Abstract

Background

It is well established that reactive astrocytes express L-type calcium channels (LTCC), but their functional role is completely unknown. We have recently shown that reactive astrocytes highly express the CaV1.2 α1-subunit around β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques in an Alzheimer mouse model. The aim of the present study was to explore whether Aβ peptides may regulate the mRNA expression of all LTCC subunits in primary mouse astrocytes in culture.

Methods

Confluent primary astrocytes were incubated with 10 μg/ml of human or murine Aβ or the toxic fragment Aβ25–35 for 3 days or for 3 weeks. The LTCC subunits were determined by quantitative RT-PCR.

Results

Our data show that murine Aβ42 slightly but significantly increased CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 expression when incubated for 3 days. This acute treatment with murine Aβ enhanced β2 and β3 mRNA levels but decreased α2δ-2 mRNA expression. When astrocytes were incubated for 3 weeks, the levels of CaV1.2 α1 were significantly decreased by the murine Aβ and the toxic fragment. As a control, the protein kinase C-ε activator DCP-LA displayed a decrease in CaV2.1 expression.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data show that Aβ can differentially regulate LTCC expression in primary mouse astrocytes depending on incubation time.

Keywords: L-type calcium channel, Astrocytes, Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, mRNA, β-Amyloid

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder in elderly people. The extracellular deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, intraneuronal tau pathology, synaptic loss, cholinergic neuronal cell death and inflammatory processes are the major neuropathological hallmarks of AD. A possible role for Ca2+ dysregulation in the aging brain and in AD has been postulated [1, 2]. L-type calcium channels (LTCC) are assumed to be involved in Ca2+ homeostasis [3]. LTCC consist of a pore-forming α1-subunit (CaV1.1, 1.2, 1.3 or 1.4), which plays a role in voltage sensing and serves as a drug-binding site. Auxiliary β- and α2δ-subunits are responsible for membrane trafficking and the modulation of channel properties [4, 5].

Besides their occurrence in neurons, LTCC are also expressed by astrocytes [6–8]. After brain injury, glial cells become reactive and highly express glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [9]. In contrast, neuron-glial antigen 2 glia also reacts to degenerative stimuli but does not express GFAP [10]. It is well established that brain injury leads to an upregulation of CaV1.2 α1-subunits in reactive GFAP-positive astrocytes [11, 12]. The expression of CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 channels in primary astrocytes is well established [8, 13–15], but their function is not completely understood. We have recently shown that CaV1.2 α1-subunits are highly expressed in reactive astrocytes surrounding Aβ plaques in a transgenic amyloid precursor protein-overexpressing mouse model [12, 16]. In addition, we have recently reported that reactive astrocytes around plaques do not coexpress the auxiliary β4-subunit [16]. The role and function of these calcium channels in astrocytes are not known. In order to investigate the role of astroglial LTCC channels, it would be necessary to explore the cellular regulation of all LTCC subunits in the astroglia. Unfortunately, no specific and immunohistochemically selective antibodies are available for most of the LTCC subunits.

The principal question arises whether astroglial CaV1.2 α1-subunit expression is caused by the AD pathology (including inflammation, oxidative stress or Ca2+ dysregulation) or whether it is caused directly by plaque generation induced by the Aβ cascade. In the latter case, the question arises whether the plaques per se (containing aggregated Aβ peptides) or the soluble Aβ peptides alone may induce astroglial CaV1.2 α1-subunit expression. And third, it is possible that CaV1.2 α1-subunit expression is a consequence of the activation and reaction of the astrocytes rather than independent of plaques. In order to study these questions, we cultured primary astrocytes from the murine cortex to explore whether exogenous Aβ peptides directly regulate expression of the LTCC channel. We show that Aβ peptides moderately enhance LTCC expression after short incubation but decrease the expression after longer incubation.

Material and Methods

Animals

Male and female wild-type B6129SF2/J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Minn., USA). All mice were housed according to standard animal care protocols, fed ad libitum with regular animal diet and maintained in a pathogen-free environment. All experiments were approved by the Austrian Ministry of Science and Research and conformed to the Austrian guidelines on animal welfare and experimentation.

Primary Astrocyte Cell Culture

Primary astrocytes were cultured as previously reported, with slight modifications [17, 18]. Postnatal-day 4 mice were rapidly sacrificed. The cortices were dissected and pooled in 1.5 ml of pre-warmed sterile 0.25% trypsin solution. With a scalpel, the tissue was cut into small pieces. After an incubation time of 15 min at 37°C, the trypsin was discarded. To obtain single cells, the remaining tissue was passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J., USA) into a tube containing 1 ml of horse serum (16050-122; Gibco, USA) and 500 μl of DNase I (10 mg/ml; Roche Applied Sciences, Vienna, Austria). After 5 min of centrifugation (1,500 rpm), the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of glial medium (5% horse serum, 0.5% FCS in 100 ml OptiMEM; Gibco). The cells were centrifuged again for 5 min at 1,500 rpm. The pellet was then resuspended in 2 ml of glial medium and transferred onto collagen-coated 6-well plates (150 μl of cells/well). The medium was changed 24 h after preparation and the cells were cultured for 2 weeks to become confluent. To remove residual microglia, the cells were shaken (180 rpm, 37°C) overnight and then again cultured in fresh medium. Astrocytes adhere to the surface, while other cell types peel off with the supernatant. We obtained a high astroglial purity with <0.1% oligodendrocytes or microglia.

Treatment with Exogenous Stimuli

Primary confluent astrocytes were incubated for either 3 days or 3 weeks by various treatments to induce cell activation: human Aβ42 (10 μg/ml; Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif., USA); murine Aβ42 (10 μg/ml; Calbiochem); the toxic Aβ25–35 fragment (10 μg/ml; A4559; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo., USA); protein kinase C (PKC)-ε activator (3 μg/ml; DCP-LA, D5318; Sigma); and cAMP analog (12 μg/ml; Cpt-cAMP, C3912; Sigma). For some experiments, Aβ25–35 treatments were performed at an acidic pH of 6.7 or with 45 μmol/l H2O2 in order to enhance astrogliosis. The 3-week treatments were conducted with 1% horse serum in glial medium.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described [16]. Astrocytes were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde/10 mmol/l PBS (4°C, 30 min). After fixation, the cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS (T-PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, shaking. Subsequently, the astrocytes were pretreated for 20 min with 5% methanol/1% H2O2/PBS, and after thorough rinsing, the cells were blocked with 20% horse serum/0.2% BSA/T-PBS. Finally, they were incubated for 2–3 days at 4°C with a primary antibody diluted in 0.2% BSA/T-PBS. The primary antibodies used for this study were: rabbit anti-CaV1.2 α1-subunit (1:2,000; Sigma C1603); chicken anti-GFAP (1:2,000; Millipore AB5541); and rabbit polyclonal to glutamine synthetase (1:2,000; GluS; Abcam). After incubation, the cells were washed in PBS and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies: α-rabbit (1:200; Vector V1011) or α-chicken (1:200; Vector K0722). After 1 h of incubation, the astrocytes were washed with PBS and incubated with an avidin-biotin complex solution (Vectastain Elite ABC reagent; Vector Laboratories) for another 1 h. After washing with 50 mmol/l Tris-buffered saline, the signal was detected by using 0.5 mg/ml 3,3′-diaminobenzidine including 0.003% H2O2 as a substrate in Tris-buffered saline for 3–8 min. The reaction was terminated by adding Tris-buffered saline. The stained cells were rinsed in 10 mmol/l PBS, at a pH of 7.4. Control experiments for all antibodies were conducted by omitting the primary antibody. Staining was visualized with an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope and pictures were captured with Openlab software connected to an Apple computer. For colocalization studies, fluorescence immunohistochemistry was performed similarly as for chromogenic staining but without methanol pretreatment. After incubation with the primary antibody, the cells were washed in PBS and incubated with fluorescent Alexa 488 secondary antibodies (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Vienna, Austria). Additionally, DAPI staining was performed. After 1 h of incubation, the astrocytes were washed and ready for analysis.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative TaqMan-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as recently described [16]. Astrocytes were rinsed quickly with PBS to remove the medium. Subsequently, by the addition of 600 μl of Buffer RLT (RNeasy Mini Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), cells were harvested with a cell scraper. Three wells from a 6-well dish were pooled. The astrocytes were disrupted by using QIAshredder columns, and total RNA was extracted utilizing the RNeasy Mini Kit. RNA concentrations were determined photometrically using BioPhotometer 6131 (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Reverse transcription was performed on 1 μg of RNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif., USA) and random hexamer primers (Promega, Madison, Wisc., USA). The RT mix was incubated for 60 min at 37°C. The relative abundance of different CaV subunit transcripts was assessed by TaqMan quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) using a standard curve method based on PCR products of known concentration in combination with normalization using the most stable control genes, as previously described [19]. TaqMan gene expression assays specific for all high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channel subunits (α1, β and α2δ), designed to span exon-exon boundaries, were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif., USA). The following assays (Applied Biosystems) were used [name (gene symbol), assay ID]: CaV1.1 (Cacna1s), Mm00489257_m1; CaV1.2 (Cacan1c), Mm00437953_m1; CaV1.3 (Cacna1d), Mm01209919_m1; CaV1.4 (Cacna1f), Mm00490443_m1; CaV2.1 (Cacna1a), Mm00432190_m1; CaV2.2 (Cacna1b), Mm00432226_m1; CaV2.3 (Cacna1e), Mm00494444_m1; β1 (Cacnb1), Mm00518940_m1; β2 (Cacnb2), Mm00659092_m1; β3 (Cacnb3), Mm00432233_m1; β4 (Cacnb4) Mm00521623_m1; α2δ-1 (Cacna2d1), Mm00486607_m1; α2δ-2 (Cacna2d2), Mm00457825_m1; α2δ-3 (Cacna2d3), Mm00486613_m1; and α2δ-4 (Cacna2d4), Mm01190105_m1. The endogenous control genes (Applied Biosystems) included were [name (gene symbol), assay ID]: γ-cytoplasmic actin (Actb), Mm00607939_s1; β2-microglobulin (B2m), Mm00437762_m1; glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh), Mm99999915_g1; hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Hprt1), Mm00446968_m1; succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A (Sdha), Mm01352363_m1; tata box-binding protein (Tbp), Mm00446973_m1; and transferrin receptor (Tfrc), Mm00441941_m1. qRT-PCR (50 cycles) was performed in duplicates, using 20 ng total RNA equivalents of cDNA and the specific TaqMan gene expression assay for each 20-μl reaction in TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Analyses were performed using the 7500 Fast System (Applied Biosystems). The Ct values for each CaV gene expression assay were recorded for each individual preparation. To allow a direct comparison between expression levels in different tissues, we normalized all experiments to Tbp, Hprt1 and Actb, which were determined to be the most stably expressed reference genes across all preparations and time points [20]. Subsequently, normalized molecule numbers were calculated for each CaV subunit from their respective standard curve [19].

Data Analysis and Statistics

The data were organized and analyzed using MS Excel and KaleidaGraph statistical software. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Fisher protected least significant difference (PLSD) post hoc test, and p < 0.05 represents significance.

Results

Astroglial Cultures

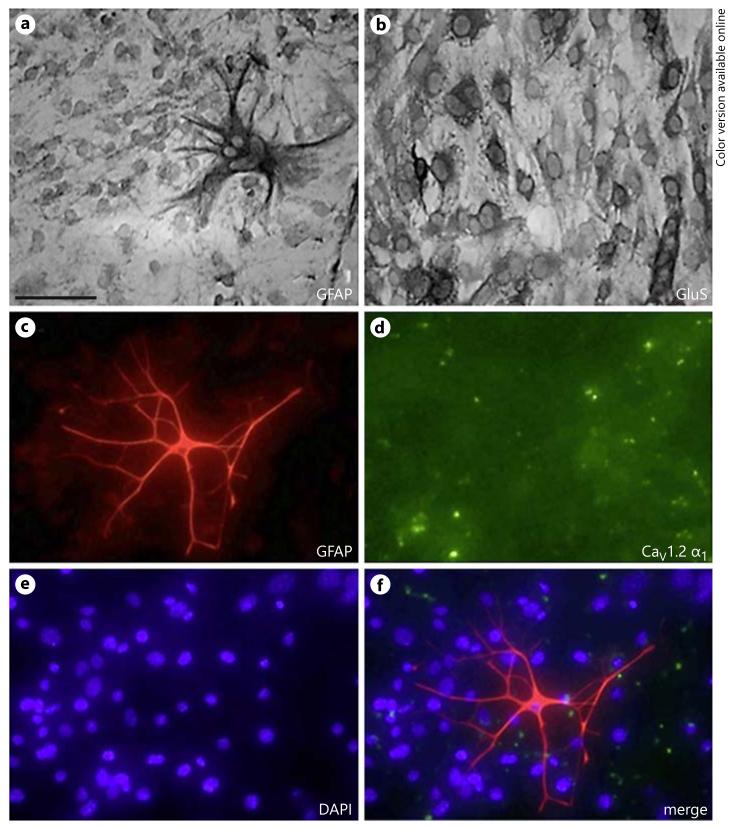

Immunohistochemistry for GFAP revealed a moderate staining of confluent astrocytes, while only occasionally, large reactive strong GFAP astrocytes were visible (fig. 1a, c). Immunostaining for glutamate synthetase showed that the whole confluent layer was strongly positive (fig. 1b). The reactive GFAP-positive astrocytes were also seen by fluorescent immunostaining over DAPI-positive nuclei (fig. 1e, f). No expression of CaV1.2 α1-subunit-like immunoreactivity was seen in these astroglial cultures under all tested conditions (fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical characterization of primary murine astrocytes. GFAP staining revealed a moderate confluent layer of astrocytes, and some few highly positive reactive astrocytes (a, c). The staining for glutamine synthetase (GluS) showed a strong staining of astroglia all over the whole confluent layer (b). Nuclear DAPI (e, f) showed a confluent layer of cells. No immunostaining was evident for the CaV1.2 α1 channel (d). Scale bar = 20 μm (a, c–f), 10 μm (b).

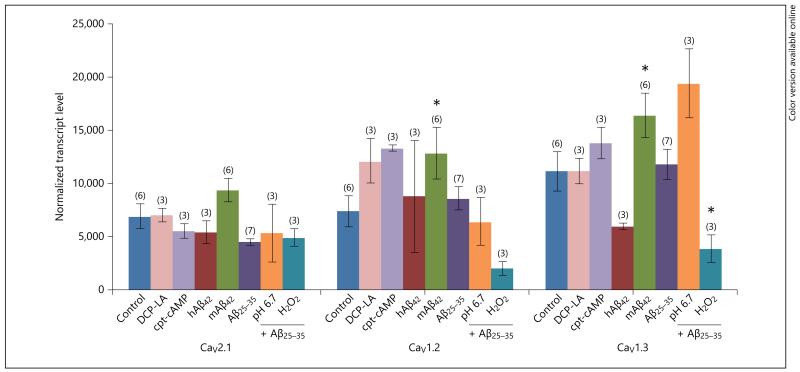

CaV1.2 α1-Subunit mRNA Expression after Three Days of Incubation

Neither the PKC-ε activator DCP-LA nor the cAMP agonist affected mRNA expression of α1-subunits (fig. 2). Human Aβ42 had no effect on mRNA expression, while murine Aβ42 slightly but significantly enhanced CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 α1-subunits (fig. 2). The toxic Aβ25–35 fragment had no effect on expression of any tested α1-subunits (fig. 2). However, CaV1.3 was significantly decreased when costimulated with the toxic Aβ25–35 fragment and H2O2 (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

qRT-PCR expression of CaV2.1, CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 in primary astrocytes after 3 days of incubation. Confluent astroglia was incubated without (Control) or with the PKC-ε activator DCP-LA or the cAMP agonist (cpt-cAMP) or with human or murine Aβ42 or the toxic fragment Aβ25–35 for 3 days. The toxic fragment was also coincubated under acidic conditions (pH 6.7) or with H2O2. After 3 days, cells of three 6-well dishes were scraped and pooled. After that, these cells were further processed for qRT-PCR. Values are given as means ± SEM normalized transcript level. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with a subsequent Fisher PLSD post hoc test. * p < 0.05.

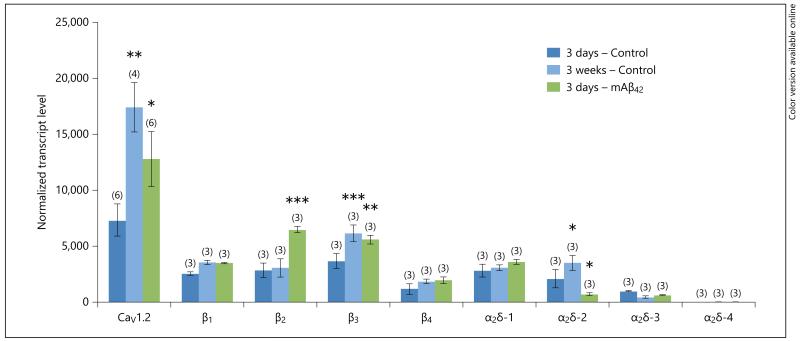

Expression of Auxiliary Subunits after Three Days

In order to test expression of all auxiliary subunits in the primary astrocytes, we focused on murine Aβ42, which had a significant effect on CaV1.2 subunit expression. Among all auxiliary subunits tested, only β2 and β3 were significantly enhanced, while the mRNA for α2δ-2 was significantly downregulated by murine Aβ42 (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

qRT-PCR expression of CaV1.2 and all auxiliary subunits (β1–4 and α2δ-1 to -4) in primary astrocytes. Confluent control (Control) astroglia was incubated without any exogenous stimulus for 3 days or 3 weeks. Furthermore, cells were treated with murine Aβ42 for 3 days. At the end of the experiment, cells of three 6-well dishes were scraped and pooled and further processed for RTPCR. Values are given as means ± SEM normalized transcript level. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with a subsequent Fisher PLSD post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

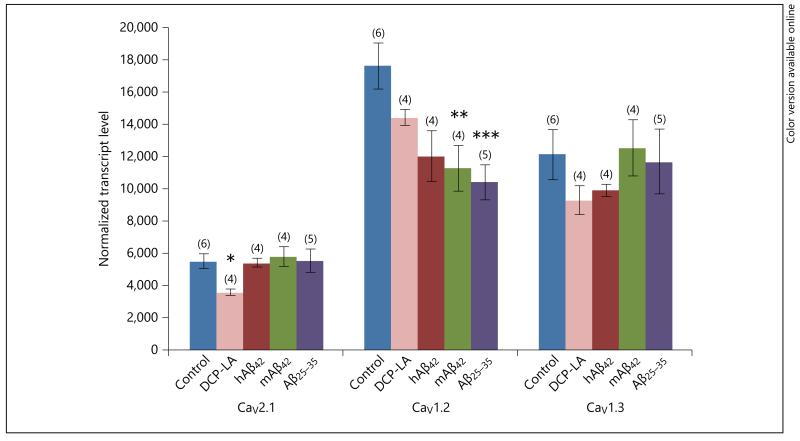

α1-Subunit mRNA Expression after Three Weeks of Incubation

A 3-week incubation of astroglia showed a significant increase for the mRNA of CaV1.2 α1 and β3 and α2 δ-2 compared with a 3-day control treatment (fig. 3). Surprisingly, a chronic treatment for 3 weeks with murine Aβ42 and the toxic fragment Aβ25–35 significantly decreased CaV1.2 α1-subunit expression, but not CaV2.1 and CaV1.3. The PKC-ε activator DCP-LA significantly decreased CaV2.1, but not CaV1.2 and CaV1.3, subunit expression in primary murine astroglia (fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR expression of CaV2.1, CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 in primary astrocytes after 3 weeks of incubation. Confluent astroglia was incubated without (Control) or with the PKC-ε activator DCP-LA or with human or murine Aβ or the toxic fragment Aβ25–35. After 3 weeks of incubation with reduced serum (1%), the cells of three 6-well dishes were scraped and pooled and further processed for qRT-PCR. Values are given as means ± SEM normalized transcript level. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with a subsequent Fisher PLSD post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Discussion

In the present study we found that Aβ peptides differentially regulate LTCC mRNA expression when incubated for a short (3 days) or long period (3 weeks).

Astroglial Cultures

It is assumed that astrocytes may contribute to several CNS pathologies, and reactive astrogliosis points to damaged tissue, which can easily be detected by GFAP staining, a reliable marker for activated astrocytes [9]. In addition, glutamine synthetase is another astroglia-specific staining. The primary astroglial culture model is well established in our research group [17, 18], displaying a confluent layer with some GFAP-positive reactive astroglia, and <1% of other cells. In order to culture astroglia for a longer time period, the cells are cultured with low serum to prevent overgrowth of the cells and subsequent cell death. In order to enhance astrogliosis, in some experiments the cells were incubated at a low pH (6.7) or together with hydrogen peroxide.

Effects of PKC-ε Activator and cAMP Agonist on LTCC Subunits

It has been reported that PKC-ε overexpression increases the mRNA levels of CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 α1-subunits in primary astrocytes [13]. In addition, a novel PKC-ε activator, DCP-LA, reduced Aβ levels [21], providing an important link to our Aβ experiments. Thus, as a control, we incubated our primary astrocytes with DCP-LA [21]. In fact, our data only showed a slight upregulation of the CaV1.2 subunit treated for 3 days with DCP-LA, while after 3 weeks, CaV2.1 was significantly downregulated. As another control, the effect of cAMP was tested, because it is well known that LTCC activity is regulated by cAMP production and subsequent activation of protein kinase A, involving β-adrenergic receptors [22, 23]. Further, increased cAMP levels in cultured astrocytes can convert flat polygonal astrocytes into process-bearing stellate astrocytes [24]. In order to increase intracellular cAMP, we used the highly membrane-permeable agonist cpt-cAMP. However, our data show that enhanced cAMP did not affect LTCC expression in primary astrocytes at all time points.

Effects of Acute (Three-Day) Aβ Treatment on α1-Subunits

We have recently shown that the CaV1.2 α1-subunit is highly expressed in GFAP-positive astrocytes surrounding Aβ plaques in an AD mouse model [16]. However, in this in vivo model, we cannot distinguish whether the peptides alone or the plaque per se may activate the calcium channels in these reactive astrocytes. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the mRNA expression levels of all LTCC subunits in primary astrocytes of postnatal mice. In the present study, we used 3 different Aβ peptides: human Aβ42, murine Aβ42 and a toxic Aβ25–35 amino acid fragment. We tested human and murine peptides because 3 amino acids are different between these two species [25] and it may be possible that human Aβ does not act on primary murine astrocytes. Aβ25–35 was used because this small fragment is the main toxic component of the Aβ peptide. Previous work has shown that Aβ25–35 induces cytoskeletal reorganization in cultured astrocytes [26] or revealed neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects on hippocampal neurons [27]. It was also suggested that this Aβ25–35 peptide destabilizes calcium homeostasis and renders human cortical neurons more vulnerable to excitotoxicity [28]. All peptides were used at a very high concentration of 10 μg/ml because it has been reported that primary astrocytes are markedly affected under these conditions [29, 30]. Our present data show that the addition of murine Aβ42 for 3 days slightly but significantly upregulated LTCC mRNA expression but not the protein of CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 in primary astrocytes. Thus, we conclude that an acute, brief exposure to Aβ does not markedly influence LTCC mRNA expression in cultured astrocytes.

Effects on Auxiliary Subunits and Potentiation of Astrogliosis

In order to test whether the Aβ peptide activates auxiliary subunits in vitro (independent of the α1-subunit), we performed a qRT-PCR analysis of all subunits. We could identify that β2 and β3 were upregulated but α2δ-2 was downregulated after incubation with murine Aβ42 for 3 days. This differential expression profile is difficult to explain, and still the signaling process in primary astrocytes is unknown. More experiments using electrophysiology with the patch clamp technique are required to further investigate this issue. In order to enhance the reactivity of primary astrocytes, we incubated the cells at a low pH (acidosis, pH 6.7) or treated the cells with a high concentration of hydrogen peroxide together with the toxic Aβ25–35 fragment. Indeed, chronic hypoxia dramatically increased the current density of membrane channel proteins in HEK 293 cells [31]. It has also been reported that Aβ induces cell death by generation of H2O2 [32]. However, costimulation with acidosis did not markedly affect mRNA expression of the LTCC subunits, while H2O2 led only to a slight decrease in expression, suggesting that, again, another more robust mechanism may account for the calcium channel activation.

Long-Time Exposure of Primary Astrocytes with Aβ

Thus, we hypothesized that in order to enhance LTCC expression, primary astrocytes must be exposed to Aβ peptides for a longer time period. In addition, the higher Aβ concentration and longer incubation over 3 weeks at 37°C would also likely induce aggregation of Aβ peptides and provide more plaque-promoting conditions. In order to decrease dramatic proliferation, the primary astrocytes were cultured under low-serum conditions together with the Aβ peptides for 3 weeks. Unexpectedly, we observed that the CaV1.2 mRNA were significantly downregulated and again no CaV1.2 α1 protein expression was seen. This suggests that neither soluble nor aggregated Aβ peptides alone are sufficient to induce a dramatic upregulation of the calcium channel in vitro. Thus, we conclude that more potent exogenous stimuli are necessary to activate calcium channels in reactive astrocytes in vitro, such as inflammation, oxidative stress and/or large Aβ plaques, or even an exposure for months. In fact, we have also shown in vivo that calcium channels are only upregulated at a very late stage (>11 months) in mice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data show that Aβ peptides differentially regulate LTCC mRNA expression in cultured primary cortical astrocytes when incubated for short and long periods. It seems likely that Aβ peptides alone are not sufficient to activate astroglial calcium channels. More robust long-lasting effects are necessary to activate Ca2+ expression in GFAP-positive astrocytes.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Ursula Kirzenberger-Winkler for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by the ‘Sonderforschungsbereich SFB F4405-B19 and F4406-B19’ of the Austrian Science Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Landfield PW. ‘Increased calcium-current’ hypothesis of brain aging. Neurobiol Aging. 1987;8:346–347. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(87)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khachaturian ZS. Hypothesis on the regulation of cytosol calcium concentration and the aging brain. Neurobiol Aging. 1987;8:345–346. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(87)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thibault O, Gant JC, Landfield PW. Expansion of the calcium hypothesis of brain aging in Alzheimer’s disease: minding the store. Aging Cell. 2007;6:307–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermair GJ, Flucher BE. Neuronal functions of auxiliary calcium channel subunits. In: Stephens G, Mochida S, editors. Modulation of Presynaptic Calcium Channels. Springer Science; Dordrecht: 2013. pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacVicar BA. Voltage-dependent calcium channels in glial cells. Science. 1984;226:1345–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.6095454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latour I, Hamid J, Beedle AM, Zamponi GW, MacVicar BA. Expression of voltage-gated Ca2+ channel subtypes in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2003;41:347–353. doi: 10.1002/glia.10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Ascenzo M, Vairano M, Andreassi C, Navarra P, Azzena GB, Grassi C. Electrophysiological and molecular evidence of L-(CaV1), N-(CaV2.2), and R-(CaV2.3) type Ca2+ channels in rat cortical astrocytes. Glia. 2004;45:354–363. doi: 10.1002/glia.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishiyama A, Yang Z, Butt A. Astrocytes and NG2-glia: what’s in a name? J Anat. 2005;207:687–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westenbroek RE, Bausch SB, Lin RCS, Franck JE, Noebels JL, Catterall WA. Upregulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in reactive astrocytes after brain injury, hypomyelination, and ischemia. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2321–2334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02321.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willis M, Kaufmann WA, Wietzorrek G, Hutter-Paier B, Moosmang S, Humpel C, Hofmann F, Windisch M, Knaus HG, Marksteiner J. L-type calcium channel CaV1.2 in transgenic mice overexpressing human AβPP751 with the London (V717I) and Swedish (K670M/N671L) mutations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:1167–1180. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgos M, Pastor MD, González JC, Martinez-Galan JR, Vaquero CF, Fradejas N, Benavides A, Hernández-Guijo JM, Tranque P, Calvo S. PKCε upregulates voltage-dependent calcium channels in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2007;55:1437–1448. doi: 10.1002/glia.20555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan E, Li B, Gu L, Hertz L, Peng L. Mechanisms for L-channel-mediated increase in [Ca2+]i and its reduction by anti-bipolar drugs in cultured astrocytes combined with its mRNA expression in freshly isolated cells support the importance of astrocytic L-channels. Cell Calcium. 2013;54:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacVicar BA, Hochman D, Delay MJ, Weiss S. Modulation of intracellular Ca++ in cultured astrocytes by influx through voltage-activated Ca++ channels. Glia. 1991;4:448–455. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daschil N, Obermair GJ, Flucher BE, Stefanova N, Hutter-Paier B, Windisch M, Humpel C, Marksteiner J. CaV1.2 calcium channel expression in reactive astrocytes is associated with the formation of amyloid-β plaques in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37:439–451. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser KV, Humpel C. Blood-derived serum albumin contributes to neurodegeneration via astroglial stress fiber formation. Pharmacology. 2007;80:286–292. doi: 10.1159/000106593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zassler Z, Blasig I, Humpel C. Protein delivery of caspase-3 induces cell death in malignant C6 glioma, primary astrocytes and immortalized and primary brain capillary endothelial cells. J Neurooncol. 2005;71:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-1364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlick B, Flucher BE, Obermair GJ. Voltage-activated calcium channel expression profiles in mouse brain and cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2010;167:786–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandesompele J, de Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, van Roy N, de Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson TJ, Cui C, Luo Y, Alkon DL. Reduction of β-amyloid levels by novel protein kinase Cε activators. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34514–34521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey RD, Hell JW. CaV1.2 signaling complexes in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;58:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall DD, Davare MA, Shi M, Allen ML, Weisenhaus M, McKnight GS, Hell JW. Critical role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring to the L-type calcium channel CaV1.2 via A-kinase anchor protein 150 in neurons. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1635–1646. doi: 10.1021/bi062217x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Won CL, Oh YS. cAMP-induced stellation in primary astrocyte cultures with regional heterogeneity. Brain Res. 2000;887:250–258. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02922-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada T, Sasaki H, Furuya H, Miyata T, Goto I, Sakaki Y. Complementary DNA for the mouse homolog of the human amyloid beta protein precursor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149:665–671. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salinero O, Moreno-Flores MT, Ceballos ML, Wandosell F. β-Amyloid peptide induced cytoskeletal reorganization in cultured astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250:279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattson MP, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. β-Amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1992;12:376–389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pentreath VW, Mead C. Responses of cultured astrocytes, C6 glioma and 1321NI astrocytoma cells to amyloid β-peptide fragments. Nonlinearity Biol Toxicol Med. 2004;2:45–63. doi: 10.1080/15401420490426990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Calcium signals induced by amyloid β peptide and their consequences in neurons and astrocytes in culture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1742:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scragg JL, Fearon IM, Boyle JP, Ball SG, Varadi G, Peers C. Alzheimer’s amyloid peptides mediate hypoxic up-regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels. FASEB J. 2005;19:150–152. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2659fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brera B, Serrano A, de Ceballos ML. β-Amyloid peptides are cytotoxic to astrocytes in culture: a role for oxidative stress. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:395–405. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]