Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify mRNA targets of dysregulated miRNAs through the integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression profiling in men with normal versus impaired spermatogenesis. The expression of mRNAs and miRNAs in testicular tissues obtained from males with non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA, n = 4) or obstructive azoospermia (OA, n = 3) with normal spermatogenesis was analyzed using microarray technology. Some of the most interesting results were validated by real time PCR using samples from the same cohort. Ninety-three miRNAs and 4172 mRNAs were differentially expressed in the NOA and normozoospermic OA patients. In addition to confirming that significantly dysregulated genes and miRNAs play pivotal roles in NOA, promising correlation signatures of these miRNA/mRNA pairs were discovered in this study. The functional classification of the miRNA/mRNA pairs revealed that differentially expressed genes were most frequently associated with spermatogenesis, the cell meiosis, the cell cycle, and the development of secondary male sexual characteristics. This is the first systematic profiling of both mRNA and miRNA in testicular tissues of patients with NOA and OA. Our results indicate that the phenotypic status of NOA is characterized by the dysfunction of normal spermatogenesis when compared with OA or normozoospermic males.

Infertility is defined as the inability to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse and affects approximately 10%–15% of consulting couples. Approximately 40%–50% of infertility cases involve male factor infertility1. A substantial proportion of male infertility is accompanied by azoospermia (defined as the complete absence of spermatozoa upon examination of the semen) caused by obstruction of the excurrent ductal system (obstructive azoospermia, OA) or by testicular failure (non-obstructive azoospermia, NOA), with the latter occurring in approximately 1% of all adult men2. For men with azoospermia, testicular biopsy is performed to determine whether a blockage is present or whether primary testicular failure is the cause. Recent progress in the treatment of male infertility has enabled the recovery of testicular sperm from NOA patients for intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) to allow these men to father children. However, abnormalities in the genetic conformations that pass through assisted reproductive techniques (ARTs) can have serious implications for the developing zygote. It is therefore essential to determine the underlying genetic basis of male factor infertility to develop appropriate screens for abnormal phenotypes and to find new therapeutic approaches to alleviate human infertility.

Male infertility is estimated to affect approximately 5% of adult men, but 30–40% of the cases are diagnosed as idiopathic because the molecular mechanisms underlying the defects are unknown3,4. There are many well-recognized causes of male infertility, including congenital or developmental defects of the reproductive system, toxin exposure, acquired testicular insult, and genetic anomalies5,6.

Analysis of the genetic factors that affect male infertility will provide valuable insight into the development of targeted treatments for patients and will help to determine the causes of idiopathic infertility. In 2012, a genome-wide association study of Chinese men identified three risk loci for NOA: PRMT6, PEX10, and SOX57. Novel technologies that analyze the influence of genetics from a global perspective may lead to further developments in the understanding of the etiology of male infertility through the identification of specific infertile phenotype signatures, and microarrays are powerful tools for the identification of gene expression profiles of infertile phenotypes. An enhanced understanding of transcription regulation could help geneticists discover how different expression patterns impact a patient's fertility8.

Reproduction is controlled not only by protein-coding genes but also by non-coding regions, including loci that produce small RNAs. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a family of small non-coding RNAs (typically 19–23 nucleotides) that are synthesized from short hairpin precursors and bind to complementary messenger RNAs (mRNAs) to stimulate their degradation or repress their translation. P element wimpy testis-induced (PIWI)-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are distinct from miRNAs in size (approximately 26–31 nucleotides), lack sequence conservation, and have increased complexity. piRNAs form RNA-protein complexes that have been linked to both epigenetic and post-transcriptional gene silencing of retrotransposons and other genetic elements in germ line cells, particularly those involved in spermatogenesis9. miRNAs have critical functions over a wide range of biological and pathological processes, and significant progress has been made to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that regulate spermatogenesis by utilizing miRNAs10. In Dicer-deleted testis, spermatogenesis was retarded at an early stage of proliferation and/or early in differentiation, suggesting that miRNAs may be involved in meiotic gene silencing and that alteration in miRNA expression may be a factor in male infertility11.

In this report, we present an integrative analysis of the gene expression profiling of both mRNAs (Agilent SurePrint G3 Human Gene Expression 8 × 60K Microarray Kit platform) and miRNAs (Agilent Human miRNA Microarray 8 × 60K Release 16.0 platform) in 7 testicular biopsies, including 4 patients with NOA and 3 patients with OA (histological examination showed normal spermatogenesis), to characterize NOA and to identify the specific pathophysiology and molecular pathways of the disease. Then, we validated some of our most interesting findings in the same cohort of NOA patients, and some promising novel correlation signatures of these miRNA/mRNA pairs were discovered. Furthermore, network analysis of the differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs pinpointed key signaling pathways that were frequently disrupted in the investigated NOA patients. Taken together, our data suggest that miRNA/mRNA expression differences between NOA and OA may lead to novel diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Participants

Testicular biopsy specimens for microarray analysis were obtained from 4 patients (aged 28–29 years) with NOA and 3 patients (aged 25–28 years) with OA (see supplement file 1: Patient information.docx). Each patient underwent testicular sperm extraction (TESE) for assisted reproduction and/or diagnostic biopsy for histological examination. Each patient was first diagnosed with azoospermia due to showing no ejaculated spermatozoa in a semen examination. Subsequently, OA was defined as follows: (1) motile spermatozoa sampled from microsurgical epididymal sperm aspirations (MESAs) or (2) a considerable number of mature spermatozoa sampled using TESE. NOA was tentatively defined as having no epididymal and/or testicular spermatozoa. In most patients, the preoperative levels of serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and total testosterone were measured. The infertile male patients who visited the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University received a routine semen examination according to the 1999 WHO criteria. An ideal normal control study population would consist of volunteers of known fertility, but difficulties in acquiring testicular samples makes this impractical. Instead, samples from urology patients who had no history of meiotic defects or infertility and in which histological examination showed normal spermatogenesis were analyzed. In addition, none of the controls were exposed to adjuvant hormonal therapy prior to orchiectomy. The ethics committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University approved the study protocols, and each participant gave written informed consent. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

RNA extraction

Immediately after retrieval, testicular tissues were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual sperm and to normalize the cell composition; the samples were then stored at −80°C until processing. Total RNA, including miRNAs, was isolated using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Catalog no. 217084, Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA concentration, purity and RNA integrity number (RIN) were determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany), an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA 6000 NanoLabChip Kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany), respectively. The inclusion criteria required a minimum RIN ≥ 7.0 for the sample to be acceptable for microarray analysis. Each RNA sample was then divided into two aliquots that were used either for the miRNA microarray or the gene expression microarray.

Gene expression microarray

For microarray hybridization, 100 ng of total RNA was labeled using the Low Input Quick Amp Labeling kit (Agilent 5190-2305) following the manufacturer's instructions and then hybridized to the Agilent SurePrint G3 Human gene expression 8 × 60K microarray according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 100 ng of total RNA was converted to cDNA, followed by in vitro transcription and incorporation of Cy3-CTP into the nascent cRNA. After fragmentation, the labeled cRNA was hybridized to the microarrays for 17 h at 65°C and scanned as described in the manufacturer's protocol. The arrays were washed and scanned on an Agilent G2565CA microarray scanner with a 100% photomultiplier tube (PMT) and 5-μm resolution. The intensity data were extracted using the Feature Extraction 10.7.3.1 Software (Agilent Technologies).

miRNA microarray

Total RNA samples were spiked using the MicroRNA Spike-In Kit (Agilent Technologies) to assess the labeling and hybridization efficiencies. After the spiked total RNA was treated with alkaline calf intestine phosphatase, a labeling reaction was initiated with 100 ng of total RNA per sample. T4 RNA ligase, which incorporates cyanine 3-cytidine biphosphate into the RNA (miRNA Complete Labeling and Hyb Kit; Agilent Technologies), was used to label the dephosphorylated RNA. Cyanine 3-labeled miRNA samples were then prepared for one-color hybridization (miRNA Complete Labeling and Hyb Kit). The labeled miRNA samples were hybridized to human miRNA microarrays (Release 16.0, 8 × 60K format; Agilent Technologies) at 55°C for 20 h, and after washing the microarray slides with buffers of increasing stringency (Gene Expression Wash Buffers; Agilent Technologies), the slides were dried with acetonitrile. The fluorescent signal intensities were then detected on an Agilent Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies) with the Scan Control A.8.4.1 Software (Agilent Technologies) and extracted from the images using the Feature Extraction 10.7.3.1 Software (Agilent Technologies). All of the steps were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microarray data analysis

The gene expression and miRNA microarray raw data were normalized using GeneSpring GX software version 12.0 (Agilent Technologies). The signal values were transformed to the log base 2, and then quantile and percentile shifts were applied to obtain equal distributions of the probe signal intensities. The comparative analysis between the NOA and OA group samples was carried out using the t-test (p-values) and the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (adjusted p-values) using SAM (http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/). Compared with the expression level of the reference RNA, genes and miRNAs were determined to be differentially expressed if the adjusted p-values were < 0.05 and if the fold change (FC) was >2 or <1/2.

GO and KEGG pathway analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway analyses were performed using Cytoscape V2.7 (http://cytoscape.org/) with the ClueGo V1.3 plug-in [11]. ClueGO determines the distribution of the target gene list across the GO terms and pathways. The p-value was calculated using right-sided hypergeometric tests, and Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment was used for multiple test correction. An adjusted p-value<0.05 indicated a statistically significant deviation from the expected distribution, and thus the corresponding GO terms and pathways were enriched in target genes. We analyzed all of the differentially expressed genes using GO and KEGG pathway analyses.

miRNA-mRNA enrichment analysis and negative correlation

Putative target gene sets of differentially expressed miRNAs were predicted using the following algorithms: MiRanda12, Pictar13, TargetScan14, Microrna.org15, PITA16, MicroT17, and RNA2218. The p-values were calculated using right-sided hypergeometric tests, and Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment was used for multiple test correction. An adjusted p-value < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant deviation from the expected distribution. Pearson correlation coefficients between a particular miRNA and its predicted target mRNAs were computed using R (http://www.R-project.org) to determine whether the expression levels of each miRNA and of its mRNA targets were negatively correlated (correlation <0 and Fisher P corrected by FDR <0.05)19. For each miRNA-target found to meet the above-mentioned criteria, we designed a variable theta (θ) to present the strength of the relationship. θ = FC1/FC2, where FC1 means the fold change of the significantly expressed genes, and FC2 means the fold change of the significantly expressed miRNAs; the reciprocal of FC was taken if FC < 0.

Functional Network Analysis

First, TarBase20 was used to compare the experimentally validated miRNA targets to the putative targets. Second, the human protein-protein interaction networks (PPINs) were downloaded from the Human Protein Reference Database21. Finally, the igraph package of the statistical language R was applied for functional profiling, and the network visualization and analysis tool Cytoscape22 was used to find the putative target genes for the predicted miRNAs involved in NOA within the PPINs. In addition, the Markov cluster algorithm23 was used to identify highly connected modules within the global networks.

Hierarchical clustering

Hierarchical clustering was performed using Cluster version 3.0 and Java TreeView version 1.1.6 to identify and visualize patterns within the dataset. With the use of clustering algorithms, the samples and probes were grouped based on similarities in the expression profiles. The probeset was filtered based on the standard deviation to exclude the probes of least variance. The average linkage and median centering were the chosen parameters, and both unsupervised and supervised clustering was used. In the unsupervised method, all genes were included, whereas supervised clustering involved input of significant genes.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for miRNAs

Relative quantitative real time PCR was performed using the miScript PCR System along with the 10 × miScript Primer Assays for hsa-miR-563, hsa-miR-125a-3p, hsa-miR-375, and hsa-miR-521 (Qiagen) were to confirm the array results. The RNU6B snRNA primer assay (Qiagen) was chosen as an endogenous reference for normalization, and all procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for gene expression

To validate the different expression levels of the mRNA genes determined by microarray, qPCR primers were selectively designed for 5 mRNA genes (PLCXD3, SLC1A3, ITPR1, and CMYA5) that were found to be differentially expressed in the discovery screen. GAPDH was selected as the internal control. Two micrograms of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed for cDNA synthesis using a Quanti-Tect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The reverse transcription products were amplified using the TransStar Top Green qPCR Super Mix (TransGen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Results

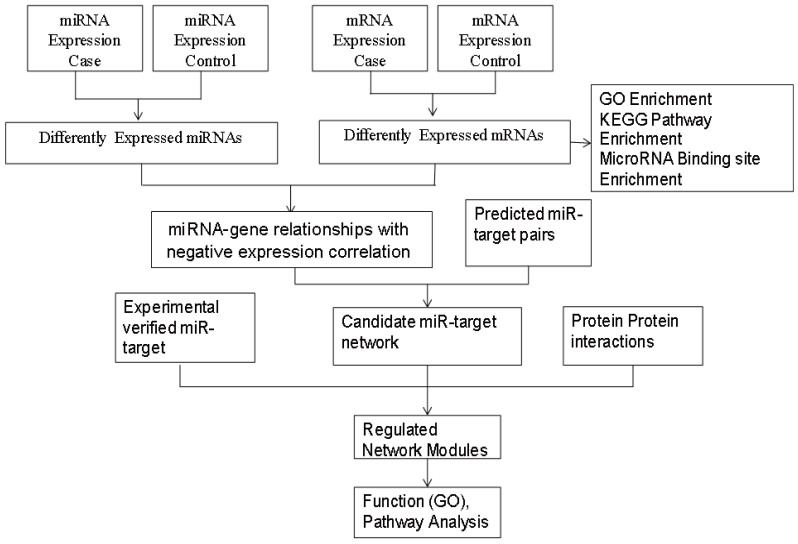

miRNAs regulate mRNA and protein levels by cleavage and/or translation/transcriptional repression of the mRNA in a tissue-specific manner. However, the tissue specificity of miRNA regulation is known only in some specific cases24. We describe a method for identifying direct mRNA targets of miRNAs in NOA that is based on measuring the anti-correlation signal between differentially expressed miRNAs and mRNAs. The stepwise procedure is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the microarray data analysis.

Stage 1: Set threshold values to collect the differentially expressed (upregulated and downregulated) miRNAs and mRNAs. Stage 2: Determine the corresponding GO terms, KEGG pathways and particular miRNAs that are enriched for the target genes. Stage 3: Determine the predicted miRNAs-genes using algorithms and confirm these results using correlation analysis. Stage 4: Integrate the experimentally validated miRNA targets, interacting proteins and predicted miRNAs-genes to build functional networks. Stage 5: Identify highly connected modules within the global networks and then perform GO term and KEGG analyses.

Differentially expressed genes and miRNAs

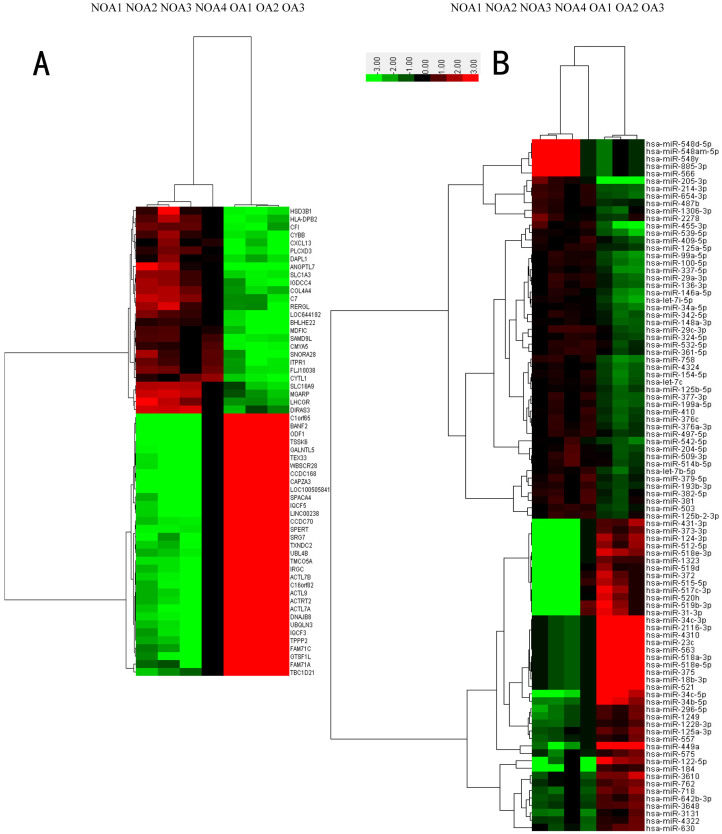

After applying a stringent filtering approach that compared NOA with OA (adjusted p-value < 0.05, fold change > 2 or <1/2), we identified 1944 upregulated and 2768 downregulated genes and 51 upregulated and 42 downregulated miRNAs. Based on some differentially expressed mRNAs and all differentially expressed miRNAs, trees with clear distinctions between OA and NOA patients were generated by cluster analysis (Figure. 2). Figure 2A shows a heat map of the expression of some differentially expressed mRNAs, and Figure 2B shows a heat map of the expression of 93 differentially expressed miRNAs. These results indicate that the gene expression in NOA can be robustly separated from that in OA.

Figure 2. Hierarchical clustering of mRNAs (A) and miRNAs (B) in testicular tissue samples.

Testicular tissue samples were clustered according to the expression profiles of 59 two-fold differentially expressed mRNAs (A) and 93 two-fold differentially expressed miRNAs (B) between 4 NOA patients and 3 OA patients. All samples were properly assigned to the correct class. The key color bar indicates that the mRNA and miRNA expression levels increased from green to red compared to the OA samples (a dark color indicates that the expression level is close to that of OA).

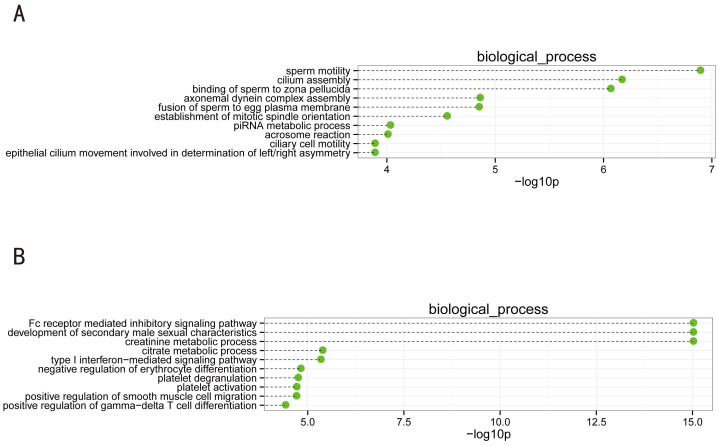

GO enrichment of differentially expressed genes

Eighty-eight GO biological processes (q-values<0.05) were associated with the downregulated genes. As shown in Figure 3A, the top 10 significantly enriched biological processes were as follows: sperm motility, cilium assembly, binding of sperm to zona pellucida, axonemal dynein complex assembly, fusion of sperm to egg plasma membrane, establishment of mitotic spindle orientation, piRNA metabolic process, acrosome reaction, ciliary cell motility, and epithelial cilium movement involved in determination of left/right asymmetry. These biological processes, while not unexpected, are all closely connected with physiological germ cell deficiencies of the testis. Specifically, it appears that the activity of piRNAs in transposon silencing is most important during the development of the mammalian embryo25, and in both Caenorhabditis elegans and humans, piRNAs are necessary for spermatogenesis26.

Figure 3. Top 10 categories of the GO biological processes associated with the significantly downregulated (A) and upregulated genes (B).

Dashed lines represent the p-values for the ten top-ranked categories of GO biological processes associated with the downregulated (upper panel) and upregulated (lower panel) gene lists. The p-values were calculated using hypergeometric tests and corrected by Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment. The p-values are expressed as the negative logarithm (base 10).

The number of GO biological processes (q-values<0.05) associated with the upregulated genes was 585, as shown in Figure 3B. The top 10 significantly enriched biological processes was as follows: Fc receptor-mediated inhibitory signaling pathway, development of secondary male sexual characteristics, creatinine metabolic process, citrate metabolic process, type I interferon-mediated signaling pathway, negative regulation of erythrocyte differentiation, platelet degranulation, platelet activation, positive regulation of smooth muscle cell migration, and positive regulation of gamma-delta T cell differentiation. In males, testosterone stimulates spermatogenesis and influences the development of male secondary sex characteristics. It was demonstrated early on that the mean plasma concentrations and production rates of testosterone were higher in males insensitive to androgen than in normal men27. The cohort of upregulated genes mainly consisted of somatic transcripts that were involved in Sertoli- and Leydig cell function as well as in inflammation. It should be noted that the majority of these somatic genes were not upregulated at all but only displayed enriched mRNA populations because the pool of germ cell RNA from the NOA samples was decreased after extraction28.

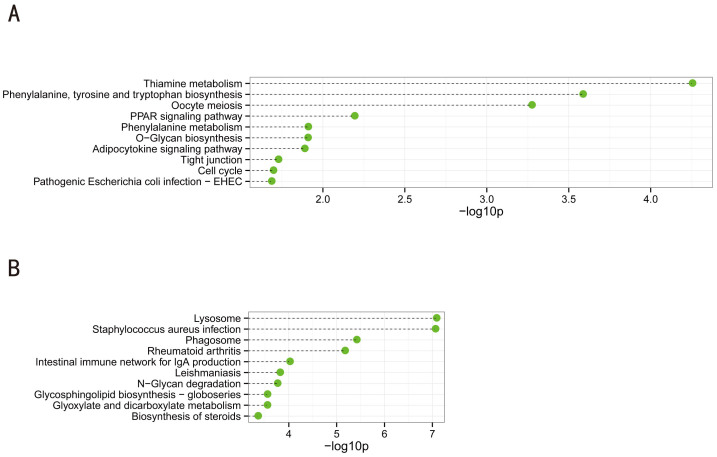

KEGG enrichment of differentially expressed genes

Nineteen KEGG pathways (q values<0.05) were associated with the downregulated genes. As shown in Figure 4A, the top 10 significantly enriched biological processes were as follows: thiamine metabolism; phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis; oocyte meiosis; PPAR signaling pathway; phenylalanine metabolism; O-Glycan biosynthesis; adipocytokine signaling pathway; tight junctions; cell cycle; and pathogenic Escherichia coli infection-EHEC. It is notable that global downregulation of multiple biosynthesis and metabolism pathways might be a characteristic phenotype of NOA, at least when compared with OA.

Figure 4. Top 10 categories of KEGG pathways associated with the significantly downregulated (A) and upregulated genes (B).

Dashed lines represent the p-values for the 10 top-ranked categories of KEGG pathways associated with the downregulated (upper panel) and upregulated (lower panel) gene lists. The p-values were calculated using hypergeometric tests and corrected by Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment. The p-values are expressed as the negative logarithm (base 10).

The number of KEGG pathways (q-values<0.05) that were associated with the upregulated genes was 49, as shown in Figure 4B. The top 10 significantly enriched pathways were as follows: lysosome, Staphylococcus aureus infection, phagosome, rheumatoid arthritis, intestinal immune network for IgA production, leishmaniasis, N-Glycan degradation, glycosphingolipid biosynthesis-globoseries, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism, and biosynthesis of steroids. Interestingly, the lysosome pathway was the most significantly enriched pathway associated with the upregulated genes in NOA, which indicated that perturbation of the normal function of lysosomes might be an important molecular event during spermatogenesis29. Recently, the acrosome was proposed as a novel lysosome-related organelle, which was interesting because the biogenesis of the acrosome shares some components with the lysosomal pathway30.

miRNA enrichment of differentially expressed genes

Based on online database analysis (MiRanda, Pictar, TargetScans, Microrna.org, PITA, MicroT, and RNA22.), 217 miRNAs and 791 miRNAs were significantly enriched in the downregulated and upregulated genes, respectively. Many miRNAs (such as miR-491-3p, miR-302a, miR-520d-3p, and miR-383) that were shown to have altered expression in previous studies31 were also enriched in our study. The top 10 ranked miRNAs are shown in Table 1. As expected, most of the miRNAs were significantly correlated with multiple target genes. We also noticed that a significant number of miRNA families (such as let-7 and let-506) that had not been previously annotated in male infertile studies were enriched in these gene sets.

Table 1. The top 10 enriched regulated miRNAs of the down-regulated genes and up-regulated genes.

| miRNA | Target number | P-value* |

|---|---|---|

| down-regulated genes | ||

| hsa-miR-380 | 93 | 3.28E-06 |

| hsa-miR-30c-1 | 108 | 2.50E-05 |

| hsa-miR-101 | 89 | 9.24E-05 |

| hsa-miR-30c-2 | 107 | 2.02E-04 |

| hsa-miR-99b | 84 | 6.15E-04 |

| hsa-miR-30d | 100 | 6.42E-04 |

| hsa-miR-130b | 69 | 9.99E-04 |

| hsa-miR-33a | 73 | 2.05E-03 |

| hsa-miR-99a | 87 | 2.07E-03 |

| hsa-miR-302d | 91 | 3.52E-03 |

| up-regulated genes | ||

| hsa-miR-548c-3p | 1179 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-186 | 1161 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-511 | 1155 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-432 | 1136 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-9 | 1100 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-590-3p | 1098 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-548n | 1083 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-93 | 1064 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-34a | 1061 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-539 | 1051 | 0 |

*: The p-values was calculated by hypergeometric tests, and corrected by Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment

mRNA-miRNA determination

Pearson correlation analysis was applied to the top 75% variably expressed miRNA and mRNA genes that were found in the microarray analysis. Then, we retained the overlapping, reliable pairs that showed anti-correlated miRNA-mRNA expression and predicted the miRNA target genes. This procedure identified 2461 mRNA targets for the 184 miRNAs. Table 2 shows the top 10 differentially expressed miRNA-target gene relationships. By carefully examining the expression of the individual miRNAs that negatively correlated with the expression levels of their target genes, we found that miR-563 was downregulated and that its predicted target, PLCXD3, a phospholipase that hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids, was upregulated in NOA.

Table 2. The top 10 differently expressed miRNA-target relationships.

| miRNA | Gene Symbol | miRNA FC | Gene FC | θ* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | SPERT | 2.687126 | 0.001624 | 229.0993 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | SPACA4 | 2.687126 | 0.001626 | 228.9134 |

| hsa-let-7c | SPERT | 2.740839 | 0.001624 | 224.6096 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | ACTL7A | 2.687126 | 0.001669 | 222.9788 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | TSSK6 | 2.687126 | 0.001829 | 203.4802 |

| hsa-miR-503 | FAM71C | 2.325835 | 0.002232 | 192.6269 |

| hsa-let-7c | DNAJB8 | 2.740839 | 0.0019 | 192.0028 |

| hsa-let-7c | IRGC | 2.740839 | 0.001922 | 189.8442 |

| hsa-miR-376c | GALNTL5 | 2.570977 | 0.002276 | 170.914 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | UBQLN3 | 2.687126 | 0.002268 | 164.0956 |

*: θ = FC1/FC2, FC1 means fold change of significantly expressed genes, and FC2 means fold change of significantly expressed miRNAs. Take the reciprocal of FC, if FC<0.

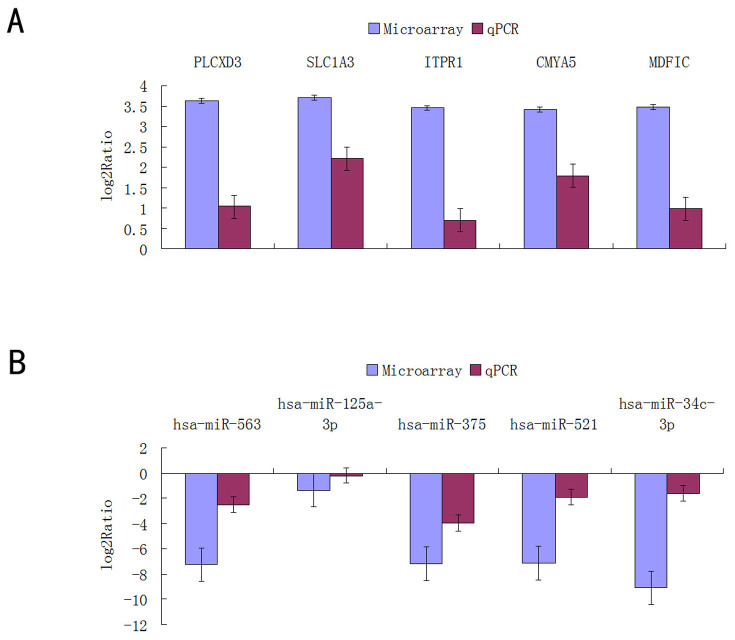

Validation of mRNA and miRNA expression

Subsets of mRNAs (including PLCXD3, MDFIC, SLC1A3, ITPR1, and CMYA5) and miRNAs (including miR-563, miR-375, miR-521, miR-125a-3p, and miR-34c-3p) that were identified to be differentially expressed by microarray analysis were selected for further validation (Figure 5). Real-time RT-PCR was then performed to assess the mRNA and miRNA expression in samples from the same testicular tissues. Comparison of the expression levels between the microarray data and the qPCR results demonstrated a strong correlation between the two platforms. The fold changes in the expression of the tested mRNAs and miRNAs that were determined using qRT-PCR were largely concordant with the microarray data. Melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis was also used to control for the specificity of the qPCR products.

Figure 5. Comparison of the microarray and qPCR results for the mRNA (A) and miRNA genes (B).

Genes determined to be differentially expressed in all of the NOA patients by microarray analysis were validated by qPCR. The height of the columns in the chart represents the log-transformed average fold change in expression across the 4 patients for each of the validated genes; bars represent standard errors.

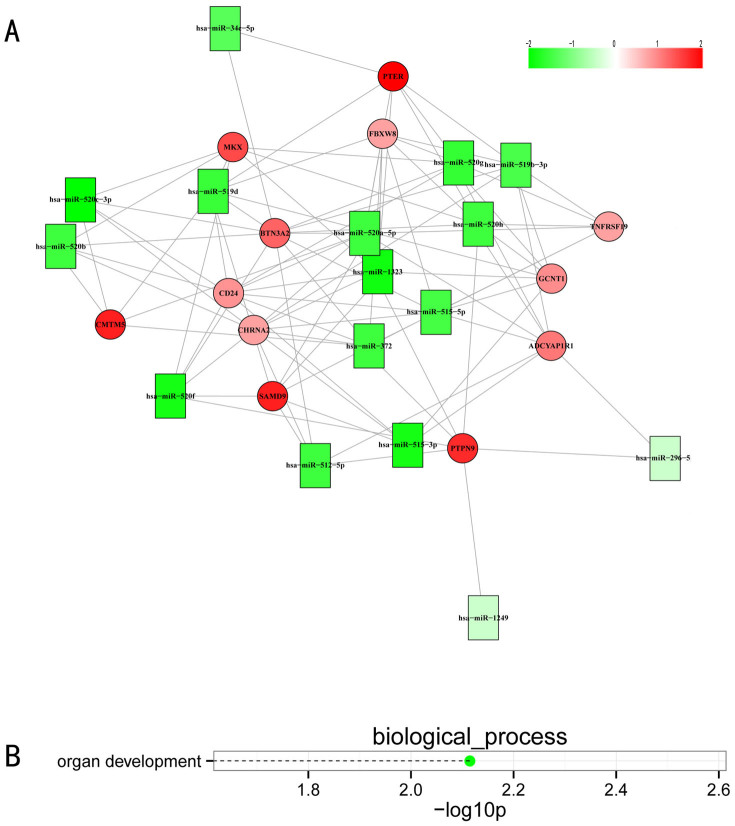

Global miRNA-regulated network integration

Using our identified miRNA-targets, the experimentally validated miRNA targets in TarBase, and the human protein-protein interaction networks (PPINs), we built a global miRNA-regulated network involving 4749 edges (4500 miRNA-targets, 249 PPIs), 2613 coding genes, and 193 miRNAs (see supplement file 2: network.pdf). To further visualize the miRNA-mRNA interactions, we exported the MCL-generated connectivity information to Cytoscape and observed the various degrees of miRNA-mRNA interactions. Figure 6 shows one of observed modules in the global miRNA-regulated networks. Remarkably, we also observed that the gene and miRNA sets of this module were implicated in organ development through GO cell processes that reflected the dysfunction of testicular development.

Figure 6. Visualization of a portion of the miRNA-regulated network (A) and of the involved GO biological processes (B).

Negatively correlated miRNA-mRNA interactions were visualized as a network using Cytoscape. This network gives, for the first time, a theoretical outline of the concerted action of regulating miRNAs and their potential target mRNAs in NOA. Red nodes represent miRNAs, green nodes represent miRNA targets, and the yellow edges represent protein-protein interactions (A). Dashed lines represent p-values for the ten top-ranked GO biological processes of the module (B). The p-values were calculated using hypergeometric tests and corrected by Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment. The p-values are expressed as the negative logarithm (base 10).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the mRNA targets of dysregulated miRNAs using integrated analyses of miRNA and mRNA expression profiling in men with normal versus impaired spermatogenesis. Although putative identification of miRNA-targets using seed sequence complementarity and free energy predictions of miRNA-mRNA duplexes can be achieved using databases such as TargetScan, the false positive rate for such matches is unacceptably high. We have developed and validated a simple method to identify functional mRNA targets of miRNAs in NOA using testicular tissues. When using this method, the subset of anti-correlated miRNA-mRNA pairs are found from a larger set of miRNAs and mRNAs that are differentially expressed in cases and controls. The principal merit of our approach was to reduce the large number of relatively speculative matches that are found when using seed sequences alone to a smaller set of functional, tissue-specific targets. The main issue with this method is that it cannot find targets affected by translation inhibition. For such targets, changes in miRNA levels would not affect the mRNA levels but would reduce the protein levels32.

We investigated the differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs from NOA tissue compared with that from OA tissue using microarray analysis and qRT-PCR. The results of the microarray analysis correlated well with those from qPCR in our study. Recent studies have identified a number of miRNAs that are significantly upregulated in human testis, spermatozoa, and seminal plasma33, and more than 80 genes have been identified as essential for male infertility in humans and mice34. Genes on the Y chromosome have been emphasized because of observed microdeletions in patients; in addition, genes such as DAZ and HSFY, which were also discovered in our results, have been examined as possible susceptibility genes for azoospermia35,36. Our comparative analysis revealed a large number of deregulated genes. In 2014, Nobuyoshi Takasaki et al found that heterozygous mutation of GALNTL5 affected male infertility by impairing sperm motility37, which was shown to be downregulated in our microarray data. Classification of azoospermia in NOA and OA patients based on the expression patterns of key molecular markers may be used for azoospermia diagnosis and prognosis. In addition, many novel miRNA and mRNA candidates were identified in this study and validated by qPCR, which further complements the current catalog of miRNAs expressed in the testis. We identified miR-34c-3p as a member of the conserved miRNA family, miR-34, which has been proven to be structurally similar to miR-449 family members and has been previously shown to be highly enriched and specifically expressed in germ cells38. Integrative analysis of mRNA and miRNA expression profiles facilitated the identification of deregulated biological processes or pathways that might be regulated by miRNAs, which in turn could serve as ideal therapeutic targets39.

We systematically elucidated the miRNA and gene expression profiles of testes of NOA patients and characterized the genetic pathways that were either under-regulated or over-regulated. Systematic comparisons then demonstrated the common physiological changes in the testis of patients with NOA. Molecular processes and signaling pathways controlling cell fates (e.g., cell cycle and apoptosis pathways) and cell communication (e.g., focal adhesion and receptor interaction) were found to be significantly disrupted in NOA, based on microarray analysis. Because spermatogenesis is a complex differentiation process, NOA could result from a defect at any stage of the process. Our results demonstrate that the expression phenotype of NOA testis is characterized by the loss of normal spermatogenesis function and that upregulated expression of mRNA genes results from the downregulated expression of miRNA genes.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study presents the first integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression in NOA. We identified a number of mRNAs and miRNAs that are differentially expressed in NOA and OA. The differentially regulated miRNAs and mRNAs identified in the NOA group compared with the OA group will help us to better understand the mechanisms involved in spermatogenesis and may lay the groundwork for the development of novel biomarkers for male infertility. The main innovation in this paper is that we developed a method to integrate miRNA and mRNA microarray analyses to identify functional mRNA targets of miRNAs with altered expression in NOA testicular tissues.

Author Contributions

X.Z. collected clinical data and signed the testing report of each patient. Z.M.L. drafted the manuscript and analyzed the data. H.N.L. performed the array experiments. L.G. established the qPCR method. Q.L. and Z.X.L. interpreted the results. C.M.T. conceived the study and revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in this study. The research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of China (31171375).

References

- Hirsh A. Male subfertility. BMJ 327, 669–672, 10.1136/bmj.327.7416.669 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduro M. R. & Lamb D. J. Understanding new genetics of male infertility. J Urol 168, 2197–2205, 10.1097/07.ju.0000023290.61978.b2 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghissi K. S. & Wallach E. E. Unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril 39, 5–21 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada A., Esteves S. C., Nizza M. & Agarwal A. Unexplained male infertility: diagnosis and management. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology 38, 576–594 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlin A. et al. Male infertility: role of genetic background. Reprod Biomed Online 14, 734–745 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube E., Hermo L., Chan P. T. & Cyr D. G. Alterations in gene expression in the caput epididymides of nonobstructive azoospermic men. Biol Reprod 78, 342–351, 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062760 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z. et al. A genome-wide association study in Chinese men identifies three risk loci for non-obstructive azoospermia. Nat Genet 44, 183–186, 10.1038/ng.1040 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P. J. et al. Coordinated transcriptional regulation patterns associated with infertility phenotypes in men. J Med Genet 44, 498–508, 10.1136/jmg.2007.049650 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi M. C., Sato K., Pezic D. & Aravin A. A. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12, 246–258, 10.1038/nrm3089 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Kokkinaki M., Pant D., Gallicano G. I. & Dym M. Small RNA molecules in the regulation of spermatogenesis. Reproduction 137, 901–911, 10.1530/REP-08-0494 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K. et al. MicroRNA biogenesis is required for mouse primordial germ cell development and spermatogenesis. PLoS One 3, e1738, 10.1371/journal.pone.0001738 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betel D., Wilson M., Gabow A., Marks D. S. & Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res 36, D149–153, 10.1093/nar/gkm995 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek A. et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet 37, 495–500, 10.1038/ng1536 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. P., Burge C. B. & Bartel D. P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20, 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maragkakis M. et al. Accurate microRNA target prediction correlates with protein repression levels. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 295, 10.1186/1471-2105-10-295 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz M., Iovino N., Unnerstall U., Gaul U. & Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet 39, 1278–1284, 10.1038/ng2135 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maragkakis M. et al. DIANA-microT web server: elucidating microRNA functions through target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 37, W273–276, 10.1093/nar/gkp292(2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda K. C. et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell 126, 1203–1217, 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansson R. et al. Pearson correlation analysis of microarray data allows for the identification of genetic targets for early B-cell factor. The Journal of biological chemistry 279, 17905–17913, 10.1074/jbc.M400589200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethupathy P., Corda B. & Hatzigeorgiou A. G. TarBase: A comprehensive database of experimentally supported animal microRNA targets. RNA 12, 192–197, 10.1261/rna.2239606 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshava Prasad T. S. et al. Human Protein Reference Database--2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res 37, D767–772, 10.1093/nar/gkn892 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13, 2498–2504, 10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluccio A., Loebl M. & Vondrak J. New algorithm for the Ising problem: partition function for finite lattice graphs. Phys Rev Lett 84, 5924–5927 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R., Calin G. A. & Croce C. M. MicroRNAs in Cancer. Annu Rev Med 60, 167–179, 10.1146/annurev.med.59.053006.104707 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin A. A. et al. A piRNA pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA methylation in mice. Mol Cell 31, 785–799, 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.003 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. & Reinke V. A C. elegans Piwi, PRG-1, regulates 21U-RNAs during spermatogenesis. Curr Biol 18, 861–867, 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.009 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiman J., Griffin J. E., Gazak J. M., Wilson J. D. & MacDonald P. C. Androgen insensitivity as a cause of infertility in otherwise normal men. N Engl J Med 300, 223–227, 10.1056/NEJM197902013000503 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappallo-Obermann H., Feig C., Schulze W. & Spiess A. N. Fold-change correction values for testicular somatic transcripts in gene expression studies of human spermatogenesis. Human reproduction 28, 590–598, 10.1093/humrep/des433 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Males J. L. & Turkington R. W. Hormonal control of lysosomal enzymes during spermatogenesis in the rat. Endocrinology 88, 578–588 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berruti G., Ripolone M. & Ceriani M. USP8, a regulator of endosomal sorting, is involved in mouse acrosome biogenesis through interaction with the spermatid ESCRT-0 complex and microtubules. Biol Reprod 82, 930–939, 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081679 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J. et al. Altered microRNA expression in patients with non-obstructive azoospermia. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 7, 13, 10.1186/1477-7827-7-13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. et al. Identifying mRNA targets of microRNA dysregulated in cancer: with application to clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. BMC Syst Biol 4, 51, 10.1186/1752-0509-4-51 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Halima M. et al. Altered microRNA expression profiles of human spermatozoa in patients with different spermatogenic impairments. Fertil Steril 99, 1249–1255 e1216 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.054 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk M. M. & Lamb D. J. Genetic dissection of mammalian fertility pathways. Nat Cell Biol 4 Suppl s41–49, 10.1038/ncb-nm-fertilityS41 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmulewicz M. N., Ruiz L. M., Reategui E. P., Hussini S. & Herrera R. J. Single-nucleotide variant in multiple copies of a deleted in azoospermia (DAZ) sequence - a human Y chromosome quantitative polymorphism. Hum Hered 53, 8–17, doi: 48599 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinci G. et al. A deletion of a novel heat shock gene on the Y chromosome associated with azoospermia. Mol Hum Reprod 11, 295–298, 10.1093/molehr/gah153 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasaki N. et al. A heterozygous mutation of GALNTL5 affects male infertility with impairment of sperm motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 1120–1125, 10.1073/pnas.1310777111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhallier F. et al. Role of miR-34c microRNA in the late steps of spermatogenesis. RNA 16, 720–731, 10.1261/rna.1963810 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Sall A. & Yang D. MicroRNA: An emerging therapeutic target and intervention tool. Int J Mol Sci 9, 978–999, 10.3390/ijms9060978 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]