Abstract

The mountain peacock pheasant (Polyplectron inopinatum), the Malayan peacock pheasant (Polyplectron malacense), and the Congo peafowl (Afropavo congensis), are all listed as vulnerable to extinction under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Here we report fatal infection with a novel herpesvirus in all three species of birds. DNA was extracted from the livers of birds with hepatocellular necrosis and intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions consistent with herpesvirus infection. Using degenerate herpesvirus primers and polymerase chain reaction, 220 and 519 base pair products of the herpes DNA polymerase and DNA terminase genes, respectively, were amplified. Sequence analysis revealed that all birds were likely infected with the same virus. At the nucleotide level the pheasant herpes virus had 92% identity with Gallid herpesvirus 3 (GaHV-3) and 77.7% identity with Gallid herpesvirus 2 (GaHV-2). At the amino acid level the herpes virus had 93.8% identity with GaHV-3 and 89.4% identity with GaHV-2. These findings indicate that the closest relative to this novel herpesvirus is GaHV-3, a non-pathogenic virus used widely in a vaccine against Marek’s disease. In situ hybridization using probes specific to the peacock pheasant herpesvirus DNA polymerase revealed strong intranuclear staining in the necrotic liver lesions of an infected Malayan peacock pheasant, but no staining in normal liver from an uninfected bird. The Phasianid herpesvirus reported here is a novel member of the genus Mardivirus of the subfamily alphaherpesvirinae, and is distinct from other galliform herpesviruses.

Keywords: Congo peafowl, herpesvirus, Malayan peacock pheasant, mardivirus, Mountain peacock pheasant

Herpesviruses are among the largest and most complex of viruses. Their double stranded DNA genome, ranging between 125–250 kilobases (kb), is encapsulated within an icosahedral protein capsid and a tegument matrix.6,7,13 Viral DNA replication and assembly of capsid structures occurs in the nucleus of the cells, and viral particles become enveloped by lipids as they transit out of the nucleus.2 In some host cells, the virus can remain dormant for long periods of time through the active transcription of genes associated with latency. During symptomatic or lytic infection, or reactivation, the production and release of the virions results in destruction and necrosis of the host cells. The virions are subsequently released leading to infection of other cells. In nature, each virus is associated with a distinct host species suggesting that herpesviruses co-evolve with their hosts over long periods of time, and thus are extremely well-adapted to them.6,13

Herpesviridae are divided into three distinct subfamilies, Alphaherpesvirinae, Betaherpesvirinae and Gammaherpesvirinae, based on biological and molecular properties and genomic sequence divergence.6,13 Alphaherpesviruses have a more rapid cytolytic productive cycle than beta- and gammaherpesviruses.8 All taxonomically assigned avian herpesviruses belong to the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily, and are grouped in the Iltovirus or Mardivirus genera.20 Phylogenetic estimates suggest that avian iltoviruses appeared about 200 million years ago, and that avian mardiviruses and mammalian simplex viruses appeared between 100–150 million years ago.13 Mardiviruses such as Gallid herpesvirus 2 (GaHV-2 or Marek’s disease virus 1), Gallid herpes virus 3 (GaHV-3 or Marek’s disease virus-2), and Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 (MeHV-1), and iltoviruses notably Gallid herpesvirus 1 (GaHV-1), have been characterized in several species of gallinacous birds.1,11,17,20 Herpesvirus infections have also been reported and cause disease in peacock pheasants and Congo peafowl, and the same gross and microscopic lesions seen in pheasants were produced in healthy chickens inoculated with the pheasant viral isolate.14 Work by Gunther et. al. attempted to classify a tragopan herpesvirus using restriction endonuclease analysis; however the unique restriction pattern exhibited by the virus revealed a high dissimilarity to other known avian herpesviruses.9 To date, no studies have taxonomically classified a pheasant herpesvirus based on molecular phylogeny.9,14 We describe the molecular characterization of a novel alphaherpesvirus of the genus Mardivirus that resulted in death in three species of pheasants.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Histology

Archived pathology records for gallinacous birds from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) collection that died between 1994 and 2002 were reviewed. Birds with a histologic diagnosis of hepatocellular necrosis with intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions suggestive of herpesvirus infection met the inclusion criteria. These cases included 8 mountain peacock pheasants (case Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 12), 3 Malayan peacock pheasants (case Nos. 5, 6, 11), and 1 Congo peafowl (case No. 7).

The pheasants were all housed at the Bronx Zoo, NY, singly or in pairs with conspecifics. Some were co-housed in the same enclosures with or adjacent to other genera of birds. Enclosures were located in two buildings and birds were occasionally moved between those buildings to achieve management goals. Birds were housed in enclosures with free access to indoor or outdoor environments with the exception of periods of inclement weather during which birds were housed indoors. No common of exposure to other taxa or individual birds was found in affected birds. No recent introductions of birds into adjacent enclosures occurred. Affected birds either died or presented acutely with non-specific clinical signs. Supportive treatment, including subcutaneous fluids, antibiotics and vitamins were administered to early cases. After herpesvirus infections were documented, antiviral treatment with acyclovir was initiated as well. Treatment did not affect outcome. Upon death, each bird was submitted for gross necropsy and tissue from the liver, spleen, intestines, kidneys, brain, adrenals, thymus, lungs, bone marrow, heart, tongue, trachea, crop, ventriculus, proventriculus, eyes, and pancreas were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for routine brightfield microscopy. Two Malayan peacock pheasants that died of non-infectious causes, including trauma and tracheal obstruction (case Nos. 13 and 14), were used as non-herpes infection controls for both histology and in situ hybridization.

Herpesvirus PCR

To determine if the diseased pheasants were infected with herpesviruses, DNA was extracted from a total of 25 µm (5 sections × 5 µm each) of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) liver tissue using the QIAamp DNA extraction kit (Qiagen Inc.; Valencia, CA, USA). The DNA was subjected to nested PCR using degenerate primers designed to detect herpesvirus DNA polymerase and DNA terminase. DNA extracted from livers of 2 normal Malayan peacock pheasants (case Nos. 13 and 14) were used as negative controls. Primers were purchased from Eurofins (Eurofins MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL, USA), and all PCR reagents were purchased from Qiagen (Qiagen Inc.; Valencia, CA, USA) unless otherwise specified. Nested PCR was used to amplify a 519 bp region (first round) and a 419 bp region (second round) of DNA terminase,5 and a 220bp fragment of DNA polymerase.21 Human herpesvirus 1 DNA was used as a positive control. The following reagents were added to each 50 µl PCR reaction: 5 µl of extracted DNA (> 20 ng/µl) for the first round (or 5 µl of primary PCR mixture for the second round), 1 µM of each primer, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 µM each of dNTP’s, 1.5 U of Hotstart Taq Polymerase, 5 µl of 10 X PCR buffer, and 5 % DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cycling parameters for both methods of PCR used an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds, 46°C for 60 seconds, 72°C for 60 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. Primary and secondary PCR products of correct molecular weight (220 bp for DNA polymerase and 519 bp for DNA terminase) were spliced out of the agarose gel and purified using the MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen Inc.; Valencia, CA, USA) followed by direct sequencing in both directions using an ABI 3730×/DNA analyzers for capillary electrophoresis and fluorescent dye terminator detection (Genewiz Inc., South Plainfield, NJ, USA).

Nucleotide and protein sequences were submitted to BLASTn and BLASTx to identify sequence homologies within the Genbank database (GenBank, National Center for Biotechnology Information). Sequences from the herpesvirus positive peacock pheasants (n=8) and the positive peacock (n=1) were aligned at the nucleotide and protein level (Geneious Pro 5.1.7 software, Biomatters LTD., Auckland, NZ).

Phylogenetic analysis

To determine the phylogenetic relationship of peacock herpesvirus to described alpha, beta, and gamma herpesviruses, protein sequences from representative species were retrieved from GenBank and aligned with the translated Malayan peacock (case No. 11) herpesvirus DNA terminase or DNA polymerase sequence using the Geneious alignment tool (Geneious Pro ™ 5.1.7 software, Biomatters LTD., Auckland, NZ). Sequences for comparison were trimmed to 162 amino acids for the DNA terminase and 46 amino acids for the DNA polymerase. To obtain pair-wise identities between herpesvirus species, the protein alignment for DNA terminase was run through PAUP (Phyogenetic Analaysis Using Parsimony, version 4b10osx, Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers, Sunderland, MA, USA) to generate a running P-distance pairwise comparison matrix. Bayesian analysis was performed using MrBayes 3.1 plugin on Geneious Pro™ software using gamma distributed rate variation and a Poisson rate matrix.10 The first 25% of a 1,100,000 chain length was discarded as burn-in, and 4 heated chains were run with a sub-sampling frequency of 200. GenBank accession numbers for the DNA terminase are listed in Fig. 6. The nucleotide sequence for Phasianid herpesvirus DNA terminase was deposited in GenBank under accession number JN127369. For DNA polymerase, GenBank accession numbers are as follows: AF168792_3, Gallid herpesvirus 1; ACR02982, Gallid herpesvirus 2; BAB16540, Gallid herpesvirus 3; HVT038, Meleagrid herpesvirus 1; ABM92130, Anatid herpesvirus 1; AAU88096, Cercopithecine herpesvirus 2; NP_851890, Macacine herpesvirus 1; YP_443877, Papiine herpesvirus 2; CAA26941, Human herpesvirus 1; ADM52140, Human herpesvirus 2; AAS45914, Equid herpesvirus 1; ACT88328, Felid herpesvirus 1; AAN64026, Psittacid herpesvirus 1.

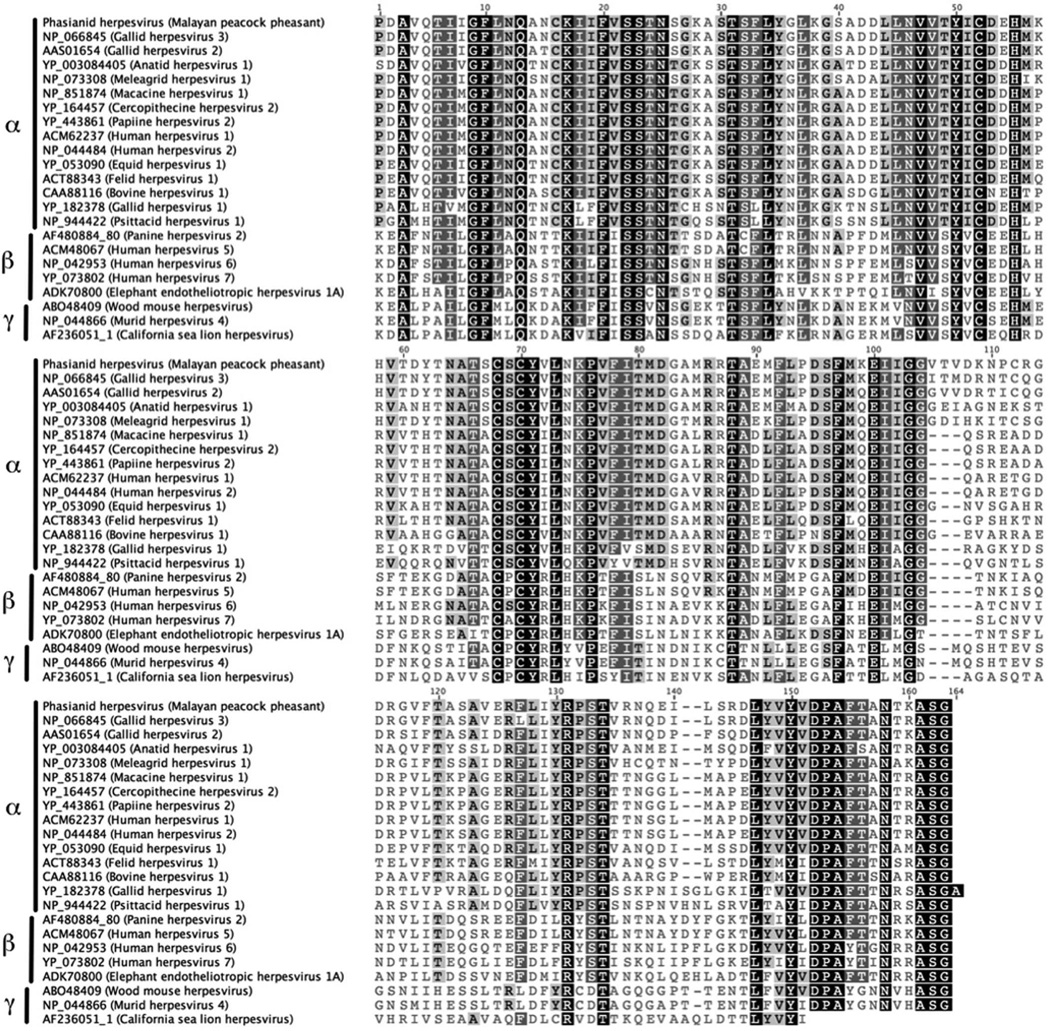

Figure 6.

Protein alignment of a 163 amino acid sequence of DNA Terminase. Amino acids indicated in black indicate 100% similarity in the alignment, dark grey-80–100% similar, light grey-60–80% similar, and white-less than 60% similar using an identity score matrix (Geneious Pro™ software). GenBank accession numbers used for all species precedes the name of the herpesvirus species.

In Situ Hybridization

Probes to a 151 nucleotide sequence of DNA polymerase from Polyplectron malacense malacense and an 872 nucleotide sequence of beta-actin from Maleagris gallopavo, used as an internal housekeeping gene control, were hybridized to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 5 µm sections from infected or non-infected Malayan peacocks (Affymetrix, QuantiGene ViewRNA, Sanata Clara, CA). Sections on positively charged glass microscope slides (Surgipath Medical Ind., Richmond IL) were heated at 60°C for 30 minutes in a Statspin Thermobrite slide hybridizer (Iris Sample Processing®, Westwood, MA, USA) to increase adhesion of the tissue to the slide. The slides were then fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin solution for 1 hour and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and allowed to air dry. The slides were subsequently heated at 80°C for three minutes to melt the paraffin, and the paraffin was dissolved and removed using citrate. The slides were washed in 95% ethanol and air dried, submerged in 1X pretreatment solution (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at sub-boiling (between 95°C-99°C) temperatures for 10 minutes to unmask the DNA, and then transferred to deionized water and washed twice. Pre-warmed slides were treated for 10 minutes in protease solution (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA,USA) to allow for target accessibility at 40°C, and washed twice with PBS. Slides were fixed in a 4% formalin solution for 5 minutes and washed in PBS. Slides were then incubated for 3 hours with the appropriate probes (β-actin or peacock herpes) diluted in Hyb A buffer (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA,USA) at 40°C in a humidified Thermobrite slide hybridizer. Slides were washed 4 times in wash buffer, and then incubated for 25 minutes at 40°C in PreAmp1 (preamplifier) diluted in prewarmed Hyb B buffer (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA,USA). Slides were washed 3 times in wash buffer, and then incubated in Amp 1 (amplifer) in prewarmed Hyb B buffer for 15 minutes at 40°C. Slides were again washed 3 times, and incubated in LP-AP (hybridize label probe) in prewarmed Hyb C buffer (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA,USA) for 15 minutes at 40°C. Slides were washed again 3 times in wash buffer and incubated for 10 minutes in AP-Enhancer solution (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA,USA) at room temperature. After decanting the enhancer solution, fast-red substrate (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA,USA) was added to slides and incubated at 40°C for 30 minutes in the dark. After the incubation, the slides were washed in PBS and fixed in 4% formalin for 5 minutes at room temperature. Slides were counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) fluorescent stain (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), mounted, and sealed using nail polish. Sections were viewed using brighfield and fluorescent microscopy (Zeiss Axio fluorescent microscope, Scope AI, equipped with a Jenoptic ProgResC5 CCD camera, or Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescent microscope equipped with a CFI Plan Fluor 100× oil objective, 12V 100W mercury lamp, and DVC 2000C high resolution CCD camera). Images were acquired either using Mac Capture Pro 2.6.0 software (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany) or Stereo Investigator software (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA).

Results

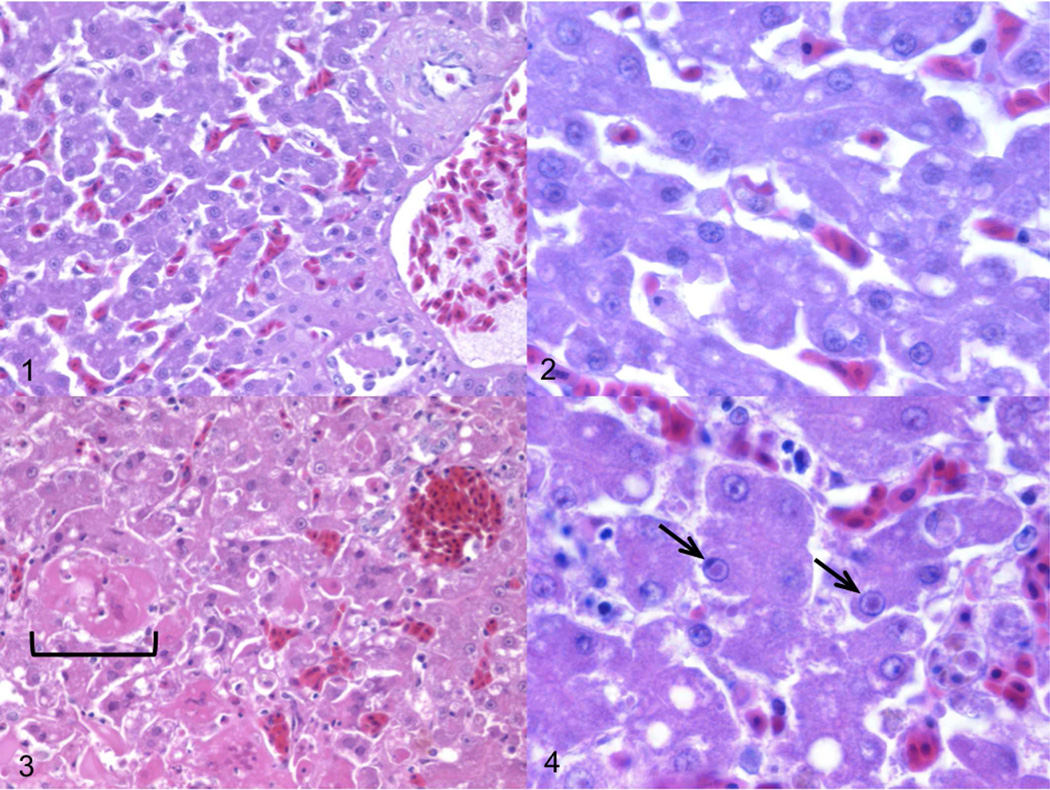

Between 1994 and 2002 twelve pheasants from three species, Polyplectron inopinatum (mountain peacock pheasant), Polyplectron malacense (Malayan peacock pheasant), and Afropavo congensis (Congo peafowl), died acutely with multifocal necrotizing hepatitis with hepatocellular eosinophilic inclusions (Fig. 1–4) and necrotizing splenitis, after presenting briefly with clinical signs of lethargy and anorexia. Necrotizing enteritis with intraepithelial eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions was seen in one of the Malayan peacock pheasant and 3 of the mountain peacock pheasants.

Figures 1-4.

Figure 1. Liver; normal Malayan peacock pheasant case No. 14. HE. Figure 2. Liver; higher magnification of normal bird shown in Figure 1. HE. Figure 3. Liver; diseased Malayan peacock pheasant case No. 11 that was confirmed to be positive for herpesvirus by PCR. Necrotic areas (bracket) are evident in the herpesvirus-infected bird. HE. Figure 4. Higher magnification of cells identified in Figure 3 reveals distinct eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions (arrows). HE.

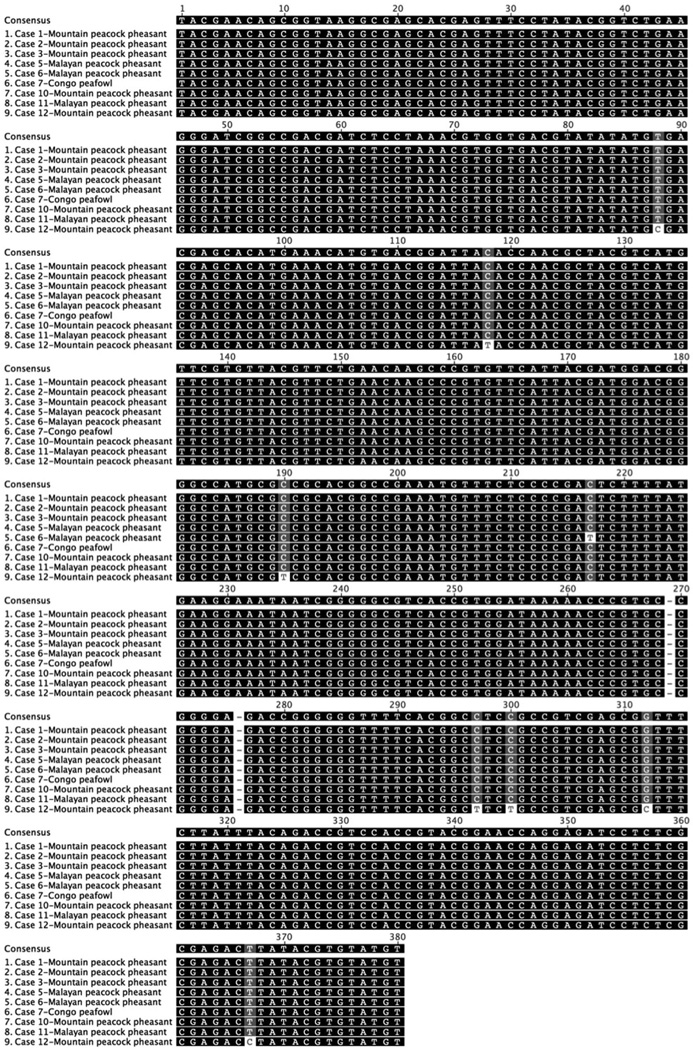

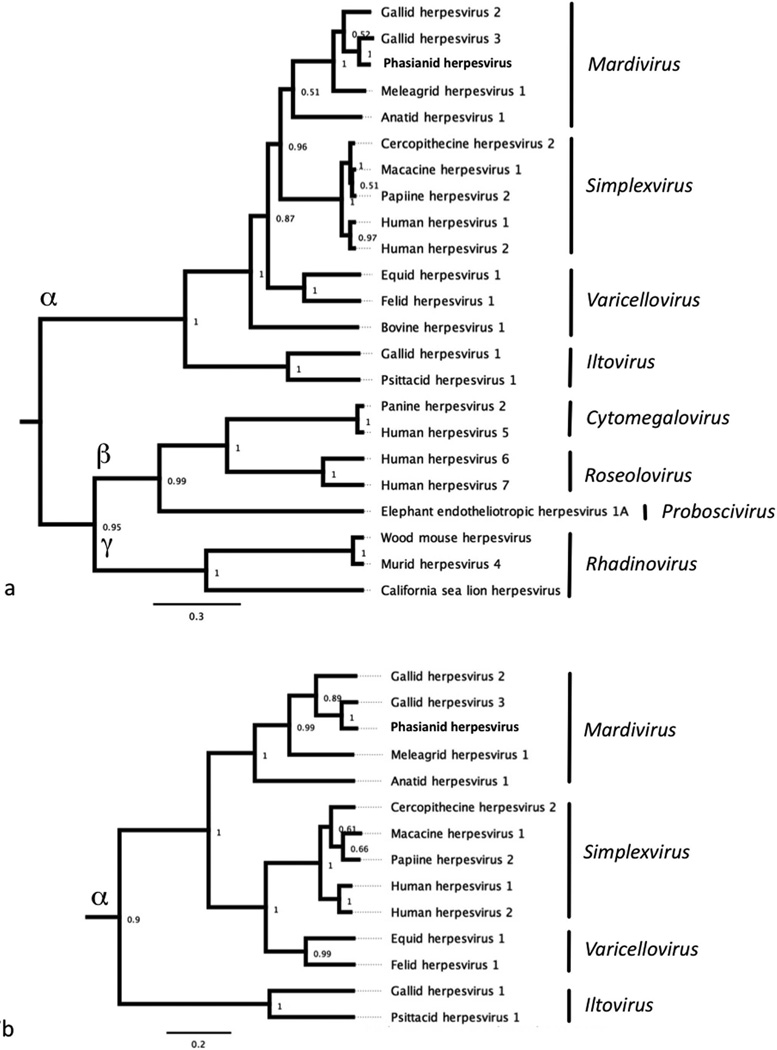

DNA samples were subjected to PCR analysis using degenerate primers specific for the DNA polymerase (UL30) and DNA terminase genes commonly found in all members of Herpesviridae. The nucleotide sequences of these PCR products were determined from 9 out of 12 samples from symptomatic birds (case Nos. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12). In the other three cases only the 220 bp product of the DNA polymerase was successfully amplified (case Nos. 4, 8, and 9). The DNA sequences were translated, and a 162 amino acid sequence of the DNA terminase gene and a 46 amino acid sequence from the DNA polymerase gene were obtained. Viral DNA terminase sequences were nearly identical in all birds indicating infection with the same herpesvirus (Fig. 5). The Malayan peacock pheasant DNA terminase had 92% identity at the nucleotide level with Gallid herpesvirus 3 (GaHV-3) and 77.7% identity with Gallid herpesvirus 2 (GaHV-2, Marek’s disease virus serotype 1) (BLASTn). Protein alignments comparing a translated 164 amino acid sequence of DNA terminase from the Malayan peacock herpesvirus with representative alpha, beta, and gamma herpesviruses sequences obtained from GenBank are shown in Fig. 6 (Genbank accession numbers are indicated). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of the multiple protein alignment was performed and representative sequences clustered into the expected subfamilies for alpha, beta, and gamma herpesviruses. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, the peacock pheasant herpesvirus (Phasianid herpesvirus) belonged to the Mardivirus genus in the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily, and is most closely related to Gallid herpesvirus 3 (GaHV-3) (Fig. 7a). An additional phylogenetic analysis performed on a 46 amino acid multiple protein sequence alignment of DNA polymerase within alphaherpesviruses resulted in a similar phylogenetic tree (Fig. 7b). Pairwise identity for DNA terminase was determined for all species in the protein alignment (Table 1). PAUP distance matrix analysis results show that the Phasianid herpesvirus is 93.8% identical to GaHV-3 and 89.4% identical to GaHV-2, 84.4% identical to Meleagrid herpesvirus (MeHV-1), and 74.4% to Anatid herpesvirus at the amino acid level. Although identity as high as 94% is not seen between other known mardiviruses, this level of identity is seen in other groups of alphaherpesviruses such as simplexviruses in primates (Table 1). For example, Cercopithacine herpesvirus 2 (CeHV-2) shares 95.6% identity with Human herpesviruses 1 and 2 (HHV-1, HHV-2), and Papiine herpesvirus 2 (PaHV-2) shares 94.9% identity with HHV-2.

Figure 5.

Consensus sequence and nucleotide alignment of a 380 bp sequence of herpesvirus of DNA packaging subunit 1 gene (DNA Terminase). Nucleotides indicated in black indicate 100% similarity, dark grey-80–100% similarity in the alignment, light grey-60–80% similarity, and white-less than 60% similarity using an identity score matrix (Geneious Pro™ software).

Figure 7.

a and b. Bayesian phylogenetic tree of a. herpesvirus DNA packaging subunit 1 gene (UL-15, DNA Terminase) and b. the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase amino acid sequences from the Malayan peacock pheasant and representative sequences obtained from GenBank. Sequences were aligned using Geneious Pro™ software. Bayesian posterior probabilities of branching demonstrate the robustness of the individual clades.

Table 1.

Pairwise identity of amino acids between different species of herpesviruses generated from a pairwise distance matrix calculated using PAUP software.

|

Accession Number |

Phasianid herpesvirus |

Gallid herpesvirus 2 |

Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 |

Gallid herpesvirus 1 |

Gallid herpesvirus 3 |

Anatid herpesvirus 1 |

|

| Phasianid herpesvirus | JN127369 | 89.4 | 84.4 | 56.1 | 93.8 | 74.4 | |

| Gallid herpesvirus 2 | AAS01654 | 85.7 | 55.1 | 88.2 | 73.9 | ||

| Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 | NP 073308 | 55.1 | 82.0 | 71.4 | |||

| Gallid herpesvirus 1 | YP 182378 | 55.1 | 56.3 | ||||

| Gallid herpesvirus 3 | NP 066845 | 73.9 | |||||

| Anatid herpesvirus 1 | YP 003084405 | ||||||

|

Wood mouse herpesvirus |

Psittacid herpesvirus 1 |

Murid herpesvirus 4 |

Bovine herpesvirus 1 |

Equid herpesvirus 1 |

Panine herpesvirus 2 |

||

| Phasianid herpesvirus | JN127369 | 37.3 | 58.0 | 36.7 | 65.2 | 76.6 | 46.8 |

| Gallid herpesvirus 2 | AAS01654 | 38.4 | 57.6 | 37.7 | 66.0 | 77.4 | 47.1 |

| Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 | NP 073308 | 38.4 | 57.0 | 37.1 | 64.8 | 74.8 | 43.9 |

| Gallid herpesvirus 1 | YP 182378 | 35.2 | 71.9 | 34.6 | 51.9 | 58.2 | 43.4 |

| Gallid herpesvirus 3 | NP 066845 | 39.0 | 57.6 | 38.4 | 66.0 | 77.4 | 44.6 |

| Anatid herpesvirus 1 | YP 003084405 | 38.4 | 57.6 | 37.7 | 66.7 | 75.5 | 44.6 |

| Wood mouse herpesvirus | ABO48409 | 33.3 | 95.6 | 38.0 | 39.9 | 40.5 | |

| Psittacid herpesvirus 1 | NP 944422 | 34.6 | 57.0 | 58.9 | 38.4 | ||

| Murid herpesvirus 4 | NP 044866 | 38.0 | 39.2 | 41.8 | |||

| Bovine herpesvirus 1 | CAA88116 | 73.0 | 46.5 | ||||

| Equid herpesvirus 1 | YP 053090 | 45.9 | |||||

|

Human herpesvirus 5 |

Human herpesvirus 6 |

Human herpesvirus 7 |

Elephant endo. herpesvirus 1A |

Cercopithecine herpesvirus 2 |

Human herpesvirus 1 |

||

| Phasianid herpesvirus | JN127369 | 47.4 | 46.2 | 45.5 | 44.9 | 73.2 | 74.5 |

| Gallid herpesvirus 2 | AAS01654 | 47.8 | 45.9 | 43.9 | 44.6 | 72.2 | 73.4 |

| Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 | NP 073308 | 45.2 | 43.9 | 44.6 | 44.6 | 70.3 | 71.5 |

| Gallid herpesvirus 1 | YP 182378 | 44.0 | 43.4 | 44.0 | 41.5 | 56.3 | 57.6 |

| Gallid herpesvirus 3 | NP 066845 | 45.2 | 45.9 | 45.2 | 45.2 | 74.1 | 75.3 |

| Anatid herpesvirus 1 | YP 003084405 | 45.9 | 43.9 | 43.3 | 42.7 | 74.1 | 75.3 |

| Wood mouse herpesvirus | AB048409 | 41.1 | 44.9 | 43.7 | 45.6 | 39.9 | 39.2 |

| Psittacid herpesvirus 1 | NP 944422 | 38.4 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 39.0 | 58.2 | 59.5 |

| Murid herpesvirus 4 | NP 044866 | 41.8 | 44.9 | 44.3 | 44.9 | 38.6 | 38.0 |

| Bovine herpesvirus 1 | CAA88116 | 45.9 | 43.9 | 43.9 | 40.1 | 70.3 | 69.6 |

| Equid herpesvirus 1 | YP 053090 | 46.5 | 44.6 | 43.3 | 44.6 | 77.8 | 77.8 |

| Panine herpesvirus 2 | AF480884 80 | 98.1 | 61.0 | 58.5 | 56.6 | 43.9 | 43.9 |

| Human herpesvirus 5 | ACM48067 | 61.6 | 57.9 | 56.6 | 43.9 | 44.6 | |

| Human herpesvirus 6 | NP 042953 | 82.4 | 49.1 | 45.9 | 47.8 | ||

| Human herpesvirus 7 | YP 073802 | 49.1 | 46.5 | 45.9 | |||

| Elephant endo. herpesvirus 1A | ADK70800 | 42.0 | 42.7 | ||||

| Cercopithecine herpesvirus 2 | YP 164457 | 95.6 | |||||

| Human herpesvirus 1 | ACM62237 | ||||||

|

Macacine herpesvirus 1 |

Papiine herpesvirus 2 |

Human herpesvirus 2 |

Felid herpesvirus 1 |

California Sea lion herpesvirus |

|||

| Phasianid herpesvirus | JN127369 | 73.2 | 73.2 | 74.5 | 72.0 | 33.8 | |

| Gallid herpesvirus 2 | AAS01654 | 72.2 | 72.2 | 73.4 | 70.3 | 32.9 | |

| Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 | NP 073308 | 70.3 | 70.3 | 71.5 | 68.4 | 32.9 | |

| Gallid herpesvirus 1 | YP 182378 | 57.0 | 57.0 | 57.6 | 55.7 | 30.4 | |

| Gallid herpesvirus 3 | NP 066845 | 74.1 | 74.1 | 75.3 | 71.5 | 33.6 | |

| Anatid herpesvirus 1 | YP 003084405 | 74.1 | 74.1 | 74.1 | 72.8 | 31.5 | |

| Wood mouse herpesvirus | ABO48409 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 39.2 | 37.3 | 52.4 | |

| Psittacid herpesvirus 1 | NP 944422 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 59.5 | 58.2 | 30.4 | |

| Murid herpesvirus 4 | NP 044866 | 38.6 | 38.6 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 53.1 | |

| Bovine herpesvirus 1 | CAA88116 | 69.6 | 69.6 | 70.3 | 70.3 | 33.6 | |

| Equid herpesvirus 1 | YP 053090 | 77.8 | 77.8 | 77.8 | 81.6 | 32.2 | |

| Panine herpesvirus 2 | AF480884 80 | 43.3 | 43.3 | 44.6 | 45.6 | 40.8 | |

| Human herpesvirus 5 | ACM48067 | 43.9 | 43.9 | 45.2 | 45.9 | 41.5 | |

| Human herpesvirus 6 | YP 042953 | 45.9 | 45.9 | 47.1 | 44.6 | 46.3 | |

| Human herpesvirus 7 | YP 073802 | 46.5 | 46.5 | 46.5 | 44.6 | 46.9 | |

| Elephant endo. herpesvirus 1A | ADK70800 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 42.7 | 43.3 | 42.2 | |

| Cercopithecine herpesvirus 2 | YP 164457 | 99.4 | 98.7 | 95.6 | 74.7 | 34.2 | |

| Human herpesvirus 1 | ACM62237 | 95.6 | 94.9 | 98.7 | 75.3 | 34.9 | |

| Macacine herpesvirus 1 | NP 851874 | 99.4 | 95.6 | 74.7 | 34.2 | ||

| Papiine herpesvirus 2 | YP 443861 | 94.9 | 74.7 | 34.9 | |||

| Human herpesvirus 2 | NP 044484 | 74.7 | 34.9 | ||||

| Felid herpesvirus 1 | ACT88343 | 34.2 | |||||

| California Sea lion herpesvirus | AF236051 1 | ||||||

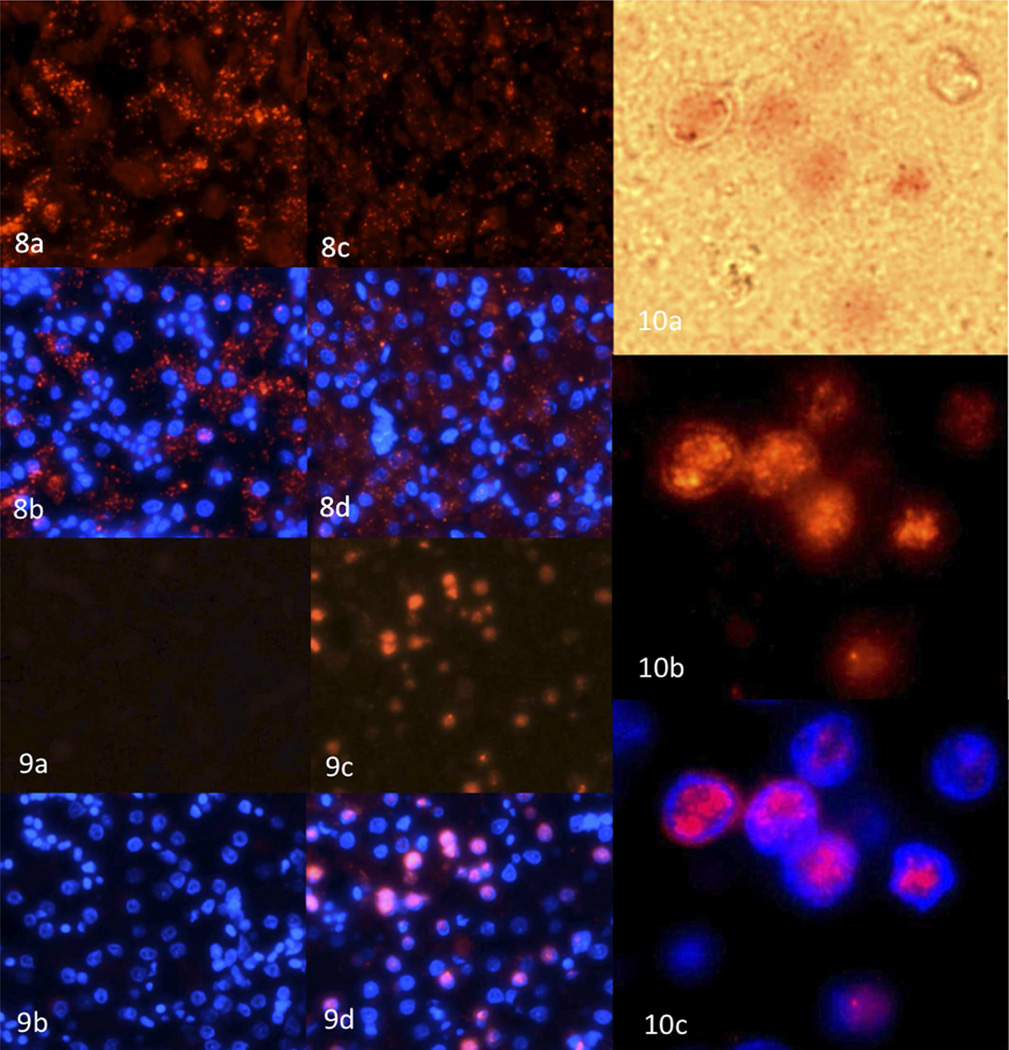

The distribution of the Phasianid herpesvirus nucleic acid in liver sections from Malayan peacocks with and without disease was assessed using branched in situ hybridization (Quantigene View RNA, Panomics), employing probes that hybridize to the mRNA of Malayan peacock pheasant herpesvirus DNA polymerase or a housekeeping gene, β-actin, as a control (Fig. 8–10). Signal for β-actin was observed in Malayan peacock pheasants with or without disease; however the intensity of the hybridization signal was lower in the bird with disease. In contrast, hybridization signal with peacock herpesvirus probes was only detected in the bird with disease. The nuclear distribution of herpesvirus DNA polymerase was determined using DAPI staining.

Figures 8-10.

Figure 8a and b. Liver; in situ hybridization for β-actin fluorescent staining (8a) or β-actin and DAPI co-staining (8b) of normal Malayan peacock pheasant case No. 14. The tissue was counter-stained with DAPI (blue) to identify the nuclei and images were merged to show the localization of β-actin and DNA polymerase relative to the nuclei. Figure 8c and d. Liver, β-actin fluorescent staining (8c) or β-actin and DAPI co-staining (8d) in herpesvirus-infected Malayan peacock pheasant case No. 11. Figure 9a and b. Liver, herpesvirus DNA polymerase fluorescent staining (9a) or DNA polymerase and DAPI co-staining (9b) in normal Malayan peacock pheasant case No. 14. Figure 9c and d. Liver, herpesvirus DNA polymerase fluorescent staining (9c) or DNA polymerase and DAPI co-staining (9d) in infected Malayan peacock pheasant case No. 11. Figure 10. Liver, Higher magnification of case No.11 showing herpesvirus DNA polymerase (pink staining) by brightfield microscopy (10a), DNA polymerase fluorescent staining (10b), or DNA polymerase and DAPI co-staining (10c).

Discussion

Our results support the identification of a novel alphaherpesvirus, tentatively named Phasianid herpesvirus, in the genus Mardivirus. This virus was associated with severe disease and death in three species of pheasants. Chicken inoculation studies of the herpesvirus affecting the exotic pheasants in this zoological collection performed in 1996 produced the same gross and microscopic lesions seen in the naturally-infected pheasants.14 However, at that time, molecular characterization was not performed.14

Phylogenetic and distance matrix analysis indicates that the closest relative to Phasianid herpesvirus is Gallid herpesvirus 3 (GaHV-3), a genetically similar, non-pathogenic virus that is widely used as a vaccine against Marek’s disease.18,19,22 Marek’s disease is a neoplastic lymphoproliferative disease of gallinaceous birds that produces visceral and/or cutaneous lymphoma, immunosuppression, paralysis and/or death.17 The causative agent, GaHV-2, is distributed worldwide, and is associated with severe economic losses in domestic poultry.15,17 The disease has been reported in pheasants, quail, and game fowl.16 GaHV-2 is closely related to but taxonomically distinct from GaHV-3 and MeHV-1.11–13

Live vaccines for Marek’s disease include GaHV-3, MeHV-1, and attenuated GaHV-2. GaHV-3 strains are considered to be widely prevalent in the poultry industry, replicate in the host, and spread easily by contact.4,18,19 However, the long-term effects of live vaccine strains such as MeHV-1 or GaHV-3 in other non-domesticated galliform species, particularly species that are co-housed together in zoological or captive collections and farms, is largely unknown.

Herpesviruses are theorized to have co-evolved with their hosts, and the severity of the lesions observed in the liver and spleen and presence of the disease in three species of pheasants, suggests that interspecies transfer of the virus may have occurred from a yet unidentified host galliform species. Vaccination of birds against Marek's disease has not been performed in the WCS collection since 1985, and none of the pheasants in the WCS collections were housed near vaccinated domestic poultry. In an effort to determine when this herpesvirus entered the collection we retrospectively examined earlier cases of suspected herpesvirus infection and identified histologic hepatic necrosis with intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions consistent with herpesvirus infection in a Temminck's tragopan that died in 1988. PCR analysis revealed DNA polymerase products identical to Phasianid herpesvirus. However, we were unable to amplify DNA terminase gene products.

The mountain peacock pheasant (Polyplectron inopinatum), the Malayan peacock pheasant (Polyplectron malacense), and the Congo peafowl (Afropavo congensis), are all listed as vulnerable to extinction under the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species due to decreasing population trends resulting from increased habitat fragmentation and deforestation, which are compounded by the bird’s restricted range.3 In the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Congo peafowl population is small and scattered and critical habitat is being lost to mining, subsistence agriculture, and logging.3 Population growth is hindered by the long history of political conflict, war, increasing human population pressures, and poaching.3 Maintaining healthy birds in captivity provides a conservation option for each of these species and ensures that viable breeding populations exist in the event that species rescue or recovery efforts are required. Future research aimed at testing the safety and efficacy of vaccination of pheasant species with closely-related non-pathogenic strains of mardiviruses to protect against pathogenic herpesvirus infection, will be beneficial for captive management and as a safeguard for these valuable species.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health NIAID - AI57158 to WIL, NIAID - AI070411 to WIL, and the US Department of Defense DoD - URSFTS Grant No EGG0035165 to WIL. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Tracey McNamara and the support of the Clinical, Pathology, and Ornithology Departments at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

References

- 1.Alfonso CL, Tulman ER, Lu Z, Zsak L, Rock DL, Kutish GF. The Genome of Turkey Herpesvirus. J of Virol. 2001;75:971–978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.971-978.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baines JD. Envelopment of herpes simplex virus nucleocapsids at the inner nuclear membrane. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K, editors. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Chapter 11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butchart S, Garson P, McGowen P. Afropavo congensis, Polyplectron inopinatum, Polyplectron malacense. IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4, ed. International B. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calnek BW, Schat KA, Peckham MC, Fabricant J. Field trials with bivalent vaccine (HVT and SB-1) against Marek's disease. Avian diseases. 1983;27:844–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chmielewicz B, Goltz M, Ehlers B. Detection and multigenic characterization of a novel gammaherpesvirus in goats. Virus Res. 2001;75:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(00)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison A. Evolution of the herpesviruses. Vet Micro. 2002;86:69–88. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(01)00492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison A, Eberle R, Ehlers B, et al. The order Herpevirales. Arch Virol. 2009;154:171–177. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0278-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA. Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunther BM, Klupp BG, Gravendyck M, Lohr JE, Mettenleiter TC, Kaleta EF. Comparison of the genomes of 15 avian herpes-virus isolates by restriction endonuclease analysis. Avian Path. 1997;26:305–316. doi: 10.1080/03079459708419213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huelsenbeck JPFR. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes A, Rivailler P. Phylogeny and recombination history of gallid herpesvirus 2 (Marek's disease virus) genomes. Virus Res. 2007;130:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGeoch DJ, Dolan A, Ralph AC. Toward a comprehensive phylogeny for mammalian and avian herpesvirus. J of Virol. 2000;74:10401–10406. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10401-10406.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGeoch DJ, Rixon FJ, Davison AJ. Topics in herpesvirus genomics and evolution. Virus Res. 2006;117:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNamara TS, Lucio-Martinez B, Factor SM, Kress Y. Investigation of a herpesviral infection in three species of pheasants. Proc Annu Conf Am Assoc Zoo Vet. 1996;169 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrow C, Fehler F. Marek's disease a worldwide problem. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair V. Evolution of Marek's disease- a paradigm for incessant race between the pathogen and the host. Vet J. 2005;170:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osterrieder N, Kamil J, Schumacher D, Tischer B, Trapp S. Marek’s disease virus: from miasma to model. Nature Rev Micro. 2006;4:283–294. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petherbridge L, Xu H, Zhao Y, et al. Cloning of Gallid herpesvirus 3 (Marek’s disease virus serotype-2) genome as infectious bacterial artificial chromosomes for analysis of viral gene functions. J Virol Methods. 2009;158:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schat K, Calnek B. Characterization of an apparently non-oncogenic Marek's disease virus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1978;60:1075–1082. doi: 10.1093/jnci/60.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thureen DR, Keeler JCL. Psittacid Herpesvirus 1 and Infectious Laryngotracheitis Virus: Comparative Genome Sequence Analysis of Two Avian Alphaherpesviruses. J of Virol. 2006;80:7863–7872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00134-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.VanDevanter D, Warrener P, Bennett L, et al. Detection and analysis of diverse herpesviral species by consensus primer PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1666–1671. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1666-1671.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witter R. Protective efficiency of Marek's disease vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;255:57–90. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56863-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]