Abstract

Black men suffer disproportionately from hypertension. Antihypertensive medication nonadherence is a major contributor to poor blood pressure control, yet few studies consider how psychosocial functioning may impact black men’s medication adherence. The authors examined the direct and mediating pathways between depressive symptoms, psychosocial stressors, and substance use on antihypertensive medication nonadherence in 196 black men enrolled in a clinical trial to improve hypertension care and control. The authors found that greater depressive symptoms were associated with more medication nonadherence (β=0.05; standard error [SE], 0.01; P<.001). None of the psychosocial stressor variables were associated with antihypertensive medication nonadherence. Alcohol misuse was associated with increased medication nonadherence (β=0.81; SE, 0.26; P<.01), but it did not mediate the association between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence. Clinicians should consider screening for depressive symptoms and alcohol misuse if patients are found to be nonadherent and should treat or refer patients to appropriate resources to address those issues.

Hypertension accounts for half of the excess cardiovascular disease mortality observed in blacks. 1 Black men have a higher prevalence of hypertension, poorer blood pressure (BP) control, higher death rates due to hypertension, and increased hypertension‐related complications than non‐Hispanic whites or Hispanics, 2 , 3 even though the prevalence of BP control is improving. 4 Suboptimal antihypertensive medication aherence contributes to worse BP control and cardiovascular outcomes. Black men’s antihypertensive medication adherence is especially poor, 5 , 6 and reasons for their nonadherence are not fully known. 7 Few studies consider how psychosocial functioning may impact black men’s medication adherence.

Findings from a 5‐year randomized clinical trial designed to improve hypertension care and control among black men with uncontrolled BP living in low socioeconomic status (SES) environments in Baltimore, Maryland, provide important background on the same study population that we report on in the current manuscript. In the parent study, researchers randomized men to a more intensive educational/behavioral/pharmacologic intervention delivered by a team consisting of a nurse practitioner (NP), community health worker (CHW), and physician (MD) vs a less intensive education and referral intervention. 8 , 9 , 10 Researchers found a trend toward improved antihypertensive medication adherence in both intervention groups; however, of concern was the fact that at 5‐year follow‐up, 17% of the men in the study had died, with 36% of those deaths due to narcotic or alcohol withdrawal. Another analysis of the same study population found that depression was significantly associated with poor antihypertensive medication adherence and with alcohol use. 11 Although these researchers examined relationships between depressive symptoms, substance use, and antihypertensive medication nonadherence and found that depression was associated with worse medication adherence in bivariate analyses, they did not report results from multivariate analyses nor did they test mediating pathways of this association. 11

Many urban‐residing black men face psychosocial stressors (eg, living in impoverished, violent, and crime‐ridden neighborhoods; homelessness) 12 , 13 that can precipitate and sustain depression and adversely impact medication adherence. 14 , 15 These stressors and the coping behaviors (eg, substance use) 16 , 17 some men engage in to mitigate chronic stressors may adversely impact their medication adherence. This raised the question, which we wanted to explore further, of whether substance misuse in this population is a risk for worse medication adherence. To address limitations of previous studies, we examine direct and mediating pathways between depressive symptoms, psychosocial stressors, and substance use (both alcohol misuse and illicit drug use) on antihypertensive medication adherence in a sample of hypertensive black men enrolled in a 5‐year clinical trial. Such research is critical to development of interventions to improve antihypertensive medication adherence in hypertensive black men.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a repeated measures analysis on a sample drawn from a single‐site 5‐year randomized clinical trial of 309 hypertensive black men aged 21 to 54 years (at baseline: mean age, 41 years; >60% had a high school diploma or equivalent; 27% were employed either part‐ or full‐time; 71% reported an annual income of <$10,000; 49% did not have a regular doctor for high BP treatment; 64% reported a history of incarceration; 45% had a positive urine screen for illicit drugs; and mean systolic BP and diastolic BP were 147 ± 20 mmHg and 99 ± 15 mmHg, respectively). Hill and colleagues 8 provide additional information on the rationale for the parent study. The trial compared the effectiveness of a more intensive with a less intensive educational/behavioral/pharmacologic intervention on hypertension care and control. 9 , 10 Briefly, the more intensive intervention group received comprehensive hypertension care, including education by a NP/CHW/MD team. Visits with the NP occurred every 1 to 3 months at the Outpatient General Clinical Research Center (OPD‐GCRC). The NP made therapeutic decisions including medication titration according to guideline‐based protocol recommendations outlined in the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). 18 The CHW made at least 1 annual home visit to each participant and provided participants with need‐based referrals to social services, job training, and housing. The MD was available for consultation with the NP at the time of NP visits. The study team addressed barriers to care and free antihypertensive medication was offered to participants; however, not all men received medication (eg, men who had insurance coverage that paid for their medications). Men in the less intensive group received referral to community hypertension care sources. Men in both groups were called and reminded of the importance of BP control every 6 months and were seen at the OPD‐GCRC annually for 5 years to collect data on study outcomes.

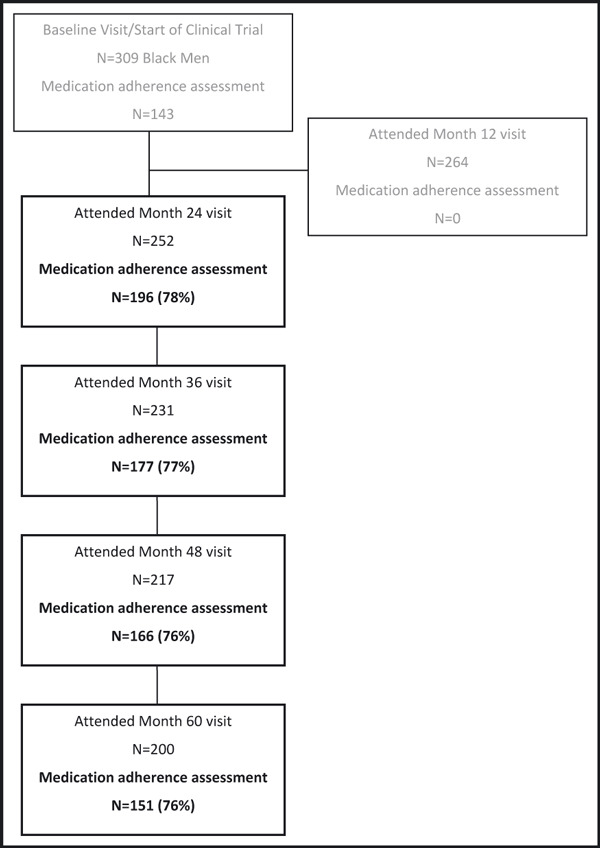

For the current analysis, the analytic sample included only clinical trial participants who attended annual study visits from months 24 to 60 and had their antihypertensive medication adherence assessed (Figure 1). Antihypertensive medication nonadherence was assessed only in men who reported being prescribed antihypertensive medication at each time period. We excluded data on antihypertensive medication nonadherence from baseline and month 12 visits because the psychosocial predictor variables of interest were not assessed at those times. For this analysis, we combined the more and less intensive intervention groups but considered intervention assignment as an effect modifier of the associations under study for some analyses.

Figure 1.

Study participant attendance and outcome assessment by study period. Study follow‐up rates account for the numbers of men who were: deceased (n=18, 34, 44, 53), incarcerated (n=14, 21, 21, 24), had moved out of state (n=6, 5, 6, 9), or were in a long‐term care facility (n=1, 2, 2, 2) at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months, respectively.

Data Collection

The team interviewed participants to collect sociodemographic and behavioral risk factors. We measured each of the variables below at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months.

Outcome. We assessed antihypertensive medication adherence using the Hill‐Bone Compliance Scale, Medication Taking subscale, which was developed in and validated for adult African American urban populations. 19 This 9‐item subscale uses a 4‐point Likert response format to assess frequency of the following BP medication‐taking behaviors: forgetting to take medication, deciding not to take medication, forgetting to get prescriptions filled, running out of medication, skipping medication, missing medication when feeling sick, missing medication when feeling better, taking someone else’s medication, and missing medication due to carelessness. The scale items were summed, resulting in a range of possible scores of 9 to 36, with higher scores indicating worse medication adherence. Given the inverse relationship between score and adherence, we hereafter refer to the outcome as antihypertensive medication “nonadherence.”

Depressive Symptoms. We used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD) scale to measure frequency of depressive symptoms. 20 CESD is a 20‐item self‐reported questionnaire that uses a 4‐point Likert response format to measure the following depressive symptoms within a 1‐week time frame: depressed mood, guilt or worthlessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances. CESD is a widely used screening tool with established reliability and validity in black populations. 21 CESD scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating increased frequency and number of depressive symptoms. A score of ≥16 is indicative of depressive symptoms and has been validated with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Third Edition criteria for clinical depression.

Psychosocial Stressors. We developed a checklist for this study, which was adapted from the Holmes and Rahe social readjustment rating questionnaire 22 and further modified based on field testing with members of the target group. For this checklist, participants reported the occurrence of 5 specific stressors: difficulty in finding a place to live, being a victim of a violent act, being involved in a major/minor law violation, getting arrested or held in jail, and separating from a spouse or partner. Participants indicated which of these stressors they experienced during the 6 months preceding each follow‐up visit (yes/no). We analyzed each stressor individually as a dichotomous variable and also examined the total number of stressors in aggregate.

Alcohol Misuse and Drug Use. Alcohol misuse was assessed with the question: “Have you ever had an alcohol‐related problem?” (yes/no). Illicit drug use was assessed using a standard urine screen for cocaine, opiates, barbiturates, cannabinoids, and/or benzodiazepines, which detected whether drug use occurred within the past 72 hours. The variable was dichotomized: 0=negative and 1=positive.

Background Variables. Guided by stress and coping 23 and behavioral models, 24 we adjusted for the following variables hypothesized or shown to be associated with antihypertensive medication adherence.

Demographic characteristics. Assessed at each time period using items from the National Health Interview Survey. 25 Marital status (married vs not married), employment status (employed vs unemployed), income (<$10,000 vs ≥$10,000 annually), and who pays for medications (private insurance vs public insurance vs other including self, family, or MD/NP provided medication samples). Age and highest educational level reported at baseline were included in the statistical models.

Systolic and diastolic BP. Measured by trained staff at the OPD‐GCRC who were blinded to group assignment using an appropriately sized cuff after the participant was seated for 5 minutes. Three BP measurements were obtained at 1‐minute intervals with a Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer. 26 The second and third BP measurements were averaged.

Tobacco use. Assessed by self‐report of current smoking (1=current smoker and 0=nonsmoker).

Usual source of care. Assessed by asking participants whether they had a regular provider for hypertension care (yes/no).

Self‐rated health. Assessed with the question, “Compared to other people your age, how would you rate your health?” Scored based on a 4‐point Likert response from 1=poor to 4=excellent.

Intervention assignment. More vs less intensive intervention groups.

Statistical Analyses

Given the longitudinal nature of these data and the fact that there were dropouts and losses to follow‐up from the clinical trial participants from which our sample was drawn, 8 , 9 , 10 we modeled whether the probability of missing outcome data were related to the following baseline variables: age, educational level, marital status, who pays for medications, employment, month, and intervention assignment. This analyses therefore controlled for biases that are not associated with the experimental manipulations that may affect the probability of missingness (eg, whether due to dropout or death). We could not assess whether missingness was associated with any variables that were not obtained at baseline (eg, depression and alcohol misuse). The probability of missing data was significantly related to month (P=.05) and marital status (.04). Therefore, we used a weighted estimating equation approach. 27 In this approach, each person‐visit was weighted inversely proportional to their probability of being observed. We then conducted repeated measures analyses with Weighted Generalized Estimating Equations using PROC GENMOD (SAS 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) examining psychosocial and behavioral predictors of antihypertensive medication nonadherence at each study period from 24 to 60 months. We built a series of models: the first modeled the relationships between the background variables and antihypertensive medication nonadherence. Subsequent models were then built with the addition of the following independent variables: depressive symptoms (model 2); psychosocial stressors (model 3); alcohol misuse (model 4); illicit drug use (model 5); and depressive symptoms, psychosocial stressors, alcohol misuse, and illicit drug use (model 6). For independent variables that were found to be significantly associated with antihypertensive medication nonadherence, we examined whether those associations were moderated by intervention group. To this end, we conducted separate models testing the main and interaction effects on antihypertensive medication nonadherence between intervention group and the variable of interest. 28

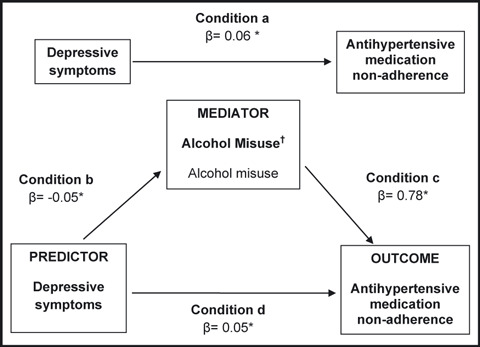

We conducted mediation analyses using hierarchical Generalized Estimating Equations (SAS PROC GENMOD) according to the mediational analytic framework described by Baron and Kenny to determine whether alcohol misuse mediates the association between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence. 28 In this approach, mediation exists when 4 conditions are met: (1) the predictor variable (ie, depressive symptoms) is significantly related to the outcome variable (antihypertensive medication nonadherence), (2) the hypothesized mediator (ie, alcohol misuse) is significantly related to the predictor variable, (3) the mediator is significantly related to the outcome, and (4) the relationship between the predictor and the outcome variables is significantly reduced when controlling for the mediator. We ran 4 regression models to estimate the relative effect size using unstandardized beta coefficients (β) needed to satisfy the 4 mediation criteria. We formally tested mediation effect using Sobel’s mediation test. 29

Results

Sample Characteristics by Study Period

Sample sizes from months 24, 36, 48, and 60 were 196, 177, 166, and 151, respectively. Table I displays sample characteristics across study periods. Briefly, the mean highest educational level was about 11 years, about 20% were married, and the majority did not have insurance to cover their medications. About half of the sample had good self‐rated health, most were current smokers, and approximately 40% to 50% had a positive urine screen for illicit drugs. Mean systolic and diastolic BP over time was about 141 mm Hg and 90 mm Hg. During the study period, between 26% and 32% had depressive symptoms and 20% to 24% endorsed ever having had an alcohol‐related problem.

Table I.

Sample Characteristics by Study Period

| Characteristic | Sample Mean±Standard Deviation or No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 24 (N=196) | Month 36 (N=177) | Month 48 (N=166) | Month 60 (N=151) | |

| Background/control variables | ||||

| Age, y | 41.7 ± 5.6 | 42.3 ± 5.4 | 42.0 ± 5.6 | 41.9 ± 5.6 |

| Education, y | 11.4 ± 2.0 | 11.4 ± 2.2 | 11.6 ± 2.2 | 11.6 ± 2.0 |

| Currently married (vs not married) | 37 (19) | 36 (20) | 35 (21) | 34 (23) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 142.7 ± 19.2 | 140.9 ± 21.3 | 140.1 ± 21.0 | 141.8 ± 23.5 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 87.9 ± 12.5 | 89.8 ± 14.1 | 91.0 ± 13.8 | 93.4 ± 16.0 |

| Who pays for medications | ||||

| Private | 39 (20) | 36 (20) | 30 (18) | 27 (18) |

| Public | 43 (22) | 37 (21) | 27 (16) | 21 (14) |

| Other (including self, family, or samples provided by MD or NP) | 113 (58) | 103 (59) | 108 (65) | 101 (68) |

| Self‐rated health | ||||

| Poor | 12 (6) | 7 (4) | 8 (5) | 7 (5) |

| Fair | 51 (6) | 44 (26) | 41 (25) | 36 (24) |

| Good | 91 (48) | 86 (50) | 78 (48) | 71 (48) |

| Excellent | 37 (19) | 35 (20) | 34 (21) | 33 (22) |

| Current smoker (vs nonsmoker) | 138 (73) | 118 (67) | 109 (66) | 95 (63) |

| Urine screen positive for Illicit drugs | 90 (49) | 75 (43) | 67 (41) | 56 (39) |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

| CESD score | 10.9 ± 8.1 | 11.4 ± 9.4 | 10.9 ± 9.5 | 12.7 ± 11.5 |

| CESD ≥16 | 54 (28) | 46 (26) | 43 (26) | 48 (32) |

| Psychosocial stressors (in past 6 months) | ||||

| Victim of violent act | 15 (8) | 0 (0) | 10 (6) | 8 (5) |

| Major or minor law violation | 13 (7) | 6 (3) | 12 (7) | 10 (7) |

| Arrested or held in jail | 16 (8) | 6 (3) | 14 (8) | 9 (6) |

| Difficulty in finding a place to live | 14 (7) | 6 (3) | 20 (12) | 14 (9) |

| Separated spouse or partner | 13 (5) | 12 (5) | 31 (14) | 20 (10) |

| Employed (vs unemployed) | 71 (36) | 68 (38) | 61 (37) | 64 (42) |

| Alcohol misuse | ||||

| Ever had an alcohol‐related problem (vs not) | 39 (20) | 37 (21) | 40 (24) | 36 (24) |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; MD, physician; NP, nurse practitioner.

Effects of Time on Antihypertensive Medication Nonadherence

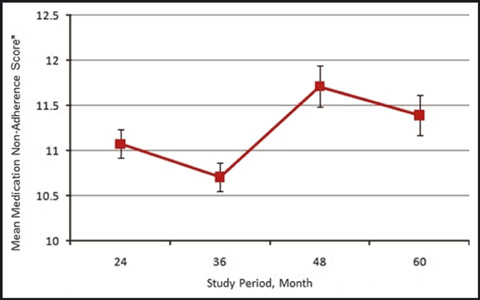

The mean (standard deviation) antihypertensive medication nonadherence scores at months 24, 36, 48, and 60 were 11.1 (2.6), 10.6 (2.2), 11.7 (3.3), and 11.7 (2.9), respectively (Figure 2). Given the possible range in medication nonadherence scores of 9 to 27, these scores indicate generally low medication nonadherence (ie, good adherence). Compared with month 24, there was significantly less medication nonadherence at 36 months (β=−0.37; standard error [SE], 0.16; P=.02) and more nonadherence at 48 months (β=0.64; SE, 0.22; P<.01).

Figure 2.

Mean adherence score using Hill‐Bone Compliance Scale, Medication Taking subscale, during study period. *Lower scores indicate better medication adherence.

Main Effects of Depressive Symptoms, Psychosocial Stressors, Alcohol Misuse, and Illicit Drug Use on Antihypertensive Medication Nonadherence

Of the background variables examined, only study period and intervention assignment were significantly related to antihypertensive medication nonadherence (Table II, model 1). After adjustment for background variables, greater depressive symptoms were associated with more nonadherence (β=0.05; SE, 0.01; P<.001) (Table II, model 2). None of the psychosocial stressor variables were associated with antihypertensive medication nonadherence (Table II, model 3), although there was a trend toward more nonadherence for men who were separated from a spouse or partner (β=0.85; SE, 0.47; P=.07). Of note, there was a significant correlation between the number of psychosocial stressors and the total depressive symptom score (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.23; P<.0001). Answering “yes” to ever having had an alcohol‐related problem was associated with more medication nonadherence (β=0.81; SE, 0.26; P<.01) than answering “no” (Table II, model 4). Illicit drug use was not significantly associated with worse medication nonadherence (Table II, model 5). When we included depressive symptom, psychosocial stressors, alcohol misuse, and illicit drug use in the same multivariate model to assess independent associations with antihypertensive medication nonadherence (Table II, model 6), depressive symptoms and alcohol misuse remained significantly associated with medication nonadherence.

Table II.

Linear Association Between Independent Variables and Antihypertensive Medication Nonadherence

| β Coefficient | Standard Error | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: background characteristicsa | |||

| Month 24 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Month 36 | −0.28 | 0.16 | .07 |

| Month 48 | 0.69 | 0.23 | <.01 |

| Month 60 | 0.29 | 0.21 | .15 |

| Less intensive intervention group | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| More intensive intervention group | −0.73 | 0.32 | .02 |

| Model 2: depressive symptomsb | |||

| Depression score | 0.05 | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Model 3: psychosocial stressorsb | |||

| Victim of a violent act within past 6 months | −0.50 | 0.39 | .21 |

| Major or minor law violation within past 6 months | 0.17 | 0.41 | .69 |

| Been arrested or held in jail within past 6 months | 0.22 | 0.43 | .60 |

| Difficulty in finding a place to live within past 6 months | 0.31 | 0.40 | .43 |

| Separated from spouse or partner within past 6 months | 0.85 | 0.47 | .07 |

| Model 4: alcohol misuseb | |||

| Answered “yes” to ever having had an alcohol‐related problem | 0.81 | 0.26 | <.01 |

| Model 5: Negative urine screen for illicit drugs | 0.04 | 0.20 | .84 |

| Model 6: depressive symptoms, psychosocial stressors alcohol misuse, and illicit drug useb | |||

| Depression score | 0.04 | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Victim of a violent act within past 6 months | −0.71 | 0.41 | .09 |

| Major or minor law violation within past 6 months | −0.09 | 0.40 | .82 |

| Been arrested or held in jail within past 6 months | 0.21 | 0.43 | .62 |

| Difficulty in finding a place to live within past 6 months | 0.22 | 0.41 | .58 |

| Separated from spouse or partner within past 6 months | 0.85 | 0.45 | .06 |

| Alcohol misuse | 0.70 | 0.27 | .01 |

| Negative urine screen for illicit drugs | 0.10 | 0.20 | .60 |

aNone of the following other background characteristics adjusted for were significantly associated with hypertension medication nonadherence at P<.10 level: age, education, who pays for medications, marital status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, current smoking, and self‐rated health. bAdjusted for background characteristics.

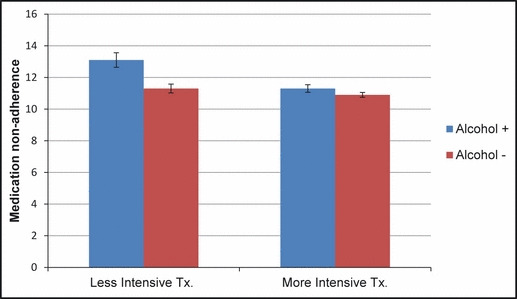

Mediation and Effect Modification

Alcohol misuse did not mediate the association between depressive symptoms and antihypertensive medication nonadherence (β for condition “a” 0.06, P<.001; β for condition “d” 0.05, P<.001) (see Figure 3). Since neither illicit drug use nor psychosocial stressors were significantly associated with antihypertensive medication nonadherence, they did not meet criteria to be considered mediators of the association between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence. There was evidence of effect modification by intervention group on the relationship between reporting having had an alcohol‐related problem and antihypertensive medication nonadherence (β for interaction of intervention group × alcohol‐related problem was 1.56 (SE 0.55, P<.01) (Figure 4). Among men in the less intensive group, those who reported having an alcohol‐related problem were more nonadherent than those who did not report an alcohol‐related problem (P<.01). In contrast, among men in the more intensive group, levels of antihypertensive medication nonadherence did not differ as a function of their history of ever having an alcohol‐related problem (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Mediational model showing both the direct and the mediated pathways by which depressive symptoms influence antihypertensive medication nonadherence.

Figure 4.

Effect modification by intervention group of association between alcohol misuse and antihypertensive medication nonadherence.

Discussion

We examined direct and mediating pathways between depressive symptoms, psychosocial stressors, and substance use (both alcohol misuse and illicit drug use) on antihypertensive medication nonadherence in a sample of hypertensive black men enrolled in a clinical trial to improve HBP care and control. As hypothesized, we found that more depressive symptoms and alcohol misuse were associated with increased antihypertensive medication nonadherence over a 3‐year period. Alcohol misuse did not mediate the association between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence. Contrary to our hypothesis, neither psychosocial stressors nor illicit drug use were significantly related to antihypertensive medication nonadherence and therefore neither were mediators of the association between depressive symptoms and antihypertensive medication nonadherence. Overall, self‐reported antihypertensive medication nonadherence scores varied over time.

Our finding that more depressive symptoms were associated with antihypertensive medication nonadherence is consistent with results from other studies. 7 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 While this finding is not novel, our study makes a unique contribution to the literature for several reasons. By using a prospective design we were able to document the consistency of this association over time. Further, our work highlights the chronicity of depressive symptoms and their effects on antihypertensive medication nonadherence in black men specifically. This is important since other studies had an under‐representation of black men 30 , 31 or primarily targeted older adults. 32

Our work supports findings from at least one other study that showed an association between alcohol misuse and antihypertensive medication nonadherence. 37 However, we did not find that alcohol misuse mediates the association between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence. Kim and colleagues 11 examined relationships between depressive symptoms, alcohol misuse, and antihypertensive medication nonadherence using the same study population as the current study, but they did not specifically examine alcohol misuse as a mediator. Because we did not find any other studies that examined the relationships between depressive symptoms, alcohol misuse, and antihypertensive medication nonadherence, we cannot compare our findings with previous research. The mechanisms by which depressive symptoms affect medication adherence are unclear and likely complex. Some potential mechanisms include decreased self‐care, decrements in memory and cognition, intentional self‐harm, and reduced self‐efficacy. Future studies should assess other potential mediating factors in hypertensive black men to guide intervention development.

We found that the effect of alcohol misuse on antihypertensive medication nonadherence differs by intervention group. Among men in the less intensive group, those who reported ever having an alcohol‐related problem were more nonadherent than those who did not report ever having an alcohol‐related problem. The interaction between alcohol misuse and intervention group might explain why we failed to find a significant mediation effect for alcohol misuse on the association between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence. It is possible that alcohol misuse interacts with depressive symptoms to adversely affect antihypertensive medication adherence only among men with fewer resources and sources of positive support (ie, men in the less intensive intervention group). Men in the more intensive group may have had other resources, even in the face of depressive symptoms, which helped to combat the potentially negative impact of alcohol misuse on their ability to adhere to their antihypertensive medications.

Study Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, we used self‐reported responses to assess antihypertensive medication nonadherence. Although some studies demonstrate moderate to strong concordance between self‐reported medication adherence and pharmacy refill data, 38 , 39 other studies have shown that self‐reported adherence does not correlate well with objective measures. Furthermore, there was little variability in antihypertensive medication nonadherence scores. The lack of spread in this variable may make it difficult to identify significant correlations with other variables and may bias our findings toward the null. Future studies should assess antihypertensive medication nonadherence both subjectively and objectively. Second, since our analysis started at month 24, we did not examine associations between the predictor variables of interest and medication nonadherence at baseline. It is also possible that the intervention itself may have changed the level of some of our predictor variables (eg, depressive symptoms and psychosocial stressors). Third, we did not use a validated questionnaire, such as the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test‐Consumption (AUDIT‐C), 40 to assess alcohol misuse. Our single item question, “have you ever had an alcohol‐related problem” does not differentiate individuals along the spectrum from “risky drinking” to “alcohol abuse and dependency.” Our question is a proxy for alcohol misuse that assesses any history of alcohol misuse rather than current alcohol misuse, which would be more appropriate and closely related to current medication nonadherence. Fourth, we used a nonvalidated measure of psychosocial stressors and limited response options to yes/no for each life event. While our approach may have reduced respondent burden, it may have resulted in measurement error and an inability to detect statistically significant associations. Finally, the external validity of our findings may be limited since our sample included black men of relatively low socioeconomic status who resided in Baltimore and were enrolled in a clinical trial.

Study Strengths

Despite these limitations, our study has strengths. It was theoretically grounded and we empirically tested direct and mediating mechanisms for the known association between depressive symptoms and antihypertensive medication nonadherence. Further, we examined this clinically important issue in a sample of black men—a highly underrepresented population in research. We screened for the presence of depressive symptoms using a validated instrument. Finally, we used a prospective design that allowed us to examine antihypertensive medication nonadherence and psychosocial factors over time.

Conclusions

Our study has important implications for clinical practice and research. The findings extend our understanding of psychosocial factors that might limit the effectiveness of hypertension treatment by interfering with medication adherence in a high‐risk population of black men. Given the strong and persistent association of depressive symptoms and alcohol misuse with antihypertensive medication nonadherence, clinicians should consider routine and ongoing screening for depressive symptoms and alcohol misuse in hypertensive black men who are nonadherent with their antihypertensive medications. Clinicians and researchers interested in improving hypertension control and cardiovascular outcomes through better medication adherence should continue to investigate and intervene on the myriad psychosocial factors operant in the lives of black men that adversely impact their ability to adhere to therapy. Future research should examine whether identifying and treating depression and alcohol misuse disorders in black men improves medication adherence and ultimately BP control and cardiovascular outcomes.

Disclosures: Dr Cené received support as a funded scholar through the Clinical Translational Science Award‐K12 Scholars Program (KL2). The CTSA is a national consortium with the goal of transforming how clinical and translational research is conducted, ultimately enabling researchers to provide new treatments more efficiently and quickly to patients. Dr Cené’s work on this project was supported by award number KL2RR025746 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, as well as by award number K23HL107614 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the NIH. Dr Powell Hammond receives research and salary support from the UNC Cancer Research Fund, National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities (award No. 1L60MD002605‐53401), and National Cancer Institute (grant No. 3U01CA114629‐04 S2). Drs Dennison, Levine, and Hill and Ms Bone were supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research and NIH (K08 NR00049), the Johns Hopkins Outpatient General Clinical Research Center, and the JM Foundation, Hoechst Marion Roussel, and W.A. Baum Co.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: We presented earlier versions of this manuscript as presentations at the 48th American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology and Prevention Annual Conference in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in 2008 and at the Society of General Internal Medicine National Meeting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 2008.

References

- 1. Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States 2008 with Chartbook. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , ed. A Closer Look at African American Men and High Blood Pressure Control: A Review of Psychosocial Factors and Systems‐Level Interventions. Altanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2008;52:818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hyre AD, Krousel‐Wood MA, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence and predictors of poor antihypertensive medication adherence in an urban health clinic setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark LT. Improving compliance and increasing control of hypertension: needs of special hypertensive populations. Am Heart J. 1991;121:664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewis LM. Factors associated with medication adherence in hypertensive blacks: a review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27:208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hill MN, Han HR, Dennison CR, et al. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:906–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hill MN, Bone LR, Hilton SC, et al. A clinical trial to improve high blood pressure care in young urban black men: recruitment, follow‐up, and outcomes. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dennison CR, Post WS, Kim MT, et al. Underserved urban african american men: hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim MT, Han HR, Hill MN, et al. Depression, substance use, adherence behaviors, and blood pressure in urban hypertensive black men. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DiPietro B, Kimball R, Gillis L. Baltimore City 2005 Census: The Picture of Homelessness. The Abell Foundation: Baltimore Homeless Services, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baltimore County Health Department . Baltimore City vital statistics profile 2005. http://www.baltimorehealth.org/info/BaltimoreVitalStats2005.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2010.

- 14. Han HR, Kim MT, Rose L, et al. Effects of stressful life events in young black men with high blood pressure. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis LM, Schoenthaler AM, Ogedegbe G. Patient factors, but not provider and health care system factors, predict medication adherence in hypertensive black men. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14:250–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jackson JS, Knight KM. Race and self‐regulatory behaviors: the role of the stress response and the HPA axis in physical and mental health disparities. In: Schaie KW, Carstensen CC, eds. Social Structure, Aging, and Self‐Regulation in the Elderly. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:198–204. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:933–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim MT, Hill MN, Bone LR, Levine DM. Development and testing of the Hill‐Bone Compliance to High Blood Pressure Therapy Scale. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2000;15:90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Radloff LS. The CES‐D scale: a self‐report scale for research in general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyon DE, Munro C. Disease severity and symptoms of depression in Black Americans infected with HIV. Appl Nurs Res. 2001;14:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;2:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Health Interview Survey . National Center for Health Statistics: Survey Questionnaires. Hyattsville, MD: National Health Interview Survey; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prineas RJ, Harland WR, Janzon L, Kannel W. Recommendations for use of non‐invasive methods to detect atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease – in population studies. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology. Circulation. 1982;65:1561A–1566A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Preisser JS, Lohman KK, Rathouz PJ. Performance of weighted estimating equations for longitudinal binary data with drop‐outs missing at random. Stat Med. 2002;21:3035–3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator‐mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang PS, Bohn RL, Knight E, et al. Noncompliance with antihypertensive medications: the impact of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Siegel D, Lopez J, Meier J. Antihypertensive medication adherence in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Med. 2007;120:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krousel‐Wood M, Islam T, Muntner P, et al. Association of depression with antihypertensive medication adherence in older adults: cross‐sectional and longitudinal findings from CoSMO. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:248–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G, Allegrante JP. Self‐efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braverman J, Dedier J. Predictors of medication adherence for African American patients diagnosed with hypertension. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lewis LM, Askie P, Randleman S, Shelton‐Dunston B. Medication adherence beliefs of community‐dwelling hypertensive African Americans. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bautista LE, Vera‐Cala LM, Colombo C, Smith P. Symptoms of depression and anxiety and adherence to antihypertensive medication. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, et al. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rickles NM, Svarstad BL. Relationships between multiple self‐reported nonadherence measures and pharmacy records. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2007;3:363–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krousel‐Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, et al. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: perspective of the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:753–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT‐C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]