Abstract

Purpose

Despite sincere commitment to egalitarian, meritocratic principles, subtle gender bias persists, constraining women’s opportunities for academic advancement. The authors implemented a pair-matched, single-blind, cluster-randomized, controlled study of a gender bias habit-changing intervention at a large public university.

Method

Participants were faculty in 92 departments or divisions at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Between September 2010 and March 2012, experimental departments were offered a gender bias habit-changing intervention as a 2.5 hour workshop. Surveys measured gender bias awareness; motivation, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations to reduce bias; and gender equity action. A timed word categorization task measured implicit gender/leadership bias. Faculty completed a worklife survey before and after all experimental departments received the intervention. Control departments were offered workshops after data were collected.

Results

Linear mixed-effects models showed significantly greater changes post-intervention for faculty in experimental vs. control departments on several outcome measures, including self-efficacy to engage in gender equity promoting behaviors (P = .013). When ≥ 25% of a department’s faculty attended the workshop (26 of 46 departments), significant increases in self-reported action to promote gender equity occurred at 3 months (P = .007). Post-intervention, faculty in experimental departments expressed greater perceptions of fit (P = .024), valuing of their research (P = .019), and comfort in raising personal and professional conflicts (P = .025).

Conclusions

An intervention that facilitates intentional behavioral change can help faculty break the gender bias habit and change department climate in ways that should support the career advancement of women in academic medicine, science, and engineering.

Nearly two decades ago Fried and colleagues conducted one of the first series of interventions aimed at promoting gender equity in academic medicine.1 Interventions were structural (e.g., changing the time of department meetings) and benefited both men and women. In the nearly two decades since publication of this study, it has become clear that addressing structural issues alone, while important, is insufficient if we are to achieve gender equity in academic medicine, science, and engineering.2–4 Recognizing the complexities of professional development for women in academic medicine, Magrane and colleagues put forth a multi-faceted conceptual model that situates women faculty members as agents within several interdependent, complex adaptive systems that include organizational influences, individual decisions, societal expectations and gender bias.5 Westring and colleagues found in a comprehensive, multi-level assessment that four distinct but related dimensions contributed to a work environment conducive to women’s academic success: equal access, work-life balance, supportive leadership, and freedom from gender bias.4

Reports from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the National Academies of Science conclude that gender bias operates in personal interactions, evaluative processes, and departmental cultures to subtly yet systematically impede women’s career advancement in academic medicine, science, and engineering.6–8 Experimental research confirms that this persistent gender bias is rooted in culturally ingrained gender stereotypes that depict women as less competent than men in historically male-dominated fields such as medicine, science, and engineering—particularly in leadership positions.6–11 Despite significant reductions in explicitly endorsed stereotype-based gender bias and adoption of anti-discriminatory policies over the past half century, subtle forms of gender bias that may be inadvertent and unintentional persist.6–12

Introduction

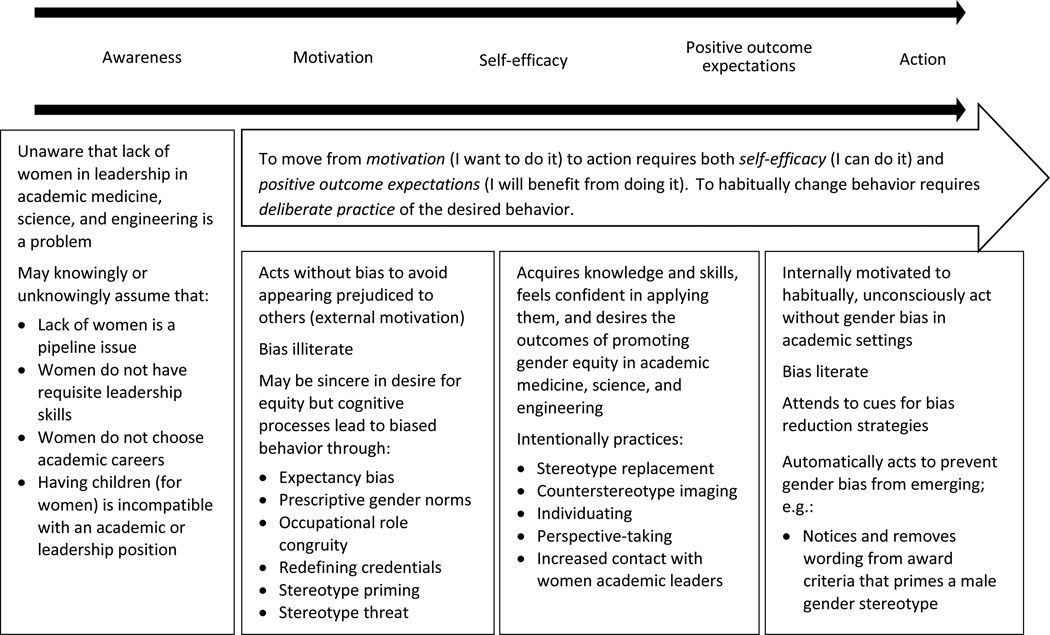

There is growing evidence that stereotype-based bias functions like a habit as an ingrained pattern of thoughts and behaviors.13–15 Changing a habit is a multistep process. Successful habit-changing interventions not only increase awareness of problematic behavior but must motivate individuals to learn and deliberately practice new behaviors until they become habitual.16 Much research in this area emanates from studies of health behavior change.17 In the only study to approach unintentional race bias as a habit, Devine and colleagues were able to reduce automatic negative assumptions about Blacks by undergraduate students who were randomly assigned to practice stereotype-reducing cognitive strategies compared with students in a control group.13 Building on that work, we approached gender bias by faculty in academic medicine, science, and engineering as a remediable habit. We hypothesized that strategies employed to help individuals break other unwanted habits would assist faculty in breaking the gender bias habit (Figure 1)13,14,16,18 and positively influence department climate.15,19–23

Figure 1.

Conceptual model underpinning a study of 46 experimental and 46 control departments, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2010–2012. Multistep process for reducing faculty’s gender bias habit in academic medicine, science, and engineering.

Method

Design overview

We conducted a pair-matched, single-blind, cluster randomized, controlled study at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) comparing a gender bias habit-reducing intervention delivered separately to 46 departments with 46 control departments. The control departments were offered the intervention after its effects were assessed in the experimental departments (“wait-list controls”).24 Participants were faculty in these 92 medicine, science, or engineering departments. They were surveyed within 2 days pre-intervention and at 3 days and again at 3 months post-intervention. Participants were unaware of allocation status. The investigating team was blinded to department assignment until random allocation was complete. The UW-Madison institutional review board approved this study. Participants gave informed consent for each survey and at each workshop intervention.

Setting and participants

Eligibility

Eligible departments resided in the 6 schools/colleges that house most medicine, science, and engineering faculty at UW-Madison. We excluded the School of Nursing because it had no comparable unit for matching. Three large departments were separated into their existing divisions which function administratively like departments (e.g., subspecialties in the Department of Medicine). These divisions were thereafter designated “departments.” Two small subspecialties, formerly part of a larger department, were returned to the “base” department; 2 departments that cross 2 schools but have a single chair were merged; and one small basic science department was merged with a closely-related basic science department in the same college. Two departments were excluded: one was used as a pilot to test measures and provide feedback during workshop development and one because the department chair was a study investigator. A total of 2,290 faculty in 92 departments participated in the study.

Recruitment

During the 12-month period beginning September 2009, a study investigator (M.C. or J.S.) attended a regularly-scheduled department meeting to describe the study. One of the 92 departments declined this visit and its members received only a handout. Attendees were told that their department would be invited to participate in a workshop sometime over the next 2–3 years, and that they would receive an online survey before and twice after their department’s workshop. Because control departments would receive questionnaires unattached to a workshop, we stated that we would send a series of the online surveys at some point over the course of the study “to assess the reliability of our measures.” Department visits occurred before random allocation so neither investigators nor participating faculty were aware of allocation status at these visits.25 Faculty were unaware that any randomization would occur.26

Pair matching

We assigned each department 1 of 4 broad disciplinary codes: biological, physical, or social science; or arts and humanities. We paired departments based on disciplinary category, school/college, and size to ensure balanced treatment allocation and distribution of characteristics that might affect outcome measures.27,28 After independently creating department matches for these factors, 4 of the study investigators met to attain consensus (L.B., M.C., E.F., J.S.) Because faculty gender and rank could not be evenly matched in control and experimental departments, those variables were included as covariates in data analysis.

Randomization and intervention

The departments within each pair were randomly allocated to experimental or control status using a random number generator. No deviations from random assignment occurred.25 All experimental departments were offered the workshop between September 2010 and March 2012; control departments were offered workshops 12–18 months after completion of data collection. One investigator (M.C.) delivered all or part of a standardized workshop format14 to each experimental department; a second investigator (P.D. or J.S.) co-presented at 41 workshops.29 The intervention, a 2.5 hour interactive workshop, occurred at the department level to enhance participation, avoid group contamination,30 and capitalize on existing organizational networks.19,20 Incorporating principles of adult education31,32 and intentional behavioral change,16,18 we designed the workshop to first increase faculty’s awareness of gender bias in academic medicine, science, and engineering; and then to promote motivation, self-efficacy, and positive outcome expectations for habitually acting in ways consistent with gender equity (Figure 1).14 The workshop began by making the case for the importance of utilizing all available talent to advance science, improve the nation’s health, and promote economic vitality. We reviewed research on the pervasiveness of stereotype-based gender bias in decision-making and judgment and its detrimental effect on these goals. Participants then identified how gender equity could enhance their own department or field. Three modules followed this introduction. The first reviewed research on the origins of bias as a habit.12,14 The second promoted “bias literacy”33 by describing and labeling 6 manifestations of stereotype-based gender bias relevant to academic settings:

expectancy bias (i.e., how group stereotypes lead to expectations about individual members of that group)34;

prescriptive gender norms (i.e., cultural assumptions about how men and women should and should not behave and the social penalties of violating these norms)35;

occupational role congruity (i.e., the subtle advantage accrued to men being evaluated for roles that require traits more strongly linked to male stereotypes such as scientist and leader)36;

redefining credentials (i.e., how the same credential can be valued differently depending on who has it)37;

stereotype priming (i.e., ways in which even subtle reminders of male or female gender stereotypes bias one’s subsequent judgment of an individual man or woman38,39; and

stereotype threat (i.e., how fear of confirming a group’s negative performance stereotype can lead a member of that group to underperform, such as girls in math or women in leadership).40

The third module promoted self-efficacy for overcoming gender bias by providing 5 evidence-based behavioral strategies to practice:13,14

stereotype replacement (e.g. if girls are being portrayed as bad at math, identify this as a gender stereotype and consciously replace it with accurate information)13;

positive counterstereotype imaging (e.g., before evaluating job applicants for a position traditionally held by men, imagine in detail an effective woman leader or scientist )41;

perspective taking (e.g., imagine in detail what it is like to be a person in a stereotyped group)42;

individuation (e.g., gather specific information about a student, patient, or applicant to prevent group stereotypes from leading to potentially inaccurate assumptions43; and

increasing opportunities for contact with counterstereotypic exemplars (e.g., meet with senior women faculty to discuss their ideas and vision).34

We also presented two counterproductive strategies: stereotype suppression (i.e., attempting to be “gender blind”)44 and a strong belief in one’s ability to make objective judgments.45 Both of these have been shown to enhance the influence of stereotype-based bias on judgment. To facilitate behavioral change, participants immediately applied content through paired discussions, audience response, case studies conducted as readers’ theater, and a written commitment to action.31,46–48 As reminders to practice bias-reducing behaviors, participants received a folder containing workshop materials, a bibliography, and a bookmark listing the 6 forms of bias discussed and the 5 bias habit-changing strategies.

Outcomes and follow-up

We evaluated the impact of the workshop with 13 primary outcome measures (Table 1):

Table 1.

Category and Description of Outcome Variables Compared Between 46 Departments Randomly Allocated to Receive a Gender Bias Habit-Reducing Workshop and 46 Control Departments, University of Wisconsin-Madison, September 2010–March 2012

| Category | Outcome variable | Descriptiona |

|---|---|---|

| Implicit bias | Gender and leadership IAT | Assesses the strength of automatic association for stereotypical gender-congruent vs. incongruent leader/supporter assumptions |

| Awareness | IAT concern | Personal concern about one’s IAT performance |

| Bias vulnerability | Perceived vulnerability to unintentional gender bias | |

| Personal bias awareness | Awareness of one’s own subtle gender bias | |

| Environmental bias awareness | Awareness of subtle gender bias in one’s environment | |

| Societal benefit | Perceived benefit to society for promoting gender equity, 3 questions (α = 0.8) | |

| Disciplinary bias | Awareness of gender bias in one’s discipline, 2 questions (α = 0.8) | |

| Motivation | Internal motivation | Motivation to promote gender equity based on one’s internal beliefs |

| External motivation | Motivation to promote gender equity based on concerns of appearing biased to others | |

| Self-efficacy | Gender equity self-efficacy | Confidence in being able to enact gender equity, 5 questions (α = 0.7) |

| Outcome expectations | Negative outcome | Feeling it would be personally risky to promote gender equity in one’s department, 5 questions (α = 0.8) |

| Positive outcome | Feeling it would be personally beneficial to promote gender equity in one’s department, 5 questions (α =0.8) | |

| Action | Action | Acting on a regular basis to promote gender equity in one’s department, 5 questions (α = 0.8) |

Abbreviation: IAT indicates Implicit Association Test.

α= Cronbach’s alpha, used to calculate reliabilities for multiple-item scales.

Implicit gender bias

To measure implicit bias, we used a version of the Implicit Association Test (IAT) that assessed the strength of associating male and female names with leader or supporter words.49

Awareness of gender bias

We developed a 9-item survey based on existing research on gender equity and discussions with women faculty.50 Exploratory factor analysis led us to average responses to questions that assessed perceived benefit to society (societal benefit, 3 questions) and awareness of gender bias in one’s discipline (disciplinary bias, 2 questions), and retain single item questions for personal concern about one’s performance on the IAT (IAT concern), perceived vulnerability to unintentional gender bias (bias vulnerability), awareness of one’s own subtle gender bias (personal bias awareness), and awareness of gender bias in one’s environment (environmental bias awareness).

Motivation to promote gender equity

Plant and Devine’s research distinguishes between motivation that stems from internal sources (i.e., beliefs, values) and motivation that stems from external sources (i.e., the desire to appear nonbiased to others).51 We assessed each of these dimensions with a single question (internal motivation and external motivation).

Self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and action

We derived question content for these measures from existing research on gender equity, academic leadership, and social cognitive theory;7,16,36,52,53 and themes that emerged from 2 focus groups with faculty and senior staff (4 men and 4 women in total). We conceived of willingness to promote gender equity as dependent on individuals’ beliefs in their ability to do so (i.e., their self-efficacy for enacting gender equity) and their perceptions of the cost-benefit ratio of doing so (i.e., their outcome expectations).16 We developed questions to assess gender equity self-efficacy (5 questions) and expectations of both benefits (gender equity positive outcome, 5 questions) and risks (gender equity negative outcome, 5 questions) of acting to promote gender equity. The risk responses were reverse-scored. We also developed 5 questions that asked faculty whether they performed specific gender equity promoting actions on a regular basis (action). The responses to questions assessing each measure were averaged.

Two days before (baseline), 3 days after, and again 3 months after a scheduled workshop, faculty in experimental and control department pairs received an e-mail invitation to take an online survey assessing the 13 primary outcome measures. For the IAT we used response times to compute D-scores where higher numbers indicate a stronger association of male names with leader roles and female names with supporter roles than the reverse.49,54 The other measures used 7-point Likert scales with higher numbers associated with greater movement toward behavioral change. Outcomes were collected and analyzed at the individual level. We hypothesized that post-intervention, faculty in experimental vs. control departments would demonstrate less association of male with leader and female with supporter on the IAT, show greater changes in proximal requisites of bias habit reduction (awareness, internal and external motivation, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations), and report engaging in more action to achieve academic gender equity.

To evaluate the impact of the intervention on department climate, we analyzed 5 questions from the Study of Faculty Worklife.55 This instrument measures faculty’s perception of and satisfaction with the climate within their departments or units, as well as the overall institutional climate.55 This survey was mailed to all faculty prior to and after the workshop was developed and implemented. In the 92 study departments, the survey was sent to 2,495 faculty in 2010, and 2,460 in 2012. (The participant numbers vary from the 2,290 in our study because they were retrieved from a different administrative database.) Questions used 5-point Likert scales and queried the extent to which, within their own departments, respondents felt isolated, felt they “fit in,” felt their colleagues solicited their opinions on work-related matters, felt their colleagues valued their research and scholarship, and felt comfortable raising personal/family responsibilities when scheduling department obligations. We hypothesized that if the intervention led faculty to break the gender bias habit, this would translate into broader changes in department culture leading faculty in experimental departments to respond more positively to questions about department climate.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis with all randomized departments. We used linear mixed-effects models with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to compare responses from faculty in experimental vs. control departments to the 13 primary outcome measures at each time point.56,57 The mean difference between experimental and control departments at follow-up times, minus the baseline difference, indicated the treatment effect. All models were adjusted for gender and rank. Models included 3 random effects to address clustering: person IDs accounted for the repeated measures; department pair IDs accounted for variability between matched pairs; and the interaction between department allocation and department pair IDs accounted for treatment effect variability between matched pairs.58–61 We used likelihood ratio tests (LRT) to obtain P values62 and considered P values less than .05 to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R’s lme4 package with residual maximum likelihood (REML) estimation.62

Dose-response analysis for action

We segregated action results from experimental department faculty and modeled the impact of the percentage of faculty (in quartiles) that attended the workshop (0–14% vs. 14–24% vs. 25–42% vs. 42–91%). This model designated person IDs and department IDs as random effects.

Analysis of department climate questions

We used baseline-adjusted linear mixed-effects models to analyze the department climate questions.57 Post-intervention scores were corrected for pre-scores and analyzed based on department allocation, gender, rank, and the two-way interaction effect between department allocation and gender. Models designated department pair IDs and the interaction between department allocation and department pair IDs as random effects.58–60

Results

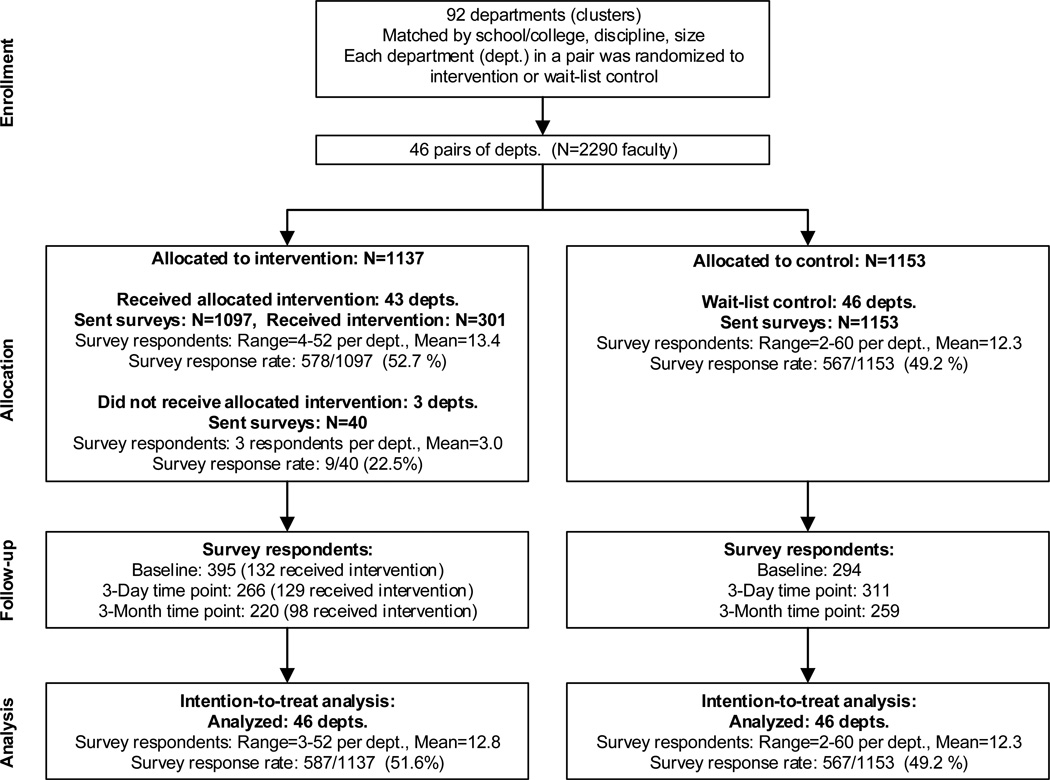

Figure 2 presents the CONSORT flow diagram.63 Of the 46 experimental departments, 43 received the intervention because none of the invited faculty in 3 departments attended their scheduled workshop. Data from these 3 departments were retained in the analyses. No department was lost to follow-up. Workshop attendance varied from 0 (in 3 departments with 8, 17, and 15 members) to 90% (19 of 21 members) of a department’s faculty (mean = 31%, SD = 21). Of the 1,137 faculty invited to a workshop, 301 attended (26%). The chair (or division head) from 72% of departments (33/46) attended their scheduled workshop. Overall, 52% of faculty in experimental departments [587/1,137 (578/1,097 from 43 departments whose faculty attended plus 9/40 from the 3 departments with no attendance)] and 49% of faculty in control departments (567/1,153) responded to the online surveys at least once (Table 2). Response rates within matching categories were similar across experimental and control departments. Full professors were slightly over represented among respondents in experimental departments where 494 respondents reported rank [152 (31%) assistant, 122 (25%) associate, and 220 (45%) full professor] and control departments where 471 respondents reported rank [134 (28%) assistant, 120 (25%) associate, and 217 (46%) full professor] compared with all departments [(N=2,290), 797 (35%) assistant, 546 (24%) associate, and 947 (41%) full professor]. Women also had higher representation among respondents in the experimental departments (204/603, 34%) and control departments (180/571, 32%) than all departments (695/2,290, 30%).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of faculty gender bias-reduction intervention depicting enrollment, department allocation and intervention, and survey response rates, from a study of 46 experimental and 46 control departments, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2010–2012. Information presented is in accordance with flow diagram requirements of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement extended to cluster randomized trials.

Table 2.

Description of Faculty in 46 Control Departments and 46 Experimental Departments who Responded at Least Once to a Survey Sent Before, 3 Days After, and 3 Months After Experimental Departments Received a Gender Bias Habit-Reducing Workshop, University of Wisconsin-Madison, September 2010–March 2012

| Experimental group |

Control group |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No.(%) survey respondents |

No.(%) indicated workshop attendance |

No. (%) survey respondents |

|

| Characteristic | (n =587) | (n =170) | (n =567) |

| School/college | |||

| School of Medicine and Public Health | 328 (55.9) | 106 (62.4) | 293 (51.7) |

| Letters and Science | 102 (17.4) | 23 (13.5) | 110 (19.4) |

| Agricultural and Life Sciences | 72 (12.3) | 13 (7.6) | 83 (14.6) |

| Engineering | 43 (7.3) | 17 (10.0) | 39 (6.9) |

| Veterinary Medicine | 29 (4.9) | 10 (5.9) | 22 (3.9) |

| Pharmacy | 13 (2.2) | 1 (0.6) | 20 (3.5) |

| Department size (number of faculty) | |||

| Large (24+) | 360 (61.3) | 106 (62.4) | 315 (55.6) |

| Medium (14–23) | 159 (27.1) | 41 (24.1) | 177 (31.2) |

| Small (≤13) | 68 (11.6) | 23 (13.5) | 75 (13.2) |

| Broad disciplinary area | |||

| Biological sciences | 424 (72.2) | 130 (76.5) | 369 (65.1) |

| Physical sciences | 100 (17.0) | 29 (17.1) | 96 (16.9) |

| Social sciences | 47 (8.0) | 9 (5.3) | 93 (16.4) |

| Arts and humanities | 16 (2.7) | 2 (1.2) | 9 (1.6) |

| %Femalea | |||

| High | 177 (30.2) | 56 (32.9) | 192 (33.9) |

| Medium | 239 (40.7) | 64 (37.6) | 154 (27.2) |

| Low | 171 (29.1) | 50 (29.4) | 221 (39.0) |

| %Junior faculty | |||

| High (> 40%) | 240 (40.9) | 73 (42.9) | 215 (37.9) |

| Medium (20%–39.9%) | 264 (45.0) | 72 (42.4) | 190 (33.5) |

| Low (< 20%) | 83 (14.1) | 25 (14.7) | 162 (28.6) |

| %Clinical faculty | |||

| No clinical faculty | 239 (40.7) | 60 (35.3) | 269 (47.4) |

| High (> 75.0%) | 198 (33.7) | 60 (35.3) | 175 (30.9) |

| Medium (50%–74.9%) | 101 (17.2) | 33 (19.4) | 90 (15.9) |

| Low (< 50%) | 49 (8.3) | 17 (10.0) | 33 (5.8) |

Value is set differently for physical sciences versus other divisions:low: <10% for physical sciences, <25% for other divisions; medium: 10%–19.99% for physical sciences, 25%–39.99% for others; high: ≥ 20% for physical sciences, ≥ 40% for others.

Baseline responses from faculty in experimental vs. control departments were not significantly different on any of the 13 primary outcome measures. At 3 days post-intervention, faculty in experimental departments showed significantly greater increases in personal bias awareness (P = .009), internal motivation (P = .028), gender equity self-efficacy (P = .026), and gender equity positive outcome (P = .039), (Table 3). At 3 months post-intervention, differences persisted in personal bias awareness (P = .001) and gender equity self-efficacy (P = .013), with experimental department faculty also showing an increase in external motivation (P = .026). Baseline IAT scores showed 66% (377/569) of faculty [68% male (224/330) and 64% female respondents (153/239)] with a slight, moderate, or strong automatic association of male with leader and female with supporter; 21% (122/569) showed no preference and 12% (70/569) showed stronger female leader bias. IAT scores did not change significantly. There were no differences in action. However, when at least 25% of a department’s faculty attended the workshop (26 of 46 experimental departments) we found a significant increase in action at 3 months [25–42% attendance, P = .007; 42–91% attendance, P = .006]. Department chair/head attendance had no effect on any outcome measure.

Table 3.

Mean Difference for Outcome Variables at 3 days and 3 Months, Minus the Baseline Difference, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for 46 Experimental and 46 Control Departments Following a Gender Bias Habit-Reducing Intervention, University of Wisconsin-Madison, September 2010–March 2012a

| Outcome variable | 3-Day | 95 % CI | P value | 3-Month | 95 % CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAT | 0.04 | −0.05 – 0.13 | .412 | 0.01 | −0.09 – 0.11 | .855 |

| Awareness | ||||||

| IAT concern | 0.12 | −0.18 – 0.43 | .435 | 0.10 | −0.22 – 0.43 | .542 |

| Bias vulnerability | 0.21 | −0.02 – 0.43 | .076 | 0.16 | −0.08 – 0.40 | .193 |

| Personal bias | 0.36 | 0.09 – 0.63 | .009b | 0.48 | 0.19 – 0.77 | .001b |

| Environmental bias | 0.08 | −0.15 – 0.32 | .486 | 0.20 | −0.05 – 0.45 | .111 |

| Societal benefit | 0.03 | −0.13 – 0.18 | .732 | 0.06 | −0.10 – 0.23 | .456 |

| Disciplinary bias | 0.02 | −0.22 – 0.25 | .897 | 0.11 | −0.14 – 0.35 | .395 |

| Motivation | ||||||

| Internal | 0.29 | 0.03 – 0.55 | .028b | 0.27 | 0.00 – 0.55 | .052 |

| External | 0.08 | −0.33 – 0.48 | .715 | 0.49 | 0.06 – 0.91 | .026b |

| GE self-efficacy | 0.17 | 0.02 – 0.31 | .026b | 0.20 | 0.04 – 0.35 | .013b |

| GE outcome expectations | ||||||

| Negative | −0.08 | −0.28 – 0.12 | .440 | −0.04 | −0.25 – 0.16 | .678 |

| Positive | 0.17 | 0.01 – 0.32 | .039b | 0.10 | −0.06 – 0.27 | .221 |

| Action | −0.06 | −0.26 – 0.15 | .602 | 0.13 | −0.09 – 0.35 | .251c |

Abbreviations: IAT indicates Implicit Association Test; GE, gender equity.

All models were adjusted for gender and rank.

P<.05.

P<.05 for action at 3 months for the 26 (out of 46) experimental departments with at least 25% workshop attendance when comparing only experimental departments.

Similar percentages of faculty in the experimental or control departments responded to the Study of Faculty Worklife survey, in both 2010 and 2012. In 2010, 48% of faculty responded overall (545/1,144 from experimental departments and 652/1,351 from control departments), and in 2012, 43% of faculty responded (470/1,145 from experimental departments and 590/1,315 from control departments.) Some subgroups of faculty tended to respond more frequently to the survey in both waves. Women respond at higher rates than men; 62% (552/893) of women responded in either 2010 or 2012 and 53% (1,024/1,921) of men responded to at least one wave. Full professors respond more than assistant or associate professors; 61% (691/1,126) of full professors responded in at least one wave, while 52% (885/1,688) of faculty at lower ranks responded in either 2010 or 2012.

There were no significant baseline differences between experimental and control faculty’s responses to any department climate question. Model estimates of the treatment effect showed reduced standard errors after baseline adjustment.64 Post-intervention, faculty in experimental departments felt they “fit in” better (P = .024); that their colleagues valued their research and scholarship more (P = .019); and that they were more comfortable raising personal and family responsibilities in scheduling department obligations (P = .025) (Table 4). Results were consistent across male and female faculty, and workshop attendance by the department chair/head had no impact.

Table 4.

Baseline Adjusted Differences in Responses to Questions About Department Climate From 671 Faculty: 375 Respondents from 46 Departments That Received a Gender Bias Habit-Reducing Intervention and 296 Respondents From 46 Control Departments, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2010–2012

| Climate questions | Difference in response |

SE | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation in department | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.21 – 0.09 | .42 |

| Department fit | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.02 – 0.29 | .024a |

| Colleagues seek opinion | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.04 – 0.26 | .14 |

| Respect for scholarship | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.03 – 0.30 | .019a |

| Raising personal obligations | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.03 – 0.37 | .025a |

P<.05.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized, controlled study of a theoretically-informed intervention to change faculty behavior and improve department climate in ways that would be predicted to promote gender equity and foster women’s academic career advancement. Faculty in departments exposed to the gender bias habit-reducing intervention demonstrated immediate boosts in several proximal requisites of intentional behavioral change: personal awareness, internal motivation, perception of benefits, and self-efficacy to engage in gender equity-promoting behaviors. The sustained increase in self-efficacy beliefs at 3 months provides strong evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention.52 Self-efficacy is the cornerstone of widely accepted behavioral change theories.16,18,52 Positive outcome expectations are also important in promoting behavioral change16 and increased at 3 days after the intervention. When at least 25% of a department’s faculty attended the workshop, self-reports of actions to promote gender equity increased significantly at 3 months. This finding is consistent with research on critical mass,65 the importance of psychological safety in organizational change,66 and the collective dynamics of behavioral change in social networks.67 The increase in external motivation at 3 months supports a change in departmental norms for gender equity-promoting behaviors.

A number of educational offerings have focused on increasing awareness of stereotype-based bias, particularly when it operates unintentionally and unwittingly.68,69 Our findings suggest that only to the extent that these initiatives can increase awareness of personal bias might they help promote behavioral change. In contrast to other educational offerings on stereotype-based bias,68,69 our workshop promoted self-efficacy beliefs by providing participants with specific behaviors to deliberately practice.70 They were asked to envision and write down specifically how they would enact these behaviors in the context of their own personal and professional lives. Similar written commitments to action have been found to promote behavioral change in other settings.47

We are the first to administer the gender/leadership IAT to faculty, and our findings indicated that the majority of male and female faculty have at least a slight bias linking male with leadership and female with supporter. Although faculty may be unaware of this implicit bias, a large body of research predicts that such bias will subtly advantage men and disadvantage women being evaluated as leaders or for leadership opportunities.36,40,71,72 Although the IAT score decreased for faculty in experimental departments, there was no significant difference compared with control departments. Our findings suggest that gender bias habit-reduction can occur and department climate can be improved even in the face of persistent implicit gender/leadership bias as measured with an IAT.

Institutional transformation requires changes at multiple levels, yet it is the individuals within an institution who drive change.19,20,73 Consistent with these tenets of institutional change, we found that an intervention that helped individual faculty members change their gender bias habits led to positive changes in perception of department climate: increased perceptions of fit, valuing of research, and comfort in raising personal and professional conflicts. As with Fried and colleagues’ structural interventions to promote gender equity,1 our educational/behavioral intervention appeared to benefit men and women since both male and female faculty in experimental departments perceived improved climate.

This study is limited to a single institution; however, it included faculty from a wide spectrum of medicine, science, and engineering disciplines. At 31%, the average workshop attendance by a department’s faculty was relatively low; however, this attendance rate is realistic for an activity that involves busy faculty and bodes well for the ability of our intervention to translate into practice at other academic institutions. Multiple outcome measures, as in our study, increase the likelihood of a statistically significant finding by chance alone. However, it is unlikely that a test would be significant at both post-intervention time points by chance as with self-efficacy, that all significant differences would be in the predicted direction, and that experimental departments would also show improvements in climate relative to control departments on a separate survey. Because this is the first study to investigate the impact of an intervention to reduce habitual gender bias among faculty, there are no existing data against which to benchmark the “clinical” significance of the observed changes in participants’ pre- to post-treatment scores. The effect size as defined for educational research74 for statistically significant results in our study ranges from 0.11 to 0.32. It is not unusual in psychological, educational, and behavioral research for interventions with such relatively low effect sizes to be considered meaningful.75 As in our study, the outcomes for a number of such studies are measured by self-report. Our small effect size appears to be associated with meaningful impact because our intervention improved department climate including perceptions of worklife flexibility, which have been linked to retaining and promoting women in academic medicine.3,4,76 Another limitation is the possibility of response bias. Full professors and women were slightly overrepresented relative to all departments among respondents. This overrepresentation occurred in both experimental and control departments in the main study and in the worklife survey, reducing the likelihood that response bias accounted for the differences we observed. Overall, approximately half of the participants in both experimental and control departments responded at least once to the online surveys. Among these groups our analytic method helps mitigate response bias because it includes all respondents regardless of their missing data patterns. We also ran two sensitivity analyses: one with the proportion of respondents at each time point and another based on the difference between time points with only respondents that had data at both time points. Both analyses showed little change in the estimated effects, indicating that response bias had little influence on our comparisons between respondents in experimental and control groups.

In summary, this study makes the following new contributions to the field of gender equity in academic medicine, science, and engineering: the majority of male and female faculty had gender stereotype congruent leadership bias (male leader/female supporter), an intervention that approached gender bias as a remediable habit was successful in promoting gender equity behaviors among faculty, and the change in faculty behaviors appeared to improve the department climate for male and female faculty in medicine, science, and engineering departments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tara Becker and Marjorie Rosenberg for their statistical contributions in launching this study and in early analyses of the data.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 GM088477, DP4 GM096822, and R25 GM083252.

Footnotes

Ethical approval: The protocol for this research (SE-2009-0313) was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Previous presentations: Preliminary results were presented at the Causal Factors and Interventions Workshop, Bethesda, Maryland, on November 8, 2012; and to the Advisory Council of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, on January 24, 2013.

Contributor Information

Molly Carnes, director, Center for Women’s Health Research; professor, Departments of Medicine, Psychiatry, and Industrial & Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; and part-time physician, William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Patricia G. Devine, professor and chair, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Linda Baier Manwell, epidemiologist, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI; and National Training Coordinator for Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration Central Office, Washington, DC..

Angela Byars-Winston, associate professor, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Eve Fine, researcher, Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Cecilia E. Ford, professor, Departments of English and Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Patrick Forscher, graduate student, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin..

Carol Isaac, assistant professor, Mercer University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Anna Kaatz, assistant scientist, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Wairimu Magua, postdoctoral fellow, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Mari Palta, professor, Departments of Biostatistics and Population Health Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Jennifer Sheridan, executive and research director, Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

References

- 1.Fried LP, Francomano CA, MacDonald SM, et al. Career development for women in academic medicine: Multiple interventions in a department of medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, Dottolo AL, Krupat E. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: Gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88:1411–1413. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a34952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westring AF, Speck RM, Sammel MD, et al. A culture conducive to women’s academic success: Development of a measure. Acad Med. 2012;87:1622–1631. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826dbfd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magrane D, Helitzer D, Morahan P, et al. Systems of career influences: A conceptual model for evaluating the professional development of women in academic medicine. J Women’s Health. 2012;21:1224–1251. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academy of Sciences National Academy of Engineering Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Beyond Biases and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill C, Corbett C, St. Rose A. Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrice A. Unconscious bias in faculty and leadership recruitment: A literature review. Association of American Medical Colleges Analysis in Brief. 2009;9:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaac C, Lee B, Carnes M. Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84:1440–1446. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6ba00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biernat M. Stereotypes and shifting standards. In: Nelson T, editor. Handbook of Stereotyping and Prejudice. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2009. pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devine PG, Forscher PS, Austin AJ, Cox WTL. Long-term reduction in implicit race prejudice: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carnes M, Devine PG, Isaac C, et al. Promoting institutional change through bias literacy. i. J Divers High Educ. 2012;5:63–77. doi: 10.1037/a0028128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: The stages of change model. J Womens Health. 2005;14:471–475. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ Behav Hum Decision Proc. 1991;50:248–287. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nonaka I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Org Sci. 1994;5:14–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell C, O’Meara K. Faculty agency: Departmental contexts that matter in faculty careers. [Accessed September 12, 2014];Res High Educ. 2013 54 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-013-9303-x. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carr PL, Szalacha L, Barnett R, Caswell C, Inui T. A " ton of feathers": Gender discrimination in academic medical careers and how to manage it. J Womens Health. 2003;12:1009–1018. doi: 10.1089/154099903322643938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Settles IH, Cortina LM, Malley J, Stewart AJ. The climate for women in academic science: The good, the, bad, and the changeable. Psychol Women Q. 2006;30:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomization Trials in Health Research. London: Arnold; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: Hiding who got what. Lancet. 2002;359:696–700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: Defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359:614–618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai K, King G, Nall C. The essential role of pair matching in cluster-randomized experiments, with application to the Mexican Universal Health Insurance evaluation. Stat Sci. 2009;24:29–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivers NM, Halperin IJ, Barnsley J, et al. Allocation techniques for balance at baseline in cluster randomized trials: A methodological review. Trials. 2012;13:120. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Vol. 29. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knox A. Helping Adults Learn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knowles MS. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 2nd ed. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sevo R, Chubin DE. Bias Literacy: A Review of Concepts in Research on Discrimination. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science Center for Advancing Science & Engineering Capacity; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess D, Borgida E. Who women are, who women should be: Descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotyping in sex discrimination. Psychol Public Policy Law. 1999;5:665–692. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109:573. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uhlmann EL, Cohen GL. Constructed criteria: Redefining merit to justify discrimination. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:474–480. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banaji MR, Hardin C, Rothman AJ. Implicit stereotyping in person judgment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:272–281. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carnes M, Geller S, Fine E, Sheridan J, Handelsman J. NIH Director’s Pioneer Awards: Could the selection process be biased against women? J Womens Health. 2005;14:684–691. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgess DJ, Joseph A, van Ryn M, Carnes M. Does stereotype threat affect women in academic medicine? Acad Med. 2012;87:506–512. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318248f718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blair IV, Ma JE, Lenton AP. Imagining stereotypes away: The moderation of implicit stereotypes through mental imagery. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:828–841. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galinsky AD, Moskowitz GB. Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:708. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heilman ME. Information as a deterrent against sex discrimination: The effects of applicant sex and information type on preliminary employment decisions. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1984;33:174–186. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monteith MJ, Sherman JW, Devine PG. Supression as a stereotype control strategy. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 1998;2:63–82. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uhlmann EL, Cohen GL. ‘I think it, therefore it’s true’: Effects of self-perceived objectivity on hiring discrimination. Organ Behav Hum Decision Proc. 2007;104:207–223. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herreid CF. Case study teaching. New Dir Teach Learn. 2011 Winter;128:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overton GK, MacVicar R. Requesting a commitment to change: Conditions that produce behavioral or attitudinal commitment. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28:60–66. doi: 10.1002/chp.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheridan JT, Fine E, Pribbenow CM, Handelsman J, Carnes M. Searching for excellence and diversity: Increasing the hiring of women faculty at one academic medical center. Acad Med. 2010;85:999–1007. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbf75a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dasgupta N, Asgari S. Seeing is believing: Exposure to counterstereotypic women leaders and its effect on the malleability of automatic gender stereotyping. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2004;40:642–658. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheridan J, Brennan PF, Carnes M, Handelsman J. Discovering directions for change in higher education through the experiences of senior women faculty. J Technol Transf. 2006;31:387–396. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plant EA, Devine PG. Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:811–832. doi: 10.1177/0146167205275304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York NY: Worth Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Isaac C, Kaatz A, Lee B, Carnes M. An educational intervention designed to increase women’s leadership self-efficacy. CBE Lif Sci Educ. 2012;11:307–322. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-02-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheridan JT. [Accessed September 12, 2014];Study of Faculty Worklife at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/facworklife.php.

- 56.West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hox JJ. Multilevel modeling: When and why. In: Balderjahn I, Mathar R, Schader M, editors. Classification, Data Analysis and Data Highways. New York, NY: Springer; 1998. pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klar N, Donner A. The merits of matching in community intervention trials: A cautionary tale. Letter to the editor. Stat Med. 1997;16:1753–1764. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970815)16:15<1753::aid-sim597>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson SG. The merits of matching in community intervention trials: A cautionary tale. Letter to the editor. Stat Med. 1998;17:2149–2151. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980930)17:18<2149::aid-sim897>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson SG, Pyke SD, Hardy RJ. The design and analysis of paired cluster randomized trials: An application of meta-analysis techniques. Stat Med. 1997;16:2063–2079. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970930)16:18<2063::aid-sim642>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ivers NM, Taljaard M, Dixon S, et al. Impact of CONSORT extension for cluster randomised trials on quality of reporting and study methodology: Review of random sample of 300 trials, 2000-8. BMJ. 2011;343:d5886–d5886. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bates DM. [Accessed September 12, 2014];lme4: Mixed-Effects Modeling with R. http://lme4r-forger-projectorg/book/.

- 63.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328:702–708. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garofolo K, Yeatts S, Ramakrishnan V, Jauch E, Johnston K, Durkalski V. The effect of covariate adjustment for baseline severity in acute stroke clinical trials with responder analysis outcomes. Trials. 2013;14:98. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Centola DM. Homophily, networks, and critical mass: Solving the start-up problem in large group collective action. Rationality Society. 2013;25:3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edmondson AC, Kramer RM, Cook KS. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens; pp. 239–272. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Assocation of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed September 12, 2014];E-Learning Seminar: What You Don’t Know: The Science of Unconscious Bias and What To Do About it in the Search and Recruitment Process. ( https://www.aamc.org/members/leadership/catalog/178420/unconscious_bias.html).. [Google Scholar]

- 69.National Center for State Courts. [Accessed September 12, 2014];Helping Courts Address Implicit Bias: Strategies to Reduce the Influence of Implicit Bias. ( http://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Files/PDF/Topics/Gender%20and%20Racial%20Fairness/IB_Strategies_033012.ashx). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ericsson KA, Karmpe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ridgeway CL. Gender, status, and leadership. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:637–655. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heilman M. Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:657–674. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Glass GV. Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ Res. 1976;5:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: Confirmation from meta-analysis. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1181–1209. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.12.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Foster SW, McMurray JE, Linzer M, Leavitt JW, Rosenberg M, Carnes M. Results of a gender-climate and work-environment survey at a midwestern academic health center. Acad Med. 2000;75:653–660. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]