Abstract

Aim

To develop a management strategy (rehabilitation programme) for erectile dysfunction (ED) after radiotherapy (RT) or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer that is suitable for use in a UK NHS healthcare context.

Methods

PubMed literature searches of ED management in this patient group together with a survey of 28 experts in the management of treatment-induced ED from across the UK were conducted.

Results

Data from 19 articles and completed questionnaires were collated. The findings discussed in this article confirm that RT/ADT for prostate cancer can significantly impair erectile function. While many men achieve erections through PDE5-I use, others need combined management incorporating exercise and lifestyle modifications, psychosexual counselling and other erectile aids. This article offers a comprehensive treatment algorithm to manage patients with ED associated with RT/ADT.

Conclusion

Based on published research literature and survey analysis, recommendations are proposed for the standardisation of management strategies employed for ED after RT/ADT. In addition to implementing the algorithm, understanding the rationale for the type and timing of ED management strategies is crucial for clinicians, men and their partners.

Review criteria

Research articles (from 2000 to 2014) related to erectile dysfunction (ED) management strategies after radiotherapy (RT), brachytherapy (BT) or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer were sought via PubMed and were identified. Search terms used included various combinations of the following terms: penile rehabilitation; erectile dysfunction/erectile function/sexual function + cancer/prostate; sexual dysfunction + cancer/prostate/; erectile dysfunction + radiotherapy/hormonal/androgen; phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor + prostate cancer; vacuum erection device + prostate cancer; alprostadil + prostate cancer; intracorporeal/intracavernosal injections + prostate cancer; erectile dysfunction/sexual function + radiotherapy/androgen + psychosexual/psychological/counselling. An overall evaluation of level of evidence was conducted in developing this review, though most of the studies identified were not based on randomised double blind controlled trials. A survey of 28 experts further provided recommendations on treatment-induced ED management strategies in UK clinical practice.

Message for the clinic

Loss of sexual interest and ED are well-known side effects of RT and ADT. ED prevalence after RT is estimated to be 67–85% and may take up to 24 months to develop. Up to ∽85% of men receiving ADT develop ED. Currently, there are no UK-wide recommendations for post-RT/hormonal therapy erectile dysfunction (ED) management following treatment for prostate cancer. This paper aimed to review the current state of ED management following RT and/or hormonal therapy for prostate cancer, based on a worldwide literature search, to develop guidelines based on available evidence and current clinical practice. The literature review data are supplemented by recommendations from an expert panel – individuals who have used various strategies in their clinical practice- in order to propose evidence-based recommendations for standardised ED management that can be implemented effectively within a publicly funded UK healthcare system.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common male cancer, accounting for 24% of all new cancer diagnoses 1. Men treated for prostate cancer with radiotherapy (RT), including external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) or brachytherapy (BT), have poignantly described the negative impact of erectile dysfunction (ED) on their sense of masculinity and self-esteem 2.

Androgen deprivation therapy can be used in the neo-adjuvant setting, to reduce prostate gland size, in preparation for radical EBRT or BT and in the adjuvant setting, after radical RT, for up to 3 years in men with high risk disease characteristics at presentation 3. ADT is also used as a primary treatment where cancer has spread beyond the prostate or when disease recurrence/progression has been detected 3. ADT can involve orchidectomy, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists and anti-androgens 4. ADT induces a significant reduction in serum testosterone that commonly results in reduced sexual desire and sexual function 5.

Erectile dysfunction in men treated with RT and or ADT is often of multi-factorial aetiology. The precise contribution of physical, psychological and relationship factors arising from the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer, together with any comorbidities, can be complex to determine but should be taken into account when optimising ED assessment and management.

Radiotherapy and erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction prevalence after RT is estimated to be 67–85% and may take up to 24 months to develop 6–8. RT has an impact on vascular structures leading into and within the penis and radiation damage to these structures mediates the decline observed in erectile function (EF) 9. More specifically, endothelial cell damage and microvessel rupture lead to luminal stenosis and arterial insufficiency over a period of months or years after radiation exposure 10.

In an analysis of 16 men who presented with ED after RT for prostate cancer, the mean interval from treatment to ED presentation was 8 ± 5 months after RT 11. These patients had developed cavernosal artery insufficiency and cavernous venocclusive dysfunction 11. RT-induced corporal tissue fibrosis contributes to the development of venous leak which, by definition, is associated with failure to trap blood in the penis and an inability to maintain erectile rigidity 10.

Erectile dysfunction rates vary from 6% to 51% after BT monotherapy, compared to higher rates of 25–89% in men receiving combined BT/EBRT treatment 10. Research by Merrick et al. demonstrated that radiation doses to the proximal penis were predictive of BT-induced ED 12.

Androgen deprivation therapy and ED

The main goal of ADT is to block the interaction between androgens and the prostate. The most commonly used therapeutic strategy is to decrease testosterone production by means of medical castration 4, in two forms: LHRH analogues (e.g. leuprolide, goserelin, triptorelin or histrelin), and GnRH antagonists (e.g. degarelix) 4. Anti-androgens (bicalutamide) can be used in combination to achieve combined androgen blockade either as first-or second-line therapy or as monotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer 13.

Loss of sexual interest and ED are well-known side effects of ADT and are usually attributed to the decrease in testosterone levels 14. EF, while not solely dependent on serum testosterone levels, is usually affected in ∽85% of men receiving ADT 15. It has been suggested that the testosterone threshold value below which EF is affected is about 10% of the normal range of testosterone and that below this threshold value, EF is affected in a dose-dependent fashion 14.

After prolonged ADT (> 3 months) there is generally a decrease in nocturnal penile tumescence in terms of frequency, degree of rigidity, duration and volume of erection 16. ADT indirectly impacts penile smooth muscle structures through this reduction in penile erections. In the absence of erections cavernosal oxygenation is diminished and smooth muscle cells are then exposed to a prolonged hypoxic environment 14,17.

Delayed orgasm or inability to attain orgasm and reduced orgasmic intensity are also common sexual consequences among patients receiving ADT, with men experiencing both lower penile vibratory thresholds and decreased penile sensitivity 15.

Reduced sexual interest can result in withdrawal of emotional and physical intimacy and may result in significant partner distress 18,19. Indeed, loss of the internal drive to seek sexual stimuli and arousal, changes in orgasm and reduced sexual satisfaction are often described by couples as the most disconcerting sexual side effects of ADT 15.

As well as muting biological libido and sexual motivation 15, ADT can also lead to indirect effects on sexual function and masculinity that include gynaecomastia, weight gain, vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes), fatigue and decrease in testicular and penile size 20,21.

Men undergoing ADT often experience reduced muscle mass and physical activity which can lead to adverse effects such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, depression and anxiety 22–26 and further contribute to a reduced quality of life (QoL) 27,28. Generally, < 20% men undergoing ADT maintain any sexual activity 29.

Combined RT and ADT

Androgen deprivation therapy has been shown to exert a detrimental effect on EF particularly when it is combined with RT 10.

In a study assessing the EF outcomes in 482 men with prostate cancer who were potent before treatment, the 5-year actuarial potency of BT patients was significantly worse when neo-adjuvant ADT had been given (76% vs. 52%). In this study, potency was defined as the ability to achieve an erection sufficient for penetration during intercourse without medications or devices 30. In the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results programme, it was shown that 69% of the men who were potent before ADT treatment lost their potency after treatment, though there were not any significant differences in rates of ED between the types of ADT therapy 29.

Decreased penile length after RT plus neo-adjuvant or adjuvant ADT has also been observed and men should be informed before treatment that penile shortening can occur 31.

Men receiving combined RT and ADT who have co-morbid conditions that may impact on their erectile recovery require a holistic approach to the assessment and management of their ED. Pre-existing comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension or cardiovascular disease; certain prescribed or recreational drugs and psychosocial factors can also affect pretreatment sexual function 32. Indeed, the two most important predictive factors for ED following ADT were age > 70 and the presence of diabetes mellitus 33.

Similar to men undergoing surgery for prostate cancer, baseline EF remains an important predictor of posttreatment EF 34. It is therefore important to manage patient and partner expectations as baseline EF and subsequent recovery rates for EF in this sub-group of men is usually lower than that seen after radical prostatectomy (RP).

These factors must be taken into account in the assessment and management of ED in this group of men. Furthermore, as ADT duration can range from months to years, men and their partners need to understand and recognise the potential effects of treatment on their sexual lives as a lack of preparation for such sexual changes often results in regret, anger or depression 29.

The goal of EF management strategies in men undergoing RT and/or ADT is, therefore, the restoration or maintenance of assisted and non-assisted EF and prevention of both RT and ADT-induced structural changes in the penis.

The benefits of early sexual rehabilitation interventions may not be immediately apparent to men with low sexual interest or delayed development of ED. It is therefore especially important for clinicians to clearly communicate the rationale behind any EF restoration programme 10 and to make men aware that EF will not usually recover spontaneously while ADT is ongoing in the adjuvant setting.

The current options for ED management in the UK include:

Oral medication [phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5-Is: sildenafil, tadalafil or vardenafil)]

Intracorporeal/intracavernosal injections (ICI)

Intraurethral suppository containing alprostadil

Vacuum erection device (VED)

Psychosexual therapy or sexual counselling

Pelvic floor exercises

Combinations of the above

Penile implant: malleable or inflatable as a remaining option

However, most of these treatment options for ED have not been extensively studied in patients undergoing or having undergone RT/ADT and therefore, the recommendations summarised in this article are based, to a greater extent, on clinical practice rather than definitive literature analysis.

Rationale for development of recommendations

With increased detection of cancer, earlier diagnosis and improved treatments the number of people surviving cancer is growing. Consequently there is increased emphasis on QoL, a component of which is sexual function. External beam RT, BT and ADT have an adverse impact on the patient's QoL, especially in men with good pretreatment sexual function. Currently, there is no consensus regarding the diagnosis and management of sexual dysfunction in these patients.

The underlying goal of an EF restoration programme is to replicate the normal physiological conditions of the penis as much as possible using pharmacological manipulation combined with psychosexual therapy to preserve healthy erectile tissue and maximise the potential of mens’ future ability to achieve erections without therapy. This article aims to evaluate the EF restoration strategies for ED following radiation/hormonal treatments to propose evidence-based recommendations for standardised ED management that can be implemented effectively throughout the UK.

Stember and Mulhall recently provided recommendations for treating ED after RT/ADT, extrapolating results from post-RP patients and applying similar recommendations to RT/ADT patients 10. In our review, however, we have excluded post-RP literature given that this is the subject of another recent publication 35. In addition, the physiology of ED after RT/ADT is different from that after surgery and management of the condition has to reflect this. Here, we focus on RT/ADT literature as well as utilising clinical experience from a survey of UK clinical oncology, uro-oncology and ED service specialists, including consultants, specialist urology and uro-oncology nurses and psychosexual therapists working in cancer care.

Methods

Literature analysis

A review of published literature was carried out to determine current management options for ED following RT/ADT and establish the evidence grade for each option. The studies identified and used in this literature analysis were graded using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence 36.

Search terms used included various combinations of the following terms: penile rehabilitation; erectile dysfunction/erectile function/sexual function + cancer/prostate; sexual dysfunction + cancer/prostate/; erectile dysfunction + radiotherapy/hormonal/androgen; phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor + prostate cancer; vacuum erection device + prostate cancer; alprostadil + prostate cancer; intracorporeal/intracavernosal injections + prostate cancer; erectile dysfunction/sexual function + radiotherapy/androgen + psychosexual/psychological/counselling.

Reviews (except systematic reviews), commentaries and animal studies were excluded. Any studies which did not utilise RT/BT/ADT for the treatment of prostate cancer were excluded. RCTs evaluating the effectiveness of interventions following RP were excluded unless the surgery had occurred at least 5 years before RT or hormone therapy. All studies analysed used at least one intervention for ED management (studies from 2000 to 2014 included; Search carried out January 2014).

Specialists’ survey

The recommendations from clinical practice were gained by conducting a survey with 28 experts representing current practice across the UK. The survey investigated current practice in ED assessment and management after RT/hormonal therapy in prostate cancer patients, focusing on questions related to current clinical practice; scope of the problem in the UK and treatment approaches.

Results

Literature search overview

The literature search identified 19 articles after applying the selection criteria. Both randomised and non-randomised studies were included (Table1). Eleven of the studies selected were not based on randomised double-blind controlled trials.

Table 1.

Study and patient characteristics of articles selected for literature review

| Study | Level of evidence | No. of patients | Study design | Regimen | Start of treatment (after RT/BT/ADT) | Duration (D) /follow-up (F) (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE5-Is) | ||||||

| Zelefsky et al. 37 | 1B | 279 | Randomised study | Daily sildenafil (50 mg) or placebo | 3 days pretreatment | D 26 weeks F 104 weeks |

| Ilic et al. 38 | 1B | 27 | RCT | Daily sildenafil or placebo | 4 weeks | D 26 weeks F 104 weeks |

| Yang et al. 39 | 2A | N/A | Systematic review | Efficacy of PDE5-Is (various regimens) | N/A | N/A |

| Watkins Bruner et al. 40 | 1B | 115 | RCT | On demand sildenafil (50–100 mg) or placebo | 26 weeks–5 years | D 25 weeks F 25 weeks |

| Pahlajani et al. 41 | 4 | 69 | Case series | Early (immediately after BT) vs. no treatment with PDE-5-I | Immediately after BT for 52 weeks | D 52 weeks F 52 weeks |

| Ricardi et al. 42 | 1B | 86 | RCT | On demand 20-mg tadalafil vs. tadalafil 5-mg once-a-day dosing | 26 weeks | D 12 weeks F 12 weeks |

| Teloken et al. 43 | 2B | 152 | Cohort study | None – based on enrolling patients who met certain criteria including sildenafil use | ∽22 weeks | 3.2 years |

| Candy et al. 6 | 2A | 959 | Systematic review | N/A (included 5 RCTs) | 26 weeks–4.5 years | F 6–16 weeks |

| Incrocci et al. 44 | 1B | 51 | Open-label extension after RCT | Tadalafil 20 mg or placebo and then crossed over, followed by open-label extension phase |

52 weeks | D 18 weeks F 18 weeks |

| Teloken et al. 45 | 4 | 152 | Case series | None – based on enrolling patients who met certain criteria including sildenafil use | 26 weeks–3 years | 3 years |

| Incrocci et al. 46 | 1B | 60 | Single-centre randomised controlled cross-over trial | Tadalafil 20 mg or placebo on demand then patients crossed over | 52 weeks | D 12 weeks F 12 weeks |

| Schiff et al. 47 | 4 | 210 | Case series | PDEIs at < 1 year (early group) or > 1 year after BT (late group) | 27 weeks in early and 85 weeks in late group | 1.5–3 years |

| Ohebshalom et al. 48 | 4 | 110 | Case series | Sildenafil | 35 ± 16 weeks | 3 years |

| Incrocci et al. 49 | 1B | 60 | Open-label phase of 2001 double-blind (DB) study | 50 mg of sildenafil, increasing dose to 100 mg | 3.3 years | D 18 weeks F 104 weeks |

| Incrocci et al. 50 | 1B | 60 | Single-centre randomised controlled cross-over trial | On demand sildenafil (50–100 mg) or placebo | 3.3 years | D 12 weeks F 12 weeks |

| Sexual counselling | ||||||

| Forbat et al. 51 | 4 | 60 | Case series | Clinical consultation observation | N/A | N/A |

| Canada 52 | 1B | 84 | Randomised study | The efficacy, with or without the attendance of a female sexual partner, of sexual counselling | 13 weeks–5 years | D 26 weeks F 26 weeks |

| Lifestyle interventions | ||||||

| Cormie et al. 53 | 1B | 57 | Randomised controlled trial | Exercise programme vs. usual care | While on ADT | D 12 weeks F 12 weeks |

Studies and patient characteristics from the literature analysis

Of the 4062 patients included in the 19 selected studies (Table1). Most of the studies were non-randomised uncontrolled studies. Follow-up (F) ranged from 4 weeks up to ≥ 3 years while ED management duration (D) ranged from 6 weeks to 52 weeks (Table1).

No studies were identified that evaluated the use of VED, intraurethral alprostadil or ICI for men with ED following RT/ADT.

Trial participants were adult males (aged 16 years or over), receiving any RT/hormonal therapy (or who had previously received any) for prostate cancer, and who had experienced any type of ED (however identified) subsequent to their RT/hormonal therapy.

Pretreatment assessment

Partner involvement

Importance of patient and partner involvement in assessing ED prior to treatment has been shown in a previous review of patients after RP 35 and will not be discussed in detail here. Many clinicians are aware that both patient and partner-related factors are important to sexual recovery 54 following treatment for prostate cancer. Men and their partners want to be informed and involved in making decisions with regard to their cancer treatment and management of ED 9,55.

A study of 60 consultations between clinicians, patients and partners showed that sexual functioning was discussed infrequently and, despite the presence of partners in nearly half of consultations, involvement of the partner tended to be minimal 51. Overall, there were limited opportunities in routine follow-up clinics for couples to discuss the specific impact of prostate cancer and its treatments on sexual functioning 51.

A Canadian Working Group that evaluated interventions to limit the physiological and emotional difficulties experienced by men and their partners after ADT recommended providing information about ADT side effects before administration of ADT and, where appropriate, providing referrals for psychosocial support 15. These recommendations included offering psychological interventions for sexual sequelae to men and their partners 15.

In our clinician survey, approximately 89% of the expert respondents agreed that involving partners was beneficial when assessing and managing patients’ ED, though they would only involve partners if they attended consultations with patients. However, only 36% of participants routinely involved partners in practice and 11% of respondents either did not feel that involving the partner was important or never had an opportunity to involve partners, suggesting that professional opinion did not always translate into clinical practice. The remaining respondents (53%) did not answer this question in the survey.

Baseline assessment of EF

Approximately 67% of participants reported not having any system/guidance in place for assessment and management of patients with ED prior to RT or ADT. Approximately 50% of the participants would discuss these additional assessments with the patient and ∽50% would alter their ED management plan based on findings from these assessments.

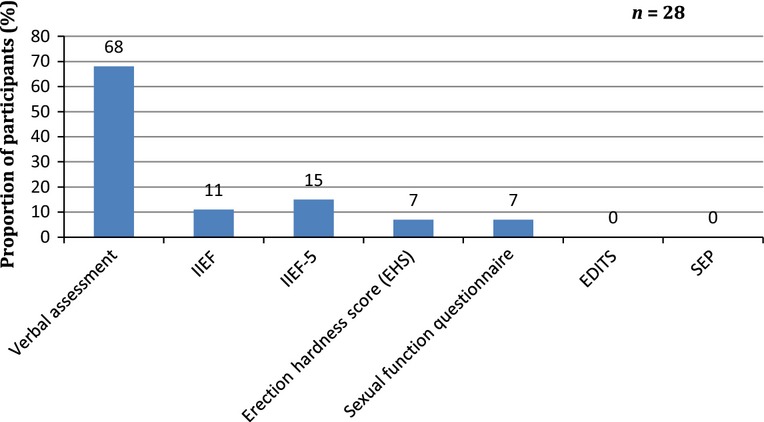

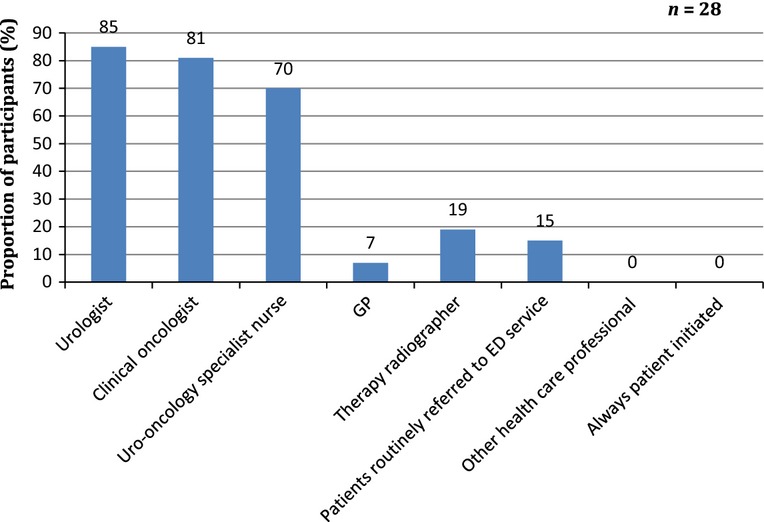

Fifty per cent of survey participants confirmed that they performed a baseline sexual function assessment before radical RT or hormone therapy for prostate cancer. Of the participants who did assess their patients pretreatment, most relied on verbal assessment (Figure1). The survey further demonstrated that ≥ 90% of ED discussions were generally initiated by the clinician rather than the patient. The majority of participants believed that it should be the urologist or the oncologist who should initiate a discussion regarding ED with the patient. Other health professionals deemed appropriate to initiate this discussion included specialist nurses, radiographers or the patient's GP (Figure2).

Figure 1.

Baseline assessment tools used by survey participants

Figure 2.

Who initiates ED discussion with patients?

Most participants agreed that all patient groups should be assessed for ED. However, three participants stated that they would not consider assessing elderly men (though the term ‘elderly’ was not defined), one participant stated that they would not assess men disinterested in sexual activity and one participant stated that they would not assess men with dementia. Furthermore, 50% of participants agreed that the duration of ADT would not influence their decision to discuss ED with the patient, i.e. whether it was long-term or short-term therapy, they would still consider talking to the patient about it. However, some participants believed that PDE5-Is did not elicit a response after long-term ADT and, with these men, other treatments should be discussed such as VED as well as sexual counselling with the aim to improve sexual desire/interest and provide individual/couple support.

All participants indicated that they would initiate discussions about ED prior to RT or ADT to sufficiently prepare men for ED or loss of sexual desire/interest.

Generally, the following factors (in order of importance as rated by the participants) should be assessed before treatment as these factors are likely to affect EF posttreatment:

Comorbidities, e.g. cardiovascular disease.

Current medication e.g. nitrates, antihypertensives, antidepressants.

General lifestyle factors e.g. smoking, obesity, exercise.

Metabolic status.

Almost all of the participants stated that there was a checklist in their practice for assessing the factors stated above before initiating treatment.

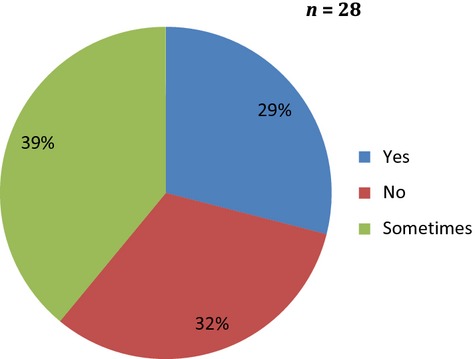

Baseline assessment of testosterone levels

Most participants only occasionally measured testosterone levels before ADT (Figure3). Testosterone levels were not routinely checked in clinical practice before or after ADT therapy unless there was a clear indication to do this.

Figure 3.

Do you measure testosterone levels at baseline and after ADT?

Time elapsed from treatment to assessment/management of ED

According to the literature analysis, the length of time from treatment to initiation of ED management varied from immediately after ADT/RT treatment or during treatment to up to 5 years after treatment. However, improved outcomes were observed with earlier ED management (immediately or within 6 months posttreatment) following BT 41,47. An early vs. late ED management comparison was not found in the literature analysis for ADT.

In the expert panel survey, most participants believed that initiation of ED management was the responsibility of a dedicated ED specialist nurse or urologist, potentially resulting in management delay due to the need for specialist referral and limited access to specialist ED services. It is also noteworthy that most participants would prescribe PDE5-Is if the patient presented with ED, though would consider referral to an ED clinic if the PDE5-Is did not work. Sildenafil was noted as the PDE5-I of choice as it is now available as a more cost-effective generic formulation and its use is no longer under current UK NHS ED drug prescribing restrictions. Most participants also agreed that follow-up and monitoring of response to ED management strategies could be the responsibility of the GP or the ED clinic and that a GP should be involved in all treatment regarding patients’ ED. Evaluation of ED treatment efficacy was usually recommended by participants at 3 months after initiation of management and at three monthly intervals thereafter.

Posttreatment ED management

Current availability of NHS UK management strategies for patients after RT/BT/ADT

Current management strategies and their efficacy/tolerability data from the literature analysis for ED are summarised in Table2.

Table 2.

Current management strategies for ED after RT/ADT from literature analysis

| Strategy | No. of publications | Total no of patients | Results | Adverse events | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative management (exercise programme) | 1 | 57 | Significant (p > 0.045) difference in sexual activity following 12-week short-term exercise programme 53 Patients undergoing usual care decreased sexual activity while patients in the exercise programme maintained their level of sexual activity 53 Following the intervention, the exercise group had a significantly higher percentage of participants reporting a major interest in sex (exercise > 17.2% vs. control > 0%; p > 0.024) 53 |

N/A | Short/long term exercise programme improves and maintains EF and improved libido |

| Psychosexual Counselling and Therapy | 3 | 144 | Improved outcomes observed with sexual counselling in men and women with/without partners 52 Sexual functioning is discussed infrequently in routine FUP 51 Despite the presence of partners in nearly half of consultations, involvement of the partner tended to be minimal 51 |

N/A | Sexual counselling improved ED outcomes for patients and partners Partner involvement in clinical discussions are minimal |

| Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE5 I) | 15 | 3532 | Efficacious after RT and BT but ADT diminished response to PDE5-I 6,37–39,43–46,49 Better patient satisfaction at 24 months with daily sildenafil 37 Optimal response achieved when PDE5-I initiated 12–24 months after RT 6,41 Significantly better IIEF-5 scores up to 6 months with daily sildenafil after RT, though scores diminished when medications stopped 38 Sexual desire scores remain high up to 24 months after daily sildenafil despite discontinuing treatment 37 Significant increase in mean scores with on demand sildenafil for up to 2 years 43,49 Significantly better IIEF scores with tadalafil after RT over 12 weeks 44,46 Approximately 50% reported successful intercourse with tadalafil (placebo: 9%) (p < 0.0001) over 12 weeks after RT 46,50 The response to PDE5-I treatment is time dependent with a stepwise decrease in all end points examined serially in a 3-year period 43,48 Early use of PDE-5i after BT maintains EF up to 36 months 41,47 No difference between on demand vs. daily use after RT 42 Significantly more functional erections vs. placebo at 24 months despite discontinuing daily sildenafil at 6 months 37 Better compliance observed with once daily dosing 42 Predictors of poor response: older age, longer time after RT, ADT > 4 months duration and RT dose > 85 Gy 43 ADT seems to exert a deleterious effect on PDE5-I response in men undergoing RT 37,47 |

Mild-to-moderate headaches or facial flushing 37,46,49,50 | PDE5-Is are efficacious after RT/BT but their effect can be diminished after ADT Initiating PDE5-I within 1 year of RT correlates with better outcomes Daily therapy associated with better outcomes in the short and long term and on demand therapy associated with better outcomes in the long term Daily dosing associated with better compliance Time-dependent response |

Clinical practice: current management strategies for patients after RT/ADT from expert panel survey

Immediate referrals: According to our survey, 21% of participants stated that they would refer patients suffering from ED immediately to a specialist ED clinic without initiating any treatment themselves.

-

Assessment: A further 29% of participants would assess patients as follows:

Routine blood tests (fasting blood glucose, free testosterone levels; vascular risk factors, etc.).

Lifestyle assessment and advice regarding smoking, increased alcohol intake, obesity.

Assess whether the issue is low sexual interest / desire due to ADT or ED or both.

Appropriate management options would only be considered by these participants after the aforementioned assessments are completed.

Patient involvement in treatment decision: Only two participants stated that they would discuss treatment options with the patient before prescribing.

Short vs. long term ADT: Approximately 61% of the participants stated that they would employ the same treatment for short- and long-term ADT patients. Three participants believed that ED may improve spontaneously after stopping hormones, so there was no need to prescribe any ED treatment. The impact of short vs. long term ADT and role of testosterone are considered further in the discussion section below.

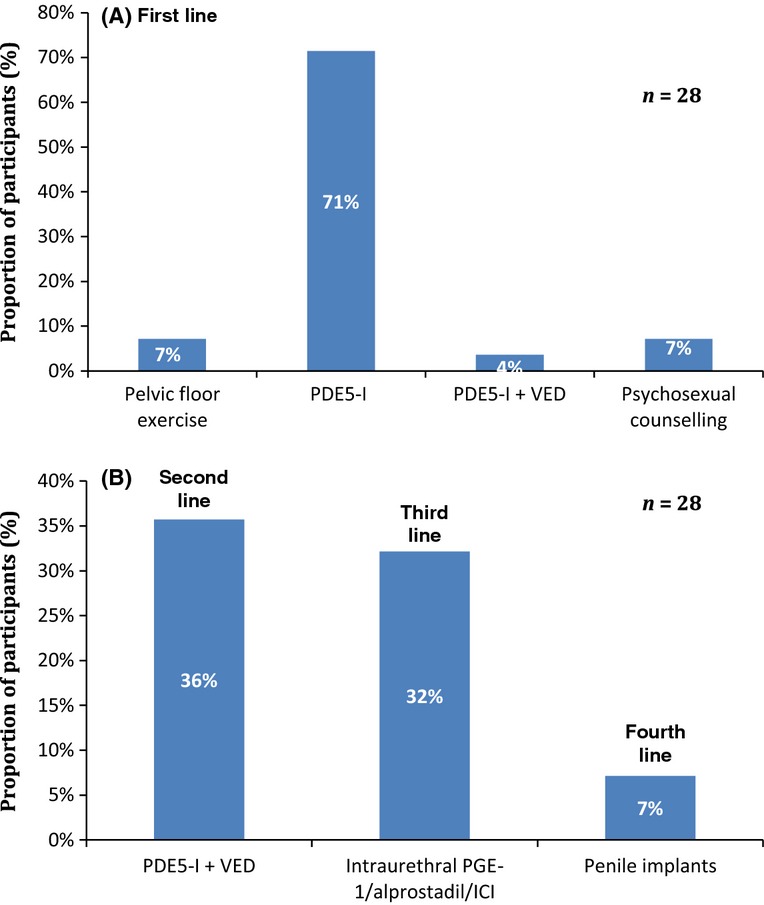

ED treatment options: These were outlined by the participants as per Figure4A, B.

Figure 4.

Survey results reflecting current ED management after RT/BT/ADT: (A) First-line management and (B) subsequent management in specialist ED clinic

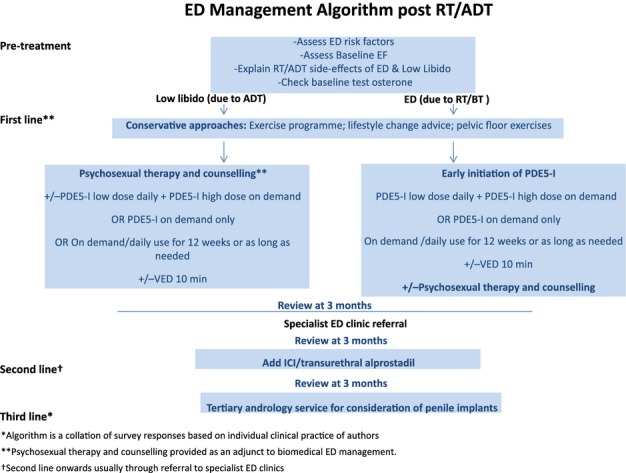

ED management algorithm

A typical management algorithm employed in clinical practice by the majority of survey participants for ED post-RT/BT/ADT is shown in Figure5. This algorithm is mainly based on locally agreed practice and not any specific existing national/international guidelines.

Figure 5.

Recommended management algorithm for ED post-RT/BT/ADT. *Algorithm is a collation of survey responses based on individual clinical practice of authors. **Psychosexual therapy and counselling provided as an adjunct to ED treatment. †Pelvic floor exercise advice also provided by physicians

Cost-effective ED management strategy in clinical practice

Most participants expressed uncertainty over the most cost-effective strategy for managing ED after RT/BT/ADT. However, PDE5-I use was rated as the most cost-effective strategy (by 20% of the participants) compared with VED or combination strategies. The participants stated that the reason they thought oral PDE5-Is were the most cost-effective strategy was because they generally worked well for patients and there was no need for onward referral to ED clinics. As sildenafil is now off patent it can be obtained for less than £1/pill.

The most effective strategy depended on patient and partner needs, e.g. low sexual desire may require psychosexual therapy or counselling in addition to PDE5-Is. However, the most commonly favoured combination was VED + PDE5-I (daily or/and on demand). Weekly timetabled sexual activity may also be an option to help couples manage reduced libido.

Follow-up and monitoring

-

Follow-up assessment: Only 32% of participants stated that they would assess ED at all follow-up appointments, whereas approximately 39% of the participants reported that they would not do so. The remaining participants would only assess ED if directed by the patient.

Follow-up assessments generally comprised informal verbal assessment or formal score-system based assessments if carried out within ED clinics.

Monitoring responsibility: As many as 96% of the participants believed that monitoring and follow-up assessments of ED were the responsibility of uro-oncology or ED specialist nurses.

Initial monotherapy strategy success rate: Initially the majority of patients were treated with PDE5-I monotherapy. The success rate, as reported in our survey, varied from 25% to 95%, with most participants reporting a success rate of ˜50%. However, participants felt that the success rate with PDE5-Is was difficult to quantify accurately in clinical practice.

Duration of treatment

In the literature analysis the duration of ED management lasted from 6 weeks up to ≥ 3 years’ posttreatment completion.

According to the survey findings, the duration of any treatment ranged from 3 months until the patient no longer needed ED management. The duration of any management strategy probably depends on the underlying cause of ED and hence individualised management in this patient population is very important. Furthermore, the decision to stop ED treatment must be individualised as strict time limits are considered inappropriate.

Discussion

The literature search identified 19 randomised and non-randomised studies. Most studies identified were non-randomised or controlled studies. Findings from both the literature analysis and our clinician survey indicated that resolving ED can improve men's QoL.

Assessment of erectile function

Men and their partners should be counselled prior to commencement of ADT/RT to prepare them for treatment related sexual side effects including ED and loss of sexual interest. Pretreatment EF should be assessed and recorded.

However, involvement of partners at assessment, while recommended in the literature and acknowledged by all clinicians surveyed, depended on patient agreement and presence of partners during clinical consultations.

Predictive factors

The recovery of EF is a multi-factorial process that depends on many variables identified within the literature review and through our clinician survey. These include:

Patient and partner age

Pretreatment EF and sexual activity level

Metabolic status

Cardiac/cardiovascular function

Other comorbidities in the patient/partner

Current medications

General lifestyle factors, e.g. smoking, obesity, exercise, etc.

Testosterone levels – normal levels are important for recovery of EF

The period of time taken for testosterone levels to return to normal after stopping ADT

Management of erectile dysfunction

Goals of ED management/restoration of EF after RT/BT/ADT

All participants in the healthcare professional survey agreed that the goals for managing ED post-RT/BT/ADT should be:

Achievement/restoration of EF at a level satisfactory to patient/couple or to pretreatment level

Restoration or maintenance of EF sufficient for successful penetrative intercourse

Maintain sexual function and penile length

Improve patient's QoL and sexual self-esteem

Reduce anxiety levels associated with sexual intimacy

Compared with RP patients, RT patients may be less motivated initially to start or remain compliant with a sexual rehabilitation regimen 10, especially as the addition of ADT will normally reduce sexual interest and drive. In addition, there is a delayed (up to 2 years following end of RT and up to 12–18 months after cessation of ADT) pattern of ED development/EF recovery. This differs from men after RP who do not have neo-adjuvant ADT. Therefore, it is essential that the rationale for EF restoration is communicated clearly to them. Clinicians should offer men written information about the immediate and longer term impact of RT/ADT on their sexual lives and aim to discuss these anticipated changes with men and their partners. Whenever possible, partners should be included in ED management decisions, as they can be significantly affected by treatment side effects 15,56. The advantages and disadvantages of ED management options should be discussed with the patient and his partner (Table3) 56. It is particularly important to note that the delayed penile structural changes created by RT necessitate early intervention to try to preserve EF and reduce impact of RT-induced fibrosis. Indeed evidence suggests that PDE5-Is are efficacious if initiated within 1 year of RT and that response to these medications appears to be time dependent (Table2). In addition, longer term ADT is associated with worse outcomes, so for patients on long term ADT, other factors such as testosterone levels, and exercise programmes should be discussed during initial assessment and patient/couple's expectations are managed.

Table 3.

Advantages and disadvantages for each RT/BT/ADT ED management strategy

| Post-RT/BT/ADT ED management strategy | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative management (exercise programme) | Short/long term exercise programme improves/maintains EF and improves libido and supports weight management as obesity is an independent risk factor for ED | N/A |

| Psychosexual Therapy and Counselling | Improves EF outcomes for men and partners Support couples to adopt non-coital alternatives where ED is non-responsive to biomedical management strategies |

N/A |

| Oral medications (PDE-5I) | Easy to take Acceptable to most men and partners Good tolerance generally Does not interfere with foreplay Efficacious after RT/BT Initiating within 1 year of RT correlates with better outcomes |

Possible drug interactions and relative contraindications in men with comorbidities/nitrate use Diminished effect after ADT (especially long term ADT) Time-dependent response |

| Vacuum erection device | Avoids medication – may be more acceptable to some men Non-invasive No systemic effects or medical toxicity Cost-effective Simple to use Improves cavernous oxygenation and helps maintain penile length |

Uncomfortable, clumsy, mechanical Erection does not feel/look natural Need for patient/partner commitment to learn Skilled instructor needed Patient and partner acceptance required If used for penetration: can be altered penile sensation |

| Intraurethral suppository | Relatively easy to learn to use Rapid onset No needles Painless to insert Well-tolerated Local treatment |

Can be difficult to insert Urethral ‘stinging’ May not be effective for all men |

| Intracavernosal injections | More natural looking erection Quick administration and result Usually effective – direct drug delivery |

Possible issue with patient compliance Not acceptable to all men or their partners Good manual dexterity needed Skilled instructor needed Patient (& health professional) fear of priapism Pain and bruising Penile fibrosis at injection site |

| Combination strategy | May be helpful for those with diminished response to PDE5-Is alone Problems as above with differing combinations therefore additive |

Need for more than one intervention Patient commitment Expensive and time consuming Variation in availability across different centres/hospitals in the UK |

Oral therapy – PDE5-I

As with patients after RP, the first-line treatment for RT/ADT-induced ED is PDE5-Is, although both clinical opinion and published research indicate that these agents usually have reduced efficacy in men receiving ADT 57.

There is good evidence, from placebo-controlled randomised trials, that PDE5-Is can improve EF in men following RT/BT. Sildenafil 50 and tadalafil 46 have shown effectiveness for the treatment of ED after external beam RT. Incrocci et al. evaluated the effect of 2 weeks on demand sildenafil vs. placebo in 60 men with ED following RT for prostate cancer 50. The starting dose of sildenafil was 50 mg on demand. In most men (90%) this was increased to 100 mg because of an unsatisfactory response at the lower dose. At 6 weeks, participants crossed over to an alternative treatment for a further 2 weeks.

The tadalafil trial evaluated 60 men with ED after RT who were randomised in a cross-over trial to receive either 20 mg of tadalafil or a placebo daily for 6 weeks 46. The duration of follow-up was 3 months and results showed that tadalafil, given after RT, resulted in successful intercourse, which was reported by almost 50% of the patients 46.

After RT, PDE5-Is assist many men to achieve increased rigidity of erections and thereby contribute to periodic arterial levels of penile oxygenation and facilitate sexual activity. Clinical experience suggests that this approach also helps maintain nocturnal and early morning erections. Hence daily PDE5-I treatment would be a logical approach to adopt, albeit with limited research evidence to support regular preventive use at present 37.

Zelefsky et al. 37 recently reported results from the first prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine if daily adjuvant use of sildenafil before, during and after radiation therapy preserved EF 37. The trial randomised 279 men with localised prostate cancer treated with RT (± ADT) to daily sildenafil (50 mg) or placebo (2:1 randomisation).The treatment/placebo were initiated 3 days pre-RT treatment and continued daily for 6 months. At 12 months, EF and sexual satisfaction scores were significantly better than placebo. At 24 months, although EF scores were not significantly better than placebo, the overall sexual satisfaction scores remained significantly higher. At 24 months sexual desire scores were significantly higher than placebo despite discontinuing sildenafil 18 months previously. The results of this study support animal data on the potential vascular protective effect of sildenafil, but further research using a longer duration (> 6 months) of PDE5-I therapy following testosterone recovery is warranted to demonstrate fully the clinical benefits for this group of men 37.

In a prospective study, Schiff et al. reviewed patients who underwent BT and subsequently used PDE5-Is on a regular basis (two to four doses per week of 50 or 100 mg sildenafil) 47. Patients were stratified into an early use group (< 1 year post-BT) and a late use group (> 1 year post-BT). At 6-month intervals, 18–36 months after treatment (time points at which all patients had begun PDE5-I use), Sexual Health Inventory scores were significantly better for men in the early intervention group 47. These data suggest that delaying the start of penile rehabilitation after RT/BT is associated with poorer EF outcomes.

In a study of patients who underwent either BT or EBRT for localised prostate cancer with or without ADT, men who had the combined treatment had lower mean and EF domain scores on the IIEF questionnaire and worse response to sildenafil at multiple time points during the first 3 years posttreatment 45. The percentage of men responding to sildenafil at 24 months post-RT was 61% for those without ADT and 47% for those with ADT (p > 0.032) 45. In terms of ADT, the efficacy of sildenafil was usually poor, as tissue androgenisation is required for optimal response to PDE5-Is 45. Teloken et al. have shown that the efficacy of sildenafil citrate was significantly decreased in men who underwent ADT along with BT compared with BT alone 45. Worse outcomes for combined therapy patients were seen at all posttreatment follow-up time points, ranging from 6 to 36 months 45.

A placebo-controlled cross-over trial 40 in patients treated with EBRT and neo-adjuvant or concurrent ADT found that the sildenafil effect was significant (p > 0.009) vs. placebo. However, only 21% of patients had a treatment-specific response, improving during sildenafil, but not during the crossed-over placebo phase 40.

Testosterone levels

Evidence supports a role for testosterone in response to endogenous vasodilators with the expression and activity of PDE5-Is shown to be under the control of androgens 14. A study by Jannini et al., involving 83 men with ED compared to 30 age-matched controls, found reduced total and free testosterone levels in the former group (both p < 0.001), suggesting lower levels of testosterone are associated with the development of ED 58. A significant increase in serum total and free testosterone levels was observed in those men who achieved normal sexual activity 3 months after commencing ED management (p < 0.001), while serum testosterone levels did not change in the men where ED therapy was ineffective 58.

With the advent of PSA testing and newer agents for prostate cancer, men are remaining on ADT for much longer than might have been originally anticipated 59. The impact of ADT on subjective sexual desire is difficult to evaluate and measure. In the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study, 431 men receiving ADT were examined. Results indicated that 51% of men who were interested in sex before treatment reported ‘no interest’ after ADT and 73% reported cessation of sexual activity following ADT, irrespective of the type of ADT prescribed 29. In contrast, other studies have found no relationship between testosterone levels and sexual desire 60,61. A study by Martinez-Jabaloyas et al. concluded that androgens are ‘necessary but not sufficient’ for normal sexual interest and the testosterone threshold value below which desire is affected remains poorly defined 61. Some authors stress that the testosterone threshold value below which sexual behaviour is affected may vary significantly from one individual to another 14. Wu et al. suggested that hypogonadism in men ≥ 40 year old can be defined by the presence of at least three sexual symptoms (decreased frequency of morning erection, decreased frequency of sexual thoughts and ED) associated with a total testosterone level of less than 11 nmol/l (3.2 ng/ml) and a free testosterone level of less than 220 pmol/l (64 pg/ ml) 62.

A longer duration of ADT results in a decreased likelihood of testosterone level recovery 63–65. Testosterone deficiency is usually a late side effect of radiation therapy 63–65. Most men recover testosterone levels after long term ADT or RT to some extent, depending on their age, but recovery of ‘normal’ testosterone levels is slow and few recover potency and sexual desire 66.

Androgen deprivation alters the functional responses and structure of erectile tissue and this effect has been shown to be reversed in animals given testosterone 67. Furthermore, PDE5-I activity increased in castrated animals treated with testosterone 67. A recent meta-analysis in men with hypogonadism who did not have prostate cancer stated that total T > 12 nmol/l (> 350 ng/dl) does not require replacement therapy, whereas T < 8 nmol/l does merit treatment 68.

Testosterone replacement for men with persistent low desire, total ED and low T levels following RT/ADT for prostate cancer remains highly controversial, especially in higher risk disease. However, the management of low sexual desire and associated sexual distress in testosterone-suppressed men on ADT may benefit from professional psychosexual or psychological therapy according to our survey analysis.

Nevertheless, PDE5-Is given on demand demonstrate modest efficacy in patients with ADT as per our literature analysis. Other erectile aids that are less well studied in the RT/ADT literature include intracavernosal therapy, vacuum devices and penile implants.

VED/PDE5-I + VED combination

No studies were identified which evaluated the use of VED for men with ED following RT/ADT. However, VED has been shown to significantly improve penile oxygen saturation in patients after prostatectomy and may contribute to the maintenance of both penile structure and length 69.

In the survey analysis, only one participant stated that they would consider VED as a first-line option for ED in combination with PDE5-Is. The majority of survey participants believed that VED could be used as a second line option, added to PDE5-I where there is no response to oral drugs after 3 months. Participants also agreed that VED should be initiated in specialist ED clinics to provide patient education and support compliance with device use.

ICI/Intraurethral alprostadil

No studies assessing the efficacy of ICI/intraurethral alprostadil on sexual dysfunction in men treated with RT/BT/ADT were found. In the survey analysis, most participants stated that they would use ICI/intraurethral alprostadil as third line options after failure of PDE5-I monotherapy and PDE5-I + VED combination therapy.

Exercise programmes

Men who undergo ADT could benefit from exercise by reducing risk factors for metabolic complications, therapy-related comorbidities and physical function decline 24.

In a study by Cormie et al. on men undergoing ADT, significant (p > 0.045) benefits in sexual activity were observed following a 12-week short-term exercise programme 53. Improved levels of sexual interest were also observed following the intervention with significantly more participants in the exercise group reporting interest in sex (exercise > 17.2% vs. control > 0%; p > 0.024) 53.

Cormie et al.'s 53 findings are supported by results from a combined resistance/aerobic exercise programme that improved management of ADT side effects and significant improvements in sexual function, fatigue and cognitive function 70.

Psychosexual therapy and counselling

Treatment guidelines from the British Society for Sexual Medicine recommend psychosexual counselling and patient education for patients with sexual dysfunction, but men affected by cancer rarely access such services 15,71.

An RCT of group education for men who had RT for prostate cancer (baseline level of sexual function not assessed) found positive sexual outcomes associated with psycho-educational interventions 54.

The efficacy, of a four session sexual counselling intervention (with female sexual partners included/excluded) was assessed in a pilot RCT in 84 men who had ED as a result of RT or prostatectomy for prostate cancer 52. One group received counselling with their female partners present and the second received counselling without their partner present. The results demonstrated that the presence of a female partner at the counselling sessions did not significantly affect male sexual function and satisfaction 52. However, improved outcomes following sexual counselling for both study groups were observed for male and female participants when compared with baseline.

Hence, referral to appropriate psychological or psychosexual services is important in the management of these men/couples. Sexual counselling, including sufficiently preparing the man and his partner for sexual side effects of their treatment, should ideally be offered before or concurrent with biomedical interventions to be most effective 15.

Surprisingly only 4% of the expert panel surveyed would consider referring this group of men to psychosexual counselling, which may be due to the limited availability of counselling in the NHS. However, counselling along with ED treatment may be important for men receiving ADT, as shown in our algorithm (see Figure5).

ED Management algorithm based on literature analysis and clinician survey findings

Stember and Mulhall provided the following recommendation for ED management following RT in a recent review: Patients should initially be prescribed sildenafil to be used at a dose that gives them a penetration hardness erection twice a week. On the remaining five nights, they are advised to use sildenafil 25 mg when going to bed at night 10. The authors further emphasise the importance of communicating the benefit of low-dose PDE5-Is to patients 10.

Intracavernosal injections is the second line therapy recommended by Stember and Mulhall 10. ICI are usually more effective than PDE5-Is in men receiving ADT 10,35. The authors recommend ICI injections up to three times per week, while taking low-dose PDE5-I on the days that the patients do not inject 10. Patients are further instructed to avoid using ICI within 18 h of taking a PDE5-I because the combined effects may increase the likelihood of priapism.

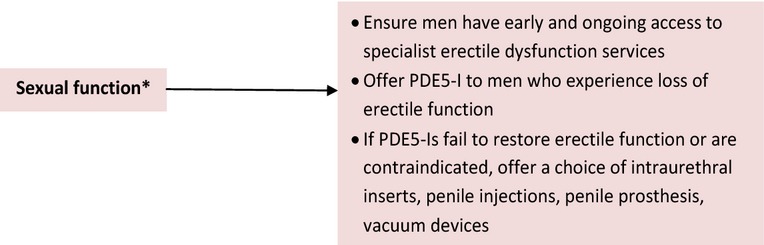

The NICE consultation guidelines on Prostate Cancer recommend offering PDE5-Is to men who experience loss of EF 72. Furthermore, NICE recommend that if PDE5-Is fail to restore EF, or are contraindicated, men should be offered a choice of intraurethral inserts, penile injections, penile prosthesis or vacuum devices (VED). However, NICE do not specify the order of ED management interventions nor do they specify strategies according to specific prostate cancer treatment modality and patient demographics (Figure6) 72.

Figure 6.

Prostate cancer NICE guidelines 72. *Sexual function term used by NICE though the treatments are solely for erectile dysfunction

Proposed management options to be considered by healthcare professionals are detailed in Table4. Some recommendations are evidence based, while others are based on consensus opinion generated within the expert panel survey. The recommendations in the algorithm should be considered independently of the patient's relationship status.

Table 4.

Summary recommendations for ED rehabilitation programme post-RT/BT/ADT

| Summary recommendations for ED rehabilitation programme |

|---|

| Pretreatment recommendations |

| Pretreatment discussion with the man and his partner of the impact of RT/BT/ ADT on sexual function, delayed ED development timelines and rationale for ED rehabilitation programme Ensure men and couples are sufficiently prepared for disruption to their sexual lives and expectations of EF recovery are realistically managed |

| The man and partner's current sexual function should be assessed as part of any ED management programme pre-and posttreatment. Partners may require medical/psychosexual therapy if they have concurrent sexual difficulties that may jeopardise rehabilitation efforts |

| Pretreatment assessment of a couple's readiness to engage in a ED rehabilitation programme is advisable |

| Pretreatment assessment of any comorbidities or concurrent medication that would affect sexual function |

| Assess patients’ contributory lifestyle factors (diet, BMI, alcohol/smoking and physical activity) |

| Check baseline testosterone level to exclude an existing testosterone deficiency |

| Posttreatment recommendations |

| Discuss the implementation of an ED rehabilitation programme with men and partners |

| ED management initiation time |

| Consider early initiation of PDE5-I (soon after start of RT/ADT) or within 3–6 months of treatment at least |

| ED management algorithm |

| See Figure5 for management algorithm recommendations for EF restoration after treatment with RT/ADT |

| Determine cause of ED – low sexual desire ± inability to get an erection? Are nocturnal/early morning erections occurring? |

| Consider conservative approaches: pelvic floor exercise and lifestyle changes |

| Consider first-line treatment with low-dose PDE5-I daily (with higher doses given, on demand × 1 per week minimum if required) Combination therapy may be needed for some patients (generally PDE5-I + VED) Psychosexual therapy, especially for patients on ADT with persistent low desire + individual/couple distress |

| Use the most effective PDE5-I at optimal dose level on at least eight occasions before switching drug/management strategy NB. sildenafil is now available in generic form |

| Add VED to PDE5-I monotherapy as a second line option |

| Add intraurethral alprostadil/ICI followed by implants if initial treatment strategies fail |

| Referral to appropriate psychological/psychosexual therapy services |

| Counselling to assist couples in adjusting to permanent changes in sexual function |

| Timetable sexual intercourse once a week to assist management of low desire |

| Re-assessment |

| Once ED management is initiated, re-assess at regular intervals posttreatment preferably every 3 months |

| ED management duration |

| Recommend trying one strategy on at least eight occasions (or approximately 3 months) before switching to another strategy unless the patient experiences adverse events warranting an early switch |

| Individualise duration of management for each man/couple as strict time limits are inappropriate in clinical practice Management duration can range from 3 months until the man no longer needs EF support |

Summary

Men undergoing RT/ADT for prostate cancer are at increased risk for ED.

In this article, we have proposed a comprehensive ED management algorithm to promote assisted or unassisted EF support for men experiencing ED associated with RT/ADT. Many men achieve assisted erections with PDE5-I use, while others benefit more from a combined ED management approach incorporating biomedical interventions, lifestyle/exercise programmes, psychosexual counselling and other erectile aids.

In addition to implementing this algorithm, understanding the rationale for proactive EF restoration strategies and the management of patient expectations is crucial for clinicians, men and partners in light of the delayed onset pattern of ED following RT/BT and the impact of ADT-induced loss of sexual motivation and desire on their sexual relationship.

Author contributions

All authors took part in the survey for clinicians, reviewed and edited the publication, which was produced by Isabel White and Mike Kirby with editorial assistance from Dr Sabah Al-Lawati at Right Angle.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the development of this clinical guidance was provided by Prostate Cancer UK, Macmillan Cancer Support and the British Uro-oncology Group (BUG). The authors acknowledge Right Angle Communications for editorial assistance.

References

- 1. Cancer research UK website http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/index.htm (accessed April 2014)

- 2.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: exploring the meanings of “erectile dysfunction”. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:649–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014. CG175 Prostate cancer http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG175/NICEGuidance/pdf/English (accessed May 2014)

- 4.British Uro-Oncology Group. 2013. Multi-disciplinary team (MDT) guidance for managing prostate cancer http://www.bug.uk.com/publications.php, September (accessed April 2014)

- 5.Sountoulides P, Rountos T. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: prevention and management. ISRN Urol. 2013;2013:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2013/240108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candy B, Jones L, Williams R, Tookman A, King M. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction secondary to treatments for prostate cancer: findings from a Cochrane systematic review. BJU Int. 2008;102(4):426–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miles CL, Candy B, Jones L, Williams R, Tookman A, King M. Interventions for sexual dysfunction following treatments for cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005540. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005540.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meuleman EJ, Mulders PF. Erectile function after radical prostatectomy: a review. Eur Urol. 2003;43:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittmann D, Montie JE, Hamstra DA, Sandler H, Wood DP., Jr Counseling patients about sexual health when considering post-prostatectomy radiation treatment. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21(5):275–84. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stember DS, Mulhall JP. The concept of erectile function preservation (penile rehabilitation) in the patient after brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2012;11(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulhall J, Ahmed A, Parker M, Mohideen N. The hemodynamics of erectile dysfunction following external beam radiation for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):432–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, et al. The importance of radiation doses to the penile bulb vs. crura in the development of postbrachytherapy erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;4:1055e1062. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iversen P, Tyrrell CJ, Kaisary AV, et al. Bicalutamide monotherapy compared with castration in patients with nonmetastatic locally advanced prostate cancer: 6.3 years of followup. J Urol. 2000;164:1579–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzola CR, Mulhall JP. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on sexual function. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(2):198–203. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2996–3010. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marumo K, Baba S, Murai M. Erectile function and nocturnal penile tumescence in patients with prostate cancer undergoing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist therapy. Int J Urol. 1999;6:19–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.1999.06128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tal R, Mueller A, Mulhall JP. The correlation between intracavernosal pressure and cavernosal blood oxygenation. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2722–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soloway CT, Soloway MS, Kim SS, Kava BR. Sexual, psychological and dyadic qualities of the prostate cancer ‘couple’. BJU Int. 2005;95:780–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:238–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossmann M, Zajac JD. Androgen deprivation therapy in men with prostate cancer: how should the side effects be monitored and treated? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;74(3):289–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braga-Basaria M, Dobs AS, Muller DC, et al. Metabolic syndrome in men with prostate cancer undergoing long-term androgen-deprivation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3979–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MR, Lee H, Nathan DM. Insulin sensitivity during combined androgen blockade for prostate cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1305–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galva˜o DA, Spry NA, Taaffe DR, et al. Changes in muscle, fat and bone mass after 36 weeks of maximal androgen blockade for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102:44–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galva˜o DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Joseph D, Turner D, Newton RU. Reduced muscle strength and functional performance in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen suppression: a comprehensive cross-sectional investigation. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:198–203. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roayaei M, Ghasemi S. Effect of androgen deprivation therapy on cardiovascular risk factors in prostate cancer. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(7):580–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiBlasio CJ, Hammett J, Malcolm JB, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors for the development of de novo psychiatric illness in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Can J Urol. 2008;15:4249–56. , discussion 4256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott J, Fallows A, Staetsky L, et al. The health and well-being of cancer survivors in the UK: findings from a population-based survey. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(Suppl. 1):S11–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potosky AL, Knopf K, Clegg LX, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes after primary androgen deprivation therapy: results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(17):3750–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.17.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potters L, Torre T, Fearn PA, Leibel SA, Kattan MW. Potency after permanent prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1235–42. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haliloglu A, Baltaci S, Yaman O. Penile length changes in men treated with androgen suppression plus radiation therapy for local or locally advanced prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007;177(1):128–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higano CS. Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3720–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.8509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiBlasio CJ, Malcolm JB, Derweesh IH, et al. Patterns of sexual and erectile dysfunction and response to treatment in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102(1):39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Budäus L, Bolla M, Bossi A, et al. Functional outcomes and complications following radiation therapy for prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol. 2012;61(1):112–27. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirby MG, White ID, Butcher J, et al. Development of UK recommendations on treatment for post-surgical erectile dysfunction. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(5):590–608. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – levels of evidence http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025 (accessed April 2014)

- 37.Zelefsky MJ, Shasha D, Branco RD, et al. Prophylactic sildenafil citrate for improvement of erectile function in men treated by radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.097. Mar 3 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ilic D, Hindson B, Duchesne G, Millar JL. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of nightly sildenafil citrate to preserve erectile function after radiation treatment for prostate cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2013;57(1):81–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L, Qian S, Liu L, et al. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors could be efficacious in the treatment of erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Int. 2013;90(3):339–47. doi: 10.1159/000343730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watkins-Bruner D, James JL, Bryan CJ, et al. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trial of treating erectile dysfunction with sildenafil after radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation therapy: results of RTOG 0215. J Sex Med. 2011;8(4):1228–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pahlajani G, Raina R, Jones JS, et al. Early intervention with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors after prostate brachytherapy improves subsequent erectile function. BJU Int. 2010;106(10):1524–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricardi U, Gontero P, Ciammella P, et al. Efficacy and safety of tadalafil 20 mg on demand vs. tadalafil 5 mg once-a-day in the treatment of post-radiotherapy erectile dysfunction in prostate cancer men: a randomized phase II trial. J Sex Med. 2010;7(8):2851–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teloken PE, Parker M, Mohideen N, Mulhall JP. Predictors of response to sildenafil citrate following radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2009;6(4):1135–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Incrocci L, Slob AK, Hop WC. Tadalafil (Cialis) and erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: an open-label extension of a blinded trial. Urology. 2007;70(6):1190–3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teloken PE, Ohebshalom M, Mohideen N, Mulhall JP. Analysis of the impact of androgen deprivation therapy on sildenafil citrate response following radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007;178(6):2521–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Incrocci L, Slagter C, Koos Slob A, Hop WCJ. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study to assess the efficacy of Tadalafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction following three-dimensional conformal external-beam radiotherapy for prostatic carcinoma. Int J Rad Oncol. 2006;66:439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schiff JD, Bar-Chama N, Cesaretti J, Stock R. Early use of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor after brachytherapy restores and preserves erectile function. BJU Int. 2006;98(6):1255–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohebshalom M, Parker M, Guhring P, Mulhall JP. The efficacy of sildenafil citrate following radiation therapy for prostate cancer: temporal considerations. J Urol. 2005;174(1):258–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000164286.47518.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Incrocci L, Hop WCJ, Slob KA. Efficacy of sildenafil in an open-label study as a continuation of a double-blind study in the treatment of erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(1):116–20. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Incrocci L, Koper PCM, Hop WCJ, Slob K. Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) and erectile dysfunction following external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Physiol. 2001;5(5):1190–5. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01767-9. 1( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forbat L, White I, Marshall-Lucette S, Kelly D. Discussing the sexual consequences of treatment in radiotherapy and urology consultations with couples affected by prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109(1):98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2689–700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cormie P, Newton RU, Taaffe DR, et al. Exercise maintains sexual activity in men undergoing androgen suppression for prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16(2):170–5. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, Schulz R. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):443–52. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartmann U, Burkart M. Erectile dysfunctions in patient-physician communication: optimized strategies for addressing sexual issues and the benefit of using a patient questionnaire. J Sex Med. 2007;4(1):38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tombal B. A holistic approach to androgen deprivation therapy: treating the cancer without hurting the patient. Urol Int. 2009;83:373–8. doi: 10.1159/000251174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson ME, Buyyounouski MK. Androgen deprivation therapy toxicity and management for men receiving radiation therapy. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:580306. doi: 10.1155/2012/580306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jannini EA, Screponi E, Carosa E, et al. Lack of sexual activity from erectile dysfunction is associated with a reversible reduction in serum testosterone. Int J Androl. 1999;22:385–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bourke L, Kirkbride P, Hooper R, Rosario AJ, Chico TJ, Rosario DJ. Endocrine therapy in prostate cancer: time for reappraisal of risks, benefits and cost-effectiveness? Br J Cancer. 2013;108(1):9–13. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahn HS, Park CM, Lee SW. The clinical relevance of sex hormone levels and sexual activity in the ageing male. BJU Int. 2002;89:526–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martinez-Jabaloyas JM, Queipo-Zaragoza A, Pastor-Hernandez F, Gil-Salom M, Chuan-Nuez P. Testosterone levels in men with erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2006;97:1278–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, et al. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):123–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nejat RJ, Rashid HH, Bagiella E, Katz AE, Benson MC. A prospective analysis of time to normalization of serum testosterone after withdrawal of androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol. 2000;164:1891–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gulley JL, Figg WD, Steinberg SM, et al. A prospective analysis of the time to normalization of serum androgens following 6 months of androgen deprivation therapy in patients on a randomized phase III clinical trial using limited hormonal therapy. J Urol. 2005;173:1567–71. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154780.72631.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bong GW, Clarke HS, Jr, Hancock WC, Keane TE. Serum testosterone recovery after cessation of long-term luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2008;71:1177–80. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilke DR, Parker C, Andonowski A, et al. Testosterone and erectile function recovery after radiotherapy and long-term androgen deprivation with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists. BJU Int. 2006;97(5):963–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Traish AM, Park K, Dhir V, Kim NN, Moreland RB, Goldstein I. Effects of castration and androgen replacement on erectile function in a rabbit model. Endocrinology. 1999;140(4):1861–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Isidori AM, Buvat J, Corona G, et al. A critical analysis of the role of testosterone in erectile function: from pathophysiology to treatment-a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;65(1):99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Welliver RC, Jr, Mechlin C, Goodwin B, Alukal JP, McCullough AR. A pilot study to determine penile oxygen saturation before and after vacuum therapy in patients with erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2014;11(4):1071–7. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahmadi H, Daneshmand S. Androgen deprivation therapy: evidence-based management of side effects. BJU Int. 2013;111(4):543–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hackett G, Kell P, Ralph D British Society for Sexual Medicine. British Society for Sexual Medicine guidelines on the management of erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1841–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CG58 Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management. [PubMed]