Abstract

Rationale

Cocaine addiction is characterized by alternating cycles of abstinence and relapse and loss of control of drug use despite severe negative life consequences associated with its abuse.

Objective

The objective of the present study was to elucidate critical neural circuits involved in individual vulnerabilities to resumption of cocaine self-administration following prolonged abstinence.

Methods

The subjects were three female rhesus monkeys in prolonged abstinence following a long history of cocaine self-administration. Initial experiments examined the effects of acute cocaine administration (0.3mg/kg, IV) on functional brain connectivity across the whole brain and in specific brain networks related to behavioral control using functional magnetic resonance imaging in fully conscious subjects. Subsequently, these subjects were allowed to resume cocaine self-administration to determine whether loss of basal connectivity within specific brain networks predicted the magnitude of resumption of cocaine intake following prolonged abstinence.

Results

Acute cocaine administration robustly decreased global functional connectivity and selectively impaired top-down prefrontal circuits that control behavior, while sparing connectivity of striatal areas within limbic circuits. Importantly, impaired connectivity between prefrontal and striatal areas during abstinence predicted cocaine intake when these subjects were provided renewed access to cocaine.

Conclusions

Based on these findings, loss of prefrontal to striatal functional connectivity may be a critical mechanism underlying the negative downward spiral of cycles of abstinence and relapse that characterizes cocaine addiction.

Introduction

Cocaine addiction is a significant threat to public health that affects tens of millions of people worldwide every year (Bachman et al. 2011). While initial abuse of cocaine is characterized by low levels of recreational use, cocaine addiction is characterized by escalation of drug use, binge patterns of drug intake, alternating cycles of abstinence and relapse, and loss of control over compulsive drug use despite severe negative consequences (American_Psychiatric_Association 2013). It has been widely reported that only a subset of the many people who abuse cocaine proceed into the compulsive phases of cocaine addiction; some successfully stop using the drug, whereas others develop an intractable and possibly lifelong psychiatric disorder. A central challenge for the field of addiction research is to identify the critical variables that determine these markedly different outcomes.

It is well established that regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) subserve functions such as abstract reasoning, personality, and executive function. Contemporary studies have related specific areas within the PFC to outcome valuation, behavioral inhibition, drug craving, and risky decision making (Everitt and Robbins 2005; Garavan et al. 2000; George and Koob 2010; Jentsch and Taylor 1999; Kalivas 2009; Maas et al. 1998; Volkow et al. 2011). Likewise, elegant studies have shown that many of the behavioral, reinforcing and other abuse-related effects of cocaine are mediated by striatal regions, such as the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), that form important components of brain limbic circuits (Haber and Knutson 2010; Haber and McFarland 1999) (Haber 2003; Haber et al. 2006). Studies have begun to show that interactions between these systems may be important determinants of drug use and relapse. In this regard, studies have consistently shown that cocaine abusers exhibit metabolic and perfusion deficits (Holman et al. 1993; Levin et al. 1994; Strickland et al. 1993; Volkow et al. 1988) and decreased gray matter volumes (Franklin et al. 2002) in the PFC. Animal studies have similarly shown cocaine-induced dysfunction of PFC that correlated with working memory impairments (George et al. 2008). It was recently reported that female active cocaine abusers showed decreased frontal metabolism in response to cocaine-related cues, whereas male active cocaine abusers showed increased metabolism, perhaps beginning to elucidate the higher propensity of females than males to succumb to cocaine addiction (Volkow et al. 2011).

Recent advances in functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (fcMRI) have begun to characterize circuit-level interactions between brain regions in the context of drug abuse and addiction (Ma et al. 2010; Sutherland et al. 2012). The use of fcMRI is attractive experimentally because it has the potential to move the field of neuroscience forward from a focus on specific brain areas to an understanding of the global neural circuits that mediate complex cognitive and motivated behaviors. For example, several studies have reported disruptions in frontal-striatal circuitry in cocaine users (Gu et al. 2010) (Hanlon et al. 2011; Wilcox et al. 2011). Compared to control subjects, cocaine users have lower resting-state functional connectivity within the mesolimbic dopamine system, and lower network connectivity between limbic regions is correlated with duration of cocaine use (Gu et al. 2010). Lower connectivity also was observed between the medial PFC and midbrain dopaminergic regions in cocaine users performing a sustained attention task (Tomasi et al. 2010). In contrast, increased connectivity was reported between ventral striatum and ventromedial PFC in abstinent cocaine users (Wilcox et al. 2011). Clearly, there are multiple variables that can influence the outcome of fcMRI studies in drug addiction, including drug history, acute drug withdrawal, and duration of abstinence. However, chronic drug use is consistently associated with significant changes in functional connectivity within PFC and limbic circuitry that likely contribute to loss of control over drug use and relapse.

Studies have begun to show that interactions between prefrontal and striatal systems may be an important determinant of individual differences in drug use and relapse. The use of fcMRI in laboratory animals presents a significant opportunity to explore network-level connections using prospective approaches and experimental designs with greater control than possible in human subjects. Nonhuman primates represent an excellent animal model to study PFC and limbic circuits because their behavioral repertoires are sophisticated and the rhesus monkey brain has greater homology to the human brain than non-primate animal models, especially in PFC (Preuss 1995). Examination of the direct effects of cocaine administration on functional connectivity is highly relevant for understanding whether impaired functional connectivity is a cause or a consequence of cocaine exposure. In the present study, we determined the effects of acute cocaine administration on functional connectivity between specific regions of the PFC and the NAcc or the amygdala, a component of the extended limbic system, in fully conscious female rhesus monkeys. Moreover, we examined whether connectivity between PFC systems and the NAcc was associated with resumption of cocaine self-administration following a period of extended abstinence.

Materials & Methods

Subjects

The subjects were three (RMv-3, RRg-4 and RBp-3) adult female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) previously involved in intravenous (IV) cocaine self-administration studies to evaluate the etiology, consequences, and treatment of cocaine abuse. Over a period of at least 6 years starting in early adulthood, all three subjects engaged in daily cocaine self-administration with no planned periods of extended abstinence. Drug histories were complex and varied across subjects as reported in published studies for RMv-3 (Kimmel et al. 2008; Lindsey et al. 2004; Murnane and Howell 2010; Wilcox et al. 2002), RRg-4 (Howell et al. 2001; Howell et al. 2002; Kimmel et al. 2008) and RBp-3 (Banks et al. 2009; Howell et al. 2006; Murnane and Howell 2010). Based on self-administration protocols used in these studies and the duration of study assignments, each subject consumed > 10 g of cocaine. This lifetime cocaine history far exceeds drug intake in rhesus monkeys reported to exhibit cocaine-induced cognitive and brain metabolic deficits (Gould et al. 2012) and upregulation of 5-HT2A receptors in PFC (Sawyer et al. 2012). Prior to the present studies, subjects were exposed to a period of forced abstinence during which they were engaged in extensive training to undergo fMRI while fully conscious. Over a period lasting > 2 years, they received infrequent, experimenter-administered psychoactive drugs but no longer engaged in daily self-administration experiments. Cocaine self-administration resumed approximately 10 months after evaluation of the acute effects of cocaine on resting state functional connectivity. This long drug history and prolonged period of abstinence allowed us to examine brain circuitry during abstinence and resumption of cocaine self-administration in a clinically-relevant manner. Between experimental sessions, all subjects were individually housed, and provided access to food daily (e.g., monkey chow and fresh fruit and vegetables), and ad libitum access to water. Animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health's “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University.

Surgery

Each subject was implanted with a chronic indwelling venous catheter and vascular-access port into the femoral or jugular vein under sterile surgical conditions as previously described (Howell and Fantegrossi 2009; Howell and Wilcox 2001). Catheters were regularly flushed with heparinized saline (100 U/mL) to maintain patency.

fcMRI data acquisition

The apparatus and animal habituation protocol have been described in detail previously (Murnane and Howell 2010). Scans were conducted in a Siemens (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) Trio 3 Tesla magnet with 90cm bore using a Siemens CP extremity coil (19 cm inner diameter). Anatomical images were acquired using a 3D single-shot magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence optimized for T1 contrast. Scan parameters were as follows: TR = 2700 ms, TI = 800 ms, TE = 3 ms, 192X192 Matrix, FOV = 96 × 96 mm, 1 NEX, Bandwidth = 190 Hz/pixel, flip angle = 8°, and 9% frequency oversampling yielding a final isotropic resolution of 0.5mm. At least 10 separate collections were averaged off-line for each subject to generate the final anatomical image used for co-registration of the functional data. Anatomical images were acquired in conscious subjects in the imaging apparatus to facilitate co-registration to the functional images. BOLD fMRI images were collected utilizing a gradient echo single-shot echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence, acquired with the following parameters: 47 slices, TR = 4 seconds, TE = 40ms, 64 × 64 Matrix, FOV = 96 × 96 mm, slice thickness = 1.5 mm with no slice gap, 1594 Hz per pixel Bandwidth, and 90° flip angle yielding a final isotropic resolution of 1.5 mm. The first 2 measurements in each time series were discarded to ensure steady-state magnetization. Furthermore, a saturation pulse was applied during each acquisition to minimize extraneous effects at the boundary of the cranium. Field inhomogeneities were mapped using a standard Siemens phase and magnitude image collection sequence for later correction of any EPI image distortions. Functional connectivity scanning was conducted between 10 and 20 minutes after IV infusion of saline or cocaine HCl (0.3 mg/kg). This time period covers the peak neuropharmacological effects of cocaine following IV delivery in rhesus monkeys (Murnane et al. 2013). The effects of saline and cocaine administration were compared to a matched 10-minute period of baseline scanning that was not associated with any infusion. Throughout this study the infusion rate and volume were held constant at 15 ml/min and 4ml, respectively. Cocaine HCl was supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Research Technology Branch, Research Triangle Park, NC) and dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline. In all instances, the dose is expressed as the salt form.

MRI data processing

The MRI data were analyzed with AFNI (Cox 1996), FSL (Smith et al. 2004), and the Brain Connectivity Toolbox (Rubinov and Sporns 2010). Each fcMRI time-series was registered to a base volume, co-registered to the T1W anatomical image, and spatially smoothed with a FWHM = 2 mm isotropic gaussian kernel. Resting state functional connectivity was assessed with seed-based cross correlation analysis. Region of interest (ROI)-averaged time-series were obtained from 3mm spherical seeds placed at anatomical locations in the NAcc (ventral striatum), amygdala, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), anterior cingulate (ACC), orbital prefrontal cortex (oPFC), and cerebellum. As a control to fronto-striatal connectivity, we also examined connectivity between the cerebellum and NAcc. The ROI-averaged time-series served as reference vectors, and functional connectivity maps of each seed ROI were assessed through the cross-correlation coefficient (CC) between the corresponding reference vector and voxel time-series in the rest of the brain. Volumes with excessive (> 1.5 mm) motion were removed from the analysis. For graph analysis, nodes were formed by fcMRI voxels resampled to 2mm × 2mm × 2mm resolution. A binary distance matrix was formed by setting edges with CC > 0.3 to 1 and the rest to 0. The summary measures of network connectivity were 1) the characteristic path length, which is the average of the shortest path lengths between all pairs of nodes in the network, 2) the clustering coefficient of each node, which is the fraction of the node's neighbors that are also neighbors of each other, and 3) the degree centrality of each node, which is the number of other nodes to which a given node is connected. The degree centralities of all nodes were averaged to obtain the mean degree of connectivity. The clustering coefficients of all nodes were averaged to obtain the mean clustering coefficient.

Cocaine Self-administration

To examine whether connectivity between PFC systems and the NAcc was associated with resumption of cocaine use following abstinence, subjects were allowed to once again engage in IV cocaine self-administration. These behavioral experiments were conducted using a three component fixed-ratio 20 (FR20) schedule of reinforcement as previously described (Murnane et al. 2013). Self-administration sessions were conducted in an operant test chamber with a controlled environment (Wilcox et al. 2005). Sessions lasted 80 min and were conducted for 5 days to examine initial resumption of cocaine self-administration following prolonged abstinence. The timing and coordination of experimental events were controlled by Med-PC IV software (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT). Each session began with a 5 min start delay, after which the initiation of the schedule contingencies, including the availability of cocaine, was signaled by the illumination of a white light on the response panel. During the active period of each component, completion of the response requirement resulted in the delivery of a 0.5 ml IV bolus of cocaine over 3 seconds. During each cocaine delivery, the white session light was extinguished and a red light designed to function as a conditioned reinforcer was illuminated on the response panel. Following each cocaine delivery, a 90-sec timeout period was initiated wherein all lights were extinguished and responding had no programmed consequences. Each component lasted 15 min, including both the active and timeout periods, allowing the subjects to earn a maximum of 10 infusions per component. Each of the three components was separated by an intercomponent interval of 15 min wherein all lights were extinguished and responding had no programmed consequences. The unit dose of cocaine was 0.01mg/kg/infusion, yielding a maximum session intake of 0.30 mg/kg. Session intake was calculated as the total number of infusions successfully obtained in a given session multiplied by the unit dose. The response rate was calculated as the total number of responses emitted during the active period divided by the active time throughout the entire session.

Data Analysis

Graphical presentation of all data depicts mean ± SEM, and any points without error bars indicate instances in which the SEM is encompassed by the data. Graphical data presentations were created using GraphPad Prism 4 (La Jolla, CA), and statistical tests were performed using SigmaStat 3 (San Jose, CA).

The summary measures of global network connectivity and measures of connectivity within specific networks following saline and cocaine administration were normalized as a percentage of the baseline value. These data were statistically analyzed by paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, yielding p < 0.008 for statistical significance. The relationship between baseline metrics of functional connectivity and cocaine intake during resumption of cocaine self-administration was analyzed by linear regression analysis, followed by a Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho) = -1. Note p < 0.17 is the minimum possible p-value that can be obtained with the Spearman rank correlation test and a sample size of three subjects. Lastly, we quantitatively determined how acute cocaine administration affected the ratio of connectivity between the PFC and NAcc to connectivity within the striatum. Specifically, this ratio was determined by adding the connectivity between the dlPFC and the NAcc to the connectivity between the ACC and the NAcc. This sum was then divided by the connectivity between the NAcc and itself plus the caudate (i.e., intrastriatum connectivity). The ratio provides a measure of top-down PFC connectivity to the striatum as a function of connectivity within the striatum itself. A higher value indicates that top-down connectivity is relatively strong compared to connectivity within the striatum. The oPFC was not used to calculate this ratio because cocaine had no significant effect on oPFC to NAcc connectivity.

Results

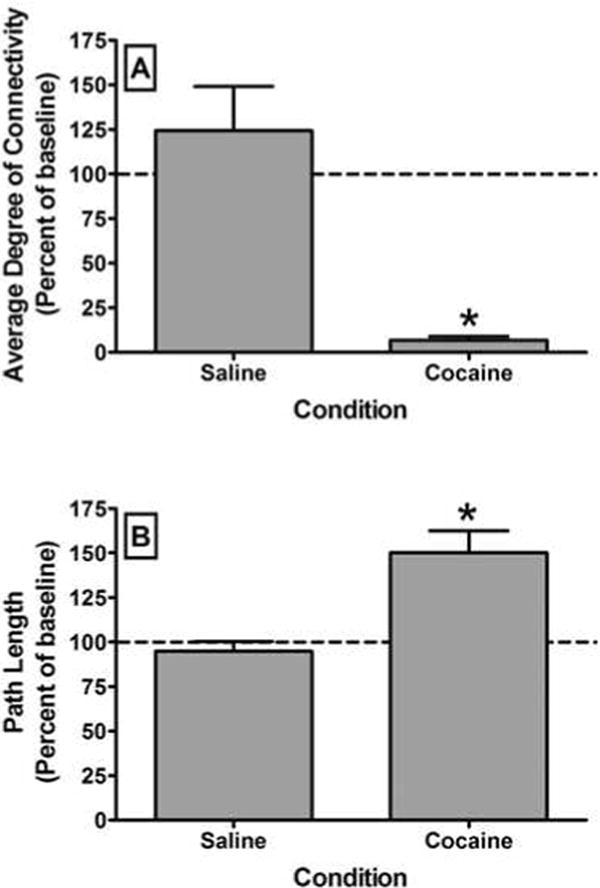

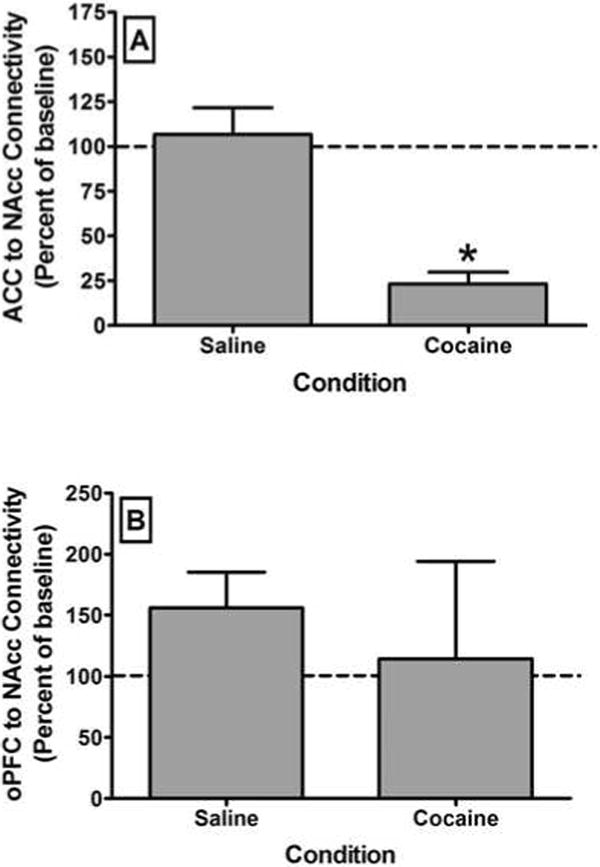

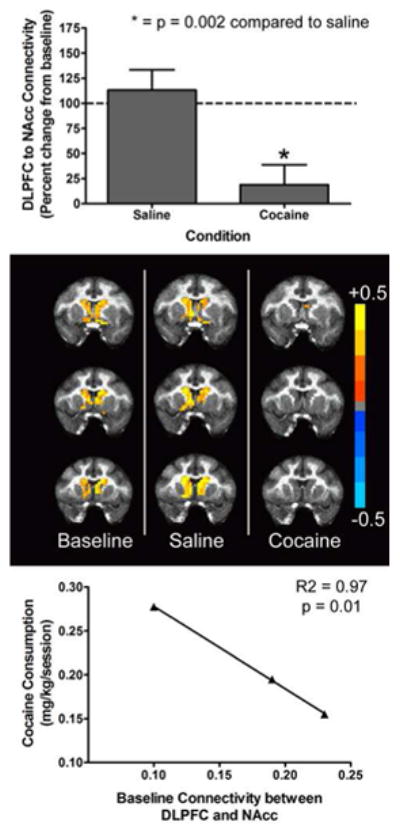

Following saline infusion, there was no significant change in global network integrity compared to baseline across any of the network-wise measures. In contrast, following cocaine infusion, there was a dramatic and significant (t3 = 4.48; p < 0.008) decrease in the average degree of connectivity (degree centrality averaged across all nodes in the brain) (Figure 1A). Likewise, there was a significant (t3 = -3.78; p < 0.008) increase in the characteristic path length (Figure 1B). In contrast, there was no significant change in the clustering coefficient (t3 = 2.23; p = 0.15) following cocaine administration. Hence, acute administration of cocaine induced a global decrease in functional brain connectivity, and the average degree of connectivity was the most sensitive measure of this effect. Cocaine had no significant effect on connectivity between the cerebellum and the NAcc (data not shown). It is important to note, however, that the cerebellum displayed a low level of connectivity with the NAcc even at baseline. In the PFC, cocaine significantly (t3 = 8.72; p < 0.008) decreased connectivity between the ACC and the NAcc (Figure 2A) but had no significant effect on connectivity between the oPFC and the NAcc (Figure 2B). Interestingly, there was considerable between-subject variability in the effects of acute cocaine administration on connectivity between the oPFC and NAcc, with cocaine either increasing or decreasing connectivity between these areas across the subjects. As with ACC to NAcc connectivity, cocaine significantly (t3 = 8.89; p < 0.008) decreased connectivity between the dlPFC and the NAcc (Figure 3, Top). This loss of connectivity was apparent in both the quantitative data and in images of the striatum color coded to voxel-level connectivity with the dlPFC (Figure 3, Middle). Lastly, cocaine had no significant effect on connectivity between the amygdala and the ACC (t3 = 1.03; p = 0.41), oPFC (t3 = 1.43; p = 0.29) or dlPFC (t3 = 5.45; p = 0.03). Collectively, these findings indicate that the acute effects of cocaine on functional connectivity are selective for different brain networks.

Figure 1.

Effects of acute cocaine administration on global functional connectivity as indexed by the average degree of connectivity (A) and characteristic path length (B). All bars represent the group mean ± SEM. Abscissae: The condition under which scanning was conducted. Ordinates: Average degree of connectivity or characteristic path length expressed as a percentage of the baseline value. Asterisks represent a significant difference (P < 0.008) between the conditions as assessed by a paired t-test.

Figure 2.

Effects of acute cocaine administration on functional connectivity between the anterior cingulate (ACC) and the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) (A) or between the orbital prefrontal cortex (oPFC) and the NAcc (B). Mean connectivity was determined by correlating the time-course of activity within the prefrontal seed region and each voxel within the NAcc. All bars represent the group mean ± SEM. Abscissae: The condition under which scanning was conducted. Ordinates: Average degree of connectivity expressed as a percentage of the baseline value. Asterisks represent a significant difference (P < 0.008) between the conditions as assessed by a paired t-test.

Figure 3.

Effects of acute cocaine administration on functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and the relationship between dlPFC to NAcc functional connectivity and cocaine intake. Top Panel shows a marked reduction in dlPFC to NAcc functional connectivity following acute cocaine administration. Middle Panel shows color-coded maps of connectivity between all voxels within the medial striatum and a seed region in the dlPFC in a representative subject across all three conditions. Bottom Panel shows the correlation between baseline functional connectivity between the dlPFC and NAcc and cocaine intake in self-administration studies. All bars or points represent the group mean ± SEM. Abscissae: The condition under which scanning was conducted (Top) or baseline functional connectivity between the dlPFC and NAcc expressed as a correlation coefficient (Bottom). Ordinates: Functional connectivity between the dlPFC and NAcc expressed as a percentage of the baseline value (Top) or daily cocaine intake, averaged over the first 5 sessions, expressed as a mg/kg/session for individual subjects (Bottom). Asterisks represent a significant difference (P < 0.008) between cocaine and saline as assessed by a paired t-test.

Linear regression analysis was used to examine whether connectivity between PFC systems and the NAcc was associated with resumption of cocaine self-administration following abstinence. Daily session cocaine intake for individual subjects is shown in Table 1. There was an inverse relationship between cocaine intake and connectivity between the ACC and the NAcc (data not shown), but this relationship did not reach statistical significance. In contrast to this lack of significance for the ACC, loss of connectivity between the dlPFC and the NAcc significantly (R2 = 0.97; p = 0.01) predicted the level of cocaine intake during resumption of drug self-administration (Figure 3, Bottom). The more conservative Spearman rank correlation coefficient (p = 0.17) was the minimum possible p-value that could be obtained with a sample size of three subjects. Collectively, these data indicate that loss of top-down control over striatal areas that comprise the limbic circuitry may be a critical determinant of cocaine intake following a period of abstinence.

Table 1.

| Subject | Session | Infusions | Rate (resp/sec) | Intake (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBP-3 | 1 | 14 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| 2 | 16 | 0.20 | 0.16 | |

| 3 | 24 | 0.71 | 0.24 | |

| 4 | 24 | 0.66 | 0.24 | |

| 5 | 23 | 0.50 | 0.23 | |

| Mean | 19.5 | 0.43 | 0.20 | |

| RMv-3 | 1 | 17 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| 2 | 15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |

| 3 | 14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | |

| 4 | 16 | 0.19 | 0.16 | |

| 5 | 15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |

| Mean | 15.5 | 0.18 | 0.16 | |

| RRg-4 | 1 | 27 | 1.11 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 28 | 1.93 | 0.28 | |

| 3 | 28 | 2.49 | 0.28 | |

| 4 | 28 | 1.89 | 0.28 | |

| 5 | 27 | 1.18 | 0.27 | |

| Mean | 27.8 | 1.72 | 0.28 |

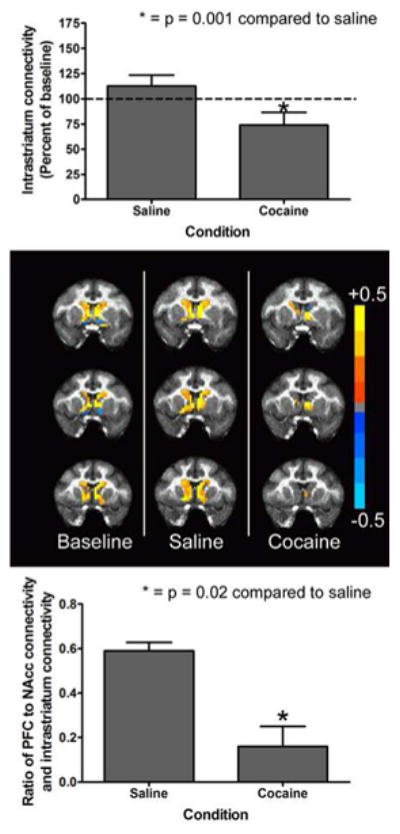

Subsequent analyses determined how acute cocaine administration affected connectivity within the NAcc and between the NAcc and other areas of the medial striatum that likely contribute to the abuse-related effects of cocaine. Acute cocaine administration significantly (t3 = 6.09; p < 0.008) decreased connectivity within the striatum (Figure 4, Top). However, this effect was far less robust than loss of PFC to NAcc connectivity. As was apparent in the color coded images (Figure 4, Middle), loss of intrastriatal connectivity was less robust than loss of connectivity between the PFC and the NAcc. Hence, cocaine decreased connectivity between the NAcc and other areas of the medial striatum but had little effect on connectivity within the NAcc itself. Lastly, the ratio of connectivity between the PFC and NAcc to connectivity within the striatum was evaluated. Acute cocaine administration significantly (t3 = 5.99; p < 0.008) decreased this ratio (Figure 4, Bottom). These data indicate that cocaine selectively spares the function of the limbic circuitry while impairing top-down prefrontal control over these brain areas.

Figure 4.

Effects of acute cocaine administration on functional connectivity within the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and between the NAcc and other areas of the medial striatum. We termed the combination of these connectivities “intrastriatal connectivity.” Top Panel shows a modest but significant reduction in intrastriatal connectivity following acute cocaine administration. Middle Panel shows color-coded maps of connectivity between all voxels within the medial striatum and a seed region in the NAcc in a representative subject across all three conditions. Bottom Panel shows a robust reduction in the ratio of prefrontal to NAcc connectivity (the sum of anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to NAcc connectivity) and intrastriatal connectivity. All bars represent the group mean ± SEM. Abscissae: The condition under which scanning was conducted (Top & Bottom). Ordinates: Intrastriatal connectivity expressed as a percentage of the baseline value (Top) or the ratio of prefrontal to intrastriatal connectivity expressed as a correlation coefficient (Bottom). Asterisks represent a significant difference (P < 0.05) between cocaine and saline as assessed by a paired t-test.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the effects of acute cocaine administration on brain functional connectivity in female rhesus monkeys with a long history of cocaine self-administration. Subjects were scanned while fully conscious during a protracted period of forced abstinence and then allowed to resume cocaine self-administration to elucidate the relationship between neurobiological alterations and cocaine intake after extended abstinence. An acute cocaine challenge robustly impaired global functional connectivity and selectively impaired top-down, prefrontal control over striatal regions that comprise the limbic circuitry, while sparing connectivity of striatal areas within limbic circuits. Importantly, impaired connectivity between the dlPFC and NAcc predicted initial resumption of cocaine self-administration. Consistent with the findings observed, a series of studies has shown that cocaine-dependent humans exhibit dysregulation of prefrontal cortical structure and function (Lane et al. 2010; Lim et al. 2002; Volkow et al. 1988; Volkow et al. 2011). Indeed, a recent review article convincingly argued that loss of prefrontal cortical function during abstinence is the most reliable clinical biomarker of relapse (Hanlon et al. 2013). Although comprehensive prospective studies have not yet been conducted, it is reasonable to suggest that a history of repeated disruption of PFC to NAcc connectivity by chronic exposure to cocaine could persistently compromise this circuitry. Moreover, our data suggest that persistent disruption of this circuitry may predispose individuals to further cocaine use and relapse, which may then further compromise the integrity of top-down control over drug taking and further impair the capacity of PFC regions to inhibit drug use. Hence, this loss of PFC to NAcc functional connectivity may be a critical mechanism underlying the negative downward spiral of cycles of drug taking, abstinence, and relapse that characterizes cocaine addiction.

Several clinical studies have begun to integrate functional connectivity measures with cognitive performance in the context of cocaine addiction. Compared to controls, cocaine abusers showed lower positive functional connectivity between the midbrain and subcortical and PFC areas, which was associated with deficits in sustained attention (Tomasi et al. 2010). Cocaine-positive subjects showed significantly weaker and shorter negative coherence between subcortical and PFC areas during attempted inhibition of craving than cocaine-negative subjects (Lam et al. 2013). Cocaine-dependent subjects also showed functional connectivity abnormalities that significantly predicted impaired performance on delayed discounting and reversal learning tasks (Camchong et al. 2011). Consistent with these findings, other researchers have shown that cocaine abusers exhibit impaired cortical-striatal connectivity during the performance of a simple motor task (Hanlon et al. 2011) and impaired resting connectivity in mesocorticolimbic circuits (Gu et al. 2010). These studies strongly support the feasibility of using fcMRI to study the neural circuitry critical for cocaine use and relapse and disruptions of this circuitry related to a history of cocaine abuse.

Examination of the direct effects of cocaine administration on functional connectivity is highly relevant for understanding whether impaired functional connectivity is a cause or a consequence of cocaine exposure. In fact, very few studies have examined the acute effects of psychoactive drugs on functional connectivity. In a recent study, the acute effects of oral methylphenidate administration were characterized in 18 non-abstaining subjects with cocaine use disorders, and functional connectivity was evaluated using a seed voxel correlation approach (Konova et al. 2013). Methylphenidate strengthened several corticolimbic and corticocortical connections shown previously to be reduced in individuals with cocaine use disorders, including the dorsal frontoparietal attention network (Kelly et al. 2011) and mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathways (Gu et al. 2010). The authors suggest this may constitute a mechanism by which methylphenidate could facilitate behavioral control in cocaine addiction. In a separate doubleblind, placebo-controlled study, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) was orally administered to 25 healthy participants with at least one previous experience with MDMA (Carhart-Harris et al. 2014). None of the participants had used MDMA for at least 7 days or other drugs for at least 48 hours. Decreases in resting state functional connectivity were observed between midline cortical regions, the medial prefrontal cortex, and medial temporal lobe regions, and increases were observed between the amygdala and hippocampus. Moreover, there were trend-level correlations between these effects and ratings of intensity and positive subjective effects. Clearly, further research is required to define the exact mechanisms by which acute stimulant-induced changes in brain activity translate to addictive behavior.

Interestingly, in the present study cocaine had no significant effect on connectivity between the oPFC and the NAcc or between the amygdala and any region of the PFC. Hence, these findings indicate that the acute effects of cocaine on functional connectivity show some selectivity for different brain networks. However, it should be noted that studies have reported decreased connectivity between the amygdala and the medial PFC in cocaine addicts (Gu et al. 2010), and increased connectivity between the amygdala and oPFC in chronic heroin users on methadone maintenance treatment (Ma et al. 2010). Moreover, a robust decrease in functional connectivity between the amygdala and dlPFC was observed in the present study, although the effect did not reach statistical significance. Hence, cocaine-induced changes in functional connectivity between the PFC and amygdala require further evaluation.

There are several limitations to this preliminary study in nonhuman primates that should be acknowledged. The study was restricted to three female rhesus monkeys, providing limited statistical power, and it is not clear whether the results would generalize to male subjects. Importantly, all subjects had a complex drug history that varied among individuals and there were no drug naïve controls for comparisons. Cocaine self-administration resumed approximately 10 months after evaluation of the acute effects of cocaine on resting state functional connectivity. The study would have benefitted from a shorter interval between these primary outcome measures. Moreover, the acute effects of cocaine on functional connectivity were limited to a single dose. It would have been informative to evaluate multiple drug doses that would address potential individual differences in drug sensitivity. Despite these limitations, it is somewhat remarkable that the acute effects of cocaine were so robust, providing statistically significant effects. The effort invested in imaging fully conscious nonhuman primates was clearly a major benefit. Overall, the results are quite orderly and will begin to bridge acute drug effects with long-term consequences that are evident during drug abstinence. Ongoing, longitudinal studies initiated in a larger cohort of drug naïve subjects will extend the current pilot study to incorporate a well-controlled drug history with multi-dose drug challenges.

In summary, the purpose of the present study was to elucidate potential mechanisms underlying initial resumption of drug self-administration following a period of prolonged abstinence. The analyses focused on the dlPFC, ACC, and oPFC in the frontal lobe because these areas have been implicated in processes such as outcome valuation, behavioral inhibition, drug craving, and risky decision making. The underlying framework through which we have interpreted our findings is that the abuse-related effects of cocaine are mediated by the NAcc and other elements of the limbic circuitry, and the functions of these areas are inhibited by top-down prefrontal executive control over behavior. Acute cocaine administration selectively impaired top-down prefrontal circuits that control behavior, while sparing connectivity of striatal areas within limbic circuits. Importantly, impaired connectivity between prefrontal and striatal areas during abstinence predicted cocaine intake when these subjects were provided renewed access to cocaine. Collectively, the data indicate that loss of top-down control over striatal areas that comprise the limbic circuitry may be a critical determinant of cocaine use following abstinence.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank both Juliet Brown and Lisa Neidert for their expert technical assistance. These studies were supported by USPHS grants DA010344, DA034232, DA031246, and RR00165. They were furthermore supported by an award (UL1RR025008) from the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute and by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs ODP51OD11132.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- American_Psychiatric_Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Wallace JM. Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between parental education and substance use among U.S. 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students: findings from the Monitoring the Future project. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:279–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Andersen ML, Murnane KS, Meyer RC, Howell LL. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine and diphenhydramine combinations in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205:467–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1555-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camchong J, MacDonald AW, 3rd, Nelson B, Bell C, Mueller BA, Specker S, Lim KO. Frontal hyperconnectivity related to discounting and reversal learning in cocaine subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:1117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris RL, Murphy K, Leech R, Erritzoe D, Wall MB, Ferguson B, Williams LT, Roseman L, Brugger S, De Meer I, Tanner M, Tyacke R, Wolff K, Sethi A, Bloomfield MA, Williams TM, Bolstridge M, Stewart L, Morgan C, Newbould RD, Feilding A, Curran HV, Nutt DJ. The Effects of Acutely Administered 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine on Spontaneous Brain Function in Healthy Volunteers Measured with Arterial Spin Labeling and Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Resting State Functional Connectivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1481–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TR, Acton PD, Maldjian JA, Gray JD, Croft JR, Dackis CA, O'Brien CP, Childress AR. Decreased gray matter concentration in the insular, orbitofrontal, cingulate, and temporal cortices of cocaine patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:134–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Pankiewicz J, Bloom A, Cho JK, Sperry L, Ross TJ, Salmeron BJ, Risinger R, Kelley D, Stein EA. Cue-induced cocaine craving: neuroanatomical specificity for drug users and drug stimuli. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1789–98. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, Koob GF. Individual differences in prefrontal cortex function and the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:232–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, Mandyam CD, Wee S, Koob GF. Extended access to cocaine self-administration produces long-lasting prefrontal cortex-dependent working memory impairments. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2474–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RW, Gage HD, Nader MA. Effects of chronic cocaine self-administration on cognition and cerebral glucose utilization in Rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:856–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Salmeron BJ, Ross TJ, Geng X, Zhan W, Stein EA, Yang Y. Mesocorticolimbic circuits are impaired in chronic cocaine users as demonstrated by resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2010;53:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN. The primate basal ganglia: parallel and integrative networks. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26:317–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Kim KS, Mailly P, Calzavara R. Reward-related cortical inputs define a large striatal region in primates that interface with associative cortical connections, providing a substrate for incentive-based learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8368–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0271-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, McFarland NR. The concept of the ventral striatum in nonhuman primates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:33–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon CA, Beveridge TJ, Porrino LJ. Recovering from cocaine: insights from clinical and preclinical investigations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:2037–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon CA, Wesley MJ, Stapleton JR, Laurienti PJ, Porrino LJ. The association between frontal-striatal connectivity and sensorimotor control in cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:240–3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman BL, Mendelson J, Garada B, Teoh SK, Hallgring E, Johnson KA, Mello NK. Regional cerebral blood flow improves with treatment in chronic cocaine polydrug users. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:723–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Fantegrossi WE. Intravenous Drug Self-Administration in Nonhuman Primates. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Hoffman JM, Votaw JR, Landrum AM, Jordan JF. An apparatus and behavioral training protocol to conduct positron emission tomography (PET) neuroimaging in conscious rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;106:161–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Hoffman JM, Votaw JR, Landrum AM, Wilcox KM, Lindsey KP. Cocaine-induced brain activation determined by positron emission tomography neuroimaging in conscious rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;159:154–60. doi: 10.1007/s002130100911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Wilcox KM. The dopamine transporter and cocaine medication development: drug self-administration in nonhuman primates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Wilcox KM, Lindsey KP, Kimmel HL. Olanzapine-induced suppression of cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:585–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:373–90. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, Zuo XN, Gotimer K, Cox CL, Lynch L, Brock D, Imperati D, Garavan H, Rotrosen J, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Reduced interhemispheric resting state functional connectivity in cocaine addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:684–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel HL, Negus SS, Wilcox KM, Ewing SB, Stehouwer J, Goodman MM, Votaw JR, Mello NK, Carroll FI, Howell LL. Relationship between rate of drug uptake in brain and behavioral pharmacology of monoamine transporter inhibitors in rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konova AB, Moeller SJ, Tomasi D, Volkow ND, Goldstein RZ. Effects of methylphenidate on resting-state functional connectivity of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathways in cocaine addiction. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:857–68. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SC, Wang Z, Li Y, Franklin T, O'Brien C, Magland J, Childress AR. Wavelet-transformed temporal cerebral blood flow signals during attempted inhibition of cue-induced cocaine craving distinguish prognostic phenotypes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Ma L, Hasan KM, Kramer LA, Zuniga EA, Narayana PA, Moeller FG. Diffusion tensor imaging and decision making in cocaine dependence. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JM, Holman BL, Mendelson JH, Teoh SK, Garada B, Johnson KA, Springer S. Gender differences in cerebral perfusion in cocaine abuse: technetium-99m-HMPAO SPECT study of drug-abusing women. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1902–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KO, Choi SJ, Pomara N, Wolkin A, Rotrosen JP. Reduced frontal white matter integrity in cocaine dependence: a controlled diffusion tensor imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:890–5. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey KP, Wilcox KM, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Plisson C, Carroll FI, Rice KC, Howell LL. Effects of dopamine transporter inhibitors on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys: relationship to transporter occupancy determined by positron emission tomography neuroimaging. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:959–69. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Liu Y, Li N, Wang CX, Zhang H, Jiang XF, Xu HS, Fu XM, Hu X, Zhang DR. Addiction related alteration in resting-state brain connectivity. Neuroimage. 2010;49:738–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas LC, Lukas SE, Kaufman MJ, Weiss RD, Daniels SL, Rogers VW, Kukes TJ, Renshaw PF. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:124–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane KS, Howell LL. Development of an apparatus and methodology for conducting functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with pharmacological stimuli in conscious rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;191:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane KS, Winschel J, Schmidt KT, Stewart LM, Rose SJ, Cheng K, Rice KC, Howell LL. Serotonin 2A receptors differentially contribute to abuse-related effects of cocaine and cocaine-induced nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopamine overflow in nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13367–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1437-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss TM. Do rats have prefrontal cortex? The rose-woolsey-akert program reconsidered. J Cogn Neurosci. 1995;7:1–24. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1995.7.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1059–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer EK, Mun J, Nye JA, Kimmel HL, Voll RJ, Stehouwer JS, Rice KC, Goodman MM, Howell LL. Neurobiological changes mediating the effects of chronic fluoxetine on cocaine use. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1816–24. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland TL, Mena I, Villanueva-Meyer J, Miller BL, Cummings J, Mehringer CM, Satz P, Myers H. Cerebral perfusion and neuropsychological consequences of chronic cocaine use. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5:419–27. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland MT, McHugh MJ, Pariyadath V, Stein EA. Resting state functional connectivity in addiction: Lessons learned and a road ahead. Neuroimage. 2012;62:2281–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi D, Volkow ND, Wang R, Carrillo JH, Maloney T, Alia-Klein N, Woicik PA, Telang F, Goldstein RZ. Disrupted functional connectivity with dopaminergic midbrain in cocaine abusers. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Mullani N, Gould KL, Adler S, Krajewski K. Cerebral blood flow in chronic cocaine users: a study with positron emission tomography. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:641–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Telang F, Goldstein RZ, Alia-Klein N, Wong C. Reduced metabolism in brain “control networks” following cocaine-cues exposure in female cocaine abusers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox CE, Teshiba TM, Merideth F, Ling J, Mayer AR. Enhanced cue reactivity and frontostriatal functional connectivity in cocaine use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox KM, Kimmel HL, Lindsey KP, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Howell LL. In vivo comparison of the reinforcing and dopamine transporter effects of local anesthetics in rhesus monkeys. Synapse. 2005;58:220–8. doi: 10.1002/syn.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox KM, Lindsey KP, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Martarello L, Carroll FI, Howell LL. Self-administration of cocaine and the cocaine analog RTI-113: relationship to dopamine transporter occupancy determined by PET neuroimaging in rhesus monkeys. Synapse. 2002;43:78–85. doi: 10.1002/syn.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]