Abstract

Although a group of people working together remembers more than any one individual, they recall less than their predicted potential. This finding is known as collaborative inhibition, and is generally thought to arise due to retrieval disruption. However, there is growing evidence that is inconsistent with the retrieval disruption account, suggesting that additional mechanisms also contribute to collaborative inhibition. In the current studies, we examined two alternate mechanisms -- retrieval inhibition and retrieval blocking. To identify the contributions of retrieval disruption, retrieval inhibition, and retrieval blocking we tested how collaborative recall of entirely unshared information influences subsequent individual recall and individual recognition memory. If collaborative inhibition is due solely to retrieval disruption, then there should be a release from the negative effects of collaboration on subsequent individual recall and recognition tests. If it is due to retrieval inhibition, then the negative effects of collaboration should persist on both individual recall and recognition memory tests. Finally, if it is due to retrieval blocking, then the impairment should persist on subsequent individual free recall, but not recognition, tests. Novel to the current study, results suggest that retrieval inhibition plays a role in the collaborative inhibition effect. The negative effects of collaboration persisted on a subsequent, always-individual, free recall test (Experiment 1) and also on a subsequent, always-individual, recognition test (Experiment 2). However, consistent with the retrieval disruption account, this deficit was attenuated (Experiment 1). Together, these results suggest that, in addition to retrieval disruption, multiple mechanisms play a role in collaborative inhibition.

Keywords: collaborative inhibition, retrieval disruption, retrieval inhibition, retrieval blocking, part-set cuing

When it comes to memory, it is not surprising that the old adage ‘two heads are better than one’ is true. A group of individuals working together remembers more than a single individual working alone (e.g., Perlmutter & de Montmollin, 1952). However, research also shows that collaboration is not always beneficial for memory. A group of individuals working together (i.e., a collaborative group) remembers less than their potential, measured as the non-redundant sum of the same number of individuals working alone (i.e., a nominal group). This outcome is known as collaborative inhibition (Weldon & Bellinger, 1997). Thus, while two heads are better than one, two heads apart are better than two heads together.

Intuition suggests that collaborative inhibition could be due to a lack of motivation when working in a group (compared to individual) setting; however, this is not the case (Weldon, Blair, & Huebsch, 2000). Rather, collaborative inhibition is typically thought to arise because of retrieval disruption (B.H. Basden, Basden, Bryner, & Thomas, 1997). When an individual learns information, such as a word list, she organizes it into memory in an idiosyncratic manner. Later, her ability to remember this information will be optimized if she can use her idiosyncratic organizational structure to guide her retrieval. Problematically, during collaborative recall this is not entirely possible; here she will be exposed to the recall of her group members, who are similarly attempting to recall the information according to their own organizational strategies. Because no two individuals will organize information identically, the recall of her group members will not be aligned to her strategy and will therefore force her to recall in a non-optimal manner. Similarly, her recall will be misaligned to her group members’ strategies and force them to recall in non-optimal manners. Together, this results in each individual recalling less in a group versus an individual setting.

Although a large body of research supports the retrieval disruption account of collaborative inhibition, there is growing evidence that it may not be the sole mechanism underlying collaborative inhibition. Specifically, three key pieces of evidence in favor of the retrieval disruption account have not been replicated in recent research.

First, according to the retrieval disruption account, collaborative inhibition should be attenuated when encoding strategies are aligned, rather than misaligned, across group members. This is because aligned encoding strategies should later lead to less retrieval disruption, and hence less collaborative inhibition. Although some research has supported this conclusion (Barber, Rajaram, & Fox, 2012; Finlay, Hitch, & Meudell, 2000; Garcia-Marques, Garrido, Hamilton, & Ferreira, 2011; Harris, Barnier, & Sutton, 2013), other research has failed to replicate this effect; in some studies collaborative inhibition does not vary as a function of whether the study information was aligned or misaligned across group members (Barber & Rajaram, 2011; Dahlstrom, Danielsson, Emilsson, & Andersson, 2011).

Second, according to the retrieval disruption account, collaborative inhibition should be attenuated when people attempt to recall non-overlapping, rather than overlapping, sets of items. This is because hearing another person recalling irrelevant, rather than relevant, items should be less disruptive to an individuals’ organizational strategy. An early study supported this conclusion (B.H. Basden, et al., 1997; Experiment 3). However, a recent study failed to replicate this effect. Here, some items were studied by all group members but other items were studied by only a single group member. Counter to the retrieval disruption account, collaborative inhibition was actually greatest for the unshared items (Meade & Gigone, 2011, Experiment 1).

As a final example, according to the retrieval disruption account, collaborative inhibition should be eliminated when the test format does not rely on one’s own organizational strategies, such as a recognition or cued recall test. This is because these test formats are disruptive to organizational strategies both when people are recalling collaboratively and individually, hence eliminating the disparity between the conditions in the extent to which they experience retrieval disruption. Again, although early research supported this conclusion (e.g., Barber, Rajaram, & Aron, 2010; Thorley & Dewhurst, 2009; Finlay, et al., 2000), this has not always been replicated. Collaborative inhibition has now been reported in recognition (Danielsson, Dahlstrom, & Andersson, 2011) and in cued recall tests (Kelley, Reysen, Ahlstrand, & Pentz, 2012; Meade & Roediger, 2009).

The fact that collaborative inhibition robustly occurs even in situations where the retrieval disruption account would not predict leads to the question of whether multiple mechanisms underlie collaborative inhibition. The present experiments test this question by drawing on similarities between the collaborative inhibition effect and the part-set cuing effect. Put simply, part-set cuing refers to the fact that providing people with retrieval cues (in the form of a partial set of studied items) lowers recall for the remaining items compared to a condition in which no cues were provided (Slamecka, 1968; for a review see Nickerson, 1984). The similarity between this and collaborative inhibition is readily apparent. In both cases, some previously studied items are provided by other sources (the items on the recall sheet in a part-set cuing paradigm and the items recalled by group members in a collaborative memory paradigm), and this leads to memory impairments.

Of current interest, multiple mechanisms are thought to underlie part-set cuing (see Nickerson, 1984), and hence might also play a role in collaborative inhibition. Here, we focus on three mechanisms. First, some have argued that part-set cuing arises due to retrieval disruption (i.e., the mechanism previously discussed with regards to collaborative inhibition). Here the cue words (provided by the experimenter) are thought to disrupt the individual’s organizational strategy, forcing her to recall in a non-optimal manner and lower the likelihood that she will retrieve the non-cued words (e.g., D.R. Basden & Basden, 1995). In contrast, others have argued that part-set cuing arises due to retrieval inhibition. Here, strengthening the cue words is thought to inhibit memories for the non-cued words by suppressing their memory representations, making them unavailable to be retrieved (e.g., Anderson, Bjork, & Bjork, 1994; Bäuml & Aslan, 2004). Finally, others have argued that part-set cuing arises due to retrieval blocking. Here, the cue words are thought to become stronger candidates for retrieval than the non-cued words. Because of this, during the part-set cued test people continually bring to mind the strengthened cue words, which blocks access to the non-cued words (e.g., Rundus, 1973).1

In the part-set cuing paradigm, these three accounts differ in their predictions about what happens on subsequent memory tests. After completing the first memory test (either without cues in the free recall condition or with cues – a partial set of studied words - in the part-set cuing condition), all participants are given a second memory test (without cues). This second test is sometimes a free recall test and other times a recognition test. According to the retrieval disruption account, the cue words provided earlier temporarily disrupted the individual’s idiosyncratic retrieval scheme, however, there should be a release from disruption when the cues are removed and she can resume using her organizational scheme. Because of this no differences should exist on this second test as a function of whether participants previously took a free recall or a part-set cue recall test (e.g., D.R. Basden & Basden, 1995).

In contrast, according to the retrieval inhibition account the cue words provided earlier have led to long-term suppression of the non-cued words’ memory representations. Because of this there should be lasting detriments with the part-set cue recall group continuing to underperform compared to the free-recall group. Furthermore, because the non-cued words representations have been rendered unavailable, this impairment should persist no matter how memory for the non-cued words is probed. That is, the impairment should persist for both free recall and recognition tests (e.g., Aslan, Bäuml, & Grundgeiger, 2007; Bäuml & Aslan, 2006).

Finally, according to the retrieval blocking account, the representations of the cue words were strengthened when they were previously presented. These strengthened cued words then persistently come to mind and block spontaneous access to the weaker representations of the non-cued words. Critically, although the retrieval blocking account posits that access to the non-cued words is blocked, it also posits that the non-cued words are still available (e.g., Rundus, 1973). Thus, the part-set cuing decrements should continue to be present when the memory search is self-guided, as in free recall, but there should be a release from this decrement when the search to them is externally guided, as in recognition.

We tested the contribution of these three mechanisms to the collaborative inhibition effect by examining how collaboration affects subsequent individual memory performance.2 Many studies have shown down-stream benefits of collaborative recall; individuals who were previously members of collaborative groups typically have superior subsequent individual memory than individuals who were previously members of nominal groups (e.g., Blumen & Rajaram, 2008; Harris, et al., 2012; Rajaram & Pereira-Pasarin, 2007; Weldon & Bellinger, 1997). This benefit occurs for two reasons. First, during collaboration individuals are re-exposed to forgotten items that their group members successfully recalled. Thus, collaborative recall serves as a relearning opportunity and increases subsequent individual memory.

Second, because collaborative inhibition has been thought to arise from retrieval disruption, there is assumed to be a release from the disruptive effects of collaboration once individuals are again able to use their idiosyncratic organizational strategies. Although this release is assumed to occur, some evidence suggests it is incomplete. Within post-collaborative individual recall people persistently forget to include items that they themselves contributed to the earlier collaborative discussion (Congleton & Rajaram, 2011; also Blumen & Rajaram, 2008). Furthermore, this forgetting increases as the magnitude of collaborative inhibition increases (Congleton & Rajaram, 2011), suggesting that collaborative inhibition exerts lasting negative impacts on recall (and that retrieval disruption is not the sole mechanism underlying collaborative inhibition). However, none of these previous studies have used a recognition test in the post-collaborative individual memory stage, and thus cannot disentangle whether the continued negative effects arising from collaboration are due to retrieval blocking or retrieval inhibition.

In previous studies it has also been difficult to directly examine whether a release from collaborative inhibition occurs because individuals are re-exposed to forgotten items that their group members successfully recalled during collaboration. These re-exposure benefits could off-set any persistent negative effects of collaboration. To circumvent this problem, in these experiments each individual studied a separate list of unrelated words.3 Thus, during the collaborative recall session re-exposure benefits did not occur, which allowed us to examine whether there was a release from collaborative inhibition, and hence identify the mechanisms underlying collaborative inhibition.

In brief, groups of participants studied non-redundant sets of words. Later, some participants collaboratively recalled these words while others worked individually. All participants next completed a second, always-individual, memory test. In Experiment 1 this was a free recall test, in Experiment 2 this was a recognition test. If collaborative inhibition is solely due to retrieval disruption then the negative effects of collaboration should be absent on both the free recall test and on the recognition test. If it is due to retrieval inhibition, then the impairment should persist on both the free recall and recognition tests. Finally, if it is due to retrieval blocking, then the impairment should persist on the free recall test but be eliminated on the recognition test.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

A total of 108 Stony Brook University undergraduates participated for course credit. Of these, 54 participants (18 triads of strangers) were assigned to the collaborative group condition and 54 to the nominal group condition.

Materials

We generated 162 unrelated nouns from the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Wilson, 1988). Words were 5–8 letters in length, 25–74 per million in frequency, and 400–635 in concreteness. These words were separated into three 54-word lists that were approximately matched on these characteristics. Within each list, we designated two words as primacy buffers, two as recency buffers, and 50 as critical items. Each list had a low degree of inter-item associations, which should increase the likelihood of observing retrieval inhibition (Bäuml & Aslan, 2006) if it plays a role.

Procedure

Encoding

Participants sat at separate computers and individually studied one of the lists in preparation for a memory test. Words appeared one at a time, centered on the screen, for 5 seconds. Within each group (collaborative or nominal), each group member saw a different list.

Filled Delay

Participants completed puzzles for 10 minutes.

Group (Nominal or Collaborative) Memory Test

Participants next completed a free recall test for 7 minutes in which they wrote down as many of the studied words as possible in any order. In the nominal groups participants worked individually. In the collaborative groups participants worked in triads. No specific instructions were provided about how to resolve disputes. In each group, only one participant served as the scribe. Participants were told they may or may not have studied the same words, but that either way they needed to work together to recall them.4

Final Individual Memory Test

Immediately following the group test, all participants completed a second free recall test for 7 minutes. Regardless of condition, participants worked individually and were instructed to only write down words they remembered from their own study list.

Results

An α = .05 significance level was used for all analyses in both Experiments.

Collaborative Inhibition

Group recall was the proportion of the 150 critical words (50 studied by each individual) recalled by the collaborative group or by the three nominal group members working alone. There were no redundancies to remove in the nominal group calculation because there were no redundancies in the studied items.

Collaborative inhibition was observed (Table 1). Nominal groups (.23) had higher recall than collaborative groups (.17), t(34) = 3.30, d = 1.13. Furthermore, nominal groups (.20) had higher recall than collaborative groups (.15) even when examining ‘corrected recall’ (i.e., the number of items correctly recalled minus the number of intrusions divided by the total number of items), t(34) = 2.24, d = .75.5

Table 1.

Memory performance in Experiment 1 on both the group (collaborative or nominal) recall test and on the final, always-individual, recall test. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. During the group recall test, errors were defined as items not studied by any of the group members. During the subsequent, always-individual, recall test errors were defined as items not studied by the participant herself. One collaborative group participant, whose intrusion rate on the final recall test was more than 5 standard deviations above the mean, was excluded from that calculation. For the Test 2 group performance, we calculated nominal group performance both for individuals that were previously members of collaborative groups and also for individuals that were previously members of nominal groups.

| Test 1: Group (collaborative or nominal) recall test |

Test 2: Final individual recall test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal group members |

Collaborative group members |

Nominal group members |

Collaborative group members |

|

| Proportion correctly recalled by each individual group member | .25 (.13) | .18 (.11) | .25 (.14) | .20 (.12) |

| Proportion correctly recalled by the group as a whole | .234 (.07) | .166 (.05) | .235 (.08) | .181 (.06) |

| Number of intrusions (by the group as a whole on test 1 and by individuals on test 2) | 5.67 (3.58) | 2.83 (1.76) | 1.93 (2.26) | 2.81 (4.10) |

| Corrected recall (by the group as a whole on test 1 and by individuals on test 2) | .20 (.08) | .15 (.05) | .24 (.16) | .16 (.18) |

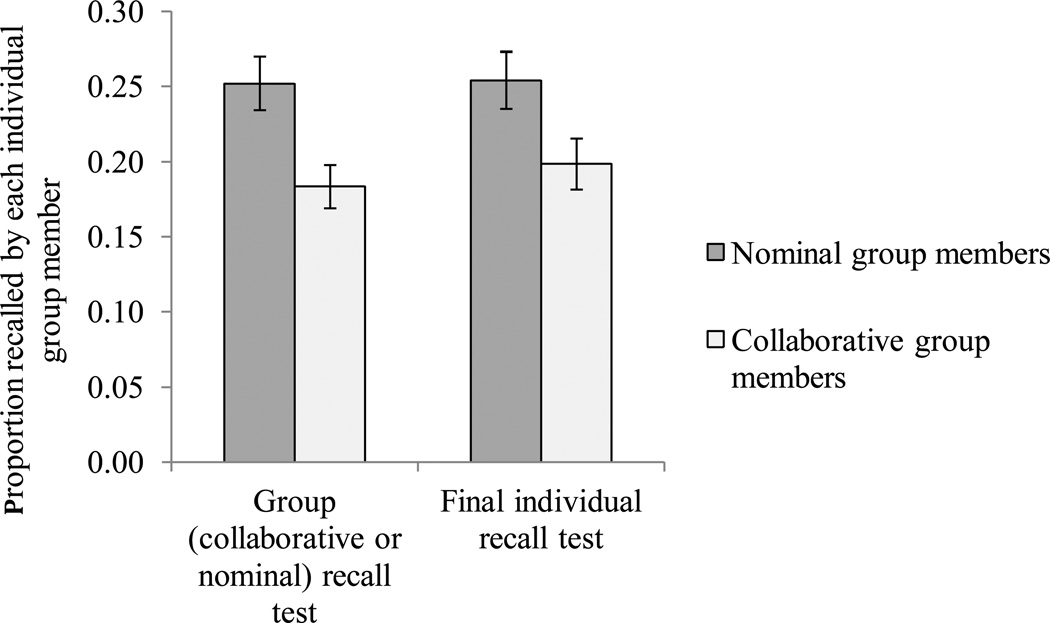

Since each group member studied a separate list of words there was no redundancy in the items recalled by any two individuals. Because of this, we also tested for collaborative inhibition using the individual, rather than the group, as the unit of analysis (i.e., the proportion of the 50 critical words recalled by each individual). Although complementary to the group analyses, this provides a clearer indication of how collaboration affects each individual’s ability to recall items. Results revealed that individuals recalled 28% less when in a group (.18) compared to individual (.25) setting, t(106) = 2.99, d = 0.58 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of items correctly recalled by each individual participant within both the group (collaborative or nominal) recall tests and also on the final, always-individual, recall test in Experiment 1. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

A ‘Release’ from Collaborative Inhibition?

Did the memory deficits associated with collaborative recall persist on a subsequent, always-individual, recall test? Results indicated that they did. Individuals who previously recalled in a nominal group (.25) recalled a greater proportion of their studied lists (i.e., the 50 critical words) than individual who previously recalled in a collaborative group (.20), t(106) = 2.18, d = .42 (Figure 1).

Although the negative consequences of collaborative recall persisted, further analyses revealed that this deficit was attenuated on the second, always-individual, recall test. We conducted a 2 (Group type: Nominal vs. Collaborative) × 2 (Test: Initial group test vs. Final individual test) ANOVA on group recall, and used nominal group recall levels at Test 2 as well, to equate the units of analyses. Here, there was a significant interaction between group type and test, F(1, 34) = 4.70, MSE < .001, ηp2 = .12. Whereas recall of nominal group members did not differ between the initial and final recall tests, F(1, 17) = 0.03, recall of the collaborative group members was higher on the final test than on the initial test, F(1, 17) = 9.36, MSE < .001, ηp2 = .36 (Table 1). This suggests a partial release from collaborative inhibition and is consistent with the retrieval disruption mechanism. Given that there was no opportunity to be re-exposed to forgotten items in this paradigm, this is the first clear demonstration that collaborative inhibition is partially eliminated when individuals are once again able to use their own idiosyncratic retrieval strategies.

Discussion

Novel to this study, we observed collaborative inhibition for completely unshared study information. Furthermore, although this deficit was attenuated it nevertheless persisted on a second, always-individual, free recall test. Continued memory deficits associated with collaborative recall cannot be readily explained by the retrieval disruption account. An explicit assumption of the retrieval disruption account is that the negative effects of collaboration should no longer persist once the source of the disruption (i.e., the other individuals) is removed (e.g. D.R. Basden & Basden, 1995). Although the finding of attenuated collaborative inhibition is in line with the retrieval disruption account, the continued persistence of collaborative inhibition contradicts this theory, but instead is in line with both the retrieval inhibition and retrieval blocking accounts.

Experiment 2

To distinguish between the retrieval inhibition and retrieval blocking accounts, in Experiment 2 we replaced the final always-individual, free-recall test with a recognition test. According to the retrieval inhibition account, the memory representations for the non-recalled items were suppressed during collaborative recall, rendering them less available to be subsequently recalled or recognized. Thus, collaborative group members should subsequently be less able than nominal group members to discriminate old from new items. In contrast, according to the blocking account, the items recalled during the collaborative memory session were strengthened. They then persistently come to mind during free recall tests, blocking accessibility to weaker memory traces. Importantly, these blocking effects should be eliminated when items are tested utilizing independent cues since the blocking account posits that only accessibility but not availability of the memory traces has been affected. Thus, whereas the retrieval inhibition account posits continued collaborative deficits on a subsequent recognition test, the blocking account does not.

Method

Participants

A new sample of 108 Stony Brook University undergraduates participated for course credit or payment. Of these, 54 participants (18 triads of strangers) were assigned to the collaborative group condition, and 54 to the nominal group condition.

Materials

In addition to the three lists from Experiment 1, we generated a fourth list of 54 words using the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Wilson, 1988) with characteristics that matched those from the previous lists. Across groups the four lists were counterbalanced; each list had an equal probability of appearing during the study phase and an equal probability of appearing during the recognition memory test as a non-studied lure.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1 with three exceptions. First, as in Experiment 1, each group member was exposed to a different list at encoding. However, here, it was either List 1, 2, 3, or 4. Second, during the collaborative recall test no explicit mention was made that the study lists may have been unshared.6 Finally, in this experiment the final individual memory test consisted of a self-paced, paper and pencil, recognition test. Regardless of condition, participants completed this recognition test individually. For each group the non-studied lures were the 54 items from the list not studied by any group member. For example, assume an individual studied List 1 and her group members studied Lists 3 and 4, respectively. For this individual, the final recognition test would contain the items from Lists 1 and 2. For her group members, the final recognitions tests would contain the items from Lists 3 and 2, or the items from Lists 4 and 2, respectively.

Results

Collaborative Inhibition

Collaborative inhibition for unshared information was again observed. Collaborative groups (.14) recalled significantly less than nominal groups (.19), t(34) = 2.89, d = .99 (Table 2). Similarly, individuals recalled 26% less in a collaborative setting (.14) than in an individual setting (.19), t (106) = 2.46, d = .48 (see Table 2). Furthermore, collaborative groups (.13) recalled less than nominal groups (.17) even when examining ‘corrected recall’ (i.e., the number of items correctly recalled minus the number of intrusions divided by the total number of items), t(34) = 1.68, p = .05 (one-tailed), d = .56 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Memory performance in Experiment 2 on both the group (collaborative or nominal) recall test and on the final, always-individual, recognition test. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

| Test 1: Group (collaborative or nominal) recall test |

Test 2: Final individual recognition test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal group members |

Collaborative group members |

Nominal group members (previously) |

Collaborative group members (previously) |

|

| Proportion correctly recalled by the group as a whole | .19 (.06) | .14 (.04) | ||

| Number of intrusions by the group as a whole | 6.22 (4.68) | 3.44 (2.81) | ||

| Corrected recall | .17 (.07) | .13 (.04) | ||

| A’ (discriminability) | .85 (.07) | .81 (.09) | ||

| B”D (response bias) | .53 (.41) | .44 (.42) | ||

| Hit rate | .66 (.14) | .64 (.13) | ||

| False alarm rate | .13 (.11) | .18 (.13) | ||

| Corrected recognition (hits minus false alarms) | .52 (.17) | .46 (.18) | ||

A ‘Release’ from Collaborative Inhibition?

Did collaborative recall continued to exert negative effects on the subsequent individual recognition test?7 To answer this we examined discriminability, which is the ability to distinguish old from new items. Because some participants made no false alarms we used A’, a non-parametric discriminability measure (see Snodgrass, Levy-Berger, & Haydon, 1985). A’ scores can range from 0 to 1, with 0.5 indicating chance performance. Results showed that the negative effects of collaboration persisted. Individuals who previously recalled in a collaborative group had lower discriminability scores (.81) than individuals who previously recalled in a nominal group (.85), t(105) = 2.23, d = .43 (Table 2). A similar pattern occurred in corrected recognition (previously in collaborative group = .46, previously in nominal group = .52), but just failed to reach statistical significance, t(105) = 1.90, p = .06, d = .37.

The two groups were conservative and did not differ in response bias, which is their tendency to respond ‘old’ or ‘new’ (using B’’D; see Donaldson, 1992); previously in collaborative group = .44, previously in nominal group = .53, t(105) = 1.16, p = .28, d = .21.

Discussion

We again observed collaborative inhibition of unshared study information. Furthermore, this deficit persisted on a subsequent individual recognition test, indicating a role of inhibition, rather than blocking, in collaborative inhibition.

General Discussion

Across two experiments, we tested three potential causes of collaborative inhibition. We did this by examining whether collaborative memory deficits persist on subsequent individual recall and recognition memory tests. If collaborative inhibition is due to retrieval disruption, then its detrimental effects should be limited to the group memory test, and should be absent on subsequent individual memory tests. In contrast, if collaborative inhibition is due to retrieval inhibition then its detrimental effects should persist on subsequent individual memory tests regardless of their format. Finally, if collaborative inhibition is due to retrieval blocking, then its detrimental effects should persist on subsequent self-guided individual memory tests, such as free recall, but be absent on subsequent externally-guided individual memory tests, such as recognition.

Novel to the current research we observed evidence in favor of retrieval inhibition. Consistent with the retrieval inhibition account, collaborative recall was associated with continued memory deficits both on a subsequent individual free recall test (Experiment 1) and on a subsequent individual recognition test (Experiment 2). However, although collaborative inhibition persisted on a subsequent individual free recall test, it was attenuated (Experiment 1). This attenuation is consistent with the retrieval disruption account, which is the only mechanism to predict release from the disruptive effects of collaboration during free recall. Thus, collaborative inhibition may have multiple bases - in addition to retrieval disruption, retrieval inhibition also plays a role.

The current results are the first explicit demonstration that retrieval inhibition plays a role in collaborative inhibition. These results converge with evidence from the socially shared retrieval-induced forgetting paradigm (Cuc, Koppel, & Hirst, 2009), which has reported slower reaction times (indicative of retrieval inhibition) in post-conversational recall and recognition (Coman, Manier, & Hirst, 2009). However, our study is the first to provide evidence for retrieval inhibition underlying collaborative memory deficits using the measure of lower discriminability.

Although we observed a primary role for retrieval inhibition in the current paradigm, future research is needed to delineate when each of collaborative inhibition’s mechanisms most strongly contributes to the effect. For example, part-set cuing is caused by retrieval disruption when the encoded items have a high degree of inter-item associations but by retrieval inhibition when the items have a low degree of inter-item associations (Bäuml & Aslan, 2006). Based on this, in the current studies we used items with a low degree of inter-item associations to increase the likelihood of detecting retrieval inhibition. With a higher degree of inter-item associations, the contributions of retrieval inhibition and retrieval disruption may reverse. With a higher degree of inter-item associations, and a hierarchical organizational structure, retrieval blocking likely plays a larger role as well (see Rundus, 1973). The role of retrieval disruption may also be greater when the studied information is shared, rather than unshared, amongst the group members. Hearing unshared information during collaboration may disrupt one’s own retrieval strategies to some extent by prompting discussion, or by eliciting cross-cuing (based on the idiosyncratic associations between that unshared information and the studied information). However, this disruption should theoretically be lower than what is caused by hearing a group member recall shared information.

Although the use of unshared study information allowed us to directly examine collaborative inhibitions’ underlying mechanisms one may wonder what groups were doing when ‘collaborating’ to recall unshared information. The limited conversational data available to us clearly indicates that group members actively collaborated. Not only was this a requirement since only one participant served as a scribe, but participants occasionally still asked for confirmations (“does this sound familiar?”), or incorrectly confirmed (“oh yeah, I think I had ‘soldier’ too”), that items had been shared. There are also real-world situations in which people recall unshared information: adults may reminisce together about unshared childhood memories, co-workers may collaboratively discuss the events of their weekends, and scientists may discuss their non-overlapping areas of research expertise.

In sum, collaborative inhibition is generally thought to be due to retrieval disruption. However, these studies suggest that multiple factors, including retrieval inhibition, together lead to collaborative inhibition.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Stony Brook University students Bavani Paneerselvam, Juliana Tseng, and Kayla Young for research assistance. Celia Harris participated in this research project as a visiting doctoral scholar in Suparna Rajaram’s laboratory at Stony Brook University. Writing of this manuscript was in part supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (T32-AG00037).

Footnotes

Note that retrieval blocking is different from production blocking, which is the idea that memory deficits occur because people must wait to produce their memory responses while listening to the cue words being provided. A previous study demonstrated that production blocking does not underlie collaborative inhibition (Wright & Klumpp, 2004).

The reduction in recall that occurs in collaborative groups compared to their potential has been defined as ‘collaborative inhibition’. Of note, this was meant as a descriptive term and not as a hypothesis about the effects’ underlying mechanism.

Meade and Gigone (2011) also used unshared study information. However, within this study each group studied both shared and unshared study information, and there was no final individual memory test. Thus, this previous study cannot address our study aims.

In both Experiment 1 and 2 the collaborative recall tests were audio recorded. However, due to a technical failure and experimenter error the majority of these recordings was incorrectly saved and is unavailable for analyses.

Intrusions were defined as items not studied by any of the group members.

In general, participants did not question the experimenter about whether or not the lists were shared or unshared. As in Experiment 1, they were also able to work together to collaboratively complete the recall test despite having studied different lists of words.

One collaborative group participant did not complete the entire recognition test and was eliminated from these analyses.

Contributor Information

Sarah J. Barber, Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California

Celia B. Harris, Department of Cognitive Science, Macquarie University

Suparna Rajaram, Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University.

References

- Anderson MC, Bjork RA, Bjork EL. Remembering can cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 1994;20:1063–1087. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.20.5.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A, Bäuml K-H, Grundgeiger T. The role of inhibitory processes in part-list cuing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33:335–341. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Rajaram S. Exploring the relationship between retrieval disruption from collaboration and recall. Memory. 2011;19:462–469. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.584389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Rajaram S, Aron A. When two is too many: Collaborative encoding impairs memory. Memory & Cognition. 2010;38:255–264. doi: 10.3758/MC.38.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Rajaram S, Fox EB. Learning and remembering with others: The key role of retrieval in shaping group recall and collective memory. Social Cognition. 2012;30:121–132. doi: 10.1521/soco.2012.30.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basden BH, Basden DR, Bryner S, Thomas RL., III A comparison of group and individual remembering: Does collaboration disrupt retrieval strategies? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1997;23:1176–1189. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basden BH, Basden DR, Henry S. Costs and benefits of collaborative remembering. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2000;14:497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Basden DR, Basden BH. Some tests of the strategy disruption interpretation of part-list cuing inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1995;21:1656–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Bäuml K-H, Aslan A. Part-list cuing as instructed retrieval inhibition. Memory & Cognition. 2004;32:610–617. doi: 10.3758/bf03195852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäuml K-H, Aslan A. Part-list cuing can be transient and lasting: The role of encoding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32:33–43. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumen HM, Rajaram S. Influence of re-exposure and retrieval disruption during group collaboration on later individual recall. Memory. 2008;16:231–244. doi: 10.1080/09658210701804495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman A, Manier D, Hirst W. Forgetting the unforgettable through conversation: Socially shared retrieval-induced forgetting of September 11 memories. Psychological Science. 2009;20:627–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congleton AR, Rajaram S. The influence of learning methods on collaboration: Prior repeated retrieval enhances retrieval organization, abolishes collaborative inhibition, and promotes post-collaborative memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2011;140:535–551. doi: 10.1037/a0024308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuc A, Koppel J, Hirst W. Silence is not golden: A case for socially shared retrieval-induced forgetting. Psychological Science. 2007;18:727–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström O, Danielsson H, Emilsson M, Andersson J. Does retrieval strategy disruption cause general and specific collaborative inhibition? Memory. 2011;19:140–154. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2010.539571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson H, Dahlström O, Andersson J. The more you remember the more you decide: Collaborative memory in adolescents with intellectual disability and their assistants. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson W. Measuring recognition memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1992;121:275–277. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.121.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay F, Hitch GJ, Meudell PR. Mutual inhibition in collaborative recall: Evidence for a retrieval-based account. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;26:1556–1567. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.6.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marques L, Garrido MV, Hamilton DL, Ferreira MB. Effects of correspondence between encoding and retrieval organization in social memory. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;48:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Harris CB, Barnier AJ, Sutton J. Consensus collaboration enhances group and individual recall accuracy. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2012;65:179–194. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2011.608590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CB, Barnier AJ, Sutton J. Shared encoding and the costs and benefits of collaborative recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2013;39:183–195. doi: 10.1037/a0028906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MR, Reysen MB, Ahlstrand KM, Pentz CJ. Collaborative inhibition persists following social processing. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2012;24:727–734. [Google Scholar]

- Meade ML, Gigone D. The effect of information distribution on collaborative inhibition. Memory. 2011;19:417–428. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.583928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson RS. Retrieval inhibition from part-set cuing: A persisting enigma in memory research. Memory & Cognition. 1984;12:531–552. doi: 10.3758/bf03213342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter H, De Montmollin G. Group learning of nonsense syllables. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1952;47:762–769. doi: 10.1037/h0059790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram S, Pereira-Pasarin LP. Collaboration can improve individual recognition memory: Evidence from immediate and delayed tests. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2007;14:95–100. doi: 10.3758/bf03194034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram S, Pereira-Pasarin LP. Collaborative memory: Cognitive research and theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:649–663. doi: 10.1177/1745691610388763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundus D. Analysis of rehearsal processes in free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1971;89:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Slamecka NJ. An examination of trace storage in free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1968;76:504–513. doi: 10.1037/h0025695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Levy-Berger G, Haydon M. Human experimental psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Thorley C, Dewhurst SA. False and veridical collaborative recognition. Memory. 2009;17:17–25. doi: 10.1080/09658210802484817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldon MS, Bellinger KD. Collective memory: Collaborative and individual processes in remembering. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1997;23:1160–1175. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldon MS, Blair C, Huebsch D. Group remembering: Does social loafing underlie collaborative inhibition? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;26:1568–1577. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.6.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. MRC Psycholinguistic database: Machine-usable dictionary, Version 2.00. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 1988;20:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wright DB, Klumpp A. Collaborative inhibition is due to the product, not the process, of recalling in groups. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11:1080–1083. doi: 10.3758/bf03196740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]