Abstract

Block copolymer silver nanoparticle composite elastic conductors were fabricated through solution blow spinning and subsequent nanoparticle nucleation. The reported technique allows for conformal deposition onto nonplanar substrates. We additionally demonstrated the ability to tune the strain dependence of the electrical properties by adjusting nanoparticle precursor concentration or localized nanoparticle nucleation. The stretchable fiber mats were able to display electrical conductivity values as high as 2000 ± 200 S/cm with only a 12% increase in resistance after 400 cycles of 150% strain. Stretchable elastic conductors with similar and higher bulk conductivity have not achieved comparable stability of electrical properties. These unique electromechanical characteristics are primarily the result of structural changes during mechanical deformation. The versatility of this approach was demonstrated by constructing a stretchable light emitting diode circuit and a strain sensor on planar and nonplanar substrates.

Keywords: flexible electronics, block copolymer composite, nanocomposite, stretchable conductor, solution blow spinning

Stretchable conductor research has expanded significantly due to interest in mechanically deformable circuitry for use in flexible electronics. Such materials have applications in stretchable displays,1 solar cells,2 field effect transistors,3 radio frequency antennas,4 strain and tactility sensors,5−8 and epidermal electronics.9−13 Current approaches use assemblies of conductive and elastomeric components to produce materials that maintain electrical properties under strain. However, the mechanical properties of the conductive component often cause a decrease in elasticity when composites reach high electrical conductivities.14

Stretchable conductors have been demonstrated using networks of nanowires or nanotubes backfilled with elastomers,15−18 polymer nanoparticle composites,19,20 liquid metal filled elastomeric channels,4,21−23 conductive networks on prestrained or buckled substrates,24,25 and metallic fractal or microwire patterns on polymer substrates.9,26 Metallic nanowire and carbon nanotube based materials have shown mechanical and electrical robustness under cyclic deformation.16,17 However, when these systems reach high conductivities there is a significant reduction in maximum tensile strain due to increased rigid filler content.17,27 Polymer nanoparticle composites have demonstrated enhanced mechanical elasticity and high conductivity, but require higher filler content when compared to nanowire and nanotube based materials with similar conductivities.19 Elastomers containing channels of liquid metal compromise overall material strength due to the inherent mechanically poor nature of the conductive component. Metallic patterns are able to maintain the bulk electrical properties of the conductive component under strain with limitations for the ultimate achievable strain values originating from the pattern geometry.9

Another important consideration in the development of elastic conductors is the ease of fabrication and deposition of the material onto nonplanar substrates. This is particularly important for applications such as epidermal electronics9 and smart textiles.28 Current methodologies utilize complex lithographical methods,29−32 printing,33−35 or spray techniques6 and require transfer from a planar fabrication substrate to a nonplanar substrate of interest. These methods have been utilized to transfer flexible electronic devices onto a variety of contoured substrates such as concave,29 convex,36,37 and other curved surfaces.11,32 The deformation that occurs when a planar elastic conductor is placed conformally onto a nonplanar substrate leads to degradation of the material’s electrical properties.37 To our knowledge, direct deposition of stretchable conductors on nonplanar substrates has not yet been demonstrated.

Here we report a method to fabricate highly conductive elastic composites with electrical properties that vary minimally under high levels of strain. This fabrication process allows for conformal deposition on nonplanar substrates utilizing a combination of solution blow spinning38 and spray coating or printing. The deposition process is direct and does not require transfer from a separate substrate. The resulting stretchable conductor consists of an elastomeric fiber mat silver nanoparticle composite. Initially, a fiber mat is blow spun from a solution of poly(styrene-block-isoprene-block-styrene) (SIS) block copolymer in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (Figure 1). To establish conductivity, a silver precursor solution is applied to a prespun mat and is nucleated into a network of silver nanoparticles, forming conductive pathways. The resulting composite achieves a conductivity of 2000 ± 200 S/cm at zero applied strain, with only a 12% increase in resistance after 400 cycles at 150% strain. These stable electrical properties are attributed to conductive pathways maintained through silver nanoparticle stabilized fiber-to-fiber contacts and strain induced structural changes. We have also demonstrated the ability to tune the strain dependence of the electrical properties by adjusting nanoparticle precursor concentration or localized nanoparticle nucleation. The versatility of this approach was demonstrated by constructing a stretchable light emitting diode (LED) circuit and a strain sensor on planar and nonplanar substrates.

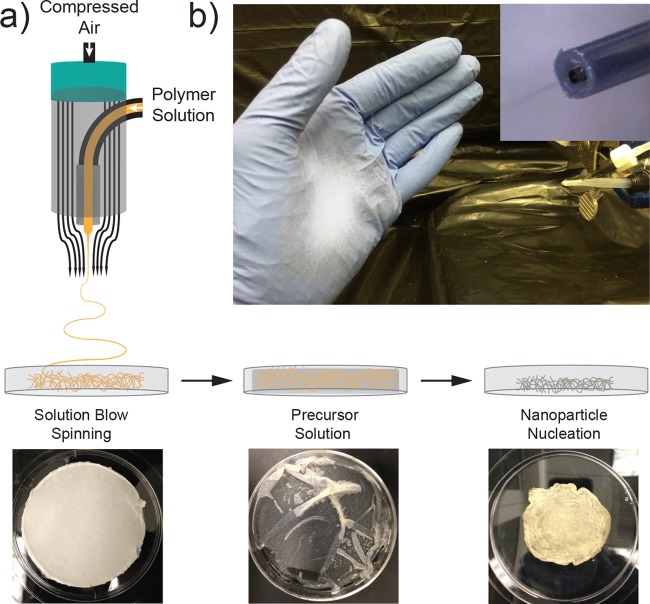

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of poly(styrene-block-isoprene-block-styrene) (SIS) block copolymer solution blow spun fiber network fabrication and images of the as-spun fiber network, fiber mat swollen with silver nanoparticle precursor solution, and conductive polymer nanoparticle composite after nanoparticle nucleation. (b) Image of the direct deposition of SIS fibers onto a gloved hand (solution blow spinning nozzle in use-inset).

Results and Discussion

The process of block copolymer nanoparticle composite fabrication consists of elastomeric fiber mat deposition, introduction of silver nanoparticle precursor, and nanoparticle nucleation (Figure 1a). Solution blow spinning was used to generate nonwoven block copolymer fiber mats, allowing for rapid deposition on nonplanar substrates (Figure 1b).38−40 This technique requires only a simple apparatus, high-pressure gas source, and a concentrated polymer solution in a volatile solvent.38 Analogous to other solution-processed spinning techniques, fiber generation is achieved above a critical solution concentration, corresponding to polymer chain overlap.41 An elastomeric block copolymer was utilized because the presence of the rigid block, in this case polystyrene, allows the material to remain structurally stable without cross-linking. Upon the introduction of the silver nanoparticle precursor solution, fiber mats swell and become translucent. This is indicative of a preferable interaction between nanoparticle precursor and polymer, as swelling does not take place when solvent alone is introduced. This affinity is explained by the specific interactions of transition metal ions with unsaturated hydrocarbons, such as the double bonds on isoprene, that form weak charge-transfer complexes.42 Finally, nanoparticles are nucleated through reduction of the silver ions associated with isoprene creating a conductive composite.

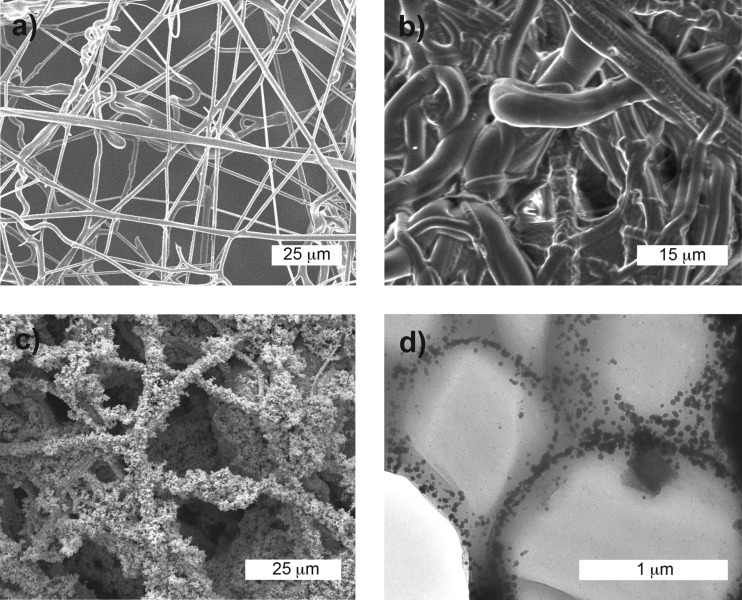

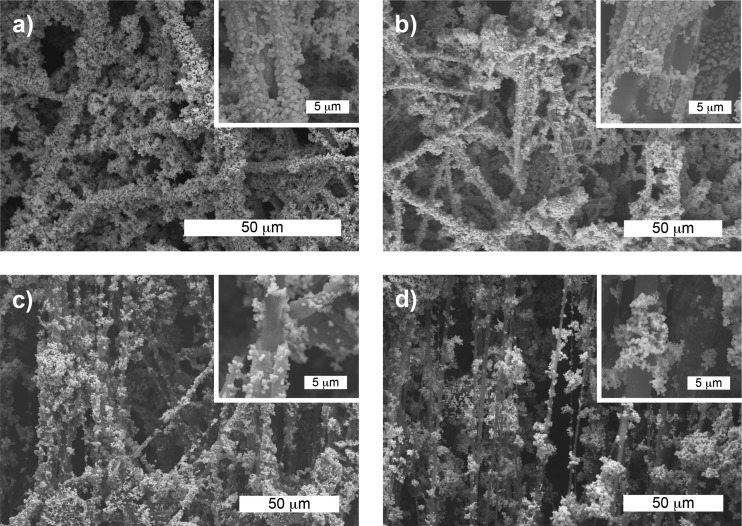

Microstructure characterization by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that a fiber network structure was achieved for SIS/THF solutions with a concentration of 20% (wt/vol) (Figure 2a). The average diameter of elastomeric fibers after spinning was 1.66 ± 0.70 μm as measured by SEM. This network structure, consisting of high aspect ratio cylindrical fibers, facilitates homogeneous nanoparticle distribution. The fiber mats were swollen in silver nanoparticle precursor solution containing various concentrations of silver trifluoroacetate (STFA) in ethanol. Through this process the fiber diameter increased to an average of 3.28 ± 1.51 μm and fiber-to-fiber contact was enhanced by the formation of additional fiber junctions (Figure 2b). Hydrazine hydrate solution was then used to reduce the silver ions in the precursor-swollen mats, forming silver nanoparticles with an average diameter of 37.6 ± 14.2 nm as measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Individual fiber diameter decreased in comparison to the swollen state and bound fiber-to-fiber connections were stabilized with nanoparticles subsequent to their nucleation (Figure 2c). TEM of the silver nanoparticle polymer fiber composite cross-section revealed that nanoparticles populate the outer surface of fibers (Figure 2d). Styrene content also had a major effect on composite morphology. A fiber mat fabricated with 14 wt % styrene SIS irreversibly lost fiber morphology during precursor swelling and nanoparticle nucleation (Figure S2, Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

(a) SEM images of SIS blow spun fiber network, (b) swollen with silver precursor solution, (c) conductive composite decorated with silver nanoparticles, (d) cross-section TEM image of conductive block copolymer nanoparticle composite fibers.

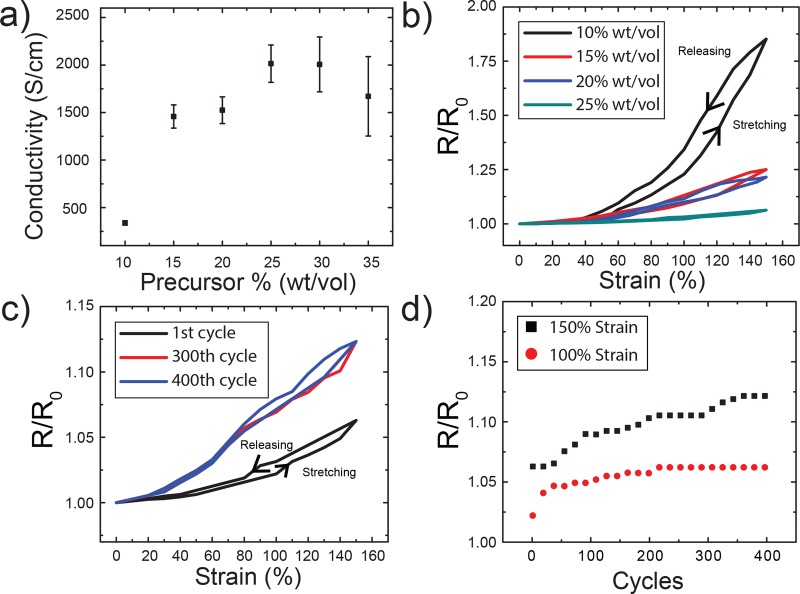

The nanoparticle precursor solution concentration effect on conductivity was assessed by measuring bulk conductivity of the polymer nanoparticle composites (Figure 3a). Maximum conductivity values (∼2000 S/cm) were achieved with a precursor concentration range between 25% and 35% (wt/vol). Fabrication of composites with 30% and 35% (wt/vol) STFA solutions led to increased variability in conductivity, 2000 ± 300 S/cm and 1700 ± 400 S/cm, respectively. This variability can be attributed to trapped nitrogen gas formed during the nucleation reaction that creates voids and results in fiber mat delamination and structural heterogeneity. This was further reflected in elastic recovery experiments, where these materials yielded before completing cycling up to 150% strain (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Materials fabricated with 25% (wt/vol) and lower STFA solutions all survived cycling to 150% strain with no significant difference between the elastic recovery of conductors fabricated with 25% (wt/vol) STFA solution and SIS fiber mats (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Electrical properties under cyclic strain were characterized for conductive composites. Precursor concentration markedly influenced electromechanical behavior. The normalized resistance (R/R0) values of polymer nanoparticle composites fabricated with 10% (wt/vol) STFA solutions reach 1.85 at 150% strain with appreciable hysteresis beginning at 40% strain (Figure 3b). When STFA concentration is increased to 25% (wt/vol) normalized resistance at 150% strain decreases to 1.06 with a significant reduction in hysteresis after a single cycle (Figure 3b). This stable electrical behavior under strain was additionally observed by a minimal resistance increase after 400 cycles of 100% (R/R0 = 1.06) and 150% strain (R/R0 = 1.12) (Figure 3c,d). Stretchable conductors with similar and higher bulk conductivity have not achieved comparable stability of electrical properties under mechanical deformation ((σ0/σ = 4.0, σ0 = 1670 S/cm, 150% strain),43 (σ0/σ = 4.6, σ0 = 11000 S/cm, 110% strain),19 (σ0/σ = 8.9, σ0 = 5400 S/cm, 140% strain)20). Additionally, the resistance of the conductive composites at 0% strain remains unchanged with repetitive deformation (Figure 3c). This indicates that changes in electrical properties are recoverable when undergoing strain cycling up to 150% strain. In order to evaluate the influence of the fiber network on the electromechanical properties, conductive SIS films were fabricated via drop casting, swollen with silver precursor, and nucleated. The electrical conductivity of these films is lost before reaching 55% strain, which is prior to mechanical failure of the film (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

(a) Average electrical conductivity of stretchable conductors as a function of STFA concentration. (b) Normalized resistance values as a function of uniaxial tensile strain for various STFA concentrations. (c, d) Normalized resistance values as a function of uniaxial tensile strain and cycle number.

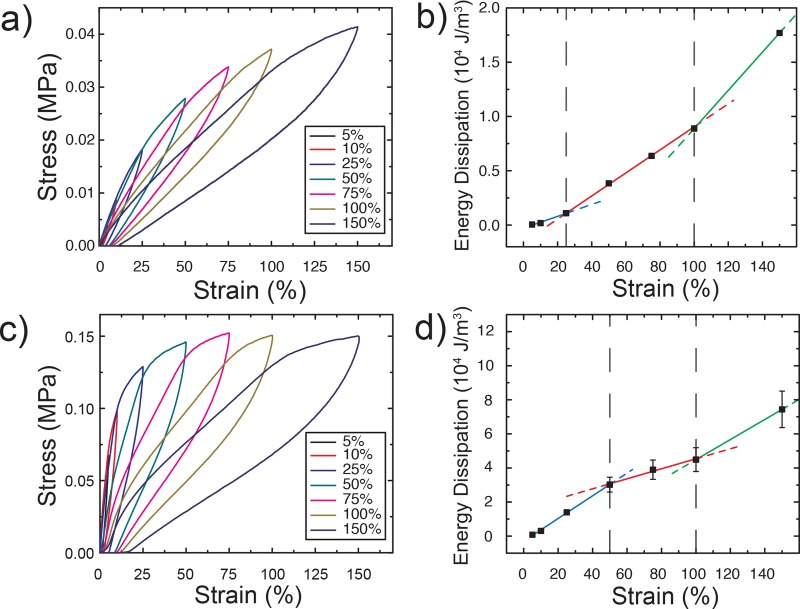

We believe the electromechanical characteristics of the elastomeric fiber based conductors are primarily the result of structural changes during mechanical deformation. To investigate this influence, energy dissipation was calculated from the area of the hysteresis loops of cyclic stress/strain curves for both SIS fiber mats and conductive composites (Figure 4 and Figure S5, Supporting Information). This analysis revealed the presence of three distinct regions corresponding to strain induced structural changes (Figure 4b,d). These regions were determined using linear correlations relating energy dissipation to strain. Changes in slope are indicative of a structural transition. In SIS fiber mats, increasing strain led to an increase in slope after each transition. At strain levels below 25%, minor structural changes occur in which fibers rearrange. Bound fiber connections break when strain values increase to greater than 25%. These connections are known to contribute significantly to the mechanical strength of elastomeric fiber mats.44,45 As strain values continue to increase to above 100% strain, individual fibers begin to deform. Different strain dependent mechanical properties are evident in the conductive composites. In contrast to the pure SIS fiber mats, large changes in dissipative losses occur at strains below 50%. These large changes possibly stem from breakage of silver nanoparticle reinforced fiber junctions. At strain values beyond 50%, diminishing influence of these reinforced junctions allow fibers to rearrange. Fiber rearrangement results in less drastic changes in energy dissipation for strain values between 50 and 100%. At strains values above 100%, individual fibers deform and silver nanoparticle coverage becomes discontinuous. This results in an increased rate of dissipative loss at high strain values.

Figure 4.

(a) Stress/strain cycling curves and (b) average energy dissipation values and corresponding linear fits for pure SIS fiber mats. (c) Stress/strain cycling curves and (d) average energy dissipation values and corresponding linear fits for elastic conductors fabricated with 25% (wt/vol) STFA solutions. Linear correlations relating energy dissipation to strain describe different regions of strain induced structural changes (blue, red, and green lines).

The described structural changes were confirmed by imaging conductive composites at region-specific strain values of 0%, 50%, 100%, and 150% (Figure 5). At 50% strain, there are no discernible changes in structure except for breakage at silver nanoparticle reinforced fiber junctions (Figure 5b, inset). As strain is increased to 100% fibers are able to rearrange in the direction of applied strain (Figure 5c). At strain values exceeding 100%, fibers elongate and the silver nanoparticle coating becomes intermittent (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

SEM images of conductive composites fabricated using 25% (wt/vol) STFA solutions under (a) 0% strain, (b) 50% strain, (c) 100% strain, and (d) 150% strain. Higher magnification SEM images of individual fibers for respective conductive composites under different strain values are provided in the inset.

Structural and mechanical analysis of the conductive composites is in agreement with the previously described electromechanical properties. The onset of hysteresis in electrical properties during initial mechanical deformation is concurrent with structural changes originating from fiber rearrangement (Figure 3b,c). Structural rearrangement in the direction of applied strain has been previously shown to cause electrical hysteresis in conductive elastomer nanocomposites due to anisotropic network deformation that leads to a decrease in conductive component connectivity.46 While undergoing cyclic strain testing to 150%, strain dependence of electrical properties increases up to the 300th cycle as fibers irreversibly deform. After the 300th cycle, electrical properties stabilize due to the previously incurred plastic deformation (Figure 3c). This is also reflected in Figure 3d, where normalized resistance values for the conductive composite increase as a function of cycle number until reaching the 300th cycle of 150% strain. Fibers do not irreversibly deform If only cycled to 100% strain. Fiber rearrangement causes initial increases in normalized resistance values, resulting in electrical property stabilization after the 50th cycle (Figure 3d). When strained beyond 150%, electrical properties rapidly deteriorate, reaching a normalized resistance value of 81.1 at mechanical failure (∼400% strain, Figure S6, Supporting Information).

Using the described approach for depositing and patterning elastic conductors on nonplanar surfaces requires three separate deposition steps and compatibility considerations. The solution blow spun elastomeric fibers must first adhere to the substrate of interest. SIS and other styrene block copolymers, in combination with other additives, have been investigated and used as adhesives.47,48 The physically anchored block copolymer structure combines low elastic modulus (isoprene block) and creep resistance (styrene block) imparting inherent adhesiveness to SIS.47,49 Solution blow spun SIS fiber mats adhered to a variety of substrates, including glass, metal mesh, silicon wafer, polystyrene, and aluminum foil. The second major consideration regarding direct deposition and patterning through spray coating or printing is solvent and chemical compatibility. Ethanol-sensitive substrates, such as polymers containing hydroxyethyl methacrylate or vinylpyridine, could deform during nanoparticle precursor application. During nucleation, hydrazine reactive substrates, such as polyesters, could be damaged through aminolysis.50

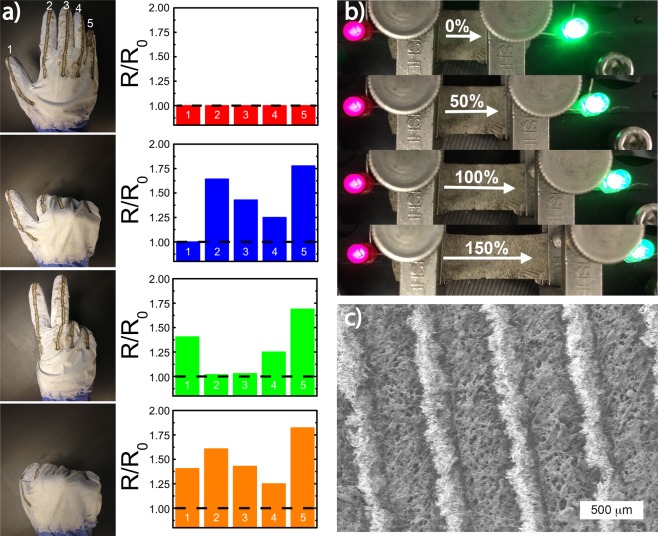

A proof of concept device utilizing this approach was demonstrated by depositing and patterning strain sensors. An elastomeric fiber mat was first solution blow spun directly on a nitrile glove (Figure 6a). A solution pen (Paasche F–I/32) with adjustable flow rate was then used to deposit a line of precursor solution (25% (wt/vol)) along each finger. The patterned lines were then nucleated into silver nanoparticles, thereby forming stretchable conductive lines corresponding to each finger. Resistance of each conductive line was measured while performing multiple hand gestures, where normalized resistance values corresponded to individual finger movements (Figure 6a). Glove strain sensors have also been shown previously using other materials.23,46 The strain dependence of electrical properties was evaluated separately to identify the difference between patterned stretchable conductors and bulk stretchable conductors (Figure S6, Supporting Information). This revealed that electrical properties resulting from localized nanoparticle nucleation have higher strain dependence as compared to bulk stretchable conductors, allowing for utilization as a strain sensor for relatively low strain conditions (ε < 50%).

Figure 6.

(a) Images of hand gestures performed wearing a nitrile glove coated with elastomeric fiber mat and patterned with conductive lines. Normalized resistance values for conductive lines patterned on each finger numbered from 1 to 5. (b) Images of LED circuit operating under various strain conditions (c) SEM image of parallel conductive lines patterned using spray coating.

A basic circuit consisting of 2 LEDs connected with a stretchable conductor prepared using 25% (wt/vol) STFA solution was also constructed (Figure 6b). The illumination of both LEDs remained stable while the conductive composite was stretched up to 150% strain (Figure 6b). Patternability and processability on planar substrates was demonstrated with spray techniques. A planar substrate with minimal surface roughness, such as a silicon wafer, allows for the use of a shadow mask. Utilizing this approach, a stretchable fiber mat on top of a silicon wafer was patterned with conductive parallel lines by applying precursor solution (25% (wt/vol) STFA) with a bottom feed airbrush through a shadow mask. Silver nanoparticles were then nucleated to form defined lines with a thickness of 300 μm and a conductivity of 1300 S/cm (Figure 6c).

Conclusions

We have developed a method to deposit conformal stretchable conductive fiber mats using solution blow spinning and metallic nanoparticle nucleation on nonplanar substrates. The stretchable fiber mats were able to combine electrical conductivity values as high as 2000 S/cm with R/R0 values as low as 1.12 after 400 cycles of 150% strain. The stable electrical properties of these stretchable conductors potentially stem from conductive pathways maintained through silver nanoparticle stabilized fiber-to-fiber contacts and strain induced structural changes. Additionally, the strain dependence of the electrical properties was tuned via localized nanoparticle nucleation or reduction in precursor concentration. Control of electromechanical properties allows for materials to be tailored for specific applications. To demonstrate the utility of this method we employed stretchable conductors in simple devices including strain sensors on nitrile gloves and stretchable electrodes connecting LEDs.

Methods

Stretchable Conductor Fabrication

Solutions of poly(styrene-block-isoprene-block-styrene) (SIS) (Sigma-Aldrich, 22 wt % styrene content) and tetrahydrofuran (THF) (Fisher Scientific, 99.9%) were prepared and fed with a constant feed rate (10 mL/h) through the nozzle of the solution blow spinning setup constructed from a transfer pipet and a flat tipped 18G needle connected to a syringe pump and compressed air line (Figure 1b). The air pressure was kept constant during the blow spinning process at 50 psi. Elastomeric fibers were accumulated on a metal mesh. The resulting polymer fiber construct was lifted from the metal mesh and immersed in a previously prepared organometallic solution consisting of silver trifluoroacetate (STFA) (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%) and ethanol (Pharmco-Aaper, 99%) for 30 min, then dried in a vacuum desiccator. Silver nanoparticle nucleation was initiated via dropwise addition of reducing solution consisting of hydrazine hydrate (50% (v/v)) (Sigma-Aldrich, 50%–60%), deionized water (25% (v/v)) and ethanol (25% (v/v)). The resultant conductive fiber composite was washed thoroughly with water to eliminate any unbound nanoparticles and dried overnight under vacuum.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Hitachi SU-70) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) (JEOL 2100F) were used to characterize the microstructure of the block copolymer nanoparticle composites. The TEM sample used for cross-section analysis was prepared using a microtome (Leica EM UC-6). Fiber diameter is reported as an average of 50 measurements taken from three SEM images. Nanoparticle diameter is reported as an average of 150 measurements taken from three TEM images. A dynamic mechanical analyzer (TA Instruments Q800) and an Instron tensile tester (model 3345) were used to characterize the mechanical properties of the stretchable conductors. Energy dissipation was calculated from the area of the hysteresis loops of cyclic stress/strain curves for both SIS fiber mats and conductive composites (n = 3, error bars represent standard deviation). The electrical conductivity of the stretchable conductor samples were measured using a custom built automated 4-point probe measurement system connected to a Keithey 2400 Sourcemeter (n=5, error bars represent standard deviation). The normalized resistance measurements under mechanical strain were performed using a high precision optical stage and an Ohmmeter (Amprobe 33XR-A).

Device Fabrication and Patterning

Strain sensors were fabricated via fiber mat deposition on a nitrile glove and subsequent nanoparticle nucleation. Once the glove was completely covered with elastomeric fibers, lines were drawn on each finger using a flow-pen (Paasche F-I/32) filled with STFA solution (25% (wt/vol)). The conductive lines were formed after hydrazine hydrate solution was applied dropwise onto the STFA patterned lines. The strain sensing measurements were performed using an Ohmmeter (Amprobe 33XR-A) attached to the conductive lines on the glove with alligator clips. The conductive composite connecting the LEDs was stretched using a precision optical stage, while being powered with a DC source (Hewlett-Packard E3630A) with constant voltage (5 V). The parallel lines were patterned on planar elastomeric fiber mats by spray coating 25% (wt/vol) STFA solution with a bottom feed airbrush (40 psi air pressure, 20 mL/h solution feed) through a micromachined shadow mask and subsequently nucleated by spray coating hydrazine hydrate solution. The patterned stretchable conductor was washed with water and dried under vacuum overnight prior to characterization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AFOSR Grant No. FA95500910430 and AFOSR/AOARD Grant No. FA23861414086. A.M.B. was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. F31EB019289. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Howard Wang for his input and help with characterization of electrical properties. We acknowledge the support from the Nanoscale Imaging, Spectroscopy, and Properties Laboratory (NISPLab) at the University of Maryland Nanocenter.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author Contributions

§ These authors contributed equally to this work

Supporting Information Available

Additional material including nanoparticle size distribution, mechanical testing, and electrical properties testing. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Sekitani T.; Nakajima H.; Maeda H.; Fukushima T.; Aida T.; Hata K.; Someya T. Stretchable Active-Matrix Organic Light-Emitting Diode Display Using Printable Elastic Conductors. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipomi D. J.; Tee B. C. K.; Vosgueritchian M.; Bao Z. N. Stretchable Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 1771–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khang D. Y.; Jiang H. Q.; Huang Y.; Rogers J. A. A Stretchable Form of Single-Crystal Silicon for High-Performance Electronics on Rubber Substrates. Science 2006, 311, 208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M.; Li X. F.; Kim C.; Hashimoto M.; Wiley B. J.; Ham D.; Whitesides G. M. Stretchable Microfluidic Radiofrequency Antennas. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2749–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T.; Hayamizu Y.; Yamamoto Y.; Yomogida Y.; Izadi-Najafabadi A.; Futaba D. N.; Hata K. A Stretchable Carbon Nanotube Strain Sensor for Human-Motion Detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipomi D. J.; Vosgueritchian M.; Tee B. C. K.; Hellstrom S. L.; Lee J. A.; Fox C. H.; Bao Z. N. Skin-Like Pressure and Strain Sensors Based on Transparent Elastic Films of Carbon Nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 788–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S.; Kim J. H.; Kim J.; Choi S.; Lee J.; Park I.; Hyeon T.; Kim D. H. Reverse-Micelle-Induced Porous Pressure-Sensitive Rubber for Wearable Human-Machine Interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 4825–4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son D.; Lee J.; Qiao S.; Ghaffari R.; Kim J.; Lee J. E.; Song C.; Kim S. J.; Lee D. J.; Jun S. W.; et al. Multifunctional Wearable Devices for Diagnosis and Therapy of Movement Disorders. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J. A.; Yeo W. H.; Su Y. W.; Hattori Y.; Lee W.; Jung S. Y.; Zhang Y. H.; Liu Z. J.; Cheng H. Y.; Falgout L.; et al. Fractal Design Concepts for Stretchable Electronics. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafabadi A. H.; Tamayol A.; Annabi N.; Ochoa M.; Mostafalu P.; Akbari M.; Nikkhah M.; Rahimi R.; Dokmeci M. R.; Sonkusale S.; et al. Biodegradable Nanofibrous Polymeric Substrates for Generating Elastic and Flexible Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5823–5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H.; Lu N. S.; Ma R.; Kim Y. S.; Kim R. H.; Wang S. D.; Wu J.; Won S. M.; Tao H.; Islam A.; et al. Epidermal Electronics. Science 2011, 333, 838–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.; Zhang Y. H.; Jia L.; Mathewson K. E.; Jang K. I.; Kim J.; Fu H. R.; Huang X.; Chava P.; Wang R. H.; et al. Soft Microfluidic Assemblies of Sensors, Circuits, and Radios for the Skin. Science 2014, 344, 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdeviren C.; Su Y. W.; Joe P.; Yona R.; Liu Y. H.; Kim Y. S.; Huang Y. A.; Damadoran A. R.; Xia J.; Martin L. W.; et al. Conformable Amplified Lead Zirconate Titanate Sensors with Enhanced Piezoelectric Response for Cutaneous Pressure Monitoring. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekitani T.; Someya T. Stretchable, Large-Area Organic Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2228–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekitani T.; Noguchi Y.; Hata K.; Fukushima T.; Aida T.; Someya T. A Rubberlike Stretchable Active Matrix Using Elastic Conductors. Science 2008, 321, 1468–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. H.; Vural M.; Islam M. F. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Aerogel-Based Elastic Conductors. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 2865–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F.; Zhu Y. Highly Conductive and Stretchable Silver Nanowire Conductors. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 5117–5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Gong S.; Chen Y.; Yap L. W.; Cheng W. L. Manufacturable Conducting Rubber Ambers and Stretchable Conductors from Copper Nanowire Aerogel Monoliths. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5707–5714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.; Zhu J.; Yeom B.; Di Prima M.; Su X. L.; Kim J. G.; Yoo S. J.; Uher C.; Kotov N. A. Stretchable Nanoparticle Conductors with Self-Organized Conductive Pathways. Nature 2013, 500, 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M.; Im J.; Shin M.; Min Y.; Park J.; Cho H.; Park S.; Shim M. B.; Jeon S.; Chung D. Y.; et al. Highly Stretchable Electric Circuits from a Composite Material of Silver Nanoparticles and Elastomeric Fibres. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Wang S. D.; Li M.; Ahn C.; Hyun J. K.; Kim D. S.; Kim D. K.; Rogers J. A.; Huang Y. G.; Jeon S. Three-Dimensional Nanonetworks for Giant Stretchability in Dielectrics and Conductors. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S.; So J. H.; Mays R.; Desai S.; Barnes W. R.; Pourdeyhimi B.; Dickey M. D. Ultrastretchable Fibers with Metallic Conductivity Using a Liquid Metal Alloy Core. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 2308–2314. [Google Scholar]

- Muth J. T.; Vogt D. M.; Truby R. L.; Menguc Y.; Kolesky D. B.; Wood R. J.; Lewis J. A. Embedded 3d Printing of Strain Sensors within Highly Stretchable Elastomers. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden N.; Brittain S.; Evans A. G.; Hutchinson J. W.; Whitesides G. M. Spontaneous Formation of Ordered Structures in Thin Films of Metals Supported on an Elastomeric Polymer. Nature 1998, 393, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.; Lee J.; Lee H.; Yeo J.; Hong S.; Nam K. H.; Lee D.; Lee S. S.; Ko S. H. Highly Stretchable and Highly Conductive Metal Electrode by Very Long Metal Nanowire Percolation Network. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3326–3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R. S.; Yu Y.; Xie Z.; Liu X. Q.; Zhou X. C.; Gao Y. F.; Liu Z. L.; Zhou F.; Yang Y.; Zheng Z. J. Matrix-Assisted Catalytic Printing for the Fabrication of Multiscale, Flexible, Foldable, and Stretchable Metal Conductors. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 3343–3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun K. Y.; Oh Y.; Rho J.; Ahn J. H.; Kim Y. J.; Choi H. R.; Baik S. Highly Conductive, Printable and Stretchable Composite Films of Carbon Nanotubes and Silver. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. B.; Pasta M.; La Mantia F.; Cui L. F.; Jeong S.; Deshazer H. D.; Choi J. W.; Han S. M.; Cui Y. Stretchable, Porous, and Conductive Energy Textiles. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko H. C.; Stoykovich M. P.; Song J. Z.; Malyarchuk V.; Choi W. M.; Yu C. J.; Geddes J. B.; Xiao J. L.; Wang S. D.; Huang Y. G.; et al. A Hemispherical Electronic Eye Camera Based on Compressible Silicon Optoelectronics. Nature 2008, 454, 748–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H.; Kim Y. S.; Wu J.; Liu Z. J.; Song J. Z.; Kim H. S.; Huang Y. G. Y.; Hwang K. C.; Rogers J. A. Ultrathin Silicon Circuits with Strain-Isolation Layers and Mesh Layouts for High-Performance Electronics on Fabric, Vinyl, Leather, and Paper. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3703–3707. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H.; Xiao J. L.; Song J. Z.; Huang Y. G.; Rogers J. A. Stretchable, Curvilinear Electronics Based on Inorganic Materials. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2108–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbrunner M.; Sekitani T.; Reeder J.; Yokota T.; Kuribara K.; Tokuhara T.; Drack M.; Schwodiauer R.; Graz I.; Bauer-Gogonea S.; et al. An Ultra-Lightweight Design for Imperceptible Plastic Electronics. Nature 2013, 499, 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn B. Y.; Duoss E. B.; Motala M. J.; Guo X. Y.; Park S. I.; Xiong Y. J.; Yoon J.; Nuzzo R. G.; Rogers J. A.; Lewis J. A. Omnidirectional Printing of Flexible, Stretchable, and Spanning Silver Microelectrodes. Science 2009, 323, 1590–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. T.; Pyo J.; Rho J.; Ahn J. H.; Je J. H.; Margaritondo G. Three-Dimensional Writing of Highly Stretchable Organic Nanowires. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S.; Lee J.; Song H.; Kim S.; Jeong J.; Hong Y.. Inkjet-Printed Stretchable Silver Electrode on Wave Structured Elastomeric Substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T.; Takei K.; Gillies A. G.; Fearing R. S.; Javey A. Carbon Nanotube Active-Matrix Backplanes for Conformal Electronics and Sensors. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5408–5413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore G. A.; Munzenrieder N.; Kinkeldei T.; Petti L.; Zysset C.; Strebel I.; Buthe L.; Troster G.. Wafer-Scale Design of Lightweight and Transparent Electronics That Wraps around Hairs. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros E. S.; Glenn G. M.; Klamczynski A. P.; Orts W. J.; Mattoso L. H. C. Solution Blow Spinning: A New Method to Produce Micro- and Nanofibers from Polymer Solutions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 2322–2330. [Google Scholar]

- Tutak W.; Sarkar S.; Lin-Gibson S.; Farooque T. M.; Jyotsnendu G.; Wang D. B.; Kohn J.; Bolikal D.; Simon C. G. The Support of Bone Marrow Stromal Cell Differentiation by Airbrushed Nanofiber Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2389–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A. M.; Casey B. J.; Sikorski M. J.; Wu K. L.; Tutak W.; Sandler A. D.; Kofinas P. In Situ Deposition of Plga Nanofibers Via Solution Blow Spinning. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S.; Chhatre S. S.; Mabry J. M.; Cohen R. E.; McKinley G. H. Solution Spraying of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Blends to Fabricate Microtextured, Superoleophobic Surfaces. Polymer 2011, 52, 3209–3218. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova-Damyanova B. Retention of Lipids in Silver Ion High-Performance Liquid Chromatography: Facts and Assumptions. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 1815–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon G. D.; Lim G. H.; Song J. H.; Shin M.; Yu T.; Lim B.; Jeong U. Highly Stretchable Patterned Gold Electrodes Made of Au Nanosheets. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2707–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. H.; Kim H. Y.; Ryu Y. J.; Kim K. W.; Choi S. W. Mechanical Behavior of Electrospun Fiber Mats of Poly(Vinyl Chloride)/Polyurethane Polyblends. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Phys. 2003, 41, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.; Lee B.; Kim C.; Kim H.; Kim K.; Nah C. Stress-Strain Behavior of the Electrospun Thermoplastic Polyurethane Elastomer Fiber Mats. Macromol. Res. 2005, 13, 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Amjadi M.; Pichitpajongkit A.; Lee S.; Ryu S.; Park I. Highly Stretchable and Sensitive Strain Sensor Based on Silver Nanowire-Elastomer Nanocomposite. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5154–5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmaier J. M.; Meyer G. C. Adhesive Properties of Aba Poly(Styrene-B-Isoprene)Block Copolymers. Polymer 1977, 18, 587–590. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. J.; Kim H. J.; Yoon G. H. Effect of Substrate and Tackifier on Peel Strength of Sis (Styrene-Isoprene-Styrene)-Based Hmpsas. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2005, 25, 288–295. [Google Scholar]

- Creton C.; Hu G. J.; Deplace F.; Morgret L.; Shull K. R. Large-Strain Mechanical Behavior of Model Block Copolymer Adhesives. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 7605–7615. [Google Scholar]

- Fukatsu K. Mechanical-Properties of Poly(Ethylene-Terephthalate) Fibers Imparted Hydrophilicity with Aminolysis. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1992, 45, 2037–2042. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.