Abstract

Background

Platelet activation is involved in acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Incomplete suppression by low‐dose aspirin treatment of thromboxane (TX) metabolite excretion (urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2) is predictive of vascular events in high‐risk patients. Myeloid‐related protein (MRP)‐8/14 is a heterodimer secreted on activation of platelets, monocytes, and neutrophils, regulating inflammation and predicting cardiovascular events. Among platelet transcripts, MRP‐14 has emerged as a powerful predictor of ACS.

Methods and Results

We enrolled 68 stable ischemic heart disease (IHD) and 63 ACS patients, undergoing coronary angiography, to evaluate whether MRP‐8/14 release in the circulation is related to TX‐dependent platelet activation in ACS and IHD patients and to residual TX biosynthesis in low‐dose aspirin–treated ACS patients. In ACS patients, plasma MRP‐8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 levels were linearly correlated (r=0.651, P<0.001) but significantly higher than those in IHD patients (P=0.012, P=0.044) only among subjects not receiving aspirin. In aspirin‐treated ACS patients, MRP‐8/14 and 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 were lower versus those not receiving aspirin (P<0.001) and still significantly correlated (r=0.528, P<0.001). Higher 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 significantly predicted higher MRP‐8/14 in both all ACS patients and ACS receiving aspirin (P<0.001, adj R2=0.463 and adj R2=0.497) after multivariable adjustment. Conversely, plasma MRP‐8/14 (P<0.001) and higher urinary 8‐iso‐prostaglandin F2α (P=0.050) levels were significant predictors of residual, on‐aspirin, TX biosynthesis in ACS (adjusted R2=0.384).

Conclusions

Circulating MRP‐8/14 is associated with TX‐dependent platelet activation in ACS, even during low‐dose aspirin treatment, suggesting a contribution of residual TX to MRP‐8/14 shedding, which may further amplify platelet activation. Circulating MRP‐8/14 may be a target to test different antiplatelet strategies in ACS.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, aspirin, platelet‐derived factors, platelets, thromboxane

Introduction

Platelets play a fundamental role in the initiation, development, and total extent of myocardial damage in acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Platelet interaction with leukocytes, endothelial cells, macrophages, and circulating progenitor cells plays a crucial role in upholding a proinflammatory and prothrombotic milieu leading to plaque instability and subsequent atherothrombotic events.1 Increased in vivo platelet activation, as reflected by episodic, transient increases in the excretion of thromboxane metabolites (TXM), has been reported in patients with ACS.2 Although enhanced TXA2 biosynthesis is largely suppressed with low‐dose aspirin in this setting, incomplete suppression of TXM excretion has been detected in some patients with unstable angina (UA) and predicts the future risk of serious vascular events and death in high‐risk aspirin‐treated patients.3–4 Given the systemic nature of TXM excretion, involving both platelet and extraplatelet sources, urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 may reflect either platelet cyclooxygenase‐1 (COX‐1)–dependent TX generation or COX‐2–dependent biosynthesis by inflammatory cells and/or platelets, or a combination of the 2, especially in clinical settings characterized by low‐grade inflammation or enhanced platelet turnover.5

Myeloid‐related protein (MRP)‐8 (S100A8) and MRP‐14 (S100A9) are members of the S100 family of calcium‐modulated proteins that regulate myeloid cell function and control vascular inflammation.6 MRP‐14 and MRP‐8 are expressed by neutrophils, monocytes,7–8 and subsets of macrophages during inflammation in different tissues, as well as in atherosclerotic lesions.9 On cell activation, the 2 proteins can form a complex, MRP‐8/14, that translocates to the cytoskeleton and plasma membrane, where it is secreted. MRP‐8/14 broadly regulates vascular inflammation10 and contributes to the biological response to vascular injury, including plaque destabilization and disruption, by promoting leukocyte recruitment and endothelial cell apoptosis.11

A transcriptional platelet profiling approach revealed that the MRP platelet transcript was one of the strongest discriminators of ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), compared with controls with stable ischemic heart disease (IHD).12 Concurrently, in the same cohort, plasma levels of MRP‐8/14 heterodimer were higher in STEMI patients than in stable IHD patients, thus suggesting the platelet origin of circulating MRP‐8/14 in this clinical setting.12 Further studies demonstrated that elevated plasma levels of MRP‐8/14 heterodimer independently predict the risk of first cardiovascular events in healthy individuals and recurrent cardiovascular events and poor prognosis in patients with ACS.13

We hypothesized that activated platelets during an ACS release MRP in the circulation in a TX‐dependent fashion, contributing to further leukocyte recruitment and inflammation, and that low‐dose aspirin treatment is associated with a reduction of MRP release in this setting. Incomplete inhibition of plasma MRP release may be related to residual TX biosynthesis and explain the detrimental phenotype of high on‐aspirin platelet reactivity. This would be consistent with the finding that on‐aspirin treatment but not baseline TXB2 metabolite levels predict adverse outcomes in patients with ACS.14

Our study was aimed to evaluate (1) whether ACS patients exhibit higher MRP‐8/14 levels compared with stable IHD patients and (2) whether MRP‐8/14 release in the circulation is related to TX‐dependent platelet activation in this setting, and to residual TX biosynthesis, in aspirin‐treated patients with an ACS.

Methods

Study Subjects

Patients undergoing coronary angiography at the catheterization laboratory of the Department of Cardiology of Pescara Civil Hospital between February 2008 and September 2013 were enrolled in an institutional review board–approved protocol, and all patients provided written consent. Patient groups included those with (1) IHD (history of angina and/or positive noninvasive test and angiographic coronary heart disease) and (2) a diagnosis of ACS, including STEMI and non–ST‐elevated ACS (NSTE‐ACS).

The first group included 68 consecutive patients referred to our center for elective coronary angiography because of suspected or proved IHD (chronic stable), who were enrolled the day before the procedure after they had signed a written informed consent. Blood and urine samples were obtained before the procedure. Forty‐nine of them were receiving low‐dose aspirin (Cardioaspirina, 100 mg/day) at the time of the evaluation. In the remaining 19 patients, aspirin was administered after blood and urine sampling before the procedure. The reasons for these 19 patients with IHD not receiving aspirin at the time of evaluation included unwillingness of the patient, a recent episode of bleeding requiring aspirin withdrawal, or no definite indication reflecting a suspected diagnosis of IHD, eventually confirmed with subsequent coronary angiography.

The second group included 63 patients with ACS (STEMI, n=16 or NSTE‐ACS, n=47). The diagnosis of STEMI was typical chest pain with serum cardiac enzyme levels twice those of the upper level of normal or cardiac troponin I level ≥0.1 ng/mL, both with persistent electrocardiographic ST‐segment elevation >1 mm in ≥2 contiguous leads or newly occurred left bundle‐branch block. NSTE‐ACS included non‐STEMI (NSTEMI) and UA. NSTE‐ACS was defined as chest pain at rest in the past 48 hours preceding the admission associated with evidence of transient ST‐segment depression and/or prominent T‐wave inversion on 12‐lead electrocardiogram and normal (UA) and/or elevated (NSTEMI) serum troponin T levels. Forty‐seven of ACS patients were already receiving long‐term low‐dose aspirin for ≥1 month at the time of the evaluation for primary or secondary thromboprophylaxis. In the remaining 16 patients, no definite indication for aspirin treatment had emerged before the current event, and aspirin was administered after blood and urine sampling before the procedure.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In all patients, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (as defined in accordance with the criteria of the American Diabetes Association15), dyslipidemia (in accordance with the ATP III criteria16), smoking, family history of early ischemic heart disease, hypertension (systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg or treated hypertension), and previous history of CAD, including previous MI or revascularizations, were carefully obtained. Medications taken on admission were also recorded. The Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score was calculated for all patients17–18; the mean TIMI risk score was 3.4±1.3 for NSTEMI patients and 3.6±1.9 for STEMI patients.

Exclusion criteria included valvular heart disease; severe arrhythmias; clinically significant hepatic, renal, cardiac, or pulmonary insufficiency; malignant diseases (diagnosed and treated within the past 5 years), anemia; acute or chronic inflammatory diseases; pregnancy or lactation; use of drugs known to interfere with platelet function other than aspirin or clopidogrel (nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, ticlopidine, ticagrelor, cilostazol, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) in the previous 10 days; and use of oral anticoagulants or heparin in the previous 2 days.

Design of the Studies

First, a cross‐sectional comparison of circulating MRP‐8/14 and of the urinary excretion of 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 and 8‐iso‐prostaglandin (PG) F2α, in vivo markers of TX‐dependent platelet activation and lipid peroxidation, respectively, was performed among all patients and controls. Second, to test the hypothesis of a platelet origin of plasma MRP‐8/14, patients receiving aspirin (100 mg/day) were compared with the patients not receiving aspirin treatment.

Analytical Measurements

Blood was collected from the arterial sheath before angiography. Blood samples were collected in EDTA‐containing tubes and centrifuged at 3000g for 5 minutes at room temperature within 2 hours after draw. To avoid preactivation due to preanalytical and analytical interferences, one of the major risks when analyzing platelet‐derived molecules, we followed current recommendations regarding the appropriate specimen and preparation of plasma samples to minimize ex vivo release of MRP‐8/14 from platelets.19

Plasma aliquots were stored at −20°C until analysis. Plasma MRP‐8/14 levels were measured by using ELISA (Buhlmann Laboratories). Plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations were determined as previously described.20 Interassay and intra‐assay variations of all measurements were <10%.

Each subject provided a urine sample, immediately before blood sampling. Urine samples were supplemented with the antioxidant 4 hydroxy‐tempo (1 mmol/L; Sigma Chemical Co) and stored at −20°C until extraction. Urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2alpha and 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 were measured with previously described radioimmunoassay methods.21–22 Measurements of these urinary metabolites with radioimmunoassay have been validated through comparison with gas chromatography/mass spectometry, as detailed elsewhere.21–22

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

The main outcome of this study was the difference in plasma MRP‐8/14 levels between ACS patients and stable IHD patients.

Given an expected plasma MRP‐8/14 level of 0.90 μg/mL in chronic IHD patients, the study had 90% power to detect a 2‐fold difference in patients with ACS not treated with aspirin with estimated group SDs of 0.7 for both groups and with a significance level (α) of 5% using a nonparametric adjustment 2‐sided Mann–Whitney test, assuming that the actual distribution is uniform.

Instead, the study had 95% power to detect a reduction by ≥50% in aspirin‐treated ACS patients versus ACS patients not receiving aspirin. This evaluation was performed using the PASS 2005.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine whether each variable had a normal distribution. Variables are summarized as frequency and percentage or median and interquartile range (Q1 to Q3). When necessary, log transformation was used to normalize the data or appropriate nonparametric tests were used (Mann–Whitney U‐test, Spearman's correlation coefficient).

Comparisons of qualitative data between the groups were performed by χ2 test or Fisher exact test, when appropriate. Quantitative variables were analyzed by ANOVA with the Scheffè post‐hoc test to correct for multiple comparisons, with logarithmically transformed data. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess significant predictors of plasma MRP‐8/14 levels and 11‐dehydro‐TXB2, with logarithmically transformed data. Clinically relevant potential confounders, such as age, sex, and medications (aspirin, clopidogrel, and statins), were used as covariates in the models.

Multivariable logistic regression was applied to confirm predictors of high values of MRP‐8/14, dichotomized using median value as threshold. The results of the model were expressed as adjusted odds ratio (ORs).

P‐values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All tests were 2‐tailed, and analyses were performed using a computer software package (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 13.0; SPSS Inc).

Results

ACS Versus Chronic IHD Subjects

The baseline characteristics and cross‐sectional comparisons between the 63 patients with ACS and the 68 with chronic IHD, analyzed as a whole and regardless of ongoing aspirin treatment, are detailed in Table 1. The 2 groups were comparable for most of the clinical characteristics. ACS subjects were more frequently male, with a history of previous MI or revascularization and ongoing treatment with clopidogrel, and had greater mean platelet volume.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of ACS and Chronic IHD Patients

| ACS Patients, n=63 | Chronic IHD Patients, n=68 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 52 (82.5) | 32 (47) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 66.5 (61 to 73.5) | 69 (63 to 77) | 0.062 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 25.8 (24 to 28.1) | 25.8 (24.4 to 28.6) | 0.706 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 21 (33.3) | 14 (22.9) | 0.234 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 43 (68.2) | 54 (81) | 0.102 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 135 (120 to 140) | 140 (125 to 140) | 0.534 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 80 (70 to 80) | 80 (75 to 87.5) | 0.147 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 16 (25.4) | 23 (35.3) | 0.252 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 40 (64.5) | 43 (63.2) | 1.000 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/L | 5.72 (4.78 to 6.67) | 5.28 (4.78 to 5.83) | 0.346 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.57 (3.98 to 5.27) | 4.7 (4.12 to 5.1) | 0.983 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.16 (0.93 to 1.32) | 1.24 (1.06 to 1.42) | 0.090 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.6 (1.28 to 1.99) | 1.63 (1.03 to 1.85) | 0.749 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.84 (2.24 to 3.37) | 3.05 (2.51 to 3.39) | 0.777 |

| Hemoglobin, 109/L | 14.6 (12.9 to 15) | 14.4 (12.9 to 15.6) | 0.923 |

| Red blood cells, 109/L | 4.7 (4.2 to 5.1) | 4.8 (4.4 to 4.9) | 0.802 |

| White blood cells, 109/L | 7.3 (6.0 to 10.5) | 7.7 (6.1 to 8.4) | 0.832 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 210 (163 to 270) | 223.5 (174.7 to 262) | 0.832 |

| Mean platelet volume, fL | 10 (8.9 to 11.2) | 8.4 (8.1 to 9.4) | 0.028 |

| Previous MI or revascularization, n (%) | 33 (52.4) | 23 (33.8) | 0.036 |

| No. of diseased vessels, mean±SD | 1.63±0.94 | 1.44±1.10 | 0.40 |

| Medical treatment, n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 47 (74.6) | 49 (72.1) | 0.844 |

| Clopidogrel | 42 (66.7) | 5 (7.4) | 0.0001 |

| Lipid‐lowering drugs | 43 (69.3) | 39 (57.3) | 0.203 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs | 37 (58.6) | 31 (45.6) | 0.602 |

| β‐Blockers | 27 (43.5) | 32 (47) | 0.727 |

| Digitalis | — | 2 (3) | 0.498 |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 10 (16) | 1 (1.5) | 0.03 |

| Nitrates | 6 (9.52) | 1(1.47) | 0.05 |

| Diuretics | 8 (13.1) | 18 (26.5) | 0.079 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 12 (19.04) | 4 (5.8) | 0.31 |

Values are n (%) or median (Q1 to Q3). The χ2 or Fisher exact test was used for comparison of categorical data, when appropriate. Student t test for unpaired data or Mann–Whitney tests were used for comparison of continuous variables. ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction.

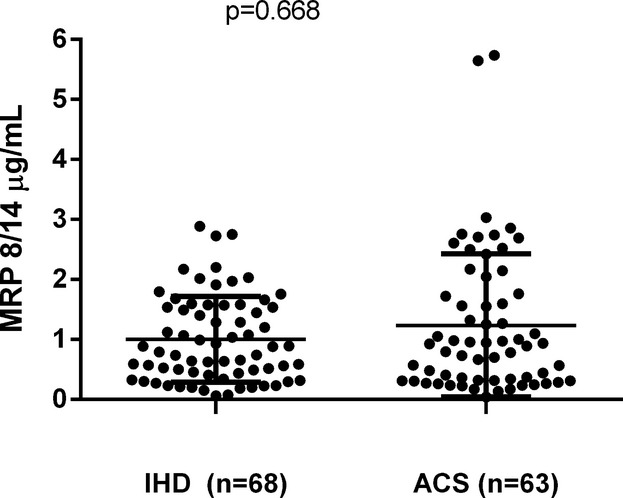

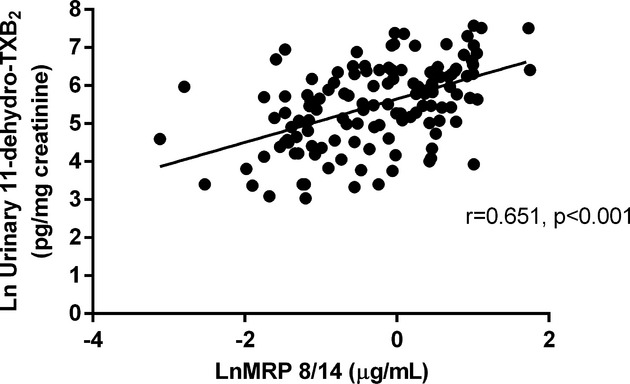

Plasma levels of MRP‐8/14 were not significantly different in ACS patients compared with chronic IHD patients (median [Q1 to Q3] 0.93 [0.32 to 1.76] versus 0.84 [0.41 to 1.56], P=0.668) (Figure 1). As expected, given that approximately three‐quarters of patients in both groups were being treated with low‐dose aspirin, urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 excretion rate was also not significantly different in ACS compared with IHD patients (241 [82 to 608] versus 276 [160 to 507], P=0.737). A significant direct correlation was observed between MRP‐8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 (r=0.651, P<0. 001, Figure 2) only among ACS patients. Both plasma MRP‐8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 did not differ according to the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, history of vascular events, or ongoing medications, including clopidogrel (P=0.374 and 0.335), except for aspirin treatment. These findings prompted us to hypothesize that MRP‐8/14 circulating levels may be related to TX‐dependent platelet activation and, thus, affected by long‐term low‐dose aspirin treatment. Therefore, we stratified patients according to ongoing aspirin treatment.

Figure 1.

Plasma MRP 8/14 in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) patients. Dots represent individual measurements; horizontal bars represent median value for each group. MRP indicates myeloid‐related protein.

Figure 2.

Correlation between plasma MRP 8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 among ACS patients. Linear direct correlation between plasma MRP 8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 in the whole ACS group, regardless of ongoing low‐dose aspirin treatment. Values are logarithmically transformed. ACS indicates acute coronary syndrome; MRP, myeloid‐related protein; TXB2, thromboxane B2.

ACS Versus Chronic IHD Subjects, Stratified According to Ongoing Low‐Dose Aspirin Treatment

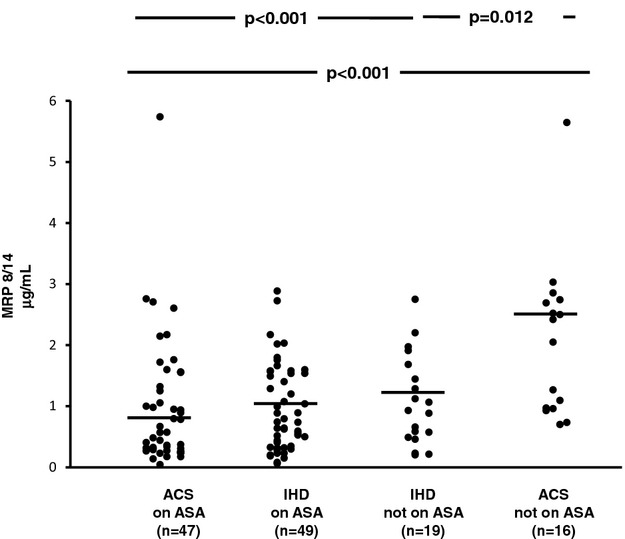

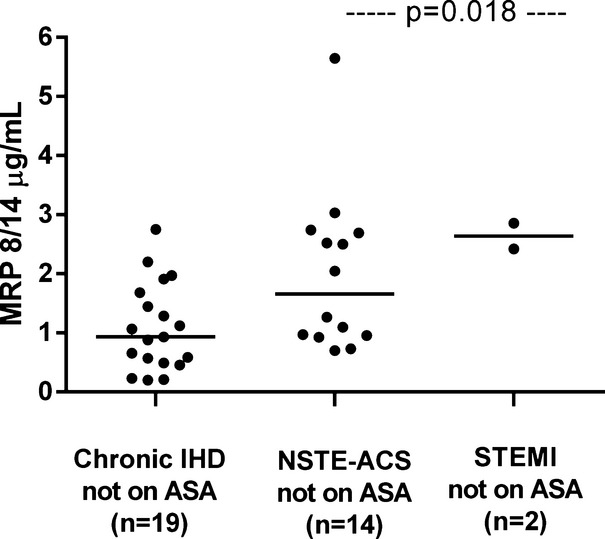

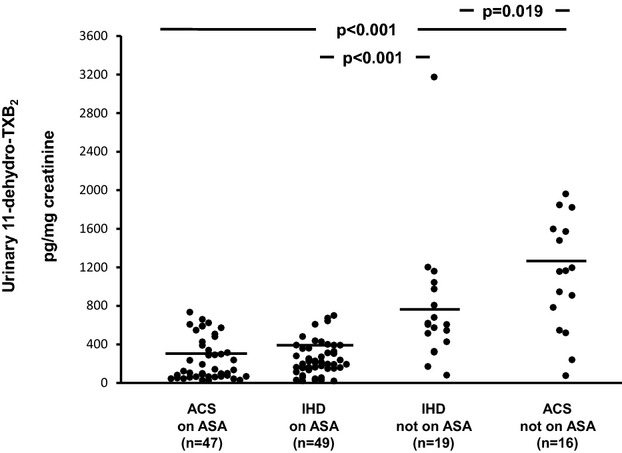

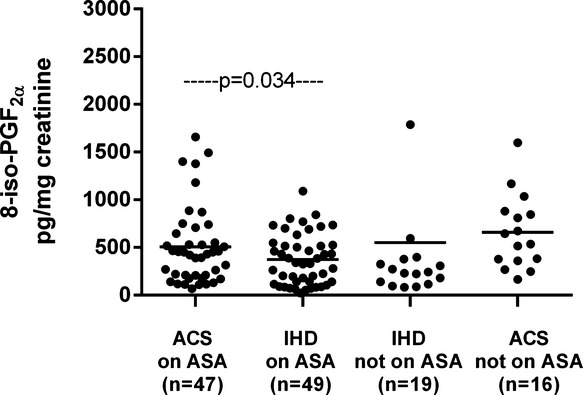

The clinical characteristics of patients with ACS or IHD stratified according to ongoing aspirin treatment are depicted in Table 2. ACS patients not receiving aspirin were fairly balanced with the IHD group not receiving aspirin for most of the clinical characteristics, including cardiovascular risk factors, lipid profile, fasting plasma glucose, and treatment with blood pressure– or lipid‐lowering drugs. As expected, a history of MI or revascularization and ongoing treatment with clopidogrel were more frequent in the ACS group not receiving aspirin than in the chronic IHD counterpart. Similarly, groups receiving aspirin were largely comparable, except that ACS patients receiving aspirin were more frequently male and receiving clopidogrel and calcium channel blocker treatment than were IHD patients receiving aspirin. Among patients not receiving long‐term aspirin treatment, plasma levels of MRP‐8/14 were significantly higher in patients with ACS compared with those of chronic IHD patients (median [Q1 to Q3] 2.23 [0.96 to 2.73] versus 0.93 [0.49 to 1.68], P=0.012) (Figure 3), with STEMI patients exhibiting higher values compared with NSTEMI patients (Figure 4). Urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 and 8‐iso‐PGF2α excretion rates were also significantly higher in ACS patients compared with IHD patients (1161 [606 to 1591] versus 607 [328 to 975], P=0.019, and 591 [365 to 872] versus 244 [129 to 388], P=0.034) (Figures 5 and 6). A direct correlation at the limit of significance (r=0.474, P=0.064) was observed between MRP‐8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 in ACS patients not receiving aspirin but not in the IHD counterpart (data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of ACS and Chronic IHD Patients, Receiving and Not Receiving Aspirin Treatment

| Variable | ACS Patients | P Value* | IHD Patients | P Value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Receiving Aspirin, n=16 | P Value | Receiving Aspirin, n=47 | Receiving Aspirin, n=49 | P Value | Not Receiving Aspirin, n=19 | |||

| Male sex, n (%) | 13 (81.3) | 0.870 | 39 (83) | <0.001 | 21 (42.9) | 0.292 | 11 (57.9) | 0.167 |

| Age, y | 68 (55 to 71) | 0.960 | 66 (61 to 74) | 0.626 | 69 (63 to 77) | 0.989 | 68 (63 to 80) | 0.515 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 26 (25 to 26) | 0.920 | 27 (24 to 30) | 1.000 | 26 (24 to 29) | 0.995 | 26 (24 to 29) | 0.996 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 6 (37.5) | 0.762 | 15 (31.9) | 0.491 | 11 (22.4) | 0.742 | 3 (15.7) | 0.433 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 7 (43.8) | 0.027 | 36 (76.6) | 0.622 | 39 (79.5) | 1.000 | 15 (78.9) | 0.300 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 120 (120 to 140) | 0.661 | 140 (123 to 140) | 1.000 | 130 (125 to 140) | 0.988 | 140 (130 to 143) | 0.647 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 75 (60 to 80) | 0.914 | 80 (70 to 83) | 0.738 | 80 (71 to 85) | 0.974 | 80 (75 to 90) | 0.524 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (18.8) | 0.740 | 13 (27.7) | 0.135 | 21 (42.8) | 0.020 | 2 (10.5) | 0.656 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 9 (56.3) | 0.546 | 31 (65.9) | 0.824 | 35 (71.4) | 0.048 | 8 (42.1) | 0.505 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/L | 4.89 (4.39 to 6.61) | 0.393 | 5.94 (5 to 6.89) | 0.805 | 5.72 (4.83 to 6.61) | 0.429 | 5.22 (4.72 to 5.33) | 0.991 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.26 (3.93 to 5.89) | 1.000 | 4.6 (4.01 to 5.27) | 0.989 | 4.7 (4.19 to 5.25) | 0.992 | 4.63 (3.9 to 5.09) | 0.961 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.27 (0.85 to 1.34) | 1.000 | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.32) | 0.311 | 1.24 (1.09 to 1.47) | 0.795 | 1.21 (0.98 to 1.37) | 0.988 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.86 (0.89 to 2.44) | 0.689 | 1.58 (1.33 to 1.77) | 0.930 | 1.68 (1.23 to 1.87) | 0.531 | 1.31 (0.85 to 1.78) | 0.357 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.97 (2.4 to 4.03) | 0.939 | 2.71 (2.22 to 3.33) | 0.985 | 3.1 (2.66 to 3.41) | 0.826 | 2.97 (1.94 to 3.39) | 0.779 |

| Hemoglobin, 109/L | 16 (15 to 16) | 0.695 | 14 (13 to 15) | 0.981 | 14 (12 to 16) | 0.859 | 14.9 (13.5 to 15.5) | 0.946 |

| Red blood cells, 109/L | 4.89 (4.8 to 4.9) | 0.934 | 4.6 (4.2 to 5.1) | 1.000 | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.9) | 0.918 | 4.91 (4.7 to 5.1) | 1.000 |

| White blood cells, 109/L | 8 (5 to 10) | 0.993 | 7 (6 to 11) | 1.000 | 8 (6 to 9) | 0.936 | 6.8 (5.8 to 8.1) | 0.994 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 188 (165 to 210) | 0.953 | 220 (156 to 273) | 0.976 | 230 (196 to 262) | 0.924 | 197 (141 to 261) | 0.997 |

| Previous MI or revascularization, n (%) | 9 (56.3) | 0.778 | 24 (51.1) | 0.838 | 23 (46.9) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| No. of diseased vessels, mean±SD | 1.67±0.97 | 0.799 | 1.61±0.94 | 0.650 | 1.48±1.08 | 0.677 | 1.29±1.25 | 0.407 |

| TIMI risk score, n (%) | ||||||||

| Low | 9 (56.3) | 0.900 | 10 (21.3) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Intermediate | 6 (37.5) | 0.140 | 22 (46.8) | — | — | — | — | — |

| High | 1 (6.3) | 0.857 | 15 (31.9) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Medical treatment, n (%) | ||||||||

| Clopidogrel | 7 (43.7) | 0.034 | 35 (74.4) | <0.001 | 4 (8.2) | 0.570 | 1 (5.3) | 0.013 |

| Lipid‐lowering drugs | 8 (50) | 0.650 | 35 (74.4) | 0.190 | 31 (63.3) | 0.172 | 8 (42.1) | 0.740 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs | 8 (50.0) | 1.000 | 23 (48.9) | 0.683 | 27 (55.1) | 1.000 | 10 (52.6) | 1.000 |

| β‐Blockers | 4 (25) | 0.142 | 23 (48.9) | 1.000 | 24 (49) | 0.787 | 8 (42.1) | 0.476 |

| Digitalis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 1 (2) | 0.484 | 1 (5.3) | 1.000 |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 2 (12.5) | 1.000 | 8 (17) | 0.014 | 1 (2) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 0.202 |

| Nitrates | 0 (0) | 0.322 | 6 (12.7) | 0.051 | 1 (2) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | — |

| Diuretics | 1 (6.3) | 0.668 | 7 (14.9) | 0.315 | 12 (24.5) | 0.555 | 6 (31.6) | 0.096 |

| PPI | 2 (12.5) | 0.714 | 10 (21.3) | 0.014 | 2 (4.1) | 0.310 | 2 (10.5) | 1.000 |

Values are n (%) or median (Q1 to Q3).The χ2 or Fisher exact test was used for comparison of categorical data, when appropriate. ANOVA with the Scheffè post‐hoc test to correct for multiple comparisons was used for comparison of continuous variables. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction; ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; IHD, ischemic heart disease; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

P value for comparison between ACS and IHD patients receiving aspirin.

P value for comparison between ACS and IHD patients not receiving aspirin.

Figure 3.

Plasma MRP 8/14 in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) patients, receiving aspirin (ASA) and not receiving aspirin. Plasma levels of MRP 8/14 in ACS patients receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin and IHD patients receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin. Dots represent individual measurements; horizontal bars represent median value for each group. MRP indicates myeloid‐related protein.

Figure 4.

Plasma MRP levels in patients not receiving aspirin, according to the assigned diagnosis. Plasma MRP levels in chronic ischemic heart disease (IHD), non‐ST elevated acute coronary syndromes (NSTE‐ACS) and ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients not receiving aspirin treatment. Dots represent individual measurements; horizontal bars represent median value for each group. ACS indicates acute coronary syndrome; MRP, myeloid‐related protein; NSTE, non‐ST elevated.

Figure 5.

Urinary excretion of 11‐dehydro‐thromboxane (TX) B2 in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) patients, receiving aspirin (ASA) and not receiving aspirin. Urinary excretion of 11‐dehydro‐TXB2, in ACS patients receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin and IHD patients receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin. Dots represent individual measurements; horizontal bars represent median value for each group.

Figure 6.

Urinary excretion of 8‐iso‐PGF2α in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) patients, receiving aspirin (ASA) and not receiving aspirin. Urinary excretion of 8‐iso‐PGF2α, in ACS patients receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin and IHD patients receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin. Dots represent individual measurements; horizontal bars represent median value for each group. PG indicates prostaglandin.

Patients Receiving Aspirin Versus Patients Not Receiving Aspirin

No statistically significant differences were found between aspirin‐treated and ‐untreated patients for cardiovascular risk factors, lipid profile, fasting plasma glucose, and treatment with blood pressure– or lipid‐lowering drugs (Table 2). ACS patients receiving aspirin exhibited higher rates of hypertension than untreated subjects, whereas, as expected, IHD patients were more frequently diabetics, with a history of MI or revascularization compared with their counterparts who were not receiving aspirin. Concurrent treatment with clopidogrel was more frequent in aspirin‐treated ACS patients than in non–aspirin‐treated counterparts. However, unlike low‐dose aspirin, clopidogrel did not affect MRP‐8/14 circulating levels in either group (P=0.459 and 0.470 in ACS, receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin, respectively; P=0.106 and 0.105 in chronic IHD, receiving aspirin and not receiving aspirin).

In the whole group of patients, plasma MRP‐8/14 (P=0.002) and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 (P<0.001), but not 8‐iso‐PGF2α (P=0.435), were significantly lower in low‐dose aspirin–treated subjects compared with those not receiving aspirin. A significant direct correlation was observed between MRP‐8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 in all patients receiving aspirin treatment (r=0.423, P<0.001) and in all patients not receiving aspirin treatment (r=0.387, P=0.022), regardless of the diagnosis (ACS or chronic IHD).

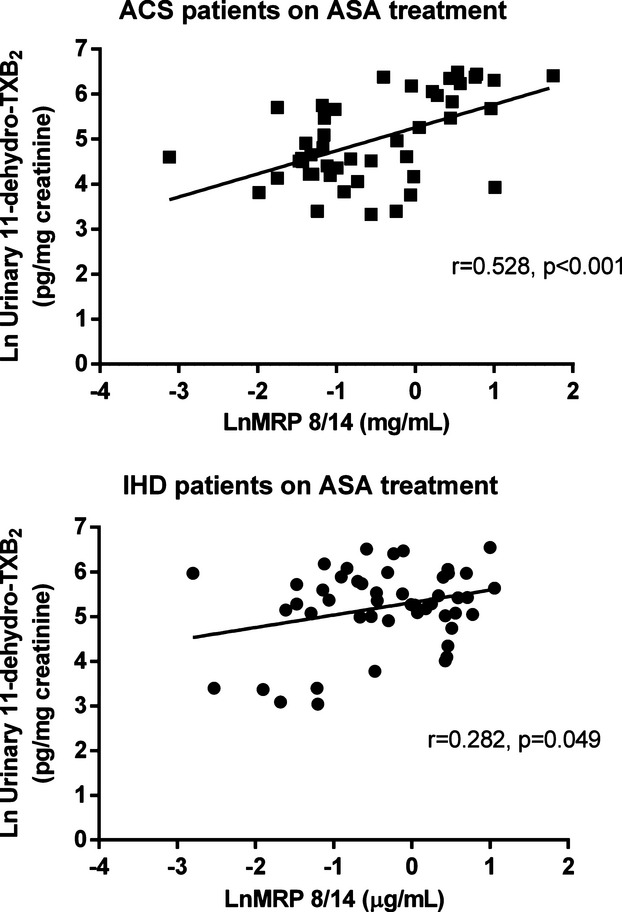

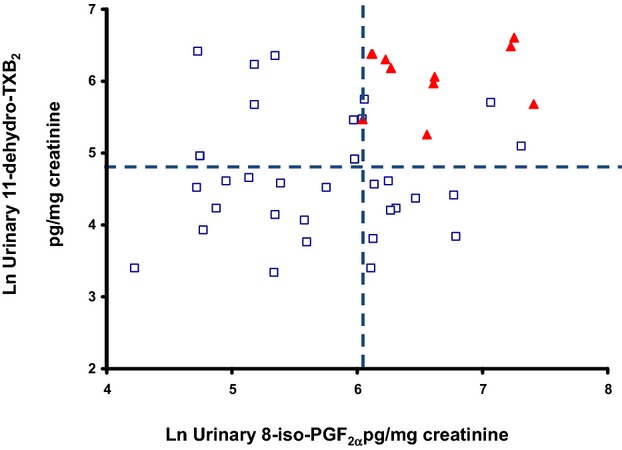

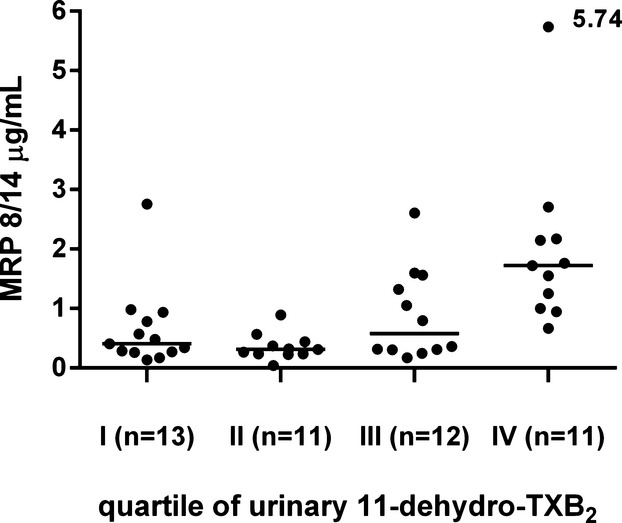

In ACS patients, plasma MRP‐8/14 was significantly lower in low‐dose aspirin–treated subjects compared with those untreated with aspirin at the time of the cross‐sectional evaluation (0.57 [0.28 to 1.32] versus 2.23 [0.96 to 2.73], P<0. 001) (Figure 3). Similarly, urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2, but not 8‐iso‐PGF2α was also significantly lower in ACS patients receiving aspirin at the time of the study, compared with subjects not receiving aspirin (P<0.001) (Figures 5 and 6). A significant direct correlation was also observed between MRP‐8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 among both ACS and stable IHD patients receiving aspirin (r=0.528, P<0.001, and r=0.282, P=0.049, respectively, Figure 7) In low‐dose aspirin–treated subjects, urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 was also related to 8‐iso‐PGF2α both in ACS (r=0.321, P=0.038, Figure 8) and in chronic IHD patients (r=0.497, P<0. 001) (data not shown). In the ACS group, plasma MRP‐8/14 levels increased with increasing quartiles of residual urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 despite ongoing low‐dose aspirin treatment (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Correlations between plasma MRP 8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐thromboxane (TX) B2. Correlation between plasma MRP 8/14 and urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2, in low‐dose aspirin‐treated patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (A) and chronic ischemic heart disease (IHD) (B). Values are logarithmically transformed. MRP indicates myeloid‐related protein; TXB2, thromboxane B2.

Figure 8.

Correlation between urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α and 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 excretion rates in ACS patients on long‐term low‐dose aspirin treatment, according to quartiles of plasma MRP 8/14. Vertical and horizontal lines mark the boundaries of median values of both urinary metabolites. Open and closed symbols represent individual measurements, according to plasma MRP 8/14: open circles first and second quartile; solid triangles, third and fourth quartile. ACS indicates acute coronary syndrome; MRP, myeloid‐related protein; PG, prostaglandin; TX, thromboxane.

Figure 9.

MRP 8/14 plasma levels according to quartiles of residual urinary 11‐dehydro‐thromboxane (TX) B2 in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients receiving aspirin. Plasma levels of MRP 8/14 in ACS patients, divided by quartiles of urinary 11‐dehydro‐ TXB2 during ongoing low‐dose aspirin treatment. MRP indicates myeloid‐related protein.

Determinants of Plasma MRP‐8/14

To further define the relationship between MRP‐8/14, metabolic variables, atherosclerotic risk factors, medications, isoprostane formation, and TX‐dependent platelet activation in either ACS or stable IHD subjects, multiple regression analyses were performed in which plasma MRP‐8/14 was included as the dependent variable. In the ACS group, linear regression yielded a model in which only higher urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 (regression coefficient [β]=0.561, SEM=0.112, P<0. 001) predicted plasma MRP‐8/14, after adjustment for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, medications, and urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α excretion (adjusted R2=0.463). Similarly, in the stable IHD group, only higher urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 (β=0.480, SEM=0.131, P=0.004) predicted plasma MRP‐8/14, after adjustment for other variables (adjusted R2=0.436).

In ACS patients on long‐term low‐dose aspirin treatment, residual TX biosynthesis, despite ongoing aspirin treatment (β=0.497, SEM=0.153, P=0.001), was the only significant predictor of plasma MRP‐8/14 (adjusted R2=0.497). Indeed, among patients with both urinary metabolite excretion in the third and fourth quartiles, ≈75% had MRP‐8/14 above the median (Figure 8).

A multivariate logistic analysis confirmed that only increasing urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 remained significantly associated with higher MRP‐8/14 in both the ACS and IHD groups (OR=4.965, P<0.001 and OR=2.930, P=0.012).

Determinants of TX Biosynthesis

Interestingly, in the ACS group, linear regression with 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 as the dependent variable, yielded a model in which higher plasma MRP‐8/14 (regression coefficient [β]=0.449, SEM=0.133, P<0. 001), lack of ongoing aspirin treatment (β=−0.398, SEM=0.292, P=0.001), and higher urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α (β=0.213, SEM=0.135, P=0.031) predicted urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2, after adjustment for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, and medications other than aspirin (adjusted R2=0.571). Similarly, in the stable IHD group, linear regression yielded a model in which lack of ongoing aspirin treatment (β=−0.461, SEM=0.217, P<0. 001), higher urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α (β=0.239, SEM=0.103, P=0.016) ,and MRP‐8/14 levels (β=0.288, SEM=0.118, P=0.004) predicted urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 after adjustment for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, and medications other than aspirin (adjusted R2=0.471). Plasma MRP‐8/14 (β=0.471, SEM=0.171, P<0. 001) and urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α (β=0. 463, SEM=0.171, P=0.050) were the only significant predictors of residual TX biosynthesis, despite ongoing aspirin treatment, in ACS patients (adjusted R2=0.384, Figure 8).

Discussion

Our data on patients with an ACS or with stable IHD referred to our center for coronary angiography have revealed (1) enhanced TX biosynthesis and MRP‐8/14 plasma levels in ACS patients not receiving aspirin at the time of the vascular event, compared with stable IHD patients; (2) higher F2‐isoprostane formation, as reflected by the urinary excretion of 8‐iso‐PGF2α, not affected by low‐dose aspirin, in ACS versus stable IHD subjects; (3) residual TX biosynthesis despite long‐term aspirin treatment, with post–aspirin‐treatment values of 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 in ACS comparable to those of nonaspirinated healthy subjects, as previously published23; and (4) lower plasma MRP‐8/14 in low‐dose aspirin–treated ACS patients, correlated with TX biosynthesis, suggesting a possible contribution of residual TX to MRP‐8/14 shedding.

The clinical benefit of low‐dose aspirin in the prevention of cardiovascular disease relies on its ability to irreversibly acetylate the platelet COX‐1 and block by 97% to 99% subsequent TX production for the entire life span of the platelets.24

The consistent finding of a 50% reduction with aspirin in the risk of MI or death from vascular causes among UA patients provides a convincing evidence for a role of TXA2 as a platelet‐mediated mechanism implicated in the growth of a coronary thrombus.

Continued TX production despite ongoing low‐dose aspirin treatment, as reflected by the urinary excretion of the TXA2 metabolite 11‐dehydro‐TXB2, has been consistently associated with an increased risk of serious cardiovascular events in patients at high vascular risk,4 a finding subsequently validated externally in an independent data set,25 and may potentially account, at least in part, for the proportion of atherothrombotic events (≈10% to 25%) occurring while receiving aspirin therapy.26

Based on the consistent suppression of TXM excretion by 70% to 80% with low‐dose aspirin in several clinical settings characterized by enhanced platelet activation,24,27 it has been argued that about 20% to 30% of urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 derives either from extraplatelet sources, with the fraction of extraplatelet production likely increasing with the degree of inflammation, or by increased platelet turnover, occurring in particular clinical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus,28 polycythemia vera,5 and ACS.2 In such conditions, a faster renewal of platelet COX‐1 may overcome the effectiveness of the usual once‐daily low‐dose aspirin in inhibiting TX biosynthesis.28 In addition, transient expression of COX‐2 in newly formed platelets or megakaryocytes29 is scarcely sensitive to low‐dose aspirin and may contribute to enhanced TX production in this setting.

Finally, reactive oxygen species induce lipid peroxidation, which generates biologically active F2‐isoprostane, nonenzymatic derivatives of arachidonic acid through its oxidative damage. F2‐isoprostanes, such as 8‐iso‐PGF2alpha, may act as aspirin‐insensitive agonists of the platelet TXA2 receptor, accounting for the less‐than‐complete inhibition of platelet activation.30

We decided to challenge the relationship between MRP‐8/14 and TX biosynthesis in ACS versus chronic IHD patients, because a number of reasons made plasma MRP‐8/14 an ideal candidate to account for the variability in TXM excretion in this setting. First, MRP‐8/14 is a proinflammatory molecule highly expressed in leukocytes, with the potential to reflect the proinflammatory milieu eliciting extraplatelet sources of TX. Second, MRP‐8/14 has been shown to be significantly increased in ACS patients, at both intraplatelet transcript and circulating protein levels12 indicating that platelets and megakaryocytes may function as additional sources of MRP‐8/14. A causal relationship between the presence of large, dense, reactive platelets in the circulation and ACS is supported by the results of many clinical studies. Furthermore, the results of 2 large, prospective, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that mean platelet volume, reflecting accelerated platelet turnover, was the strongest independent predictor of poor outcome in patients with acute MI.31–32 In our cohort, mean platelet volume was significantly higher in ACS subjects compared with chronic IHD patients for the majority of clinical characteristics (Table 1). Notably, evidence indicates that an increase in mean platelet volume in the pathogenesis of ACS can potentially overwhelm current therapeutics.33

Thus, the observation of significantly lower MRP‐8/14 levels is aspirin‐treated subjects, paralleled by the expected finding of lower TXM excretion in this subgroup, prompted us to hypothesize that activated platelets during or in the days preceding an ACS may release MRP‐8/14 in the circulation in a TX‐dependent fashion, whereby ongoing low‐dose aspirin treatment may be associated with a reduction, at least in part, of MRP‐8/14 release in this setting. Enhanced MRP‐8/14 expression, in turn, may contribute to further leukocyte recruitment and inflammation. Indeed, a strong correlation between the circulating inflammatory biomarkers C‐reactive protein and interleukin‐6 and the platelet gene expression of MRP‐14, also known as S100A9, was detected in 1625 participants of the Framingham Heart Study, even after adjustment for cardiovascular disease risk factors.34 Moreover, high MRP‐8, MRP‐14, and MRP‐8/14 levels have been associated with the features of the rupture‐prone lesions,9 and high MRP‐8/14 plasma and plaque levels were independently related to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events after a carotid endarterectomy,35 suggesting a role for high levels of MRP in plaque destabilization and disruption. Here, we showed that incomplete inhibition of plasma MRP‐8/14 release during aspirin treatment may be related to residual TX biosynthesis and may explain the detrimental phenotype of high on‐aspirin platelet reactivity. However, the issue of the potential role of MRP‐8/14 as a predictor for major adverse cardiovascular events in aspirin‐treated subjects with an ACS remains unanswered. Because circulating MRP‐8/14 values in patients receiving aspirin were roughly comparable, whether ACS or chronic IHD, while the 1‐year prognosis in the 2 groups is different to a large extent, it is conceivable that this circulating protein may be considered as a marker for TX‐dependent platelet activation more than as a biomarker of recurrent events in patients already receiving aspirin.

Notably, plasma MRP‐8/14 is correlated to urinary 11‐dehydro‐TXB2 in both non–aspirin‐treated and aspirin‐treated patients. While the first correlation suggests that MRP‐8/14 release may be, in parallel with TX, at least in part COX‐1 derived, the second correlation may reflect both enhanced platelet reactivity, driven by accelerated platelet turnover, which escapes low‐dose aspirin inhibition, and the involvement of nonplatelet cells, likely neutrophils and phagocytic cells, contributing to the plasma levels of this protein complex. Our study design does not allow us to distinguish between failure to suppress platelet COX‐1 and upregulation of COX‐2 expression in newly formed platelets or inflammatory cells. Whether the source of both circulating MRP and residual TX biosynthesis while receiving aspirin reflects either low‐grade inflammation or enhanced platelet turnover, we unraveled a previously unappreciated biochemical link between the release of a proinflammatory, presumably platelet‐derived molecule, and aspirin‐insensitive TX biosynthesis.

In fact, multivariable linear regression analysis yielded a model in which lack of platelet inhibition by aspirin, higher MRP‐8/14 levels, and higher urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α were the only significant predictors of TXM excretion in ACS patients, with MRP‐8/14 accounting for most of the variance in residual TX biosynthesis despite ongoing aspirin treatment. In this regard, it is of interest that an ADP receptor antagonist such as clopidogrel, while inhibiting platelet function, did not, at least cross‐sectionally, affect plasma MRP‐8/14 levels, either in the whole cohort or in the groups stratified according to ongoing aspirin treatment. This observation might further strengthen the hypothesis of a TX‐dependent mechanism underlying the link between platelet activation and MRP‐8/14 release in the circulation.

Our finding that 8‐iso‐PGF2α is enhanced in both STEMI and NSTE‐ACS patients compared with chronic IHD, and contributes to aspirin‐insensitive TX biosynthesis, is largely confirmatory of previous data in a group of UA subjects.36 Here, we also report that, among patients with both urinary 8‐iso‐PGF2α and TXM excretion in the third and fourth quartiles, ≈75% had MRP‐8/14 above the median (Figure 8).

Recent studies indicate that specific changes in the expression/distribution or amount of platelet mRNAs and proteins identify patients with NSTEMI versus stable IHD,37 suggesting that ACS platelets are potentially preconditioned to a higher degree of reactivity on the transcriptional level and that a different composition of the mRNA pool might mediate an increased platelet prothrombotic potential in NSTEMI patients. Among platelet transcripts, MRP‐14 was one of the strongest discriminators of STEMI.12 Because the transcriptional profiling of anucleated platelets, incapable of new transcription, provides a window on gene expression preceding ACS, unbiased by new gene transcription following and triggered by the acute event, we can speculate that the enhanced plasma MRP observed in patients with an ACS undergoing a coronary angiography may reflect events preceding an ACS. Consistently, circulating MRP‐8/14 was recently found to be significantly higher in patients presenting with an MI compared with patients with noncardiac chest pain, evaluated as early as 4 to 6 hours after symptom onset.38 However, whether the detected increase in circulating MRP‐8/14 mirrors the platelet and inflammatory activation preceding the ACS39–40 or that triggered by the coronary event itself remains beyond the scope and discrimination capacity of this study design. In either case, the correlation of MRP‐8/14 with urinary TXM excretion now suggests that its release is associated with TX‐dependent platelet activation.

Our study has some limitations. First, we enrolled patients with ACS with only a cross‐sectional study design and without follow‐up data. Thus, the clinical implications of our pathophysiological findings are elusive and require longitudinal evaluation, including outcome event measures, to be translated into clinical practice. In addition, the subgroups of patients not receiving aspirin were small: although this unbalanced proportion largely mirrors real life, being consistent with the majority of reports in both ACS and chronic IHD subjects undergoing coronary angiography,41–42 it may also yield considerable variability of biomarker levels. Moreover, no direct demonstration of the cellular source of circulating MRP‐8/14 is provided. However, the rate of TXM excretion was, at least in part, largely suppressible by low‐dose aspirin, as observed with the cross‐sectional comparison between aspirinated and not‐on‐aspirin subjects, both with ACS and with stable IHD (Figure 5). Although this comparison was based on a nonrandomized study, the proportional reduction in TXA2 biosynthesis associated with this regimen of aspirin therapy was similar to that reported in other clinical conditions characterized by persistent platelet activation24,43 and was paralleled by a similar reduction in plasma MRP‐8/14 (Figure 3).

We conclude that circulating levels of MRP‐8/14 are associated with TX‐dependent platelet activation in ACS, even during ongoing low‐dose aspirin treatment, suggesting a possible contribution of residual TX to MRP‐8/14 shedding, which, in turn, may further amplify TX biosynthesis and residual platelet activation. Thus, circulating MRP‐8/14 despite long‐term low‐dose aspirin treatment at the time of the acute event may be a target to test different antiplatelet therapies or better administration schemes than currently done with the dogma of once‐daily low‐dose aspirin.44 Once‐daily aspirin does not provide stable 24‐hour antiplatelet protection in a significant proportion of patients with coronary artery disease45 and in both diabetic and nondiabetic subjects at cardiovascular risk,28 largely identified for having accelerated platelet turnover and higher mean body mass index. Interestingly, MRP‐14 platelet transcript was associated with higher body mass index,46 and in our cohort of ACS patients, a trend, at the limit of significance, for higher levels of plasma MRP‐8/14 in obese subjects was observed. A twice‐daily regimen has been shown to overcome incomplete platelet COX‐1 suppression in the 24‐hour interval in both diabetic and nondiabetic subjects at cardiovascular risk28 and may be worth testing in the setting of ACS.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Standards and Samples Analysis.

Sources of Funding

The present research was funded by grants from the Ministry of University and Research and from University of Chieti to Drs Santilli and Davì.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The collaboration of Dr Doriana Vaddinelli in patient enrollment and of Dr Elisabetta Ferrante in the biochemical measurements is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005; 115:3378-3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald DJ, Roy L, Catella F, FitzGerald GA. Platelet activation in unstable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 1986; 315:983-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vejar M, Hackett D, Lipkin DP, Maseri A, Born GV, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C. Dissociation of platelet activation and spontaneous myocardial ischemia in unstable angina. Thromb Haemost. 1990; 63:163-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eikelboom JW, Weitz JI, Johnston M, Yi Q, Yusuf S. Aspirin‐resistant thromboxane biosynthesis and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2002; 105:1650-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santilli F, Romano M, Recchiuti A, Dragani A, Falco A, Lessiani G, Fioritoni F, Lattanzio S, Mattoscio D, De Cristofaro R, Rocca B, Davì G. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and residual in vivo thromboxane biosynthesis in low‐dose aspirin‐treated polycythemia vera patients. Blood. 2008; 112:1085-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:2129-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hessian PA, Edgeworth J, Hogg N. MRP‐8 and MRP‐14, two abundant Ca(2+)‐binding proteins of neutrophils and monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1993; 53:197-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edgeworth J, Gorman M, Bennett R, Freemont P, Hogg N. Identification of p8,14 as a highly abundant heterodimeric calcium binding protein complex of myeloid cells. J Biol Chem. 1991; 226:7706-7713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ionita MG, Vink A, Dijke IE, Laman JD, Peeters W, van der Kraak PH, Moll FL, de Vries JP, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP. High levels of myeloid‐related protein 14 in human atherosclerotic plaques correlate with the characteristics of rupture‐prone lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009; 29:1220-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croce K, Gao H, Wang Y, Mooroka T, Sakuma M, Shi C, Sukhova GK, Packard RR, Hogg N, Libby P, Simon DI. Myeloid‐related protein‐8/14 is critical for the biological response to vascular injury. Circulation. 2009; 120:427-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viemann D, Barczyk K, Vogl T, Fischer U, Sunderkotter C, Schulze‐Osthoff K, Roth J. MRP8/MRP14 impairs endothelial integrity and induces a caspase‐dependent and ‐independent cell death program. Blood. 2007; 109:2453-2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healy AM, Pickard MD, Pradhan AD, Wang Y, Chen Z, Croce K, Sakuma M, Shi C, Zago AC, Garasic J, Damokosh AI, Dowie TL, Poisson L, Lillie J, Libby P, Ridker PM, Simon DI. Platelet expression profiling and clinical validation of myeloid‐related protein‐14 as a novel determinant of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2006; 113:2278-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrow DA, Wang Y, Croce K, Sakuma M, Sabatine MS, Gao H, Pradhan AD, Healy AM, Buros J, McCabe CH, Libby P, Cannon CP, Braunwald E, Simon DI. Myeloid‐related protein 8/14 and the risk of cardiovascular death or myocardial infarction after an acute coronary syndrome in the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy: thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (PROVE IT‐TIMI 22) trial. Am Heart J. 2008; 155:49-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuura E, Guyer K, Yamamoto H, Lopez LR, Inoue K. On aspirin treatment but not baseline thromboxane B2 levels predict adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Thromb Haemost. 2012; 10:1949-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006; 29:S43-S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzo C, Williams K, Hunt KJ, Haffner SM. The National Cholesterol Education Program—Adult Treatment Panel III, International Diabetes Federation, and World Health Organization definitions of the metabolic syndrome as predictors of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30:8-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, Diercks D, Egan J, Ghaemmaghami C, Menon V, O'Neil BJ, Travers AH, Yannopoulos D. Part 10: acute coronary syndromes: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010; 122:S787-S817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, Cairns R, Murphy SA, de Lemos JA, Giugliano RP, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. TIMI risk score for ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: an intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation. 2000; 102:2013-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferroni P, Riondino S, Vazzana N, Santoro N, Guadagni F, Davì G. Biomarkers of platelet activation in acute coronary syndromes. Thromb Haemost. 2012; 108:1109-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davì G, Averna M, Catalano I, Barbagallo C, Ganci A, Notarbartolo A, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C. Increased thromboxane biosynthesis in type IIa hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1992; 85:1792-1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Ciabattoni G, Creminon C, Lawson J, Fitzgerald GA, Patrono C, Maclouf J. Immunological characterization of urinary 8‐epi‐prostaglandin F2 alpha excretion in man. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995; 275:94-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciabattoni G, Maclouf J, Catella F, FitzGerald GA, Patrono C. Radioimmunoassay of 11‐dehydrothromboxane B2 in human plasma and urine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987; 918:293-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santilli F, Rocca B, De Cristofaro R, Lattanzio S, Pietrangelo L, Habib A, Pettinella C, Recchiuti A, Ferrante E, Ciabattoni G, Davì G, Patrono C. Platelet cyclooxygenase inhibition by low‐dose aspirin is not reflected consistently by platelet function assays: implications for aspirin “resistance”. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:667-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davì G, Patrono C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2482-2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Weitz JI, Johnston M, Yi Q, Yusuf S. Incomplete inhibition of thromboxane biosynthesis by acetylsalicylic acid: determinants and effect on cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2008; 118:1705-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrono C, Coller B, FitzGerald GA, Hirsh J, Roth G. Platelet‐active drugs: the relationships among dose, effectiveness, and side effects: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004; 126:234S-264S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santilli F, Davì G, Consoli A, Cipollone F, Mezzetti A, Falco A, Taraborelli T, Devangelio E, Ciabattoni G, Basili S, Patrono C. Thromboxane‐dependent CD40 ligand release in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocca B, Santilli F, Pitocco D, Mucci L, Petrucci G, Vitacolonna E, Lattanzio S, Mattoscio D, Zaccardi F, Liani R, Vazzana N, Del Ponte A, Ferrante E, Martini F, Cardillo C, Morosetti R, Mirabella M, Ghirlanda G, Davì G, Patrono C. The recovery of platelet cyclooxygenase activity explains interindividual variability in responsiveness to low‐dose aspirin in patients with and without diabetes. J Thromb Haemost. 2012; 10:1220-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocca B, Secchiero P, Ciabattoni G, Ranelletti FO, Catani L, Guidotti L, Melloni E, Maggiano N, Zauli G, Patrono C. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression is induced during human megakaryopoiesis and characterizes newly formed platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002; 99:7634-7639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santilli F, Mucci L, Davì G. TP receptor activation and inhibition in atherothrombosis: the paradigm of diabetes mellitus. Intern Emerg Med. 2011; 6:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu SGBR, Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Eikelboom JW, Konkle B, Mohler ER, Reilly MP, Berger JS. Mean platelet volume as a predictor of cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010; 8:148-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taglieri N, Saia F, Rapezzi C, Marrozzini C, Bacchi Reggiani MI, Palmerini T, Ortolani P, Melandri G, Rosmini S, Cinti L, Alessi L, Vagnarelli F, Villani C, Branzi A, Marzocchi A. Prognostic significance of mean platelet volume on admission in an unselected cohort of patients with non ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2011; 106:132-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin JF, Kristensen SD, Mathur A, Grove EL, Choudry FA. The causal role of megakaryocyte‐platelet hyperactivity in acute coronary syndromes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012; 9:658-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McManus DD, Beaulieu LM, Mick E, Tanriverdi K, Larson MG, Keaney JF, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Freedman JE. Relationship among circulating inflammatory proteins, platelet gene expression, and cardiovascular risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013; 33:2666-2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ionita MG, Catanzariti LM, Bots ML, de Vries JP, Moll FL, Kwan Sze S, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP. High myeloid‐related protein: 8/14 levels are related to an increased risk of cardiovascular events after carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 2010; 41:2010-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cipollone F, Ciabattoni G, Patrignani P, Pasquale M, Di Gregorio D, Bucciarelli T, Davì G, Cuccurullo F, Patrono C. Oxidant stress and aspirin‐insensitive thromboxane biosynthesis in severe unstable angina. Circulation. 2000; 102:1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camera M, Brambilla M, Facchinetti L, Canzano P, Spirito R, Rossetti L, Saccu C, Di Minno MN, Tremoli E. Tissue factor and atherosclerosis: not only vessel wall‐derived TF, but also platelet‐associated TF. Thromb Res. 2012; 129:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vora AN, Bonaca MP, Ruff CT, Jarolim P, Murphy S, Croce K, Sabatine MS, Simon DI, Morrow DA. Diagnostic evaluation of the MRP‐8/14 for the emergency assessment of chest pain. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012; 34:229-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rittersma SZ, van der Wal AC, Koch KT, Piek JJ, Henriques JP, Mulder KJ, Ploegmakers JP, Meesterman M, de Winter RJ. Plaque instability frequently occurs days or weeks before occlusive coronary thrombosis: a pathological thrombectomy study in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2005; 111:1160-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ojio STH, Tanaka T, Ueno K, Yokoya K, Matsubara T, Suzuki T, Watanabe S, Morita N, Kawasaki M, Nagano T, Nishio I, Sakai K, Nishigaki K, Takemura G, Noda T, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara H. Considerable time from the onset of plaque rupture and/or thrombi until the onset of acute myocardial infarction in humans: coronary angiographic findings within 1 week before the onset of infarction. Circulation. 2000; 102:2063-2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang LHX, Zhang W, Wu LD, Liu YS, Hu B, Bi CL, Chen YF, Liu XX, Ge C, Zhang Y, Zhang M. Dickkopf‐1 as a novel predictor is associated with risk stratification by GRACE risk scores for predictive value in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a retrospective research. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e54731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Douglas PSPM, Bailey SR, Dai D, Kaltenbach L, Brindis RG, Messenger J, Peterson ED. Hospital variability in the rate of finding obstructive coronary artery disease at elective, diagnostic coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:801-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santilli F, Davì G, Basili S, Lattanzio S, Cavoni A, Guizzardi G, De Feudis L, Traisci G, Pettinella C, Paloscia L, Minuz P, Meneguzzi A, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C. Thromboxane and prostacyclin biosynthesis in heart failure of ischemic origin: effects of disease severity and aspirin treatment. J Thromb Haemost. 2010; 8:914-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renda G, De Caterina R. Measurements of thromboxane production and their clinical significance in coronary heart disease. Thromb Haemost. 2012; 108:6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henry P, Vermillet A, Boval B, Guyetand C, Petroni T, Dillinger JG, Sideris G, Sollier CB, Drouet L. 24‐hour time‐dependent aspirin efficacy in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Thromb Haemost. 2011; 105:336-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freedman JE, Larson MG, Tanriverdi K, O'Donnell CJ, Morin K, Hakanson AS, Vasan RS, Johnson AD, Iafrati MD, Benjamin EJ. Relation of platelet and leukocyte inflammatory transcripts to body mass index in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2010; 122:119-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Standards and Samples Analysis.