Abstract

Functionalized quantum dots (QDs) have been widely explored for multimodality bioimaging and proven to be versatile agents. Attaching positron-emitting radioisotopes onto QDs not only endows their positron emission tomography (PET) functionality, but also results in self-illuminating QDs, with no need for an external light source, by Cerenkov resonance energy transfer (CRET). Traditional chelation methods have been used to incorporate the radionuclide, but these methods are compromised by the potential for loss of radionuclide due to cleavage of the linker between particle and chelator, decomplexation of the metal, and possible altered pharmacokinetics of nanomaterials. Herein, we described a straightforward synthesis of intrinsically radioactive [64Cu]CuInS/ZnS QDs by directly incorporating 64Cu into CuInS/ZnS nanostructure with 64CuCl2 as synthesis precursor. The [64Cu]CuInS/ZnS QDs demonstrated excellent radiochemical stability with less than 3% free 64Cu detected even after exposure to serum containing EDTA (5 mM) for 24 h. PEGylation can be achieved in situ during synthesis, and the PEGylated radioactive QDs showed high tumor uptake (10.8% ID/g) in a U87MG mouse xenograft model. CRET efficiency was studied as a function of concentration and 64Cu radioactivity concentration. These [64Cu]CuInS/ZnS QDs were successfully applied as an efficient PET/self-illuminating luminescence in vivo imaging agents.

Keywords: quantum dots, CRET, CuInS/ZnS, PET imaging, dual-modality imaging

Fluorescence imaging is of particular interest for preclinical qualitative applications due to its high sensitivity, low-cost and short acquisition time.1,2 It has been utilized to provide intraoperational guidance with various fluorophore conjugated probes,3 but suffers from lack of quantitation, shallow depth of penetration, and tissue autofluorescence.4 Positron emission tomography (PET) is also a powerful biomedical imaging technique widely used for diagnostic application in clinical oncology owing to the availability of high sensitivity and quantitative accuracy.5,6

Cerenkov luminescence (CL) has attracted intense interests in both preclinical research and clinical applications7,8 by bridging PET with optical imaging. Since the CL light is referred as the emission generated at or near the point of radionuclide decay, there is no limitation by the penetration depth of excitation light.9,10 Unfortunately, unlike the characteristic spectral peak from fluorescence molecules, CL spectra is continuous and more intense at higher frequencies (UV/blue),10,11 which is not suitable for in vivo imaging due to the tissue adsorption. To overcome the limitations, radioisotopes have been combined with various nanomaterials (NMs) including quantum dots (QDs),9,12 gold NPs13−16 and rare-earth NPs,17 in order to construct the Cerenkov resonance energy transfer (CRET) systems, where the NMs can be excited by the UV/blue luminescence and emit a red-shifted emission, which has much greater depth penetration.

Among various NMs, QDs are of particular interest to be adapted for CRET systems12,18 due to their superior optical properties, including high quantum yield, large Stokes shifts, high photostability and tunable fluorescence emission.19,20 The radiolabeled QDs are typically constructed by incorporating radioisotopes using a conjugation strategy21−23 that requires linking an exogenous chelator, such as 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA) or 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) to coordinate certain radioisotopes. However, this methodology creates some concerns for in vivo diagnostic imaging. First, the physicochemical properties of the NMs might be changed when attached with the radiometal-chelator.24 Second, the radiometal-chelator moiety may dissociate from the surface of NMs either through dissociation of the ligand from the metal core or transchelation of the metal into biological fluids, which could cause a mismatch in location between radionuclides and NMs. Third, the conjugation is challenging when the original surface is not conjugation friendly. Therefore, we set out to develop reliable chelator-free intrinsically radioactive QDs (RQDs) for in vivo imaging application.

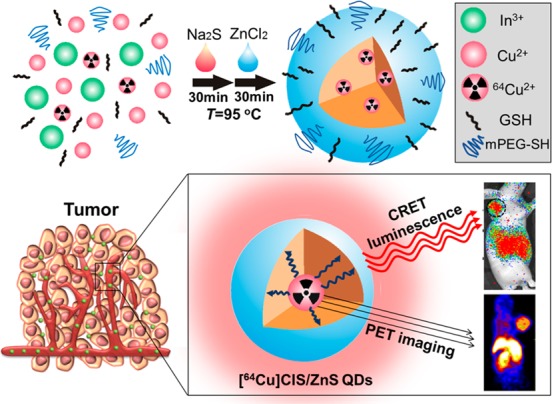

Recently, our group has doped 64Cu into CdSe/ZnS QDs via cation exchange reaction in organic phase and subsequently modified the surface with PEG.18 Compared with conventional Cd-containing QDs, CuInS/ZnS (CIS/ZnS) QDs have been developed as promising in vivo fluorescence nanoprobes due to low-toxicity and near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence.25,26 Herein, we reported a one-pot synthesis of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs for PET/self-illuminating NIR luminescence imaging, as shown in Scheme 1. These RQDs were prepared from metal chlorides, 64CuCl2, and sodium sulfide aqueous solutions and were in situ PEGylated with methoxy-PEG-thiol (mPEG-SH) as surface ligand. Since 64Cu atoms are introduced as integral building blocks of the aqueous CIS/ZnS QDs, the intrinsically incorporated 64Cu RQDs demonstrated high radiochemical stability. Even in the presence of EDTA (5 mM), less than 3% dissociated 64Cu was detected after the RQDs were challenged in serum for 24 h. The in situ PEGylation was realized during the RQD synthesis, which endowed the RQDs with excellent colloidal stability and biocompatibility. Compared with only glutathione (GSH) modified RQDs, the PEGylated RQDs had two times higher tumor uptake after intravenous injection into tumor xenografted mice. The QDs amount and 64Cu radioactivity level were varied to optimize the CRET efficiency and in vivo experimental results have proved that CRET was well maintained during circulation. We have demonstrated that our [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs have improved radioactive stability, optimized CRET luminescence, and successful utility for PET/CRET luminescence dual modal imaging of U87MG glioblastoma xenograft models.

Scheme 1. Illustration of the synthesis of intrinsically radioactive [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs for PET/CRET luminescence imaging.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis, Characterization, and Stability

This simple and straightforward method for making QDs was based on a previously reported synthetic strategy.27,28 Briefly, CIS/ZnS QDs were prepared in aqueous solution from CuCl2, InCl3, Na2S and subsequent shell formation by addition of ZnCl2 aqueous solutions and in situ capped with PEG and glutathione (GSH). The CIS/ZnS QDs had a PL excitation spectrum overlapping the UV/blue emissions of Cerenkov radiation and exhibited NIR fluorescence centered at 680 nm with quantum yields (QYs) up to 25% (see Supporting Information). These properties made these QDs favorable energy transfer agent for CRET. For the synthesis of radioactive QDs (illustrated in Scheme 1), trace amount of 64CuCl2 was added to the initial reaction solution and intrinsically incorporated into the nanostructure of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs upon the addition of Na2S. [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs exhibited similar fluorescent property with the nonradioactive QDs, as shown in Figure 1A. The in situ PEGylation for the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs was achieved during the synthesis with mPEG-SH and GSH as surface ligands. As shown in Figure 1B, GSH capped RQDs (GSH-RQDs) had a hydrodynamic diameter (HD) of 6.5 nm, whereas the PEGlyated RQDs showed a larger HD of 23 nm. After incubated in PBS with 10% human serum for 24 h, negligible change in HDs was observed for both GSH-RQDs and PEGylated RQDs, indicating that both samples have good colloidal stability.

Figure 1.

(A) The photoluminescence (PL) emission spectra (λex = 470 nm). (B) Hydrodynamic diameter distribution of GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS (blue) and PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs (red) in PBS buffer. (C) The hydrodynamic diameters temporal evolution of the CIS/ZnS QDs incubated in PBS with 10% human serum at 37 °C. (D) The radio instant thin-layer chromatography analyses of the 64CuCl2 and resulted raw [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs aqueous solution immediately after preparation. (E) Radiochemical stability of the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs incubated in various media at 37 °C for 1, 4, and 24 h. The PL and HDs measurements for [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs were conducted after 1 week decay.

The radiochemical purity of the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs following synthesis was confirmed by the instant thin-layer chromatography (ITLC) as shown in Figure 1D. The ITLC method resulted in retention of the QDs at the origin of the plate, while unincorporated 64Cu migrated with the solvent front. It is shown that all the radioactivity of the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs was associated with 64Cu atoms integrated in their nanocrystals without any contribution from the unincorporated free 64Cu, indicating a nearly 100% labeling yield. The radiochemical stability of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs was evaluated in various media, including phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), PBS with a challenging agent of EDTA (5 mM), mouse serum, and mouse serum with EDTA (5 mM), by incubating the QDs at 37 °C. As shown in Figure 1E and (see Supporting Information), the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs showed no release of free 64Cu in PBS and serum for up to 24 h. Furthermore, even under constant challenge of 5 mM EDTA, less than 3% free 64Cu dissociation from the RQDs was detected at 24 h postincubation, which indicates better radiochemical stability of our [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs than 64Cu-DOTA in serum.22,29

In Vitro CRET Investigation

The luminescence images were obtained on an IVIS Lumina optical imaging system with various band-pass filters. As shown in Figure 2A, the 64CuCl2 solution showed a continuous luminescence spectra which was more intense in the UV/blue region, while the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs presented a spectrum with a broad maximum at the red region (600–750 nm) that corresponded to their PL emission spectrum (Figure 1). Quantitative analysis (see Figure S3 in Supporting Information) showed that the total photon flux of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs was almost 4 times that of pure 64CuCl2 solution. We also observed that for [64Cu]RQD, the proportion of photon flux above the 590 nm cut off was 85% of the total photon flux while only 34% for 64CuCl2 solution. All these results indicate that RQDs have successfully converted the UV photons from Cerenkov radiance, most of which is out of the detectable range of IVIS system into red-shifted photons that can be acquired by qthe system.

Figure 2.

(A) The plots of photon flux obtained with different narrow filters. (B) PET, photoluminescence (PL) and CRET luminescence images derived with various narrow filters for the 64CuCl2 (a, 150 μCi), [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs (b, 150 μCi, 25 μg) ,and CIS/ZnS nonradioactive QDs (c, 25 μg) aqueous solutions, respectively. The CRET luminescence images were acquired with acquisition time of 4 min. The PL images were obtained under blue excitation light with exposure time of 0.1 s.

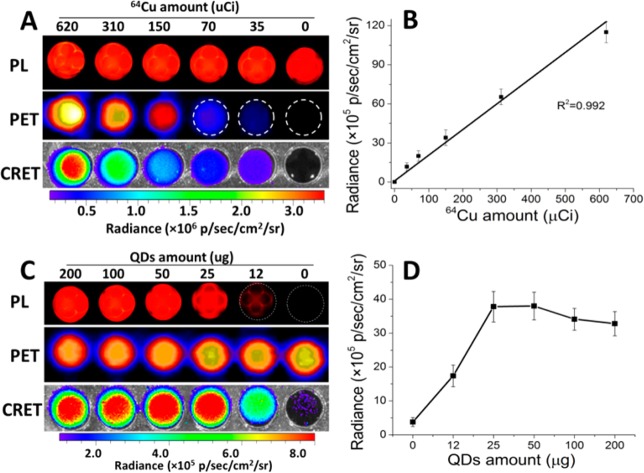

The nearly 100% product yield is favorable for a systematic study of the influence of RQDs amount and 64Cu radioactivity on CRET luminescence. Some 200 μL aqueous suspensions of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs (50 μg) with various amount of 64Cu radioactivity (Figure 3A) and different amount of QDs with 150 μCi of 64Cu (Figure 3C) were placed in a 96-well black plate and imaged for in vitro phantom study. As shown in Figure 3B, the total photon flux in the red filtered images (>590 nm) was linearly correlated to the radioactivity of 64Cu with fixed amount of QDs (50 μg). When the radioactivity was fixed at 150 μCi, the photon flux increased with increasing amount of host QDs up to 25 μg. However, the signal intensity reached a plateau and even slightly decreased with more than 25 μg of QDs. This is probably due to “concentration quenching”,30 which happens when the concentration of QDs is too high while the excitation intensity is kept constant.31 From Figure 3D, we can see that the CRET efficiency reached maximum at a 64Cu radioactivity to QDs amount ratio of 6. Thus, we used 50 μg of RQDs (300 μCi) for in vivo experiment with their optimal CRET efficiency.

Figure 3.

Optical and PET images of aqueous suspension of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs with different amount of radioactivity and QDs in a 96-well plate. (A) Amount of RQDs kept constant (50 μg); (C) amount of radioactivity (150 μCi) kept constant. (B) Corresponding plot of photon flux vs radioactivity; (D) corresponding plot of photon flux vs QD concentration. The CRET luminescence images were acquired with a red filter (>590 nm).

In Vivo Imaging and Biodistribution

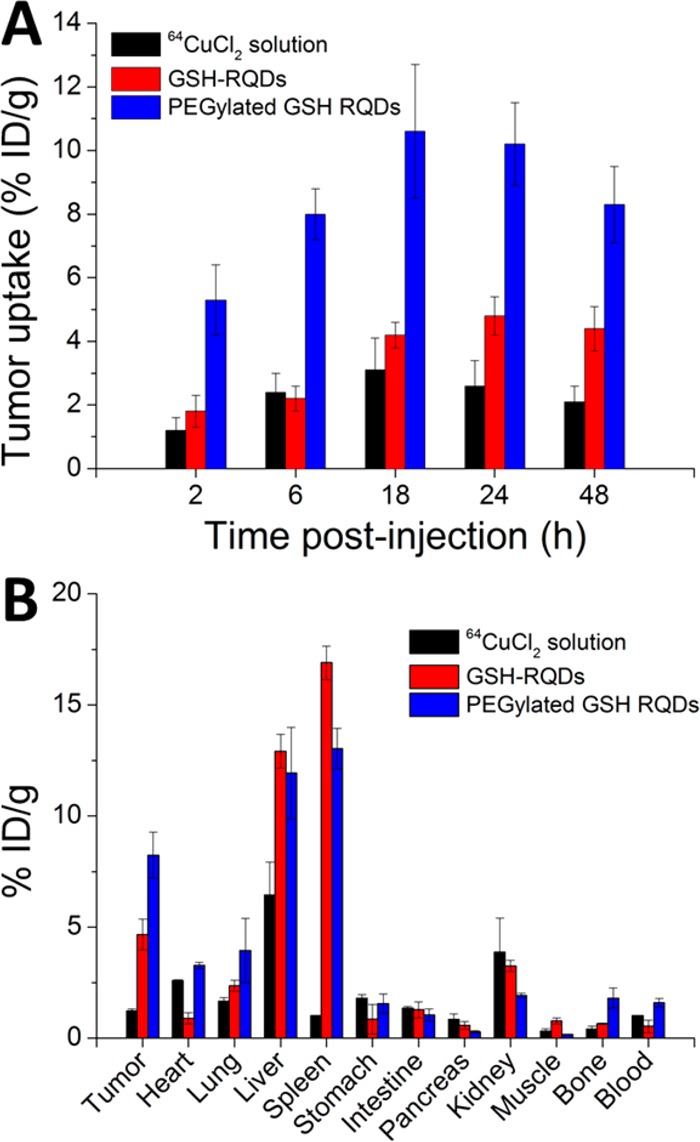

Prior to further in vivo experiments, cytotoxicity of obtained PEGylated and GSH–CIS/ZnS QDs was tested on U87MG cells. No apparent loss of cell viability was observed even after incubation with CIS/ZnS QDs at a concentration of 100 μg/mL for 24 h (Figure S4, see Supporting Information). We next explored the in vivo biodistribution of the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs in mice bearing U87MG tumors. We first quantitatively compared the tumor uptake of GSH-RQDs, PEGylated GSH-RQDs and free 64Cu via PET imaging. In the whole-body PET images of mice, the major organs (liver, spleen and tumor) were all clearly visualized (Figure 4). The quantitative region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of the whole-body PET images proved that the PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs showed the highest tumor uptake (10.8% ID/g at 18 h), compared with GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs (4.4% ID/g at 18 h) and 64CuCl2 solution (3.2% ID/g at 18 h). The higher tumor targeting efficiency of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs over free 64Cu is due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.32 PEGylation is expected to enhance the circulation of nanoparticles and thus improved the tumor accumulation.33 We also observed that GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs showed a high bladder uptake during 2 to 24 h while PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs showed only negligible signal in the bladder, which was consistent with the previous report that nanoparticles smaller than the kidney filtration threshold of 5.5 nm can be easily excreted by renal clearance.34 Tumor uptake of PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs was 7.8% ID/g at 6 h postinjection; the uptake increased to 10.8 ± 1.3% ID/g at 18 h postinjection followed by a slow decrease to 8.3% ID/g at 48 h postinjection. Biodistribution data obtained from dissection and γ counting were measured at 48 h postinjection (Figure 5) and were consistent with PET ROI analysis. It is worth mentioning that with the same injected dose of radioactivity, free 64Cu showed a much lower major organ uptake than GSH-RQDs and PEGylated GSH-RQDs due to the renal and intestinal clearance of 64CuCl2.35,36 Our result revealed the significant effect of the nanoparticle surface properties on their in vivo behavior.

Figure 4.

Representative whole-body coronal PET images of U87MG tumor-bearing mice at 2, 6, 18, 24, and 48 h after intravenous injection of 100 μL (50 μg, 300 μCi) of 64CuCl2, GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS and PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs (3 mice each group). Arrow indicates location of the tumor.

Figure 5.

(A) PET ROI analysis of U87MG tumor uptake of 64CuCl2, GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS and PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs over time (3 mice each group). (B) Biodistribution of 64CuCl2, GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS and PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs in mice bearing U87MG tumors at 48 h postinjection. (3 mice each group).

We also investigated the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs for in vivo fluorescence imaging. As shown in Figure S5 (see Supporting Information), the same mice used for PET imaging were immediately imaged under blue light excitation at various time points postinjection. The mice administrated with 64CuCl2 solution were not imaged by Maestro due to lack of fluorescence signal. Consistent with the PET imaging results, both GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs and PEGylated -[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs showed distinct tumor accumulation. However, the limited penetration of the external excitation light and the strong tissue autofluorescence hampered the imaging of the deeper tissues, such as liver, and caused high background emissions. Because of these issues, fluorescence imaging of the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs is less favorable compared to PET for a in vivo whole-body imaging.

As proof-of-principle, we further evaluated the feasibility of using the obtained [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs as CRET system for in vivo luminescence imaging. In this case, the same mice for the PET and fluorescence imaging study were also used for luminescence imaging on a conventional small-animal IVIS Lumina optical imaging system. We imaged the mice at 6 h postinjection with open (400–920 nm) and red (>590 nm) filter, respectively. As shown in Figure 6, the tumor showed prominent luminescence signal over the background in all the mice. With open filter, the photon flux of PEGylated RQDs was 1.5 times higher than that of GSH-RQDs and 3 times higher than that of 64CuCl2 solution (Figure 6B). Since GSH-RQDs and 64CuCl2 has similar tumor uptake at 6 h (Figure 5A), the luminescence enhancement in the presence of GSH-RQDs should be due to the fact that CL has been successfully red-shifted by RQDs via CRET even after circulation in living mice and is more suitable for in vivo imaging. This is further confirmed by the observation that the photon flux obtained via the red filter (Fred) was found to be around 75% of the total photon flux (Ftotal) for GSH-RQDs, while the percentage was only 25% for the 64CuCl2 solution (Figure 6C). For PEGylated GSH-RQDs, when sharing a similar Fred to Ftotal ratio with that of GSH-RQDs, the higher tumor uptake leads to an even higher luminescence signal. Therefore, our PEGylated RQDs could be used as CRET luminescence imaging for semiquantitative whole body imaging with higher tumor uptake and signal-to-background ratio.

Figure 6.

(A) CRET images of U87MG tumor-bearing mice at 6 h postinjection of 100 μL (300 μCi) of 64CuCl2, GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS and PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs, respectively. Circle, tumor area (3 mice each group). These luminescence images were acquired without excitation light with open and red filter (>590 nm). (B) Total photon flux in the corresponding tumor region obtained with open and red filter (*p < 0.05, n = 3). (C) The percentage of photon flux under red filter in the total photon flux.

In order to evaluate the potential toxicity of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs, we injected 50 μg (300 μCi) of PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs per animal into mice and collected major organs, including heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney at 2 and 14 days post injection. Tissues were sliced and H&E staining examinations were conducted. As shown in Figure 7, gross evaluation and histopathology suggested no organ abnormality or lesion in the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs administrated mice, indicating good biocompatibility of the obtained QDs, and thus suitable for animal experiments.

Figure 7.

H&E stained images of major organs collected from control and PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs administrated mice at 2 and 14 days postinjection after 64Cu decay. The dosage was 100 μL (50 μg, 300 μCi) of PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs PBS solution.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated a straightforward synthesis of intrinsically radiolabeled [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs and then examined their potential use as a new platform for PET/self-illuminating luminescence imaging. The direct incorporation of 64Cu into the nanostructure of QDs enabled improved radiochemical stability. Even when the intrinsically RQDs were exposed to extremely challenging conditions for 24 h, less than 3% detached free 64Cu was detected. Surface PEGylation, achieved in situ during the RQDs synthesis, significantly improved the biocompatibility and resulted in increased tumor uptake. Compared with GSH-RQDs, the PEGylated RQDs showed higher tumor uptake to a maximum of 10.8%ID/g. The Cerenkov luminescence of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs, which is optimized by controlling the QDs amount and 64Cu radioactivity level, was successfully applied for in vivo tumor imaging.. Taken together, these [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs prepared by this facile strategy can serve as a new platform for dual-modality imaging and will find much wider application in the cancer imaging.

Experimental Section

Materials

Copper(II) chloride (CuCl2·2H2O, 99.0%), indium chloride (InCl3, 99.9%), zinc chloride (ZnCl2, 99.9%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97%), sodium sulfide (Na2S·9H2O, 98%), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), l-glutathione (GSH, reduced) and mouse serum were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Methoxy-PEG-thiol (mPEG-SH; Mw = 5000 Da) was purchased from Nanocs (New York, NY). 64CuCl2 was produced by the PET Department, NIH. Deionized (DI) water with resistivity of 18.2 MΩ was from a Millipore Autopure system. Ethanol (99.7%) and PD-10 columns were purchased from General Electric. All the chemicals and solvents were at least ACS grade and were used without further purification.

Characterizations

The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired with a FEI Tecnai 12 (120 kV). The TEM samples were prepared by depositing the diluted aqueous dispersion of QDs onto the carbon-coated copper grids. The fluorescence emission and UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitach F-7000) and Genesys 10S UV–vis Spectrophotometer, respectively. The hydrodynamic diameters and zeta potentials of the QDs were tested by scientific nanoparticle analyzer (SZ-100, Horiba). For the in vitro CRET investigation, 200 μL of aqueous suspensions of different samples was placed in the 96-well black plate (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) in the light-tight chamber. All the luminescent images were acquired after 4 min scanning with various filters. The acquired images were analyzed by the Living Image 3.0 software (Caliper Life Science, Hopkinton, MA) and the signal was normalized to photons per second per centimeter square per steradian (p/s/cm2/sr).

Synthesis of in Situ PEGylated GSH–CIS/ZnS QDs

The synthesis was developed from the reported methods27,28 with some modifications. The preparation of all precursor stock solution is described in the Supporting Information. Typically, CuCl2 (0.5 mL, 0.02 M), InCl3 (100 μL, 0.4 M), GSH (0.9 mL 0.1 M) and 50 mg of mPEG-SH (0.01 mmol) were loaded into a 50 mL three-neck flask. The pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 8.0 using 500 μL of NaOH solution (1 M) and the total volume was brought to 20 mL by addition of DI water. Then, fresh Na2S solution (1 mL, 0.06 M) was quickly injected into the mixture under magnetic stirring. The reaction solution was heated to 95 °C and maintained at that temperature for 1 h. The color of the reaction solution progressively changed from colorless through yellowish, orange and finally deep red. After 1 h incubation, 1 mL of ZnCl2 solution was injected into the flask and the temperature was kept at 95 °C for another 30 min. Then the solution was cooled down to room temperature. The resulted aqueous CIS/ZnS QDs were precipitated by adding excess ethanol and centrifugation (10 000g) for 15 min. The precipitated QDs were redispersed into 200 μL of DI water and purified by PD-10 column.

Synthesis of Intrinsically Radiolabeled PEGylated GSH-[64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs

Twenty mL precursor solution containing CuCl2, InCl3, GSH and mPEG-SH was prepared as described above. One milliliter of the solution was transferred into an Eppendorf tube (1.5 mL size). Typically, 64CuCl2 (1 mCi, 10 μL) and 50 μL Na2S solution (0.06 M) were added sequentially at room temperature under magnetic stirring. Then, the resulting solution was incubated at 95 °C for 1 h. Next, 50 μL of ZnCl2 solution was added into the reaction solution and heating continued for 30 min. The solution was then cooled to room temperature. The radiolabeling efficiency of the RQDs was confirmed by instant thin-layer chromatography before using. Syntheses were also conducted at varying ratios of 64Cu to the stable elements in order to study the effects on CRET efficiency.

Radiochemical Stability of [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs

The radiochemical stabilities of the obtained RQDs were investigated by incubating purified [64Cu]CIS/ZnS QDs (50 μL) in PBS buffer (500 μL), PBS buffer with 5 mM EDTA (500 μL), mouse serum (500 μL) and mouse serum with 5 mM EDTA (500 μL) at 37 °C for up to 24 h. The radiolabeling efficiency and stability of the RQDs were analyzed by instant thin-layer chromatography (iTLC). Incubation solution (∼2 μL) was spotted at the origin. Free 64Cu migrated to the solvent front and the RQDs remained at the origin. TLC chromatograms were quantitatively analyzed using a BioScan AR2000. The TLC chromatography data were exported as text file and plotted in 3 pt width line by Origin Software.

In Vivo Imaging Experiments

All the experiments involving animals were carried out in accordance with a protocol approved by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center Animal Care and Use Committee (NIH CC/ACUC). Human U87 glioblastoma tumors were grown in the right shoulder of the nude mice (20–25 g, Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) by subcutaneously injecting 5 × 106 tumor cells suspended in 100 μL of PBS. When the tumors grew to 7–9 mm in diameter, the tumor bearing mice were intravenously injected with 100 μL of [64Cu]RQDs or 64CuCl2 solution (300 μCi) for PET scanning and optical imaging at different time points postinjection. The in vivo CRET luminescence imaging was performed with IVIS Lumina II XR System (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). The luminescent images (excitation filter was closed and emission filter was open) were acquired after 10 min scanning without and with red filter (>590 nm), respectively. The acquired images were analyzed by the Living Image 3.0 software (Caliper Life Science, Hopkinton, MA) and the signal was normalized to photons per second per centimeter square per steradian (p/s/cm2/sr). In vivo photoluminescence imaging was obtained with a Maestro In Vivo Spectrum Imaging System (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Woburn, MA), using blue light as the excitation. The PET scanning and imaging analysis were performed on an Inveon microPET scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions). The details of small animal PET imaging and regions of interest (ROIs) analysis were previously reported.37 For each PET scan, 3-dimensional ROIs were drawn over the tumor on decay-corrected whole-body coronal images. The average radioactivity concentration was calculated based on the mean pixel values within the ROI volume, which was then converted to counts per milliliter per minute via a predetermined conversion factor.37 Given that a tissue density is 1 g/mL, the counts per milliliter per minute were converted to counts per gram per minute, and the values were then divided by the injected dose to obtain the image ROI-derived percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g). For the biodistribution analysis, the mice were sacrificed at 48 h postinjection and the major organs of interest were collected, wet weighed, and the radioactivity was measured in a well gamma-counter (Wallach Wizard, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Standards of the injected dose were prepared and measured along with the samples to calculate percentage of the injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National High Technology Program of China (2012AA022603), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51373117 and 81171372), The Key Project of Tianjin Nature Science Foundation (13JCZDJC33200), Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20120032110027), and the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, W. Guo was funded in part by the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Supporting Information Available

This included UV–vis absorption, PL excitation spectrum, TEM, zeta potential of the PEGylated GSH-CIS/ZnS QDs, radio instant thin-layer chromatography profiles of the [64Cu]CIS/ZnS RQDs in various medias, MTT assay data and in vivo fluorescence imaging of RQDs, Cerenkov enhancement assay, and PL QYs determination. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Louie A. Multimodality Imaging probes: Design and Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3146–3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon J.; Lee J.-H. Synergistically Integrated Nanoparticles as Multimodal Probes for Nanobiotechnology. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1630–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q. T.; Tsien R. Y. Fluorescence-Guided Surgery with Live Molecular Navigation—A New Cutting Edge. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 653–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So M.-K.; Xu C.; Loening A. M.; Gambhir S. S.; Rao J. Self-Illuminating Quantum Dot Conjugates for in Vivo Imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Chen X. Multimodality Molecular Imaging of Tumor Angiogenesis. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 113S–128S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ametamey S. M.; Honer M.; Schubiger P. A. Molecular Imaging with PET. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1501–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucignani G. Čerenkov Radioactive Optical Imaging: A Promising New Strategy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2011, 38, 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorek D. L.; Robertson R.; Bacchus W. A.; Hahn J.; Rothberg J.; Beattie B. J.; Grimm J. Cerenkov Imaging—A New Modality for Molecular Imaging. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 2, 163–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dothager R. S.; Goiffon R. J.; Jackson E.; Harpstrite S.; Piwnica-Worms D. Cerenkov Radiation Energy Transfer (CRET) Imaging: A Novel Method for Optical Imaging of PET Isotopes in Biological Systems. PLoS One 2010, 5, e13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Liu H.; Cheng Z. Harnessing the Power of Radionuclides for Optical Imaging: Cerenkov Luminescence Imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 2009–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard Y.; Collin B.; Decréau R. A. Inter/Intramolecular Cherenkov Radiation Energy Transfer (CRET) from a Fluorophore with a Built-In Radionuclide. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6711–6713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Zhang X.; Xing B.; Han P.; Gambhir S. S.; Cheng Z. Radiation-Luminescence-Excited Quantum Dots for in Vivo Multiplexed Optical Imaging. Small 2010, 6, 1087–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Liu Y.; Luehmann H.; Xia X.; Wan D.; Cutler C.; Xia Y. Radioluminescent Gold Nanocages with Controlled Radioactivity for Real-Time in Vivo Imaging. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 581–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Hao G.; Thomas P.; Liu J.; Yu M.; Sun S.; Öz O. K.; Sun X.; Zheng J. Near-Infrared Emitting Radioactive Gold Nanoparticles with Molecular Pharmacokinetics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 124, 10265–10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Sultan D.; Detering L.; Cho S.; Sun G.; Pierce R.; Wooley K. L.; Liu Y. Copper-64-Alloyed Gold Nanoparticles for Cancer Imaging: Improved Radiolabel Stability and Diagnostic Accuracy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Huang X.; Yan X.; Wang Y.; Guo J.; Jacobson O.; Liu D.; Szajek L.; Zhu W.; Niu G.; Kiesewetter D. O.; Sun S.; Chen X. Chelator-Free 64Cu Integrated Au Nanomaterials for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Guided Photothermal Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8438–8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Kang F.; Xu F.; Feng A.; Zhao Y.; Lu T.; Yang W.; Wang Z.; Lin M.; Wang J. Enhancement of Cerenkov Luminescence Imaging by Dual Excitation of Er3+, Yb3+-Doped Rare-Earth Microparticles. PLoS One 2013, 8, e77926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Huang X.; Guo J.; Zhu W.; Ding Y.; Niu G.; Wang A.; Kiesewetter D. O.; Wang Z. L.; Sun S.; Chen X. Self-Illuminating 64Cu-Doped CdSe/ZnS Nanocrystals for In Vivo Tumor Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1706–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong K.-T. Quantum Dots for Biophotonics. Theranostics 2012, 2, 629–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalet X.; Pinaud F. F.; Bentolila L. A.; Tsay J. M.; Doose S.; Li J. J.; Sundaresan G.; Wu A. M.; Gambhir S. S.; Weiss S. Quantum Dots for Live Cells, in Vivo Imaging, and Diagnostics. Science 2005, 307, 538–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarko D.; Eisenhut M.; Haberkorn U.; Mier W. Bifunctional Chelators in the Design and Application of Radiopharmaceuticals for Oncological Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 2667–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadas T. J.; Wong E. H.; Weisman G. R.; Anderson C. J. Coordinating Radiometals of Copper, Gallium, Indium, Yttrium, and Zirconium for PET and SPECT Imaging of Disease. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2858–2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Welch M. J. Nanoparticles Labeled with Positron Emitting Nnuclides: Advantages, Methods, and Applications. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23, 671–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen J. T.; Persson M.; Madsen J.; Kjær A. High Tumor Uptake of 64Cu: Implications for Molecular Imaging of Tumor Characteristics with Copper-Based PET Tracers. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2013, 40, 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W.; Chen N.; Tu Y.; Dong C.; Zhang B.; Hu C.; Chang J. Synthesis of Zn-Cu-In-S/ZnS Core/Shell Quantum Dots with Inhibited Blue-Shift Photoluminescence and Applications for Tumor Targeted Bioimaging. Theranostics 2013, 3, 99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie R.; Rutherford M.; Peng X. Formation of High-Quality I-III-VI Semiconductor Nanocrystals by Tuning Relative Reactivity of Cationic Precursors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5691–5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Li S.; Huang L.; Pan D. Green and Facile Synthesis of Water-Soluble Cu-In-S/ZnS Core/Shell Quantum Dots. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 7819–7821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Li S.; Huang L.; Pan D. Low-Cost and Gram-Scale Synthesis of Water-Soluble Cu-In-S/ZnS Core/Shell Quantum Dots in an Electric Pressure Cooker. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 1295–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Liu Y.; Luehmann H.; Xia X.; Brown P.; Jarreau C.; Welch M.; Xia Y. Evaluating the Pharmacokinetics and in Vivo Cancer Targeting Capability of Au Nanocages by Positron Emission Tomography Imaging. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5880–5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel S.; Podkorytova A.; Rempel A. Concentration Quenching of Fluorescence of Colloid Quantum Dots of Cadmium Sulfide. Phys. Solid State 2014, 56, 568–571. [Google Scholar]

- Willard D. M.; Carillo L. L.; Jung J.; Van Orden A. CdSe-ZnS Quantum Dots as Resonance Energy Transfer Donors in a Model Protein-Protein Binding Assay. Nano Lett. 2001, 1, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Cui Y.; Levenson R. M.; Chung L. W.; Nie S. In Vivo Cancer Targeting and Imaging with Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Yu M.; Ning X.; Zhou C.; Yang S.; Zheng J. PEGylation and Zwitterionization: Pros and Cons in the Renal Clearance and Tumor Targeting of Near-IR-Emitting Gold Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 125, 12804–12808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. S.; Liu W.; Misra P.; Tanaka E.; Zimmer J. P.; Ipe B. I.; Bawendi M. G.; Frangioni J. V. Renal Clearance of Quantum Dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1165–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng F.; Lu X.; Janisse J.; Muzik O.; Shields A. F. PET of Human Prostate Cancer Xenografts in Mice with Increased Uptake of 64CuCl2. J. Nucl. Med. 2006, 47, 1649–1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura S.; Nozaki S.; Hamazaki T.; Takeda T.; Ninomiya E.; Kudo S.; Hayashinaka E.; Wada Y.; Hiroki T.; Fujisawa C. PET Imaging Analysis with 64Cu in Disulfiram Treatment for Aberrant Copper Biodistribution in Menkes Disease Mouse Model. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson O.; Weiss I. D.; Szajek L. P.; Niu G.; Ma Y.; Kiesewetter D. O.; Farber J. M.; Chen X. PET Imaging of CXCR4 Using Copper-64 Labeled Peptide Antagonist. Theranostics 2011, 1, 251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.