Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Communication about end-of-life care is a core clinical skill. Simulation-based training improves skill acquisition, but effects on patient-reported outcomes are unknown.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the effects of a communication skills intervention for internal medicine and nurse practitioner trainees on patient- and family-reported outcomes.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Randomized trial conducted with 391 internal medicine and 81 nurse practitioner trainees between 2007 and 2013 at the University of Washington and Medical University of South Carolina.

INTERVENTION

Participants were randomized to an 8-session, simulation-based, communication skills intervention (N = 232) or usual education (N = 240).

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Primary outcome was patient-reported quality of communication (QOC; mean rating of 17 items rated from 0–10, with 0 = poor and 10 = perfect). Secondary outcomes were patient-reported quality of end-of-life care (QEOLC; mean rating of 26 items rated from 0–10) and depressive symptoms (assessed using the 8-item Personal Health Questionnaire [PHQ-8]; range, 0–24, higher scores worse) and family-reported QOC and QEOLC. Analyses were clustered by trainee.

RESULTS

There were 1866 patient ratings (44% response) and 936 family ratings (68% response). The intervention was not associated with significant changes in QOC or QEOLC. Mean values for postintervention patient QOC and QEOLC were 6.5 (95% CI, 6.2 to 6.8) and 8.3 (95% CI, 8.1 to 8.5) respectively, compared with 6.3 (95% CI, 6.2 to 6.5) and 8.3 (95% CI, 8.1 to 8.4) for control conditions. After adjustment, comparing intervention with control, there was no significant difference in the QOC score for patients (difference, 0.4 points [95% CI, −0.1 to 0.9]; P = .15) or families (difference, 0.1 [95% CI, −0.8 to 1.0]; P = .81). There was no significant difference in QEOLC score for patients (difference, 0.3 points [95% CI, −0.3 to 0.8]; P = .34) or families (difference, 0.1 [95% CI, −0.7 to 0.8]; P = .88). The intervention was associated with significantly increased depression scores among patients of postintervention trainees (mean score, 10.0 [95% CI, 9.1 to 10.8], compared with 8.8 [95% CI, 8.4 to 9.2]) for control conditions; adjusted model showed an intervention effect of 2.2 (95% CI, 0.6 to 3.8; P = .006).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Among internal medicine and nurse practitioner trainees, simulation-based communication training compared with usual education did not improve quality of communication about end-of-life care or quality of end-of-life care but was associated with a small increase in patients’ depressive symptoms. These findings raise questions about skills transfer from simulation training to actual patient care and the adequacy of communication skills assessment.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00687349

Observational studies have suggested that communication about end-of-life care is associated with decreased intensity of care, increased quality of life, and improved quality of dying.1,2 In addition, interventions that focus on communication about palliative and end-of-life care, using palliative care specialists, have demonstrated improved quality of life, decreased symptoms of depression, and reduced intensity of care at the end of life.3–5 Whether similar benefits can be obtained by training clinicians other than palliative care specialists in communication about palliative and end-of-life care remains unclear.

Simulation to learn skills for communicating bad news to patients with cancer forms the basis of a 4-day workshop for medical oncology fellows.6 This workshop has been associated with significant improvement in participants’ ability to deliver bad news and discuss transitions to palliative care. Clinicians can learn skills for communicating about palliative care in small-group facilitated settings using simulated patients and family members.6–10 A systematic review of communication skills interventions noted the effectiveness of interventions using simulation but observed that no studies have shown an effect on patient-reported outcomes.11

We conducted a randomized trial to examine whether a communication skills–building workshop aimed at internal medicine and nurse practitioner trainees, using simulation during which trainees practiced skills associated with palliative and end-of-life care communication, had any effect on patient-, family-, and clinician-reported outcomes. Our hypothesis was that this workshop would increase the discussion of palliative and end-of-life care by trainees and improve patient, family, and clinician ratings of the quality of communication about end-of-life care as well as the quality of end-of-life care.

Methods

Trial Design

Internal medicine residents, subspecialty fellows, and nurse practitioner trainees were randomized to the simulation-based intervention vs usual education. Randomization was at the level of the trainee, but the primary outcome was assessed at the level of patients clustered under trainees. Randomization was stratified by site, year of training, and profession and occurred in blocks of 4. Outcomes were assessed by surveying 3 types of evaluators: patients, families, and clinicians. Evaluators’ encounters with trainees occurred before or after the time of the intervention. Trainees could not be blinded to group assignment, but outcome evaluators and staff collecting evaluations were.

Human subjects approval was obtained from the University of Washington and Medical University of South Carolina institutional review boards. Trainees provided written consent. Evaluators were provided an information sheet; we obtained a waiver for written documentation of consent. Race/ethnicity, an important predictor of attitudes toward end-of-life care, was based on self-reports using fixed categories.

Participants

Trainee Participants

Trainees were recruited from University of Washington and Medical University of South Carolina between 2007 and 2012. Eligible trainees included all internal medicine residents and fellows in pulmonary and critical care, oncology, geriatrics, nephrology, and palliative medicine subspecialties. Nurse practitioners were eligible if they were currently enrolled in, or had recently completed, training programs that included care for adults with life-threatening or chronic illnesses.

Patient-Evaluators

Patients were identified by screening medical records, identifying those who had encounters with an enrolled trainee. Encounters occurred between trainees and patients in primary care clinics or on prespecified inpatient services (eg, general medicine, medical intensive care unit, hematology-oncology). Eligible patients had a high likelihood of having a discussion about end-of-life care, and eligibility criteria included median survival of approximately 1 to 2 years: life-limiting illness (eg, metastatic or stage IV cancer, oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stage III or IV heart failure, Child-Pugh class C liver disease) or comorbidities suggesting severe illness (score ≥5 on the Charlson Comorbidity Index12). We also included patients with documentation of communication about end-of-life care (palliative care consult or do not resuscitate order), an intensive care unit stay of 72 hours or longer, or age 80 years or older with a hospital stay of 72 hours or longer. For outpatients, we required 3 or more visits with the trainee to enhance opportunity to discuss end-of-life care.

We also required that all evaluators remember the trainee well enough to evaluate his or her communication skills, and all surveys included a trainee’s photograph. We used in-person and mail-based recruitment procedures, with 3 contacts for nonrespondents. Patients could be contacted to evaluate up to 2 trainees and provided ratings between October 2007 and January 2013.

Family-Evaluators

Family members were identified 1 of 3 ways: participating patients identified family involved with their care; family of non-communicative, otherwise-eligible, patients; and family of eligible patients who died. Families could be contacted to evaluate up to 2 trainees and provided ratings between November 2007 and January 2013.

Clinician-Evaluators

Clinician-evaluators included nurses and attending physicians who observed care provided by the trainee. Nurse-evaluators were identified through screening patient medical records and review of unit schedules. Physician-evaluators were faculty members identified through patient medical records or clinical schedules. Clinician-evaluators were not limited in the number of trainees they could evaluate and provided ratings between April 2008 and January 2013.

Timing of Evaluation Survey Distribution

Surveys were distributed to evaluators based on documented encounters between trainee and evaluator. Encounters for the preintervention phase occurred in the 6-month period preceding the workshop/control phase; encounters for the postintervention phase occurred in the 10 months following the workshop/control phase. The surveys did not reference a specific encounter but asked evaluators to assess trainees across all encounters. We did not require that the encounters include discussion of end-of-life care, because we hypothesized that the intervention would activate trainees to initiate such discussions.

Intervention

The intervention was adapted from a residential workshop associated with improved communication skills for oncology fellows.6,13 Our intervention comprised eight 4-hour sessions led by 2 faculty: a physician and a nurse. A content outline and facilitator guide were developed. Each session included (1) a brief didactic overview, including a demonstration role-play by faculty; (2) skills practice using simulation (simulated patients, family, or clinicians); and (3) reflective discussions. Each session addressed a specific topic (eg, building rapport; giving bad news; talking about advance directives; nurse-physician conflict; conducting a family conference; do-not-resuscitate status and hospice; and talking about dying).6,14 The intervention used 2 patient stories that unfolded sequentially, starting with diagnosis of serious illness and ending with death. In a before-after analysis of these intervention trainees, the course was associated with significant improvements in communication skills regarding giving bad news and responding to emotion, as assessed by standardized patient encounters.15

Outcomes

Primary Outcome—Quality of Communication

The quality of communication (QOC) questionnaire was developed from qualitative interviews and focus groups with patients, families, and clinicians and is available online.16–18 It is a multi-item survey (18 items for patients and clinicians; 19 for family): 1 item measures the overall quality of communication, and the remaining items measure specific aspects of communication. Each item is rated from 0 (“poor”) to 10 (“absolutely perfect”). The instrument has acceptable internal consistency, and construct validity was supported through correlations with conceptually related measures (eg, number of discussions with the clinician about end-of-life care and extent to which the clinician knows the patient’s treatment preferences).17

For this study, we used a previously validated composite score constructed as the respondent’s mean score for valid responses to all ratings, after first recoding responses of “clinician didn’t do this” to 0.17 If the respondent omitted rating an item, this item contributed to neither numerator nor denominator. For example, a patient who indicated that the trainee had not performed 6 of 17 items, had a rating of 0 on 4 items, a rating of 6 on 5 items, and a rating of 10 on 2 items would receive a composite score of 2.94 ({[0 · 10]+[6 · 5]+[10 · 2]}/17). Although a minimal clinically significant difference (MCID) is not known for the quality of communication questionnaire, a 7-item subscale was responsive in a prior randomized trial of a communication intervention, showing a significant but small improvement (0.6 points, effect size = 0.21).19 In addition to the composite measure, we examined a single-item rating of overall communication.

Secondary Outcomes—Quality of End-of-Life Care

The quality of end-of-life care (QEOLC) questionnaire is a multi-item (26 items for patients and families; 10 for clinicians) survey developed through qualitative studies for assessing the quality of clinician skill at providing end-of-life care.20–23 The instrument has acceptable internal consistency.24 Construct validity was supported through correlation with conceptually related measures: physician knowledge of palliative care; patient and family satisfaction with care; and nurse ratings of physician’s care.24 We used a composite measure constructed as the respondent’s mean for valid responses from all items, similar to the QOC questionnaire described above.

Depression

Symptoms of depression were measured using the 8-item Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), a widely used measure of depressive symptoms, appropriate for populations with chronic medical conditions.25,26 The PHQ-8 has excellent reliability, test-retest stability, and sensitivity and specificity,27 as well as demonstrated validity28 and responsiveness to interventions.29 PHQ-8 scores sum component symptoms (on a 4-point scale) and can range from 0 (no symptoms during the preceding 2 weeks) to 24 (8 symptoms experienced nearly every day), with high scores reflecting greater depression. A score was computed for all respondents who answered at least 7 items, with scores for patients answering only 7 items weighted to compensate for the missing item. The score was defined as missing if fewer than 7 items were answered. The MCID for the PHQ-8 is a 5-point change.30,31

Functional Status

Functional status was measured with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12), which has been used with patients with chronic illness32 and older populations33 and provides a standard composite measure with good psychometric characteristics including internal reliability, test-retest stability, validity,34,35 and responsiveness.36 Valid responses to all 12 items are required for computation of the composite score. Scores on the physical component of the SF-12 can range from 10.5 to 70.1; for the mental component, the potential range is 7.8 to 72.0. For both components, higher scores represent better health. The MCID has been estimated between 4 and 7 points.37

Statistical Analyses

The association of the intervention with all outcomes of interest was tested using regression models. Because trainee randomization was stratified, site and randomization strata (trainee type and level of training) were included as covariates in all models.

Data provided by patient-, family-, and clinician-evaluators were cross-classified, with some evaluators providing ratings for multiple trainees, and trainees receiving ratings from multiple evaluators. Because there was minimal clustering of trainees under patient- or family-evaluators, 1 survey was selected per evaluator, with selections favoring surveys maximizing the number of trainees evaluated. This allowed analysis using simple clustered models, with patient- and family-evaluators clustered under trainees. Each model included only trainees for whom there was at least 1 valid response on the outcome for both the preintervention and post-intervention periods. Models regressed each outcome on study period (preintervention or postintervention), randomization group, and the primary predictor of interest: an interaction term for study period and randomization group. For patients and families, scores on the QOC and QEOLC questionnaires demonstrated ceiling effects; therefore, these scores were modeled as censored variables using Tobit regression. All other outcomes were modeled with robust linear regression. All patient and family models were based on restricted maximum likelihood estimation. In addition to the primary analyses, we performed 2 post hoc analyses on patient QOC scores, restricting the samples to patients whose care was provided in the out-patient setting or patients who rated their own health status as “poor” on a single health-status question.

We retained the cross-clustered design of clinician data, given the greater clustering of trainees under evaluators. For these analyses, a clinician-evaluator could evaluate trainees in one or both randomization groups. Each level-1 model regressed the outcome on study period; the level-2 model regressed the level-1 intercept on randomization group and the covariates for randomization strata and regressed the level-1 slope on randomization group only. Of primary interest was the coefficient for the level-1 slope regressed on randomization group. We modeled all clinician outcomes with robust linear regression, using full maximum likelihood. Models were based on surveys with complete data on all predictors and the outcome of interest.

We conducted an additional analysis using propensity scoring to weight patient scores on the primary outcome to examine for potential nonresponse bias. This model was weighted to make surveys used in the analysis representative of all surveys requested from patients (eAppendix in Supplement). These analyses showed no evidence that nonresponse or exclusion of surveys from the analysis produced bias in the primary study finding (eAppendix and eTable 1 in Supplement).

Sample size was determined by the number of trainees in the 2 institutions. Power to find a 2-point change and large effect size (γ = 0.80) on the QOC questionnaire was estimated as 0.80, assuming 200 trainees per group; intraclass correlation coefficient estimates of 0.11 for patients and 0.35 for families; 4 or 5 evaluators per trainee; and 2-sided α = .05. The 2-point change on the QOC questionnaire was based on the hypothesis that the intervention would improve at least 2 QOC items by 1 point.

All inferential statistics were based 2-sided tests, with P < .05 as statistically significant. We used IBM SPSS version 19 (IBM SPSS); Mplus version 7 (http://www.statmodel.com); and HLM version 7.0 (Scientific Software International Inc) for all analyses.

Results

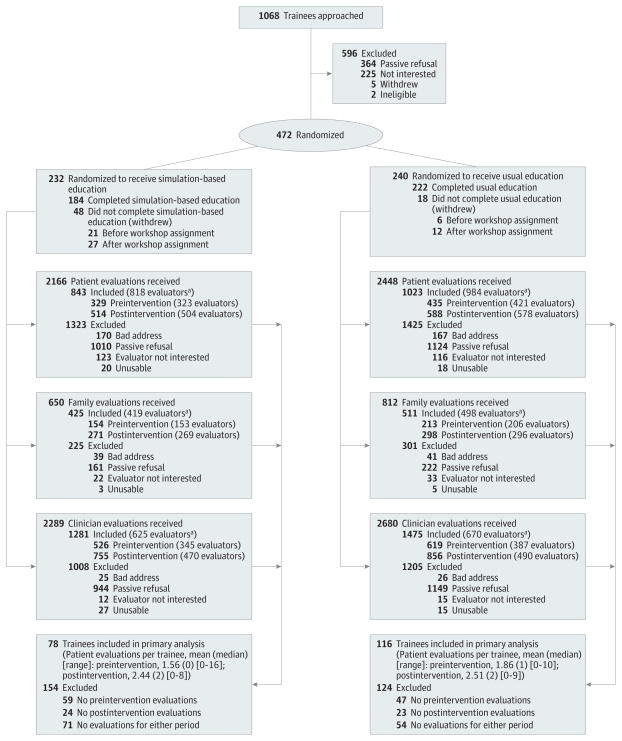

We approached 1068 eligible trainees, of whom 472 (44%) were randomized (Figure 1). Participation rates were higher for physicians than for nurse practitioners (55% vs 18%; P < .001). Among physicians, participation rates were higher for first-year residents than for those in later postgraduate years (81% vs 39%; P < .001) and for women than for men (60% vs 52%; P = .04). Participation rates were also higher for non-Hispanic whites compared with racial/ethnic minorities (61 vs 52%; P = .03). Of the 406 trainees who completed the study, 184 (45%) were randomized to the intervention. Characteristics of the randomized trainees are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Enrollment of Study Participants.

aEvaluators could be duplicated.

Table 1.

Trainee Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention (n = 211)

|

Control (n = 234)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Available, No. | Statistic | Data Available, No. | Statistic | |

| Recruitment site, No. (%) | 211 | 234 | ||

|

| ||||

| University of Washington | 141 (67) | 158 (68) | ||

|

| ||||

| Medical University of South Carolina | 70 (33) | 76 (32) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 193 | 30.5 (5.8) | 215 | 30.3 (4.8) |

|

| ||||

| Women, No. (%) | 211 | 121 (57) | 234 | 136 (58) |

|

| ||||

| Racial/ethnic minority, No. (%) | 207 | 48 (23) | 229 | 64 (28) |

|

| ||||

| Trainee type, No. (%) | 211 | 234 | ||

|

| ||||

| Resident | 161 (76) | 174 (74) | ||

|

| ||||

| Fellow | 17 (8) | 24 (10) | ||

|

| ||||

| NP student | 27 (13) | 32 (14) | ||

|

| ||||

| Community NP or RN | 6 (3) | 4 (2) | ||

|

| ||||

| Postgraduate training year, median (IQR) | 205 | 1.0 (1–2) | 230 | 1.0 (1–2) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline experience with end-of-life issues, No. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| No. of patients to whom trainee had given bad news | 191 | 155 | ||

|

| ||||

| 0 | 48 (25) | 44 (28) | ||

|

| ||||

| 1–3 | 63 (33) | 49 (32) | ||

|

| ||||

| 4–9 | 42 (22) | 35 (23) | ||

|

| ||||

| ≥10 | 38 (20) | 27 (17) | ||

|

| ||||

| No. of times trainee had discussed end-of-life care with patients | 190 | 154 | ||

|

| ||||

| 0 | 28 (15) | 33 (21) | ||

|

| ||||

| 1–3 | 78 (41) | 62 (40) | ||

|

| ||||

| ≥4 | 84 (44) | 59 (38) | ||

|

| ||||

| No. of times observed senior clinician discuss end-of-life care | 190 | 155 | ||

|

| ||||

| 0 | 7 (4) | 6 (4) | ||

|

| ||||

| 1–3 | 61 (32) | 42 (27) | ||

|

| ||||

| ≥4 | 122 (64) | 107 (69) | ||

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NP, nurse practitioner; RN, registered nurse.

We received 1866 patient evaluations completed by 1717 patients evaluating 345 trainees: 1569 patients evaluated 1 trainee and 148 patients evaluated 2 trainees. We received 936 surveys completed by 898 family respondents, evaluating 295 trainees: 861 evaluating 1 trainee and 37 evaluating 2 trainees. We also received 2756 surveys completed by 890 clinicians evaluating 325 trainees: 360 evaluating 1 trainee, 176 evaluating 2 trainees, 345 evaluating 3 to 15 trainees, and 9 evaluating 16 to 27 trainees. Table 2 shows characteristics of patient-, family-, and clinician-evaluators.

Table 2.

Evaluator Characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Patients

|

Family Members

|

Clinicians

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention

|

Control

|

Intervention

|

Control

|

|||||||

| Data Available, No. |

Statistic | Data Available, No. |

Statistic | Data Available, No. |

Statistic | Data Available, No. |

Statistic | Data Available, No. |

Statistic | |

| Site, No. (%) | 771 | 946 | 412 | 486 | 890 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| University of Washington | 449 (58) | 508 (54) | 184 (45) | 194 (40) | 525 (59) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Medical University of South Carolina | 322 (42) | 438 (46) | 228 (55) | 292 (60) | 365 (41) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 771 | 64.9 (14.4) | 946 | 65.6 (14.1) | 387 | 56.8 (13.7) | 463 | 56.6 (13.5) | 866 | 40.6 (11.3) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Women, No. (%) | 771 | 316 (41) | 946 | 412 (44) | 406 | 299 (74) | 477 | 353 (74) | 890 | 567 (64) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Racial/ethnic minority, No. (%) | 770 | 256 (33) | 946 | 301 (32) | 390 | 124 (32) | 468 | 144 (31) | 843 | 177 (21) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Married/partnered, No. (%)b | 740 | 370 (50) | 912 | 451 (49) | 393 | 191 (49) | 465 | 227 (49) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Education level, No. (%) | 743 | 909 | 388 | 464 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| ≤8th grade | 43 (6) | 72 (8) | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Some high school | 70 (9) | 110 (12) | 23 (6) | 32 (7) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| High school diploma/GED | 149 (20) | 214 (24) | 76 (20) | 90 (19) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Some college | 253 (34) | 268 (29) | 135 (35) | 183 (39) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 4-y college degree | 123 (17) | 127 (14) | 82 (21) | 86 (19) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Postcollege study | 105 (14) | 118 (13) | 64 (16) | 66 (14) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Income level, No. (%), $c | 652 | 803 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| <500 | 41 (6) | 53 (7) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 501–1000 | 141 (22) | 164 (20) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1001–1500 | 77 (12) | 113 (14) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1501–2000 | 69 (11) | 76 (9) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2001–3000 | 84 (13) | 92 (11) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 3001–4000 | 69 (11) | 97 (12) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| ≥4001 | 171 (26) | 208 (26) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Outpatient, No. (%) | 771 | 195 (25) | 946 | 237 (25) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | 771 | 946 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Cancer | 188 (24) | 222 (23) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| COPD | 60 (8) | 73 (8) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Other lung disease | 10 (1) | 8 (1) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| CHF | 91 (12) | 91 (10) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| End-stage liver disease | 59 (8) | 67 (7) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Patient died, No. (%)d | 412 | 67 (16) | 486 | 76 (16) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Clinician type, No. (%) | 890 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| MD, OD, NP, PA | 447 (50) | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| RN, LPN, health technician | 443 (50) | |||||||||

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GED, General Educational Development; LPN, licensed practical nurse; MD, medical doctor; NP, nurse practitioner; OD, doctor of osteopathy; PA, physician assistant; RN, registered nurse.

Table based on the 1717 unduplicated patients, 898 unduplicated family members, and 890 unduplicated clinician-evaluators who returned 1 or more usable surveys. The clinicians could not be divided into intervention and control groups, because a clinician-evaluator could evaluate trainees from both randomization groups.

For patients, this variable indicates marital status; for family members, it indicates whether the family respondent was the patient’s spouse or partner.

Monthly pretax household income from all sources.

Patient’s death occurred before family respondent completed survey.

Evaluator response rates were calculated based on the surveys sent rather than individual participants and excluded from the denominator respondents who indicated that they did not recognize the trainee. The rates were 44% of patient surveys, 68% of family surveys, and 57% of clinician surveys. If it is further assumed that the same proportions of nonrespondents and respondents did not recognize the trainee, the estimated response rates are 56% of patient surveys, 74% of family surveys, and 64% of clinician surveys.

Among patients, response rates differed according to the eligibility criteria, with significantly lower rates for patients in hospice care (27% vs 42%; P < .001), those who had documented communication about end-of-life care (34% vs 42%; P = .002), inpatients older than 80 years (31% vs 42%; P < .001), and those with cancer (36% vs 42%; P = .002) or end-stage liver disease (32% vs 41%; P = .01). Response rates were also lower for minority groups (self-reported) compared with white/non-Hispanic (38% vs 44%; P < .001) and for patients recruited from the inpatient setting compared with the outpatient setting (37% vs 66%; P < .001). The remaining eligibility criteria, patient sex, and study period were not associated with response rates (eTable 2 in Supplement).

Family members were significantly less likely to complete surveys as a result of the patient’s death (29% vs 78%; P < .001) or if the patient was a member of a racial/ethnic minority group (60% vs 69%; P = .003). Family member response rates were not associated with any other patient characteristics or study period (eTable 3 in Supplement).

Among clinician-evaluators, physicians were significantly more likely to return surveys than nurses (65% vs 52%; P < .001). There was no evidence of differential response rates by sex of clinician-evaluator or trainee, trainee type, or setting (eTable 4 in Supplement).

Primary Outcome—QOC Scores

The mean QOC score was 6.5 (95% CI, 6.2 to 6.8) on postintervention patients’ surveys for intervention trainees, compared with 6.3 (95% CI, 6.2 to 6.5) on surveys for all other patient groups (ie, patients of control trainees from both periods and preintervention patients of intervention trainees). After covariate adjustment, there was no significant association between the intervention and QOC score (Table 3 and eTable 5 in Supplement) For the single-item rating of overall QOC, mean scores were 8.4 (95% CI, 8.1 to 8.7) on postintervention ratings of intervention trainees and 8.5 (95% CI, 8.3 to 8.6) for all other ratings. After covariate adjustment, there were no significant differences associated with the intervention. Scores on the QOC questionnaire (both the total score and single-item rating) were significantly higher at the Medical University of South Carolina than at the University of Washington and significantly lower for first-year residents than for other trainees (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Intervention and Ratings of Quality of Trainees’ Communication and End-of-Life Carea

| Outcome/ Predictors |

Patients

|

Family

|

Clinicians

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trainees Evaluated/ Evaluations, No. |

b (95% CI)b |

P Value |

Trainees Evaluated/ Evaluations, No. |

b (95% CI)b |

P Value |

Trainees Evaluated/ Clinician- Evaluators/ Evaluations, No. |

b (95% CI)b |

P Value |

|

| QOC scorec | 194/1224 | 116/543 | 213/803/2199 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Intervention | 0.38 (−0.14 to 0.90) | .15 | 0.11 (−0.77 to 0.98) | .81 | 0.19 (−0.08 to 0.47) | .17 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | −0.27 (−0.65 to 0.12) | .18 | 0.76 (0.18 to 1.35) | .01 | 0.01 (−0.23 to 0.24) | .94 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Study period | 0.03 (−0.29 to 0.34) | .86 | 0.07 (−0.48 to 0.62) | .81 | 0.06 (−0.13 to 0.24) | .56 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Study sited | 0.34 (0.07 to 0.62) | .02 | 0.25 (−0.17 to 0.68) | .25 | 0.08 (−0.16 to 0.33) | .51 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Stratum | .001 | .52 | .003 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| R1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| R2 | 0.52 (0.131 to 0.920) | .009 | −0.29 (−0.79 to 0.22) | .26 | 0.25 (−0.03 to 0.54) | .08 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| R3/fellow | 0.50 (0.14 to 0.86) | .007 | −0.02 (−0.52 to 0.48) | .93 | 0.47 (0.20 to 0.74) | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| NP | 0.78 (0.46 to 1.10) | <.001 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Overall QOCe | 189/1119 | 114/518 | 211/794/2139 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Intervention | 0.22 (−0.74 to 1.18) | .65 | 0.06 (−1.26 to 1.37) | .94 | 0.14 (−0.16 to 0.42) | .36 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | −0.54 (−1.28 to 0.20) | .15 | 0.46 (−0.54 to 1.46) | .37 | 0.04 (−0.30 to 0.22) | .74 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Study period | 0.02 (−0.58 to 0.62) | .95 | −0.24 (−1.03 to 0.54) | .54 | 0.08 (−0.12 to 0.28) | .45 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Study sited | 0.80 (0.28 to 1.32) | .002 | 0.92 (0.21 to 1.64) | .01 | 0.02 (−0.24 to 0.28) | .87 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Stratum | <.001 | .27 | .009 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| R1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| R2 | 1.19 (0.38 to 2.00) | .004 | −0.65 (−1.76 to 0.46) | .25 | 0.29 (−0.03 to 0.62) | .08 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| R3/fellow | 0.79 (0.13 to 1.45) | .02 | 0.30 (−0.61 to 1.20) | .52 | 0.45 (0.15 to 0.75) | .004 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| NP | 1.92 (0.68 to 3.17) | .002 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| QEOLCf | 196/1250 | 117/546 | 213/788/2135 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Intervention | 0.25 (−0.27 to 0.77) | .34 | 0.06 (−0.70 to 0.82) | .88 | 0.18 (−0.10 to 0.46) | .20 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | −0.39 (−0.79 to 0.02) | .06 | 0.26 (−0.33 to 0.84) | .38 | −0.01 (−0.25 to 0.23) | .95 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Study period | 0.10 (−0.23 to 0.43) | .55 | −0.08 (−0.59 to 0.42) | .74 | 0.04 (−0.15 to 0.23) | .68 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Study sited | 0.38 (0.11 to 0.64) | .006 | 0.44 (−0.02 to 0.90) | .06 | −0.01 (−0.26 to 0.23) | .92 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Stratum | 0 | .36 | <.001 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| R1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| R2 | 0.62 (0.22 to 1.02) | .003 | −0.30 (−0.80 to 0.21) | .25 | 0.32 (0.03 to 0.62) | .03 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| R3/fellow | 0.46 (0.12 to 0.80) | .008 | 0.19 (−0.43 to 0.81) | .55 | 0.55 (0.27 to 0.82) | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| NP | 0.52 (0.28 to 0.76) | <.001 | |||||||

Abbreviations: NP, nurse practitioner; QEOLC, Quality of End-of-life Care questionnaire; QOC, Quality of Communication questionnaire; R1, first-year resident; R2, second-year resident; R3, third-year resident.

Results with mean scores shown in eTables 5 through 7 in Supplement.

For linear regression models, the b coefficient represents expected number of points change in the observed outcome variable with a 1-point increase in the predictor. For Tobit regression models, it represents the expected number of points change in an uncensored latent variable represented by the observed outcome with a 1-point increase in the predictor.

Estimates were based on robust linear regression. Intercepts (estimated preintervention mean for year-1 residents at University of Washington in the control condition) for the evaluator groups were, respectively, 6.001, 6.445, and 7.343.

0 = University of Washington; 1 = Medical University of South Carolina.

This outcome was censored from above and modeled with Tobit regression. It was modeled as a linear outcome in the cross-classified clinician sample. Intercepts (estimated preintervention mean for first-year residents at University of Washington in the control condition) for the 3 evaluator groups were, respectively, 9.295, 9.221, and 7.502.

For patients and family members, this outcome had a strong ceiling effect and was modeled as censored from above, using Tobit regression. Intercepts (estimated mean value during the preintervention period for first-year residents at University of Washington in the control condition) for the 3 evaluator groups were, respectively, 8.197, 8.244, and 7.472.

To explore potential subgroups for whom end-of-life discussions might be more feasible or relevant, we performed 2 post hoc analyses, restricting the sample to outpatients and to patients who rated their health status as “poor” on a single-item health-status question. The intervention was not associated with improvement in QOC score among outpatients (b = 0.041 [95% CI, −1.36 to 1.44]) but was associated with significant improvement in QOC score among patients who rated their health status as “poor” (b = 1.430 [95% CI, 0.28 to 2.58]).

The family- and clinician-rated QOC scores were not associated with the intervention (Table 3). For family surveys, single-item ratings were significantly higher at the Medical University of South Carolina than at the University of Washington, but there was no association with training year; neither site nor training year was associated with differences in QOC scores (eTable 6 in Supplement). For clinician surveys, first-year residents had significantly lower scores on both the QOC score and single-item rating, but site was not associated with either (eTable 7 in Supplement). Propensity modeling showed no evidence that nonresponse or exclusion of surveys from the analysis produced bias in the primary study finding (eTable 1).

Secondary Outcome—QEOLC Scores

Findings for the QEOLC score showed similar results (Table 3). For patient ratings, the mean score for trainees after the intervention was 8.3 (95% CI, 8.1 to 8.5), compared with 8.3 (95% CI, 8.1 to 8.4) for all other surveys. After covariate adjustment there was no association with the intervention, but there was a significant association with study site (higher at Medical University of South Carolina) and training year (lowest for first-year residents). Family ratings showed no association with the intervention and also showed no association with study site or training year. Clinician ratings showed no association with the intervention and no association with study site; however, first-year residents had significantly lower scores.

Depressive Symptoms

Patients’ depressive symptoms were significantly associated with the intervention (Table 4). The mean score on the PHQ-8 for patients of trainees who had received the intervention was 10.0 (95% CI, 9.1 to 10.8), compared with 8.8 (95% CI, 8.4 to 9.2) for patients of control trainees and preintervention trainees in the intervention group. After covariate adjustment, the intervention was associated with a significant increase in depressive symptoms, with a preintervention-to-postintervention increase in the intervention group of 2.2 PHQ-8 points (95% CI, 0.6 to 3.8) compared with the control group (less than the MCID of 5 points.) There was no association with study site, but depression scores for patients of the most senior trainees were significantly lower than those for patients of first-year residents. The intervention was not associated with depression scores in family respondents.

Table 4.

Associations of the Intervention With Depression and Functional Status of Evaluatorsa

| Outcome/Predictors | Patients

|

Family

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trainees Evaluated/Evaluations, No. | b (95% CI)b | P Valuec | Trainees Evaluated/Evaluations, No. | b (95% CI)b | P Valuec | |

| Depression scored | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Interventione | 193/1121 | 2.20 (0.62 to 3.78) | .006 | 108/463 | 1.07 (−1.09 to 3.23) | .33 |

|

| ||||||

| Groupf | −0.77 (−1.93 to 0.40) | .20 | 0.20 (−1.56 to 1.96) | .82 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Study periodg | −0.85 (−1.84 to 0.14) | .09 | −0.28 (−1.49 to 0.92) | .64 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Study siteh | 0.11 (−0.64 to 0.86) | .78 | −0.58 (−1.89 to 0.74) | .39 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Stratumi | .003 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| R1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| R2 | −0.42 (−1.58 to 0.74) | .48 | 0.55 (−0.86 to 1.96) | .45 | ||

|

| ||||||

| R3/fellow | −1.63 (−2.54 to −0.72) | <.001 | −0.48 (−2.32 to 1.36) | .61 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Physical statusj | 178/938 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Interventione | 1.26 (−1.22 to 3.75) | .32 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Groupf | 0.10 (−1.56 to 1.75) | .91 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Study periodg | −0.46 (−2.04 to 1.13) | .57 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Study siteh | 0.53 (−0.71 to 1.77) | .41 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Stratumi | <.001 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| R1 | 0.000 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| R2 | 1.83 (0.34 to 3.33) | .02 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| R3/fellow | 2.87 (1.11 to 4.64) | .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Mental statusk | 178/938 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Interventione | 0.34 (−2.52 to 3.20) | .82 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Groupf | −0.76 (−2.83 to 1.31) | .47 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Study periodg | 0.59 (−1.08 to 2.25) | .49 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Study siteh | −0.24 (−1.59 to 1.12) | .73 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Stratumi | .003 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| R1 | 0.000 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| R2 | 0.78 (−1.11 to 2.68) | .42 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| R3/fellow | 3.01 (1.17 to 4.86) | .001 | ||||

Abbreviations: R1, first-year resident; R2, second-year resident; R3, third-year resident.

All outcomes were modeled within evaluator types (patient or family) using robust linear regression models, evaluators clustered under trainees, and estimates based on restricted maximum likelihood. The model for each outcome and evaluator group included only the predictors shown on the rows, included only 1 evaluation per evaluator, and included only those trainees who had at least 1 valid outcome score for both the preintervention and postintervention periods. Results with mean scores are shown in eTables 5–7 in Supplement.

b = expected change in the outcome score with a 1-point increase in the row predictor.

All P values and 95% CIs were based on 2-tailed tests. P values for overall differences between strata were based on likelihood ratio tests; other P values were based on Wald test.

Standard composite measure for the PHQ-8 Depression Questionnaire.

Interaction term computed as randomization group × time point (0 = control group or preintervention evaluation for intervention group; 1 = postintervention evaluation for intervention group).

Main effect of randomization group (0 = control, 1 = intervention).

Main effect of time: effect of the pre/post indicator (ie, whether the evaluator’s last encounter with the trainee occurred before [0] or after [1] the workshop series to which the trainee was assigned).

0 = University of Washington; 1 = Medical University of South Carolina.

Stratified randomization was done within the 2 study sites, using 5 randomization strata: (R1; R2; R3/fellow; students in nurse practitioner or nursing education programs; and community nurses, nurse practitioners or registered nurses). Neither of the nursing strata had cases in these analyses and are omitted from the Table. The R1 stratum was the reference group in all analyses.

Norm-based standardized physical component score from the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire. Intercept (estimated mean for cases scoring 0 on all predictors) = 28.777. Assessed in patients only.

Norm-based standardized mental component score from the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire. Intercept (estimated mean for cases scoring 0 on all predictors) = 42.930. Assessed in patients only.

Functional Status

Patients’ SF-12 physical and mental component scores were not associated with the intervention. The mean physical status score for patients of postintervention trainees was 30.8 (95% CI, 29.4 to 32.1), compared with 29.7 (95% CI, 29.0 to 30.4) for patients of control trainees and patients of preintervention trainees. Means for the mental component scores for the 2 groups were 43.7 (95% CI, 42.1 to 45.2) and 43.7 (95% CI, 42.9 to 44.4). Adjusted models showed no significant intervention effect (Table 4).

Discussion

Communication skills can be taught using simulation, but to our knowledge no previous studies have examined patient-reported outcomes of such training.6–11 We conducted a randomized trial of a simulation-based communication skills-building workshop for internal medicine residents, subspecialty fellows, and nurse practitioners that assessed the effects of this intervention on patient-, family-, and clinician-reported outcomes. In another publication, we showed that this intervention was associated with acquisition of new skills in delivering bad news and responding to emotion, as assessed by standardized-patient encounters.15 In this study, we found there was no significant change in ratings of QOC or QEOLC as assessed by patients, family, or clinicians. We found significant improvement in ratings of QOC for patients who assessed their health status as “poor,” for whom communication about palliative care may be particularly relevant; however, as a post hoc subgroup analysis, this must be interpreted with caution.

A possible explanation for the absence of change in patient and family ratings of QOC and QEOLC may be linked to the difficulties that untrained or unprompted patients or family have in accurately rating clinician communication or end-of-life care. Although an intervention to identify and provide feedback related to patient-specific barriers to communication about end-of-life care was associated with a significant increase in patient-rated quality of end-of-life communication, the effect size was small.19 These measures of communication and care are relatively new, and their responsiveness, sensitivity, and MCID are not known.17,24 Ratings by trained standardized patients are more reliable for assessing communication skills than ratings by untrained patients.38,39 Similarly, a randomized trial of a communication skills workshop for oncologists showed improvement in communication skills as assessed by trained raters but no improvement in patient ratings.7,40 Therefore, our findings may not negate the value of using simulation for communication skills training (which appears to have improved trainees’ communication skills15) but suggest that patients and family members may require training or prompting to provide accurate assessment of these skills. It is also possible that the time lag between evaluators’ working with the trainee and completing the evaluation affected evaluators’ ability to rate accurately or that patient contact with multiple clinicians diluted the effect of a trained clinician. It is also possible that the intervention was not effective despite improved scores with standardized patients15 or that improvement in communication skills in a standardized-patient encounter does not translate to actual patient care.

The increase in patients’ depressive symptoms associated with the intervention is noteworthy. Although statistically significant, the 2.2-point change in PHQ-8 scores is less than the MCID and is the result of one among multiple comparisons. However, patients could experience depressive symptoms or feelings of sadness as a result of discussion about end-of-life care. An observational study showed that patients’ understanding of an incurable prognosis was associated with lower patient ratings of their physicians’ communication,41 supporting the possibility that increasing patients’ awareness of prognosis may trigger negative experiences. Our finding that the increase in patients’ depressive symptoms was significantly greater for first-year residents suggests this increase might be associated with the skill level of the clinician having the discussion. Future studies should explore the effect of discussing end-of-life care on patients’ psychological symptoms and satisfaction with care. If these findings are substantiated, studies should also consider ways to mitigate negative effects while achieving the positive effects of these discussions.3–5

The randomized design of our study and the number of participants are important strengths, but additional limitations should be considered. First, the participation rates were fairly high for physicians but lower for nurse practitioners, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the generalizability of these findings to training at other institutions is not certain. Second, participation rates for evaluators could allow nonresponse bias. Sicker patients were less likely to participate, limiting our ability to assess the intervention among patients most likely to have an end-of-life discussion. Third, because evaluations were completed up to 10 months after the intervention, there could be shorter-term benefits that were not identified.

Conclusion

Among internal medicine and nurse practitioner trainees, simulation-based communication skills training compared with usual education did not improve quality of communication about end-of-life care or quality of end-of-life care but was associated with a small increase in patients’ depressive symptoms. These findings raise questions about skills transfer from simulation training to actual patient care and the adequacy of communication skills assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (R01NR009987).

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: Drs Curtis and Engelberg had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Curtis, Back, Shannon, Doorenbos, Kross, Engelberg.

Acquisition of data: Curtis, Back, Ford, Shannon, Doorenbos, Kross, Edlund, Arnold, O’Connor, Engelberg.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Curtis, Back, Ford, Downey, Shannon, Doorenbos, Reinke, Feemster, Arnold, Engelberg.

Drafting of the manuscript: Curtis, Back, Downey, Kross, Engelberg.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Curtis, Back, Ford, Downey, Shannon, Doorenbos, Reinke, Feemster, Edlund, Arnold, O’Connor, Engelberg.

Statistical analysis: Downey.

Obtained funding: Curtis, Shannon, Engelberg.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Curtis, Back, Ford, Downey, Shannon, Doorenbos, Kross, Reinke, Edlund, O’Connor, Engelberg.

Study supervision: Back, Ford, Shannon, Engelberg.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Drs Feemster and Engelberg reported receiving salary support from a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr Reinke reported receiving grants or grants pending from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Palliative Care Research Center and receiving payment for development of educational presentations from the European Respiratory Society. No other authors reported disclosures.

References

- 1.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9307):650–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szmuilowicz E, Neely KJ, Sharma RK, Cohen ER, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB. Improving residents’ code status discussion skills: a randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):768–774. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton JM, Adler JL, O’Callaghan A, et al. Intensive communication skills teaching for specialist training in palliative medicine: development and evaluation of an experiential workshop. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):585–591. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander SC, Keitz SA, Sloane R, Tulsky JA. A controlled trial of a short course to improve residents’ communication with patients at the end of life. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):1008–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242580.83851.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of training methods. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(6):356–366. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fryer-Edwards K, Arnold RM, Baile W, Tulsky JA, Petracca F, Back A. Reflective teaching practices: an approach to teaching communication skills in a small-group setting. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):638–644. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232414.43142.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson VA, Back AL. Teaching communication skills using role-play: an experience-based guide for educators. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(6):775–780. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bays A, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of small group, simulated patient interventions [published online November 1, 2013] J Palliat Med. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Au DH, Patrick DL. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(2):200–205. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1086–1098. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):868–874. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;141(3):726–735. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care: perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Patients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest. 2002;122(1):356–362. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Ambrozy DM, et al. Dying patients’ need for emotional support and personalized care from physicians: perspectives of patients with terminal illness, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:236–246. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00694-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carline JD, Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Physicians’ interactions with health care teams and systems in the care of dying patients: perspectives of dying patients, family members, and health care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelberg RA, Downey L, Wenrich MD, et al. Measuring the quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(6):951–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löwe B, Gräfe K, Kroenke K, et al. Predictors of psychiatric comorbidity in medical outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(5):764–770. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000079379.39918.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Gräfe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBurney CR, Eagle KA, Kline-Rogers EM, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients 7 months after a myocardial infarction: factors affecting the Short Form-12. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(12):1616–1622. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.17.1616.34121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeder BA, Chad KE, Harrison EL, et al. Saskatoon in motion: class- versus home-based exercise intervention for older adults with chronic health conditions. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5(1):74–87. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life in older people: a structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(7):1651–1668. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frosch DL, Rincon D, Ochoa S, Mangione CM. Activating seniors to improve chronic disease care: results from a pilot intervention study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1496–1503. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hopman WM, Harrison MB, Coo H, Friedberg E, Buchanan M, VanDenKerkhof EG. Associations between chronic disease, age and physical and mental health status. Chronic Dis Can. 2009;29(3):108–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiscella K, Franks P, Srinivasan M, Kravitz RL, Epstein R. Ratings of physician communication by real and standardized patients. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):151–158. doi: 10.1370/afm.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(17):1877–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shilling V, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Factors affecting patient and clinician satisfaction with the clinical consultation: can communication skills training for clinicians improve satisfaction? Psychooncology. 2003;12(6):599–611. doi: 10.1002/pon.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(17):1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.