Abstract

This article confronts a persistent challenge in research on children’s geographies and politics: the difficulty of recognizing forms of political agency and practice that by definition fall outside of existing political theory. Children are effectively “always already” positioned outside most of the structures and ideals of modernist democratic theory, such as the public sphere and abstracted notions of communicative action or “rational” speech. Recent emphases on embodied tactics of everyday life have offered important ways to recognize children’s political agency and practice. However, we argue here that a focus on spatial practices and critical knowledge alone cannot capture the full range of children’s politics, and show how representational and dialogic practices remain a critical element of their politics in everyday life. Drawing on de Certeau’s notion of spatial stories, and Bakhtin’s concept of dialogic relations, we argue that children’s representations and dialogues comprise a significant space of their political agency and formation, in which they can make and negotiate social meanings, subjectivities, and relationships. We develop these arguments with evidence from an after-school activity programme we conducted with 10–13 year olds in Seattle, Washington, in which participants explored, mapped, wrote and spoke about the spaces and experiences of their everyday lives. Within these practices, children negotiate autonomy and self-determination, and forward ideas, representations, and expressions of agreement or disagreement that are critical to their formation as political actors.

Keywords: children, democracy, political geography, public sphere, Seattle, spatial practice

Introduction

Habermas’s 1991 monograph, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, was a formative text for political geography. For scholars interested in democracy and civic engagement, one thread in this text has generated a great deal of productive enquiry – the notion that there existed a moment where certain kinds of secure, unthreatening spaces allowed for autonomous, rational debate about the future of society. In Habermas’s conceptualization, this moment of deliberative freedom is long gone. Yet this site and the deliberative practices associated with it represent ideal types that continue to guide scholarly and popular notions about democracy and civic engagement, and even the politics that may be activated through new technologies for communication and representation (Crossley and Roberts 2004). Moreover, critiques of Habermas’ original thesis have been equally galvanizing for scholars: some on the basis of exclusions from this ideal type of rational deliberative space; others problematizing the notions of reason and rationality as neutral categories unaffected by power relations in society (Fraser 1990; Howell 1993).

Here we use these debates about the public sphere and communicative action as an entry point to examining a persistent challenge that frames research on children’s geographies and politics: the challenge of recognizing dimensions of political formation and agency that are excluded or unrecognizable within both modernist political theorizations and the feminist and Foucauldian challenges to them. We respond to recent calls from geographers and others for research on children as political actors (Kallio 2008; Bosco 2010; Kallio and Häkli 2010; Skelton 2010), as well as efforts to confront abstract political and social theory with empirical data on the political lives of young people (Horton and Kraftl 2006; Hopkins and Pain 2007; Vanderbeck 2008; Jeffrey 2010). These two related calls both centre upon the foundational challenge of recognizing forms of political agency and practice that by definition fall outside existing theorizations.

Within modernist political theorizations, children cannot be recognized as political. They are effectively “always already” positioned outside of the public sphere and abstracted notions such as communicative action or “rational” speech. Some researchers suggest that part of what positions children in a disempowered or limited role is the notion that they are incapable of being political actors because they cannot make what are conceived within these frameworks as rational decisions (Cohen 2005) or rational argumentation (Thomas 2009; Kallio and Häkli 2010). Responding to these exclusions, many recent efforts to theorize the meanings and sites of children’s politics have turned to children’s spatial and bodily practices or their critical social knowledge (Skelton and Valentine 2003; Cope 2008; Kallio 2008; Bosco 2010).

These efforts to theorize children’s agency as embodied tactics and other forms of spatial practice have opened important new possibilities for recognizing certain everyday acts, behaviours and forms of knowledge as arenas of children’s politics. Here we complement and extend these discussions, showing children’s representational and dialogic practices, specifically their maps and writing about the spaces and experiences of their lives, as well as their everyday dialogues with adults, as additionally important sites of their politics. These representational and dialogic practices depart substantially from conventional forms of deliberative politics; neither can they be conceived solely as the forms of embodied practice or resistance which lie at the heart of much recent research on children’s politics.1 Yet we will show that children’s cartographic representations, and their dialogues of the everyday, can constitute a significant (yet under-examined) space for their politics and their formation as political actors.

The notion that children’s everyday dialogues (especially with adults) and their cartographic representations may be sites of their politics rests a bit uneasily with respect to critiques of modernist political theories and representational practices. Feminist re-readings of politics and the public sphere have quite appropriately problematized communicative relations between unequal actors (Fraser 1990; Young 1990; Howell 1993), and socio-political critiques of cartographic representation have emphasized its disciplining and marginalizing effects (Herb et al. 2009; Kingsbury and Jones 2009). Yet we suggest here that children’s everyday dialogues and cartographic representations may also be a site in which they negotiate autonomy and self-determination, and put forth ideas, representations, and expressions of agreement or disagreement with each other and with adults. These negotiations – practices of representational and narrative agency – are sometimes possible even within the uneven power relations and constrained circumstances in which children are so often positioned. Representational and narrative agency aid in the formation of a political subject, yet do so in ways that are generally unrecognized within the terms of most adult-centred political structures and practices. We rely on de Certeau’s notion of spatial stories and Bakhtin’s concept of dialogic relations to recognize these practices and politics.

Our argument here emerges from research conducted with 10–13 year olds over a nine month period in 2010. In an after-school activity programme housed at a Seattle public school, we offered a weekly class focused on exploring and mapping children’s everyday geographies. The class met weekly through the entire school year, from September until May, one of several activities offered as part of an after-school educational programme of a non-profit agency but housed at public schools. Enrolment in the after-school programme was optional, and students or their parents were free to choose from a number of different activities (writing, drawing, dance, sports, etc.). Our class, explained to the students as a computer mapping class, was introduced via information fliers, a recruitment table we convened during several lunch periods, as well as teacher or after-school programme staff referrals of specific students. Once we began teaching the class, other students were recruited by friends or siblings already participating. Over the course of the year, we worked with 10 children, though attendance varied from 2 to 8 at any given session. This variability speaks to the unstructured nature of this after-school programme (there was very little oversight of which students were present or which class they were actually attending) as well as family and household demands, as some student dropped out to care for younger siblings, or were required to return home early because of parent fears about neighbourhood violence.

The class included exploration and mapping of the students’ everyday activities, to draw out shared or different perceptions and experiences of the school, its surrounding neighbourhood and the children’s home neighbourhoods. The children mapped and described their daily movements within the school building, photographed and wrote about places on their daily journeys from home to school, guided us on walking explorations of their school neighbourhood, and created individual and collective maps of places they identified as important, good, bad, frightening, fun, and a host of other characteristics. The claims we develop here are based on participant observation conducted while teaching the class and content analysis of the children’s maps and map annotations. These after-school activities were part of a larger ongoing project studying the role of interactive mapping technologies in promoting children’s everyday spatial knowledge and catalysing political and civic engagement.2

The school we worked with enrols about 500 students, over 95 per cent of whom are racial or ethnic minorities and 75 per cent of whom qualify for a free and reduced meal programme for low-income families. Students, teachers, and administrators deal with a host of challenges, including violence in and around the school, an ageing physical infrastructure, and increasing oversight and interventions imposed as a result of failing to meet student performance benchmarks set out under federal No Child Left Behind policies. The neighbourhood surrounding the school has some of the highest levels of crime and poverty in the city, and has had some of Seattle’s highest levels of unemployment and foreclosure during the recent economic recession. But it is also the site of recent infrastructural improvements and investment, including new residential construction and retail services along its main arterial road. While welcomed by some residents, others are concerned these changes may be harbingers of gentrification. Notably, many of the students we worked with questioned whether the new services were in fact open to them or to any neighbourhood residents.3

Finally, before turning to recent debates about children’s politics, some semantic clarifications are in order. The literatures we engage use terms that include children, youth, teens, and young people, and apply them to a variety of age ranges. In discussing specific sources, we use whatever term was adopted by the originating author. We will refer to the students participating in our project as children, following Jeffrey (2010) and others who tend to apply this term to those under 15 years old. Yet we would underscore that as socially constructed, geo-historically contingent categories, terms such as children, youth, young people, or teens matter not just as a point of clarity. These categorizations are sites of institutional governance, determining, for example, who can exercise citizenship rights by voting, who is obliged to attend school, or who may give legal consent in a variety of settings (Ruddick 2003, 2007; Hopkins 2010; Skelton 2010). They also function as strongly held cultural symbols (such as Western notions of childhood as a period of innocence or children as needing to be sheltered, Valentine 1996), structure access to institutionalized opportunities for political participation, and shape assumptions about the sites and nature of children’s/youth political agency (Kallio and Häkli 2010; Skelton 2010).

Children and the political

Questions about children’s and youth politics have been taken up across a wide array of disciplines and research agendas. A great deal of this work has evaluated governmental programmes aimed at youth participation in policy- and decision-making (Fitzpatrick 1998; Matthews 2001; Matthews and Limb 2003), or sought to assess and explain the purported declining political engagement of young people (Youniss et al. 2002; de Vreese 2007; Bachen et al. 2008; Gerodimos 2008; Calenda and Meijer 2009; Kirshner 2009). The role of digital technologies and practices such as social networking, Web 2.0, GIS, and text messaging have received a great deal of attention in recent years, but again with an emphasis on youth participation in electoral politics or policy and planning venues (Amsden and g 2005; Dennis 2006; Kimber and Wyatt-Smith 2006; Berglund 2008; Flicker et al. 2008; Greenhow et al. 2009; Harris et al. 2010; Santo et al. 2010).

Critiques of these formal spaces and institutionalized venues for political participation have emphasized their limitations with respect to recognizing and including young people. Such sites tend to be conceived around adult notions of politics and the political (Matthews and Limb 2003; O’Toole 2003) and based on concepts such as citizenship that by definition cannot include children or youth (Skelton 2007, 2010). Fundamentally, these critiques argue, children are subjects who fall in between a host of social and institutional structures and definitions (Weller 2003; Kallio 2008; Sharkey and Shields 2008; Skelton 2010). They are often acted upon as citizens by institutions, but at the same time are not recognized by those same institutions as having full citizenship rights (Ruddick 2007). Gaskell (2008) for example notes a UK policy that requires certain behaviours of respect from young people, while failing to secure respect for them in their encounters with adults.

Efforts to theorize children’s politics beyond conventional understandings of (and forums for) rational debate and civic engagement have led to greater emphasis on children’s everyday life politics, understood as present in negotiations over social roles, power relations, and resources (Philo 2000; Skelton and Valentine 2003; Horton and Kraftl 2006; Hopkins and Pain 2007; Skelton 2010). These accounts of children’s politics draw strongly upon feminist theorizations of the political as encompassing structurally-mediated inequalities, social relations of everyday life, and negotiations over identities and subjectivities (Kofman and Peake 1990; Secor 2001; Brown and Staeheli 2003). In particular, this work locates the political in children’s spatial practices – their efforts to actively negotiate these structures, relations, and identifications through the everyday circumstances in which they find themselves. Bosco (2010), for example, points to children’s daily activities that contribute to social and political change, such as bilingual children helping immigrant parents participate in civic life. O’Toole (2003) and others (Matthews and Limb 2003; Wyness et al. 2004; Gerodimos 2008), identify as political children’s and young people’s articulations of their own views and demands. Weller (2003) and Cope (2008) look to contestations by (respectively) young people and children, especially their efforts to resist adult-imposed structures and rules, or to disrupt adult-dominated spaces such as school grounds, the street, and the home. These contestations are political, they argue, because they challenge adult control over spaces, institutions, and activities in which children are situated. Kallio (2008) similarly emphasizes contestation and protest, but focuses on bodily expressions of resistance or tactical acquiescence, arguing that in these practices, children struggle to rewrite adult norms.

Complementing these efforts to conceptualize and identify children’s politics within spatial practices, contestation, and bodily resistance, other scholars have focused on children’s critical perceptions and normative judgements about inequality and difference as sites of their politics. Bosco (2010) for instance emphasizes children’s ability to recognize political and economic inequality, and Kallio (2008) focuses on their capacity to distinguish between “friend” and “enemy”, with both emphasizing that making judgements is one expression of political agency. Wood and Cole (2007) also focus on critical perception, arguing that children’s politics (specifically around “the civic”) are evidenced not just in their ability to identify important civic events, but to discern the power relations circulating in and through them. Finally, Kallio and Häkli (2010, pp. 357–358) emphasize that children’s perceptions of socialization pressures can be considered political, when ‘children as intentional social beings relate to the subject positions offered by parental, (peer) cultural or institutional forces of socialization'.

Theorizing children’s perceptions and judgements as a site of politics allows us to recognize children as political even in circumstances in which they are not free to confront, act, or intervene. Yet these accounts do not detail precisely what it is about making a critical perception or judgement that constitutes a form of politics, running the risk of seeing all expressions of social knowledge as political, or framing children as political simply because they are knowledgeable social actors. To these points, we would argue that children’s critical perceptions/ judgements about inequality, subjectivity, and power relations enter the domain of the political when they constitute moments of political formation – when we can find evidence that children are recognizing and asserting themselves as particular subjects, in relation to others, to the structures in which they are situated, and to subject positions that may be imposed on them. This emphasis on political formation allows us to read children’s narrative, visual, and textual representations of their everyday and experiences as more than just evidence of their status as deeply knowledgeable social actors, but as actively negotiated sites of their politics.

Thus, the concept of the political that guides our exploration of children’s maps, dialogues, and narrations of their everyday spaces and experiences emphasizes the constitutive and transformative potentials of language and visual representations. There is a politics to these signifying narrations and representations, because in them, children form social and political awarenesses, articulate their identities, perceive how they and others are being positioned, and engage these positions and relationships implied by them. In short, in narrating and representing, meanings are formed, connections identified or forged, and relationships and social positions negotiated. These expressions of agency are neither exactly the politics of the body or of spatial practice, nor the politics of critical knowledge that have been central to recent discussions of children’s politics. Our reading of children’s maps, dialogues, and stories as sites of politics rests on a notion of language and visual representations as important terrains of children’s politics.4 These diverse articulations are a politics insofar as they make and remake social subjects, relations, and norms, and they are especially significant for those whose political agencies must be leveraged from below. To further develop the ideas, we turn next to de Certeau’s (1984) notion of spatial stories, and Bakhtin’s (1984,1993) concept of dialogical relations.

The spatial stories and dialogical relations of everyday speech

In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau (1984) theorizes the political agency of less powerful actors, asking how and where subjects positioned within structures of domination may exercise agency, autonomy, and self-determination. He argues that they do so in the practices and spaces of everyday life, occupying spaces in ways that resist their dominant coding, inserting their own interpretations and meanings into hegemonic knowledge, and behaving in ways that challenge the norm, or at least refuse to reproduce it. For de Certeau, these are tactics, which he differentiates from strategy, the spaces and practices created and controlled by more powerful agents. The concept of tactics, as well as de Certeau’s emphasis on practice, have been central theorizations in children’s geographies research, used to help illuminate politics from below, recognize forms of resistance not explicitly or intentionally articulated as such, and theorize the body as a site of children’s politics (Skelton and Valentine 2003; Kallio 2008; Jeffrey 2010).

We argue that de Certeau’s concept of spatial stories offers an important complement to this existing strand of work on children’s politics, providing a framework for theorizing how children’s politics may be practiced not just in their acts, behaviours, and bodily resistance, but in their representations and narrations of their everyday spaces, interactions and experiences. For de Certeau, spatial stories are narratives about places which imbue them with meanings, attributes, and norms – at once drawing upon and influencing the spatial practices of knowledgeable social actors in these places. For example, media characterizations of a neighbourhood as dangerous and dilapidated may be scripted such that they implicitly frame that place as “no go” areas. From a different perspective, maps or art produced by a community organization to script the neighbourhood as vibrant and growing could be spatial stories that transgress the boundaries scripted by other narrations.5

From this overall formulation, we would emphasize two additional points about spatial stories, to highlight their significance in political formation and agency. First, spatial stories are fundamentally an exercise of political agency. These stories may enact critical perceptions and judgements, recognize or negotiate inequality, or directly engage a host of social and spatial norms. Second, spatial stories are also inextricably linked to the formation of social actors. In the previous example, scripting a neighbourhood as a no go area implicitly or explicitly projects a notion of for whom the place is defined in this way. A spatial story that begins, ‘We can only go into this shop after school’ narrates not just a place and a bounding of access to it, but a social grouping - the “we” to which some places are open and others closed. As well, even this very simple story hints at the presence of other social actors and relations -those involved in dictating the conditions of access to the shop for others.

While de Certeau’s development of spatial stories as a concept only hints at their role in constituting and negotiating social actors/group and their relationships, these ideas take centre stage in Bakhtin’s scholarship on democracy in everyday life. Bakhtin (1984,1993) also looks to everyday life as a site where practical rationalities that negotiate social relations and agency are formed, and proposes that democracy works within the material consequences of everyday practices. Specifically, Bakhtin calls our attention to ‘creative dialogic reflections’ (in Roberts and Crossley 2004, p. 19), on the world, which he argues are an inherent part of everyday speech. Everyday speech, he argues, establishes dialogical relations – engaged interactions that position actors relative to others and to the world at large. It is this positioning of identity, subjectivity, and relationship that makes the dialogical relations of everyday speech an important site of politics. Bakhtin (1984) further suggests that everyday dialogue is a site of contestation, an arena in which people grapple with complexities, ambiguities, and the moral dilemmas of social life, situated within particular historical and geographical contexts. This emphasis upon the meanings negotiated, contested and reinforced in everyday dialogue allow us to recognize everyday dialogue as a realm of politics, even when these dialogues may occur between deeply unequal participants.

Together, these theorizations allow us to see children’s spatial stories as political on two levels. First, spatial stories play an important role in the formation of political subjects insofar as they are one medium or practice through which storytellers represent and position themselves and others as particular social actors in particular kinds of social relationships. Second, spatial stories exercise narrative or representational agency when they perceive, make judgements about, or re-read normative meanings.

Spatial stories and the formation of the political

We now turn to examples from our work with children to show how attention to their representations, spatial stories, and dialogic relations can illuminate forms of political agency and sites of political formation that have received less attention in research to date. In our broader project on collaborative learning, interactive mapping, and civic engagement, we conducted a series of weekly classes in an after-school enrichment programme at a public school. The activities included exploration and observation of the participants’ movements through the city, their home and school spaces, and other places they encounter and experience in an ordinary day, as well as mapping, writing, and reflective discussion related to these everyday journeys. In the children’s maps and writing, as well as in our interactions with them, we found copious examples of critical perceptions and judgements of inequality, power relations, subject positions, and social and spatial characterizations set out by adults and peers. These expressions were present in the children’s cartographic and written representations of their everyday spaces, the narratives they constructed in and through these maps, and their dialogical relations with us and with other adults encountered in their everyday lives.

Spatial stories: representing and asserting autonomy in everyday life

The children’s maps of their experiential geographies of home, school, and neighbourhood constituted an important site for their spatial stories. In some of the mapping activities we led, they were prompted to choose key places and movements in their everyday lives, and to locate these sites or journeys on a simple base map. They also wrote annotations for the map objects they created, in response to the prompts, ‘What is it? What is it like? Why is it important? Why did you pick it?’. In some sessions, the children created their maps using a web-based mapping platform we developed for this project. Our mapping platform is an open-source web service that offers a simple set of tools for adding points, lines, and areas over a street map of the local area; associating text-based comments with their map objects; or adding comments and questions to map objects added by their classmates. Other mapping activities were offline, as in one where the children sketched the school neighbourhood on simple line drawings, marking sites they wanted to take us and their classmates in an upcoming group exploration of the area. They also worked at very small scales, as in a “micro-mapping” of their movements throughout the school grounds, in which they used digital drawing tools to mark and annotate a digital blueprint of the school. We developed this last exercise in response to the extremely limited movements of several of our regular student participants. For reasons of limited transportation, family care responsibilities, parental fears about neighbourhood violence, and cost constraints on joining youth activities outside of school, many of the participating children could only identify home and school as important sites in their everyday lives. Concentrating on their movements in and around the school itself enabled all the participants to join in exploring, discussing, and mapping their everyday geographies, even those whose daily movements were highly constrained.6

The rich methodological debates from children’s geographies research emphasize that adult-child power asymmetries have a strong influence on what and how children may share or withhold about their knowledge, experiences, and feelings (O’Toole 2003; Cahill 2007; Cope 2008; Gallagher 2008; Travlou et al. 2008; Anderson and Jones 2009), and with this in mind, several details about the nature of adult/institutional control in our project are important to note. Our activities were conducted as part of an institutionalized co-curricular after-school programme, and so cannot be considered child-led, nor were they conceived as participatory action research. We intentionally left class activities open-ended and adapted them to respond to the children’s interests and experiences, but the class was nonetheless designed and facilitated by us in an instructional role. By virtue of the class being in a school-based academic enrichment programme, the children were subject to a host of explicit and tacit norms and expectations. Conducting our activities in the space of the school seemed to set up an implicit expectation for the children that they should follow regular school day rules and behaviours. Our role as conveners of an after-school “class” meant that to a certain degree, the children perceived us as “teachers”.

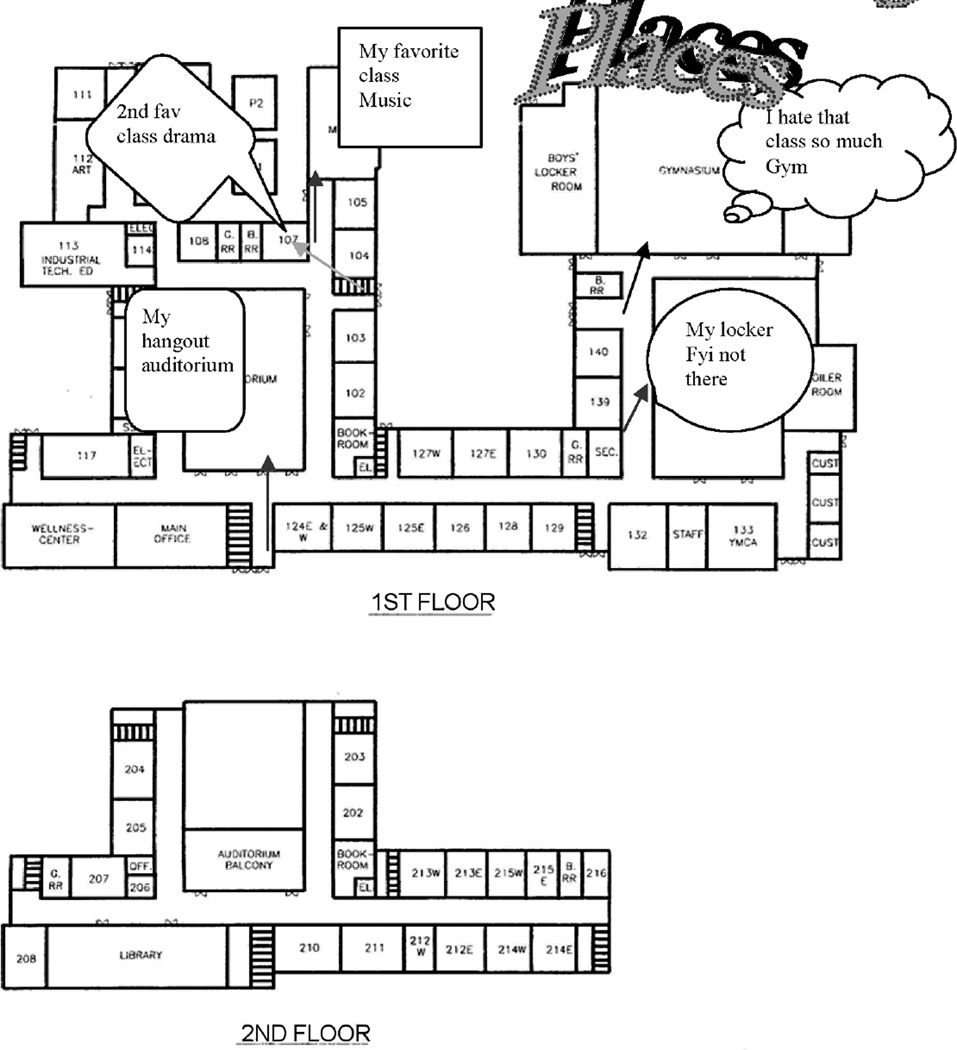

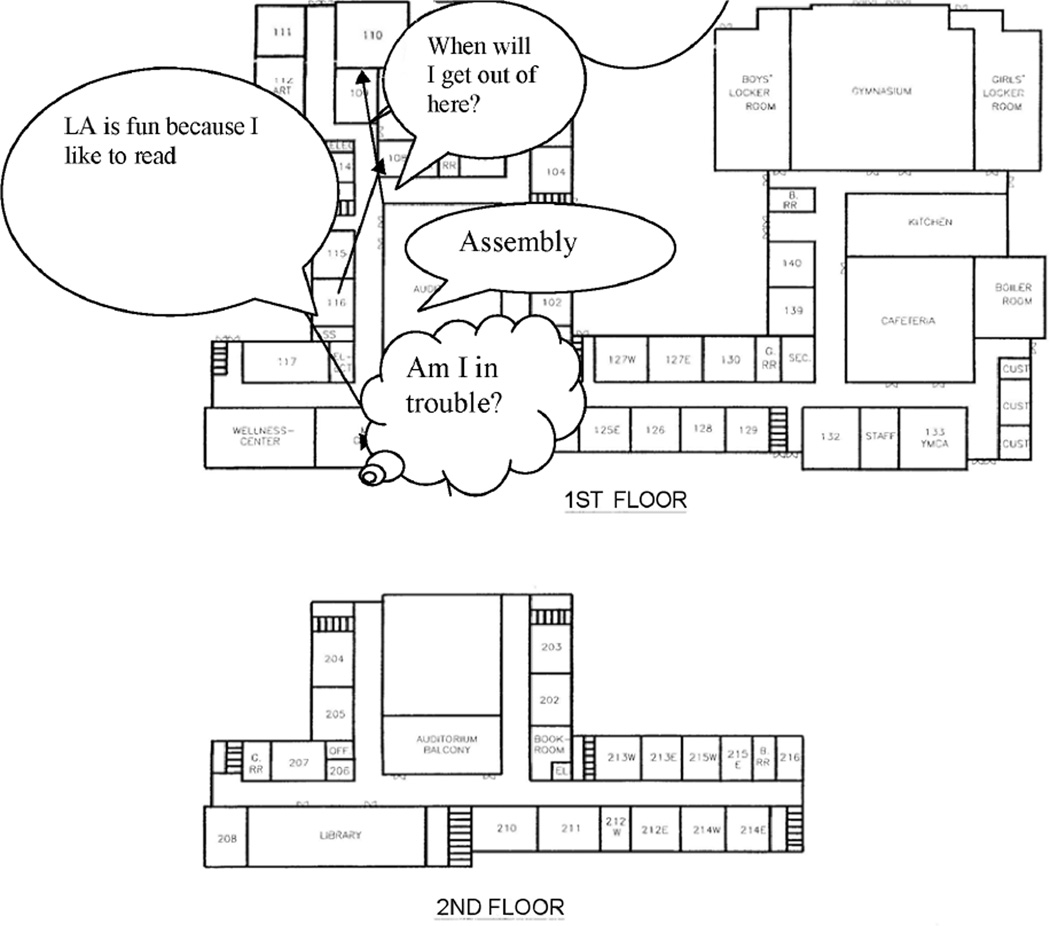

Yet even amidst these constraints, the participating children seized the mapping activities as an opening to produce spatial stories which challenged, rewrote, and sought to erase a wide range of conditions, characterizations, and even emotions imposed upon the children, or which imposed boundaries or limits on them. For example, some children annotated school spaces in language forbidden by their teachers during the regular school day, expressing sentiments they were not allowed to voice in class (and also at home). Several of the maps of their movements throughout the school included the annotation ‘I hate this class’ atop the location of a particularly disliked class (Fig. 1). Other children used their maps to represent themselves in ways that they might conceal in their everyday interactions with their peers. One of the boys annotated a classroom with a text box that said, ‘LA [language arts] is fun because I like to read’ (Fig. 2). This representation of himself as someone who likes a class and enjoys reading is noteworthy in the face of significant peer pressure to dislike school and not appear to be too smart.7 The children’s maps questioned how others perceive them based on the spaces they occupy in the school. The boy whose map notes liking language arts was also regularly in the principal’s office during the day, and he annotated this site with a cartoon-style thought bubble that asked, ‘Am I in trouble?’. Of course, there are many reasons why a student might be in this office, but for American students, ‘sent to the principal’s office’ is a ubiquitous symbol implying some sort of disciplinary action. This student had very limited English skills, so we were not able to determine exactly why he was going to the office, but he did make it clear that he was not “in trouble”, but concerned that other students would think he was.

Figure 1.

BillyBobBingBong’s map of her everyday microgeographies in school.

Figure 2.

Sadique’s map of his everyday microgeographies in school.

In other cases, the children’s social and spatial practices were revealed through the omissions in their maps, in their choice to leave certain things and places unrepresented. Several students did not put any map objects or annotations on the second floor of the school, and we assumed at first that they never went to the second floor. Later they explained that yes, the second floor was a regular part of their school day, but it was the site of classes, activities, or people they did not like (Figs 1 and 2 both show the “empty” second floor). In these absences, we see a practice of representational agency: the children opt to omit from their representations the places and experiences they do not like, even as they are still compelled to go there as part of their regular school day. They are not free to absent their bodies from these spaces and the people and activities connected to them, yet they are free to erase the spaces from their representations.

In their lived practices, these participating children generally followed the norms, tacit and explicit, set out by their parents, teachers, and peers. It was clear in our own observations, in the comments of their teachers and youth leaders, and in the children’s own self-representations that, for the most part, they went where they were supposed to go, and refrained from saying what was forbidden. Yet in the representational spaces of the map, these same children created stories of places and selves that work against the encodings and constraints foisted on them by others. These sorts of practices are exactly what de Certeau’s emphasis on tactics in everyday life allow us to recognize as political, only in this case, the tactics emerge in representational spaces – the spatial stories activated through the children’s mapping exercises. In a context in which children are normally quite disempowered – the spaces and activities of their formal school day – our participants used the processes and products of their mapping efforts to rewrite, question, and sometimes just react to these normative power relations. From these examples we further suggest that the political is found not only in children’s bodily resistances in material spaces or direct confrontations with others, but can also be constituted in their intentional and reflective representations of these spaces and interactions.

Negotiating (political) selves in dialogue

In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau emphasizes the productive power of spatial stories, specifically their capacity to script social actions that are possible or not possible in certain spaces, and to signify spaces with particular meanings. What is under-emphasized in his unfolding of this concept is the relational nature of spatial stories. As stories script spheres of action or spatial meanings, they do so for particular narrators and the actors in their stories, and in this way, spatial stories are fundamentally relational. We draw this point from Bakhtin’s account of everyday dialogue, which emphasizes that dialogues are always relational, in that their content positions social actors vis-à-vis one another, scripts particular subject positions, and sets the terms of (democratic) engagement among individuals and social groups. Adding this Bakhtinian attention to the relationality of everyday dialogue makes apparent that spatial stories have the potential to script and rescript not just spaces, but subjects and their relationships to one another, to subject positions, to the world at large, further underscoring the political nature of everyday speech. From this conceptualization we can recognize children’s dialogues as a realm of politics, because they constitute moments of political formation, actively negotiated by children as they situate themselves and others through the interactions.

Several of our after-school sessions involved the students guiding us and their classmates around the school and its surrounding neighbourhood, taking us to places they deemed significant and describing their experiences, observations, and feelings. In these excursions, with no prompting, they consistently initiated and sustained conversations with us about these spaces and the things that happen in them. On one exploration, as we walked along the sidewalk looking at the school building, several students announced that they ‘hate this school’. Picking up the cue, we asked why, and together they pointed to the unfairness of a school day that is much longer for them than for their friends who attend other schools. Asked why they have such a long school day, one boy responded (to the affirmative nods of his classmates), ‘Because they think we’re dumb.’ In a simple way, this dialogue could be interpreted as the children’s misunderstandings of regulations set in place by adult institutions. As mandated by No Child Left Behind measures, their school has an extended schedule because it has not reached benchmarks in annual achievement tests. Yet if we read this exchange with the students as a story about place, individual and group identities, and adult characterizations of children, a much different picture emerges. The children’s conversation with us about their school is also fundamentally their story to us about the students who go there, their own self-perceptions, and their critical awareness of how others see them. In his assertion, ‘They think we’re dumb’, it is clear that the narrator has not adopted this position as his own and he intervenes to redirect our perceptions of him and his classmates (he delivered the statement with a substantial dose of scorn in his voice). His statement and his classmates’ agreement, shows their clear recognition of how they are being positioned by others. It also shows their determination to counter these characterizations. “Of course we know better”, their collective contributions to the conversation implied, “we are not dumb and you, the adults with whom we are having this conversation, also know better.”This dialogue extended into other parts of the exploration activity, when they took us inside to view a bulletin board in the school, which listed some of their names alongside those of other students with high grades.8

These and other conversations with the children during guided explorations highlighted their awareness of social positions foisted on them by adults they encounter in their everyday activities. Further, the children’s dialogues give some indication of their active agency in negotiating these positionings and interactions. Particularly important to these children were the interactions they have with adults outside home and school settings, often in small corner stores, mini-marts and fast food restaurants surrounding the school or close to home.9 These sites were consistently present and central in their spatial stories. In their maps and class excursions, they identified these locations as important sites in their everyday geographies – places they go to buy snacks for themselves, siblings, and friends, or occasionally to run errands for their parents. Their overwhelming focus in these stories was less upon what they bought or consumed but on their interactions with adults in these sites. Their spatial stories revealed that their dialogues with adults in these sites are an important terrain for negotiating identities and social relations – key elements in the formation of political actors. For example, one of the children told us a story of racism and xenophobia as we walked by a mini-mart attached to a gas station. He began by saying that he and his friends do not go into this shop and ‘you shouldn’t either.’ He related that some months earlier, he was in the store to buy a soda and was taking a long time to make up his mind, when the shopkeeper forced him to leave. When he told her that he had not yet made his choice, she continued to insist he leave, finally saying, ‘You’re not in Africa anymore!’ as she ejected him from the store. Other children related similar stories on our excursions, and many of them included these exclusionary interactions in their maps of their important places. One girl, for example, placed a marker on her map to represent a fast food restaurant by the school and annotated, ‘They have a new rule that three students allowed in at a time so I feel bad.'

Yet not all of the children’s dialogues with adults in nearby shops were discriminatory or demarcated spatial boundaries on the basis of age or race. Some of the children’s dialogues fostered representations of themselves as capable trustworthy social actors. Following the story of the racist shopkeeper above, another child on the excursion pointed down the street to a second shop ‘where we all go instead’. His explanation of why this shop was better emerged in the following conversation:

YouSawMe: 10 I was buying candy for me and my friends and I needed like 75 cents more. She let me go.

Sarah: You mean they’re okay if you come back and pay later?

YouSawMe: No, they just let you have it!” [at this point, several other children joined in, to relate similar experiences in this shop].

These stories, both positive and negative, illustrate how dialogues with adults constitute a key site of children’s political agency and formation. In these interactions, they assert autonomy, perceive injustice, and sometimes find themselves constructed as different, as bad, or as disempowered subjects who may be ejected or harassed on the basis of age, race, and other markers of social difference. But as illustrated in the last story, these dialogues are also relational spaces in which they sometimes find themselves recognized and affirmed as people who are capable, trustworthy, or deserving of generosity in the eyes of others.

The examples above are only a few of the important conversations the children had with one another and with us, or recounted to us from other experiences. These narrative encounters are much different than the spatial contestations or bodily resistances on which much of the discussion of children’s politics has focused. Yet for children, these self-initiated spaces of dialogue, especially with adults who are comparative strangers and neither family nor regular teachers, are an important sphere into which their political selves may emerge. These interactions are political in that they centre upon the significations being assigned through social engagements to the category of child (also potentially other social categories, such as immigrant in the example of the racist shopkeeper). In these dialogic relations children situate themselves in relation to each other, to adults, and to the world at large, and respond to the ways that others try to situate them. In these moments they are encountering and negotiating divergent subject positions, often intermingled with accompanying spatial constraints.

In the examples presented here, these negotiations of individual and collective identities, capabilities, and characteristics are occurring in two arenas: the children’s original experiences with adults in the spaces and institutions of their everyday lives, and also the spatial stories they narrate to us in their maps and conversations about these interactions, experiences, or places. Such narrative moments of representing an experience or interaction provide an important opening for children’s political agency as they select out particular sites and interactions to include in their narrations, and make choices about how they will articulate and represent these stories. Through these choices, the children demonstrated their critical agency in perceiving a variety of inequalities, exclusions, and inclusions in the first place, and exercised it again by selecting and articulating these in dialogue with us. Their narrations and representations are fundamentally relational, insofar as the speakers use their stories to reposition themselves to us as good, trustworthy, fair, compassionate, and savvy kids.

This is not to suggest that we observed no direct and overt forms of resistance, nor any embodied tactics such as those that have been so well-represented by other scholars studying children’s geographies and politics. Certainly the boy who was forced out of the corner store did put up some initial resistance and the children’s avoidance of shops where they were treated badly can be seen as a sort of tactic. Yet in many instances, the children did not or could not directly challenge the positionings or exclusions they were encountering. But in their spatial stories about these people, places and encounters – in this case emerging in maps and dialogue – the children responded with their own assertions of who they are and what they are like. For actors whose opportunities to directly confront, self-represent, or even speak are often severely constrained, the narrative representations of a diverse range of spatial stories are an extremely important site of political agency.

Further, we argue that these spatial stories and dialogic relations are deeply significant to children’s politics because they constitute sites for the formation of political selves; they are moments in which children recognize who others assume them to be, articulate who they are, and negotiate these positioning through a range of spaces and relationships that demarcate difference, identity, and power. Bakhtin’s emphasis upon the politically formative is not an end-state to be achieved, but rather is something that is in constant formation and reformation. From this conceptualization it is possible to ask, for children and other actors, where and how these political formations occur, without suggesting that these actors are somehow unformed or pre-political.11 As we illustrate here, children’s spatial stories and the dialogic relations of their everyday lives are two such sites of political formation, even in an arenas that remain restrictive or adult controlled.

Discussion

Children’s politics may be practiced in their cartographic representations, the spatial stories that circulate in and around these representations, and in dialogic relations of their everyday lives. Attention to these practices illuminates modes of children’s politics that are not visible through the lenses of modernist democratic and political theory, nor through the focus on embodied forms of resistance that has been prominent in recent research on children’s geographies (Harker 2005; Horton and Kraftl 2006; Kallio 2008). As well, the examples presented here underscore the persistent political significance of representations, particularly cartographic representations. For children or other social actors whose opportunities for self-representation are comparatively limited, the materiality of the map or the “constructability” of the yet-to-be-mapped page serve as extremely important openings for self-representation, negotiation of subject positionings, and ultimately, their assertions of political agency. Indeed, in making a similar case vis-à-vis marginalized adults, Herb et al. (2009) argue that however fluid, constructed and ultimately problematic cartographic representations may be, maps constitute a politically and socially significant opening to define, author, and signify.

We have argued that children’s narrations and representations of their everyday encounters can play an important role in their positioning as social subjects and are a site where they can shape this positioning. In these tellings and mappings, children assert who they are and take an active role in how they are understood and recognized in the world. Children’s representations and narrations of their interactions in the school, the mini-mart, the home, and other everyday spaces are articulations in which they not only perceive but negotiate social differentiation, in connection and interaction with others. Their dialogues and maps are interventions into particular social relations, constituting sites and interactions where their positions, their relationships, and their agency to negotiate them are formed and reformed.

These arguments emerge from our engagement with recent debates in children’s geographies about the meanings and sites of children’s politics, in particular efforts to grapple with the fundamental problematic of recognizing practices that are inconceivable within existing political theory or manifest in sites and forms not typically understood as political (Ruddick 2003, 2007; Kallio and Hakli 2010; Skelton 2010). Our focus here upon the spaces and interactions of children’s everyday lives draws strongly upon the propositions in this literature that children’s politics are present in their spatial/body practices, as well as their critical social knowledge (Horschelmann 2008; Kallio 2008; Bosco 2010; Kallio and Hakli 2010). This body of work has done a great deal to render children’s politics visible, by conceiving of them exercised in spatial practices and tactics from below (de Certeau 1984), yet these formulations do not explicitly treat our underlying challenge of how to situate children’s speech acts or visual/cartographic representations. While these engagements could certainly be considered a form of tactics or spatial practice, neither framing explicitly considers the specific representational or narrative agencies of telling and mapping. It was these gaps that led us to de Certeau’s complementary notion of spatial stories, which does speak to these dimensions of the everyday agencies of less powerful actors, as well as to Bakhtin (1984, 1993), whose work on dialogical relations highlights the political relationality that is established and negotiated in language and communications (see also Gardiner 2004).

Our effort to illuminate children’s politics of articulation, which we locate here in their efforts to ascribe, communicate, and re-write social meanings in narrations and visual representations of everyday spaces and experiences, complements and extends the core theorizations of children’s politics that have emerged from prior research overt the past decade or more. We show here how children’s narrations and representations can afford new insights into political agencies exercised in sites that might otherwise appear closed to negotiation. The examples we have considered here – maps created in an after-school programme, dialogues with adults, the lived spatial constraints of children’s everyday experiences – are all problematic for children in a variety of ways. And yet, even operating within strong constraints, children’s narrations and representations serve to make and remake social subject, relations, and norms. In short, children’s articulation matter as sites of political formation where they form and know themselves and others as situated actors in the world. These politics of articulation are extremely important for all children, but especially so for those who have very limited opportunities to position themselves in relation to a wider world.

As noted previously, this paper emerges from an ongoing multi-year research project on collaborative learning, interactive mapping technologies, and civic engagement. In other forums, we offer contributions closely related to the points discussed here. Mitchell and Elwood (forthcoming a) speaks in more detail to the pedagogies of the project and their significance. We argue that exploring local histories and geographies via collaborative digital mapping can increase children’s interest in civic participation, in part because these learning activities help them make connections between lived experiences and contingent social, political, and economic structures. Mitchell and Elwood (forthcoming b), like this manuscript, also uses our work with children to engage debates about the boundaries of the political, but with a more explicitly methodological focus. Specially, we consider the limits of methodologies drawn from non-representational theory, arguing that these approaches decouple politics from relations of power, leaving them unable to discern the nuanced socio-political connections forged through methodological encounters with children.

In its broader implications, our effort to show how children negotiate political formation and agency in their narrations and representations speaks back to debates about the potential and failings of conventional deliberative forums (Fraser 1990; Young 1990; Howell 1993; Crossley and Roberts 2004). These feminist and Foucauldian challenges to modernist political theory have thoroughly demonstrated the impossibility of an idealized public realm for communicative deliberation that forms political actors and mutually-held understandings. Yet these ideals still undergird many of the collaborative practices that are part of participatory democracy and civic engagement forums in the North American context we have examined here. From the deliberative “one on one” mini-dialogues that are part of the standard repertoire of community planning and community development, to the service learning and public citizenship initiatives that are ubiquitous in American public schools, children (and their later adult selves), ideal notions of rational speech, communicative action, and understandings across difference are all around us. Attention to the political formation and agency that are created and expressed in narration and representation within such forums allows us to imagine and nurture ways for less powerful actors to operate within them.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the contributions of research assistants Ryan Burns, Elyse Gordon, and Tricia Ruiz, as well as participating students and teachers/YMCA leaders. This work was supported by the National Geographic Education Foundation (#2008-UI03); and the Spencer Foundation (#20100052). Thoughtful feedback from reviewers and editors has helped us sharpen the article.

Footnotes

As much recent critical cartography research suggests, mapping is both an embodied and representational practice (Del Casino and Hanna 2005; Crampton and Krygier 2005; Wilson 2011). However, here our focus is the representational dimensions of maps and mapping, not their embodied practices.

Our larger research project also includes additional activities conducted at other schools and in regular school-day classroom settings. Further findings from this project that draw from both the after-school programme and regular classroom activities are forthcoming in Mitchell and Elwood (forthcoming a, forthcoming b).

One boy, describing sites on his neighbourhood map, astutely noted that a new “drive up” national chain coffee shop was only intended for those travelling by car through the neighbourhood. Calling our attention to the absence of interior seating or any pedestrian paths to the service windows, he said, ‘Yeah, [this chain store] came to our neighbourhood. But it’s not for us. We can’t go there – it’s only for people driving through here.’

There is some existing discussion of dialogue and language in research on children’s geographies and politics. Methodological contributions such as Walker et al. (2009) argue the importance of unstructured talk as a means for researchers to build rapport with young people. Habashi (2008) examines language as evidence of political socialization, in her work on children’s use of terms emerging from Palestinian resistance. Here we focus less on particular language of specific political practices, and more upon the relational exchanges and political formation that emerge through everyday dialogue.

Spatial stories as de Certeau conceives them are not limited to narrative or textual/visual representations, but might also be performative. Here, however, we focus on narratives and representations.

There is a great deal of prior work on participatory mapping with children, especially as regards the potential of online or GIS-based mapping technologies to facilitate greater access for young people or broaden the range of ways their knowledge and needs might be included in planning and decision making (e.g., Dennis 2006; Berglund 2008; Travlou et al. 2008). A central debate in this research has been the capacity of GIS and other digital spatial technologies to represent diverse expressions of knowledge or facilitate particular modes of participation by children or young people. These are important considerations, of course, but we focus here on the ways that maps and mapping constitute representational practices that reflect and shape social, political, and spatial relations.

Indeed, a friend of his reported that he did not like to be seeing coming into our after-school class and did not tell anyone he was in it because ‘everybody says it’s the nerd class. But at least nerds are smart!’

While we focus here on the children’s efforts to position themselves in our eyes through these collective conversations, it is also important to note that these interactions occurred in the presence of peers. No doubt some of their comments and points of concern (and also things they chose not to say) were in part motivated by how they want to position themselves in the eyes of the classmates.

Ross (2007) and Cope (2008) also show children’s interactions with adults (especially shopkeepers) to be an important aspect of their engagement with their broader community, often interpreted by the children through the positive and negative behaviours of these adults towards them. To this, we would add that these interactions contribute to children’s political formation and subjectivities.

For mapping and writing activities in our class, children selected their own pseudonym. YouSawMe was this boy’s chosen pseudonym. Where possible, we have provided direct quotes of our exchanges with the children, but in many cases, a narrative description of the encounter will have to suffice. Our interactions with the children were not video or audio recorded and often involved multiple children (and adults) in conversation. Making field notes immediately after our class sessions, we only included direct quotes when we felt fully confident of our own exact statements and those of the participating children.

Of course, sites of political formation for children are often different from those of adults, who for example, would not likely experience some of the exclusions described above, such as being denied entry to a restaurant in groups. Yet other moments of political formation described above occur without regard to their status as children, such as the boy’s encounter with the racist shopkeeper.

Contributor Information

Sarah Elwood, Department of Geography, University of Washington, Box 353550, Seattle, WA 98195, USA, selwood@uw.edu.

Katharyne Mitchell, Katharyne Mitchell, Department of Geography, University of Washington, Box 353550, Seattle, WA 98195, USA, kmitch@uw.edu.

References

- Amsden J, Vanwynsberghe R. ‘Community mapping as a research tool with youth’. Action Research. 2005;3(4):357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Jones K. ‘The difference that place makes to methodology: uncovering the “lived space” of young people’s spatial practices’. Children’s Geographies. 2009;1(3):291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bachen C, Raphael C, Lynn K-M, Mckee K, Pffllippi J. ‘Civic engagement, pedagogy, and information technology on web sites for youth’. Political Communication. 2008;25(3):290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin M. Rabelais and His World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin M. Toward a Philosophy of the Act. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund U. ‘Using children’s GIS maps to influence town planning’. Children, Youth and Environments. 2008;18(2):110–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bosco F. Play, work or activism? Broadening the connections between political and children’s geographies. Children’s Geographies. 2010;8(4):381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Staeheli LA. “Are we there yet?” Feminist political geographies. Gender Place and Culture. 2003;10(3):247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill C. Doing research with young people: participatory research and the rituals of collective work. Children’s Geographies. 2007;5(3):297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Calenda D, Meijer A. ’ Young people, the Internet and political participation: findings of a web survey in Italy Spain and The Netherlands’. Information, Communication and Society. 2009;12(6):879–898. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen EF. Neither seen nor heard: children’s citizenship in contemporary democracies. Citizenship Studies. 2005;9(2):221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cope M. Patchwork neighborhood: children’s urban geographies in Buffalo, New York. Environment and Planning A. 2008;40(12):2845–2863. [Google Scholar]

- Crampton JW, Krygier J. An introduction to critical cartography. ACME. 2005;4(1):11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley N, Roberts JM. After Habermas: New Perspectives on the Public Sphere. Oxford: Blackwell; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau M. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Del Casino VJ, Jr, Hanna SP. Beyond the “binaries”: a methodological intervention for interrogating maps as representational practices. ACME. 2005;4(1):34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis SF. Prospects for qualitative GIS at the intersection of youth development and participatory urban planning. Environment and Planning A. 2006;38(11):2039–2054. [Google Scholar]

- De Vreese CH. Digital renaissance: young consumer and citizen? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2007;611:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick S, Hastings A, Kintrea K. Including Young People in Urban Regeneration: A Lot to Learn? Bristol: Policy Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S, Maley O, Ridgley A, Biscope S, Lombardo C, Skinner HA. e-PAR: using technology and participatory action research to engage youth in health promotion. Action Research. 2008;6(3):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser N. Rethinking the public sphere: a contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text. 1990;25/26:56–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M. “Power is not an evil”: rethinking power in participatory methods. Children’s Geographies. 2008;6(2):137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner ME. Wild publics and grotesque symposiums: Habermas and Bakhtin on dialogue, everyday life and the public sphere. In: Crossley N, Roberts JM, editors. After Habermas: New Perspectives on the Public Sphere. London: Blackwell; 2004. pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell C. “But they just don’t respect us”: young people’s experiences of (dis)respected citizenship and the New Labour Respect Agenda. Children’s Geographies. 2008;6(3):223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gerodimos R. Mobilising young citizens in the UK: a content analysis of youth and issues websites. Information, Communication and Society. 2008;11(7):964–988. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhow C, Robelia B, Hughes JE. ‘Learning, teaching and scholarship in a digital age. Web 2.0 and classroom research: what path should we take now?’. Educational Researcher. 2009;38(4):246–259. [Google Scholar]

- Habashi J. Language of political socialization: language of resistance. Children’s Geographies. 2008;6(3):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas J. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harker C. ‘Playing and affective time-spaces’. Children’s Geographies. 2005;3(1):47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Harris TM, Rouse LJ, Bergeron SJ. The Geospatial Web and local geographical education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education. 2010;19(1):63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Herb GH, Hakli J, Corson MW, Mellow N, Cobarrubias S, Casas-Cortes M. Intervention: mapping is critical! Political Geography. 2009;28(6):332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins P. Young People, Place and Identity. London: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins P, Pain R. Geographies of age: thinking relationally. Area. 2007;39(3):287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Horschelmann K. Populating the landscapes of critical geopolitics – young people’s responses to the war in Iraq (2003) Political Geography. 2008;11(5):587–609. [Google Scholar]

- Horton J, Kraftl P. What else? Some more ways of thinking and doing “Children’s Geographies. Children’s Geographies. 2006;4(1):69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Howell P. Public space and the public sphere: political theory and the historical geography of modernity. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 1993;11(3):303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey C. Geographies of children and youth I: eroding maps of life. Progress in Human Geography. 2010;34(4):496–505. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio KP. The body as a battlefield: approaching children’s polities. Geogrqfska Annaler: Series B Human Geography. 2008;90(3):285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio KP, Hakli J. Political geography in childhood. Political Geography. 2010;29(7):357–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber K, Wyatt-Smith C. Using and creating knowledge with new technologies: a case for students-as-designexs. Learning Media and Technology. 2006;31(1):19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury P, Jones JP. Walter Benjamin’s Dionysian adventures on Google Earth. Geoforum. 2009;40(4):502–513. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner B. “Power in numbers”: youth organizing as a context for exploring civic identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19(3):414–440. [Google Scholar]

- Kofman E, Peake L. Into the 1990s: a gendered agenda for political geography. Political Geography Quarterly. 1990;9(4):313–336. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H. Citizenship, youth councils and young people’s participation. Journal of Youth Studies. 2001;4(3):299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H, Limb M. Another white elephant? Youth councils as democratic structures. Space and Polity. 2003;1(2):173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K, Elwood S. Creating engaged students and civic actors through mapping local history. Journal of Geography. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2011.624189. forthcoming a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K, Elwood S. Mapping politics: children, representation, and the power of articulation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. doi: 10.1068/d9011. forthcoming b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole T. Engaging with young people’s conceptions of the political. Children’s Geographies. 2003;1(1):71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Philo C. “The corner-stones of my world”: editorial introduction to special issue on spaces of childhood. Childhood. 2000;1(3):243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JM, Crossley N. Introduction. In: Crossley N, Roberts JM, editors. After Habermas: New Perspectives on the Public Sphere. Blackwell; London: 2004. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ross NJ. “My journey to school…”: foregrounding the meaning of school journeys and children’s engagements and interactions in their everyday localities. Children’s Geographies. 2007;5(4):373–391. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddick S. The politics of aging: globalization and the restructuring of youth and childhood. Antipode. 2003;35(2):334–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddick S. At the horizons of the subject: neo-liberalism, neo-conservatism and the rights of the child, Part One: from “knowing” fetus to “confused” child. Gender, Place and Culture. 2007;14(5):513–527. [Google Scholar]

- Santo CA, Ferguson N, Trippel A. Engaging urban youth through technology: the Youth Neighborhood Mapping Initiative. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2010;30(1):52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Secor AJ. Toward a feminist counter-geopolitics: gender, space and Islamist politics in Istanbul. Space and Polity. 2001;5(3):191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey A, Shields R. Abject citizenship -rethinking exclusion and inclusion: participation, criminality and community at a small town youth centre. Children’s Geographies. 2008;6(3):239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton T. Children, young people, UNICEF and participation. Children’s Geographies. 2007;5(1–2):165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton T. Taking young people as political actors seriously: opening the borders of political geography. Area. 2010;42(2):145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton T, Valentine G. Political participation, political action and political identities: young D/deaf people’s perspectives. Space and Polity. 2003;1(2):117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ME. The identity politics of school life: territoriality and the racial subjectivity of teen girls in LA. Children’s Geographies. 2009;1(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Travlou P, Owens PE, Thompson CW, Maxwell L. Place mapping with teenagers: locating their territories and documenting their experience of the public realm. Children’s Geographies. 2008;6(3):309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine G. Angels, devils: moral landscapes of childhood. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 1996;14(5):581–599. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbeck RM. Reaching critical mass? Theory politics, and the culture of debate in children’s geographies. Area. 2008;40(3):393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Walker M, Whyatt D, Pooley C, Davies G, Coulton P, bamford W. Talk, technologies and teenagers: understanding the school journey using a mixed-methods approach. Children’s Geographies. 2009;7(2):107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Weller S. “Teach us something useful”: contested spaces of teenagers’ citizenship. Space and Polity. 2003;1(2):153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MW. “Training the eye”: formation of the geocoding subject. Social and Cultural Geography. 2011;2(4):357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Cole S. Can you do that in a children’s museum? Museums and Social Issues. 2007;2(2):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wyness M, Harrison L, Buchanan I. Childhood, politics and ambiguity: towards an agenda for children’s political inclusion. Sociology. 2004;38(1):81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Young IM. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J, Bales S, Christmas-Best V, Diversl M, Mclaughlin M, Silbereisen R. Youth civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12(1):121–148. [Google Scholar]