Abstract

The koji mold Aspergillus kawachii is used for making the Japanese distilled spirit shochu. During shochu production, A. kawachii is grown in solid-state culture (koji) on steamed grains, such as rice or barley, to convert the grain starch to glucose and produce citric acid. During this process, the cultivation temperature of A. kawachii is gradually increased to 40°C and is then lowered to 30°C. This temperature modulation is important for stimulating amylase activity and the accumulation of citric acid. However, the effects of temperature on A. kawachii at the gene expression level have not been elucidated. In this study, we investigated the effect of solid-state cultivation temperature on gene expression for A. kawachii grown on barley. The results of DNA microarray and gene ontology analyses showed that the expression of genes involved in the glycerol, trehalose, and pentose phosphate metabolic pathways, which function downstream of glycolysis, was downregulated by shifting the cultivation temperature from 40 to 30°C. In addition, significantly reduced expression of genes related to heat shock responses and increased expression of genes related with amino acid transport were also observed. These results suggest that solid-state cultivation at 40°C is stressful for A. kawachii and that heat adaptation leads to reduced citric acid accumulation through activation of pathways branching from glycolysis. The gene expression profile of A. kawachii elucidated in this study is expected to contribute to the understanding of gene regulation during koji production and optimization of the industrially desirable characteristics of A. kawachii.

INTRODUCTION

Koji molds, such as the yellow koji mold Aspergillus oryzae, are important microbes for the production of many traditional Japanese fermented foods, such as sake, miso, and shoyu (1). The white koji mold Aspergillus kawachii, which was derived from the black koji mold Aspergillus luchuensis, is used in the production of shochu, a traditional Japanese distilled spirit (2–4). A. kawachii produces large amounts of citric acid in addition to several glycoside hydrolases, such as α-amylase and glucoamylase, which are also produced by A. oryzae. Glycoside hydrolases play an important role in shochu production as they degrade the complex polysaccharides found in rice and barley into smaller mono- or disaccharides that can be further utilized by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for ethanol fermentation. The citric acid-producing character of A. kawachii is also beneficial for shochu production as citric acid lowers the pH of the fermentation and thereby helps prevent microbial contamination, which is particularly problematic because shochu is mainly produced in Japan's southwest island of Kyushu, where the climate is relatively warm. Citric acid production by A. kawachii is a unique feature because it is not found in other koji molds, including A. oryzae.

A. kawachii has similar genomic and physiological features as Aspergillus niger, which is industrially used for the production of protein and citric acid. However, A. kawachii is clearly distinct from most A. niger strains with respect to the production of mycotoxins (5–7). Although several A. niger strains produce the mycotoxins fumonisin and ochratoxin, A. kawachii does not produce these mycotoxins. For this reason, A. kawachii is considered to be a safe microorganism for industrial use.

For the production of koji used for making shochu, the cultivation temperature of A. kawachii is strictly controlled. Typically, the temperature is raised to 40°C in the early cultivation stages to increase amylase activity and lowered to 30°C in the later stages to promote the production of citric acid (8). The cultivation conditions for A. kawachii were developed and refined based on the experiences of shochu brewers for controlling the production of optimal amounts of amylases and citric acid (9). However, the specific genes involved in these processes that are activated and/or repressed under the different temperature conditions remain unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the temperature-mediated changes that occur in A. kawachii at the gene expression level during the production of shochu koji. For this purpose, the transcriptomic profiling of A. kawachii using DNA microarrays was performed and compared under two different cultivation conditions: normal conditions, in which the temperature was raised to 40°C and then lowered to 30°C, and high-temperature conditions, in which the cultivation temperature was raised from 36 to 40°C and then maintained at 40°C. In particular, we focused on the effects of temperature reduction on the gene expression profiles of A. kawachii during solid-state culture to determine the significance of temperature control on koji production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

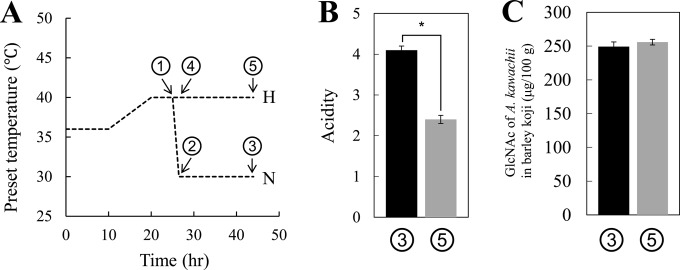

Strain and koji production.

The white koji mold A. kawachii SH46, which was recently renamed A. luchuensis SH46 (4), was obtained from Higuchi Matsunosuke Shoten Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), and used for koji production with barley polished to 70%. The barley was steamed (water adsorption rate, 35%) before being used for koji production, as described previously (9). The solid-state cultivation of A. kawachii on the barley was performed under normal (N)-temperature conditions, in which the temperature was increased from 36 to 40°C over a 25-h period and was then lowered to 30°C, and under high (H)-temperature conditions, in which the temperature was increased from 36 to 40°C over a 25-h period and then maintained at 40°C for 19 h (Fig. 1A). Barley koji (100 g) was prepared in triplicate under both N and H conditions and was used for the following experiments.

FIG 1.

Experimental conditions and properties of the barley koji produced in this study. (A) Cultivation temperature conditions. (B) Acidity of barley koji at the indicated sampling points (1 to 5) shown in panel A. (C) GlcNAc levels in barley koji at the sampling points indicated in panel A. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations. *, P value < 0.01 (Welch's t test).

Acidity and GlcNAc measurements of barley koji.

Acidity was measured to examine and compare citric acid production under the N and H culture conditions. For the analysis, 40 g of prepared koji was homogenized with 200 ml of water, and acidity was then measured by acid-base titration. GlcNAc levels in koji were also measured to evaluate the growth of A. kawachii on barley according to a previously described method with a slight modification (10). Briefly, approximately 7 g of barley koji was dried in an oven at 105°C for 1 h and then crushed to a powder. The crushed koji (500 mg) was washed three times with 20 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the resultant suspension was centrifuged at 1,580 × g for 10 min. The obtained pellet was mixed with 10 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 5 mg/ml yatalase (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan) and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. After further centrifugation at 1,580 × g for 10 min, the amount of GlcNAc in the supernatant was determined colorimetrically as previously described (11).

Quantification of metabolites.

Barley koji was collected at various time points between 25 and 45 h of cultivation, as indicated in Fig. 1A (sampling points 1, 2, 3, and 5) and frozen immediately at −80°C. Metabolome analysis of the collected samples was performed by Human Metabolome Technologies, Inc. (Tsuruoka, Japan), as follows. Samples of koji (50 mg) were crushed using a hammer, dissolved in 500 μl of methanol, and then disrupted by bead beating at 1,500 rpm for 2 min using a Shake Master NEO MBS-M10N21 (Biomedical Science, Tokyo, Japan). After the bead beating was repeated five times, the sample was further homogenized by shaking at 4,000 rpm for 1 min using a Micro Smash MS-100R (Tomy Digital Biology, Tokyo, Japan) and was then mixed with 500 μl of chloroform and 200 μl of Milli-Q water. After centrifugation of the sample at 2,300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, 400 μl of the water phase was transferred to an ultrafiltration module (Ultrafree MC PLHCC HMT, 5 kDa; Millipore) and centrifuged at 9,100 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The obtained filtrate was dried and redissolved in 50 μl of Milli-Q water. Metabolites were analyzed using a capillary electrophoresis–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOF/MS) system (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a fused silica capillary (50 μm [inside diameter] by 80 cm). The data were analyzed using MasterHands software (version 2.13.0.8.h). Statistical differences were calculated from triplicate data of independently produced barley koji by using Welch’s t test.

Preparation of RNA.

Barley koji was collected at various time points between 25 and 45 h of cultivation, as indicated in Fig. 1A (sampling points 2, 3, 4, and 5). The frozen barley koji samples were physically disrupted with a hammer in liquid nitrogen to keep the samples frozen. Two grams of the crushed koji was incubated with 5 ml of RNAiso reagent (TaKaRa Bio) at 50°C for 10 min with vigorous vortexing every 2 min. The sample was then incubated at room temperature for 5 min before being frozen at −80°C for over 1 h. The samples were thawed at room temperature and then centrifuged at 1,580 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The upper phase was retrieved, and 0.2 volumes of chloroform was added and vigorously mixed with the remaining sample, which was then further centrifuged at 1,580 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The upper phase was retrieved and purified using an SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of the RNA sample used for DNA microarray analysis was confirmed by electrophoresis with a BioAnalyzer instrument (Agilent Technologies).

DNA microarray analysis.

Probes for DNA microarray analysis were designed using a SurePrint G3 8 × 60K eArray (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) for the 11,488 predicted coding sequences (CDSs) of A. kawachii IFO 4308 (12). Five different probes were designed for each CDS. Cyanine-3 (Cy3)-labeled cRNA was prepared from 50 ng of RNA using a one-color microarray-based gene expression analysis low-input Quick Amp labeling kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by RNeasy column purification (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The microarray was hybridized with Cy3-labeled cRNA at 65°C for 17 h in a humid chamber and was then washed, dried, and scanned using an Image analyzer (Agilent Technologies). All microarray experiments were performed three times with RNA samples obtained from independently prepared barley koji. The triplicate data of five probes were analyzed by Tukey's bi-weight method, and the signal intensities were normalized by a quantile normalization method using the R package normalize.quantiles function (http://cran.r-project.org/index.html) (13). The expression ratio was calculated as log (base 2) ratio. If the q value was found to be less than 0.01 using the Limma package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) and the log2 fold change was less than −0.5 or greater than 0.5, it was considered to be a significant change (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). The differential gene expression identified in the DNA microarray analysis was confirmed by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), as described in the following section. The gene expression data were analyzed with manually constructed metabolic pathways of A. kawachii mainly based on models in A. niger (14, 15) (see Fig. S1). In addition, the genes were subjected to gene ontology (GO) analysis (see Data Set S2). The GO annotation of A. kawachii genes was based on InterProScan, and the analysis was performed using a Perl script (16, 17).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis.

For the validation of microarray-based expression data, real-time RT-PCR was performed. cDNAs were synthesized using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (perfect real time) (TaKaRa Bio) according to the manufacturer's protocol using 240 ng of total RNA as the template. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using a thermal cycler Dice real-time system MRQ (TaKaRa Bio) with SYBR premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus) (TaKaRa Bio). Specific primer sets for the 27 genes listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material were used for the amplification reactions. Genomic DNA of A. kawachii IFO 4308 (4.5 × 104, 9 × 104, 1.8 × 105, and 4.5 × 105 copies) was used as standard DNA. The actin gene was used to normalize mRNA expression levels, and the relative transcriptional levels of the 26 target genes were calculated (Table 1; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Genes up- and downregulated in response to lowering the koji cultivation temperature

| Reaction no. in Fig. 2 | Locus tag | Putative functionh | Fold change in expression byg: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray |

Real-time RT-PCR |

|||||

| N 26.5 h/H 26.5 h | N 44 h/H 44 h | N 26.5 h/H 26.5 h | N 44 h/H 44 h | |||

| 1 | AKAW_05831 | Glucokinase | 0.43b | 1.1 | 0.44d | 0.8 |

| 2 | AKAW_01051 | Fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase | 0.54b | 1.7c | 0.67e | 1.1 |

| 3 | AKAW_03207 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 0.62b | 1.3 | 0.73e | 0.93 |

| 4 | AKAW_07001 | Fructose bisphosphate aldolase | 0.60b | 1.2 | 0.69f | 1.2 |

| 5 | AKAW_02920 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.61b | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| 6 | AKAW_03245 | Phosphoglycerate mutase | 2.2a | 2.2 | 1.3e | 1.3 |

| 7 | AKAW_00804 | Pyruvate carboxylase (cytosol) | 1.7b | 1.6 | 1.8e | 1.2 |

| 8 | AKAW_01578 | 6-Phosphogluconolactonase | 0.57b | 1.3 | 0.61e | 0.89 |

| 9 | AKAW_01810 | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (decarboxylating) | 0.15b | 0.18c | 0.16f | 0.16f |

| 10 | AKAW_02256 | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (A) | 0.59a | 1.3 | 0.65e | 0.91 |

| 10 | AKAW_00489 | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (B) | 0.39b | 2.1c | 0.54e | 1.3 |

| 11 | AKAW_04326 | Transaldolase (sedoheptulose-7-phosphate:d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate glyceronetransferase) | 0.60b | 1.5 | 0.70e | 1.1 |

| 12 | AKAW_00232 | Transketolase (Sedoheptulose-7-phosphate:d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate glycolaldehydetransferase) | 0.18b | 0.26c | 0.26f | 0.24f |

| 13 | AKAW_03596 | α,α-Trehalosephosphate synthase (UDP forming) | 0.20b | 0.7 | 0.32e | 0.66f |

| 13 | AKAW_03597 | α,α-Trehalosephosphate synthase (UDP forming) | 0.22b | 0.9 | 0.25f | 0.70f |

| 13 | AKAW_05189 | α,α-Trehalosephosphate synthase (UDP forming) | 0.24b | 0.37 | 0.31e | 0.34 |

| 14 | AKAW_03775 | Trehalose phosphatase | 0.67b | 1.9 | 0.76f | 1.1 |

| 15 | AKAW_00120 | α,α-Trehalase | 0.51b | 1.1 | 0.63f | 0.68f |

| 16 | AKAW_10295 | Glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD dependent) | 0.097b | 0.18c | 0.14f | 0.15f |

| 17 | AKAW_05699 | Glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (FAD dependent) (FAD-dependent sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) | 0.56a | 0.78 | 0.74f | 0.57e |

| 18 | AKAW_01027 | Glycerol kinase | 0.54b | 0.95 | 0.70f | 0.79 |

| 19 | AKAW_09531 | Glycerone kinase | 0.45b | 1.1 | 0.63f | 0.73 |

| 20 | AKAW_01925 | PDH (acetyl-transferring) (PDH component E1-α) | 0.26b | 0.20c | 0.21e | 0.17f |

| 21 | AKAW_08633 | Pyruvate carboxylase (mitochondrial) | 0.64b | 1 | 0.4e | 0.34 |

| 22 | AKAW_08158 | Fumarate hydratase (S)-malate hydrolyase (fumarate forming) | 0.59b | 1.2 | 0.69f | 0.74 |

| 23 | AKAW_08716 | Malate synthase | 2.8b | 2.4 | 2.5d | 1.4 |

q value of <0.001.

q value of <0.01.

q value of <0.05.

P value of <0.001.

P value of <0.01.

P value of <0.05.

Ratios were determined for the indicated conditions and time points, identified such that N 26.5 h, for example, indicates the value for the N condition at 26.5 h.

FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase.

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE58454.

RESULTS

Genome comparison.

The results of the genome analysis of A. kawachii IFO 4308 performed in this study have been briefly summarized in the genome announcements in Eukaryotic Cell (12). Here, differences in the genome structures of A. kawachii, A. niger, and A. oryzae were compared to understand the characteristic productivities of organic acids and examine the degree of CDS conservation among these three Aspergillus species (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The number of predicted CDSs in the genomes of A. kawachii IFO 4308, A. niger CBS 513.88, and A. oryzae RIB40 were 11,488, 14,056, and 11,902, respectively (12, 18–20) (Aspergillus Genome Database [http://www.aspergillusgenome.org/]). A total of 3,797 CDSs were conserved at a 70% level of identity among these three Aspergillus species. The clustering analysis also identified that 4,852 CDSs were common only between A. kawachii IFO 4308 and A. niger CBS 513.88 and that 309 CDSs were common only between A. kawachii IFO 4308 and A. oryzae RIB40. As cultures of A. kawachii and A. niger accumulate markedly higher levels of citric acid than those of A. oryzae, the presence of genes involved in the metabolic tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle were compared. Four genes in the A. kawachii genome, encoding malate dehydrogenase (AKAW_04056), pyruvate carboxylase (AKAW_08633), and two citrate synthases (AKAW_00170 and AKAW_09689), were included in the cluster of genes that were common between A. kawachii and A. niger.

An important trait of koji molds used in the fermentation industry is the nonproduction of mycotoxins. Although several A. niger strains are known to produce ochratoxin (5, 7), A. kawachii IFO 4308 does not produce ochratoxin due to the deletion of a polyketide synthase gene involved in ochratoxin biogenesis (3). Previous genome analysis of A. kawachii IFO 4308 revealed that an approximately 21-kb genomic region that includes the polyketide synthase gene is deleted in this strain (12). A. kawachii also does not produce fumonisin (7), which is consistent with the finding that A. kawachii IFO 4308 lacks orthologs of nearly all fum genes involved in fumonisin biogenesis in A. niger (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) (19, 21).

Properties of barley koji.

Acid production by A. kawachii IFO 4308 in solid-state culture for barley koji production was measured for evaluating the accumulation of citric acid under two different culture conditions (Fig. 1A). The acidity of koji prepared under the normal (N) temperature condition was significantly higher than that of koji produced under sustained high-temperature conditions (Fig. 1B).

The growth of A. kawachii at each temperature condition was evaluated by measuring the amount of GlcNAc in the koji samples over time (Fig. 1C). The measurement of GlcNAc, which is present in the fungus-specific cell wall component chitin, is generally used for evaluating the growth of koji molds because it is difficult to accurately determine the weight of cells grown in solid-state culture (10). The amount of cell growth that was determined based on the GlcNAc content per gram of koji was not significantly different between the two cultivation conditions, indicating that the temperature shift did not markedly affect the cell yield of A. kawachii.

Expression of amylolytic enzymes.

The major component of koji is starch from the polished grains, such as barley and rice. Thus, one of the important features of A. kawachii is the production of amylolytic enzymes, particularly α-amylase, glucoamylase, and α-glucosidase, which belong to the glycoside hydrolase (GH) GH13, GH15, and GH31 protein families in the CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes) database (http://www.cazy.org/Welcome-to-the-Carbohydrate-Active.html). A total of 17 GH13, 2 GH15, and 5 GH31 family proteins were identified in the A. kawachii IFO 4308 genome (see Table S3 and Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

During koji production, A. kawachii produces two types of α-amylases, acid-labile α-amylase (alAA) (AmyA, AKAW_11452) and acid-stable α-amylase (asAA) (AamA, AKAW_02026) (22, 23). asAA is critical for shochu koji production due to large amounts of citric acid produced by A. kawachii. In addition to alAA and asAA, the putative α-amylases AmyC (AKAW_09852), AmyD (AKAW_04889), and AmyE (AKAW_09723) (24) were found in the present genomic analysis (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). In the case of glucoamylase and α-glucosidase, the A. kawachii genome possesses two glucoamylases, GlaA (AKAW_08979) and GlaB (AKAW_07267), and four α-glucosidases, AgdA (AKAW_09853), AgdB (AKAW_05480), AgdC (AKAW_02436), and AgdD (AKAW_10689). As AmyD, AmyE, AgdC, and AgdD do not possess N-terminal signal sequences, these GHs do not appear to be directly involved in the saccharification of extracellular starch. The amyE gene of A. kawachii is located in a gene cluster with agtA and agsE, which are putative cell wall 4-α-glucanotransferase and α-1,3-glucan synthase genes, respectively, an organization that is similar to that of other Aspergillus species (25).

The starch-binding domain (family CBM_20) of amylases is required for the degradation of raw, but not gelatinized, starch (26). Among the GH13, GH15, and GH31 family proteins identified in the A. kawachii genome, only asAA and GlaA possess a starch-binding domain. The number and domain structure of these GH enzymes was highly similar to that of A. niger CBS 513.88 (24). Notably, the glucoamylase GlaB that was found in A. kawachii IFO 4308 is phylogenetically distant from A. oryzae GlaB, which is specifically expressed during solid-state culture and has a crucial role in the digestion of starch during sake production (27, 28) (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

The conditions used in the traditional shochu koji-making process, which involve raising the temperature from 36 to 40°C and subsequently lowering the temperature to 30°C, have been optimized for the effective saccharification of starch and production of citric acid (9, 29). However, among the examined amylolytic enzymes, only the expression of the amyC, agdC, and glaB genes of A. kawachii IFO 4308 were changed significantly (log2 fold change greater than 0.5; q < 0.05) between conditions N and H (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). No marked differences in gene expression of the major amylolytic enzymes, including alAA, asAA, and GlaA, were observed. These results indicated that lowering the temperature in the later stages of koji production is important for producing large amounts of citric acid but does not affect the expression levels of these amylases.

Organic acid production.

A. kawachii produces larger amounts of citric acid under the normal temperature conditions used for shochu koji production than at high temperature (9). The levels of nearly all other examined organic acids of the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle, including pyruvate, citrate, cis-aconitate, isocitrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinate, and malate, did not change significantly under N temperature conditions at 25 and 26.5 h, which represented short-term responses to temperature reduction (Table 2). However, after a further 19 h of cultivation at a lower temperature (N condition), citric acid and isocitrate had accumulated in koji at levels 1.8- and 2.7-fold, respectively, of those detected at higher temperature (H condition). In particular, isocitrate significantly increased under condition N, indicating that the isocitrate dehydrogenation step in the TCA cycle might be the rate-limiting step for the citric acid production under condition H.

TABLE 2.

Metabolites identified in barley koji prepared with A. kawachii

| Compound namea | Concn (nmol/mg koji)b |

Concn ratiob |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N 25 h | N 26.5 h | N 44 h | H 44 h | N 26.5 h/N 25 h | N 44 h/H 44 h | |

| Glucose 6-phosphate | 27 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Fructose 6-phosphate | 6.6 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Fructose 1,6-diphosphate | 4.7 | 2.4 | ND | 1.8 | 0.5 | NA |

| DHAP | 4.8 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 0.6e | 0.5e |

| Glycerol 3-phosphate | 12 | 19 | 36 | 25 | 1.6e | 1.4e |

| 3-Phosphoglycerate | 2.8 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| 6-Phosphogluconate | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Ribulose 5-phosphate | 3.7 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| Ribose 5-phosphate | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.5c |

| Sedoheptulose 7-phosphate | 3.1 | 4 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 2d |

| Pyruvate | 78 | 55 | 18 | 16 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Citrate | 32,444 | 39,597 | 139,094 | 78,370 | 1.2 | 1.8d |

| cis-Aconitate | 509 | 503 | 769 | 826 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Isocitrate | 371 | 383 | 2,644 | 967 | 1 | 2.7c |

| α-Ketoglutarte | 885 | 871 | 689 | 813 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Succinate | 175 | 163 | 105 | 105 | 0.9 | 1 |

| Fumarate | 408 | 269 | 259 | 238 | 0.7e | 1.1 |

| Malate | 7,865 | 7,271 | 4,272 | 5,041 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| GABA | 32 | 27 | 26 | 44 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| UDP | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.6d |

DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid.

Values were determined for N and H conditions at the indicated time points, identified such that N 25 h, for example, indicates the value for the N condition at 25 h. ND, not detected; NA, not available.

P value of <0.001.

P value of <0.01.

P value of <0.05.

Among the other identified metabolites, the levels of glycerol 3-phosphate and glycerol were significantly higher (1.6- and 2.2-fold, respectively), and those of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and trehalose 6-phosphate were significantly lower (0.6- and 0.11-fold, respectively) under condition N at 26.5 h than those detected at 25 h under condition H (Tables 2 and 3). After 44 h of cultivation, the amounts of glycerol 3-phosphate and glycerol under condition N remained significantly higher (1.4- and 1.7-fold, respectively), and those of DHAP and trehalose 6-phosphate remained significantly lower (0.5- and 0.3-fold, respectively) than those under condition H. In addition, the amount of ribulose 5-phosphate was significantly higher (1.5-fold) and that of UDP was significantly lower (0.6-fold) under condition N than those under condition H after 44 h of cultivation.

TABLE 3.

Signal intensity of metabolites in barley koji prepared with A. kawachii

| Compound | Signal intensitya |

Signal ratioa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N 25 h | N 26.5 h | N 44 h | H 44 h | N 26.5 h/N 25 h | N 44 h/H 44 h | |

| ADP-ribose | 5.90E−06 | 5.00E−06 | 9.40E−06 | 4.70E−06 | 0.8 | 2 |

| Glycerol | 5.50E−03 | 1.20 E−02 | 1.70E−02 | 1.00E−02 | 2.2d | 1.7b |

| Trehalose 6-phosphate | 1.80E−04 | 1.90E−05 | 2.50E−05 | 8.50E−05 | 0.11c | 0.3d |

Values were determined for N and H conditions at the indicated time points, identified such that N 25 h, for example, indicates the value for the N condition at 25 h.

P value of <0.001.

P value of <0.01.

P value of <0.05.

Gene expression related to citric acid production.

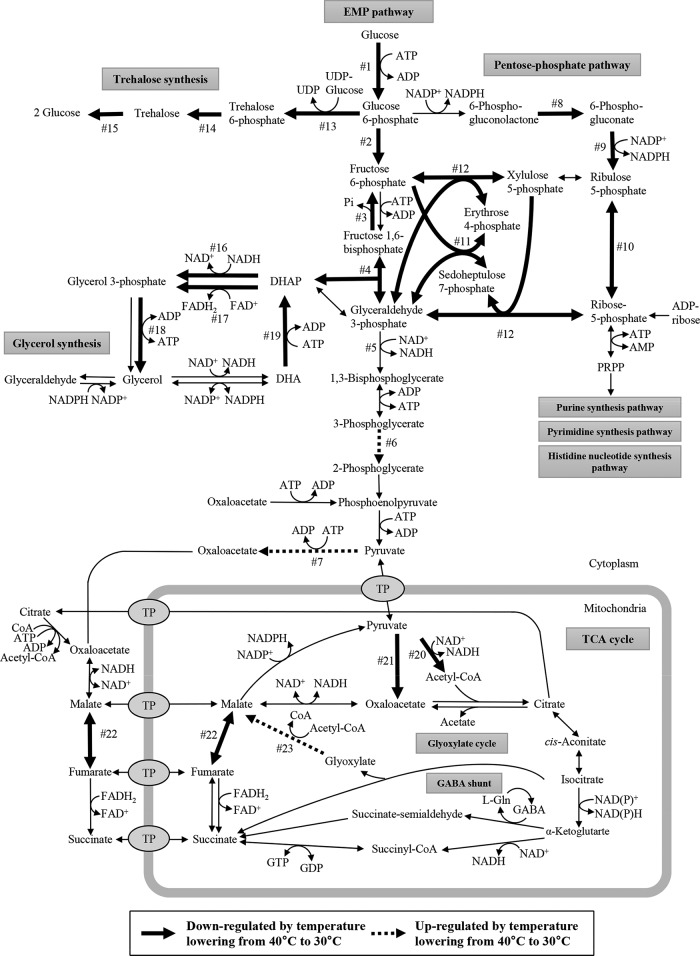

The expression profiles of A. kawachii during solid-state cultivation at 40 and 30°C after 26.5 h were compared to identify temperature-sensitive genes related to citric acid production. Changes in gene expression were considered to be statistically significant if the q value was less than 0.01 and the log2-fold change was less than −0.5 or greater than 0.5. Using these criteria, a total of 1,114 differentially expressed genes, which included 566 upregulated genes and 548 downregulated genes, were identified in the DNA microarray analysis (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Among the differentially expressed genes, 26 genes were mapped to metabolic pathways related to organic acid production (see Fig. S1). The trends of up- and downregulation of these genes, with the exception of one gene (AKAW_02920), were confirmed by real-time RT-PCR analysis (P value < 0.05) (Table 1). Both the microarray and real-time RT-PCR results suggested that the 22 genes related to the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway, pentose phosphate pathway, glycerol pathway, trehalose pathway, and TCA cycle were downregulated after the temperature reduction from 40 to 30°C, whereas 3 genes, phosphoglycerate mutase (AKAW_03245), cytosolic pyruvate carboxylase, (AKAW_00804), and malate synthase (AKAW_08716), were upregulated (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Differentially expressed genes mapped on the proposed metabolic pathways of A. kawachii. Bold and dashed arrows indicate downregulated and upregulated reactions, respectively, 26.5 h after the cultivation temperature lowered from 40 to 30°C during koji production. The numbers (1 to 23) next to the arrows correspond to the numbering of locus tags in Table 1. Abbreviations: CoA, coenzyme A; DHA, dihydroxyacetone; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; Gln, glutamine; PRPP, 5-phospho-alpha-d-ribose 1-diphosphate; TP, transporter protein.

To better understand the mechanisms underlying the accumulation of citric acid in solid-state cultures of A. kawachii, we searched for genes related to citric acid production among the 1,114 differentially expressed genes. In A. niger, the export of citrate from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm is proposed to be one of the major steps controlling citric acid accumulation (30–32). However, the mitochondrial tricarboxylate transporter for citric acid has not been functionally identified in Aspergillus species. The present microarray analysis identified a significant gene expression change (log2 fold change less than −0.5 or greater than 0.5) for 10 putative mitochondrial carrier genes: a putative mitochondrial tricarboxylate transporter (AKAW_03754), which is a homolog of the mitochondrial citrate transporter Ctp1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (33); two putative C4-dicarboxylate transporter/malic acid transport proteins (AKAW_02799 and AKAW_05361); a putative mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier protein (AKAW_02096); and six putative mitochondrial carrier proteins (AKAW_00314, AKAW_04269, AKAW_05213, AKAW_04250, AKAW_08131, and AKAW_09097) (see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

Transcriptional regulation also plays an important role in global metabolic processes in living organisms. In the present gene expression analyses, seven putative transcriptional factors, including several C6 transcription factors (AKAW_03658, AKAW_09811, AKAW_02766, and AKAW_01957), a Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor (AKAW_02903), and two bZIP transcription factors (AKAW_09548 and AKAW_06968), were identified among the genes with significant changes in expression between conditions N and H (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). AKAW_03658, AKAW_09811, AKAW_06968, and AKAW_09548 are predicted to be orthologs of rosA, nosA, atfA, and atfB, respectively, of Aspergillus nidulans and A. oryzae (34–37).

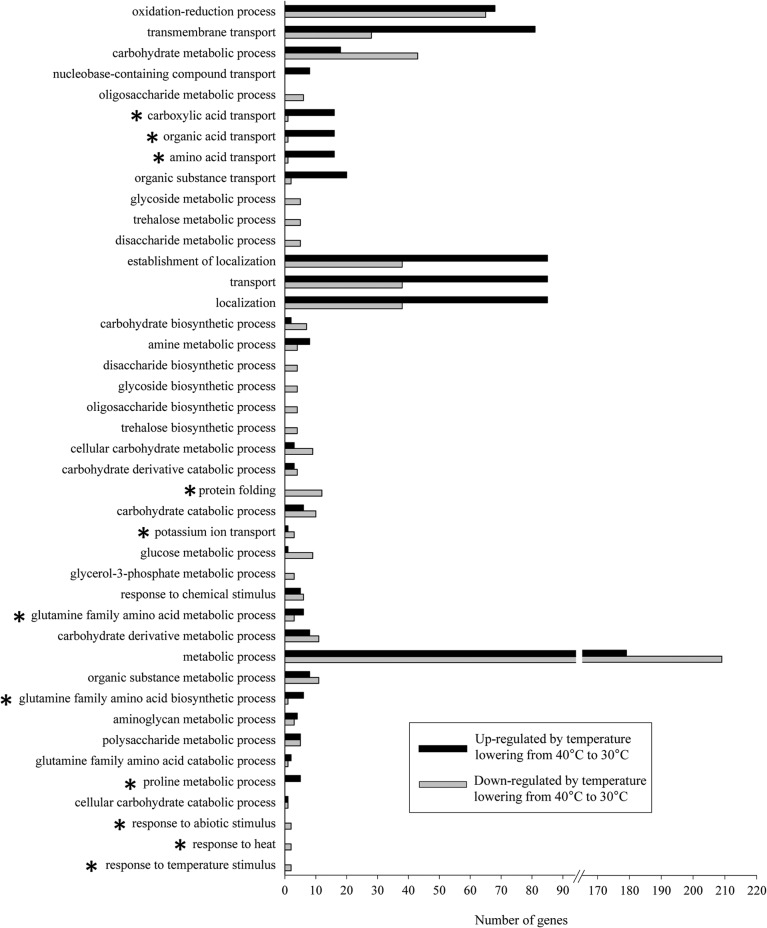

Gene ontology analysis of the 1,114 genes that responded to a decreasing koji cultivation temperature.

To examine the significance of reducing the cultivation temperature during shochu koji production on global gene expression, GO analysis was performed for the 1,114 differentially expressed genes. GO enrichment analysis focusing on biological processes identified 42 enriched GO terms (Fig. 3) (see Data Set S2 in the supplemental material). Because many categories shared the same gene transcripts, overlapping genes were manually removed. Finally, 26 genes related to the EMP pathway, pentose phosphate pathway, glycerol pathway, trehalose pathway, and TCA cycle were included in the GO terms glucose metabolic process (GO:0006006), trehalose metabolic process (GO:0005991), glycerol-3-phosphate metabolic process (GO:0006072), carbohydrate metabolic process (GO:0005975), and metabolic process (GO:0008152). In addition, the phosphoglycerate mutase gene (AKAW_03245) and fumarate hydratase (S)-malate hydrolyase (fumarate-forming) gene (AKAW_08158) were also statistically significantly changed between the two cultivation conditions although these two genes were not included in the GO analysis.

FIG 3.

Biological process GO terms identified by GO enrichment analysis among significantly regulated genes in A. kawachii as determined by lowering the cultivation temperature. The 1,114 differentially expressed genes identified in A. kawachii by lowering the cultivation temperature for 26.5 h were used for the analysis. The GO terms are shown in order of P value (from lowest to highest; all P values are <0.01). *, select genes in this group are listed in Table 4.

With the exception of the genes directly involved in the production of citric acid, we focused on differentially expressed genes that were categorized in the GO terms marked with asterisks in Fig. 3, and the representatives of these were protein folding (GO:0006457), amino acid transport (GO:0006865), glutamine family amino acid metabolic process (GO:0009064), and potassium ion transport (GO:0006813) (Table 4). The protein folding (GO:0006457) functional group consisted of 12 downregulated genes in response to lowered temperature and included genes encoding chaperones, such as mitochondrial DnaJ (DnaJ/Hsp40 family) and calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum-associated chaperone involved in glycoprotein quality control. This result indicated that cultivation at 40°C is a stressful environment for A. kawachii and that chaperones may be involved in adaptation to heat stress conditions. The amino acid transport (GO:0006865) functional group consisted of 17 upregulated and 1 downregulated amino acid transporter, and the glutamine family amino acid metabolic process (GO:0009064) functional group contained 6 upregulated and 3 downregulated genes involved in glutamine and proline metabolism. The observed gene expression changes indicated that amino acid transport and metabolism were activated after the removal of heat stress. Furthermore, the potassium ion transport (GO:0006813) functional group contained one upregulated and three downregulated genes, indicating that potassium ion transport is regulated in response to lowered temperature.

TABLE 4.

Differentially expressed genes related to protein folding, amino acid transport, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, and potassium ion transport in response to lowered cultivation temperature

| Locus tag | Putative function | Fold changee |

GO term(s) (functions) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N 26.5 h/H 26.5 h | N 44 h/H 44 h | |||

| AKAW_00421 | Mitochondrial DnaJ chaperone | 0.44b | 0.58c | Protein folding, temperature stimulus, response to heat, response to abiotic stimulus |

| AKAW_06769 | Mitochondrial protein import protein Mas5 | 0.41b | 0.78 | Protein folding, temperature stimulus, response to heat, response to abiotic stimulus |

| AKAW_00043 | Calnexin precursor | 0.29a | 0.46 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_00798 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B | 0.56b | 0.69 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_01492 | DnaJ and TPR domain protein | 0.47b | 0.66 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_02250 | 10-kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | 0.40b | 0.42c | Protein folding |

| AKAW_03188 | Heat shock protein SSC1, mitochondrial precursor | 0.41b | 0.36b | Protein folding |

| AKAW_03383 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase Cpr7 | 0.17a | 0.58 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_04505 | DnaJ domain protein | 0.51a | 0.65 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_04621 | Heat shock protein 60, mitochondrial precursor | 0.44b | 0.51 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_06285 | Heat shock protein (SspB) | 0.21b | 0.54 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_07910 | DnaJ domain protein Psi | 0.29b | 0.63 | Protein folding |

| AKAW_00265 | Amino acid permease | 2.8b | 2 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_01162 | High-affinity methionine permease | 1.5b | 0.94 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_01807 | Proline-specific permease | 3.4b | 0.52c | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_02935 | Amino acid permease | 2.5b | 1.9c | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_03046 | Amino acid permease | 1.8b | 1.4 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_03122 | Amino acid transporter | 2.0b | 1.7c | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_03197 | GABA permease | 2.9b | 0.56c | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_04302 | Amino acid permease | 0.6b | 0.82 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_05043 | Amino acid transporter | 7.3b | 1.3 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_05161 | Amino acid permease family protein | 3.0b | 2.6c | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_06587 | GABA permease | 2.4b | 1.1 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_06915 | GABA permease GabA | 1.9b | 2.1c | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_07190 | Arginine permease | 2.8b | 1.1 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_07406 | Amino acid permease | 2.6b | 1.9b | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_07981 | GABA permease | 4.7b | 0.51 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_09139 | Proline permease | 4.9b | 0.79 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_09349 | GABA permease | 2.2b | 1.4 | Amino acid transport, organic acid transport, carboxylic acid transport |

| AKAW_00538 | Delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor | 2.5b | 1.1 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, proline metabolic process |

| AKAW_03315 | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase | 2.8b | 0.84 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, proline metabolic process |

| AKAW_03319 | Proline oxidase Put1 | 5.0a | 1.4 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, proline metabolic process |

| AKAW_09924 | Proline oxidase Put1 | 5.9a | 2.1c | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, proline metabolic process |

| AKAW_09925 | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase | 3.3b | 1.4 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, proline metabolic process |

| AKAW_10512 | Acetylglutamate synthase | 0.66b | 1.5 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process, proline metabolic process |

| AKAW_00077 | Glutamine synthetase | 1.6b | 1.3 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process, glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process |

| AKAW_02324 | NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | 0.4b | 0.5c | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process |

| AKAW_05543 | bifunctional pyrimidine biosynthesis protein (PyrABCN) | 0.7b | 0.6c | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process |

| AKAW_00143 | Voltage-gated K+ channel beta subunit | 0.69b | 1.2 | Potassium ion transport |

| AKAW_00287 | Potassium transporter 5 | 1.9a | 3.4c | Potassium ion transport |

| AKAW_03290d | Ankyrin repeat-containing protein | 0.62b | 1.5 | Potassium ion transport |

| AKAW_06471 | Ion channel | 0.49b | 0.92 | Potassium ion transport |

q value of <0.001.

q value of <0.01.

q value of <0.05 statistical significance.

AKAW_03290 shows a best BLASTP hit to potassium transporter Trk2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae although it was annotated just as ankyrin repeat-contaning protein by InterProScan.

Ratios were determined for the indicated conditions and time points, identified such that N 26.5 h, for example, indicates the value for the N condition at 26.5 h.

DISCUSSION

We performed gene expression profiling analysis at conventional and elevated temperatures for barley koji production for shochu brewing to investigate how cultivation temperature influences gene expression in A. kawachii during solid-state cultivation. DNA microarray analysis identified a total of 1,114 differentially expressed genes between the two examined temperature conditions. The observed profile of these genes showed that cultivation at 40°C is stressful for A. kawachii and that heat adaptation leads to reduced citric acid accumulation through activation of pathways branching from glycolysis, as discussed in detail below.

The gene expression profile of A. kawachii when cultivated at 40°C in solid-state culture for an extended period (>24 h) indicates that the pentose phosphate, trehalose, and glycerol pathways are upregulated. Thus, the reduction in citric acid accumulation in barley koji produced under high-temperature conditions may be associated with the enhanced activity of these pathways. Glycerol and trehalose function as stress protectants in microorganisms, including aspergilli. For A. kawachii, cultivation at 40°C appears to induce a stress response because several heat shock proteins and chaperones are significantly upregulated at this temperature, based on the results of GO analysis (Table 4). This finding is in agreement with a previous report that found that heat shock stress induces oxidative stress and an antioxidant response in A. niger, resulting in increased accumulation of the storage carbohydrates trehalose and glycogen (38). It was suggested that trehalose mobilization is required to facilitate cell recovery by A. niger after heat-induced damage (39). In A. niger, cultivation temperature is also an important factor for the production of citric acid, which is optimally produced in liquid culture between 24 and 30°C (40). Here, citrate accumulation by A. kawachii was not observed 1.5 h after the shift to the lower temperature during solid-state cultivation (compare the values for N 26.5 h and N 25 h in Table 2); however, the concentration of metabolites related to glycerol and trehalose metabolism (DHAP, glycerol 3-phosphate, glycerol, and trehalose 6-phosphate) significantly changed between N 26.5 h and N 25 h and between N 44 h and H 44 h (Tables 2 and 3), indicating that changes in the accumulation of these metabolites occur more rapidly than those involved in citrate accumulation. The glycerol pathway is regulated by the high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) signal transduction pathway. Here, the gene expression of ypdA (AKAW_05530), hogA (sakA) (AKAW_06644), and atfA (AKAW_06968) of the HOG pathway were downregulated significantly in A. kawachii (q < 0.01) upon lowering the cultivation temperature from 40 to 30°C (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). AtfA is required for the expression of the NAD-dependent glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (gfdB) and is involved in glycerol accumulation in A. nidulans and A. oryzae (36, 37). Consistent with these functions, the transcriptional level of a putative NAD-dependent glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase-encoding gene (AKAW_10295) of A. kawachii was significantly reduced at the lower cultivation temperature (Table 1). However, the glycerol concentration of koji produced at 30°C (condition N at 44 h) was 1.7-fold higher than the koji made at 40°C (condition H at 44 h) (q < 0.001) (Table 3). This difference might be due to competition for substrates between the glycerol pathway and the enhanced trehalose and/or pentose phosphate pathways when A. kawachii is cultivated at 40°C.

GO analysis also indicated that increasing the cultivation temperature to 40°C is stressful for A. kawachii. The 12 genes related to protein folding were found to be downregulated after the temperature shift from 40°C to 30°C (Table 4). The induction of genes related to protein folding during heat stress response under liquid cultivation condition have also been observed in the other filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Blastocladiella emersonii, and Curvularia protuberata (41–44). In the case of A. fumigatus known as a human-pathogenic fungus, a total of 323 genes were more highly expressed at 48°C than at 37°C (41). They include seven homologs of the 12 differentially expressed protein folding-related genes (AKAW_00421, AKAW_03188, AKAW_03383, AKAW_04621, AKAW_06285, AKAW_06769, and AKAW_07910; BLASTP E values, 0) in A. kawachii, indicating that culture conditions such as liquid or solid-state are not determinant for the expression of these genes. The GO analysis has also shown that the expression of genes related to amino acid transport and biosynthesis of glutamine family amino acids was upregulated upon lowering the cultivation temperature (Table 4), indicating that the growth of A. kawachii appears to be activated by the relief of heat stress. We observed that colony formation by A. kawachii was markedly reduced by heat stress when cells were cultured on yeast-glucose, Czapek-Dox, and minimal agar media (data not shown). However, this finding is inconsistent with the result of GlcNAc analysis, which indicated that high-temperature solid-state cultivation does not significantly affect the growth of A. kawachii. Because the analytical method for GlcNAc surveyed both living and dead cells, the cells carried over after the temperature shift may contribute to higher GlcNAc levels. In addition, the regulation of chitin biogenesis might be affected by cultivation temperature, as evidenced by the fact that the expression of mpkA (AKAW_00136) of the cell wall integrity (CWI) signal transduction pathway was increased 1.8-fold (q < 0.01) by reducing the cultivation temperature to 30°C (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

The enzymatic activity of the prepared barley koji cannot be explained based on gene expression profiles alone. For example, phosphofructokinase is inhibited by citrate, but this inhibition is relieved by the NH4+ ion, AMP, and fructose 2,6-bisphosphate in A. niger (32, 45, 46). In addition, pyruvate kinase activity in A. niger is controlled by various physiological effectors, including H+, Mn2+, K+, Mg2+, and NH4+ (47, 48). The present GO analysis showed that expression of the genes related to potassium ion transport was significantly changed between conditions N and H, a response that might affect the activity of pyruvate kinase in A. kawachii (Table 4). Moreover, A. niger hexokinase is strongly inhibited by physiological concentrations of trehalose 6-phosphate (49). Because the trehalose 6-phosphate concentration in shochu koji was significantly reduced at lower temperature (Table 3), it might have adversely affected the glucose phosphorylation activity in the EMP pathway, leading to downregulation of glycolytic carbon flow.

In conclusion, the present study has determined the gene expression profile of A. kawachii during solid-state culture conditions. The results suggest that the high-temperature solid-state cultivation of A. kawachii adversely affects the central pathways of glucose metabolism, leading to depressed citric acid production. Koji is typically produced using traditional solid-state culture techniques and is widely used in the fermentation industry in Japan. Thus, the gene expression information obtained in this study is expected to improve the understanding of gene regulation during the koji-making process and to allow optimization of the industrially desirable characteristics of A. kawachii. In addition, the present findings also provide insight into the mechanisms underlying the accumulation of citric acid by A. kawachii during solid-state culture.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 24580116 to M.G. and no. 25450106 to T.F.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03483-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Machida M, Yamada O, Gomi K. 2008. Genomics of Aspergillus oryzae: learning from the history of Koji mold and exploration of its future. DNA Res 15:173–183. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitahara K, Yoshida M. 1949. On the so-called Awamori white mold part III. (1) Morphological and several physiological characteristics. J Ferment Technol 27:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada O, Takara R, Hamada R, Hayashi R, Tsukahara M, Mikami S. 2011. Molecular biological researches of Kuro-Koji molds, their classification and safety. J Biosci Bioeng 112:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong SB, Yamada O, Samson RA. 2014. Taxonomic re-evaluation of black koji molds. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:555–561. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frisvad JC, Larsen TO, Thrane U, Meijer M, Varga J, Samson RA, Nielsen KF. 2011. Fumonisin and ochratoxin production in industrial Aspergillus niger strains. PLoS One 6:e23496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbons JG, Rokas A. 2013. The function and evolution of the Aspergillus genome. Trends Microbiol 21:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimoto R, Asano K, Tokashiki T, Onji Y, Hirose-Yasumoto M, Takara R, Toyosato T, Yoshino A, Ikehata M, Ying L, Kumeda Y, Yokoyama K, Takahashi H. 2013. Mycotoxin production and genetic analysis of Aspergillus niger and related species including the kuro-koji mold. JSM Mycotoxins 63:179–186. doi: 10.2520/myco.63.179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwano K, Mikami S, Fukuda K, Nose A, Shiinoki S. 1987. Influence of cultural conditions on various enzyme activities of shochu koji. J Brew Soc Jpn 82:200–204. doi: 10.6013/jbrewsocjapan1915.82.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omori T, Takeshima N, Shimoda M. 1994. Formation of acid-labile α-amylase during barley-koji production. J Ferment Bioeng 78:27–30. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(94)90173-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii F, Ozeki K, Kanda A, Hamachi Y, Nunokawa Y. 1992. A simple method for the determination of grown mycelial content in rice-koji using commercial cell wall lytic enzyme, yatalase. J Brew Soc Jpn 87:757–759. doi: 10.6013/jbrewsocjapan1988.87.757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reissig JL, Storminger JL, Leloir LF. 1955. A modified colorimetric method for the estimation of N-acetylamino sugars. J Biol Chem 217:959–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Futagami T, Mori K, Yamashita A, Wada S, Kajiwara Y, Takashita H, Omori T, Takegawa K, Tashiro K, Kuhara S, Goto M. 2011. Genome sequence of the white koji mold Aspergillus kawachii IFO 4308, used for brewing the Japanese distilled spirit shochu. Eukaryot Cell 10:1586–1587. doi: 10.1128/EC.05224-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen MR, Nielsen ML, Nielsen J. 2008. Metabolic model integration of the bibliome, genome, metabolome and reactome of Aspergillus niger. Mol Syst Biol 4:178. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flipphi M, Sun J, Robellet X, Karaffa L, Fekete E, Zeng AP, Kubicek CP. 2009. Biodiversity and evolution of primary carbon metabolism in Aspergillus nidulans and other Aspergillus spp. Fungal Genet Biol 46:S19–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. 2000. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris MA, Clark J, Ireland A, Lomax J, Ashburner M, Foulger R, Eilbeck K, Lewis S, Marshall B, Mungall C, Richter J, Rubin GM, Blake JA, Bult C, Dolan M, Drabkin H, Eppig JT, Hill DP, Ni L, Ringwald M, Balakrishnan R, Cherry JM, Christie KR, Costanzo MC, Dwight SS, Engel S, Fisk DG, Hirschman JE, Hong EL, Nash RS, Sethuraman A, Theesfeld CL, Botstein D, Dolinski K, Feierbach B, Berardini T, Mundodi S, Rhee SY, Apweiler R, Barrell D, Camon E, Dimmer E, Lee V, Chisholm R, Gaudet P, Kibbe W, Kishore R, Schwarz EM, Sternberg P, Gwinn M, et al. 2004. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machida M, Asai K, Sano M, Tanaka T, Kumagai T, Terai G, Kusumoto K-I, Arima T, Akita O, Kashiwagi Y, Abe K, Gomi K, Horiuchi H, Kitamoto K, Kobayashi T, Takeuchi M, Denning DW, Galagan JE, Nierman WC, Yu J, Archer DB, Bennett JW, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Fedorova ND, Gotoh O, Horikawa H, Hosoyama A, Ichinomiya M, Igarashi R, Iwashita K, Juvvadi PR, Kato M, Kato Y, Kin T, Kokubun A, Maeda H, Maeyama N, Maruyama J, Nagasaki H, Nakajima T, Oda K, Okada K, Paulsen I, Sakamoto K, Sawano T, Takahashi M, Takase K, Terabayashi Y, Wortman JR, et al. 2005. Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae. Nature 438:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pel HJ, de Winde JH, Archer DB, Dyer PS, Hofmann G, Schaap PJ, Turner G, de Vries RP, Albang R, Albermann K, Andersen MR, Bendtsen JD, Benen JAE, van den Berg M, Breestraat S, Caddick MX, Contreras R, Cornell M, Coutinho PM, Danchin EGJ, Debets AJM, Dekker P, van Dijck PWM, van Dijk A, Dijkhuizen L, Driessen AJM, d' Enfert C, Geysens S, Goosen C, Groot GSP, de Groot PWJ, Guillemette T, Henrissat B, Herweijer M, van den Hombergh JPTW, van den Hondel CAMJJ, van der Heijden RTJM, van der Kaaij RM, Klis FM, Kools HJ, Kubicek CP, van Kuyk PA, Lauber J, Lu X, van der Maarel MJEC, Meulenberg R, Menke H, Mortimer MA, Nielsen J, Oliver SG, et al. 2007. Genome sequencing and analysis of the versatile cell factory Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88. Nat Biotechnol 25:221–231. doi: 10.1038/nbt1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerqueira GC, Arnaud MB, Inglis DO, Skrzypek MS, Binkley G, Simison M, Miyasato SR, Binkley J, Orvis J, Shah P, Wymore F, Sherlock G, Wortman JR. 2014. The Aspergillus Genome Database: multispecies curation and incorporation of RNA-Seq data to improve structural gene annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D705–D710. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker SE. 2006. Aspergillus niger genomics: past, present and into the future. Med Mycol 44(Suppl 1):S17–S21. doi: 10.1080/13693780600921037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneko A, Sudo S, Takayasu-Sakamoto Y, Tamura G, Ishikawa T, Oba T. 1996. Molecular cloning and determination of the nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding an acid-stable α-amylase from Aspergillus kawachii. J Ferment Bioeng 81:292–298. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(96)80579-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suganuma T, Fujita K, Kitahara K. 2007. Some distinguishable properties between acid-stable and neutral types of alpha-amylases from acid-producing koji. J Biosci Bioeng 104:353–362. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan XL, van der Kaaij RM, van den Hondel CA, Punt PJ, van der Maarel MJ, Dijkhuizen L, Ram AF. 2008. Aspergillus niger genome-wide analysis reveals a large number of novel alpha-glucan acting enzymes with unexpected expression profiles. Mol Genet Genomics 279:545–561. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Groot PW, Brandt BW, Horiuchi H, Ram AF, de Koster CG, Klis FM. 2009. Comprehensive genomic analysis of cell wall genes in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol 46(Suppl 1):S72–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto M, Semimaru T, Furukawa K, Hayashida S. 1994. Analysis of the raw starch-binding domain by mutation of a glucoamylase from Aspergillus awamori var. kawachi expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:3926–3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hata Y, Ishida H, Ichikawa E, Kawato A, Suginami K, Imayasu S. 1998. Nucleotide sequence of an alternative glucoamylase-encoding gene (glaB) expressed in solid-state culture of Aspergillus oryzae. Gene 207:127–134. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hata Y, Ishida H, Kojima Y, Ichikawa E, Kawato A, Suginami K, Imayasu S. 1997. Comparison of two glucoamylases produced by Aspergillus oryzae in solid-state culture (koji) and in submerged culture. J Ferment Bioeng 84:532–537. doi: 10.1016/S0922-338X(97)81907-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajiwara Y, Takeshima N, Ohba H, Omori T, Shimoda M, Wada H. 1997. Production of acid-stable α-amylase by Aspergillus kawachii during barley Shochu-Koji production. J Ferment Bioeng 84:224–227. doi: 10.1016/S0922-338X(97)82058-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres N. 1994. Modelling approach to control of carbohydrate metabolism during citric acid accumulation by Aspergillus niger. I. Model definition and stability of the steady state. Biotechnol Bioeng 44:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres N. 1994. Modelling approach to control of carbohydrate metabolism during citric acid accumulation by Aspergillus niger. II. Sensitivity analysis. Biotechnol Bioeng 44:112–118. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karaffa L, Kubicek CP. 2003. Aspergillus niger citric acid accumulation: do we understand this well working black box? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 61:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan RS, Mayor JA, Gremse DA, Wood DO. 1995. High level expression and characterization of the mitochondrial citrate transport protein from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 270:4108–4114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vienken K, Scherer M, Fischer R. 2005. The Zn(II)2Cys6 putative Aspergillus nidulans transcription factor repressor of sexual development inhibits sexual development under low-carbon conditions and in submersed culture. Genetics 169:619–630. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.030767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vienken K, Fischer R. 2006. The Zn(II)2Cys6 putative transcription factor NosA controls fruiting body formation in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 61:544–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagiwara D, Asano Y, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. 2008. Characterization of bZip-type transcription factor AtfA with reference to stress responses of conidia of Aspergillus nidulans. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72:2756–2760. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakamoto K, Iwashita K, Yamada O, Kobayashi K, Mizuno A, Akita O, Mikami S, Shimoi H, Gomi K. 2009. Aspergillus oryzae atfA controls conidial germination and stress tolerance. Fungal Genet Biol 46:887–897. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrashev RI, Pashova SB, Stefanova LN, Vassilev SV, Dolashka-Angelova PA, Angelova MB. 2008. Heat-shock-induced oxidative stress and antioxidant response in Aspergillus niger 26. Can J Microbiol 54:977–983. doi: 10.1139/W08-091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svanström A, Melin P. 2013. Intracellular trehalase activity is required for development, germination and heat-stress resistance of Aspergillus niger conidia. Res Microbiol 164:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitos PA, Campbell JJ, Tomlinson N. 1953. Influence of temperature on the trace element requirements for citric acid production by Aspergillus niger. Appl Microbiol 1:156–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, Berriman M, Abe K, Archer DB, Bermejo C, Bennett J, Bowyer P, Chen D, Collins M, Coulsen R, Davies R, Dyer PS, Farman M, Fedorova N, Fedorova N, Feldblyum TV, Fischer R, Fosker N, Fraser A, García JL, García MJ, Goble A, Goldman GH, Gomi K, Griffith-Jones S, Gwilliam R, Haas B, Haas H, Harris D, Horiuchi H, Huang J, Humphray S, Jiménez J, Keller N, Khouri H, Kitamoto K, Kobayashi T, Konzack S, Kulkarni R, Kumagai T, Lafton A, Latgé JP, Li W, Lord A, Lu C, et al. 2005. Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 438:1151–1156. doi: 10.1038/nature04332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georg RC, Gomes SL. 2007. Transcriptome analysis in response to heat shock and cadmium in the aquatic fungus Blastocladiella emersonii. Eukaryot Cell 6:1053–1062. doi: 10.1128/EC.00053-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albrecht D, Guthke R, Brakhage AA, Kniemeyer O. 2010. Integrative analysis of the heat shock response in Aspergillus fumigatus. BMC Genomics 11:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morsy MR, Oswald J, He J, Tang Y, Roossinck MJ. 2010. Teasing apart a three-way symbiosis: transcriptome analyses of Curvularia protuberata in response to viral infection and heat stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 401:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arts E, Kubicek CP, Röhr M. 1987. Regulation of phosphofructokinase from Aspergillus niger: effect of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate on the action of citrate, ammonium ions and AMP. Microbiology 133:1195–1199. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-5-1195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Habison A, Kubicek CP, Röhr M. 1983. Partial purification and regulatory properties of phosphofructokinase from Aspergillus niger. Biochem J 209:669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mesecar AD, Nowak T. 1997. Metal-ion-mediated allosteric triggering of yeast pyruvate kinase. 2. A multidimensional thermodynamic linked-function analysis. Biochemistry 36:6803–6813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meixner-Monori B, Kubicek CP, Röhr M. 1984. Pyruvate kinase from Aspergillus niger: a regulatory enzyme in glycolysis? Can J Microbiol 30:16–22. doi: 10.1139/m84-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panneman H, Ruijter GJ, van den Broeck HC, Visser J. 1998. Cloning and biochemical characterisation of Aspergillus niger hexokinase: the enzyme is strongly inhibited by physiological concentrations of trehalose 6-phosphate. Eur J Biochem 258:223–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.