Abstract

Aims

To: (i) investigate the development of smoking and snus use among Norwegian adolescents, and (ii) describe the users in each group.

Design

Two population-based surveys with identical procedures in 2002 (response rate 91.0%) and 2010 (response rate 84.3%).

Setting

Norway.

Participants

A total of 6217 respondents, aged 16–17 years.

Measurements

Data were collected on smoking and snus use, socio-demographic factors, school adjustment, social network, sport activities, alcohol and cannabis use and depression symptoms.

Findings

Prevalence of daily smoking fell from 23.6% in 2002 to 6.8% in 2010 (P < 0.001), while the prevalence of daily snus use increased from 4.3 to 11.9% (P < 0.001). Dual daily use of cigarettes and snus remained at 1%. The relative proportion of non-daily smokers using snus increased steeply. Both snus users and smokers reported more adverse socio-economic backgrounds, less favourable school adjustment and higher levels of alcohol intoxication and cannabis use than non-users of tobacco. However, snus users were better adjusted to school and used cannabis less often than smokers.

Conclusions

Adolescent smoking prevalence has fallen dramatically in Norway, accompanied by a smaller increase in snus use. Young snus users in Norway have many of the same risk factors as smokers, but to a lesser degree.

Keywords: Alcohol, cannabis, population study, smoking, snus use, sports

Introduction

In tobacco policy the goal has been the elimination of tobacco use in all its forms 1. However, during the last few years, harm reduction-orientated strategies have been proposed 2. One reason is the evidence that some forms of tobacco, particularly smokeless types, are associated with less harm than cigarettes 3. There is also some evidence that use of smokeless tobacco by smokers (dual use) is often motivated by smoking reduction 4. However, these new harm reduction-orientated suggestions have met firm opposition 5.

Another, and potentially disturbing, aspect of the present situation is related to the fact that the use of snus (low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco, Swedish type) among young people has been increasing in countries such as Norway 6, Sweden 7 and in the United States 8. Does this mean that those who might have started to smoke now turn to less dangerous smokeless tobacco? Or are new groups of adolescents at risk? This question has motivated the study.

In Norway, traditional moist snuff was popular in the first part of the 20th century, followed by a period with low sales 4. The reintroduction of snus use around 1990 was based on a new, drier product, which comes in a variety of flavours, and is used in small sachets (similar to a tea-bag). An increasing proportion of users are female 6. At the same time, smoking has declined rapidly.

Low socio-economic status 9,10, conduct problems 11,12, depressive symptoms 13, other mental health problems 14 and low school achievement 15 have been linked to smoking and nicotine dependence. A number of studies have also investigated predictors of successful attempts to quit smoking. Previous quit attempts and level of dependence are consistent predictors. However, educational level does not seem to be related to quitting success 16. Nevertheless, smoking seems increasingly to have become part of a lower-class and stigmatized social status 17.

Fewer studies have investigated snus users. A Swedish study revealed that paternal use of snus increased the risk of snus use in offspring 18, while two other Swedish studies indicated that users of snus are also recruited from groups with low socio-economic status (SES) 19,20. Similarly, a US study found that snus use among young adults was more prevalent among those with less than high school education 8. Research from Norway provides more mixed results: while one study indicated that snus use was not linked to parental SES 21, another uncovered less snus use among adolescents who planned to take higher education 22. A third Norwegian study reported that young users of snus were characterized by a more middle-class orientated life-style than smokers 23.

Snus users report higher levels of alcohol intoxication than non-users of tobacco and, in this respect, they do not differ from smokers 24. When it comes to the use of illegal substances, conduct problems and mental health, little is known. However, a number of studies have investigated associations with sports. Studies from Finland indicate high levels of snus use among those active in team sports 25, Finnish Olympic athletes had increased rates of snus use 26 and, in the United States, elevated rates of snus use were found among organized college student athletes 27, as well as among professional baseball players 28. A recent Norwegian study among students at elite-sports high schools found that those who competed in team sports, such as handball and football, used snus more often than others 29. This may be one reason why snus use often is perceived as trendier than smoking 30.

In a recent Norwegian study of males aged 16–74 years, dual use of snus and cigarettes was low (1%) 4; however, US data indicate that dual use is most common among adolescents and young adults 31, and that this dual use pattern may be increasing 32. Thus, combinations of cigarette and snus use among adolescents should be monitored closely.

A methodological problem in recent studies of tobacco use is the reduction in response rates in surveys. Smoking habits predict attrition 33,34; thus, the decreasing prevalence rates of smoking may be a methodological artefact. In this study we use two population-based surveys conducted in 2002 and 2010, with identical procedures and high response rates. They allow us to compare prevalence rates over this 8-year span.

Research questions

We asked:

How have the patterns of smoking and snus use developed among 16–17-year-olds in the period 2002–10?

What characterizes smokers and users of snus, respectively, with regard to SES and family background, school adjustment, use of alcohol and cannabis, mental health, perceived social acceptance and sports and leisure activities?

Method

Participants and procedure

We used two population-based data sets, sampled in the compulsory Norwegian school system in 2002 and 2010, which has been described in more detail previously 35. Cluster-sampling was applied with schools as units. In 2002, students attending the first 2 years of senior high schools took part in the study, and all schools in the country were included in the register from which they were selected. They were drawn with a probability according to size (proportional allocation), securing representativeness. In 2010, the same schools were asked to participate. Two schools declined and they were replaced by back-up schools of similar geographic location and size. On average, 104.04 students (standard deviation = 58.53) participated in the study at each school in 2010, whereas 132.23 (standard deviation = 60.74) participated in 2002. The number of students per school varied from 30 to 247 in 2010 and from 27 to 226 in 2002.

All students gave informed consent in accordance with the standards prescribed by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate, and the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics endorsed the surveys. The response rates in 2002 and 2010 were 91.0 and 84.3%, respectively. The total sample of 6217 included 3173 boys (50.8%) and 3044 girls (48.5%). Most of the analyses in the present study relate to the 2010 data collection, when the sample consisted of 2796 students: 1449 boys (51.8%) and 1347 girls (48.2%).

Measures

Smoking and snus use

Smoking was assessed by the question ‘do you smoke?’, with response options ‘have never smoked’, ‘have never smoked regularly and do not smoke now’, ‘have smoked regularly, but have quit now’, ‘do smoke, but not daily’ and ‘smoke daily’. The first three response categories were combined into one, indicating that the participant did not currently smoke. Snus use was assessed in the same manner.

Parental characteristics

We asked about parental educational level, and whether or not participants were living with both biological parents. We also assessed whether mother or father was living on social welfare or was unemployed. As a measure of perceived poverty, we asked: ‘has your family been well off or short of money during the last two years?’. Response options were on a five-point scale from 1, ‘we were well off during this time’ to 5, ‘we were short of money during this time’. As a proxy of ‘cultural capital’ 36, we asked about the number of books at home, with the response options ranging from 1 ‘none’ to 7 ‘more than 1000 books’. To capture parental alcohol intoxication, we asked: ‘have you ever seen your parents drunk?’. Response options were on a five-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘a few times a week’.

School adjustment and educational plans

We asked about grades in Norwegian, mathematics and English, and mean scores were computed, ranging from 1 (lowest grade) to 6 (highest grade). We asked about the number of times the respondent had skipped school in the previous year; response options ranged on a five-point scale from ‘none’ to ‘more than 20 times’. Further, we asked about plans for future education, where ‘university or other lengthy education’ was contrasted with other options.

Substance use, conduct problems and depressive symptoms

Data were collected about the frequency of alcohol intoxication and cannabis use during the previous 12 months, using a six-point response scale that ranged from 1, ‘never’ to 6, ‘more than 50 times’. A 15-item measure of conduct problems over the previous 12 months, which approximated the diagnostic criteria for conduct disorders in the DSM-III-R, was employed 37. A cut-off at 3+ problems was set in some of the analyses. Depressive symptoms were measured by Kandel & Davies’ Depressive Mood Inventory (values 1–4) 38.

Network, sports, leisure-time activities

A revised version of the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents was used, with the five-item subscale ‘social acceptance’ 39. We asked how often during the last 14 days the respondent had been training ‘with a sports team’, ‘at a fitness centre’ or ‘alone’. We also asked about participation in ‘team sports’ (e.g. basketball, football and handball) and ‘individual sports’, and about unorganized leisure activities such as ‘hanging around at a street corner’.

Covariates

Age, gender and country of birth (Norway or abroad) were assessed.

Statistics

To examine gender differences in time trends of the prevalence of smoking and snus use, we conducted interaction analyses where time-point, gender and the product of time-point and gender were included as predictor variables in logistic regression analyses. Similarly, we conducted logistic regression interaction analyses to examine gender differences in the relationship between each predictor and tobacco use, controlling for age and country of birth and all other predictor variables. Differences between those who had not used tobacco, snus users and smokers were examined by means of χ2 tests for categorical variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Due to the extremely low prevalence of dual daily use of snus and cigarettes, it was not possible to compare these groups with other tobacco use statuses in multivariate analyses. To examine predictors of smoking and snus use, respectively, in multivariate analyses, multi-level multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted in which students (level 1) were nested within schools (level 2). Only student-level variables were included as predictors, as the main purpose of the present research was to identify predictors on the individual level and multi-level analyses were used to model non-independence of observations due to cluster sampling. The categories of the outcome variable were daily snus use, daily smoking and no use of tobacco. Each model produced two comparisons: the odds of smoking daily relative to not using tobacco and the odds of using snus daily compared to not using tobacco. We conducted additional analyses to compare smokers and snus users with each other. The full information maximum likelihood estimator was used to handle missing data 40 by means of Mplus version 7.0 41. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used for model selection. All predictor variables were included simultaneously, and variables were excluded if their exclusion resulted in better model fit.

Results

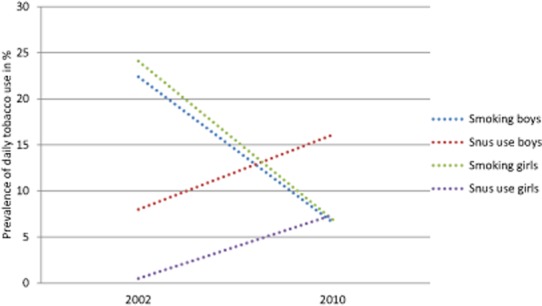

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of daily smoking and daily use of snus in 2002 and 2010 by gender. In the total sample, we observed a reduction in daily smoking from 23.6 to 6.8% (P < 0.001), and no gender differences in the change in smoking prevalence were detected (P = 0.723). In 2010, 6.6% of boys and 6.9% of girls were daily smokers (P = 0.769). During the same period, use of snus increased from 4.3 to 11.9% (P < 0.001). There was a proportionally larger increase in frequency of snus use among girls than boys (P < 0.001). In 2010, 16.1% of boys and 7.4% of girls used snus daily (P < 0.001). In total, there were 26.8% daily users of any form of tobacco in 2002, a figure that had fallen to 17.6% in 2010 (P < 0.001). The dual daily use of cigarettes and snus was very low in 2002 (0.8%) as well as in 2010 (1.0%).

Figure 1.

Daily smoking and daily snus use by 16–17-year-old students, in 2002 and 2010, by gender

In Table 1 some more subtle nuances are uncovered: here, we present the cross-tabulations between the three categories (i) non-smoking, (ii) non-daily smoking and (iii) daily smoking, and corresponding snus categories, in 2002 and 2010. Of the non-daily smokers, only 17.5% also used snus on a non-daily or daily basis in 2002, while this percentage had increased to 53.8% in 2010 (P < 0.001) by 2010. Thus, even though the prevalence of daily smoking had been rapidly decreasing and there were smaller, but significant reductions of the proportion of non-daily smokers (from 12.2 to 8.1%, P < 0.001), the relative proportion of non-daily smokers who were using snus on a non-daily or daily basis had tripled.

Table 1.

Associations between smoking and snus use in 2002 and 2010

| No snus use n (%) | Non-daily snus n (%) | Daily snus n (%) | Total n (%) | χ2 (d.f.), P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | |||||

| Non-smoking | 2087 (93.8) | 57 (2.6) | 82 (3.7) | 2226 (100) | 173.1 (4) <0.001 |

| Non-daily smoking | 340 (82.5) | 34 (8.3) | 38 (9.2) | 412 (100) | |

| Daily smoking | 662 (82.8) | 112 (14.0) | 26 (17.8) | 800 (100) | |

| 2010 | |||||

| Non-smoking | 2079 (86.6) | 116 (4.8) | 207 (8.6) | 2401 (100) | 415.6 (4) <0.001 |

| Non-daily smoking | 95 (43.2) | 28 (12.7) | 97 (44.1) | 220 (100) | |

| Daily smoking | 110 (81.2) | 52 (27.2) | 29 (15.2) | 191 (100) | |

We first conducted interaction analyses which showed that in 2010, girls and boys differed in how smoking was associated with parents receiving social welfare or not [P < 0.01; girls’ odds ratio (OR) = 0.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.26–1.23, P = 0.15; boys’ OR = 2.56, 95% CI = 1.35–4.85, P < 0.01]; no other gender differences were found in 2010. Therefore, we combined the data from girls and boys in all further analyses.

In Table 2, we describe those who were not using any tobacco product daily (NON), daily users of snus (SNU) and daily smokers (SMO). Possible differences between the groups were tested by χ2 tests and ANOVA, with the variables organized into four groups: (i) parental characteristics; (ii) school adjustment and (iii) substance use, conduct problems and mental health; and (iv) network, sports and leisure. The general picture uncovered was that the NON group reported the most favourable scores and SMO the least favourable. There were some exceptions: there were small differences between NON and SNU with regard to socio-economic background factors. The SNU group reported the highest level of perceived social acceptance. Finally, the SNU and SMO groups reported identical levels of alcohol intoxication scores, which were clearly higher than in the NON group.

Table 2.

Characteristics of those not using tobacco, snus users and smokers in 2010

| No daily tobacco use (NON) n = 2303 | Daily snus use (SNU) n = 304 | Daily smoking (SMO) n = 160 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental characteristics | ||||

| Not living with both parents, n (%) | 914 (39.7) | 142 (46.7) | 160 (63.1) | a*, b***, c*** |

| Parental education, index 1–4, mean (SD) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | b***, c*** |

| Father or mother on social welfare, n (%) | 313 (13.6) | 43 (14.1) | 44 (27.5) | b***, c*** |

| Family perceived as poor, n (%) | 139 (6.0) | 23 (7.6) | 24 (15.0) | b***, c* |

| Books at home, index 1–7, mean (SD) | 4.6 (1.3) | 4.3 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.5) | a***, b***, c*** |

| Parental alcohol intoxication, n (%) | 114 (5.0) | 29 (9.5) | 31 (19.4) | a*, b***, c** |

| School adjustment | ||||

| Total grade score 1–6, mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.9) | a***, b***, c*** |

| Truancy, 0–5, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.4) | a***, b***, c*** |

| Plans for university education, n (%) | 1347 (58.5) | 137 (45.1) | 42 (26.2) | a***, b***, c*** |

| Substance use, conduct problems and mental health | ||||

| Alcohol intoxication, 0–5, mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.9) | a***, b*** |

| Use of cannabis, n (%) | 90 (3.9) | 48 (15.8) | 55 (34.4) | a***, b***, c*** |

| Conduct problems, n (%) | 15 (0.7) | 14 (4.6) | 21 (11.1) | a***, b***, c** |

| Depressive symptoms, 1–4, mean (SD) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.8) | b***, c** |

| Perceived social acceptance, sport and leisure-time activities | ||||

| Social acceptance, 1–4, mean (SD) | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | a***, c*** |

| Training in a sports club, 0–14, mean (SD) | 1.1 (2.0) | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.2 (0.8) | b***, c*** |

| Unorganized leisure, 0–14, mean (SD) | 4.7 (3.5) | 6.6 (3.8) | 6.9 (4.2) | a***, b*** |

P < 0.001;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.05.

Difference between NON and SNU;

difference between NON and SMO;

difference between SNU and SMO. SD = standard deviation.

The NON group reported the highest level of training in a sports club, followed by the SNU, and then SMO groups. We also conducted a number of additional analyses (not reported) with regard to sports involvement (training alone, training in team sports, training in self-defence sports), but no differences between the NON and SNU groups were found.

In Table 3, a series of multinomial logistic regression analyses is reported. In the first series, we entered the variables in the same blocks as reported in Table 2, with control within each block. In the final analyses, all variables were entered simultaneously.

Table 3.

Multiple multinomial logistic regression predicting snus use and smoking

| Block by block |

All variablesd |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snus use (SNU) versus no tobacco use (NON) |

Smoking (SMO) versus no tobacco use (NON) |

Snus use (SNU) versus no tobacco use (NON) |

Smoking (SMO) versus no tobacco use (NON) |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Parental characteristics | ||||||||

| Not living with both parents | 1.32b | 0.95–1.83 | 2.36*** | 1.71–3.25 | 1.16 | 0.82–1.66 | 1.62** | 1.13–2.32 |

| Parental education | 1.02b | 0.89–1.17 | 0.73** | 0.60–0.89 | 1.04 | 0.88–1.24 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.04 |

| Father or mother on social welfare | 0.93 | 0.67–1.28 | 1.51 | 1.00–2.27 | – | – | – | – |

| Family perceived as poor | 1.15 | 0.76–1.75 | 1.40 | 0.88–2.21 | 1.15 | 0.69–1.92 | 1.26 | 0.76–2.09 |

| Books at home | 0.88**a | 0.81–0.96 | 0.75** | 0.63–0.89 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.81* | 0.67–0.98 |

| Parental alcohol intoxication | 1.77**a | 1.25–2.51 | 3.22*** | 2.10–4.94 | 0.96 | 0.60–1.54 | 1.27 | 0.63–2.56 |

| School adaption | ||||||||

| Total grade score | 0.76***c | 0.66–0.87 | 0.43*** | 0.35–0.53 | 0.76***c | 0.66–0.88 | 0.45*** | 0.36–0.56 |

| Truancy | 1.50***b | 1.32–1.70 | 1.85*** | 1.67–2.05 | 1.27*** | 1.14–1.41 | 1.44*** | 1.28–1.61 |

| Plans for university education | 0.80c | 0.60–1.07 | 0.37*** | 0.25–0.54 | 0.83c | 0.63–1.10 | 0.46*** | 0.32–0.64 |

| Substance use, conduct problems and mental health | ||||||||

| Alcohol intoxication | 2.65*** | 2.28–3.08 | 2.44*** | 1.81–3.29 | 2.16*** | 1.80–2.58 | 2.01*** | 1.45–2.77 |

| Use of cannabis | 2.16***c | 1.41–3.31 | 6.44*** | 4.04–10.25 | 2.03***c | 1.37–3.01 | 5.78*** | 3.70–9.03 |

| Conduct problems | 2.26 | 0.85–5.97 | 3.03* | 1.06–8.64 | 2.27 | 0.75–6.81 | 2.19 | 0.73–6.58 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.19 | 0.98–1.44 | 1.32* | 1.00–1.75 | 1.27* | 1.06–1.51 | 1.21 | 0.86–1.69 |

| Networks, sports and leisure-time activities | ||||||||

| Social acceptance | 1.96***b | 1.48–2.60 | 1.01 | 0.73–1.39 | 2.22*** | 1.72–2.86 | 1.69** | 1.20–2.38 |

| Sports participation | 0.90**b | 0.85–0.96 | 0.60*** | 0.47–0.77 | 0.93*b | 0.87–0.99 | 0.65*** | 0.51–0.81 |

| Unorganized leisure | 1.13*** | 1.09–1.17 | 1.17*** | 1.10–1.24 | 1.08*** | 1.05–1.11 | 1.08** | 1.03–1.13 |

| Covariatese | ||||||||

| Age | – | – | – | – | 1.27 | 0.93–1.73 | 1.22 | 0.94–1.58 |

| Gender | – | – | – | – | 0.46***c | 0.32–0.67 | 1.41 | 0.92–1.91 |

| Country of birth | – | – | – | – | 0.59 | 0.34–1.04 | 1.02 | 0.54–1.74 |

All analyses controlled for gender, age and country of birth. OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of odds ratio.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Difference between snus and smoking, P < 0.05.

Difference between snus and smoking, P < 0.01.

Difference between snus and smoking, P < 0.001.

Father or mother on social welfare was not included in the because final model fit improved from Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 2086.77–2084.40 when excluding this variable.

OR for covariates are not reported for the first models because they vary for each of the four analyses conducted.

In the first blockwise series, we note that socio-economic and parental background factors played a more important role for the SMO group than the SNU group, and this difference was statistically significant with regard to parental educational level and parental alcohol intoxication. The next block reveals that SNU and SMO groups had reduced school adjustment, particularly the SMO group. The third block shows that the SNU and SMO groups had higher levels of substance use than the NON group, that the SMO group had higher levels of cannabis use than the SNU group and higher scores on conduct problems and symptoms of depression than the NON group. The last block shows that SNU and SMO groups had reduced levels of sports participation and higher levels of unorganized leisure, and the SNU group reported the highest levels of social acceptance. In all four models all predictor variables were kept in the model, as the AIC indicated no improvement of the models when excluding variables. Finally, all variables were entered simultaneously. Excluding parents receiving social welfare benefits increased the fit of the final model, whereas no other predictor reduced model fit. The final results show that parental variables lost significance, except for in the NON and SMO comparison, where SMO had experienced family break-up more often and came from homes with few books more often. Compared with the NON group, the SNU group had lower school grades, increased truancy, higher alcohol intoxication, more cannabis use, less sports participation and more unorganized leisure activities. The SMO group shows similar results, and compared with the NON group they less often had plans for university education. Both SNU and SMO groups had higher levels of self-perceived social acceptance than the NON group. Finally, we made a SNU/SMO comparison (not reported in Table 3). The SNU group had higher school grades, more often plans for university education, less frequent cannabis use and greater sports participation.

Discussion

The present study revealed a dramatic reduction in daily smokers; by 2010 the proportion had dropped to less than a third of the 2002 rate. Non-daily smoking also decreased. At the same time, snus use more than doubled. Smokers and snus users were characterized by more typical risk factors for substance use than non-users of tobacco in areas such as school grades, truancy, alcohol intoxication, cannabis use and unorganized leisure. When comparing smokers and snus users, some differences were also revealed: the snus users were better adjusted at school, they used cannabis less often and they were more often involved in sports.

Does it seem likely that adolescents who previously would have started to smoke now turn to snus? Based on our data, the answer is a conditional ‘yes’: the snus users exhibit a number of the same risk factors as smokers. Some of them may have chosen snus instead of cigarettes. Note that the finding stands in some contrast with the typical image of snus use in Norway, where snus users are depicted as trendier and more resourceful than smokers 30.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study has several strengths: the sample was population-based, we used well-validated measures and obtained high response rates in both data collections, although the rate dropped from 91.0% in 2002 to 84.3% in 2010. Studies show that tobacco use predicts non-response to some degree in epidemiological studies 42. The prevalence of smoking and snus use in 2010 may therefore have been somewhat underestimated. Note also that there is some dropout from the school system, and dropouts probably have higher prevalence of smokers than do others. Moreover, we used a sample of adolescents, and findings may not be generalizable to older age groups. Finally, because of the cross-sectional character of the data, we were not able to identify possible causal factors in the aetiology of smoking and snus use.

Smoking and snus in the context of polysubstance use

During the last couple of decades, a range of psychoactive substances has been used for recreational purposes, in a pattern described as ‘pick “n” mix’ 43. Studies now also highlight the importance of tobacco in this picture 44, and our findings reflect this trend: daily smoking is decreasing, but snus use and the combination of non-daily smoking and snus use are increasing. Moreover, both daily smokers and snus users reported similar and high levels of alcohol intoxication. Previous studies of polysubstance use among adolescents indicate that those who use only the legal substances of tobacco and alcohol are typically less involved in severe and problem-prone substance-using sequences than those who are involved with cannabis and other illegal substances 45. Our findings suggest that snus may occupy an even less severe position than cigarettes; the link between snus use and cannabis was weaker than that between smoking and cannabis.

Although daily smoking has decreased from 42 to 16% in Norway during the last 40 years, the proportion of non-daily smokers has remained stable at around 10% 6. Although smoking is increasingly stigmatized, to some degree cigarettes remain characterized by a contradiction between a symbol of style and freedom and more recent discourses of stigma 46. Non-daily smoking, in particular, is still associated with the former group of characteristics 47. The stable pattern of non-daily smoking, the increasing rate of snus use, even among females, and the combination of non-daily smoking and snus use may contribute to a more complex picture than that which is often portrayed. In the years to come one may perhaps witness a mix of low–frequent cigarette use more often, combined with snus use, opening for appealing identity formations, in the landscape of polysubstance use 48.

The new snus users

Snus users reported the highest level of self-perceived social acceptance in our study. In an early landmark study, Shedler & Block 49 found that ‘some sort of drug experimentation’ was associated with higher levels of integration and social adjustment than ‘no drug experimentation’ (p. 612). Other studies have reported similar findings; for example, alcohol abstainers have been characterized by greater loneliness and weaker social networks than moderate users of alcohol 50. Our findings add to this picture: even if snus users report a number of traditional risk factors, snus use also seems to occur among those who are socially integrated and have high levels of self-esteem. Conversely, well-established findings regarding snus use and participation in sports 26–28 were not confirmed. The snus users in our study were not more involved in sports than those who did not use tobacco. The participants in our study were younger than in most other studies, which may partially explain this. However, a previous Norwegian study sampled from elite-sports high schools also indicated increased snus use among athlete groups 29. One may hypothesize that in certain sports clubs or schools, snus use may function as an identity marker, and we may not have identified such groups through our population-based sampling strategy.

Snus in a harm reduction perspective

A number of reviews have indicated that snus is less dangerous than smoking 51,52. A new review investigated consequences of switching from cigarettes to snus by comparing current users who formerly smoked (‘switchers’) with those who continued to smoke (‘continuers’), and never users of snus who quit smoking (‘quitters’). Switchers and quitters were found to have identical risks for cancer and cardiovascular disease and clearly lower than for continuers 53. Thus, Norwegian adolescents’ switch from cigarettes to snus must, in a population health perspective, be considered an important step forward. At the same time, our findings indicate that the groups at risk for smoking and snus initiation are, to some degree, overlapping. Thus, there may be a potential for snus use as a harm reduction measure in this age group.

However, a disturbing aspect of the picture is the high prevalence of alcohol intoxication among snus users and the tendency to combine non-daily smoking and snus use. We do not know whether or not this may lead to regular smoking and to use of other psychoactive substances. Thus, we suggest that future studies should carefully monitor patterns of polysubstance use among adolescents, and that they should also include data on smoking and snus use.

Declaration of interests

None.

References

- 1.Gray N, Daube M. Guidelines for Smoking Control. Geneva: International Union Against Cancer; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borland R. Minimising the harm from nicotine use: finding the right regulatory framework. Tob Control. 2013;22:i6–9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine JA, Pollack H, Comfort ME. Academic and behavioral outcomes among the children of young mothers. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63:355–369. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lund KE, McNeill A. Patterns of dual use of snus and cigarettes in a mature snus market. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:678–684. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young D, Borland R, Coghill K. Changing the tobacco use management system: blending systems thinking with Actor-Network Theory. Rev Policy Res. 2012;29:251–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistisk sentralbyrå (SSB: Statistics Norway) Smoking Habits. Oslo: Statistics Norway; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norberg M, Lundqvist G, Nilsson M, Gilljam H, Weinehall L. Changing patterns of tobacco use in a middle-aged population—the role of snus, gender, age, and education. Glob Health Action. 2011;4 doi: 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5613. doi: 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharyya N. Trends in the use of smokeless tobacco in United States, 2000–2010. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2175–2178. doi: 10.1002/lary.23448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergusson D, Horwood J, Boden J. Childhood social disadvantage and smoking in adulthood: results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2007;102:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen W, Lavik NJ. Role modelling and cigarette smoking: vulnerable working class girls? A longitudinal study. Scand J Public Health. 1991;19:110–115. doi: 10.1177/140349489101900206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopfer C, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, Min SJ, McQueen M, Crowley T, et al. Conduct disorder and initiation of substance use: a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niemela S, Sourander A, Pilowsky DJ, Susser E, Helenius H, Piha J, et al. Childhood antecedents of being a cigarette smoker in early adulthood. The Finnish ‘From a Boy to a Man’ Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:343–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen W, von Soest T. Smoking, nicotine dependence and mental health among young adults: a 13-year population-based longitudinal study. Addiction. 2009;104:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence D, Mirou F, Zubrick R. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennanen M, Vartiainen E, Haukkala A. The role of family factors and school achievement in the progression of adolescents to regular smoking. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:57–68. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit E, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham H. Smoking, stigma and social class. J Soc Policy. 2012;41:83–99. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosendahl K, Galanti M, Giljam H. Smoking mothers and snuffing fathers: behavioural influences on youth tobacco use in a Swedish cohort. Tob Control. 2003;12:74–78. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engstrøm K, Magnusson C, Galanti M. Socio-demographic, lifestyle and health characteristics among snus users and dual tobacco users in Stockholm County, Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:619. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagquist C. Health inequalities among adolescents—the impact of academic orientation and parents’ education. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:21–26. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Øverland S, Tjora T, Hetland J, Aarø LE. Associations between adolescent socioeducational status and use of snus and smoking. Tob Control. 2010;19:291–296. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grotvedt L, Stigum H, Hovengen R. Social differences in smoking and snuff use among Norwegian adolescents: a population based survey. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sæbø G. Cigarettes, snus and status. About life-style differences between users of various tobacco products. Norsk Sosiologisk Tidsskrift [Norwegian J Sociol] 2013;21:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen E, Rise J, Lund KE. Risk and protective factors of adolescent exclusive snus users compared to non-users of tobacco, exclusive smokers and dual users of snus and cigarettes. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2288–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattila VM, Raisamo S, Pihlajamäki H, Mäntysaari M, Rimpelä A. Sports activity and the use of cigarettes and snus among young males in Finland 1999–2010. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Patja K, Palmu P, Prattala R, Martelin T, et al. Snuff use and smoking in Finnish Olympic athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:581–586. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green GA, Uryasz F, Petr TA, Bray CD. NCAA study of substance use and abuse habits of college student-athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:51–56. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Severson H, Kelein K, Leichtenstein E, Kaufman N, Orleans C. Smokeless tobacco use among professional baseball players: survey results, 1998 to 2003. Tob Control. 2005;14:31–36. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinsen M, Sundgot-Borgen J. Adolescent elite athletes’ cigarette smoking, use of snus, and alcohol. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01505.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiium N, Aarø LE, Hetland J. Subjective attractiveness and perceived trendiness in smoking and snus use: a study among young Norwegians. Health Educ Res. 2008;24:162–172. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomar SL, Alpert HR, Nonolly GN. Patterns of dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among US males: findings from longitudinal studies. Tob Control. 2010;19:104–109. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maher JE, Bushore CJ, Rohde K, Dent CW, Peterson E. Is smokeless tobacco use becoming more common among US male smokers? Trends in Alaska. Addict Behav. 2012;37:862–865. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson TP, Hubbell A, Wislar JS. Tobacco-reporting validity in an epidemiological drug-use survey. Addict Behav. 2005;30:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoeni RF, Stafford F, McGonagle A, Andreski P. Response rates in national panels surveys. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2013;645:60–87. doi: 10.1177/0002716212456363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Soest T, Wichstrøm L. Secular trends in depressive symptoms among Norwegian adolescents from 1992 to 2010. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:403–415. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9785-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourdieu P. Three stages of cultural capital. Actes Rech Sci Soc. 1979;30:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wichstrøm L, Skogen K, Øia T. The increased rate of conduct problems in urban areas: what is the mechanism? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:471–479. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kandel D, Davies M. Epidemiology of depressed mood in adolescents: an empirical study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1205–1212. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100065011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wichstrøm L. Harter's self-perception profile for adolescents—reliability, validity and evaluation of the question format. J Pers Assess. 1995;65:100–116. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6501_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 7th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCoy TP, Blocker JN, Champion H, Rhodes SD, Wagoner KG, Mitra A, et al. Attrition bias in a US internet survey of alcohol use among college freshmen. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:606–614. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker H, Measham F. Pick ‘n’ mix: changing patterns of illicit use. Drugs (Abingdon, UK) 1994;1:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malmberg M, Overbeek G, Monshouwer K, Lammers J, Vollebergh WAM, Engels R. Substance use risk profiles and associations with early substance use in adolescence. J Behav Med. 2010;33:474–485. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9278-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Derringer J, Krueger RF, Iacono WG, McGue M. Modeling the impact of age and sex on a dimension of poly-substance use in adolescence: a longitudinal study from 11- to 17-years-old. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheffels J. Stigma, or sort of cool. Young adults’ accounts of smoking and identity. Eur J Cult Stud. 2009;12:469–486. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krange O, Pedersen W. The return of the Marlboro man. Recreational smoking in young adults. J Youth Stud. 2001;4:155–177. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levinson AH, Campo S, Gascoine J, Jolly O, Zakharyan A, Tran ZV. Smoking, but not smokers: identity among college students who smoke cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:845–852. doi: 10.1080/14622200701484987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shedler J, Block J. Adolescent drug use and psychological health. Am Psychol. 1990;45:612–630. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leifman H, Kühlhorn E, Allebeck P, Andreasson S, Romelsjö A. Abstinence in late adolescence—antecedents to and covariates of a sober lifestyle and its consequences. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:113–121. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bates C, Fagerstrøm K, Jarvis MJ, Kunze M, McNeill A, Ramstrøm L. European Union policy on smokeless tobacco: a statement in favor of evidence based regulation for public health. Tob Control. 2003;12:360–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levy DT, Mumford EA, Cummings KM. The relative risks of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product compared with smoking cigarettes: estimates of a panel of experts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2035–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee PN. The effect on health of switching from cigarettes to snus—a review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;66:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]