Abstract

Dysregulation of the Hedgehog (Hh)-Gli signaling pathway is implicated in a variety of human cancers, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), medulloblastoma (MB), and embryonal rhabdhomyosarcoma (eRMS), three principle tumors associated with human Gorlin syndrome. However, the cellular origins of these tumors, including eRMS, remain poorly understood. In this study, we explore the cell populations that give rise to Hh-related tumors by specifically activating Smoothened (Smo) in both Hh-producing and -responsive cell lineages in postnatal mice. Interestingly, we find that unlike BCC and MB, eRMS originates from the stem/progenitor populations that do not normally receive active Hh signaling. Furthermore, we find that the myogenic lineage in postnatal mice is largely Hh quiescent and that Pax7-expressing muscle satellite cells are not able to give rise to eRMS upon Smo or Gli1/2 over-activation in vivo, suggesting that Hh-induced skeletal muscle eRMS arises from Hh/Gli quiescent non-myogenic cells. In addition, using the Gli1 null allele and a Gli3 repressor allele, we demonstrate the genetic requirement for Gli proteins in Hh-induced eRMS formation and provide molecular evidence for the involvement of SoxC factors in Hh-dependent eRMS cell survival and differentiation.

Introduction

The mammalian Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is involved in a variety of developmental and tumorigenic processes through regulation of cell proliferation, survival and differentiation [1-3]. In mammals, Hh ligands bind to the receptor, Patched1 (Ptch1), resulting in relieving inhibition of a seven-transmembrane protein, Smoothened (Smo). Activated Smo signals through an intracellular pathway to control the activities of the Gli family transcription factors, including Gli1, Gli2 and Gli3, which collectively regulate the transcription of downstream target genes[1, 4-7].

The first evidence linking Hh pathway activity to human cancer was the identification of germline mutations of Ptch1 in Gorlin syndrome, an autosomal disease associated with an increased incidence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), medulloblastoma (MB), and rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) [8-10]. Studies using genetically modified mouse models also established a clear link between abnormal Hh activity and development of these tumor types[11-18]. MB is the most common childhood brain tumor, and Hh-related MB is likely derived from the committed cerebellar granule neuron precursors (CGNPs)[18-22]. BCC is believed to arise from the skin epidermis, although it is still under debate whether it is derived from the interfollicular epidermis or from hair follicle stem cells [23-26]. Hh/Gli dysregulation is also associated with the genesis of embryonal RMS (eRMS), the major subtype of the most common soft tissue sarcoma in children[27-30]. Amplification or losses of the chromosomal regions containing genes for Hh pathway components, including Gli1, Ptch1 and Sufu, in a significant portion of human eRMS[31-34]. Furthermore, Hh pathway activation has been shown in the majority of sporadic eRMS cases and confers a poor prognosis in patients with these tumors[34, 35]. However, the exact cellular origin of eRMS and how Hh/Gli dysregulation contributes to eRMS formation remains poorly characterized.

Our previous study established a robust mouse model that mimics Hh-induced sporadic tumorigenesis through postnatal inducible Smo activation[17]. This model provides a genetic platform to study Hh-related eRMS with 100% penetrance. However, the ubiquitous nature of the CAGGSCreER line used in that study prevents further analysis of tumor cellular origins. Thus, in the current study we specifically activated Smo in postnatal Hh-expressing or -responsive lineages, and showed that BCC and medulloblastoma could be generated from the Hh-responsive progenitor cells within the hair follicle and developing cerebellum. However, we found that eRMS did not arise from either Hh-expressing or Hh-responsive populations. Genetic analysis of postnatal myogenic lineages revealed that the Hh pathway was not active in postnatal myogenesis. Using our recently established Rosa26 Gli1 and Gli2 conditional alleles, we further showed that neither Smo nor Gli1/2 activation in postnatal Pax7+ muscle stem cells was sufficient to drive eRMS formation, arguing for a cell of origin in Hh/Gli-quiescent non-myogenic stem/progenitor populations. Moreover, we presented evidence for downstream involvement of Gli1-independent and Sox4/11-dependent tumor cell survival and differentiation of Hh-induced eRMS cells.

Results

Constitutive Smo activation in Shh-expressing and -responsive lineages in postnatal mice

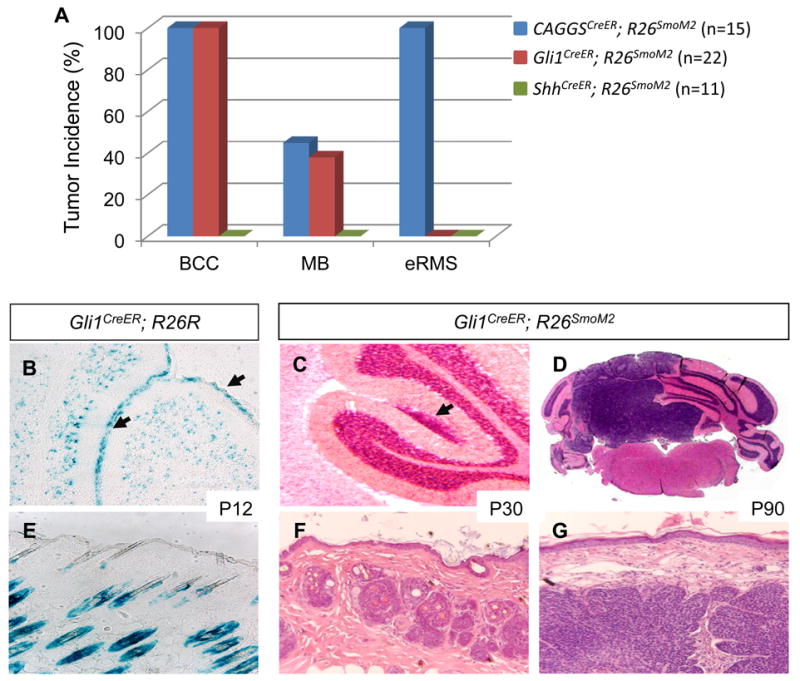

In the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 model[17], up-regulation of the Hh pathway is achieved by conditionally regulated expression of an activated allele of Smo (R26SmoM2)[17] using global postnatal induction of a ubiquitously expressed inducible Cre transgene (CAGGSCreER) [36]. SmoM2 encodes an activated allele of Smo previously identified in human BCC, in which a point mutation in the 7th transmembrane domain results in ligand-independent signaling activation[14]. Following a single dose of tamoxifen injection at postnatal day 10 (P10), 40% of the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice developed medulloblastoma and all of the mice displayed BCC and eRMS within 4 months (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Tumorigenesis in CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2, Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 and ShhCreER;R26SmoM2 mice.

(A) Distinct tumor spectrums in CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2, Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 and ShhCreER;R26SmoM2 mice. (B) β-galactosidase staining of Gli1-expressing cells in the developing cerebellum of Gli1CreER;R26R mice at postnatal day 12 (P12) after tamoxifen injection at postnatal day 10 (P10). Arrows indicate positively stained cells within the external granule layer. (C, D) H&E staining illustrating medulloblastoma development in the cerebellum of Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice at postnatal day 30 (P30) and day 90 (P90). Arrow indicates early lesion detected at P30. (E) β-galactosidase staining of the skin epithelium of Gli1CreER;R26R mice at P12 after tamoxifen injection at P10. Note that β-gal cells are exclusively located in the hair follicles. (F, G) H&E staining illustrating the formation of BCC in Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice at P30 and P90.

To further characterize the originating cell populations for these tumors, we used two inducible Cre alleles, ShhCreER [37] and Gli1CreER [38]. ShhCreER has a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (CreERT2) targeted into the Shh locus under the control of the endogenous Shh promoter[37]. We first generated ShhCreER;R26SmoM2 mice that exhibited constitutive Smo activation in Shh ligand-expressing cell lineages following tamoxifen injection at P10, the same time point at which SmoM2 was activated in the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice[17]. Interestingly, we did not detect BCC, MB and eRMS formation in ShhCreER;R26SmoM2 mice up to 10 months of age (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous reports that MB and BCC are probably not derived from Shh-expressing progenitors[18, 23], our results suggest that eRMS also arises from a Shh independent lineage and that autocrine Hh regulation is not likely involved in initiation of these Gorlin tumors.

The inducible Gli1CreER allele contains CreERT2 targeted into the endogenous Gli1 locus[38]. Recent studies have established that Hh activity is both necessary and sufficient for Gli1 transcription and that Gli1 expression provides a faithful and sensitive readout of the Hh signaling activity[38-42]. Therefore, we generated Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice to address whether constitutive pathway activation in Gli1-expressing cells and their descendents is able to drive tumor formation. Following tamoxifen injection at P10, the Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice developed MB (36%) and BCC (100%) at an incidence comparable to the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 model (Fig. 1A). However, in contrast to the 100% penetrance seen in CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice at 4 months of age, no RMS was detected in the Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice up to 12 months of age (Fig. 1A). These unique tumor spectra suggest that, unlike BCC and MB, eRMS does not originate from Hh-responsive cells, but rather from cell populations that are not normally undergoing active Hh signaling.

SmoM2 activation in Gli1-expressing cerebellar and hair follicle progenitor cells

To further characterize Hh-responsive populations in postnatal mice, we crossed Gli1CreER to the Rosa26 reporter strain, R26R [43]. We examined Gli1-expressing cells at postnatal day 12 (P12) after tamoxifen injection at P10. Consistent with previous reports[18-21], we found that Gli1 was highly expressed in the CGNPs in the developing cerebellum (Fig. 1B). We also detected a precursor lesion in all Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice (n=9) examined at postnatal day 30 (P30). These lesions were often located at the surface of the cerebellum and highly proliferative (Fig. 1C and Supplemental figure 1A), similar to the pre-neoplastic lesions described in Ptch1+/- mice[21]. Subsequently, a portion of these lesions gave rise to MB (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, we found that SmoM2 activation in Gli1+ postnatal neural stem cell populations in the forebrain did not lead to MB or glioma formation (Supplemental figure 1B), supporting the idea that Hh-induced MB arise from CGNPs [18]. In the postnatal skin, Gli1-expressing cells were detected within the hair follicle and we found no evidence of a Gli1-expressing lineage in the normal interfollicular epidermal epithelium (Fig. 1E). Constitutive SmoM2 expression in these Hh-responsive stem/progenitor cells induced BCC formation as early as P30 in the Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice (Fig. 1F and G), suggesting that the Hh responsive stem/progenitor cells within the hair follicular epithelium are possible origins of BCC.

Hh pathway activity in postnatal muscle

Our results from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 and Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice suggest a distinct cellular origin of eRMS from Hh quiescent cells. eRMS is generally thought to arise from the skeletal muscle lineage[30, 44-46]. Thus, we examined the Hh signaling status in wild type muscle and analyzed the fate of Hh-responsive cells during normal postnatal muscle growth and differentiation.

Following tamoxifen injection at P10, we analyzed the skeletal muscle of the Gli1CreER;R26R mice at P12 and P90. We did not detect any β-galactosidase-positive myofibers at either time point (Fig. 2A). Although the majority of the muscle cells are Hh pathway-negative, we did notice that a very small subset of cells located among the muscle fibers were positively labeled (Fig. 2A). To further characterize these cells derived from the Hh-responsive lineage, we performed immunostaining of laminin and β-galactosidase. Interestingly, these β-galactosidase positive cells were exclusively located in the interstitial regions outside the basal lamina (Fig. 2B-D). It suggests that they are unlikely to be muscle satellite cells, the postnatal myogenic stem cell population responsible for muscle cell growth and differentiation, as satellite cells and their descendent myoprogenitors are normally located underneath the basal lamina. Further analysis showed that these β-galactosidase-positive cells were largely Sca1+ (Fig. 2E-G), suggesting the association with the hematopoietic, rather than the myogenic lineage. Further, our Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 results clearly indicate that these Sca1+ cells are not the origin of Hh-related eRMS (Fig. 1A). Together, our analyses suggest that Hh pathway is largely quiescent in myogenic stem/progenitor cells during postnatal myogenesis.

Figure 2. Hh signaling in postnatal skeletal myogenesis.

(A) β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining of hindlimb skeletal muscle from Gli1CreER;R26R mice at P90 following tamoxifen injection at P10. (B-D) β-gal positive cells are located in the interstitial regions outside the basal lamina of myofibers. Arrows indicate β-gal positive cells. DAPI staining delineates the nuclei. (C-G) Co-expression of Sca1 and β-gal in a subset of Sca1 positive cells within skeletal muscle from Gli1CreER;R26R mice. Arrows indicate the cells expressing both β-gal and Sca-1.

Hh activation in juvenile muscle stem/progenitors in vitro

To further examine Hh signaling activity in postnatal muscle stem/progenitor cells, we isolated primary myogenic cells from the wild type mouse hindlimb muscle at P10, a time point that has been used in our tamoxifen-induced tumor models (Fig. 1). The isolated juvenile myogenic cells were enriched with satellite cells and early myogenic progenitors, as qPCR analysis showed significantly elevated expression of satellite cell markers (Pax7 and Myf5) and early myogenic markers (MyoD) in these cells compared with wild type muscle (Fig. 3A). Consistent with our in vivo lineage analysis (Fig. 2), these myogenic progenitor cells did not have active Hh signaling transduction, as measured by qPCR analysis of Ptch1 and Hip1, two known Hh targets that were highly expressed in eRMS cells isolated from CAGGS-CreER;R26-SmoM2 mice (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. SmoM2 and Gli1/2 activation in muscle stem/progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Expression of Hh pathway target genes, Ptch1 and HIP1, and myogenic markers, Pax7, Myf5 and MyoD, in hindlimb skeletal muscle, freshly isolated myogenic progenitors from P10 wild type mice, and eRMS cells from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice, measured by qPCR analysis. (B) 4OH-TM-induced SmoM2 expression in myogenic progenitor cells isolated from P10 CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice. SmoM2/YFP fusion protein was detected by an anti-GFP antibody. (C) Ptch1, Gli1 and HIP1 expression, measured by qPCR, in myogenic progenitors isolated CAGGSCreER; R26SmoM2 mice and treated with or without 4OH-TM for 2 days. (D) Cell proliferation of juvenile myogenic progenitors with or without 4OH-TM treatment in growth media. (E) Apoptosis, measured by caspase 3/7 activity, in juvenile myogenic progenitors with or without 4OH-TM treatment in differentiation media. (F) SmoM2 activation in myoprogenitor cells inhibits differentiation in vitro, measured by MyHC expression. (G) Schematic representation of the Rosa26 knock-in R26Gli2ΔN allele. A cDNA fragment encoding Gli2ΔN with a N-terminal 3XFlag tag was inserted into the Rosa26 locus following the LoxP-Neo-4xpA-LoxP stop cassette. (H) Gli2ΔN expression in myogenic progenitor cells isolated from tamoxifen (TM) treated CAGGSCreER;R26Gli2ΔN mice. Gli2ΔN/Flag fusion protein was detected by an anti-Flag antibody. (I) SmoM2, Gli1 and Gli2 activation in muscle satellite cells in vivo fail to drive eRMS formation in Pax7CreER;R26SmoM2, Pax7CreER;R26Gli1, Pax7CreER;R26Gli2ΔN and Pax7CreER;R26Gli1;R26Gli2ΔN mice.

We next examined whether these cells are capable of responding to Hh activation. Juvenile myogenic cells isolated from the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice were treated with 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4OH-TM) to induce SmoM2 expression (Fig. 3B). Significant up-regulation of the Hh target genes, Ptch1, Gli1 and Hip1, was detected after 4OH-TM treatment (Fig. 3C), indicating Hh pathway activation. However, we found that ectopic expression of SmoM2 did not promote proliferation of these primary cells, as measured by MTT-based assay and Ki67 staining (Fig. 3D and data not shown). Primary myogenic progenitors undergo apoptosis under differentiation conditions[47, 48]. Interestingly, SmoM2 activation partially protected the cells from apoptosis when switching to the differentiation media or after exposure to apoptotic stimulus cycloheximide (CHX). SmoM2 expression led to lower caspase-3/7 activity in primary cells with tamoxifen treatment after serum deprivation or CHX treatment (Fig. 3E, and Supplemental fig. 2A). Next, we examined whether myogenic differentiation of these progenitor cells can be regulated by Hh pathway over-activation. We found that SmoM2 impaired cell differentiation, as assessed by the expression of the skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain (MyHC) in primary cells grown in differentiation media for 6 days (Fig. 3F, and Supplemental fig. 2B-D). Collectively, these data suggested that juvenile myogenic progenitor cells are normally Hh signaling-quiescent, but are capable of responding to Hh up-regulation, and that cell-autonomous SmoM2 activation promotes cell survival and differentiation in vitro.

SmoM2 and Gli1/2 activation in postnatal muscle satellite cells in vivo

To examine the in vovo effect of Hh/Gli on postnatal muscle stem cells, we crossed the inducible satellite cell Cre driver, Pax7CreER [49], to R26SmoM2, R26Gli1 [50] and R26Gli2ΔN mice. R26Gli2ΔN is a Rosa26 conditional knock-in allele of Gli2 recently generated in the lab that enables Cre-dependent expression of a constitutively active N-terminally truncated form of Gli2 fused with a N-terminal 3XFlag tag (Fig. 3G). These genetic approaches allow us to achieve pathway activation at both the cell surface Smo level and downstream Gli level, because Hh ligand/receptor-independent Gli1/2 regulation is also involved in tumorigenesis[6, 7, 10].

Pax7CreER;R26SmoM2, Pax7CreER;R26Gli1, Pax7CreER;R26Gli2ΔN and Pax7CreER;R26Gli1;R26Gli2ΔN mice were generated and administrated with tamoxifen at postnatal day 10 (P10). The expression in SmoM2-YFP, Gli1-Flag and Gli2ΔN-Flag in isolated myogenic cells from tamoxifen treated animals was detected by immunoblot (Fig. 3H and data not shown). Interestingly, in contrast to the widespread formation of eRMSs in the limbs and the trunk region in all CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice, none of the Pax7CreER;R26SmoM2, Pax7CreER;R26Gli1, Pax7CreER;R26Gli2ΔN and Pax7CreER;R26Gli1;R26Gli2ΔN mice treated with tamoxifen developed eRMS by 360 days (Fig. 3I), suggesting that Hh/Gli activation in vivo in postnatal satellite cells is not sufficient to drive eRMS formation. More importantly, it suggests that eRMSs developed in the skeletal muscle of the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice may arise from a Hh/Gli-quiescent non-myogenic cellular origin.

Genetic requirement of Gli proteins in Hh-induced RMS

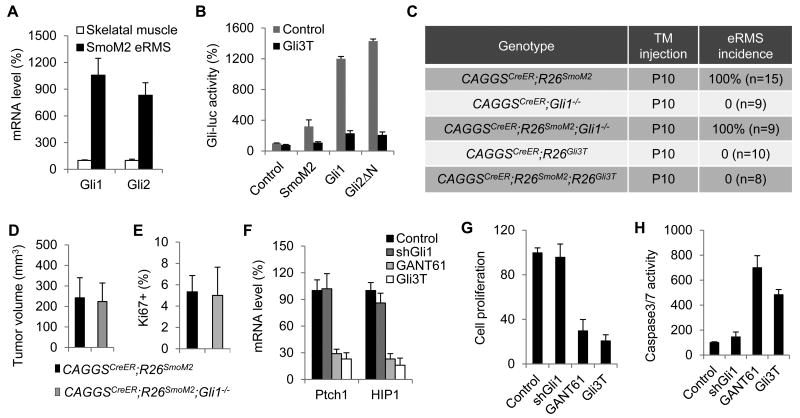

Among the three mammalian Gli proteins, Gli1 and Gli2 mainly function as transcriptional activator, while Gli3 largely acts as a transcriptional repressor [6, 7]. Gli1 itself, a transcriptional target of Hh signaling, is dispensable for normal development and homeostasis but likely involved in tumorigenesis[6, 7]. A previous report showed that removing Gli1 activity in the Ptch1+/- medulloblastoma model is able to partially block tumor formation[51]. Our transcriptional profiling and expression analysis showed that both Gli1 and Gli2 are up-regulated in SmoM2-induced eRMS ([17] and Fig. 4A), indicating a broad involvement of Gli activity in eRMS. However, the requirement of different Gli proteins in eRMS formation has not been examined.

Figure 4. Gli requirement in Hh-induced eRMS.

(A) Gli1 and Gli2 up-regulatin in eRMS cells from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice, measured by qPCR analysis. (B) Gli3T inhibits SmoM2-, Gli1- and Gli2ΔN-induced transcription in NIH3T3 cells, measured by a luciferase reporter assay. (C) eRMS genesis in CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice with either Gli1 removal or Gli3T expression. (D) Average tumor volume of eRMSs dissected from the hindlimbs of CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 and CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2;Gli1-/- mice. (E) The percentage of Ki67+ cells in eRMSs from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 and CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2;Gli1-/- mice. (F) Expression of the Hh targets, Ptch1 and HIP1, in isolated eRMS cells with shGli1 or Gli3T expression, or GANT61 treatment. (G, H) Cell proliferation (G) and caspase3/7 activity (H) in isolated eRMS cells with shGli1 or Gli3T expression, or GANT61 treatment.

To address this question, we utilized the Gli1 null allele [40] and a Gli3 transcriptional repressor allele, R26Gli3T [52]. Gli3T lacks the C-terminal transcriptional activation domain and functions as a constitutive transcriptional repressor [53], and was able to effectively inhibit SmoM2-, Gli1-, and Gli2-induced transcriptional activity, as determined by a Gli-luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 4B). We generated CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2;Gli1-/- and CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2;R26Gli3T mice and monitored eRMS formation following tamoxifen injection at P10. We found that removing Gli1 activity did not significantly affect SmoM2-induced eRMS formation, as measured by tumor incidence, size and proliferation status (Fig. 4C-E). However, we found that inhibition of Gli-mediated transcription by Gli3T was able to completely block Hh-induced tumorigenesis, including eRMS (Fig. 4C). In contrast to 100% penetrance of eRMS formation in 4-months-old CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice after tamoxifen treatment (n=15), none of the CAGGSCreER;R26Smom2;R26Gli3T mice examined (n=8) developed eRMS at the age of 8 months (Fig. 4C). Histology analysis of the skeletal muscle of CAGGSCreER;R26Smom2;R26Gli3T mice also did not reveal early hyperproliferative lesions of eRMS (data not shown). These data demonstrate the genetic requirement of Gli activation in eRMS in vivo, but suggest that Gli1 is largely dispensable for SmoM2-induced eRMS formation.

To further examine Gli activity in eRMS cells, primary tumor cells isolated from the hindlimb eRMS of the CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice were infected with lentivirus expressing Gli3T or shRNAs against Gli1 (shGli1), or treated with GANT61, a small molecule Gli inhibitor that is capable of inhibiting both Gli1- and Gli2-mediated transcription [54]. Consistent with the in vivo tumorigenesis analysis, we found that Gli3T expression or GANT61 treatment, but not shGli1 expression, significantly inhibited Hh pathway activation, tumor cell proliferation and survival (Fig. 4F-H).

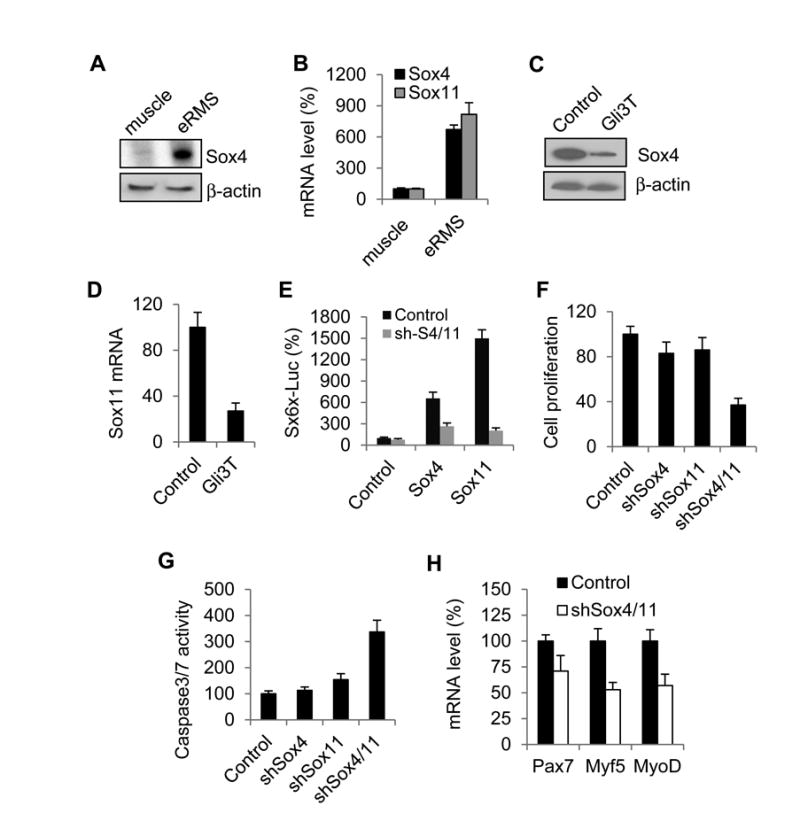

Sox4/11 involvement in Hh-dependent eRMS

The downstream molecular mechanism underlying Hh-Gli dysregulation in eRMS remains poorly understood. The SoxC transcription factors have been reported to play important roles in tumorigenesis in several cancer types[55-58], although it is not clear whether these factors are involved in eRMS. Interestingly, our previous gene expression profiling studies in CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice showed that Sox4 and Sox11, two closely related SoxC factors, were highly up-regulated in SmoM2-induced eRMS[17], which prompted us to examine whether Sox4/11 have an oncogenic role in Hh dependent eRMS cells.

Consistent with the expression profiling data, we found that Sox4 and Sox11 were highly expressed in SmoM2-induced eRMS cells, compared to the wild type skeletal muscle, as measured by immunoblot and qPCR analyses (Fig. 5A, B). Furthermore, lentiviral expression of Gli3T in these primary eRMS cells resulted in down-regulation of Sox4 and Sox11 expression (Fig. 5C, D), suggesting that Sox4/11 may act downstream of Hh signaling in eRMS. To explore their potential functional roles, we generated shRNAs against mouse Sox4 and Sox11. Knockdown of either Sox4 or Sox11 alone in these cultured eRMS cells had little or no effect (Fig. 5F, G), suggesting a possible functional redundancy between these two factors. However, the presence of shRNAs against both Sox4 and Sox11 was able to inhibit Sox4/11-induced transcription activation (Fig. 5E), blocked proliferation (Fig. 5F) and induced apoptosis (Fig. 5G) in the primary eRMS cells. Interestingly, we found that Sox4/11 knockdown also disrupted the differentiation program of eRMS cells. qPCR analysis showed that expression of the myogenic markers, including Pax7, Myf5 and MyoD, was down-regulated after Sox4/11 knockdown(Fig. 5H). Together, these data suggest that Sox4/11 proteins may play an important role downstream of Hh/Gli in regulation of eRMS cell proliferation, survival and differentiation.

Figure 5. Sox4/11 regulate eRMS cell proliferation, survival and differentiation.

(A, B) Sox4 and Sox11 expression in the wild type hindlimb skeletal muscle or SmoM2-induced eRMS cells, measured by immunoblot (A) and qPCR analysis (B) (C, D) Sox4 and Sox11 expression in isolated eRMS cells with and without Gli3T expression. (E) shRNAs again Sox4 and Sox11 (shSox4/11) effectively blocked Sox4 and Sox11-induced gene transcription in a luciferase reporter assay. (F) Sox4/11 knockdown inhibits eRMS cell proliferation. (G) Sox4/11 knockdown induces apoptosis in isolated eRMS cells, measured by caspase 3/7 activity. (H) qPCR analysis of transcription of the myogenic markers, Pax7, Myf5 and MyoD in cultured eRMS cells with Sox4/11 knockdown.

Discussion

BCC, MB and eRMS are three original tumors associated with the Gorlin syndrome and Hh pathway dysregulation. Our data here support the model that Shh-related MB originates from Gli1-expressing CGNPs [18]. The exact origin of BCC is still under debate. A recent study suggests that the hair follicle stem cell niche resists transformation by the Hh pathway [23, 24], while other studies using different transgenic models show that follicle stem cells can give rise to BCC[25, 26, 59]. Interestingly, a recent report shows that Gli1 is expressed in a distinct subpopulation of hair follicle bulge stem cells [42]. Our study using the Gli1CerER allele indicates that the Gli1+ follicular stem/progenitor cells are capable of generating BCC upon Smo activation.

eRMS is an aggressive muscle tumor, and its cellular origin remains elusive [30]. It was generally thought that eRMS arises from cells of the myogenic lineage, largely due to the expression of early or late myogenic markers, such as Pax7, MyoD and Myogenin. Indeed, recent studies showed that postnatal Pax7+ satellite cells or myogenic progenitor populations can give rise to RMS, including eRMS, upon deletion of the tumor suppressor p53 or activation of oncogenic Kras [45, 46]. However, eRMS initiating populations are likely heterogeneous. The drastic difference of eRMS incidence in our CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 and Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 models provides an interesting clue to the cellular origin of Hh-induced eRMS. It suggests that, unlike BCC and MB, the other two tumors associated with Gorlin syndrome, eRMS is instead derived from Hh/Gli-quiescent stem/progenitor cells. Our genetic fate-mapping experiments suggest that Hh signaling is quiescent during postnatal myogenesis and muscle satellite cells do not normally carry active Hh signaling, although they retain the capacity to respond to Hh over-activation. Further, our data demonstrated that neither SmoM2 expression nor downstream Gli1/2 activation in Pax7+ postnatal satellite cells is able to drive eRMS formation in vivo. Collectively, these experiments argue that Hh-induced postnatal eRMSs arise from Hh/Gli-quiescent non-myogenic populations. Our data are consistent with a recent report that SmoM2 expression from the adipocyte progenitors can give rise to a subset of eRMS [60]. Interestingly, in this aP2Cre;R26SmoM2 model, eRMS is only detected in the head and neck region [60], while in our CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 model, eRMS are predominantly located in the limbs and trunk region[17], pointing to a distinct, yet unidentified cell of origin for these eRMS.

The involvement of Hh/Gli signaling in eRMS development is multifaceted. It is likely that Hh over-activation in the non-myogenic progenitors, including those of the adipose lineage [60], may drive transdifferentiation into eRMS. Intriguingly, we found that, although Hh/Gli activation in juvenile satellite cells alone is not sufficient to induce eRMS in vivo, it can regulate the survival and differentiation of primary juvenile satellite cells in culture. We did not detect significant stimulation of cell proliferation by Hh, in contrast to a previous report for such effect on cultured adult satellite cells [61]. It is probably due to distinct characteristics between juvenile and adult satellite cells [49]. However, these results support the idea that Hh pathway may function as an oncogenic modifier in RMS arising from the myogenic lineage [46]. It was recently reported that heterogeneous deletion of Ptch1 in the p53 RMS mouse model shifts the tumor spectrum towards the eRMS type [46]. In addition to tumor initiation, Hh activity is also important for eRMS progress. Hh pathway activation is detected in the majority of sporadic eRMS cases [34, 62]. Our genetic study here demonstrated the in vivo requirement for Gli-mediated transcription in eRMS. However, it appears that Gli1 may not be critical for SmoM2-induced eRMS development, although Gli1 has been reported to play important roles in other Hh-related tumorigenic settings [6, 7, 51].

Our results revealed a novel molecular mechanism that involves the Sox4/11 factors downstream of Hh signaling in eRMS. SoxC transcription factors are essential for embryonic mesenchymal progenitor survival [63]. Sox4 or Sox11 up-regulation has also been implicated in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic malignancies [55-58, 64]. Our data are the first to link the SoxC factors to eRMS and Hh-dependent tumorigenesis. We showed here that the activities of Sox4 and Sox11 are critical for tumor cell proliferation and survival, and that these factors may also play a role in eRMS cell differentiation. It is worth noting that Hh signaling itself also regulates eRMS cell differentiation through direct interaction between Gli proteins and the myogenic transcription factor MyoD[65]. Clearly, further elucidation of the functional interplays among these critical pathways may lead to future design of more effective strategies for diagnosis and treatment of eRMS.

Methods

Mouse strains

CAGGSCreER, Gli1CreER, ShhCreER, Pax7CreER, R26R, R26SmoM2, R26Gli1 and R26Gli3T mice have been described before [17, 36-38, 43, 49, 50, 52]. To generate the R26Gli2ΔN allele, the cDNA encoding the N-terminally truncated activated form of Gli2 fused with a N-terminal 3X Flag tag was inserted into the shuttling vector pBigNeoT before cloned in pROSA-PAS to produce the final targeting construct for ES cell targeting. Mice used in this study were in a mixed genetic background, including 129/Sv and Swiss Webster as main components, and all mouse experiments were performed according to the guidelines of IACUC at University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Tamoxifen treatment, tissue collection and histology

Tamoxifen (Sigma) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma), and injected intraperitoneally at P10 in mice carrying inducible Cre alleles (1.5mg per 10g body weight). Tissues were harvested at different time points as indicated following injection and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight. The hindlimb eRMS tumors were dissected from 4-months-old CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 and CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2;Gli1-/- mice, and tumor volume was calculated as 0.5 × l × w2, with l indicating length and w indicating width. Paraffin sections (6 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard protocols.

β-galactosidase staining, immunefluorescence and immunoblotting

Frozen sections were cut at 12μm intervals and subjected to standard β-galactosidase staining. For immunofluorescence, sections were washed with PBS and incubated at 4°C overnight in primary antibodies: Laminin (1:200, Abcam), Sca-1 (1:200, BD Biosciences), β-galactosidase (1:1000, Abcam), Ki67 (1:500, Abcam), and MyHC (1:500). Alexa-Fluor fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used for detection. For immunoblotting, primary antibodies used were: β-actin (1:1000, Sigma), MyHC (1:3000, Sigma), Sox4 (1:600, Sigma) and GFP (1:5000, Abcam). HRP conjugated secondary antibodies used for detection were obtained from Jackson Laboratories.

Primary myogenic progenitor and eRMS cell isolation and culture

Isolation of primary myogenic progenitor cells from mouse hindlimb skeletal muscles at P10 was performed using a two-step protocol, including isolation of single muscle fibers, followed by releasing myoprogenitor cells from isolated fibers. Briefly, the hindlimb muscle was digested in 0.2% collagenase and incubated in shaking waterbath at 37 degree for 90 minutes. Heat polished glass Pasteur pipetters were then used to triturate and dissociate muscle into single fibers. After washing, a collagenase/dispase solution was used to purify myogenic progenitor cells from the fibers. The isolated cells were cultured in the growth media containing 20% FCS and 5ng/ml bFGF. To activate Hh/Smo signaling, fiber-associated myogenic cells isolated from the mice carrying the R26-SmoM2 alleles were treated with 1ug/ml 4OH-tamoxifen for 2 days. To isolate eRMS tumor cells, the hindlimb eRMS tumors from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice were dissected, minced, and digested in 0.5% Trypsin and 0.2% collagenase at 37°C with agitation. After 20 minutes, the digested material was filtered through a 105-μm nylon mesh, and freshly isolated eRMS cells were then cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and subjected to further analysis.

Cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation assays

For MTT-based cell proliferation assay, cells were seeded at a density of 6000 per well in a 96-well plate. After 5 mg/ml MTT treatment at 2, 4 and 6 days after seeding, cells were lysed in DMSO and absorbance was measured at 595 nm. For myogenic progenitor differentiation assay, the culture media was replaced with the differentiation media that contained 5% horse serum. The cells were harvested at day 0 (immediately before switching to the differentiation medium) and day 6 for western blotting or immunoflorescence analyses of MyHC expression. Apoptosis and caspase-3/7 activity was determined using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay system (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative RT-PCR

cDNA synthesis was conducted using Superscript II kit. Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR were: mouse Ptch1 (CTCTGGAGCAGATTTCCAAGG and TGCCGCAGTTCTTTTGAATG), GAPDH (AGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATGTC and GCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCT), Gli1 (GTCGGAAGTCCTATTCACGC and CAGTCTGCTCTCTTCCCTGC), Gli2 (gagccaccccagcgtagaca and gccccaggtcgcactctag), HIP1 (CCTGTCGAGGCTACTTTTCG and TCCATTGTGAGTCTGGGTCA), Pax7 (CCAAGATTCTGTGCCGATATCCGGA and AGCTGGTTAGCTCCTGCCTGCTAA), Myf5 (ACAGCAGCTTTGACAGCATC and AAGCAATCCAAGCTGGACAC), MyoD (GGAGGAGCACGCACACTTC and CGCTGTAATCCATCATGCCATCAGAGC), MyHC (ACAAGCTGCGGGTGAAGAGC and CAGGACAGTGACAAAGAACG), Sox4 (GCCTCCATCTTCGTACAACC and AGTGAAGCGCGTCTACCTGT), and Sox11 (ATCAAGCGGCCCATGAAC and TGCCCAGCCTCTTGGAGAT).

shRNA knockdown

Isolated eRMS cells or myogenic progenitor cells were infected with pGIPZ or pLKO-based lentiviruses encoding shRNAs targeting mouse Sox4 and Sox11 (GCCCGACATGCACAACGCCGAG and TGCGCCTCAAGCACATGGCTGA), Sox4 (TGGCTGACTACCCTGACTACAA and GCGCTCGATCGGGACCTGGATT), Sox11 (GTCCCTGTCGCTGGTGGATAAG and TGCAGACGACCTCATGTTCGAC), or Gli1 (CCTGTGTACCACATGACTCTA and CGACTTGAGCATTATGGACAA). Infected cells were selected in 5 μg/ml puromycin for 4 days.

Luciferase reporter analysis

NIH3T3 cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter constructs, Sx6X-Luc (gift of Dr. Michael Wegner, Universitat Erlangen-Nurnberg), GliBS-Luc (gift of Dr. H. Kondoh, Osaka University), and the expression vectors for Renila luciferase, SmoM2, Gli1, Gli2ΔN, Gli3T, Sox4 and Sox11. Luciferase assays were conducted 48 hours after transfection using the dual-luciferase reporter kit (Promega).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental figure 1. SmoM2 activation in postnatal brain. (A, B) Precursor lesions of MB in the cerebellum of Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice. (A) H&E staining and (B) Ki67 immunofluoresence staining of the early lesions detected in P30 cerebellum of Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice following tamoxifen injection at P10. Arrows indicates the locations of the precursor lesions. (C-G) Hh over-activation in postnatal neural stem cells is not sufficient to drive transformation. (C) β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles of the Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice at P90. (D, E) H&E staining of the subventricular zone in the forebrain of 8-months-old R26SmoM2 and Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice. (F, G) Ki67 immunostaining showing no difference of proliferation in the subventricular zones of R26SmoM2 and Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice.

Supplemental figure 2. SmoM2 activation regulates survival and differentiation of cultured juvenile myogenic progenitors in vitro. (A) Caspase 3/7 activity in isolated myogenic progenitor cells from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice with 4OH-TM treatment in the presence of apoptotic stimulus CHX. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of MyHC in isolated myogenic progenitor cells in growth medium and differentiation medium with or without 4OH-TM.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from American Cancer Society (120376-RSG-11-040-01-DDC), Charles H. Hood Foundation and Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research to JM. APM is supported by a grant from NIH (NS033642). The authors thank Drs. Michael Rudnicki (University of Ottawa) and Amy Wagers (Joslin Diabetes Center) for providing cell isolation protocols, Joe Vaughan and Zhiwei Pang for technical support, and members of the Mao lab for helpful discussion.

References

- 1.McMahon AP, Ingham PW, Tabin CJ. Developmental roles and clinical significance of hedgehog signaling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2003;53:1–114. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)53002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang J, Hui CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2008;15(6):801–12. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barakat MT, Humke EW, Scott MP. Learning from Jekyll to control Hyde: Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16(8):337–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lum L, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog response network: sensors, switches, and routers. Science. 2004;304(5678):1755–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper JE, Scott MP. Communicating with Hedgehogs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(4):306–17. doi: 10.1038/nrm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui CC, Angers S. Gli Proteins in Development and Disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:23.1–23.25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stecca B, Ruiz IAA. Context-dependent regulation of the GLI code in cancer by HEDGEHOG and non-HEDGEHOG signals. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2(2):84–95. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal-cell carcinoma syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987;66(2):98–113. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ. Targeting the Hedgehog pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(12):1026–33. doi: 10.1038/nrd2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teglund S, Toftgard R. Hedgehog beyond medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1805(2):181–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RL, et al. Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science. 1996;272(5268):1668–71. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn H, et al. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85(6):841–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oro AE, et al. Basal cell carcinomas in mice overexpressing sonic hedgehog. Science. 1997;276(5313):817–21. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie J, et al. Activating Smoothened mutations in sporadic basal-cell carcinoma. Nature. 1998;391(6662):90–2. doi: 10.1038/34201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aszterbaum M, et al. Ultraviolet and ionizing radiation enhance the growth of BCCs and trichoblastomas in patched heterozygous knockout mice. Nat Med. 1999;5(11):1285–91. doi: 10.1038/15242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grachtchouk M, et al. Basal cell carcinomas in mice overexpressing Gli2 in skin. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):216–7. doi: 10.1038/73417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao J, et al. A novel somatic mouse model to survey tumorigenic potential applied to the Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66(20):10171–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuller U, et al. Acquisition of granule neuron precursor identity is a critical determinant of progenitor cell competence to form Shh-induced medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(2):123–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Control of neuronal precursor proliferation in the cerebellum by Sonic Hedgehog. Neuron. 1999;22(1):103–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowitch DH, et al. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and inhibits differentiation of CNS precursor cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19(20):8954–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08954.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver TG, et al. Loss of patched and disruption of granule cell development in a pre-neoplastic stage of medulloblastoma. Development. 2005;132(10):2425–39. doi: 10.1242/dev.01793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson P, et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1095–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youssef KK, et al. Identification of the cell lineage at the origin of basal cell carcinoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(3):299–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridky TW, Khavari PA. The hair follicle bulge stem cell niche resists transformation by the hedgehog pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(4):292–4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grachtchouk M, et al. Basal cell carcinomas in mice arise from hair follicle stem cells and multiple epithelial progenitor populations. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(5):1768–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI46307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang GY, et al. Basal cell carcinomas arise from hair follicle stem cells in Ptch1(+/-) mice. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pappo AS. Rhabdomyosarcoma and other soft tissue sarcomas of childhood. Curr Opin Oncol. 1995;7(4):361–6. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merlino G, Helman LJ. Rhabdomyosarcoma--working out the pathways. Oncogene. 1999;18(38):5340–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breneman JC, et al. Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma--a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):78–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hettmer S, Wagers AJ. Muscling in: Uncovering the origins of rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Med. 2010;16(2):171–3. doi: 10.1038/nm0210-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts WM, et al. Amplification of the gli gene in childhood sarcomas. Cancer Res. 1989;49(19):5407–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridge JA, et al. Novel genomic imbalances in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma revealed by comparative genomic hybridization and fluorescence in situ hybridization: an intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27(4):337–44. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(200004)27:4<337::aid-gcc1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bridge JA, et al. Genomic gains and losses are similar in genetic and histologic subsets of rhabdomyosarcoma, whereas amplification predominates in embryonal with anaplasia and alveolar subtypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33(3):310–21. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tostar U, et al. Deregulation of the hedgehog signalling pathway: a possible role for the PTCH and SUFU genes in human rhabdomyoma and rhabdomyosarcoma development. J Pathol. 2006;208(1):17–25. doi: 10.1002/path.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zibat A, et al. Activation of the hedgehog pathway confers a poor prognosis in embryonal and fusion gene-negative alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2010;29(48):6323–30. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2002;244(2):305–18. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harfe BD, et al. Evidence for an expansion-based temporal Shh gradient in specifying vertebrate digit identities. Cell. 2004;118(4):517–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahn S, Joyner AL. Dynamic changes in the response of cells to positive hedgehog signaling during mouse limb patterning. Cell. 2004;118(4):505–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, et al. Gli1 is a target of Sonic hedgehog that induces ventral neural tube development. Development. 1997;124(13):2537–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bai CB, et al. Gli2, but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway. Development. 2002;129(20):4753–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahn S, Joyner AL. In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 2005;437(7060):894–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brownell I, et al. Nerve-derived sonic hedgehog defines a niche for hair follicle stem cells capable of becoming epidermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(5):552–65. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tiffin N, et al. PAX7 expression in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma suggests an origin in muscle satellite cells. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(2):327–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hettmer S, et al. Sarcomas induced in discrete subsets of prospectively isolated skeletal muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(50):20002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111733108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubin BP, et al. Evidence for an unanticipated relationship between undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(2):177–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asakura A, et al. Increased survival of muscle stem cells lacking the MyoD gene after transplantation into regenerating skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(42):16552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708145104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirai H, et al. MyoD regulates apoptosis of myoblasts through microRNA-mediated down-regulation of Pax3. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(2):347–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lepper C, Conway SJ, Fan CM. Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature. 2009;460(7255):627–31. doi: 10.1038/nature08209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vokes SA, et al. Genomic characterization of Gli-activator targets in sonic hedgehog-mediated neural patterning. Development. 2007;134(10):1977–89. doi: 10.1242/dev.001966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimura H, et al. Gli1 is important for medulloblastoma formation in Ptc1+/- mice. Oncogene. 2005;24(25):4026–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vokes SA, et al. A genome-scale analysis of the cis-regulatory circuitry underlying sonic hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian limb. Genes Dev. 2008;22(19):2651–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.1693008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang B, Fallon JF, Beachy PA. Hedgehog-regulated processing of Gli3 produces an anterior/posterior repressor gradient in the developing vertebrate limb. Cell. 2000;100(4):423–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lauth M, et al. Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(20):8455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brennan DJ, et al. The transcription factor Sox11 is a prognostic factor for improved recurrence-free survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liao YL, et al. Identification of SOX4 target genes using phylogenetic footprinting-based prediction from expression microarrays suggests that overexpression of SOX4 potentiates metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2008 doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu P, et al. Sex-determining region Y box 4 is a transforming oncogene in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4011–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medina PP, et al. The SRY-HMG box gene, SOX4, is a target of gene amplification at chromosome 6p in lung cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(7):1343–52. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kasper M, et al. Wounding enhances epidermal tumorigenesis by recruiting hair follicle keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(10):4099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014489108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hatley ME, et al. A mouse model of rhabdomyosarcoma originating from the adipocyte lineage. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(4):536–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koleva M, et al. Pleiotropic effects of sonic hedgehog on muscle satellite cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(16):1863–70. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tostar U, et al. Reduction of human embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma tumor growth by inhibition of the hedgehog signaling pathway. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(9):941–51. doi: 10.1177/1947601910385449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhattaram P, et al. Organogenesis relies on SoxC transcription factors for the survival of neural and mesenchymal progenitors. Nat Commun. 2010;1:9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee CJ, et al. Differential expression of SOX4 and SOX11 in medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2002;57(3):201–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1015773818302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerber AN, et al. The hedgehog regulated oncogenes Gli1 and Gli2 block myoblast differentiation by inhibiting MyoD-mediated transcriptional activation. Oncogene. 2007;26(8):1122–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figure 1. SmoM2 activation in postnatal brain. (A, B) Precursor lesions of MB in the cerebellum of Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice. (A) H&E staining and (B) Ki67 immunofluoresence staining of the early lesions detected in P30 cerebellum of Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice following tamoxifen injection at P10. Arrows indicates the locations of the precursor lesions. (C-G) Hh over-activation in postnatal neural stem cells is not sufficient to drive transformation. (C) β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles of the Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice at P90. (D, E) H&E staining of the subventricular zone in the forebrain of 8-months-old R26SmoM2 and Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice. (F, G) Ki67 immunostaining showing no difference of proliferation in the subventricular zones of R26SmoM2 and Gli1CreER;R26SmoM2 mice.

Supplemental figure 2. SmoM2 activation regulates survival and differentiation of cultured juvenile myogenic progenitors in vitro. (A) Caspase 3/7 activity in isolated myogenic progenitor cells from CAGGSCreER;R26SmoM2 mice with 4OH-TM treatment in the presence of apoptotic stimulus CHX. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of MyHC in isolated myogenic progenitor cells in growth medium and differentiation medium with or without 4OH-TM.