Abstract

Two reporter strains were established to identify novel biomolecules interfering with bacterial communication (quorum sensing [QS]). The basic design of these Escherichia coli-based systems comprises a gene encoding a lethal protein fused to promoters induced in the presence of QS signal molecules. Consequently, these E. coli strains are unable to grow in the presence of the respective QS signal molecules unless a nontoxic QS-interfering compound is present. The first reporter strain designed to detect autoinducer-2 (AI-2)-interfering activities (AI2-QQ.1) contained the E. coli ccdB lethal gene under the control of the E. coli lsrA promoter. The second reporter strain (AI1-QQ.1) contained the Vibrio fischeri luxI promoter fused to the ccdB gene to detect interference with acyl-homoserine lactones. Bacteria isolated from the surfaces of several marine eukarya were screened for quorum-quenching (QQ) activities using the established reporter systems AI1-QQ.1 and AI2-QQ.1. Out of 34 isolates, two interfered with acylated homoserine lactone (AHL) signaling, five interfered with AI-2 QS signaling, and 10 were demonstrated to interfere with both signal molecules. Open reading frames (ORFs) conferring QQ activity were identified for three selected isolates (Photobacterium sp., Pseudoalteromonas sp., and Vibrio parahaemolyticus). Evaluation of the respective heterologously expressed and purified QQ proteins confirmed their ability to interfere with the AHL and AI-2 signaling processes.

INTRODUCTION

Quorum sensing (QS) is the cell-cell communication between bacteria that allows the perception of population density by small signaling molecules—so-called autoinducers—and modifies gene expression in response to the population density. It controls a wide spectrum of processes and phenotypic behaviors, including stress resistance, production of toxins and secondary metabolites, pathogenicity, swarming, and biofilm formation (for a review, see references 1 and 2). In addition to playing important roles in intraspecies and interspecies communication, QS is also involved in host-microbe interactions (3–5). Intraspecific communication of Gram-negative bacteria is based on the production and perception of acylated homoserine lactones (AHLs) synthesized by LuxI homologs. Increasing intracellular concentrations of diffusible AHLs with higher cell densities are perceived by binding of the AHLs to the cognate receptor (e.g., LuxR in Vibrio fischeri), resulting in activation or inhibition of target gene transcription (6, 7). Interspecific communication between different species within one habitat has been demonstrated to depend on the synthesis and detection of the universal autoinducer-2 (AI-2), which can be inhibited by furanones (8, 9). The perception of these signal molecules is achieved either by a two-component regulatory system (e.g., in Vibrio harveyi, where the induced phosphorylation cascade finally results in the induction of specific target genes) (10), or by transportation of the signal molecule into the cell (e.g., in Escherichia coli, where binding to the corresponding receptor protein relieves the repression of target genes) (4, 9, 11).

QS controls various population density-dependent processes, such as biofilm formation on surfaces. Because biofilms potentially have harmful effects on living organisms (in the case of pathogenic bacteria) and on yields in the industrial sector, an attractive novel strategy to control biofilm formation based on QS interference (quorum quenching [QQ]) has been proposed and established (12–19). Synthesis of QS-interfering compounds has been demonstrated for bacteria and eukaryotes (20–24), leading to the hypothesis that eukaryotes have evolved such defense mechanisms as a strategy for protection and inhibition of association with bacterial pathogens (25). The best-studied example of naturally occurring QQ activities in eukaryotes is the halogenated furanones synthesized by the marine red alga Delisea pulchra that protect the alga against overgrowth with bacteria by antagonistically outcompeting autoinducers (26–33). However, other organisms besides eukaryotes have taken advantage of developing QQ mechanisms for protection against pathogenic bacteria; indeed, bacteria themselves have developed and benefited from QQ strategies. Several interference mechanisms based on the degradation or modification of signal molecules have been described (recently summarized in references 16 and 19). One well-studied example of AHL degradation, the AHL lactonases, such as those from Bacillus spp., represent highly specific QQ proteins capable of hydrolyzing the lactone ring of AHLs and producing nonfunctional acyl homoserines (24, 34, 35). Additionally, AHL acylases, initially discovered in Variovorax paradoxus, have also been found in other bacteria and degrade AHL by hydrolyzing the amide linkage (36–39). In addition to these examples, a series of AHL analogues with varying side chain lengths and substitutions have been synthesized de novo and are highly effective in inhibiting the QS systems of several Gram-negative bacteria (30, 40–44). The few known examples of interference with AI-2 often represent more indirect mechanisms, such as inhibition of AI-2 synthesis or phosphorylation processes involved in interspecies signal processes (9, 14, 45, 46). However, several synthetic AI-2 analogues have been shown to compete with natural AI-2 for binding to the corresponding receptor (47–50). Natural AI-2 signal degradation has been exclusively shown for E. coli LsrG, which catalyzes the cleavage of phosphorylated AI-2, producing 2-phosphoglycolic acid and consequently terminating induction of the lsr operon (49, 51). This capability to sequester but also destroy AI-2 is proposed to enable enterobacteria to respond to competitor bacteria by eliminating the competitors' intracellular communication capabilities (49, 51). The current knowledge of QQ mechanisms is summarized in two recent reviews that also address and discuss the potential of QS inhibition for use in novel therapies to target and potentially control bacterial pathogenicity (16, 19).

In the present study, we aimed to identify novel nontoxic biomolecules derived from bacterial consortia on marine eukaryotes interfering with AHL- and AI-2-based QS. Reporter strains have been established for AHL and AI-2 interference based on the strategy developed and used for the QSIS1 reporter strain by Rasmussen et al. (52); the method allows the identification of AHL QS-interfering activity. Use of these reporter strains enabled us to identify several bacteria isolated from the surfaces of simple marine eukaryotes that synthesize compounds that interfered with AI-2- and/or AHL-based cell-cell communication (QQ activity). Several of these natural quenching proteins were identified, and their activities were verified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The transformation of plasmid DNA into E. coli cells was performed as previously described (53).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pCC1FOS | Fosmid vector | Epicentre, Madison, WI |

| pCRII-TOPO | TA-cloning vector | Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany |

| pZErO-2 | Cloning vector; ccdB under transcriptional control of the lac promoter | Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany |

| pDrive | Cloning vector (ampicillin and kanamycin resistance) | Qiagen, Hilden, Germany |

| pMAL-c2X | Cloning vector fusing malE N terminus | NEB, Frankfurt, Germany |

| pRS442 | luxIR fragment TA cloned in pDrive | This study |

| pRS349 | lsrA promoter TA cloned in pDrive | This study |

| pRS444 | luxIR fragment directed, cloned into pDrive KpnI/EcoRI | This study |

| pRS353 | lsrA promoter directed, cloned into pDrive | This study |

| pRS488 | ccdB under transcriptional control of the luxI promoter | This study |

| pRS489 | ccdB under transcriptional control of the lsrA promoter | This study |

| pRS622 | QQ-No.34a fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS623 | QQ-No.34b fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS795 | QQ-No.16a fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS796 | QQ-No.16b fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS797 | QQ-No.16c fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS798 | QQ-No.16d fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS799 | QQ-No.10a fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS800 | QQ-No.10b fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS801 | QQ-No.10c fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| pRS802 | QQ-No.10d fused to malE in pMAL-c2X | This study |

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| K-12 MG1655 | 111 | |

| DH5α | λ− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | 112 |

| EPI300-T1R | F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galKλ- rpsL nupG trfA tonA dhfr | Epicentre, Madison, WI |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | 113 |

| XL1-Blue | endA1 gyrA96(nalR) thi-1 recA1 relA1 lac glnV44 F′[::Tn10 proAB+ lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15] hsdR17(rK− mK+) | Stratagene, La Jolla, CA |

| AI1-QQ.1 | E. coli DH5α/pRS488; reporter strain to identify AHL-QQ compounds | This study |

| AI2-QQ.1 | E. coli DH5α/pRS489; reporter strain to identify AI-2-QQ compounds | This study |

| pZErO-2 control | E. coli XL1-Blue/pZErO-2; control strain | This study |

| Vibrio fischeri | DSM 2168 | DSMZa |

| Serratia liquefaciens ATCC 27592 | DSM 4487 | DSMZ |

| Klebsiella oxytoca M5a1 | 114 | |

| Bacillus subtilis | DSM 4424 | DSMZ |

| Staphylococcus aureus | DSM 346 | DSMZ |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | DSM 1707 | DSMZ |

DSMZ, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany.

Growth media.

The media used in this study included Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (54) and marine seawater medium (MB) (pH 7.6) using commercial available mixtures (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and Reef Crystals (Aquarium Systems, France; 15 g/liter) supplemented with yeast extract (1 g/liter) and peptone (5 g/liter). The following media were used for biofilm formation assays: AB medium {200 ml solution A [2 g/liter (NH4)2SO4, 6 g/liter Na2HPO4, 3 g/liter KH2PO4, and 3 g/liter NaCl] combined with 800 ml solution B [0.1 M CaCl2, 1 M MgCl2, and 3 mM FeCl3 supplemented with 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose]}, Caso bouillon (17 g/liter casein peptone, 3 g/liter soybean peptone, 5 g/liter NaCl, 2.5 g/liter K2HPO4, and 2.5 g/liter glucose), and GC medium (1% [vol/vol] glycerol and 0.3% [wt/vol] Casamino Acids) (55). Where indicated, the medium was supplemented with the following final concentrations of antibiotics: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 30 μg/ml; or chloramphenicol, 12.5 μg/ml.

Sampling and enrichment from surfaces of marine macroalgae and invertebrates.

Bacteria were isolated from the macroalgae Fucus vesiculosus, Fucus serratus, and Polysiphonia stricta; the blue mussel Mytilus edulis; and different life stages of the moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita (polyp, ephyra, and medusa). Marine eukaryotes were in general sampled from the Baltic Sea at sites located near Kiel, Germany, from May to September 2008 and 2009. A. aurita polyps from the White Sea (Kandalaksha, Russia), eastern Atlantic (Roscoff, France), and North Sea (Helgoland, Germany) were provided by T. C. G. Bosch (University of Kiel). The sampled marine organisms were thoroughly rinsed three times with filtered (0.22 μm) seawater to remove loosely attached microorganisms. An area of approximately 5 cm2 was swabbed with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator (except for polyps and ephyrae). The swabbed bacteria were streaked on agar plates using two different media (Vaatanen nine-salt solution marine medium [VNSS] [56] and the less complex MB) and incubated at 20°C for at least 2 days. The streaks were repeated at least three times until pure single colonies were obtained. The pure cultures were analyzed for 16S rRNA genes and taxonomically classified via BLAST search using the NCBI 16S rRNA database. Input sequence lengths varied from 900 to 1,300 bp. The closest relatives of the isolates are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Screening for quorum-quenching-active bacteria isolated from surfaces of marine eukaryotes

| Isolate no. | Identification by 16S rRNA gene analysisa | Host organism | AHL-quenching activityb |

AI-2-quenching activityb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | Supernatant | Cell extract | Supernatant | |||

| 2 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | A. aurita, medusa | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | Pseudoalteromonas tunicata | A. aurita, medusa | − | − | − | + |

| 8 | Tenacibaculum sp. | A. aurita, polyp | − | − | + | + |

| 9 | Vibrio natriegens | A. aurita, polyp | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | A. aurita, polyp | + | + | − | − |

| 11 | Vibrio sp. | A. aurita, polyp | + | + | − | + |

| 16 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | P. stricta | + | + | + | + |

| 17 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | P. stricta | + | + | − | − |

| 18 | Pseudomonas putida | P. stricta | + | + | + | + |

| 20 | Marinobacterium rhizophila | P. stricta | − | − | − | + |

| 21 | Marinobacterium rhizophila | P. stricta | − | − | − | + |

| 23 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | F. vesiculosus | − | − | + | + |

| 25 | Bacillus firmus | F. vesiculosus | − | + | − | + |

| 30 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | F. vesiculosus | + | + | + | + |

| 31 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | F. serratus | − | + | − | + |

| 33 | Maribacter sp. | F. serratus | − | + | − | + |

| 34 | Photobacterium sp. | F. serratus | + | + | + | + |

See Table S1 in the supplemental material.

QQ activities were determined using the reporter strains AI1-QQ.1 and AI2-QQ.1. +, activity; −, no activity.

DNA isolation.

High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was isolated from 3-ml overnight cultures using the AquaPure Genomic DNA Kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Fosmid DNA was isolated from 5-ml overnight cultures using the High-Speed-Plasmid minikit (Avegene, Taiwan, China).

16S rRNA gene analysis.

16S rRNA genes were PCR amplified from 5 ng isolated genomic DNA using the bacterium-specific primer 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and the universal primer 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (57), resulting in a 1.5-kb bacterial PCR fragment. The fragment was cloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). DNA sequences were determined by the sequencing facility at the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology, University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany (IKM).

Construction of genomic large-insert libraries.

Fosmid libraries of Photobacterium sp. (isolate no. 34), Pseudoalteromonas sp. (isolate no. 16), and V. parahaemolyticus (isolate no. 10) were constructed using the Copy Control Fosmid Library Production Kit and vector pCC1FOS (Epicentre, Madison, WI) with the modifications described by Weiland et al. (58).

Construction of reporter plasmids.

A plasmid-encoded reporter for monitoring interference with quorum sensing was established based on the strategy used for the QSIS1 reporter by Rasmussen et al. (52). The two reporter plasmids (pRS488 and pRS489) were constructed as follows (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). PCR amplification using the primer set PluxI (5′-GGTACCACCTGTAGGATCGTACAGGT-3′) and PluxR (5′-GAATTCTTAATTTTTAAAGTATGGGCAATCAATTG-3′) including additional restriction sites (sequences are underlined) and genomic DNA from V. fischeri (DSM 2168) amplified a 977-bp fragment comprising the V. fischeri luxRI gene, including the promoter of the lux operon (59, 60) and additional restriction sites for KpnI at the 5′ end and for EcoRI at the 3′ end. PCR amplification with the primer set PlsrAfor (5′-GGTACCCGCGACCTGTTCTTCTT-3′) and PlsrArev (5′-GAATTCCATATTTCCCCCGTTCAGTT-3′) and genomic DNA from E. coli K-12 MG1655 produced the 319-bp E. coli lsrA promoter region (11) containing additional 5′ KpnI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sites. The lethal gene ccdB was amplified with the primer pair PccdBfor (5′-GAATTCAGGGACTGGTGAATACACCTATAAAAGAGAGAGCC-3′) and PccdBrev (5′-GAGCTCCAGGCCTGACATTTATATTC-3′) using the cloning vector pZErO-2 (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) as a template. The 309-bp ccdB PCR fragment without the promoter contained restriction sites for EcoRI at the 5′ end and SacI at the 3′ end. Amplification of the fragments was performed using Taq polymerase (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and a 30-cycle standard PCR protocol with a primer-annealing temperature of 50°C. PCR fragments containing the respective promoters were TA cloned into pDrive (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), resulting in pRS442 containing the luxIR fragment, including the luxI promoter, and pRS349 including the lsrA promoter. KpnI/EcoRI fragments from pRS442 (luxIR) and pRS349 (lsrA) were directionally cloned into KpnI/EcoRI-digested pDrive, resulting in pRS444 (luxIR) and pRS353 (lsrA), respectively. Next, the linear PCR fragment containing the lethal gene ccdB was digested using EcoRI/SacI, purified, and cloned into EcoRI/SacI-digested pRS444 and pRS353, respectively. The fusion of ccdB to the luxI promoter resulted in the vector pRS488, and the fusion of ccdB to the lsrA promoter resulted in pRS489. Transformation of the constructed reporter plasmids into E. coli DH5α resulted in the following reporter strains: AI1-QQ.1 containing pRS488 and AI2-QQ.1 containing pRS489.

Quorum-quenching assay.

QQ screening plates were prepared as follows: LB agar containing 0.8% agar at 50°C was supplemented with final concentrations of 100 μM N-(β-ketocaproyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C6-HSL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany), 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml kanamycin, and 10% (vol/vol) exponentially growing culture of the reporter strain AI1-QQ.1. LB agar plates were coated with the agar mixture. AI-2 quorum-quenching plates were prepared similarly, but the agar was supplemented with final concentrations of 50 mM 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3-furanone (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany), 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml kanamycin, and 5% (vol/vol) exponentially growing culture of the reporter strain AI2-QQ.1. After 10 min, 5 μl of the test substances was applied, followed by a 1-h incubation at room temperature (RT) and overnight incubation at 37°C. QQ activities were visualized by growth of the respective reporter strain.

Maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins (5 μl of 50-µg/µl solutions) of putative QQ clones [E. coli BL21(DE3)/pRS622, pRS623, and pRS795 to pRS802) were additionally tested with the control strain XL1-Blue/pZErO-2 to exclude the possibility of effects on the toxicity of the lethal protein (e.g., by degradation or transportation out of the cell). Control plates were prepared with LB agar containing 0.8% agar at 50°C supplemented with final concentrations of 10 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside), 30 μg/ml kanamycin, and 10% (vol/vol) exponentially growing culture of the control strain XL1-Blue/pZErO-2.

Preparation of cell extracts and cell-free culture supernatants from isolates.

Isolated bacteria were grown in 5 ml MB overnight at 30°C and 120 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 × g, and the culture supernatant was subsequently filtered using 0.2-μm centrifugal filter units (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The cell extract was prepared from the cell pellet using the Geno/Grinder 2000 (BT&C/OPS Diagnostics, Bridgewater, NJ). The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and glass beads (0.1 mm and 2.5 mm) were added prior to mechanical cell disruption for 6 min at 1,300 strokes/min at RT. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g and 4°C for 45 min, the cell extracts were filtered through 0.2-μm filter units. Culture supernatants and cell extracts were stored for up to 1 week at 4°C without significant loss of activity, as determined by the reporter strain assay.

Identification of QQ-ORFs.

To identify the respective open reading frames (ORFs) conferring the QQ activity of isolates no. 34 (Photobacterium sp.), no. 16 (Pseudoalteromonas sp.), and no. 10 (V. parahaemolyticus), genomic fosmid libraries were constructed as described above (see “Construction of genomic large-insert libraries”). To identify fosmid clones with QQ activity, approximately 96 clones were initially assayed in parallel. Individual cultures grown in 150 μl medium in microtiter plates (MTPs) were combined and centrifuged at 4,000 × g and 4°C for 30 min to prepare cell-free culture supernatants and cell extracts as described above.

Molecular characterization of quorum-sensing-interfering clones.

To identify ORFs conferring QQ activity, two alternative methods were used.

(i) Subcloning.

The fosmid clones were grown in 20 ml LB medium supplemented with 12.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37°C and 150 rpm overnight. Fosmids were isolated and digested with EcoRI to completeness. The respective restriction fragments were analyzed on 1% agarose gels, excised, and purified using NucleoSpin ExtractII (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The purified fragments were cloned into the EcoRI-digested pDrive cloning vector (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The resulting clones were analyzed to determine their QQ activities (see above), and the pDrive inserts of QQ-positive clones were sequenced by the sequencing facility at the IKM using the primer set M13(−20)for (5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3′) and M13(−24)rev (5′-AACAGCTATGACCATG-3′) and subsequently generated primers. Sequence analysis was performed using CodonCode Aligner software (CodonCode Corporation, Dedham, MA) to assemble all the sequences deriving from primer walk events. The contigs obtained were scanned for putative quorum-quenching ORFs using ORF Finder (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA).

(ii) In vitro transposon mutagenesis.

Identification of the ORFs involved in quorum-sensing interference was performed using the EZ::TN5<Kan-2>Insertion Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA) for in vitro transposon mutagenesis according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transposon insertion clones were screened for the loss of quorum-quenching activity. The respective flanking regions of the Tn5 insertion of identified fosmid inserts were sequenced on both strands using the transposon-specific primers KAN-2 FP-1 (5′-ACCTACAACAAAGCTCTCATCAACC-3′) and KAN-2 RP-1 (5′-GCAATGTAACATCAGAGATTTTGAG-3′) provided by the manufacturer. Sequence analysis and assembly were performed as described above.

Cloning of identified QQ-ORFs in pMAL-c2X and purification.

Putative QQ-ORFs were amplified in a standard PCR with ORF-specific primers with the addition of additional restriction recognition sites flanking the ORFs (listed in Table 2). The purified fragments were TA cloned into vector pCRII-TOPO (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). The ORFs were subsequently excised using the additional restriction sites and cloned into the respective digested pMAL-c2X (NEB, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pMAL-c2X fusion vectors expressing putative QQ-ORFs were grown in 1 liter LB medium at 37°C. Expression of proteins was induced with 300 μM IPTG when the cultures reached a turbidity at 600 nm of ∼0.6. Cell extracts were prepared by disrupting the cells in CB buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) using a French pressure cell with an internal cell pressure of 20,000 lb/in2 followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g. MBP fusion proteins were purified from the supernatant by affinity chromatography with amylose resin and 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4) supplemented with 10 mM maltose as the elution buffer, according to the manufacturer's protocol (NEB, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Protein samples were dialyzed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C overnight using Visking dialysis tubing (16 mm; molecular weight cutoffs [MWCO], 12,000 to 14,000; 25 Å; Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) to get rid of maltose. Protein aliquots were stored in 1× PBS supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) glycerol at −20°C. Protein purity and molecular weight were determined by SDS-PAGE (12%), followed by Coomassie blue staining.

Biofilm formation assays.

The biofilm-forming strains E. coli K-12 MG1655, Klebsiella oxytoca M5aI, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus were grown in 96-well plates in minimal medium (B. subtilis and E. coli, AB medium; S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, Caso bouillon; K. oxytoca M5a1, GC minimal medium) for 24 h at 80 rpm and 37°C, with the exception of B. subtilis and K. oxytoca M5aI, which were grown at 30°C. Purified MBP-QQ proteins were added to freshly inoculated cultures in amounts of 10 μg, 50 μg, and 100 μg in 150 μl in MTPs. After 24 h of incubation, the liquid cultures were removed and the wells were washed twice with H2O. Developed biofilms sticking to the well surfaces were stained with 200 μl of 0.1% crystal violet solution (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 10 min at RT. After removing the crystal violet solution by washing twice with H2O, the stained biofilms were air dried. A total of 200 μl of 96% ethanol was added to each stained well, and the dye was solubilized by incubating for 15 min at RT. Biofilm formation was monitored and quantified by measuring the absorbance at 590 nm as described by Mack and Blain-Nelson and others (61, 62).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers were obtained for bacterial isolates 1 to 34 (JX287298 to JX287331).

RESULTS

Establishing reporter systems to identify novel quorum-sensing-interfering compounds.

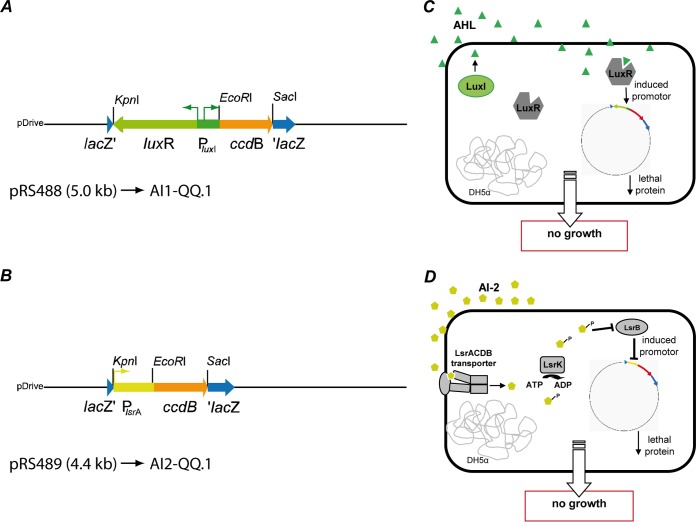

Two types of reporter systems enabling the identification of QS-interfering compounds were constructed. The construction and establishment of the reporter system is generally based on the innovative strategy of Rasmussen and collaborators (52) used for the establishment of so-called quorum-sensing inhibition (QSI) selector strains. These strains comprise a gene encoding a lethal protein fused to an AHL-controlled promoter and consequently result in growth arrest and cell death in the presence of AHLs. Here, we constructed E. coli-based reporter strains aiming to identify AHL- and AI-2-interfering biomolecules. The construction of the respective reporter plasmids was designed in such a way as to allow quick and easy substitutions of the respective promoter and the novel selected lethal gene, as described in Materials and Methods (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The lethal gene ccdB selected for the generation of the reporter plasmids was derived from the toxin-antitoxin locus ccdA-ccdB of the E. coli F plasmid encoding the cell-killing protein CcdB, which in the absence of CcdA inactivates gyrase and results in cell death (63–65). The gene was fused to the QS-controlled promoters PluxI of V. fischeri and PlsrA of E. coli, as outlined in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. It was crucial for the functionality of the luxI promoter to additionally include the gene encoding the receptor LuxR upstream of PluxI (Fig. 1A, reporter plasmid pRS488). The reporter plasmids (depicted in Fig. 1A and B) were introduced into E. coli DH5α because the strain is unable to synthesize acyl-homoserine lactones due to the absence of the luxI gene (66) and has additionally lost the ability to synthesize AI-2 due to a frameshift mutation within the luxS gene encoding the corresponding AI-2 synthase (67). The presence of the chromosomal lsr operon (lsrACDBFGE) and the divergently transcribed lsrRK in the E. coli background (14, 68) ensured AI-2-dependent regulation of the lethal gene under the transcriptional control of the E. coli lsrA promoter and thus allowed detection of AI-2-interfering compounds (see Fig. 1B, reporter plasmid pRS489).

FIG 1.

Reporter systems. Two E. coli reporter strains containing a gene encoding a lethal protein under the control of a promoter inducible by the respective QS signal molecules were constructed. (A) The V. fischeri luxI promoter ultimately expressing the lethal gene ccdB (pRS488). (B) Constructing the strain with the lethal gene ccdB (pRS489) under the control of the AI-2-inducible lsrA promoter. (C and D) E. coli strains carrying the fusion reporters on a plasmid are unable to grow in the presence of the respective signal molecules unless nontoxic interfering molecules are present. The reporter systems detect compounds for AHL quenching (C) or interference with the signal molecule AI-2 (D).

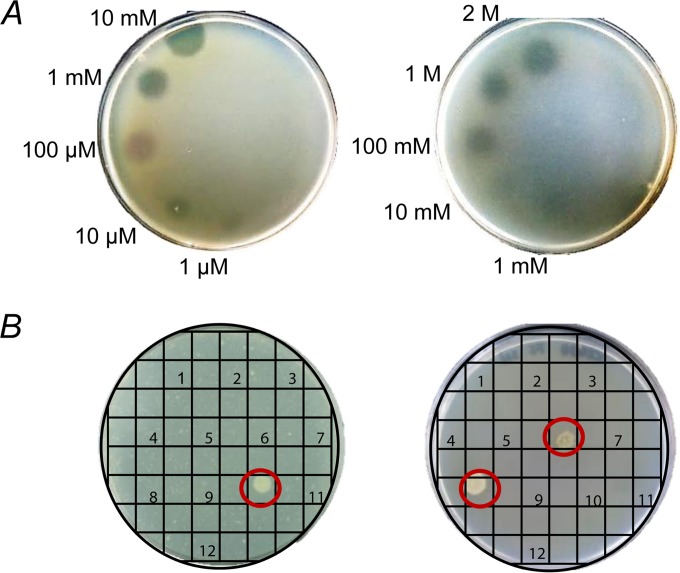

Expression of the lethal gene under the control of the luxI promoter in the resulting reporter strain AI1-QQ.1 (DH5α/pRS488) was induced by N-(β-keto-caproyl)-l-homoserine lactone, the structural analogue of the natural AHL 3-oxo-C6-homoserine lactone (69) (Fig. 1C). The reporter strain AI2-QQ.1 (DH5α/pRS489) containing the lsrA promoter fusion was induced by 5-methyl-4-hydroxy-3-furanone, which has been proposed to be the effective form of the native AI-2 (8) (Fig. 1D). The individual concentrations of the signal molecules required for complete growth inhibition of the respective reporter strains on plates were determined as depicted in Fig. 2A. Growth inhibition of the AI1-QQ.1 reporter strain was achieved when 5 μl N-(β-ketocaproyl)-l-homoserine lactone was applied at concentrations of ≥10 μM. In contrast, because inhibition of AI-2-QQ.1 required significantly higher concentrations of the signal molecule, the application of at least 10 mM 5-methyl-4-hydroxy-3-furanone (5 μl) was necessary (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Validation of the reporter systems. (A) Growth inhibition of the E. coli reporter strains AI1-QQ.1 (left) and AI2-QQ.1 (right) grown in agar was tested by applying 5 μl of increasing concentrations of the autoinducers N-(β-ketocaproyl)-l-homoserine lactone (1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM) and 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3-furanone (10 mM, 100 mM, 1 M, and 2 M), respectively. (B) Cell extracts and culture supernatants (5 μl) from bacterial isolates were screened for QS-interfering activities with the respective reporter strains. The test plates used were covered with agar containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml kanamycin, 0.1 mM N-(β-ketocaproyl)-l-homoserine lactone, and 10% (vol/vol) exponentially growing reporter strain AI1-QQ.1 (left ) or 50 mM 5-methyl-4-hydroxy-3-furanone and 5% (vol/vol) exponentially growing reporter strain AI2-QQ.1 (right). The original test plates illustrate reestablishment of growth of the reporter strains after 24 h of incubation at 37°C by interference with the signal molecule that is present (circled).

To detect QS-interfering activities or compounds, exponentially growing reporter strains were included in agar in the presence of optimized final concentrations of signal molecules to completely inhibit the growth of the respective reporter strains [100 μM N-(β-ketocaproyl)-l-homoserine lactone for AI1-QQ and 50 mM 5-methyl-4-hydroxy-3-furanone for AI2-QQ]. The application of test substances on the agar allowed the detection of QQ activities by growth reestablishment of the reporter strains, as illustrated in Fig. 2B, showing the original test plates. Additional controls using E. coli DH5α without a reporter plasmid excluded toxic growth effects due to the presence of the respective concentrations of autoinducers (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Evaluating the ability of bacteria associated with surfaces of marine eukaryotes to interfere with cell-cell communication.

Overall, 34 isolates of bacteria associated with surfaces of marine eukaryotes—A. aurita, M. edulis, P. stricta, F. vesiculosus, and F. serratus—were isolated and subsequently identified by 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). A total of 35% were classified as Pseudoalteromonas sp. and 20% as Vibrio sp.; other identified isolates mainly belong to the Gammaproteobacteria. Numerous representatives of the identified genera have been frequently isolated from marine waters and have been found in association with marine invertebrates, algae, plants, and animals (70, 71).

All identified isolates were screened for naturally occurring QS-interfering activities using the reporter strains AI1-QQ.1 and AI2-QQ.1, cell extracts, and culture supernatants of exponentially growing isolates as described in Materials and Methods. This demonstrated that 2 isolates exclusively exhibited AHL interference activity and 5 exclusively exhibited AI-2 interference activity, whereas 10 showed simultaneous interference with AHL and AI-2, including Pseudoalteromonas, Vibrio, Maribacter, Photobacterium, and Bacillus species (Table 2). Remarkably, different Vibrio species isolated from the surfaces of A. aurita polyps showed either exclusive interference with AHL or interference with both AHL and AI-2, indicating that different interference mechanisms may have evolved under diverse environmental conditions and various compositions of microbiota. This was also reflected within the Pseudoalteromonas species isolated from macroalgae. It is notable that 50% of the isolates evaluated showed QQ activity, demonstrating an unexpectedly high frequency of QQ-active bacteria in such microbial consortia and highlighting their potential as rich sources for compounds capable of interfering with bacterial cell-cell communication.

Identification and verification of the ORFs conferring QQ activity on selected isolates.

Three isolates exhibiting quenching activities against AHL and AI-2 were selected for further molecular characterization: (i) Photobacterium sp. isolated from the surface of the brown seaweed F. serratus (isolate no. 34; GenBank accession no. JX287331), (ii) Pseudoalteromonas sp. isolated from the surface of the red alga P. stricta (isolate no. 16; GenBank accession no. JX287313), and (iii) V. parahaemolyticus isolated from the surfaces of A. aurita polyps (isolate no. 10; GenBank accession no. JX287307). Genomic fosmid libraries were generated to identify the respective ORFs conferring QQ activity. Cell extracts and culture supernatants of 1,920 individual fosmid clones from each genomic library were screened for QQ activity as described above, resulting in identification of five fosmids conferring QQ activities (Table 3). Three fosmid clones (no. 34 7/B4, no. 16 4/B6, and no. 16 4/C5) showed simultaneous AHL- and AI-2-quenching activities, whereas the remaining two, generated from V. parahaemolyticus (no. 10 9/H3 and no. 10 9/H4), revealed exclusive AHL-quenching activities. Further analysis of cell extracts and supernatants conferring QQ activity demonstrated that heat inactivation and proteinase K treatment of all cell extracts and supernatants resulted in a complete loss of QQ activity, strongly arguing for protein-dependent QQ activity.

TABLE 3.

Identification and characterization of quorum-quenching ORFs derived from three bacterial isolates

| Bacterial isolate (isolate no.) | QQ-active fosmid clone (QQ activity) | Designation of QQ-ORFa (accession no.; MBP fusion plasmid) | Closest homolog (% identity) | QQ activity of MBP fusion proteinb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photobacterium sp. (34) | 7/B4 (AHL + AI-2) | QQ-No.34a (JX306042; pRS622) | IcmF-like protein from Vibrio sp. (53) | AHL + AI-2 |

| QQ-No.34b (JX306043; pRS623) | ImpA-like protein from Vibrio sp. (45) | ND | ||

| Pseudoalteromonas sp. (16) | 4/B6 (AHL + AI-2) | QQ-No.16a (JX306044; pRS795) | Membrane transport protein vfu_B01239 from V. furnissii (76) | AHL + AI-2 |

| 4/C5 (AHL + AI-2) | QQ-No.16b (JX306045; pRS796) | Hypothetical protein vfu_B01276 from V. furnissii (87) | AHL + AI-2 | |

| QQ-No.16c (JX306046; pRS797) | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase from V. furnissii (92) | ND | ||

| QQ-No.16d (JX306047; pRS798) | Hypothetical protein vfu_B01063 from V. furnissii (75) | AHL + AI-2 | ||

| V. parahaemolyticus (10) | 9/H4 (AHL) | QQ-No.10a (JX306048; pRS799) | Hypothetical protein V12G01_07378 from V. alginolyticus (90) | AHL |

| QQ-No.10b (JX306049; pRS800) | Virulence-mediating protein VirC from V. alginolyticus (87) | ND | ||

| QQ-No.10c (JX306050; pRS801) | Hypothetical protein V12G01_06641 from V. alginolyticus (90) | AHL | ||

| 9/H3 (AHL) | QQ-No.10d (JX306051; pRS802) | Putative permease from V. alginolyticus (96) | ND | |

| QQ-No.10e (JX306052; pRS803) | Sigma cross-reacting protein 27A from V. alginolyticus (90) | ND |

The QQ-ORFs identified by subcloning and/or transposon mutagenesis were characterized after heterologous expression of the respective MBP fusion proteins.

The QQ activities of the MBP fusion proteins were analyzed using reporter strains AI1-QQ.1 and AI2-QQ.2. ND, not detectable.

The identification of the respective ORFs mediating the QQ activities of these fosmid clones was achieved by subcloning (in the case of no. 34 7/B4) or transposon mutagenesis, followed by sequence analysis of flanking regions of the transposon insertions of fosmids that lost their QQ activity (see Materials and Methods). In total, 11 putative QQ-ORFs were identified from the three fosmid clones (schematically depicted in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). All putative QQ-ORFs were PCR cloned into the pMAL-c2X expression vector, and the resulting QQ proteins N-terminally fused to the MBP were purified by affinity chromatography. Purified MBP-QQ fusion proteins (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) were evaluated regarding their quenching activity using the reporter strains AI1-QQ.1 and AI2-QQ.1 and demonstrated quenching activities against AHL and AI-2 for proteins QQ-No.34a, QQ-No.16a, QQ-No.16b, and QQ-No.16d; in contrast, QQ-No.10a and QQ-No.10c showed exclusive AHL-quenching activities (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). BLAST analysis revealed that QQ-No.34a showed homology to a small portion of the 128.9-kDa IcmF-like protein from Vibrio sp., which is an intracellular multiplication F (IcmF) family protein representing a conserved component of a newly identified type VI secretion system. QQ-No.16a/b/d showed high homology to a transporter component and two uncharacterized proteins from Vibrio furnissii, and QQ-No.10a/c showed homology to hypothetical proteins from Vibrio alginolyticus (summarized in Table 3; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). However, the QQ activity of the 5 remaining ORFs was not confirmed (Table 3); this lack of confirmation might be due to potential polar effects of the transposon insertion (e.g., on genes encoding transcriptional regulators or interruption of regulatory elements, such as noncoding regulatory RNAs, in the initial identification process of putative QQ-ORFs by transposon mutagenesis) (see above).

Additional control experiments were performed to verify that the identified QQ activities of the putative QQ proteins (Table 3) were not based on effects on the toxicity of the lethal protein CcdB. The vector pZErO-2 includes the IPTG-inducible lac promoter fused to the lethal gene ccdB in addition to a kanamycin resistance cassette. When induced with 10 mM IPTG, the respective XL1-Blue control strain carrying pZErO-2 did not grow in the agar. The presence of all tested putative QQ proteins did not result in reestablishment of the growth of this control strain (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), strongly arguing that the active QQ proteins did not affect the toxicity of CcdB.

Evaluating the inhibitory effects of the identified QQ proteins on biofilm formation.

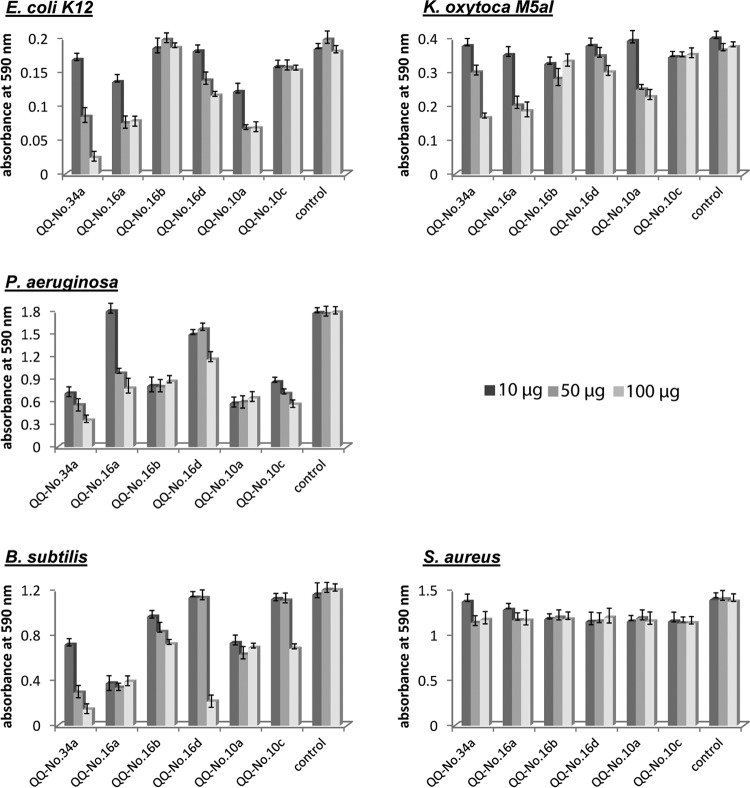

To further verify QQ activity, the influence of MBP-QQ fusion proteins on one of the QS-dependent processes (biofilm formation) was evaluated using five biofilm-forming model organisms, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria of medical or biotechnological interest (E. coli MG1655, K. oxytoca M5aI, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis, and S. aureus). In contrast to most Gram-negative bacteria, E. coli does not synthesize AHLs (72), and the formation of microcolonies and biofilms is dependent on AI-2 (73–75). The important pathogen K. oxytoca is also not capable of synthesizing AHLs; in this pathogen, the initial steps of biofilm formation (e.g., attachment at the substratum and the formation of microcolonies) and the maturation rate of developing biofilms to form three-dimensional structures are induced by AI-2 (76, 77). The opportunistic bacterium P. aeruginosa coordinates the formation and structure of biofilms, swarming motility, exopolysaccharide production, and cell aggregation by N-(3-oxo-dodecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone-dependent quorum sensing (78–80). For the Gram-positive bacteria B. subtilis and S. aureus, both oligopeptides and AI-2 are required as signaling molecules to induce biofilm formation (81–83); however, the extents to which the different signaling molecules are involved in the formation of biofilms in these organisms have not been elucidated.

Purified QQ MBP fusion proteins (10 μg, 50 μg, and 100 μg) were added to freshly inoculated cultures grown in a total volume of 250 μl in 96-well plates. After 24 h, the relative amounts of synthesized biofilms were quantified using the crystal violet biofilm assay (Fig. 3). QQ-No.34a, QQ-No.16a, and QQ-No.10a strongly affected biofilm formation by E. coli MG1655 when supplemented with 50 μg of protein. With the largest amount of QQ-No.34a, biofilm formation was reduced to 10%. Similar but less prominent effects were obtained for K. oxytoca M5a1. Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa was efficiently inhibited in the presence of all the QQ proteins except QQ-No.16d, reducing biofilm formation to 30% (QQ-No.34a and QQ-No.10a/c). Remarkably, all analyzed QQ proteins affected biofilm formation in the Gram-positive model system B. subtilis to various extents, possibly due to interference with AI-2-based biofilm formation. In contrast, no effects on biofilm formation by S. aureus were detectable.

FIG 3.

Inhibition of biofilm formation by identified MBP-QQ proteins using five model systems. E. coli, K. oxytoca, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis, and S. aureus were grown in 96-well plates in defined medium (E. coli and B. subtilis, AB medium; K. oxytoca, GC medium; S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, Caso bouillon) for 24 h at 80 rpm and 37°C, with the exception of K. oxytoca and B. subtilis, which were incubated at 30°C. Purified MBP-QQ proteins (10, 50, and 100 μg) were added to freshly inoculated cultures, and the controls were incubated with the same amount of purified MBP to evaluate potential effects based on the MBP fusion and/or the buffer system used. After 24 h of incubation, the established biofilms were stained with crystal violet and subsequently resolved in 96% ethanol. The absorbance of the solutions was measured at 590 nm. The data represent the averages of the results of three independent experiments with standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Establishment of biosensors for identifying novel AHL and AI-2 quorum-quenching compounds.

We established two reporter strains that enabled the detection of natural AHL- and AI-2-interfering biomolecules with the aim of identifying novel biomolecules capable of interfering with bacterial communication. The design of the reporter strains was based on the strategy underlying the quorum-sensing inhibitor selector strain for AHL interference (QSIS1) developed by Rasmussen et al. (52), which has been successfully used for the identification of both synthetic compounds and natural compounds from extracts of plants and fungi conferring AHL-quenching activities (52, 84). We successfully established and validated reporter strains for the detection of AHL and AI-2 interference using the lethal gene ccdB from E. coli instead of the Serratia liquefaciens phlA gene used in QSIS1 (52). After evaluation and verification of the established ccdB-based screening system, we successfully identified several proteins from bacteria isolated from the surfaces of marine eukarya that interfered with AHL and/or AI-2 QS (Table 3).

In recent years several reporter systems have been developed to detect inhibitors and activators of QS based on fusion of a QS-controlled promoter to a reporter gene. These strains often lack the ability to produce native QS signals; however, they are able to respond to exogenous autoinducers, often with a clearly detectable phenotype, such as violacein pigment production in Chromobacterium violaceum CV026 (85, 86) and bioluminescence production in V. harveyi (87) or Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136 (88). Using such reporter strains, numerous compounds degrading or modifying AHL have been identified, including signal molecules and AHL analogues (reviewed in references 16 and 19). However, only a few AI-2-quenching compounds—mostly small antagonistic molecules—have been identified to date that directly or indirectly interfere with the AI-2 QS processes, probably due to the comparatively little knowledge about AI-2 QS systems in various bacteria and the lack of appropriate reporter systems (summarized in references 16 and 19). A few reporter systems for the detection of AI-2-like compounds have been reported that in principle can be used for identification of AI-2-quenching activities. One example is a V. harveyi-based reporter system with a mutated autoinducer synthase (LuxS) that can be used to detect external accumulation of AI-2, leading to bioluminescence (67). A second reporter system is based on lacZ fusion to the E. coli AI-2-inducible promoter lsrA (11, 17). The current knowledge of QS interference mechanisms for the different QS processes in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, as well as the establishment of different reporter systems, is summarized in a recent review by LaSarre and Federle (19), who also discuss the potential use of QS inhibition for the control of bacterial pathogenicity.

In general, almost all of the reported screening systems used today are based on the disappearance of the reporter signal in a growing reporter strain to identify QS-interfering compounds. Thus, the drawback of such reporter systems is that factors other than QQ compounds can also cause a significant reduction of the signal, including growth inhibition or toxic substances (such as antibiotics) (52). In contrast, the established screening systems presented in this study circumvent these problems by using selection for growth in the presence of nontoxic QQ compounds. This enables the rapid identification of QS-interfering compounds from isolates, extracts, and (meta)genomic libraries with high numbers of clones; moreover, some false-positive results, including those that are due to toxic effects, are excluded due to the selection for growth.

High identification frequencies of QQ activities among bacteria associated with marine eukaryotes.

The present study demonstrated that QS-interfering bacteria can be isolated from surfaces of marine eukaryotes with high frequencies. Out of 34 isolates, 17 with high quenching activities were identified. These bacteria mainly belonged to the Gammaproteobacteria (including Pseudoalteromonas and Vibrio), which are typically associated with marine animals and plants and are often pathogens (89–93). In general, the colonization of living surfaces by microorganisms is a typical aquatic and marine phenomenon, because marine environments are highly competitive and a sessile mode of life in a biofilm is energetically advantageous and favorable (94). Various bacteria are able to form biofilms on the surfaces of eukaryotes, including marine algae, diatoms, and sponges, to foul the inhabited surfaces (95). Thus, many marine organisms have evolved efficient strategies to combat bacterial overgrowth (e.g., the production of inhibitory compounds [96, 97] that are either toxic to bacteria, such as antibiotics [98, 99], or interfere with bacterial cell-cell communication to prevent the establishment of biofilms on surfaces [100, 101]). Thus, bacteria associated with eukaryotes are attracting attention because they are remarkable candidates for rich sources of novel natural bioactive compounds for use in biotechnology or in novel potential therapies targeting pathogenic bacteria (102–105).

Our finding of unusually high frequencies of bacteria with significant QS-interfering activities within marine consortia is in accordance with recent reports on the occurrence of marine bacteria with AHL-QQ activities in pelagic and marine surface-associated communities (17, 105). Using C. violaceum CV026 (85, 86) (see above) as a reporter strain, Romero et al. (105) demonstrated that 24 out of 166 cultivable bacterial strains isolated from different marine microbial communities eliminated or significantly reduced AHLs, a significantly higher percentage than that reported for soil isolates (106, 107). Moreover, analysis of marine metagenomes revealed a high occurrence of genes encoding lactonases and acylases (17), both known to interfere with AHL QS. These findings reinforce the potential ecological role of the QS and QQ processes in marine environments, particularly in dense microbial communities on biological surfaces and particles. They may further suggest that interference with AHL and AI-2 has been established as a strategy in marine environments to achieve competitive advantages on surfaces. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that QS signal degradation activity might to some extent also be due to the use of AHL as an additional carbon and energy source.

Quorum-quenching ORFs with biotechnological implications.

The detailed analysis of the three selected quorum-quenching-active isolates revealed that most of the identified QQ-ORFs simultaneously interfered with AHL and AI-2 QS; this result was verified in the biofilm formation assays. Unfortunately, the respective genes mostly encoded proteins with unknown functions and showed no conclusive homology to known catalytic domains. Consequently, although QS interference has been demonstrated and verified, the mechanisms by which these proteins exhibit apparent QQ activity remains highly speculative. In general, one can assume that modification or degradation of signaling molecules (AHL and AI-2), as well as interference with the respective signal receptor or the transporter, is a potential mechanism for interference. However, interference at other steps of the QS pathway is conceivable and has to be elucidated by further analysis. Currently, the molecular mechanisms causing functionality of the QQ proteins identified in this report can only be hypothesized based on sequence homologies. For example, QQ-No.34a of Photobacterium sp. shows sequence similarity (43%) to a type IV secretion protein from Vibrio based on the presence of an IcmF-like domain. This common domain has been identified in more than 650 bacteria (108) and represents a conserved region located toward the C-terminal end of several hypothetical bacterial proteins with unknown functions. A few resemble the ImcF protein, which has been proposed to be involved in Vibrio cholerae cell surface reorganization, resulting in increased adherence to epithelial cells and increased conjugation frequency (109). Proteins with this conserved domain tend to be associated with type VI secretion systems (110). This conjecture clearly demonstrates that elucidating the molecular mechanism of the respective QQ activity is not possible without further detailed biochemical analyses. Furthermore, knowledge of the molecular interference mechanisms responsible for the QQ activity is particularly crucial for an assessment of their potential for use in biotechnology.

Evidence for successful use in the prevention of harmful biofilm formation was obtained by effective inhibition of biofilms upon the addition of the purified QQ proteins to growing cultures (Fig. 3). Differences between the identified QQ proteins in their modes and their effectiveness in biofilm inhibition were detected, indicating that one or two of them have promising potential for use in biotechnological processes. One potential application in the case of stabile QQ proteins is the immobilization of particles on surfaces (e.g., tubes in medical use). However, further in vivo and in vitro studies and detailed biochemical analyses need to be performed to gain detailed insights into the molecular mechanisms of their QQ activities and quorum-quenching efficiencies under biotechnologically relevant conditions.

Conclusions.

We succeeded in establishing novel reporter systems for the detection of AHL and AI-2 interference and identified several QQ-ORFs from marine isolates. Although the molecular mechanisms still need to be elucidated, the identified QQ-ORFs may have potential utility in biotechnology. Our finding of unusually high frequencies of both AI-2- and AHL-interfering activities within microbial consortia on the surfaces of marine eukaryotes indicates that QS signals and signal modification play an important role in prokaryotic-eukaryotic interactions in the marine environment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rebekka Kraemer, Diana Meske, and Frauke Symanowski for providing several bacterial isolates from marine eukaryotes. We thank the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology in Kiel, Germany, for providing Sanger sequencing, supported in part by the DFG Cluster of Excellence Inflammation at Interfaces and Future Ocean.

The work has received financial support from the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Bildung as part of the GenoMik Transfer Netzwerk.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03290-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackwell HE, Fuqua C. 2011. Introduction to bacterial signals and chemical communication. Chem Rev 111:1–3. doi: 10.1021/cr100407j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrout JD, Tolker-Nielsen T, Givskov M, Parsek MR. 2011. The contribution of cell-cell signaling and motility to bacterial biofilm formation. MRS Bull 36:367–373. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galloway WR, Hodgkinson JT, Bowden SD, Welch M, Spring DR. 2011. Quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria: small-molecule modulation of AHL and AI-2 quorum sensing pathways. Chem Rev 111:28–67. doi: 10.1021/cr100109t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira CS, Thompson JA, Xavier KB. 2013. AI-2-mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37:156–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens AM, Schuster M, Rumbaugh KP. 2012. Working together for the common good: cell-cell communication in bacteria. J Bacteriol 194:2131–2141. doi: 10.1128/JB.00143-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell RJ, Lee SK, Kim T, Ghim CM. 2011. Microbial linguistics: perspectives and applications of microbial cell-to-cell communication. BMB Rep 44:1–10. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith D, Wang JH, Swatton JE, Davenport P, Price B, Mikkelsen H, Stickland H, Nishikawa K, Gardiol N, Spring DR, Welch M. 2006. Variations on a theme: diverse N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria. Sci Prog 89:167–211. doi: 10.3184/003685006783238335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winzer K, Hardie KR, Burgess N, Doherty N, Kirke D, Holden MT, Linforth R, Cornell KA, Taylor AJ, Hill PJ, Williams P. 2002. LuxS: its role in central metabolism and the in vitro synthesis of 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3(2H)-furanone. Microbiology 148:909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira CS, Santos AJ, Bejerano-Sagie M, Correia PB, Marques JC, Xavier KB. 2012. Phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system regulates detection and processing of the quorum sensing signal autoinducer-2. Mol Microbiol 84:93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rui F, Marques JC, Miller ST, Maycock CD, Xavier KB, Ventura MR. 2012. Stereochemical diversity of AI-2 analogs modulates quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Escherichia coli. Bioorg Med Chem 20:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue T, Zhao L, Sun H, Zhou X, Sun B. 2009. LsrR-binding site recognition and regulatory characteristics in Escherichia coli AI-2 quorum sensing. Cell Res 19:1258–1268. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong KW, Koh CL, Sam CK, Yin WF, Chan KG. 2012. Quorum quenching revisited—from signal decays to signalling confusion. Sensors (Basel) 12:4661–4696. doi: 10.3390/s120404661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu P, Li M. 2012. Recent progresses on AI-2 bacterial quorum sensing inhibitors. Curr Med Chem 19:174–186. doi: 10.2174/092986712803414187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques JC, Lamosa P, Russell C, Ventura R, Maycock C, Semmelhack MF, Miller ST, Xavier KB. 2011. Processing the interspecies quorum-sensing signal autoinducer-2 (AI-2): characterization of phospho-(S)-4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione isomerization by LsrG protein. J Biol Chem 286:18331–18343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy V, Adams BL, Bentley WE. 2011. Developing next generation antimicrobials by intercepting AI-2 mediated quorum sensing. Enzyme Microb Technol 49:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero M, Acuna L, Otero A. 2012. Patents on quorum quenching: interfering with bacterial communication as a strategy to fight infections. Recent Pat Biotechnol 6:2–12. doi: 10.2174/187220812799789208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero M, Martin-Cuadrado AB, Otero A. 2012. Determination of whether quorum quenching is a common activity in marine bacteria by analysis of cultivable bacteria and metagenomic sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:6345–6348. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01266-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bijtenhoorn P, Mayerhofer H, Muller-Dieckmann J, Utpatel C, Schipper C, Hornung C, Szesny M, Grond S, Thurmer A, Brzuszkiewicz E, Daniel R, Dierking K, Schulenburg H, Streit WR. 2011. A novel metagenomic short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence on Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 6:e26278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaSarre B, Federle MJ. 2013. Exploiting quorum sensing to confuse bacterial pathogens. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:73–111. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jermy A. 2011. Antimicrobials: disruption of quorum sensing meets resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:767. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simanski M, Babucke S, Eberl L, Harder J. 2012. Paraoxonase 2 acts as a quorum sensing-quenching factor in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 132:2296–2299. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elias M, Tawfik DS. 2012. Divergence and convergence in enzyme evolution: parallel evolution of paraoxonases from quorum-quenching lactonases. J Biol Chem 287:11–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.257329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christiaen SE, Brackman G, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. 2011. Isolation and identification of quorum quenching bacteria from environmental samples. J Microbiol Methods 87:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bijtenhoorn P, Schipper C, Hornung C, Quitschau M, Grond S, Weiland N, Streit WR. 2011. BpiB05, a novel metagenome-derived hydrolase acting on N-acylhomoserine lactones. J Biotechnol 155:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacheco AR, Sperandio V. 2009. Inter-kingdom signaling: chemical language between bacteria and host. Curr Opin Microbiol 12:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Nys R, Wright AD, König GM, Sticher O. 1993. New halogenated furanones from the marine alga Delisea pulchra (cf. fimbriata). Tetrahedron 49:11213–11220. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)81808-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Givskov M, de Nys R, Manefield M, Gram L, Maximilien R, Eberl L, Molin S, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. 1996. Eukaryotic interference with homoserine lactone-mediated prokaryotic signalling. J Bacteriol 178:6618–6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjelleberg S, Steinberg G, Givskov M, Gram L, Manefield M, de Nys R. 1997. Do marine natural products interfere with prokaryotic AHL regulatory systems? Aquat Microb Ecol 13:85–93. doi: 10.3354/ame013085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren D, Sims JJ, Wood TK. 2001. Inhibition of biofilm formation and swarming of Escherichia coli by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Environ Microbiol 3:731–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manefield M, Rasmussen TB, Henzter M, Andersen JB, Steinberg P, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M. 2002. Halogenated furanones inhibit quorum sensing through accelerated LuxR turnover. Microbiology 148:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen TB, Manefield M, Andersen JB, Eberl L, Anthoni U, Christophersen C, Steinberg P, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M. 2000. How Delisea pulchra furanones affect quorum sensing and swarming motility in Serratia liquefaciens MG1. Microbiology 146:3237–3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones MB, Jani R, Ren D, Wood TK, Blaser MJ. 2005. Inhibition of Bacillus anthracis growth and virulence-gene expression by inhibitors of quorum-sensing. J Infect Dis 191:1881–1888. doi: 10.1086/429696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Case RJ, Longford SR, Campbell AH, Low A, Tujula N, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. 2011. Temperature induced bacterial virulence and bleaching disease in a chemically defended marine macroalga. Environ Microbiol 13:529–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong YH, Gusti AR, Zhang Q, Xu JL, Zhang LH. 2002. Identification of quorum-quenching N-acyl homoserine lactonases from Bacillus species. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:1754–1759. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1754-1759.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalia VC, Purohit HJ. 2011. Quenching the quorum sensing system: potential antibacterial drug targets. Crit Rev Microbiol 37:121–140. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2010.532479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leadbetter JR, Greenberg EP. 2000. Metabolism of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by Variovorax paradoxus. J Bacteriol 182:6921–6926. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.24.6921-6926.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang SY, Hadfield MG. 2003. Composition and density of bacterial biofilms determine larval settlement of the polychaete Hydroides elegans. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 260:161–172. doi: 10.3354/meps260161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin YH, Xu JL, Hu J, Wang LH, Ong SL, Leadbetter JR, Zhang LH. 2003. Acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Ralstonia strain XJ12B represents a novel and potent class of quorum-quenching enzymes. Mol Microbiol 47:849–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sio CF, Otten LG, Cool RH, Diggle SP, Braun PG, Bos R, Daykin M, Camara M, Williams P, Quax WJ. 2006. Quorum quenching by an N-acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Infect Immun 74:1673–1682. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1673-1682.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hentzer M, Riedel K, Rasmussen TB, Heydorn A, Andersen JB, Parsek MR, Rice SA, Eberl L, Molin S, Hoiby N, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M. 2002. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria by a halogenated furanone compound. Microbiology 148:87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hjelmgaard T, Persson T, Rasmussen TB, Givskov M, Nielsen J. 2003. Synthesis of furanone-based natural product analogues with quorum sensing antagonist activity. Bioorg Med Chem 11:3261–3271. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(03)00295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boukraa M, Sabbah M, Soulere L, El Efrit ML, Queneau Y, Doutheau A. 2011. AHL-dependent quorum sensing inhibition: synthesis and biological evaluation of alpha-(N-alkyl-carboxamide)-gamma-butyrolactones and alpha-(N-alkyl-sulfonamide)-gamma-butyrolactones. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21:6876–6879. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabbah M, Soulere L, Reverchon S, Queneau Y, Doutheau A. 2011. LuxR dependent quorum sensing inhibition by N,N′-disubstituted imidazolium salts. Bioorg Med Chem 19:4868–4875. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgkinson JT, Galloway WR, Wright M, Mati IK, Nicholson RL, Welch M, Spring DR. 2012. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of non-natural modulators of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Org Biomol Chem 10:6032–6044. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soni KA, Jesudhasan P, Cepeda M, Widmer K, Jayaprakasha GK, Patil BS, Hume ME, Pillai SD. 2008. Identification of ground beef-derived fatty acid inhibitors of autoinducer-2-based cell signaling. J Food Prot 71:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alfaro JF, Zhang T, Wynn DP, Karschner EL, Zhou ZS. 2004. Synthesis of LuxS inhibitors targeting bacterial cell-cell communication. Org Lett 6:3043–3046. doi: 10.1021/ol049182i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowery CA, McKenzie KM, Qi L, Meijler MM, Janda KD. 2005. Quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi: probing the specificity of the LuxP binding site. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 15:2395–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semmelhack MF, Campagna SR, Hwa C, Federle MJ, Bassler BL. 2004. Boron binding with the quorum sensing signal AI-2 and analogues. Org Lett 6:2635–2637. doi: 10.1021/ol048976u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roy V, Fernandes R, Tsao CY, Bentley WE. 2010. Cross species quorum quenching using a native AI-2 processing enzyme. ACS Chem Biol 5:223–232. doi: 10.1021/cb9002738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganin H, Tang X, Meijler MM. 2009. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing by AI-2 analogs. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 19:3941–3944. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xavier KB, Miller ST, Lu W, Kim JH, Rabinowitz J, Pelczer I, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. 2007. Phosphorylation and processing of the quorum-sensing molecule autoinducer-2 in enteric bacteria. ACS Chem Biol 2:128–136. doi: 10.1021/cb600444h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rasmussen TB, Bjarnsholt T, Skindersoe ME, Hentzer M, Kristoffersen P, Kote M, Nielsen J, Eberl L, Givskov M. 2005. Screening for quorum-sensing inhibitors (QSI) by use of a novel genetic system, the QSI selector. J Bacteriol 187:1799–1814. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1799-1814.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inoue H, Nojima H, Okayama H. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerlach GF, Allen BL, Clegg S. 1988. Molecular characterization of the type 3 (MR/K) fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 170:3547–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mårdén P, Tunlid A, Malmcrona-Friberg K, Odham G, Kjelleberg S. 1985. Physiological and morphological changes during short term starvation of marine bacterial islates. Arch Microbiol 142:326–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00491898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lane DJ. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p 115–175. In Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M (ed), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiland N, Loscher C, Metzger R, Schmitz R. 2010. Construction and screening of marine metagenomic libraries. Methods Mol Biol 668:51–65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-823-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Egland KA, Greenberg EP. 1999. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: elements of the luxl promoter. Mol Microbiol 31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hagen SJ, Son M, Weiss JT, Young JH. 2010. Bacterium in a box: sensing of quorum and environment by the LuxI/LuxR gene regulatory circuit. J Biol Phys 36:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s10867-010-9186-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mack DR, Blain-Nelson PL. 1995. Disparate in vitro inhibition of adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli RDEC-1 by mucins isolated from various regions of the intestinal tract. Pediatr Res 37:75–80. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199501000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Djordjevic D, Wiedmann M, McLandsborough LA. 2002. Microtiter plate assay for assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:2950–2958. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2950-2958.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karoui H, Bex F, Dreze P, Couturier M. 1983. Ham22, a mini-F mutation which is lethal to host cell and promotes recA-dependent induction of lambdoid prophage. EMBO J 2:1863–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogura T, Hiraga S. 1983. Mini-F plasmid genes that couple host cell division to plasmid proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80:4784–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miki T, Chang ZT, Horiuchi T. 1984. Control of cell division by sex factor F in Escherichia coli. II. Identification of genes for inhibitor protein and trigger protein on the 42.84–43.6 F segment. J Mol Biol 174:627–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blattner FR, Plunkett G III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Surette MG, Bassler BL. 1999. Regulation of autoinducer production in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 31:585–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taga ME, Semmelhack JL, Bassler BL. 2001. The LuxS-dependent autoinducer AI-2 controls the expression of an ABC transporter that functions in AI-2 uptake in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 42:777–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuo A, Blough NV, Dunlap PV. 1994. Multiple N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone autoinducers of luminescence in the marine symbiotic bacterium Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 176:7558–7565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tubiash HS, Colwell RR, Sakazaki R. 1970. Marine vibrios associated with bacillary necrosis, a disease of larval and juvenile bivalve mollusks. J Bacteriol 103:271–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qian PY, Lau SC, Dahms HU, Dobretsov S, Harder T. 2007. Marine biofilms as mediators of colonization by marine macroorganisms: implications for antifouling and aquaculture. Mar Biotechnol 9:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10126-007-9001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fuqua WC, Winans SC. 1994. A LuxR-LuxI type regulatory system activates Agrobacterium Ti plasmid conjugal transfer in the presence of a plant tumor metabolite. J Bacteriol 176:2796–2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dobretsov S, Teplitski M, Paul V. 2009. Mini-review: quorum sensing in the marine environment and its relationship to biofouling. Biofouling 25:413–427. doi: 10.1080/08927010902853516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez Barrios AF, Zuo R, Hashimoto Y, Yang L, Bentley WE, Wood TK. 2006. Autoinducer 2 controls biofilm formation in Escherichia coli through a novel motility quorum-sensing regulator (MqsR, B3022). J Bacteriol 188:305–316. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.305-316.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beloin C, Roux A, Ghigo JM. 2008. Escherichia coli biofilms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 322:249–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Balestrino D, Haagensen JA, Rich C, Forestier C. 2005. Characterization of type 2 quorum sensing in Klebsiella pneumoniae and relationship with biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 187:2870–2880. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.8.2870-2880.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di Martino P, Fursy R, Bret L, Sundararaju B, Phillips RS. 2003. Indole can act as an extracellular signal to regulate biofilm formation of Escherichia coli and other indole-producing bacteria. Can J Microbiol 49:443–449. doi: 10.1139/w03-056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sauer K, Camper AK, Ehrlich GD, Costerton JW, Davies DG. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J Bacteriol 184:1140–1154. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1140-1154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP. 1998. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de Kievit TR, Iglewski BH. 2000. Bacterial quorum sensing in pathogenic relationships. Infect Immun 68:4839–4849. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.9.4839-4849.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lombardia E, Rovetto AJ, Arabolaza AL, Grau RR. 2006. A LuxS-dependent cell-to-cell language regulates social behavior and development in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 188:4442–4452. doi: 10.1128/JB.00165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ren D, Sims JJ, Wood TK. 2002. Inhibition of biofilm formation and swarming of Bacillus subtilis by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Lett Appl Microbiol 34:293–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yarwood JM, Bartels DJ, Volper EM, Greenberg EP. 2004. Quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Bacteriol 186:1838–1850. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.6.1838-1850.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Persson T, Hansen TH, Rasmussen TB, Skinderso ME, Givskov M, Nielsen J. 2005. Rational design and synthesis of new quorum-sensing inhibitors derived from acylated homoserine lactones and natural products from garlic. Org Biomol Chem 3:253–262. doi: 10.1039/b415761c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McClean KH, Winson MK, Fish L, Taylor A, Chhabra SR, Camara M, Daykin M, Lamb JH, Swift S, Bycroft BW, Stewart GS, Williams P. 1997. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology 143:3703–3711. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adonizio AL, Downum K, Bennett BC, Mathee K. 2006. Anti-quorum sensing activity of medicinal plants in southern Florida. J Ethnopharmacol 105:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cao JG, Meighen EA. 1993. Biosynthesis and stereochemistry of the autoinducer controlling luminescence in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol 175:3856–3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang K, Zhang Y, Yu M, Shi X, Coenye T, Bossier P, Zhang XH. 2013. Evaluation of a new high-throughput method for identifying quorum quenching bacteria. Sci Rep 3:2935. doi: 10.1038/srep02935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Patel P, Callow ME, Joint I, Callow JA. 2003. Specificity in the settlement-modifying response of bacterial biofilms towards zoospores of the marine alga Enteromorpha. Environ Microbiol 5:338–349. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee OO, Qian PY. 2003. Chemical control of bacterial epibiosis and larval settlement of Hydroides elegans in the red sponge Mycale adherens. Biofouling 19(Suppl):171–180. doi: 10.1080/0892701021000055000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holmstrom C, Kjelleberg S. 1999. Marine Pseudoalteromonas species are associated with higher organisms and produce biologically active extracellular agents. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 30:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dang H, Lovell CR. 2000. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:467–475. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.2.467-475.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Klein GL, Soum-Soutera E, Guede Z, Bazire A, Compere C, Dufour A. 2011. The anti-biofilm activity secreted by a marine Pseudoalteromonas strain. Biofouling 27:931–940. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2011.611878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harder T. 2008. Marine epibiosis: concepts, ecological consequences and host defence, p 219–232. In Flemming H-C, Venkatesan R, Murthy SP, Cooksey K (ed), Marine and industrial biofouling, vol 4 Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Armstrong E, Yan L, Boyd KG, Wright PC, Burgess JG. 2001. The symbiotic role of marine microbes on living surfaces. Hydrobiologia 461:37–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1012756913566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Boyd KG, Adams DR, Burgess JG. 1999. Antibacterial and repellent activities of marine bacteria associated with algal surfaces. Biofouling 14:227–236. doi: 10.1080/08927019909378414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bandyopadhyay D, Prashar D, Luk YY. 2011. Anti-fouling chemistry of chiral monolayers: enhancing biofilm resistance on racemic surface. Langmuir 27:6124–6131. doi: 10.1021/la200230t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davis AR, Targett NM, McConnell OJ, Young CM. 1989. Epibiosis of marine algae and benthic invertebrates: natural products chemistry and other mechanisms inhibiting settlement and overgrowth. Bioorg Marine Chem 3:85–114. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Strelkova EA, Zhurina MV, Plakunov VK, Beliaev SS. 2012. Antibiotics stimulation of biofilm formation. Mikrobiologiia 81:282–285. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Nys R, Givskov M, Kumar N, Kjelleberg S, Steinberg PD. 2006. Furanones. Prog Mol Subcell Biol 42:55–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]