Abstract

Beta-amyloid (Aβ) in brain is a major factor involved in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) that results in severe memory deficit. Our recent studies demonstrate pharmacogenetic differences in the effects of inhibitors of cathepsin B to improve memory and reduce Aβ in different mouse models of AD. The inhibitors improve memory and reduce brain Aβ in mice expressing the wild-type (WT) β-secretase site of human APP, expressed in most AD patients. However, these inhibitors have no effect in mice expressing the rare Swedish (Swe) mutant APP. Knockout of the cathepsin B decreased brain Aβ in mice expressing WT APP, validating cathepsin B as the target. The specificity of cathepsin B to cleave the WT β-secretase site, but not the Swe mutant site, of APP for Aβ production explains the distinct inhibitor responses in the different AD mouse models. In contrast to cathepsin B, the BACE1 β-secretase prefers to cleave the Swe mutant site. Discussion of BACE1 data in the field indicate that they do not preclude cathepsin B as also being a β-secretase. Cathepsin B and BACE1 may participate jointly as β-secretases. Significantly, the majority of AD patients express WT APP and, therefore, inhibitors of cathepsin B represent candidate drugs for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid, cathepsin B, cleavage site, inhibitor, memory, pharmacogenetics, protease, transgenic AD mice

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) results in severe memory loss resulting from age-related neurodegeneration in the brain, caused in large part by accumulation of neurotoxic β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides. The majority of AD patients are afflicted with sporadic AD that is not linked to genetic mutations (Blennow et al., 2006; Turner, 2006). A smaller portion of AD patients possess familial forms of AD with inherited genetic mutations, especially mutations of APP and presenilins that result in increased Aβ production and memory deficit when overexpressed in transgenic mouse models of AD (Price and Sisodia, 1998; Masliah and Rockenstein, 2000; Dodart et al., 2002). Development of effective therapeutic agents to improve memory in AD is essential for the increasing numbers of AD patients who are becoming afflicted as the aged population grows.

A promising therapeutic approach for AD is to develop drugs which reduce the production of brain beta-amyloid peptides (Aβ) because their abnormal accumulation is thought to be a major factor in causing the disease. Aβ peptides are produced from amyloid precursor protein (APP) by proteolytic cleavage at the β-secretase and γ-secretase sites. The majority of AD patients express wild-type (WT) APP, but a few families express APP containing mutations at those sites, which results in Aβ accumulation and onset of the disease. Because the mutant APP forms produce more Aβ, mutant APP forms have often been used in developing animal models to identify potential AD therapeutics. However, since most AD patients express WT APP, it is essential to investigate drug candidates in models expressing WT APP because Aβ production from the different mutant APP form may differ and affect drug development strategies.

In fact, the dramatically different effects of inhibition of the cysteine protease cathepsin B on memory deficit and brain Aβ in animal models expressing WT APP vs. those expressing APP containing the Swedish (Swe) mutant β-secretase site of APP (Hook et al., 2008a) demonstrate the importance of evaluating the different AD animal models. Notably, genetic deletion of cathepsin B in transgenic mice expressing human WT APP results in significant reduction of brain Aβ but has no effect in mice expressing Swe APP (Hook et al. 2009). These data suggest the importance of investigating potential differences in processing of WT APP compared to mutant APP (Chow et al, 2010).

This review explains the basis of the novel pharmacogenetic features of inhibitors to cathepsin B as being due to the unique cleavage specificity of cathepsin B for the WT β-secretase site of APP, but not the Swedish mutant β-secretase site. These new findings about cathepsin B suggest that it may participate as a beta-secretase. Together with findings in the field showing that BACE1 participates in Aβ production as a β-secretase activity (Hussain et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 1999; Vassar et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Cai et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2001; Roberds et al., 2001), cathepsin B may function with BACE1 in Aβ production. Significantly, the pharmacogenetic properties of the class of molecules that inhibit cathepsin B predicts that such inhibitors may be therapeutically efficacious for the majority of AD patients. The emerging role of cathepsin B as a drug target for AD may benefit future development of therapeutic agents for AD.

Pharmacogenetic differences in drug response in AD mice expressing APP with the wild-type β-secretase site, compared to those expressing the rare Swedish mutant site of APP

Inhibitors of cathepsin B result in memory improvement and reduction in brain Aβ in mice expressing human APP with the wild-type β-secretase site of APP

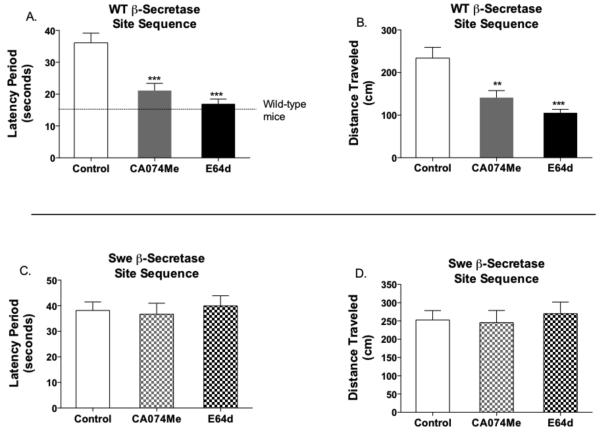

Significant results show that inhibitors of cathepsin B improve memory and reduce Aβ in transgenic mice expressing human APP with the WT β-secretase site, expressed in the London APP mouse model of AD (Hook et al., 2008a). Administration of the CA074Me and E64d inhibitors both resulted in substantial improvement in memory deficit in the London AD mouse model, assessed by the Morris water maze memory test that measures latency time to swim to a hidden platform (Figure 1A). Notably, the reduced latency time after inhibitor treatment indicates substantial improvement in memory, which approached that of normal mice. The effectiveness of the inhibitors to improve memory is also indicated by the reduction in distance traveled to the hidden platform (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Inhibitors of cathepsin B improve memory and reduce Aβ in AD mice expressing human APP with the wild-type β-secretase site, but not in mice expressing human APP with the Swedish mutant site.

Results from the original study of Hook et al., 2008a are summarized in this figure.

Panels A, B. Inhibitors of cathepsin B improve memory deficit in mice expressing human APP with the wild-type (WT) β-secretase site. APP mice (12 months age) that express human APP with the WT β-secretase site and the London mutation (V717I near the γ-secretase site (known as London APP mice), representing a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), were treated with inhibitors of cathepsin B. The inhibitors CA074Me and E64d were administered into brains by osmotic minipump (ALZET minipump) at a rate of 0.25 μl/hr of 1 mg/ml inhibitor in saline with 1.5% DMSO, corresponding to an estimated dose rate of 0.006 mg/day or 0.013 mg/day–gm brain weight. After 28 days of continuous infusion of inhibitor or control saline, memory function was assessed by the Morris water maze test. Inhibitors resulted in improved memory as shown by the shorter latency time (panel A) for mice to swim to a hidden platform after pretraining, and the shorter distance traveled to reach the platform (panel B) (Hook et al., 2008a). The dotted line indicates the latency time of normal mice that do not express human APP. Statistical significance for improved memory is indicated by ***p < 0.0001 (student’s t-test), and for reduced distance traveled **p<0.0001.

C, D. Inhibitors of cathepsin B have no effect in mice expressing human APP with the rare Swedish (Swe) mutant β-secretase APP site. London mice expressing human APP with the Swe mutant β-secretase site of APP (known as Swe/London APP mice) were treated with inhibitors of cathepsin B as described for panels A and B, and memory was assessed by the Morris water maze test. Results showed that these inhibitors resulted in no change in latency time (panel C) and no change in distance traveled by the mice to the platform (panel D) evaluated by the Morris water maze memory test.

The inhibitor treatment reduced amyloid plaque load in brain, indicating that the compounds reduced a neuropathological hallmark of AD (Hook et al., 2008a). Furthermore, the CA074Me and E64 inhibitors substantially reduced both Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in brain (Figure 2A,B). The CA074Me and E64 inhibitors also reduced brain levels of CTFβ (Figure 3A) derived from APP by β-secretase processing. Importantly, mice remained healthy after inhibitor treatment. These novel results demonstrate the in vivo effectiveness of these inhibitors of cathepsin B to improve memory deficit with reduction in brain Aβ peptides and amyloid plaque load in the London APP mouse model of AD expressing human APP with the WT β-secretase site.

Figure 2. Reduction of Aβ peptides by inhibitors of cathepsin B in AD mice expressing human APP with wild-type β-secretase site, but not in mice expressing APP with the Swedish mutant site.

Panels A, B. Reduction of brain Aβ40 and Aβ42 by inhibitors to cathepsin B administered to AD mice expressing the wild-type site of APP. After in vivo administration of CA074Me or E64d for 28 days by continuous osmotic minipump infusion into brains of mice expressing APP with the wild-type β-secretase site (in London APP mice, as described in legend of figure 1), Aβ40 (panel A) and Aβ42 (panel B) brain levels were measured by ELISAs. Inhibitors resulted in significant reduction of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides with ***p < 0.001 (by student’s t-test). Panels C, D. Aβ peptides are not reduced in brains of mice expressing APP with the rare Swedish mutant β-secretase site after treatment with cathepsin B inhibitors. After administration of CA074Me or E64d to mice expressing APP with the Swe mutant site of APP (Swe/London APP mice), Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in brains were measured. Results show no change in brain Aβ40 (panel C) or Aβ42 (panel D) peptides in Swe/London APP mice after inhibitor treatment.

These results were originally reported by Hook et al., 2008a.

Figure 3. Reduction of CTFβ derived from APP after administration of inhibitors of cathepsin B to AD mice expressing the wild-type β-secretase site of APP, but not in mice expressing Swedish mutant APP.

A. CTFβ levels in brain are reduced by inhibitors of cathepsin B administered to AD mice expressing human APP with the wild-type β-secretase site. CTFβ (C-terminal β-secretase fragment) results from cleavage of APP at its β-secretase site. Quantitative densitometry of western blots detecting the CTFβ band (~12 kDa) (performed as described in Hook et al., 2008) indicates its reduction after treatment of London APP mice (AD mice expressing human APP with the WT β-secretase site) with the inhibitors CA074Me or E64d (Panel A). Statistical significance of ***p < 0.0001 is indicated (by student’s t-test).

B. Treatment of Swedish/London APP mice with inhibitors of cathepsin B has no effect on CTFβ. After administration of CA074Me or E64d inhibitors to Swe/London APP mice, analyses of CTFβ (by quantitative western blots of the CTFβ band) indicated no change in CTFβ levels in brain after inhibitor treatment of Swe/London APP mice (Panel B).

These results were originally reported by Hook et al., 2008a.

No effect in Swedish mutant APP mice treated with inhibitors of cathepsin B

In contrast, distinct pharmacogenetic differences in inhibitor response was observed in the Swedish mutant APP mouse model of AD (Hook et al., 2008a), compared to the substantive effects on memory improvement in the London AD mice expressing APP with the wild-type β-secretase site. Transgenic mice expressing human Swedish mutant APP have been utilized as a mouse model of AD (Hsiao et al., 1996; Price and Sisodia, 1998; Masliah and Rockenstein, 2000; Selkoe and Schenk, 2002). The Swedish APP possesses the mutant Asn-Leu residues at the β-secretase cleavage that differs from the WT sequence of Lys-Met at that site (Citron et al., 1992).

Most interestingly, administration of the inhibitors of cathepsin B, CA074Me and E64d to Swedish mutant mice (Swedish mutation in the London APP mice, ie., Swe/London APP mice) resulted in no effect on memory deficit in the Swedish mutant APP mice, as measured by the Morris water maze test of latency time and distance traveled to reach the hidden platform (Figure 1C,D) (Hook et al., 2008a). Furthermore, inhibitors resulted in no change in brain levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 (Figure 2B,C), or CTFβ (Figure 3B) in mice with the Swedish mutation of APP (Swe/London APP mice).

The effectiveness of inhibitors in AD mice expressing the wild-type β-secretase site of APP is relevant to the majority of AD patients

These novel results demonstrate the unique pharmacogenetic features of the CA074Me and E64d inhibitors to improve memory deficit and reduce brain Aβ in genetic models of AD expressing human APP with the WT β-secretase site. Moreover, these cathepsin B inhibitors reduce brain Aβ in normal guinea pigs (Hook et al., 2007a,b), indicating that these inhibitors are efficacious in these animals expressing WT APP with production of endogenous levels of Aβ. Significantly, since the majority of the AD population expresses WT APP, the effectiveness of these inhibitors to reduce Aβ generated from APP with the WT β-secretase site are relevant to the human AD disease condition.

Validation of the cathepsin B target by in vivo gene knockout studies

The CA074Me inhibitor enters cells and is then converted by esterases to CA074, a selective inhibitor of cathepsin B (Towatori et al., 1991; Yamamoto et al., 1992). Therefore, the effectiveness of CA074Me to improve memory deficit and reduce Aβ in the London APP mouse model of AD implicates a role for cathepsin B as the candidate inhibitor drug target. To confirm the predicted role of cathepsin B for Aβ production and memory function, the effects of cathepsin B gene knockout on Aβ production was investigated (Hook et al., 2009).

Knockout of the cathepsin B gene in mice expressing human wild-type APP (WT APP) results in substantial decrease of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in brain (Figure 4A,B). The cathepsin B knockout mice also showed a significant decrease in brain levels of the C-terminal β-secretase fragment (CTFβ) derived from APP (Figure 5A), suggesting inhibition of β-secretase activity. In contrast, knockout of cathepsin B in mice expressing human APP with the rare Swedish (Swe) and Indiana (Ind) mutations had no effect on Aβ levels in brain (Figure 4C,D), and had no effect on CTFβ (Figure 5B). The different effects of cathepsin gene knockout to reduce Aβ in mice expressing human WT APP, but not in the genetic variant of mice expressing APP with the Swedish mutation, shows that the genetic animal model affects the outcomes of cathepsin B function in Aβ production.

Figure 4. Knockout of the cathepsin B gene results in reduced Aβ in mice expressing human wild-type APP, but not in mice expressing the Swedish mutant APP.

Panels A, B. Reduction of Aβ40 and Aβ42 occurs in cathepsin B knockout mice that express human wild-type (WT) APP. The effects of cathepsin B knockout (CatB−/−) on brain levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were assessed in mice expressing human WT APP. Results show substantial reduction of Aβ40 (panel A) and Aβ42 peptides (panel B) in cathepsin B knockout mice (CatB−/−), compared to mice with normal cathepsin B gene (CatB+/+). Significant reductions in Aβ peptide levels are indicated by **p < 0.007 (student’s t-test).

Panels C, D. No change Aβ40 or Aβ42 in mice expressing human APP with the Swedish (Swe) mutant site during cathepsin B knockout. Mice that express human APP with the Swe mutation (and the Indiana mutation near the γ-secretase site, known as Swe/Ind APP mice) were generated with knockout of the cathepsin B gene. Brain levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were measured, and results showed that Aβ40 (panel C) and Aβ42 (panel D) in Swe/Ind APP mice were not changed in the cathepsin B knockout condition (CatB−/−) compared to normal cathepsin B gene expression (CatB+/+).

These results were originally reported by Hook et al., 2009.

Figure 5. CTFβ is reduced by cathepsin B knockout in mice expressing human wild-type APP, but not in mice expressing APP with the Swedish mutant β-secretase site.

A. Reduction of CTFβ in cathepsin B knockout mice expressing human wild-type (WT) APP. Brain levels of CTFβ were measured in mice with knockout of the cathepsin B gene (CatB−/−) that express human WT APP, and in the same mice with normal cathepsin B (CatB+/+). Quantitation of CTFβ western blots illustrate substantial reduction of CTFβ in cathepsin B knockout compared to normal cathepsin B expression in mice expressing human WT APP. Statistical significance is indicated by ***p<0.0002 (student’s t-test).

B. CTFβ in cathepsin B knockout mice mice expressing human APP with the Swedish (Swe) mutant β-secretase site is not altered. CTFβ levels in brains of cathepsin B knockout mice, compared to mice with normal cathepsin B gene expression, were not changed in mice that express mutant human APP with the Swe mutant β-secretase site and the Indiana mutation near the γ-secretase site (Swe/Ind APP mice). Quantitation of relative CTFβ levels in brain was assessed by densitometry of western blots that detected CTFβ (~12 kDa) (Hook et al., 2009).

These results were originally reported by Hook et al., 2009.

Other studies have confirmed the lack of effect of cathepsin B knockout on Aβ in mice expressing APP with the Swe mutation (Mueller-Steiner et al., 2006). However, the Mueller-Steiner studies did not examine effects of cathepsin B knockout in mice expressing WT APP. We show the contrasting difference in effectiveness of cathepsin B gene knockout to reduce Aβ in mice expressing WT APP, but not Swe mutant APP mice (Hook et al., 2009).

Furthermore, gene silencing of cathepsin B by siRNA in normal WT hippocampal brain neurons (in primary culture) reduces the amount of Aβ in the regulated secretory pathway (Klein et al., 2009). These studies also showed that the CA074Me inhibitor reduces Aβ in the regulated secretory pathway of rat hippocampal neurons, indicating a role for cathepsin B in Aβ production.

These data from multiple groups validate cathepsin B as a target for development of drug inhibitors to lower Aβ in the majority of AD patients expressing WT APP.

Distinct cleavage specificity of cathepsin B for the wild-type (WT) β-secretase site of APP, but not the Swe mutant β-secretase site, provides the basis for pharmacogenetic features

The in vivo effects of the inhibitors of cathepsin B to reduce brain levels of CTFβ (C-terminal β-secretase fragment) derived from APP suggest a β-secretase role for cathepsin B. Therefore, cathepsin B cleavage of the WT β-secretase site was evaluated with the model Z–Val–Lys–Met–↑MCA substrate that mimics the WT β-secretase cleavage site (indicated by arrow) (see Figure 6A) (Hook et al., 2005) Further, the question of whether cathepsin B cleaves the Swedish mutant β-secretase site was assessed with the substrate Z-Val-Asn-Leu-←MCA (mutant residues are underlined) that mimics the Swedish mutant site (Figure 6A). Significantly, cathepsin B showed clear preference for cleaving the WT β-secretase substrate, and essentially no activity for the Swe mutant β-secretase substrate (Figure 6B). The distinct preference of cathepsin B for the WT β-secretase site is indicated by its high catalytic efficiency represented by its kcat/Km value of 3.17 × 105 M–1sec1 (Hook et al., 2008a,b), indicating an active enzyme.

Figure 6. Cleavage specificity of cathepsin B for the wild-type β-secretase site of APP.

A. Z-Val-Lys-Met-MCA substrate mimics the wild-type (WT) β-secretase site of APP.

Normal WT APP possess the peptide sequence -Val-Lys-Met-↓ adjacent to its β-secretase cleavage site. The Swedish (Swe) mutation is indicated by the mutant Asn-Leu residues that substitute for the normal Lys-Met residues adjacent to the β-secretase cleavage site. These WT and Swe mutant peptide sequences were utilized for design of protease cleavage site specific assays for the WT β-secretease site and the respective Swe mutant site, as shown in part ‘b’ of this figure.

B. Cathepsin B displays specificity for cleaving the WT β-secretase site, but not the Swedish mutant β-secretase site. A cleavage site specific protease assay was designed to detect cleavage at the WT β-secretase site utilizing the Z-Val-Lys-Met-←MCA (Z-V-K-M-MCA) substrate that mimics the WT cleavage site. In parallel, the substrate Z-Val-Asn-Leu-←MCA was utilized to assay protease cleavage at the Swedish (Swe) mutant site (Swe mutant residues are underlined). These substrates provided cleavage site specific protease assays for cleavage of the WT or Swe mutant sites. Assay of cathepsin B with these substrates provided comparison of its high specific activity (pmol AMC/min/μg enzyme) for the WT substrate, and essentially no activity with the Swe mutant substrate. These results were originally reported by Hook et al., 2008a.

Analyses with longer peptide substrates also show that cathepsin B cleaves the wild-type β–secretase site (Hook et al., 2002; Bohme et al., 2008). The endogenous cathepsin B purified from Aβ-containing secretory vesicles was found to cleave the wild-type β-secretase site of the peptide substrate SVK←MDAEF (arrow shows β-secretase site) (Hook et al., 2002). Furthermore, cathepsin B cleaves the internally quenched fluorescent peptide substrates that contain the wild-type β-secretase site within the RE(Edans)EVKM←DAEFK(Dabcl)R-NH2 substrate (Bohme et al., 2008). These are typical long peptide substrates utilized to evaluate cleavage of the β-secretase site by β-secretases (Yan et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 1999; Hook et al., 2002).

The selectivity of cathepsin B cleavage for the WT β-secretase site is consistent with the finding that inhibitors of cathepsin B administered to mice expressing APP with the WT β-secretase site result in reduction of CTFβ and Aβ (Hook et al., 2008a). However, since cathepsin B does not cleave the Swedish mutant β-secretase site of APP, inhibitors of cathepsin B do not inhibit production of Aβ generated the Swedish mutant APP (Hook et al., 2008a).

The cathepsin B knockout studies validate this cysteine protease as a candidate drug target for inhibitors to reduce Aβ in brain, indicating that inhibitors of cathepsin B can reduce Aβ. Indeed, the CA074 and E64c inhibitors of cathepsin B in their cell permeable forms (CA074Me and E64d which are converted by intracellular esterases to CA074 and E64c) effectively reduce Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in vivo (Hook et al., 2008a). Notably, these inhibitors significantly improved memory function (Hook et al., 2008a), as described earlier in this review.

Furthermore, the CA074 and E64c inhibitors do not affect BACE1 activity that functions as β-secretase (Table 1). The compounds CA074 and E64c, at 0.1 or 1.0 μM, do no affect recombinant BACE 1 activity (Table 1) Thus, the lack of the effects of these inhibitors on BACE 1 in vitro indicate that the inhibitors in vivo have no effect on BACE 1. Thus, direct inhibition of cathepsin B activity by the selective inhibitor CA074 (CA074 generated intracellularly from CA074Me that was administered to the animal) results in reduced brain Abeta (Hook et al., 2008a).

Table 1.

Inhibitors of Cathepsin B Have No Effect on BACE 1 Activity

| Inhibitor | BACE 1 Activity, Percent of Control |

|---|---|

| None | 100% ± 2% |

| CA074, 0.1 μM | 101% ± 10% |

| CA074, 1.0 μM | 94% ± 2% |

| E64c, 0.1 μM | 98% ± 4% |

| E64c, 1.0 μM | 96% ± 3% |

| Statine BACE 1 Inhibitor, 1 μM | 8% ± 0.1 %* |

The activity of purified recombinant BACE 1 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was evaluated in the presence of inhibitors of cathepsin B consisting of CA074 that selectively inhibits cathepsin B and E64c that inhibits cysteine proteases; each inhibitor was tested at 0.1 μM and 1.0 μM. The inhibitors of cathepsin B showed no effects on BACE 1 activity, assayed with the substrate Mca-S-E-V-N-L-D-A-E-F-R-K(Dnp)-R-R-NH2. However, BACE 1 activity was nearly completely inhibited by the statine BACE 1 inhibitor (Sinha et al, 1999). Effects of inhibitors on BACE 1 activity are expressed as percent of control (no inhibitor), indicated by the mean of replicate assays.

Statistically significant compared to control (100% activity) (p < 0.005, student’s t-test).

Clearly, the selectivity of cathepsin B for the WT (rather than the Swe mutant) β-secretase site of APP provides the basis for the pharmacogenetic differences in the effectiveness of inhibitors to cathepsin B to reduce Aβ and improve memory in transgenic mice expressing human APP with WT, but not in mice expressing the Swe mutant site of APP. Because the majority of AD patients express the WT β-secretase site of APP, cathepsin B is relevant for production of Aβ in most AD patients.

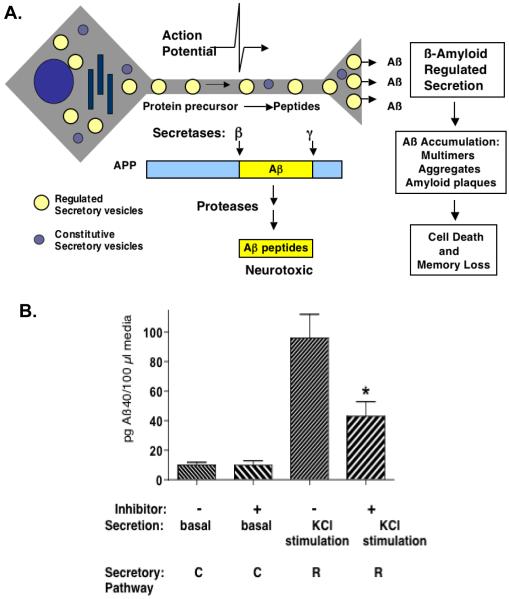

Neurobiology of cathepsin B for Aβ production in the regulated secretory pathway of neurons

Aβ peptides are secreted from neurons which leads to accumulation of extracellular Aβ in amyloid plaques in AD brains (Price and Sisodia, 1998; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Selkoe and Schenk, 2003). The Aβ secretory process is an integral component of the disease process (illustrated in Figure 7A). Neurons possess two distinct secretory pathways consisting of (1) regulated, activity-dependent stimulation of secretion that releases neurotransmitters and chemical molecules for cell-cell communication, and (2) basal secretion from the constitutive secretory pathway (Figure 7A) (Gumbiner and Kelly, 1982; Lodish et al., 1999). Investigation of Aβ secretion has revealed its secretion from the major regulated secretory pathway, and a portion of Aβ is secreted from the basal constitutive secretory pathway (Nitsch et al., 1992, 1993; Jolly-Tornetta et al, 1993; Hook et al., 2002, 2005).

Figure 7. Reduction of Aβ in the major regulated secretory pathway by CA074Me inhibitor of cathepsin B.

A. Regulated and constitutive secretory pathways for secretion of Aβ from neurons. APP processing occurs during axonal transport from the neuronal cell body to nerve terminals where Aβ is secreted to the extracellular domain. Within neurons, APP processing occurs via proteolysis by β-secretase and γ-secretase proteases to generate Aβ40 and Aβ42. Secretion of Aβ occurs by the major regulated secretory pathway that provides activity-stimulated secretion of Aβ (Nitsch et al., 1992, 1993; Jolly-Tornetta, 1998; Hook et al., 2002, 2005). Secretion of Aβ also occurs via basal, constitutive secretion that provides a lesser portion of extracellular Aβ. Secreted extracellular Aβ peptides accumulate as oligomers and aggregates in amyloid plaques, and cause loss of memory in Alzheimer’s disease.

B. Reduction of Aβ production in the regulated secretory pathway by CA074Me inhibitor of cathepsin B. Neuronal-like chromaffin cells were treated with the inhibitor CA074Me (50 μM) for 18 hours. Regulated secretion (R) was induced by KCl (50 μM) for 15 minutes, and Aβ40 was measured in secretion media. Secretion by the regulated secretory pathway (R) is represented by KCl-stimulated secretion. Basal secretion (no KCl) represents secretion from the constitutive secretory pathway (C). Results show significant reduction by CA074Me of Aβ secreted from the regulated secretory pathway, with *p < 0.05 (student’s t-test). These results were originally reported by Hook et al., 2005.

Direct comparison of the relative amounts of Aβ secreted from these two secretory pathways in neuronal-like chromaffin cells (Hook et al., 2002, 2005) revealed that a major portion of Aβ is secreted from the regulated secretory pathway. Stimulation of the regulated secretory pathway by nicotine or KCl depolarization resulted in prominent increase in Aβ secretion (Figure 7B). However, basal unstimulated secretion of Aβ represented a smaller portion of secreted Aβ. Furthermore, studies in rat hippocampal neurons also demonstrate regulated secretion of Aβ peptides (Klein et al., 1999). These findings indicate that a major portion of secreted Aβ is present in the regulated secretory pathway that provides extracellular Aβ that accumulates in AD brains.

Based on knowledge that the regulated secretory pathway provides a major portion of secreted extracellular Aβ, regulated secretory vesicles that contain Aβ and APP (Efthimiopoulos et al., 1996; Tezapsidis et al., 1998) should also have β-secretase activity for Aβ production. Therefore, protease activity assayed with the Z-Val-Lys-Met-←MCA substrate, mimicing the WT β-secretase site (indicated by arrow), was purified from regulated secretory vesicles isolated from neuronal-like chromaffin cells (Hook et al., 2002). Identification of the purified protease by mass spectrometry indicated cathepsin B as the candidate β-secretase (Hook et al., 2005). Notably, inhibitors of cathepsin B reduced production of Aβ in the isolated regulated secretory vesicles (Hook et al., 2005). These inhibitors of cathepsin B also reduced production of Aβ in the regulated secretory pathway of hippocampal neurons (rat) (Klein et al., 2009). But these inhibitors had no effect on Aβ in the constitutive secretory pathway. These findings indicate the key role of cathepsin B in Aβ production in the regulated secretory pathway of neurons.

Participation of cathepsin B in production of Aβ via cleavage of the wild-type β-secretase site of APP in the regulated secretory pathway of neurons

Aβ production in regulated secretory vesicles by cathepsin B has been demonstrated in several neuronal and animal model systems consisting of neuronal systems in culture and in animal models from bovine, guinea pig, mouse, and rat (summarized in Table 2) (Hook et al., 2005, 2007a/b, 2008a,b, 2009; Bohme et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2009). These studies support the hypothesis that cathepsin B may produce Aβ from APP via β-secretase activity in the regulated secretory pathway, but not the constitutive secretory pathway. Furthermore, cathepsin B in regulated secretory vesicles cleaves the wild-type β-secretase site of APP to produce Aβ. Inhibitors of cathepsin B are hypothesized to reduce Aβ by lowering its production in the regulated secretory pathway through inhibition of β-secretase activity.

Table 2.

Multiple Neuronal Models Illustrate Production of Aβ by Cathepsin B

| Neuronal Models: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated Regulated Secretory Vesicles (bovine) (1) |

Neuronal- like Chromaffin Cells in Primary Culture (bovine) (1) |

Brain Neurons in Primary Culture (rat) (2) |

Normal Guinea Pig Brain (3.4) |

Transgenic Mice Expressing WT hAPP, Brain (5) |

Transgenic Mice Expressing hAPPLon, Brain (6) |

|

|

Cat. B

reduced by: |

Chemical Inhibitors |

Chemical Inhibitor |

siRNA Silencing or chemical inhibitor |

Chemical Inhibitors |

Gene Knockout |

Chemical inhibitors |

|

Effect on

Aβ: |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

References (1) to (6) correspond to Hook et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2009; Hook et al., 2007a,b; Hook et al., 2009; and Hook et al., 2008a, respectively.

BACE1 β-secretase data does not preclude cathepsin B as also being a β-secretase

There has been much investigation in the field on the aspartyl protease BACE1 that functions as β-secretase (Sinha et al., 1999; Vassar et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1999; Cai et al., 2001; Hussain et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Luo et al., 2001; Roberds et al., 2001). With recent data indicating that cathepsin B is involved in Aβ production (Hook et al., 2005, 2007a/b, 2008a,b, 2009; Bohme et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2009), the combined findings in the field indicate that cathepsin B and BACE1 function jointly in Aβ production. Analyses of the BACE1 studies indicate that they are consistent with the hypothesis for joint roles of these proteases for Aβ production, explained in this section.

BACE1 prefers to cleave the Swedish mutant β-secretase site, rather than the WT β-secretase site of APP

The Swedish (Swe) mutant APP possesses alterations of two amino acids at the β-secretase site that leads to increased Aβ; this rare mutation is present in an extended family (Citron et al., 1992). The Swe mutation provided rationale in the field to search for β-secretase using a substrate with the Swe mutation, leading to identification of BACE1 (Hussain et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 1999; Vassar et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000). These studies showed that although BACE1 readily cleaves the Swe β-secretase site, it has poor efficiency for cleaving the WT β-secretase site.

BACE1 activity for the wild-type β-secretase substrate is extremely low, cleaving it with only low kcat/Km values of 40-60 M−1s−1 (Lin et al., 2000; Shi et al., 2001), whereas proteases acting on relevant substrates have kcat/Km values that range between ten of thousands to a few millions (Dunn and Hung, 2000). In order for BACE1 to obtain a kcat/Km that approaches that of other proteases for their substrates, 7 out of 8 amino acid residues in the wild-type β-secretase peptide substrate must be modified (Turner et al., 2001). On the other hand, cathepsin B has a kcat/Km for cleaving wild-type β-secretase site substrates of 317,000 M−1s−1 (Hook et al., 2008a, b). These kinetic properties demonstrate the low effectiveness of BACE1 for cleaving the wild-type β-secretase site, compared to the highly effective cathepsin B cleavage of wild-type β-secretase site substrates.

The difference in effectiveness of BACE1 to cleave the Swe mutant compared to the wild-type β-secretase sites is consistent with knowledge of the importance of amino acid residues adjacent to protease cleavage sites. The Swe mutation substitutes the neutral asparagine residue for the positively charged lysine residue at the key P2 protease-substrate recognition site. The different uncharged compared to charged residue at the P2 position is likely to be critical for recognition and cleavage site by proteases (Barrett et al., 1998; Siegel et al., 1999; Hook et al., 2008b). Such protease cleavage properties can explain the preference of BACE1 for the Swe mutant β-secretase site compared to the WT site.

BACE1 knockout in Swe APP expressing mice

Since BACE1 cleaves the Swe mutant APP, investigators have utilized transgenic mice expressing human Swe mutant APP as an AD model for studies of BACE1 gene knockout. Indeed, a study by Luo and colleagues (Luo et al, 2001) showed that knockout of BACE1 reduced brain Aβ and CTFβ, which provides support for involvement of BACE1 as β-secretase for the Swe mutant APP. These BACE1 studies, though, do not rule out a role for cathepsin B in production of Aβ from WT APP.

Beta-secretase activity in BACE1 knockout mice

Seemingly convincing evidence for BACE1 as the brain β-secretase by a study by Roberds et al 2001 (Roberds et al., 2001) found that BACE1 knockout mice completely lack brain β-secretase activity. But a closer reading of the study indicates that the β-secretase assays contained E64, a potent inhibitor of cathepsin B. Thus, the assay condition with the E64 inhibitor made it impossible to detect the cysteine protease activity of cathepsin B. Therefore, the assay conditions by Roberds does not rule out cathepsin B as having β-secretase activity.

Aβ production and secretion in neurons of BACE1 knockout mice

The Roberds study found lower Aβ levels in media from cultured brain neurons obtained from BACE1 knockout mice which implicated participation of BACE1 (Roberds et al., 2001). But the Aβ in “conditioned medium” indicates constitutive secretion of Aβ because the neurons were not stimulated to secrete. The Roberds study did not measure regulated secretion of Aβ and, therefore, their data do not rule out participation of cathepsin B. The same analysis applies to a study by Cai and colleagues (Cai et al. 2001), which also found reduced Aβ in conditioned medium secreted from neurons from BACE1 knockout mice, indicating a role for BACE1 in the constitutive secretory pathway. Again, the study did not address regulated secretion and, therefore, does not rule out cathepsin B participation in Aβ production in the regulated secretory pathway.

BACE1 and Aβ production from normal compared to super high levels of APP: relationship to AD patients expressing physiological normal levels of APP

Alzheimer’s disease patient brains possess physiologically normal levels of APP (Hirata-Fukae et al., 2008). Therefore, several studies have investigated the effects of BACE1 on Aβ production from endogenous, normal levels of wild-type mouse brain APP, which express APP containing the human wild-type β-secretase site sequence. A study by Matsuoka and colleagues showed that completely knocking out the BACE1 gene (BACE1−/−) in wild-type mice essentially eliminated all of the mouse brain Aβ1-40 and reduced Aβx-40 by about 25% (Nishitomi et al., 2006). However, that paper also shows that partial BACE1 gene deletion (BACE1 −/+) has no effect on mouse brain Aβ. A more recent study by the same group showed that overexpression of BACE1 in wild-type mice has no effect on mouse brain Aβ levels, which led that group to conclude that BACE1 “has minimal effect on the level of endogenous Abeta” and that “other factors must be involved in modulation of Aβ production in adult and aging brain” (Hirata-Fukae et al., 2008). Taken together, these data suggest that levels of BACE 1 protein appear to not be rate-limiting in the production of Aβ peptides. These results raise questions as to the role of BACE1 in producing Aβ from the physiologically normal levels of wild-type APP in AD patients. Thus, these data open the possibility that another protease, such as cathepsin B, may also be involved in Aβ production.

Another study showed that at super high levels of APP expression in transgenic mice, BACE1 gene knockout resulted in decreased brain Aβ levels (McConlogue et al., 2007). The McConlogue study used PDAPP transgenic mice that express extremely high levels of APP. These findings indicate that BACE1 can function with very high, non-physiological levels of APP. It is known that protease enzyme activities are dependent on substrate levels (Voet and Voet, 2004; Hook et al., 2008b; Voet and Voet, 2004). Thus, the data in the field suggest involvement of BACE1 in processing high levels of APP substrate, but data suggest that BACE1 has lesser effects on normal physiological levels of APP for Aβ production.

The important question is what protease target can be inhibited under conditions of normal APP levels to reduce Aβ? This question is addressed by results showing that inhibition of cathepsin B by CA074Me reduces brain Aβ in brains of normal wild-type guinea pigs (Hook et al., 2007a). These data indicate that cathepsin B functions at normal levels of APP for Aβ production. Furthermore, knockout of the cathepsin B gene in mice expressing human APP with the wild-type β-secretase site results in reduced brain Aβ and substantial improvement in memory deficit (Hook et al., 2008a).

Despite the fact that BACE1 was discovered as a β-secretase more than a decade ago, combined with the expenditure of extraordinary resources and effort to develop BACE1 inhibitors, no BACE1 inhibitor is known to be clinically effective to reduce brain Aβ in patients. There is clearly a critical need for effective AD therapeutic agents. The inhibitors of cathepsin B are effective Aβ lowering agents that result in improved memory in AD mouse models. It is, thus, essential to develop such inhibitors of cathepsin B as candidate therapeutic agents for AD patients.

An alternative, but unlikely, hypothesis is that cathepsin B activates α-secretase

An alternative effect of inhibitors of cathepsin B is that they may stimulate the α-secretase pathway and thereby reduce Aβ. Alpha-secretase cleaves within the Aβ domain of APP and thus, precludes formation of Aβ. While this may be possible, it is not a likely mechanism. The hypothesis that cathepsin B possesses β-secretase activity is the more probable means by which the cathepsin B inhibitors reduce Aβ, as explained here.

The inhibitors of cathepsin B increased brain levels of sAPPα derived from APP by from α-secretase cleavage (Hook et al., 2008a). This observation can be explained by the inhibitor-induced decrease in β-secretase activity, documented by decreased levels of CTFβ derived from APP by β-secretase, which could result in a larger portion of APP available for α-secretase cleavage. Alternatively, the inhibitors could increase α-secretase activity, but this alternative is highly unlikely because of the fact that cathepsin B was initially identified based on its β-secretase activity for purification, and not α-secretase activity (Hook et al., 2005). Thus, it would be pure serendipity that the protease found through its β-secretase activity also activates an entirely different protease. While not impossible, this would not be expected and thus improbable. Rather, the more straight-forward explanation is that cathepsin B is performing the β-secretase activity that was the basis for its purification (Hook et al., 2005).

Studies of BACE1 also show that sAPPα is increased due to deleting or inhibiting this β-secretase (Nishitomi et al., 2006). The study concluded that the sAPPα increase is likely due to a reduction in β-secretase activity causing more APP substrate to be available for α-secretase production of sAPPα. Similarly, we also explain that the increase in sAPPα resulting from cathepsin B inhibition or deletion may be due to reducing β-secretase activity causing increased APP for α-secretase cleavage (Hook et al., 2008a). Overall, the cathepsin B data support the hypothesis for cathepsin B participating as a β-secretase for Aβ production.

Conclusion: Majority of AD patients express wild-type APP and are predicted to respond to inhibitors of cathepsin B as candidate therapeutic agents

Cathepsin B is a valid target for therapeutic reduction of brain Aβ, as indicated by the data that inhibitors of cathepsin B result in effective improvement in memory deficit and reduction of brain Aβ in mice expressing human APP with the WT β-secretase site. The pharmacogenetic differences in drug response in AD mouse models with the WT or Swe mutant β-secretase site indicate the importance of genetic features for drug efficacy. Notably, because the majority of AD patients express WT APP, and cathepsin B has specificity for the WT β-secretase site, cathepsin B is a valid drug target for AD. These findings suggest that development of cathepsin B inhibitors may be useful for novel therapeutic strategies in AD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIA/NIH R21 Grant AG027446 and 1R44AG032784 (to American Life Science Pharmaceuticals (ALSP)). V.H. holds equity in ALSP and serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of ALSP. The terms of this agreement have been reviewed by the University of California, San Diego, in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. G.H. holds equity in and is employed by ALSP.

Footnotes

For the Special Issue of ‘Biological Chemistry’ of the 6th General Meeting of the International Proteolysis Society, October, 2009, Australia.

References

- Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND, Woessner JR. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. pp. 609–617. [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohme L, Hoffmann T, Manhart S, Wolf R, Demuth HU. Isoaspartate-containing amyloid precursor protein-derived peptides alter efficacy and specificity of potential beta-secretases. Biol. Chem. 2008;389:1055–1066. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Wang Y, McCarthy D, Wen H, Corchelt DR, Price DL, Wong PC. BACE 1 is the major ß-secretase for generation of Aß by neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:233–234. doi: 10.1038/85064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow VW, Mattson MP, Wong PC, Gleichmann M. An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung AY, Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Selkoe DJ. Mutation of the ß-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases ß-protein production. Nature. 1992;360:672–674. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodart JC, Mathis C, Bales KR, Paul SM. Does my mouse have Alzheimer's disease? Genes Brain Behav. 2002;1:142–155. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2002.10302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn BM, Hung S. The two sides of enzyme-substrate specificity: lessons from the aspartic proteinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1477:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efthimiopoulos S, Vassilacopoulou D, Rippellino JA, Tezapsidis N, Robakis NK. Cholinergic agonists stimulate secretion of soluble full-length amyloid precursor protein in neuroendocrine cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8046–8050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner G, Kelly RB. Two distinct intracellular pathways transport secretory and membrane glycoproteins to the surface of pituitary tumor cells. Cell. 1982;28:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata-Fukae C, Sidahmed EH, Gooskens TP, Aisen PS, Dewachter I, Devijver H, Van Leeuven FV, Matsuoka Y. Beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE1)-mediated changes of endogenous amyloid beta in wild-type and transgenic mice in vivo. Neursosci. Letters. 2008;435:186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook VYH, Toneff T, Aaron W, Yasothornsrikul S, Bundey R, Reisine T. β-amyloid peptide in regulated secretory vesicles of chromaffin cells: evidence for multiple cysteine proteolytic activities in distinct pathways for β-secretase activity in chromaffin vesicles. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:237–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook G, Hook VY, Kindy M. Cysteine protease inhibitors reduce brain beta-amyloid and beta-secrease activity in vivo and are potential Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Biol. Chem. 2007a;388:979–983. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook V, Kindy M, Hook G. Cysteine protease inhibitors effectively reduce in vivo levels of brain beta-amyloid related to Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Chem. 2007b;388:247–252. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook V, Kindy M, Hook G. Inhibitors of cathepsin B improve memory and reduce beta-amyloid in transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice expressing the wild type, but not the Swedish mutant, beta-secretase site of the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008a;283:7745–7753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook V, Kindy M, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Hook G. Genetic cathepsin B deficiency reduces beta-amyloid in transgenic mice expressing human wild-type amyloid precursor protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;386:284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook V, Schechter I, Demuth HU, Hook G. Alternative pathways for production of beta-amyloid peptides of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Chem. 2008b;389:993–1006. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook VYH, Toneff T, Aaron W, Yasothornsrikul S, Bundey R, Reisine T. Beta-amyloid peptide in regulated secretory vesicles of chromaffin cells: evidence for multiple cysteine proteolytic activities in distinct pathways for beta-secretase activity in chromaffin vesicles. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:237–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook V, Toneff T, Bogyo M, Greenbaum D, Medzihradszky KF, Neveu J, Lane W, Hook G, Reisine T. Inhibition of cathepsin B reduces beta-amyloid production in regulated secretory vesicles of neuronal chromaffin cells: evidence for cathepsin B as a candidate beta-secretase of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Chem. 2005;386:931–940. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapmanm P, Nilson m S., Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain I, Powell D, Howlett DR, Tew DG, Meek TD, Chapman C, Gloger IS, Murphy KE, Southan CD, Ryan DM, et al. Identification of a Novel Aspartic Protease (Asp 2) as β-Secretase. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1999;14:419–427. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly-Tornetta C, Gao ZY, Lee VM, Wolf BA. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein secretion by glutamate receptors in human Ntera 2 neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;272:140015–140021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.14015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DM, Felsenstein KM, Brenneman DE. Cathepsins B and L differentially regulate amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2009;328:813–821. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Koelsch G, Wu S, Downs D, Dashti A, Tang J. Human aspartic protease memapsin 2 cleaves the beta-secretase site of beta-amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1456–1460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th W.H. Freeman; New York: 1999. pp. 691–726. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Bolon B, Kahn S, Bennet BD, Babu-Khan S, Denis P, Fan W, Kha H, Zhang J, Gong, et al. Mice deficient in BACE 1, the Alzheimer’s ß-secretase, have normal phenotype and abolished ß-amyloid generation. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:231–232. doi: 10.1038/85059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E. Genetically altered transgenic models of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2000;59:175–183. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConlogue L, Buttini M, Anderson JP, Brigham EF, Chen KS, Freedman SB, Games D, Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Zeller M, et al. Partial reduction of BACE1 has dramatic effects on Alzheimer plaque and synaptic pathology in APP transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:26326–2334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Steiner S, Zhou Y, Arai H, Roberson ED, Sun B, Chen J, Wang X, Yu G, Esposito L, Mucke L, et al. Antiamyloidogenic and neuroprotective functions of cathepsin B: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2006;51:703–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EJ, Griasnti JS, Bentley GV, Murray SS. E64d, a membrane-permeable cysteine protease inhibitor, attenuates the effects of parathyroid hormone on osteoblasts in vitro. Metabolism. 1997;46:1090–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitomi K, Sakaguchi G, Horikoshi Y, Gary AJ, Maeda M, Hirata-Fukae C, Becker AG, Hosono M, Sakaguchi I, Minami SS, et al. BACE1 inhibition reduces endogenous Abeta and alters APP processing in wild-type mice. J. Neurochem. 2006;99:1555–1563. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch RM, Slack BE, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH. Release of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor derivatives by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1992;258:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.1411529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch RJ, Farber SA, Growdon JH, Wurtman RJ. Release of amyloid beta-protein precursor derivatives by electrical depolarization of rat hippocampal slices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5191–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Sisodia SS. Mutant genes in familial Alzheimer's disease and transgenic models. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1998;21:479–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberds SL, Anderson J, Basi G, Bienkowski MJ, Branstetter DG, Chen KS, Freedman SB, Frigon NL, Games D, Hu K, et al. BACE knockout mice are healthy despite lacking the primary beta-secretase activity in the brain: implications for Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1317–1324. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Schenk D. Alzheimer’s disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;43:545–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi XP, Chen E, Yin KC, Na S, Garsky VM, Lai MT, Li YM, Platchek M, Register RB, Sardana MK, et al. The pro domain of beta-secretase does not confer strict zymogen-like properties but does assist proper folding of the protease domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10366–10373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m009200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel GJ, Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD. Basic Neurochemistry. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Anderson JP, Barbour R, Basi GS, Caccavello R, Dsavis D, Doan M, Dovey JF, Frigon N, Hong J, et al. Purification and cloning of amyloid precursor protein β-secretase from human brain. Nature. 1999;402:537–540. doi: 10.1038/990114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai M, Matsumoto K, Omura S, Koyama I, Ozawa Y, Hanada K. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of cysteine proteinases by EST, a new analog of E-64. J. Pharmacobiodyn. 1986;9:672–677. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.9.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezapsidis N, Li H-G, Ripellino JA, Efthimiopoulos S, Vassilacopoulou D, Sambamurti K, Toneff T, Yasothornsrikul S, Hook VYH, Robakis NK. Release of nontransmembrane full-length Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein from the lumenar surface of chromaffin granule membranes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1274–1282. doi: 10.1021/bi9714159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towatari T, Nikawa T, Murata M, Yokoo C, Tamai M, Hanada K, Katunuma N. Novel epoxysuccinyl peptides, a selective inhibitor of cathepsin B, in vivo. FEBS Lett. 1991;280:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RS. Alzheimer's disease. Semin. Neurol. 2006;26:499–506. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, 3rd, Koelsch G, Hong L, Castanheira P, Ermolieff J, Ghosh AK, Tang J. Subsite specificity of memapsin 2 (beta-secretase): implications for inhibitor design. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10001–10006. doi: 10.1021/bi015546s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Bennet BD, Babu-Khan S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, Teplow DB, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, Luo Y, et al. ß-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2004. pp. 480–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Kaji T, Tomoo K, Ishida T, Inoue M, Murata M, Kitamura K. Crystallization and preliminary x-ray study of the cathepsin B complexed with CA074, a selective inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;227:942–944. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90234-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Bienkowski MJ, Shuck ME, Miao H, Tory MC, Pauley AM, Brashier JR, Stratment NC, Mathews WR, Buhl AE, et al. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;402:533–537. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]