Abstract

A variety of genetic backgrounds cause the loss of function of thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter, encoded by SLC12A3, responsible for the phenotypes in Gitelman syndrome. Recently, the phenomenon of exon skipping, in which exonic mutations result in abnormal splicing, has been associated with various diseases. Specifically, mutations in exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) sequences can promote exon skipping. Here, we used a bioinformatics program to analyze 88 missense mutations in the SLC12A3 gene and identify candidate mutations that may induce exon skipping. The three candidate mutations that reduced ESE scores the most were further investigated by minigene assay, and two (p.A356V and p.M672I) caused abnormal splicing in vitro. Furthermore, we identified the p.M672I (c.2016G>A) mutation in a patient with Gitelman syndrome and found that this single nucleotide mutation causes exclusion of exon 16 in the SLC12A3 mRNA transcript. Functional analyses revealed that the protein encoded by the aberrant SLC12A3 transcript does not transport sodium. These results suggest that aberrant exon skipping is one previously unrecognized mechanism by which missense mutations in SLC12A3 can lead to Gitelman syndrome.

Keywords: Gitelman‘s syndrome, genetic renal disease, hypokalemia

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is an autosomal recessive renal tubular disease characterized by hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalciuria.1 The clinical symptoms of GS are the result of a malfunctioning of the SLC12A3 gene, which encodes the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) in the distal convoluted tubules of the nephron.1 To date, >160 mutations, including missense, nonsense, frameshift, and splice-site mutations, as well as gene rearrangements, have been documented in GS.2 Among them, only a small number of missense mutations have been reported as exhibiting reduced function or as being nonfunctional.3–6 Because the precise molecular basis of the residual missense mutations in GS remains unknown, novel approaches to clarify these issues are urgently needed.

In general, exonic point mutations are categorized into missense, silent, or nonsense mutations, and it is well known that point mutations that damage the authentic splice sites cause abnormal splicing. However, it was recently reported that certain point mutations regarded as missense alterations also induce the exclusion of an individual exon in various diseases.7 The distinctive mechanism of “exon skipping” is closely linked to the disruption of the regulatory elements in genomic DNA.

The correct recognition of the splice sites is precisely controlled. The inclusion of exons in mature mRNA depends on intrinsic regulatory sequences. Among these sequences, exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), which are located at varying distances from the splice sites, help regulate normal splicing.7 The ESEs bind the serine/arginine-rich splicing factors (SRSFs) that enhance the recognition of the splice sites. Mutations within the ESEs exert an inhibitory effect on the binding of SRSFs following a failure of correct splicing due to exon skipping in mature mRNA.8–10 This “exon skipping due to ESE disruption” has been well-investigated in certain neurologic and inherited pediatric disorders.11,12 A novel therapeutic approach that normalizes aberrant splicing by the administration of specific reagents have already been applied to animal models.13–16

Therefore, we aimed to account for the loss-of-function mechanism of missense mutations in GS by the concept of exon skipping. As a result, we found that an exonic mutation formerly categorized as a missense alteration indeed causes abnormal splicing in the SLC12A3 transcript, resulting in non-functional cotransporter in GS.

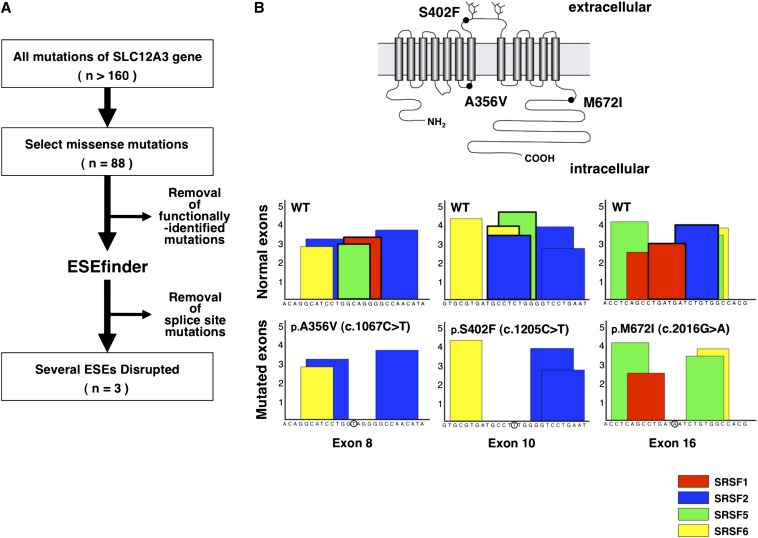

Among the >160 mutations reported in GS, we selected 88 missense mutations that were previously reported or are accessible from the PubMed database (Supplemental Table1). The mutations screened through the flow diagram (Figure 1A) were analyzed with a bioinformatics program to evaluate whether the mutations affected the ESE score matrices. Three of the most likely candidates (p.A356V, p.S402F, and p.M672I) were selected (Figure 1B). The p.A356V and p.S402F mutations were previously reported.17,18 In contrast, the p.M672I mutation was a novel variation found in a Japanese patient with GS. The p.A356V (c.1067C>T in exon8) mutation exhibited a decrease in the SRSF1 and SRSF5 scores to below the threshold level (Figure 1B). The p.S402F (c.1205C>T in exon10) mutation had a decrease in the SRSF2, SRSF5, and SRSF6 scores, and the p.M672I (c.2016G>A in exon16) mutation had a decrease in the SRSF1 and SRSF2 scores. These data suggest that these mutations may disrupt the ESE sequences following exon skipping.

Figure 1.

In silico prediction of exotic splicing among non-functional mutations in SLC12A3. (A) Candidates for potential exon skipping were screened with a bioinformatics program. Previously reported but not yet functionally identified missense mutations were investigated in this study. The splice site mutations are those missense mutations predicted to affect the 5′ donor or 3′ acceptor area of splice sites. (B) Predicted topology of the human NCC; the most likely candidates for exon skipping are illustrated. The NCC is a glycoprotein consisting of 12 transmembrane domains with 2 N-glycosylation sites and the long amino and carboxyl terminal domains. The positions of three candidates are shown in solid circles (upper panel). The potential ESE sequences were identified by ESEfinder software. The boxes are illustrated in red for SRSF1, blue for SRSF2, green for SRSF5, and yellow for SRSF6. The Y-axis indicates the numerical score identical with the consensus motifs of each SRSF (lower panel).

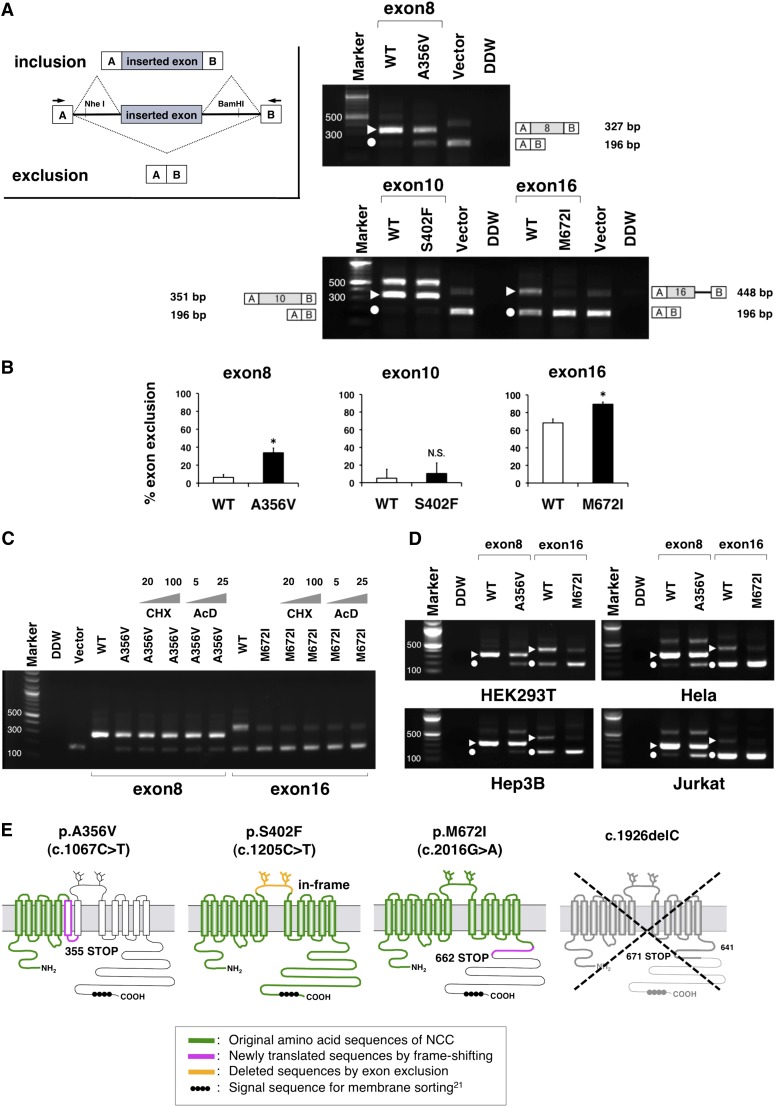

On the basis of this bioinformatics data, we next performed in vitro splicing assay using minigenes.12 Minigenes, which contain a conventional expression system with two cassette exons, are designed to allow analysis of the resultant mRNA transcripts (inset of Figure 2A). A hybrid minigene mainly produces two transcripts. One is composed of exon A, as an inserted exon along with exon B (upper), and the other is composed of exon A and B (lower). After the minigenes inserted with the p.A356V, p.S402F, and p.M672I fragments were transfected into human kidney HEK293T cells, total RNA was extracted and transcribed to cDNA. PCR was performed using flanking primers (arrows in Figure 2A) and then visualized on an agarose gel (Figure 2A). As a result, the amounts of the exon-excluded p.A356V and p.M672I transcripts were significantly increased compared with those of the control plasmids, whereas there was no significant change in p.S402F (Figure 2B). These data strongly suggest that the exonic mutations of p.A356V and p.M672I disturbed the normal splicing in vitro.

Figure 2.

Hybrid minigene assay reveled the aberrant exonic mRNA splicing in GS syndrome. (A) RT-PCR amplified products of hybrid minigene transcripts in HEK293T cells. The transcripts produced by the hybrid minigene are schematically shown and the arrows show the primers used to amplify (inset). The triangles and circles indicate the transcripts of exon inclusion and the exclusion, respectively. The sizes of the exon-included transcripts included 327 nucleotides for exon 8, 351 for exon 10, and 448 for exon 16. There were some defectively spliced fragments including partial introns on the exon 10 lane (575 nucleotides) and on the vector lane (407 nucleotides). The identity of each fragment is illustrated schematically on the side. (B) Quantification of the splicing percentage in the graph was densitometrically calculated on a molar basis as the percentage of exclusion (%)=(lower band/[lower band+upper band])×100.15 Error bars represent SEM (n=3). *P<0.05, unpaired t test. (C) The treatment with de novo protein synthesis inhibitors indicates that the transcriptional products are stable. The gray triangles represent the concentrations of the reagents in a dose-dependent manner. AcD, actinomycin D; CHx, cycloheximide. (D) Comparison among the other cell types in the RT-PCR products of the minigene transcripts. Transfection of the hybrid minigenes to Hela, Hep3B, and Jurkat cell lines was performed the same as for HEK293T. The triangles and circles indicate the transcripts of exon inclusion and exclusion, respectively. (E) Predicted protein structures translated from the aberrant transcripts of the exon exclusions. Once the c.1067C>T mutation induces the exon8 exclusion, the frameshift and prematurely terminated codon occur in the transmembrane domain. The c.2016G>A mutation also induces the exon16 exclusion, resulting in a truncated protein that lacks a large part of the carboxyl terminal domain, which contains the signal sequence required for normal translocation. The c.1926delC allele is expected to be unstable because of mRNA degradation.

To elucidate whether the transcripts produced by the minigenes were vulnerable to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), we used two de novo protein synthesis inhibitors (Figure 2C). It is reported that the volume or size of the transcripts related to NMD may be changed by the use of certain reagents.19,20 As shown in Figure 2C, treatment with cycloheximide or actinomycin D had no effect on these artificial transcripts. These data indicate that the transcripts derived from minigenes would be independent of NMD process.

To determine whether these transcriptional changes also occur commonly in other tissues, we next used different cell lines (Hep3B as hepatocytes, Hela as cervical cells, and Jurkat as lymphoblasts). As a result, the proportional changes of the exon exclusion in these three cell lines were similar to that in HEK293T (Figure 2D). This suggests that exon exclusions triggered by single nucleotide alterations take place in a variety of tissues.

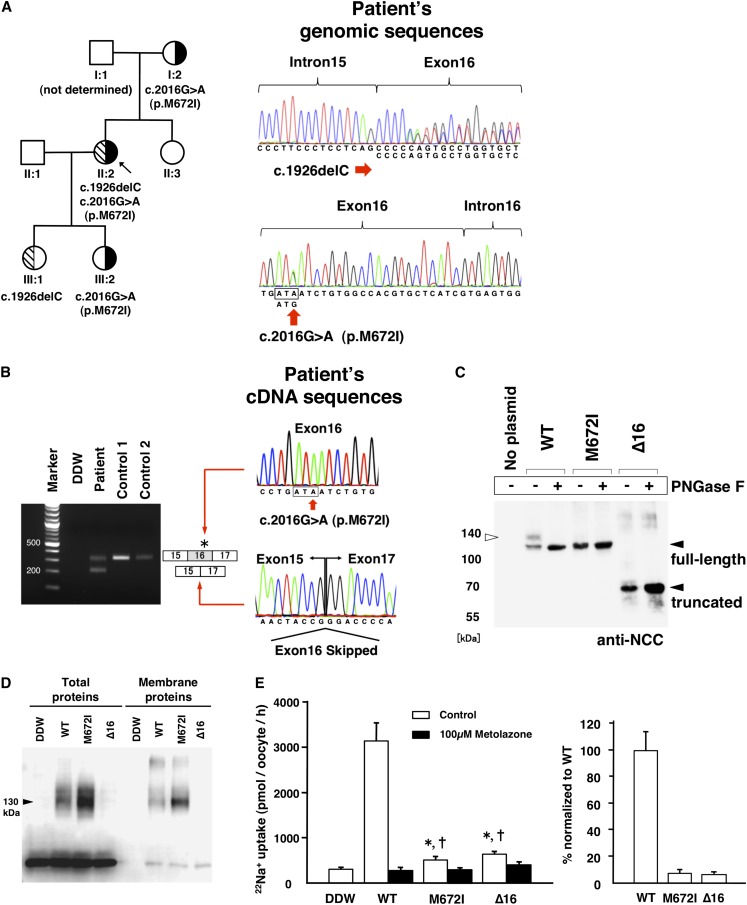

If the exon-excluded transcripts of the SLC12A3 gene were successfully translated, protein truncations would be expected because of the presence of a premature termination codon (Figure 2E). Because NCC harbors a signal sequence near the end of the carboxyl terminal domain,21 these partial truncations may cause critical problems in membrane translocation and function of NCC (Figure 2E). Therefore, we further investigated whether putative exon skipping really led to GS in an actual patient. Recently, we encountered a Japanese patient with GS who had compound heterozygous mutations in the SLC12A3 gene. Upon genomic DNA sequencing (Figure 3A), one allele had a c.2016G>A (p.M672I) mutation within exon16 and the other allele had a single cytosine deletion at the 5′ end of exon16 (c.1926delC). The cDNA from the peripheral blood was amplified by PCR with primers spanning exon 15 to exon 17, and doublet fragments were uniquely detected from the patient’s cDNA. Upon cDNA sequencing, the larger amplicon was the exon 16–included transcript with the c.2016A allele and the smaller one was the exon 16–excluded transcript (Figure 3B). Notably, the c.2016G allele with c.1926delC was not observed upon cDNA amplification. TA cloning of the larger amplicon was performed to detect the c.2016G allele. Fifteen colonies were selected, and all of the 15 clones sequenced were found to be c.2016A maternal alleles. These data suggest that the c.2016A allele produced both the p.M672I mutated transcript and the exon16-excluded one, and that two kinds of mutant proteins were thus generated.

Figure 3.

Resultant exotic splicing in the GS syndrome causes loss of function mutation. (A) A family pedigree along with the candidates for exon skipping are shown (left panel). The index patient (arrow) had a compound heterozygous c.[1926delC];[2016G>A] in the SLC12A3 gene. The carriers are shown in half boxes with oblique lines (c.1926delC) and in half-blackened boxes (c.2016G>A). The genomic sequences of the patient are illustrated (right panel). The upper genome sequence indicates one nucleotide deletion of cytosine at the 5′ end of exon16. The lower sequence shows the heterozygous G to A substitution (p.M672I) 22 nucleotides upstream of the 3′ end of exon16. (B) The products of semi-nested PCR with cDNA from the peripheral blood (left panel). The sizes of the two fragments were 310 and 198 nucleotides. The two fragments were directly sequenced (right panel). The larger fragment indicates the normally spliced transcript derived from the c.2016A allele. The smaller fragment shows the exon16-excluded transcript. DNA from Japanese (control 1) and white (control 2) persons was used as controls. (C) Immunoblotting of total cell lysate transfected with the WT or mutant plasmids with the N-glycosidase F treatment in HEK293T. The open and solid arrowheads indicate the protein sizes of the glycosylated and nonglycosylated monomers, respectively. (D) Cell surface biotinylation of the Xenopus oocytes. A representative example of total and biotinylated proteins from oocytes injected with water, WT, or mutant NCC as stated. No NCC expression was observed in water-injected oocytes. A broad band was detected in both total and membrane protein for both WT and p.M672I mutant NCC. Note that in total proteins the p.M672I band runs faster than WT NCC, indicating different pattern of glycosylation. (E) 22Na+ uptake assay with Xenopus oocytes. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. Each bar represents a mean value of uptake±SEM of 10 oocytes from a single toad. *P<0.0001 versus the value of WT and †P<0.05 versus the value of DDW (unpaired t test). The net uptake activities are represented as the values of the presence (solid bars) and the absence (open bars) of 0.1 mM metolazone in the left panel. Each of the thiazide-sensitive uptake activity is calculated as a subtraction of solid bars from open bars in the right panel (WT was set as 100%).

To examine the functional activities of these mutant NCCs in the patient with GS, two plasmids with the single amino acid substitution and exon 16 deletions (depicted as ∆16) were constructed and assessed. First, to examine abnormal sorting to the plasma membrane, the HEK293T cell lysates were treated with N-glycosidase F. In the transiently transfected cells, the truncated protein was detected by immunoblotting and both mutants were remarkably less glycosylated than the wild-type (WT) NCC (Figure 3C). The assessment of the p.A356V mutation was omitted because the predicted protein translated from the exon8-excluded transcript would lack glycosylated moieties. Second, we performed cell surface biotinylation assay with Xenopus laevis oocytes and injected each of the cRNAs to observe the membrane trafficking of mutant NCCs. The p.M672I amino acid substitution was able to reach the plasma membrane of the oocytes; however, normal expression and sorting to the membrane were not observed in the deletion mutant (Figure 3D). Third, the 22Na+ uptake activity in the mutants was measured using a Xenopus oocyte expression system. Both amino acid substitution and exon exclusion abrogated the uptake activity (Figure 3E).

These data suggest that the single mutation in exon16 results in nonfunctional transcripts due to exon skipping.

We determined via a combination of in silico and in vitro assays that an exonic point mutation in the genome caused exon skipping in the SLC12A3 transcripts from a patient with GS.

Many missense mutations in the SLC12A3 gene have been experimentally assessed by amino acid substitutions. However, when functional characterization of the artificially mutated proteins is ambiguous, the mutation has probably been considered a silent polymorphism, with no explanation for the loss of function.22 Therefore, many investigators have focused their attention on the other potential mechanisms, for example, large genomic rearrangements and mutations likely affecting regulatory elements, such as the promoter, enhancer, and deeper intronic regions. In this study, we investigated an alternative genetic mechanism—exon skipping due to ESE disruption—for the remaining missense mutations that were unidentified, which were assumed to masquerade as missense mutations. Consequently, we found that the c.2016G>A exonic mutation caused both exon skipping and amino acid alteration in the SLC12A3 gene.

Among three candidates selected by the ESEfinder program in silico, two mutations (p.A356V in exon 8 and p.M672I in exon 16) caused exon skipping in vitro. One p.S402F mutation allowed exon 10 to be included. The ESEfinder software was programmed to predict exon skipping by scoring the sequences matched with the putative ESEs, as previously reported.23,24 The ESEs effectively contribute to the exons with the authentic splice sites displaying reduced homology with the consensus sequences. We therefore assessed the homology of all of the splice sites in the SLC12A3 gene to identify the vulnerable exons depending on the ESEs, as described in a previous article, using the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project splicing predictor program (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html).9 These analyses revealed that exon 8 had a weak 3′ acceptor site and exon16 had a weak 5′ donor site (Supplemental Table 2).

On the basis of the fundamental mechanism of exon skipping, our study showed that exon 10 possessed strong 5′ donor and 3′ acceptor sites. This finding suggests that the exon-intron boundaries of exon 10 may be correctly recognized without the need for any assistance of the ESEs. These data also agree with the experimental results shown in Figure 2A.

In addition, Lo et al. have reported that deep intronic mutations also result in aberrant splicing in the SLC12A3 transcript.25 Hence, to rule out the possibility that deep intronic mutations affected the splicing events, we verified by genomic sequencing that there were no specific single nucleotide polymorphisms in the flanking introns of exon 16 in our patient (data not shown). This suggests that the exon skipping in this patient is exclusively due to the c.2016G>A single nucleotide mutation.

In our patient, the WT c.2016G allele with the c.1926delC was not observed in cDNA amplification. To confirm the allelic specificities of the c.1926delC and c.2016G, we read each of the exonic sequences in the patient’s genome from exon 1 to exon 15 and detected one single nucleotide polymorphism, rs2304479, in exon 2 (Supplemental Figure 1). PCR amplification of the cDNA derived from the patient’s blood confirmed that the one heterozygous allele was absent. Consequently, the pedigree analysis showed that the c.1926delC allele is directly linked to c.2016G (Supplemental Figure 1). These results provide evidence that the transcript derived from c.2016G allele is unstable because of the single nucleotide deletion, and that the c.2016A allele yields both the p.M672I mutated transcript and the exon 16–excluded one.

We prepared cDNA constructs as expected according to prediction of the p.M672I mutated transcript and the exon 16 exclusion and tested for functional activity and cell surface expression. The p.M672I mutated construct produced the nonglycosylated NCC protein and it displayed no uptake, even though some of it reached the cell surface in the case of transient transfection, indicating that some of the p.M672I mutant NCC does reach the membrane. Its conformational state precludes any activity as a cotransporter, similar to the situation that has been shown to occur when other mutations of NCC are located in the carboxyl terminal domain.6 The exon 16–excluded plasmid successfully produced the abnormally truncated protein in transient transfection into culture cells (Figure 3C). On the other hand, cRNA injection into oocytes failed to produce any protein (Figure 3D). The discrepancy between the expression patterns of the exon 16–excluded construct apparently depends on the balance between the production and degradation of the abnormal intracellular proteins.

We extracted both genomic DNA and RNA from blood. Because it is well known that NCC is predominantly expressed in the distal convoluted tubules of the kidney, we suspected that the regulatory function of the NCC in the blood leukocytes would be the same as in epithelial cells. To observe the splicing event under more natural intracellular conditions, we collected urine samples from the patient with GS and performed the splicing assay. However, no fragment was amplified from the urine sediment under the conditions used (data not shown). Further investigation is needed to determine the actual splicing events in the kidney.

In this study, we found that exon skipping was associated to a certain extent with the molecular pathology of abnormal protein production in GS. A therapeutic approach that normalizes such aberrant splicing through the administration of specific reagents may apply to patients with GS who have these mutations.13

Taken together, these findings reveal that exonic mutations caused exon skipping in the SLC12A3 transcript by the combination of in silico and in vitro assays. The concept of exon skipping due to ESE disruption provides an alternative approach to the functional analysis of the missense mutations responsible for GS.

CONCISE METHODS

Materials

HEK293T, Hep3B, Hela, and Jurkat cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cycloheximide and actinomycin D were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Ouabain octahydrate, amiloride hydrochloride, bumetanide, and metolazone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

In Silico Splicing Assay

ESEfinder is a web resource that uses experimentally defined score matrices to identify putative ESEs in DNA sequences (http://rulai.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/tools/ESE3/esefinder.cgi?process=home). The 88 missense mutations of the SLC12A3 gene selected from the PubMed database were analyzed with the ESEfinder3.0 SR protein matrix (threshold scores of SRSF1: 1.956 as default status, SRSF2: 2.383, SRSF5: 2.67, SRSF6: 2.676). Furthermore, we removed the missense mutations predicted to affect the consensus 5′ donor or 3′ acceptor site by the ESEfinder3.0 splice site matrix program or the missense mutations characteristically identified in previous articles. We finally chose the mutations exhibiting significant reductions of two or more ESE scores to below the selection threshold.

Plasmid Construction

For the in vitro splicing assay, the target exons (8, 10, and 16) including approximately 150 nucleotides flanking shortened introns with NheI and BamHI restriction sites were amplified from the purchased human genome (Promega, Madison, WI). Both edges of the shortened introns were properly designed by the Human Splicing Finder program (http://www.umd.be/HSF/) so as to avoid the activation of cryptic splicing. The primers used in this study were edited by Primer3 software (http://primer3plus.com/cgi-bin/dev/primer3plus.cgi) and are listed in Supplemental Table 3. Each amplified fragment was inserted into a pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by a TA Cloning kit (Life Technologies), and the targeted mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. All of the indicated fragments were ligated into a minigene construct with the NheI and BamHI restriction sites (H492, provided by Dr. Takeshima, Kobe University26). NCC variant 3 (Genbank association number NM_001126108.1) was used as a reference sequence, in which the A of ATG is denoted as coding region number 1.

For the expression assay and functional assay, the full-length NCC was amplified from a human MTC panel kidney library (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The p.M672I single amino acid substitution was generated by DpnI site-directed mutagenesis. The exon 16–excluded mutant was generated by deletion mutagenesis and by being connected the subsequent premature termination codon with the restriction site of indicated vectors. The WT and mutated NCC fragments were inserted into a FLAG-tagged pcDNA3 mammalian vector (provided by Dr. Kobayashi, Tohoku University.) for the expression assay in HEK293T and into a pGEMHE Xenopus oocyte expression vector27 for the functional assay, respectively.

In Vitro Splicing Assay

HEK293T and Hela cells were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Hep3B and Jurkat cells were grown in RPMI with the same supplements as above. After spreading the cells in six-well plates, the 1.6 µg/well plasmids were transfected with 4.0 µl/well Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Thirty-six hours after transfection, total RNA was extracted using Tripure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and the residual genome was completely digested with DNase I (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was transcribed with a Transcriptor First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche). PCR was performed with the forward primer corresponding to upstream exon A and the reverse primer complementary to downstream exon B, as previously described.26

To evaluate the influence of NMD, cycloheximide (20, 100 µg/ml as the final concentration) and actinomycin D (5, 25 µg/ml) were added to the media 8 hours before total RNA extraction.

Profile of a Patient with GS and Sequencing of DNA and RNA from the Peripheral Blood

The patient with GS was a 42-year-old Japanese woman referred for evaluation of prolonged headache and chest discomfort. The symptoms first occurred at age 30 years. Her ambulatory BP was 99/75 mmHg. The biochemical analysis provided the following: hypokalemia with no medication (2.0 mEq/L), hypomagnesemia (1.3 mg/dl), elevation of plasma renin activity (27.6 ng/ml per hour; normal range, 0.2–2.7), and serum aldosterone concentration (240 pg/ml; normal range, 30–159). The result of arterial blood gas analysis was pH of 7.532. All the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of adult-onset GS. Peripheral blood was collected from the patient under the approval of the ethical committee of Tohoku University and Nihon University. The buffy coat was separated from the blood by centrifugation. Total RNA was extracted by Tripure, followed by the treatment with DNase I as described above. RNA was condensed by repetitive filtration using RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen). The first PCR was carried out using a LightCycler (Roche) with FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche). The second semi-nested PCR was performed using a ThermalCycler (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan) with PrimeStar GXL DNA polymerase (Takrara).

Immunoblotting

Forty-eight hours after transfection, the HEK293T cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Ten micrograms of protein denatured by 1.0 mM dithiothreitol was incubated with N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) at 37°C for 1 hour. The samples were separated on 8% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Blots were blocked by 1% nonfat milk in PBS, including 0.5% TritonX100, at room temperature for 1 hour and then probed with an anti-human NCC antibody (1:2000 dilution; Merck, Dermstadt, Germany) at 4°C overnight. The blots were washed and incubated with an anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution; Pierce, Rockford, IL). An enhanced chemiluminescence plus chemiluminescent system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was used for detection.

Oocyte Cell Surface Biotinylation

Cell surface expression of WT and mutant NCC were assessed as previously described in detail.28 In brief, Xenopus laevis oocytes injected with WT or mutant NCC cRNA were washed 5 times in ND96 Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer and incubated for 30 minutes with Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C. After five washes, oocytes were homogenized in a sucrose-based buffer (4 µl/oocyte) containing 10 µl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) using a 25-G needle. Streptavidin precipitation was done using 500 µg of protein from biotinylated oocytes and was diluted in 1 ml Tris-buffered saline and 50 µl streptavidin agarose beads, 50% slurry (Upstate, Cell Signaling Solutions) were added. Samples were rolled overnight at 4°C. Beads were then washed one time with Buffer 1 (5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH, 7.4]), twice with Buffer 2 (500 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH, 7.4]), and once with Buffer 3 (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH, 7.4]), with a 2-minute 4000 G centrifugation between washes. After the last wash, Buffer 3 was substituted with 30 µl RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein samples were heated to 65°C for 15 minutes before separation on a 7.5% acrylamide gel.

Assessment of NCC Function

The WT and mutated NCC activities were assessed by functional expression in Xenopus oocytes following the protocols published previously.29 In brief, water, WT, or mutant NCC cRNA (10 ng/oocyte) was injected into the defolliculated oocytes. Oocytes were maintained for 2 days in isotonic ND96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES/Tris [pH, 7.4]). The night before the uptake assay, oocytes were incubated in a low chloride buffer (96 mM Na+ isethionate, 2 mM K gluconate, 1.8 mM Ca gluconate, 1 mM Mg gluconate, and 5 mM HEPES [pH, 7.4; 170 mOsm/kg H2O]). 22Na+ uptake (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) was assessed in oocytes exposed to isotonicity using the isotonic uptake buffer (40 mM NaCl, 56 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine-chloride, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM HEPES [pH, 7.4; 210 mOsm/kg H2O]) containing 1 mM ouabain, 0.1 mM amiloride, and 0.1 mM bumetanide plus 2.0 µCi/ml of 22Na+. Tracer activity was determined for each oocyte by gamma counting.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shoji Tsutaya and Minoru Yasujima (Hirosaki University) for analyzing the genomic data of the patient’s family, Toru Kikuchi (Shichinohe Public Hospital) for obtaining the patient’s blood, and the patient with GS for her kind participation in this study. This work was supported in part by National grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (23390033); the Japan Kidney Foundation the S Foundation and the Miyagi Kidney Foundation; and grants 165815 and 180075 from Conacyt (Mexico) to G.G.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013091013/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Bia MJ, Ellison D, Karet FE, Molina AM, Vaara I, Iwata F, Cushner HM, Koolen M, Gainza FJ, Gitleman HJ, Lifton RP: Gitelman’s variant of Bartter’s syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet 12: 24–30, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glaudemans B, Yntema HG, San-Cristobal P, Schoots J, Pfundt R, Kamsteeg EJ, Bindels RJ, Knoers NV, Hoenderop JG, Hoefsloot LH: Novel NCC mutants and functional analysis in a new cohort of patients with Gitelman syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 20: 263–270, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jong JC, Van Der Vliet WA, Van Den Heuvel LP, Willems PH, Knoers NV, Bindels RJ: Functional expression of mutations in the human NaCl cotransporter: Evidence for impaired routing mechanisms in Gitelman’s syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1442–1448, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riveira-Munoz E, Chang Q, Godefroid N, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Dahan K, Devuyst O, Belgian Network for Study of Gitelman Syndrome : Transcriptional and functional analyses of SLC12A3 mutations: New clues for the pathogenesis of Gitelman syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1271–1283, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunchaparty S, Palcso M, Berkman J, Velázquez H, Desir GV, Bernstein P, Reilly RF, Ellison DH: Defective processing and expression of thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter as a cause of Gitelman’s syndrome. Am J Physiol 277: F643–F649, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabath E, Meade P, Berkman J, de los Heros P, Moreno E, Bobadilla NA, Vázquez N, Ellison DH, Gamba G: Pathophysiology of functional mutations of the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter in Gitelman disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F195–F203, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR: Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: Exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat Rev Genet 3: 285–298, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu HX, Cartegni L, Zhang MQ, Krainer AR: A mechanism for exon skipping caused by nonsense or missense mutations in BRCA1 and other genes. Nat Genet 27: 55–58, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zucker M, Rosenberg N, Peretz H, Green D, Bauduer F, Zivelin A, Seligsohn U: Point mutations regarded as missense mutations cause splicing defects in the factor XI gene. J Thromb Haemost 9: 1977–1984, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raponi M, Kralovicova J, Copson E, Divina P, Eccles D, Johnson P, Baralle D, Vorechovsky I: Prediction of single-nucleotide substitutions that result in exon skipping: Identification of a splicing silencer in BRCA1 exon 6. Hum Mutat 32: 436–444, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartegni L, Krainer AR: Disruption of an SF2/ASF-dependent exonic splicing enhancer in SMN2 causes spinal muscular atrophy in the absence of SMN1. Nat Genet 30: 377–384, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heintz C, Dobrowolski SF, Andersen HS, Demirkol M, Blau N, Andresen BS: Splicing of phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) exon 11 is vulnerable: molecular pathology of mutations in PAH exon 11. Mol Genet Metab 106: 403–411, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Blanco MA, Baraniak AP, Lasda EL: Alternative splicing in disease and therapy. Nat Biotechnol 22: 535–546, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avila AM, Burnett BG, Taye AA, Gabanella F, Knight MA, Hartenstein P, Cizman Z, Di Prospero NA, Pellizzoni L, Fischbeck KH, Sumner CJ: Trichostatin A increases SMN expression and survival in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Clin Invest 117: 659–671, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hastings ML, Berniac J, Liu YH, Abato P, Jodelka FM, Barthel L, Kumar S, Dudley C, Nelson M, Larson K, Edmonds J, Bowser T, Draper M, Higgins P, Krainer AR: Tetracyclines that promote SMN2 exon 7 splicing as therapeutics for spinal muscular atrophy. Sci Transl Med 1: 5ra12, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taniguchi-Ikeda M, Kobayashi K, Kanagawa M, Yu CC, Mori K, Oda T, Kuga A, Kurahashi H, Akman HO, DiMauro S, Kaji R, Yokota T, Takeda S, Toda T: Pathogenic exon-trapping by SVA retrotransposon and rescue in Fukuyama muscular dystrophy. Nature 478: 127–131, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt H, Kabesch M, Schwarz HP, Kiess W: Clinical, biochemical and molecular genetic data in five children with Gitelman’s syndrome. Horm Metab Res 33: 354–357, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reissinger A, Ludwig M, Utsch B, Prömse A, Baulmann J, Weisser B, Vetter H, Kramer HJ, Bokemeyer D: Novel NCCT gene mutations as a cause of Gitelman’s syndrome and a systematic review of mutant and polymorphic NCCT alleles. Kidney Blood Press Res 25: 354–362, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong Q, Zhang L, Vincent GM, Horne BD, Zhou Z: Nonsense mutations in hERG cause a decrease in mutant mRNA transcripts by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in human long-QT syndrome. Circulation 116: 17–24, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santamaria R, Vilageliu L, Grinberg D: SR proteins and the nonsense-mediated decay mechanism are involved in human GLB1 gene alternative splicing. BMC Res Notes 1: 137, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaarour N, Demaretz S, Defontaine N, Mordasini D, Laghmani K: A highly conserved motif at the COOH terminus dictates endoplasmic reticulum exit and cell surface expression of NKCC2. J Biol Chem 284: 21752–21764, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naraba H, Kokubo Y, Tomoike H, Iwai N: Functional confirmation of Gitelman’s syndrome mutations in Japanese. Hypertens Res 28: 805–809, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han J, Ding JH, Byeon CW, Kim JH, Hertel KJ, Jeong S, Fu XD: SR proteins induce alternative exon skipping through their activities on the flanking constitutive exons. Mol Cell Biol 31: 793–802, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho PY, Huang MZ, Fwu VT, Lin SC, Hsiao KJ, Su TS: Simultaneous assessment of the effects of exonic mutations on RNA splicing and protein functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 373: 515–520, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo YF, Nozu K, Iijima K, Morishita T, Huang CC, Yang SS, Sytwu HK, Fang YW, Tseng MH, Lin SH: Recurrent deep intronic mutations in the SLC12A3 gene responsible for Gitelman’s syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 630–639, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thi Tran HT, Takeshima Y, Surono A, Yagi M, Wada H, Matsuo M: A G-to-A transition at the fifth position of intron-32 of the dystrophin gene inactivates a splice-donor site both in vivo and in vitro. Mol Genet Metab 85: 213–219, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P: Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron 9: 861–871, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arroyo JP, Lagnaz D, Ronzaud C, Vázquez N, Ko BS, Moddes L, Ruffieux-Daidié D, Hausel P, Koesters R, Yang B, Stokes JB, Hoover RS, Gamba G, Staub O: Nedd4-2 modulates renal Na+-Cl- cotransporter via the aldosterone-SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1707–1719, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pacheco-Alvarez D, Cristóbal PS, Meade P, Moreno E, Vazquez N, Muñoz E, Díaz A, Juárez ME, Giménez I, Gamba G: The Na+:Cl- cotransporter is activated and phosphorylated at the amino-terminal domain upon intracellular chloride depletion. J Biol Chem 281: 28755–28763, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.