Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to implement self-care support for leg lymphedema patients using mobile phones and to investigate the effects thereof.

Patients and Methods: A total of 30 patients with lymphedema following female genital cancer surgery (stages I to II) who were referred from a nearby gynecologist were randomly divided into groups for routine self-care support (control group) and mobile telephone-assisted support (intervention group) and received the self-care support appropriate to their group. The (total) circumference of the leg with edema, FACT-G (cancer patient QOL), MHP (mental health status), and self-care self-assessment were comparatively investigated at three months after the initial interview.

Results: No significant reduction in the (total) circumferences of legs with edema was confirmed in either the control or intervention group. The intervention group was significantly better than the control group in terms of the activity circumstances and FACT-G mental status at three months after the initial interview. The intervention group was also significantly better in psychological, social, and physical items in the MHP. The intervention group was significantly better than the control group in terms of circumstances of self-care implementation at three months after the initial interview. Additionally, comparison of the circumstances of implementation for different aspects of self-care content showed that the intervention group was significantly better at selecting shoes, observing edema, moisturizing, self-drainage, wearing compression garments, and implementing bandaging.

Conclusion: Compared with routine self-care support, mobile telephone-assisted support is suggested to be effective for leg lymphedema patients’ QOL and mental health status as well as their self-care behaviors.

Keywords: leg lymphedema, self-care, after the surgery of the female genital cancer, mobile telephone-assisted support

Introduction

Lymphedema is a general term for swelling caused by lymphatic vessel dysfunction. Failure to maintain proper care significantly lowers quality of life (QOL), as activities of daily living will be impaired by swelling in the extremities. Body image is also adversely affected, causing a considerable psychological impact. In Japan, as many as 150,000 patients suffer from lymphedema; the most common cause is lymph node dissection associated with malignant tumor removal1).

Training of therapists in lymphedema treatment in Japan was initiated approximately 10 years ago. In 2007, the fees for lymphedema guidance and management after cancer surgery became eligible for medical cost compensation. Recognition of the importance of lymphedema care has gradually become more widespread.

What matters most for patients with lymphedema is daily self-care1, 2). Previous research has also studied educational endeavors in establishing self-care3,4,5,6). Experience from implementing self-care consultations for lymphedema, however, has led to the perception that establishing self-care behaviors requires more than just education and guidance in terms of knowledge and technology. A system of self-care support with which patient needs can be handled in a timely and continuous manner is considered necessary, but research on supporting lymphedema self-care is nowhere to be found, either domestically or abroad.

For patients with lower-limb lymphedema, it is important but quite difficult to keep the lower limbs at rest during activities of daily living. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct training specifically tailored to an individual patient’s daily life on a case-by-case basis. However, in patients with lower-limb lymphedema, the volume and weight of the lower limbs increase, making movement difficult and leading to a great burden on patients treated at medical facilities. Therefore, for patients with lower-limb lymphedema, it is difficult to receive frequent care and support from specialists. As controlling the symptoms of lower-limb lymphedema is more challenging compared with controlling those of upper-limb lymphedema, it is not surprising that many patients with lower-limb lymphedema develop serious complications such as elephantiasis or lymphorrhea.

This has led attention to be focused on the use of mobile phones. According to research by Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the mobile phone adoption rate exceeded one unit per person by the end of March 2012, and the number of contracts amounts to 100.1% of the population. In the clinical field, there is a research report related to the construction of a system for supporting self-management of blood glucose in diabetic patients using mobile phones7) and one on the effects of nursing intervention using mobile phones for high-anxiety diabetic patients in the insulin introduction stage8). However, there are no reports on the effects of mobile phone use for supporting self-care of lymphedema patients.

Therefore, I focused on leg lymphedema patients, who are especially burdened by hospital visitation, and investigated the effects of self-care support employing mobile phones.

This study aimed to implement and investigate the effects of self-care support using mobile phones for leg lymphedema patients.

Research Methods

Study design

This study used an association-verifying design incorporated qualitative data in a part.

Operational definitions of terminology

1) Routine support of self-care

Patients received guidance for matters subject to assessment in lymphedema guidance management (mechanism of lymphedema onset/complications/observation points/matters of note in daily living/skin care/drainage/compression/exercise) in face-to-face meetings with qualified lymphatic drainage personnel. This included aspects of support received by both the intervention and control groups equally.

2) Mobile phone-assisted support

Once every two weeks, qualified lymphatic drainage personnel used the video, text, and voice functions of mobile phones to respond to consultations for self-care (mechanism of lymphedema onset/complications/observation points/matters of note in daily living/skin care/drainage/compression/exercise). This included aspects of support received by the intervention group in addition to routine self-care support.

Study subjects

1) Study subject selection criteria

The study subjects were patients referred by a gynecologist working in a nearby research cooperation facility; all subjects gave informed consent and met all of the following criteria:

-

(1)

Postoperative female genital cancer patients who were diagnosed with lymphedema by a physician

-

(2)

Patients who did not have venous diseases such as deep vein thrombosis (acute) or chronic venous incompetency or other cardiovascular diseases and were deemed by a physician to not be at risk in the implementation of lymphatic drainage

-

(3)

Patients with leg lymphedema stage I to II (early) who were deemed safe for support by mobile phone

-

(4)

Patients aged 20–69 who used a mobile phone on a daily basis and were considered able to handle mobile phone communication without difficulty

2) Required number of samples

Based on an effect size of 0.75, α error probability of 5%, β error probability of 20%, and statistical power of 80%, as used in previous research, the required number of subjects for two groups was 28.5. Taking dropout into consideration, the target was set to 30 subjects9).

Survey items and assessment indicators

1) Basic attributes were age, name of primary disease, therapies for female genital cancer, time since edema onset, site of edema, edema staging, and presence or absence of a history of cellulitis.

2) Self-care was assessed by evaluating the following four items

-

(1)

Circumference: With the legs relaxed in the supine position, data were collected for the total circumference from three points, that is, 2 cm above the medial malleolus of the ankle, 10 cm below the lower pole of the patella, and 10 cm above the upper pole of the patella. In cases in which edema appeared in both legs, data were collected where the edema was stronger.

-

(2)

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G): There were 29 items (subscales: 7 items about physical aspects, 9 items about social/family aspects, 6 items about psychological aspects, and 7 items about functional aspects) on the employed cancer patient QOL scale. Subscales were subject to assessment, and reliability and validity were confirmed.

QOL was understood to be higher when the total score was lower in physical and mental aspects and when the total score was higher in social/family aspects and activity circumstances.

-

(3)

Mental Health Pattern (MHP) testing: Reliability and validity were confirmed using a mental health scale composed of a stress score and quality of life (QOL) scale; the mental health scale 8 subscales (a total of 40 items).

In the present study, only the stress subscale (10 items each about physical/psychological/social aspects) was used because QOL was measured with the FACT-G.

In the MHP testing, the higher the score, the higher the stress level.

-

(4)

Self-care check list: An independently created assessment scale was used. Ten the importance of items about important aspects of self-care were assessed using responses of “seldom” (1 point), “about once or twice a week” (2 points), “about 3 to 5 times a week” (3 points), and “Almost daily” (4 points), and total score was calculated. Self-care items were examined by multiple lymphedema care experts to ensure content validity. Cronbach’s α coefficient, which is indicative of reliability, was 0.82.

3) Mobile phone recording (intervention group only)

-

(1)

Photos and video recordings: Images relating to items such as skin condition and status of self-care implementation were transmitted using the mobile phones’ camera functions (Figure 1: mobile phone images during pre-testing).

-

(2)

Communication recording: Conversations were recorded using the mobile phones.

Figure 1.

Mobile phone images during pre-testing

Data collection method

1) Data collection field

Data were collected in the lymphedema consultation room at University B.

2) Data collection period

Data were collected from April 2010 to November 2012.

3) Data collection method

-

(1)

Method of allocation for intervention/control groups

Subjects were allocated randomly, five people at a time in order of arrival, into a control group that received only routine self-care support and an intervention group that received mobile phone-assisted support in addition to routine self-care support.

-

(2)

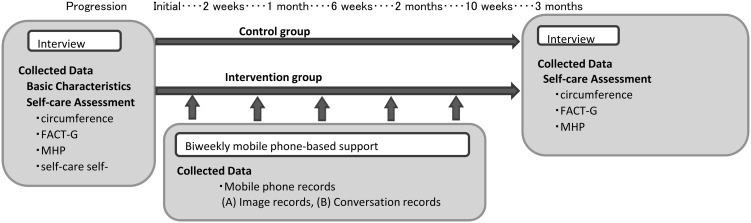

Data collection procedures (Figure 2: protocol)

All intervention and data collection were implemented by one nurse with qualified as a lymphatic therapist in line with the appropriate protocols.

Other than the mobile phone-assisted support, the control and intervention groups received identical support. The data collection time was determined for every patient with the aim of keeping the external edema factors constant, and data were collected at identical intervals. In principle, visitation for outpatient lymphedema care was avoided until three months of data were collected after the initial interview.

-

(3)

Specific method of support for the intervention group

Routine self-care support was implemented at the first interview and at another interview three months later. The content and methods of routine self-care support were identical between the control and intervention groups.

In the intervention group, routine self-care support was accompanied by mobile phone conversations once every two weeks, through which support was provided with the aims of [1] symptom control and psychological intervention through the timely provision of specific knowledge, [2] image-assisted confirmation of skin condition and status of self-care implementation, [3] establishment of a trusting relationship through frequent support, and [4] implementation of a support method that does not create a burden on the legs and can be carried out when it is convenient without the patient having to leave home.

Mobile phone models auIC001V12 were used for mobile phone support and were obtained under a corporate contract. At the first interview, patients were told that the phones were being loaned and could be used any time support was desired, that they would be contacted by the investigator every two weeks in the event that no contact was made by the patient, and that the investigator would cover all mobile phone communication costs.

Figure 2.

Protocol

Method of data analysis

Patients’ basic attributes was subjected to descriptive statistical processing.

Survey items were compared between the intervention group’s first interview and the interview three months later to study whether intervention provided any improvement (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test). Each of the assessment items was also compared between the control and intervention groups to study the effects of the intervention using mobile phones (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test). SPSS (Ver. 13 Windows) was used as the statistical analysis software with the level of significance set to 5%.

Regarding the mobile phone-assisted intervention, content relevant to a “patient’s thoughts during continuing self-care (patient remarks)” and “self-care support content (nurse remarks)” was extracted and encoded from “call recordings” of call content; anything similar was collected and subcategorized, and further similar content was collected, abstracted, and categorized.

Ethical considerations

Because of the possibility that mobile phone operation could cause users stress, the present study was committed to selecting subjects who used mobile phones on a daily basis and to preventing immediate cessation of mobile phone use in the event of stress. The research significance, objectives, methods, predicted results, and risks were fully explained to the research subjects in writing; participation was voluntary, and patients were reassured that lack of consent to participate would not engender prejudicial treatment and that, even if they consented to participate, they could still withdraw without any prejudice. Collected data were encoded and stored on a USB memory stick, which was then kept under lock and key. Measures to ensure proper security in performance of all analyses were also taken, including the use of a computer not connected to the Internet. The study received the approval of the ethics review committee of the University of Shiga Prefecture (No. 144, No. 144-2).

Results

Basic attributes of the subjects (Table 1: basic characteristics of subjects)

Table 1. Basic characteristics of subjects.

| Control group (n) | Intervention group (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 40 years | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 40 to less than 50 years | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| 50 to less than 60 years | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 60 to less than 70 years | 7 | 8 | 15 | |

| Primary disease | Cervical cancer | 15 | 15 | 30 |

| Surgical method | Radical hysterectomy | 14 | 13 | 27 |

| Simple hysterectomy + lymphadenectomy | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Radiation therapy | Yes | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| No | 5 | 7 | 12 | |

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| No | 12 | 12 | 24 | |

| Location of edema | Right leg | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Left leg | 7 | 9 | 16 | |

| Both legs | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Duration of edema | Less than 1 year | 9 | 8 | 17 |

| 1 year to less than 2 years | 5 | 6 | 11 | |

| 2 year to less than 4 years | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Disease stage of edema | Stage I | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Stage II (early) | 12 | 13 | 25 | |

| History of cellulitis | Yes | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| No | 11 | 11 | 22 | |

| Working 20 hours or more/week | Yes | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| No | 12 | 13 | 25 | |

| Living with dependents and dependent children (preschool children) | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| No | 14 | 13 | 27 | |

A total of 31 subjects participated, all of whom were women. One member of the control group developed cellulitis and required frequent support, so she was excluded from the study. Ultimately, there were 15 people each in the control and intervention groups.

No significant difference was noted between the control and intervention groups in terms of basic attributes, and the groups were deemed to be homogenous.

Mobile phone-assisted support entailed a total of five phone calls with each patient over three months. In no instance were there any unscheduled phone calls from patients, and all calls originated from the investigator. In addition, video calls, which were supplementary functions of the selected mobile phones, were not used; phone-assisted support was provided using the phones’ voice call functions only.

Changes over time

1) Comparison between the first interview and interview three months later (Table 2: intergroup comparison of self-care assessment).

Table 2. Intergroup comparison of self-care assessment.

| Control | Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial interview | 3 months later | Initial interview | 3 months later | |||

| median (lowest to highest) |

median (lowest to highest) |

median (lowest to highest) |

median (lowest to highest) |

|||

| Sum total circumference (total value) cm | 109.4 (89.6~126.0) |

1086 (89.4~127.5) |

100.2 (90.0~128.8) |

97.0 (91.6~130.0) |

||

| FACT-G | Physical symptoms | 7 (1~18) |

7 (1~18) |

10 (3~19) |

7* (1~13) |

|

| Social/familial relations | 19 (9~30) |

18 (9~30) |

18 (8~27) |

18 (10~26) |

||

| Psychological state | 11 (2~19) |

10 (2~18) |

9 (3~18) |

6*** (3~12) |

||

| Activity conditions | 14 (12~18) |

16* (14~18) |

14 (10~19) |

20*** (15~23) |

||

| MHP | Psychological | 19 (15~24) |

19 (13~25) |

18 (15~26) |

16*** (10~21) |

|

| Social | 19 (15~23) |

19 (13~22) |

18 (11~25) |

15*** (10~22) |

||

| Physical | 23 (15~28) |

23 (16~28) |

24 (17~33) |

18*** (13~26) |

||

| Total SCL score | 63 (50~71) |

61* (48~66) |

58 (49~84) |

50*** (40~66) |

||

| Self-care self-assessment | 19 (17~23) |

25*** (21~28) |

19 (18~21) |

37*** (28~40) |

||

Wilcoxon signed rank test. Asterisks denote significant differences from the Initial inverview: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

Control group: No significant difference was observed before or after routine self-care support in terms of the circumferences (total) of legs with edema. However, the circumstances of activities, a subscale of the FACT-G, were significantly higher after routine self-care support (P < 0.05), and routine support was shown to be effective for circumstances of activities, a constituent element of QOL. The total score on the stress scale in the MHP was also significantly lower after routine self-care support (P < 0.05), demonstrating that routine support has a stress-relaxing effect. The total score of the self-care check list was significantly higher after routine self-care support (P < 0.005), and routine care was demonstrated to be effective in improving the circumstances of self-care implementation.

Intervention group: The circumferences (total) of legs with edema did not exhibit a significant difference before or after the intervention. However, physical symptoms and mental condition were significantly reduced in the FACT-G at P < 0.01 and P < 0.005, respectively, and circumstances of activity also presented a clear significant difference at P < 0.005. This demonstrates that patient QOL in leg lymphedema is improved by mobile phone-assisted support. Looking closer at the MHP, the psychological, social, physical, and stress score totals each demonstrated significant differences before and after the intervention at P < 0.005, revealing that mobile phone-assisted support has an effect in improving the state of mental health. The total score of the self-care check list also showed a significant difference at P < 0.005, and mobile phone-assisted support was found to improve the circumstances of self-care implementation.

Between-group comparison of the control and intervention groups (Tables 3 and 4)

Table 3. Intergroup comparison of self-care assessment (3 months after support).

| Control group | Intervention group | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (lowest to highest) | Median (lowest to highest) | ||||

| Sum total circumference (total value) cm | 108.6 (89.4~127.5) | 97.0 (91.6~130.0) | |||

| FACT-G | Physical symptoms | 7 ( 1~18) | 7 ( 1~13) | ||

| Social/familial relations | 18 ( 9~30) | 18 (10~26) | |||

| Psychological state | 10 ( 2~18) | 6 ( 3~12) | * | ||

| Activity conditions | 16 (14~18) | 20 (15~23) | *** | ||

| MHP | Psychological | 19 (13~25) | 16 (10~21) | * | |

| Social | 19 (13~22) | 15 (10~22) | * | ||

| Physical | 23 (16~28) | 18 (13~26) | * | ||

| Total SCL score | 61 (48~66) | 50 (40~66) | *** | ||

| Self-care check list | 25 (21~28) | 37 (28~40) | *** | ||

Wilcoxon signed rank test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

Table 4. Intergroup comparison for each self-care check item (3 months after support).

| Self-care check item | Control group | Intervention group | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (lowest to highest) | Median (lowest to highest) | |||

| Selecting clothes | 2 (1~4) | 4 (1~4) | ||

| Selecting shoes | 1 (1~4) | 4 (1~4) | *** | |

| Lower limb elevation | 3 (2~4) | 4 (2~4) | ||

| Observation of edema | 4 (1~4) | 4 (2~4) | ** | |

| Cleanliness of skin | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | ||

| Maintenance of skin | 4 (1~4) | 4 (4) | ||

| Moisturization | 4 (2~4) | 4 (4) | ** | |

| Self-drainage | 2 (1~4) | 4 (4) | *** | |

| Elastic clothing | 1 (1~4) | 4 (2~4) | *** | |

| Bandage | 1 (1) | 3 (1~4) | *** |

Wilcoxon signed rank test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

Comparison the control group, which only received routine self-care support, and the intervention group, which received mobile phone-assisted support in addition to routine self-care support, showed that the intervention group had a significantly lower (P < 0.05) mental condition in the FACT-G at three months after the start of support and had significantly higher (P < 0.005) circumstances of activities. In the MHP, too, the intervention group had lower scores (P < 0.05) for psychological, social, and physical items, while the stress score totals were also significantly different in the intervention group (P < 0.005).

Looking at circumstances of self-care implementation, a significant improvement was noted in the intervention group compared with the control group (P < 0.005). Comparison of the circumstances of implementation for the different forms of self-care at three months after the start of support also showed that, though there was no significant difference between the control and intervention groups for the four items consisting of choosing clothing, raising the legs, and cleaning and protecting skin affected by lymphedema, significant differences were observed in selection of shoes (P < 0.01), observation of edema (P < 0.005), moisturizing (P < 0.01), self-drainage (P < 0.005), use of compression garments (P < 0.005), and implementation of bandaging (P < 0.005).

Mobile phone recordings (intervention group) (Table 5: Feelings of patients continuing self-care (records of patient remarks))

Table 5. Feelings of patients continuing self-care (records of patient remarks).

| Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|

| Anxiety towards physical symptoms | Anxiety towards exacerbation |

| Symptoms concomitant with edema | |

| Circumstances preventing self-care | Cannot make the time |

| Feeling tired and troublesome | |

| Difficulty in long-term exposure of skin | |

| Cannot maintain motivations | |

| Desire to be praised or reprimanded | Wanting to make a good report |

| Desire to pull oneself together through harsh words | |

| Stabilization of symptoms due to self-care | Habituation of self-care |

| Self-awareness of the effects of care | |

| Expectation towards recovery and irritation towards unchanging conditions | Expectation for further effects by strengthening the pressure applied by bandages |

| Days of no change after working/trying hard | |

| Anxiety towards life activities with lymphadenoma | Anxiety towards participating in non-routine activities |

| Anxiety towards living normally | |

| Feels like my feet are heavy | Loss of desire to go out if the legs feel heavy |

| Household chores still need to be done even if the legs feel heavy | |

| Feeling that people will not understand the hardships | |

| Sadness towards isolation | |

1) Patient’s thoughts during continuing self-care (patient remarks)

Patient remarks extracted from the call recordings were analyzed, the results of which yielded 92 codes, and 18 subcategories classified under similar semantic contents and representative of “patient’s thoughts during continuing self-care” were generated and further classified into the 7 categories (Table 4) described below. The punctuation marks « », < >, and “ ” are used for categories, subcategories, and characteristic codes, respectively.

«Physical symptoms and anxieties associated with symptoms»

This category included circumstances in which a patient anticipated the onset or worsening of the symptoms associated with edema and grow increasingly anxious; it was composed of the two subcategories of <symptoms associated with edema> and <anxiety toward worsening>. The records included the states of becoming aware of changes in symptoms in the form of remarks such as “intensified swelling of the ankle”, “red spot, for one”, and “things could get bad if I stop self-care.”

«Circumstances that do not enable self-care»

This category included records relating to circumstances in which self-care was not possible because of family or mood despite the perceived need to continue with self-care. It had four subcategories, <cannot find the time>, <fatigue, finding it a hassle>, <difficult to have one’s skin exposed for a long time>, and<motivation lost>. The records addressed “mother-in-law requires substantial care,” “One hour of massage is impossible, too long,” and “impossibly cold season” among other difficulties of continuing lymphedema self-care, which may not result in healing during day-to-day life.

«Feeling of deserving praise/reprimand»

This category was related to feedback from others and consisted of two categories, <want to have good reporting> and <harsh words make me want to fix things>. The records included such feelings as “I did my best last night, because I want to have good reporting.”

«Symptom stability provided by self-care»

This category was related to circumstances in which patients’ continued to have their own care-stabilized symptoms and consisted of two subcategories, <making self-care a habit> and <being aware of care’s effects>. The records addressed becoming aware of the effects of self-care in the form of remarks such as “drainage provides relief,” and “feeling of tension is gone” by incorporating self-care into daily life and making continuous efforts, as shown by remarks such as “Every day, getting out of the bathtub is followed by drainage, bandaging, and stretching exercises” and “In the bathtub, I practice shoulder turning and abdominal breathing and perform drainage while I wash my body.”

«Expectation for recovery and frustration when it does not occur»

This category was related to the feeling of redoubling one’s efforts for hoped-for improvement upon becoming aware of recovery thanks to continued self-care only to end up feeling it was futile when it was not effective. It comprised the two subcategories of <intensifying the bandage pressure and expecting it to provide greater effect> and <day after day, I try and try, and it does not change>. The records addressed the desire for and disappointment in recovery, as shown by remarks such as “seems like applying more pressure should be thinning” and “no matter how hard I try, there is no major change.”

«Anxiety toward life behaviors when faced with lymphedema»

This category was related to circumstances of feeling lost and worried about how to handle behaviors that were effortless in the absence of edema, such as domestic work, travel, and special cultural or social events. It consisted of the subcategories of <anxiety about participating in events that are not day-to-day> and <anxiety about living life as usual>, and the record addressed doubts and anxieties such as “Will I be able to sit with my legs under a Japanese kotatsu?” and “My stockings bite into the back of my knee; can I continue to wear them?”

«Feels like my feet are heavy»

This category was comprised of the subcategories of <heavy feet make me not want to go out>, <having heavy feet doesn’t mean the housework stops>, <the suffering is something other people won’t understand>, and <isolated loneliness> and contained records relating to circumstances in which foot-related suffering and state of mind were linked. The records included remarks such as “I stop going out when my feet are in a bad condition,” “Even when my feet are in a bad condition, my family does not help me around the house,” “shocked, remarking that I’m lying down yet again,” and “Friends and family are unable to understand my lymph.”

2) Self-care support content (nurse remarks) (Table 6: Details of self-care support (records of nurse remarks))

Table 6. Details of self-care support (records of nurse remarks).

| Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|

| Confirmation of self-care | Observation, skin-care, drainage, pressure |

| Care during daily living | |

| Support and admiration for working hard | Wow! You’re doing great! |

| Resting the body does not signify laziness | |

| Don’t have to try so hard | |

| Sharing the joys of recovery | Confirmation of the importance of maintenance |

| Sharing the joy of being able to go out or participate in hobbies | |

| Sympathy for struggles due to the edema and feeling disconsolate | It must be difficult |

| Acceptance of not being able to perform self-care | It is normal that sometimes you are unable to [care for yourself] |

| It is okay as long as you can come back to self-care | |

| Confirmation of warning signs and support during appropriate management | Proof of tiredness if there is some tension |

| Red rashes and fevers are dangerous | |

| Try to be sensitive to sensations that cannot be expressed by words | |

The content of mobile phone-assisted support found in the call records was analyzed, yielding 56 codes. A total of 13 subcategories classified under similar semantic content and representative of “self-care support” were generated and further classified into 6 categories (Table 5). Categories relating to self-care support are described below. As with the patient thoughts during continuing self-care, the punctuation marks « », < >, and “ ” are used for categories, subcategories, and characteristic codes, respectively.

«Confirmation of self-care»

This category included records relating to confirmation of circumstances of self-care implementation and comprised the two subcategories of <observation, skin care, drainage, compression> and <careful attention in daily life>. It contained information about checks regarding the circumstances of self-care implementation, such as checks for “dryness or lack thereof” and “applying moisturizer cream,” along with records of remarks in which careful attention in daily life was prompted, as shown by remarks such as “slightly lifting the feet when lying down” and “I wear sneakers as much as possible when it is not necessary.”

«Admiration and support for when great efforts are made»

This category comprised the three subcategories of <Wow! You’re doing so well!>, <Giving your body some rest does not mean you are lazy>, and <There’s no need to overwork yourself>. The records included remarks concerning support efforts made when working hard to continue self-care, such as “You have been working hard” and “Giving your body some rest does not mean you are lazy.”

«Sharing the joy of recovery»

This category comprised the two subcategories of <confirming the importance of successfully maintaining recovery> and <sharing the joy of being able to go out and do what one likes>. The records included remarks concerning the joy of sharing with the patient the circumstances in which self-care implementation had alleviated symptoms and broadened the available range of activities, such as “had a great time at a hot spring with family” and “I grew tomatoes in the garden.”

«Sympathizing with the suffering and helplessness that come with edema»

This category comprises the subcategory of <I know it’s painful; I know it’s hard>, and the records included remarks related to being supportive in the face of the suffering and hardship of living with lymphedema, such as “Having heavy feet is burdensome. How are you holding up?”

«Accepting when self-care is not possible»

This category comprised the two subcategories of <It’s not unusual for it to not always be possible> and <A return to self-care would be good>. It consisted of records concerning accepting and providing encouragement with respect to patients’ unsuccessful circumstances in the form of remarks such as “It’s OK for there to be some days when it isn’t possible” in patients who had complained of the inability to continue self-care for various reasons and records related to prompting patients to regain a position that would allow them to return to self-care, as shown by remarks such as “The fact that some days it is not possible does not mean there won’t be days where you try hard. It’s OK.”

«Confirmation of dangerous signs and corresponding advice»

This category comprised the three subcategories of <A feeling of tension is evidence that you are tired>, <Breaking out in a red rash and feeling hot is dangerous>, and <Be sensitive to the feelings that you are unable to voice>. It consisted of records about confirming dangerous signs associated with edema including remarks such as “The feeling of tension is a bodily sign only you yourself can know,” “guidance on how to rest and stay cool,” and “Are you tired?” These provide information about how to handle them and give advice on the appropriate measures to take.

Discussion

No significant difference in the total circumference of the diseased leg was confirmed between the mobile phone-support group (intervention) and the self-care support group (control) three months after the first interview. However, mobile phone support was found to be effective in improving QOL for lymphedema patients, assessing psychological states, and supporting self-care activities.

Why was support through mobile phone usage (intervention group) more effective? It was suggested that the support through mobile phone usage was affect to certain feeling of lymphedema patients. However, there have been no studies that have clarified patients’ feelings regarding self-care of lymphedema. Therefore, the patients’ feelings and related support were summarized as qualitative results in the present study. The following is a discussion regarding how mobile phone usage enabled effective support.

Effects of mobile phone usage in supporting self-care behaviors

Mobile phones enable communication easily anywhere at anytime. This is their biggest and unique advantage. This study was designed to make the most use of this characteristic of mobile phones.

Mobile phone communication once every two weeks enabled quick response to each patient’s differing symptoms, inquiries, and concerns, which led to psychological stability in the patients, and thus the patients were able to deal appropriately with their given conditions. Kamei et al. reported on the effect of tele-nursing for COPD patients. “Since a tele-nurse objectively assessed each subject’s different signs and symptoms for nursing consultation and mentoring, elderly subjects were able to stay calm so that they could understand how to deal with their challenges and conducted self-care activities that responded to their exacerbation signs”10). In the present study, a similar effect was shown.

The following is a detailed review of the records of communications between patients and nurse. When the patients’ conversation records were analyzed, the category “stabilization of symptoms due to self-care” was extracted as a feeling of the patient continuing self-care. The patients’ recognition of the self-care effect was linked to their belief in the effect of self-care, which finally led to adherence to care. This reveals the progression of a process of patient’ behavior modification through the recognition that self-care activities can prevent exacerbation of lymphedema; that is, it indicates the progression of the process of modification of “attitudes toward behavior” for self-care11).

However, at the same time, categories such as “anxiety towards physical symptoms” and “anxiety towards life activities with lymphedema” were also extracted. In contrast, records concerning such things as “confirmation of self-care” and “sharing the joys of recovery” were extracted from the nurse`s conversations. These are also regarded as supporting activities for the process of modification of “attitudes toward behavior”11). Timely interventions were possible using the mobile phones in categories such as “anxiety towards physical symptoms” and “anxiety towards life activities with lymphedema.” Wavering emotions were caused in patients by trivial questions and uncertainties during daily living, such as “I have one red spot,” “Can I continue to wear stockings even if they are wedged into the back of my knee joints?” and “Can I use an electric heater?” Unless these trivial questions and anxieties are actively addressed, they can get lost in daily living, never arising as issues. However, these anxieties and wavering feelings towards the effects of self-care hinder maintenance of lymphedema self-care activities. Support for resolving these trivial questions and anxieties was made possible using the easily accessible mobile phones.

Ishii et al. showed the importance of “discussions regarding medical treatment” as support for maintaining preventative behaviors in self-care for patients with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the authors stressed the importance of establishing consulting services and telephone consultations to respond to the patient needs of “wanting to have a hassle-free discussion when they are troubled” and “wanting to call if something arises before the next appointment.” Additionally, this would serve as a preventative measure for reduction of activity due to convenience-based decisions, which progresses with time12).

Self-care for lymphedema requires more attentive decision making in a variety of daily living situations than is required for patients with type 2 diabetes. However, there are limits to the knowledge that can be provided beforehand by trying to predict highly individualized daily living situations. Support through mobile phone usage in our study allowed intervention at the time a patient had questions or was anxious and before a convenience-based decision could be made. It also addressed the needs of patients who wanted timely discussions when they were worried. I believe that this led to correct self-care behavior.

The conversation records showed that patients with lymphedema approached self-care with harbored harboring expectations towards recovery and frustration towards unchanging conditions; this was displayed through such comments as “If I apply more pressure, I feel like it will become thinner” and “I work so hard, but nothing is changing too much.” Neglecting such conditions led to the feelings that “effective self-care is difficult and is not possible for me. There is no effect” and to the possibility of the patient abandoning self-care.

In contrast, a method of providing assistance was developed in this study to “confirm self-care” and offer “support and admiration for working hard” in addition to support for “accepting the inability to perform self-care” and “confirming signs of danger and advice for its management.” This assistance worked on “feelings of behavior control” by enabling patients to feel that “actualization of self-care for lymphedema” is easy or on behavioral intent by eliciting patients to start self-care behaviors11).

Senba et al. showed that self-efficacy was the largest factor affecting adherence to exercise therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes and that it is important to encourage self-efficacy13). The “feeling of behavior control” discussed in the present study refers to the feeling that actualization of self-care for lymphedema is simple and can be considered “self-efficacy” for lymphedema self-care. In order to maintain and strengthen this “feeling of behavior control,” it was important to support the patients by positioning the conditions of self-care as a successful experience, especially when the feeling of behavior control wavers, such as by using statements like “Just because some days it is not possible does not mean there won’t be days where you try hard. It’s OK.” Because it was possible to provide timely assistance against wavering feelings of behavior control, we believe the conditions of self-care actualization improved dramatically.

Moreover, the “feeling of behavior control” influenced “behavioral intent” to a large degree14). In particular, supporting patients to continue self-care within the limits of their daily activities may have also enabled patients to continue self-care for longer without abandoning them, and this was achieved through remarks such as “Resting now is more important than self-care” and “Just because some days it is not possible does not mean there won’t be days where you try hard. It’s OK.” Proper maintenance of self-care led to effective self-care. I believe that self-care maintenance was made possible through contributions that strengthened the “feeling of behavior control” and “behavioral intent.”

Effects of mobile phone usage in supporting QOL and mental health status

FACT-G psychological state and behavioral conditions as well as MHP stress conditions improved significantly in the mobile phone-supported (intervention group) patients compared with those supported by normal self-care (control group). This suggested that mobile phone interventions were psychologically effective in patients with lymphedema.

Patients with lymphedema harbor feelings such as “I don’t go out if my legs feel bad,” “My family won’t help with chores even if my legs feel bad,” “shock from being told that I lay down too much,” and “My family and friends don’t understand lymphedema.” This led to a lonely psychological state in the patients, as evidenced by categories such as “feels like my feet are heavy.” Therefore, providing the patients with frequent consultations based on their rapidly changing feelings and accepting the hardships the faced with their edema allowed me to sympathizer with the patients. This relationship likely supported the patients psychologically.

Research has shown that 47% of cancer survivors harbor psychological problems, including reactive depression and anxiety15). Furthermore, it is also known that 27–40% of cancer survivors continue to harbor anxiety and depression16). These psychological conditions are well known to influence self-efficacy17). Therefore, psychological support is absolutely necessary in order to improve the effects of self-care instruction in cancer survivors in an unstable psychological state. The effectiveness of mobile phone support (intervention group) in self-care in this report can be explained through stabilization of the psychological state in cancer survivors such as patients with lymphedema.

According to the planned behavior theory, sentiments including “desire to show good results” and “desire to pull oneself together through harsh words” in the category of “feeling of deserving praise/reprimand” are generated in the relationship between oneself and others. For patients with lymphedema “feeling sadness due to isolation,” the existence of other individuals who understand their condition is important. Moreover, Murakami stated that maintaining relations with people around them such as family and other patients can help during implementation of self-care18). Additionally, Donna highlighted the importance of the reciprocal, trusting relationship between the health- care provider and patient in patient education19). These results suggest that building a trusting relationship through mobile phone support with patients contributes to the promotion of patients’ self-care activities.

Is biweekly interview-based support possible without a mobile phone?

As mentioned previously, there are still very few therapists who treat lymphedema. Even at lymphedema clinics, interview-based support occurs once every three months at the most. Therefore, biweekly support is not practical.

Moreover, biweekly interview-based support is problematic from the patient’s perspective. The stress placed on the patient attempting to visit the clinic frequently while dealing with extra weight due to edema and limited freedom of joints is too great. However, lymphedema patients still seek support.

A mobile phone-based support system means support whenever and wherever it is needed, provided there is a signal. It is possible to address patients’ needs without increasing their burden. Such a support system, whereby patients can receive support while at home, can be extremely worthwhile, particularly for those who are less mobile due to diseases similar to lower leg lymphedema.

Limitations of this research

A statistically significant difference was not obtained in the change in limb circumference, and this could have been the result of insufficient statistical power due to the small sample size and limited time duration. Therefore, further study is required with a statistically appropriate sample size and duration of the study.

In the present study, no scenarios arose in which image assessment was required. Therefore, it could not be confirmed to be effective.

However, when the onset of complications is ruled a possibility, assessment will necessitate detailed information such as the extent of edema, color and dryness of skin, and status of rashes/blistering. The use of mobile telephones makes it possible to obtain such information in “images,” resulting in more accurate assessment and the ability to provide better advice for given circumstances. This would also enable earlier introduction to specialized medical institutions and would be a major means for preventing the complications of lymphedema.

It is essential to prevent complications in order to avoid worsening of lymphedema. Future research should investigate the effectiveness of using mobile telephone images in preventing lymphedema complications and avoiding any worsening.

Conclusion

Compared with routine self-care support, mobile telephone-assisted support is suggested to be effective in improving leg lymphedema patients’ QOL and mental health status as well as their self-care behaviors.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully thank all the patients who participated and Prof. M. Ushikubo of Gunma University School of Health Sciences.

References

- 1.Sanada H, Matsui N, Kitamura K. (translation & supervision). International Consensus. Best Practices for Lymphedema Management. Medical Education Partnership Ltd., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamura K, Akazawa K. Surveying circumstances of other institutions relating to lymphedema after breast cancer surgery and future problems. J Jpn Coll Angiol 2011; 50: 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuhuku M, Michihiro M. Relationship between preventive behaviors against lymphedema and its onset for post-surgery breast cancer patients. Intl Nurs Care Res 2010; 9: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haruta N, Kurayoshi M, Uchida I, et al. Present conditions of our self-care education programs for hospital-based decongestive physiotherapy for lymph edema patients. J Jpn Coll Angiol 2008; 48: 537–541. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd J, Harding J, Green T. Helping patients self-manage their lymphoedema. J Lymphoedema 2010; 5: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masujima M, Sato R. The percetions and coping behaviors regarding lymphedema of patients who developed lymphedema following breast cancer surgery. J Chiba Nurs Res 2008; 14: 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawarasaki M, Asano T, Ohara M, et al. Development and validation of an interactive system of diabetes management and support using mobile telephones. Med Inf 2010; 9: 201–210.

- 8.Yokota K, Doi Y. Effects of nursing intervention during trial overnight stays using mobile telephones for patients with intense anxiety about insulin introduction. Bull Sch Nurs. Osaka Prefect Univ 2011; 17: 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okuda C. Approaches for and Statistical Processing of Assessment Scales. Kinpodo, Japan, 2007; 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamei T, Yamamoto Y, Kazii F. Preventing acute respiratory exacerbation and readmission of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with home oxygen therapy. J Jpn Acad Nurs Sci 2011; 31: 24–33. doi: 10.5630/jans.31.2_24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto C. Foundations of Health Behavior Theory. Ishiyaku Pub, Inc., Tokyo, 2002; 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishii C, Morioka I, Yamada K. Features and factors leading to readmission for type 2 diabetes patients readmitted after rehabilitation admission. J Jpn Soc Nurs Res 2012; 35: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senba Y, Sato K, Koga A, et al. Psychosocial factors impacting adherence to exercise therapy in type 2 diabetes. J Jpn Soc Nurs Res 2009; 29: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheeran P, Trafimow D, Finlay KA, et al. Evidence that the type of person affects the strength of the perceived behavioural control-intention relationship. Br J Soc Psychol 2002; 41: 253–270. doi: 10.1348/014466602760060129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 1983; 249: 751–757. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03330300035030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, et al. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2006; 15: 306–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukemune S, editor. Studying Self-Efficacy: New Developments in Social Learning Theory. Kaneko Shobo, Japan, 1985; 103–141.

- 18.Donna R, Tsuda T. (translation & supervision). Effective Patient Education. Igaku Shoin, Tokyo, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami M, Umeki A, Hanada T. Factors that promote and inhibit self-management in diabetes patients. J Jpn Soc Nurs Res 2009; 32: 28–38. [Google Scholar]