article

References

- 1.Marik PE, Corwin HL. Acute lung injury following blood transfusion: expanding the definition. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3080. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silliman CC, Boshkov LK, Mehdizadehkashi Z, et al. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: epidemiology and a prospective analysis of etiologic factors. Blood. 2003;101:454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simmons J, Lee YL, Mulekar S, et al. Elevated levels of plasma mitochondrial DNA DAMPs are linked to clinical outcome in severely injured human subjects. Ann Surg. 2013;258:591. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a4ea46. discussion 596-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaung WW, Wu R, Ji Y, Dong W, Wang P. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is a proinflammatory mediator in hemorrhagic shock. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:199. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun S, Sursal T, Adibnia Y, et al. Mitochondrial DAMPs increase endothelial permeability through neutrophil dependent and independent pathways. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Mehdi AB, Pastukh VM, Swiger BM, et al. Perinuclear mitochondrial clustering creates an oxidant-rich nuclear domain required for hypoxia-induced transcription. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra47. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastukh VM, Zhang L, Ruchko MV, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in lung tissue from patients with COPD is clustered in functionally significant sequences. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:209. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S15922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saidenberg E, Petraszko T, Semple E, Branch DR. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): a Canadian blood services research and development symposium. Transfus Med Rev. 2010;24:305. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill JK, Obiako B, Gorodnya O, et al. A positive feedback cycle involving oxidative mitochondrial (mt) DNA damage and mtDNA damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) contributes to bacteria-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction in isolated rat lungs. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A4978. ABSTRACT. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouteau JM, Obiako B, Gorodnya OM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA integrity may be a determinant of endothelial barrier properties in oxidant-challenged rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L892. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00210.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]