Abstract

Background

Adjustment disorder with anxiety (ADWA) is a highly prevalent condition, particularly in primary care practice. There are relatively few systematic treatment trials in the area of ADWA, and there are few data on predictors of treatment response. Etifoxine is a promising agent insofar as it is not associated with dependence, but in primary care settings benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed for psychiatric symptoms. A randomized controlled trial of etifoxine versus alprazolam for ADWA was undertaken, focusing on efficacy and safety measures, and including an investigation of predictors of clinical response.

Methods

This was a comparative, multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial in two parallel groups of outpatients with ADWA. One group was treated with 150 mg/day for etifoxine, and the other with 1.5 mg/day for alprazolam for 28 days. Patients were followed for 4 weeks of treatment, and for an additional week after treatment discontinuation. The primary outcome measure was the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), while secondary outcome measures included the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), the Clinical Global Impressions-Change Scale (CGI-C), and the Self-Report for the Assessment of Adjustment Disorders. Non-inferiority analysis was used to assess the primary outcome measure, and a multivariate logistic regression was employed to investigate predictors of response.

Results

Two hundred and two adult outpatients with ADWA were enrolled at 17 primary care sites. One hundred and seventy seven patients completed the study (n = 87 in the etifoxine group; n = 90 in the alprazolam group). Etifoxine and alprazolam were accompanied by decreases in the HAM-A at day 28, with a difference between treatment groups in HAM-A score of 1.78 [90% CI; 0.23, 3.33] in favor of alprazolam. However, after medication discontinuation, HAM-A scores continued to improve in the etifoxine group, but increased in the alprazolam group; the difference between groups in mean change between day 28 and day 35 was significant (p = 0.019). Secondary outcome measures showed similar results for etifoxine and alprazolam at day 35. More treatment-related adverse events were reported in patients treated with alprazolam, particularly central nervous system-related AEs, and especially after medication discontinuation. No significant predictors of treatment response were found.

Conclusion

This randomized controlled trial provides support for the efficacy and safety of etifoxine in the management of adjustment disorder with anxiety, particularly when treatment discontinuation data are also assessed. Etifoxine has the important clinical advantage of having anxiolytic effects, which are not being associated with dependence. Pharmacotherapy was equally efficacious in patients with more severe anxiety symptoms at baseline. Additional work using longer-term follow-up and collecting data on cost-efficiency of management options would further advance the field of ADWA.

Funding

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were provided by Biocodex, Gentilly, France.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0176-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adjustment disorder with anxiety, Alprazolam, Etifoxine

Introduction

Adjustment disorders are characterized by the development of clinically significant emotional or behavioral symptoms in response to an identifiable stressor or stressors [1]. In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), adjustment disorders are categorized as trauma- and stressor-related disorders, alongside conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder [2]. Adjustment disorders are prevalent in the community, with point prevalence estimates ranging from 0.9% to 2.3% [3], and even higher in clinical samples, where point prevalence estimates range from 5% to 24%, with adjustment disorder with anxiety (ADWA) being the most frequent [4]. Adjustment disorders are associated with substantial morbidity and impaired quality of life [3, 5, 6].

Both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy of adjustment disorders have been investigated. A Cochrane review of interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders included nine studies of psychological interventions, and concluded that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) did not significantly reduce time until return to work, compared with no treatment [7]. There is also a small literature on the investigation of antidepressants and benzodiazepines for adjustment disorder; to date, however, no agent has been registered for this indication [3]. In clinical practice, benzodiazepines are very often prescribed [8], even though concerns have been raised about the adverse event profile of these agents, including cognitive dysfunction and the potential risk for dependence [9].

Etifoxine is a benzoxazin drug that does not belong to the benzodiazepine family, but that nevertheless has anxiolytic properties [10]. Etifoxine directly interacts with the chloride channel of the GABAA receptor complex and therefore potentiates GABAergic synaptic transmission [11–13]. Further, etifoxine may have indirect effects, acting at peripheral benzodiazepine receptors (PBR) to increase brain neurosteroids (pregnenolone, allopregnanolone) with anti-anxiety effects [14, 15]. Previous trials have found that etifoxine has similar efficacy compared to buspirone [16] and to lorazepam [17] in ADWA. Furthermore, etifoxine has few adverse cognitive or psychomotor effects and is not associated with dependence [18].

The objective of the present study was to compare the efficacy and safety of etifoxine with the high potency benzodiazepine, alprazolam, in the treatment of ADWA, and to evaluate the persistence of clinical effects as well as any rebound effects after treatment discontinuation. The tertiary outcome was to determine the predictors of pharmacotherapy response in ADWA.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This prospective study was conducted in South Africa as a comparative, multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial in two parallel groups of outpatients with ADWA. Seventeen centres in two locations (Cape Town, Johannesburg) participated. A non-inferiority design comparing etifoxine with a commonly prescribed anxiolytic agent rather than with a placebo was chosen, and attention was paid to the visit after treatment discontinuation. Exploratory analyses of socio-demographic and clinical predictors of scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), the primary outcome measure, were also undertaken to determine the predictors of pharmacotherapy response in ADWA.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Before starting the trial, all investigators (n = 35) were trained by the study coordinator to diagnose ADWA. The full day of training included viewing videos of clinical cases, training in ADWA diagnosis, and training in study symptom scales. After the inclusion visit, participants attended three visits: after 1 week of treatment (day 7), at the end of the treatment period (day 28) and 1 week after treatment discontinuation (day 35). Efficacy and safety measures were undertaken at each of these visits.

ADWA patients included in the study were randomly assigned to receive etifoxine or alprazolam per os. A randomization list was established and study treatments were assigned by each investigator in ascending order of numbering based on the chronological enrollment order. Study drug was to be taken daily for 28 days (one capsule in the morning, at noon and in the evening), at usual dosages (150 mg/day for etifoxine, and 1.5 mg/day for alprazolam), in conformity with the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) of the two drugs. Study treatments were presented as capsules identical in their appearance.

Patients

To be eligible for inclusion, male or female outpatients aged 18–65 years had to meet the criteria for ADWA as defined by the DSM-IV [19]. In addition, baseline score on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) [20] was ≥20, with a baseline score in at least one of three subscales (work, family and social life) of the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) [21] ≥5, and a baseline score on the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [22] <20.

Participants had no comorbid psychiatric or substance use disorder (as assessed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [23]), no suicidal thoughts, present or past history of epilepsy, no medical disorder physiologically responsible for anxiety, and were not pregnant nor breast feeding. Current or past (previous month) treatment with benzodiazepines or other psychotropic agents (including alternative medicines) was not allowed. Current treatment with drugs likely to interfere with the metabolism of the study treatments was also an exclusion criterion.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

To assess the primary outcome measure, the HAM-A Scale was employed on day 7, day 28, and day 35. To assess the secondary outcome, the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) [24], the SDS, and the Self-Report for the Assessment of Adjustment Disorders [25] were also administered at these study visits. The MADRS was also administered at baseline.

The Self-Report for the Assessment of Adjustment Disorders is composed of 29 items, measuring the reactions triggered by the stressful event. Each item was rated from 1 (never) to 4 (often), resulting in six sub-scores, namely intrusions, avoidance, failure to adapt, depressive mood, anxiety and impulse disturbance [26]. This was the first use of the scale in a clinical trial; the results collected and the validity of the scale will be more fully described in a separate article.

All adverse events were recorded at each study visit and relationship to treatment was rated according to the investigator’s judgment. On day 35, withdrawal symptoms were assessed with the Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) Scale [27].

Statistical Analyses

Sample size was determined to achieve 80% power to detect a difference inferior to 2.5 points in HAM-A total score on day 28 between the two groups. The non-inferiority of etifoxine compared to alprazolam would be demonstrated if the upper limit of the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the difference ‘etifoxine minus alprazolam’ was lower than 2.5 (primary efficacy analysis). The 2.5 cutoff was chosen in accordance with data from two previous studies of etifoxine in ADWA [16, 17] as well as previous clinical trials using the HAM-A [28, 29].

All patients who received at least one dose of study drug comprised the safety set. All randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug with at least one endpoint assessed comprised the full analysis set (FAS).

HAM-A total score was analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for baseline score. Responder status (as assessed by ≥50% decrease in HAM-A) was compared between groups using a Chi-square test. Other secondary outcome measures, including HAM-A psychic and somatic sub-scores, were compared between treatment groups using an ANCOVA or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with significance level set at 0.05. These analyses were conducted with SAS® software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, North Carolina).

Socio-demographic and clinical variables, including stressor type, potentially predicting clinical response on day 28 and day 35 were entered into univariate logistic regressions with the response on HAM-A Scale as the dependent variable. Factors showing a p value less than or equal to 0.10, and that were not significantly associated with one another, were then entered into a multivariate model using forward selection, again using SAS®.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Data

Between October 2011 and January 2013, 202 participants who had consulted their primary practitioner for symptoms of ADWA were included in the study. One patient, who signed the informed consent but did not fully perform the day 1 visit, was not randomized and was excluded from all analysis populations. Overall, 201 patients received at least one dose of the study treatments (safety set): 100 received etifoxine and 101 received alprazolam.

The baseline characteristics of the 201 patients from the safety set are presented in Table 1. At inclusion, the two groups were similar regarding nearly all the variables assessed, with a mean age of 39.4 years (range 18–64). The percentage of female patients was slightly higher in the etifoxine group: 76.0% vs. 70.3% in the alprazolam group. The mean weight of etifoxine patients was somewhat higher than alprazolam patients (80.7 and 76.4 kg, respectively), resulting in a higher body mass index in the etifoxine group (29.1 vs. 26.8 kg m−2).

Table 1.

Patients baseline characteristics (safety set)

| Etifoxine (n = 100) | Alprazolam (n = 101) | Total (n = 201) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 76.0 | 70.3 | 73.1 |

| Age; mean (SD) [min–max] | 40.0 (11.8) [18–62] | 38.9 (12.8) [18–64] | 39.4 (12.3) [18–64] |

| Weight; mean (SD) [min–max] | 80.7 (19.4) [50–133] | 76.4 (18.4) [46–133] | 78.5 (19.0) [46–133] |

| Main stressor (%) | |||

| Family/love life | 39.0 | 38.6 | 38.8 |

| Work/school | 34.0 | 41.6 | 37.8 |

| Finance | 12.0 | 12.9 | 12.4 |

| Other | 15.0 | 6.9 | 10.9 |

| HAM-A total score; mean (SD) [min–max] | 29.3 (5.9) [20–46] | 30.5 (7.2) [20–55] | 29.9 (6.6) [20–55] |

| MADRS score; mean (SD) | 12.4 (4.3) | 12.4 (4.9) | 12.4 (4.6) |

| CGI severity score; mean (SD) | 3.9 (1.0) (n = 98) | 3.8 (1.1) (n = 98) | 3.8 (1.0) (n = 196) |

| SDS scores; mean (SD) | |||

| Work/schoola | 5.5 (2.2) (n = 84) | 6.3 (2.0) (n = 84) | 5.9 (2.1) (n = 168) |

| Social life | 5.9 (2.5) | 6.3 (2.0) | 6.1 (2.3) |

| Family life | 5.8 (2.3) | 6.2 (2.3) | 6.0 (2.3) |

CGI Clinical Global Impression Scale, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, MADRS Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, SD standard deviation, SDS Sheehan Disability Scale

aSubgroup of patients who worked/studied during the week preceding the study entry

The main stressor responsible for the present episode of ADWA was related to family/love life (38.8% of patients), work/school (37.8%), finance (12.4%), or other issues (10.9%). The mean HAM-A total score at baseline was 29.9 (range 20–55), the mean (±standard deviation [SD]) CGI severity score was 3.8 (±1.0), with mean scores of 6 on the SDS subscales, reflecting the presence of illness that moderately disrupted the patients’ work, social life and family life. Mean (±SD) score on the MADRS was 12.4 (±4.6), indicative of low depressive symptoms.

Patient Disposition

Thirteen patients from the etifoxine group (13.0%) and 11 from the alprazolam group (10.9%) prematurely discontinued the study, mainly for adverse events (etifoxine: 4, alprazolam: 6) and consent withdrawal (etifoxine: 3, alprazolam: 2). Overall, 177 patients completed the study, 87 in the etifoxine group (87.0%) and 90 in the alprazolam group (89.1%). The mean (±SD) treatment duration was 26.6 ± 6.9 days in the etifoxine group (n = 99) and 27.3 ± 6.0 days in the alprazolam group (n = 99). Based on pill count, mean compliance rates with treatment were 97.2% in the etifoxine group (n = 98) and 98.5% in the alprazolam group (n = 98).

Efficacy Analysis

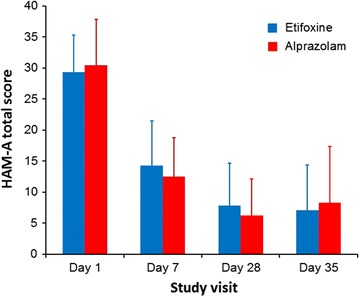

The FAS comprised 190 patients: 95 in etifoxine group and 95 in alprazolam group. Improvement of anxiety symptoms on day 28 was demonstrated in both groups, as reflected by a mean decrease in the HAM-A total score of 72.5% ± 23.8% and 79.7% ± 17.0% in the etifoxine and alprazolam groups, respectively (Fig. 1). The adjusted mean difference in HAM-A score of 1.78 [90% CI; 0.23, 3.33] was in favor of alprazolam, and as the upper limit of the 90% CI was greater than the 2.5 reference value, the non-inferiority of etifoxine compared with alprazolam was not shown (Table 2). On secondary outcome measures, there were no significant differences between the two groups at day 28 in the Self-Rated Assessment of ADWA symptoms, CGI scores, responder status, HAM-A psychic score, or SDS (Table 2) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Progression of the mean (SD) HAM-A total score during the study (FAS). FAS Full analysis set, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Mean HAM-A scores adjusted for day 1 value (±SE) and percentage of responders during the study (FAS)

| Etifoxine (n = 95) | Alprazolam (n = 95) | |

|---|---|---|

| Raw mean HAM-A score on day 1 (±SD) | 29.3 (6.0) | 30.4 (7.4) |

| Adjusted mean HAM-A score on day 7 (±SE) | 14.49 (0.64) | 12.29 (0.64) |

| Adjusted mean difference (±SE) − [90% CI] | 2.19 (0.91) − [0.69 to 3.70] | |

| Adjusted mean HAM-A score on day 28 (±SE) | 7.95 (0.66) (n = 90) | 6.17 (0.66) (n = 91) |

| Adjusted mean difference (±SE) − [90% CI] | 1.78 (0.94) − [0.23 to 3.33] | |

| Adjusted mean HAM-A score on day 35 (±SE) | 7.24 (0.87) (n = 87) | 8.17 (0.86) (n = 90) |

| Adjusted mean difference (±SE) − [90% CI] | −0.93 (1.23) − [−2.96 to 1.10] | |

| Respondersa/remittersb (%) | ||

| Day 7 | 52.6/17.9 (n = 95) | 65.3/21.1 (n = 95) |

| Day 28 | 85.6/55.6 (n = 90) | 92.3/67.0 (n = 91) |

| Day 35 | 80.5/64.4 (n = 87) | 75.6/58.9 (n = 90) |

CI confidence interval, FAS full analysis set, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, SD standard deviation, SE standard error

aPatients with a decrease from baseline in the HAM-A total score ≥50%

bPatients with a HAM-A total score ≤7

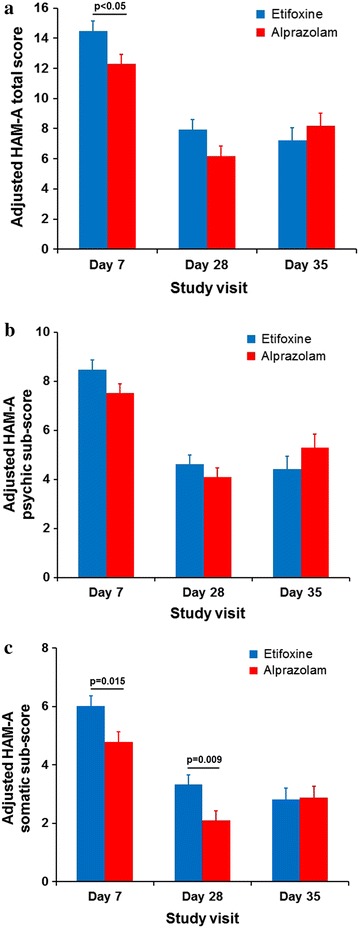

Fig. 3.

a Progression of the mean HAM-A total score during the study, b progression of the HAM-A psychic sub-score and c progress of the HAM-A somatic sub-score adjusted for day 1 value (+SE) during the study (FAS). p values indicate significant scores. FAS full analysis set, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, SE standard error

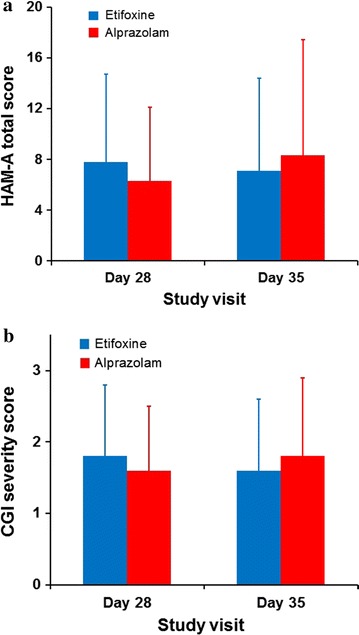

The benefits of treatment appeared from the first week with a mean decrease in the HAM-A score of 51.2% ± 22.5% and 58.7% ± 18.9% in the etifoxine and alprazolam groups, respectively, on day 7. There was an adjusted mean difference in HAM-A score of 2.19 [90% CI; 0.69, 3.70] and [95% CI; 0.40, 3.99] statistically significant in favor of alprazolam. However, 1 week after treatment discontinuation, HAM-A in the etifoxine group continued to decrease (−0.6 ± 4.5), while HAM-A in the alprazolam group increased (+2.2 ± 7.0) (p = 0.019) (Fig. 2). Thus, there was an adjusted mean difference in HAM-A score of −0.93 [90% CI; −2.96, 1.10] in favor of etifoxine, demonstrating non-inferiority of etifoxine compared with alprazolam at day 35 (Table 2). Similarly, on secondary outcome measures, there were no significant differences between groups at day 35 after treatment discontinuation, although scores numerically favored etifoxine at the later time point (Table 2) (Fig. 3). For example, CGI severity score decreased between day 28 and day 35 in the etifoxine group (−0.2 ± 0.8), while it increased in the alprazolam group (+0.2 ± 1.0), resulting in a significant difference between groups in the score change from day 28 to day 35 (p = 0.004).

Fig. 2.

a Mean (SD) HAM-A total score and b CGI severity score at day 28 and day 35 (FAS). CGI Clinical Global Impression, FAS full analysis set; HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, SD standard deviation

Adverse Events

Adverse events were analyzed on the safety set (n = 201 patients). During the study, 35 patients (35.0%) in the etifoxine group experienced at least one adverse event compared to 48 (47.5%) in the alprazolam group (Table 3). During the treatment period (day 1–day 28), 35 patients (35.0%) experienced 70 adverse events in the etifoxine group compared to 44 patients (43.6%) who had 61 adverse events in the alprazolam group (p = 0.214). Adverse events were, however, markedly more often rated as “treatment-related” by the investigators in the alprazolam group (62.3%; 13 “possibly” and 25 “probably” related) than in the etifoxine group (34.3%; 13 “possibly” and 11 “probably” related) (p = 0.002).

Table 3.

Safety results (safety set)

| Etifoxine (n = 100) | Alprazolam (n = 101) | p value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events | Number (%) of patients | Number of events | Number (%) of patients | ||

| Adverse events | 74 | 35 (35.0) | 77 | 48 (47.5) | |

| Serious adverse events | 2 | 2 (2.0) | 2 | 2 (2.0) | |

| Treatment-emergent adverse eventsa | 70 | 35 (35.0) | 61 | 44 (43.6) | 0.214 |

| Post-treatment adverse eventsb | 4 | 4 (4.0) | 16 | 11 (10.9) | 0.063 |

| Increase in HAM-A total score ≥5 between day 28 and day 35 | 11 (12.6) n = 87 | 21 (23.3) n = 90 | 0.065 | ||

HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

* Comparison of % of patients

aEvents that started during treatment period, between day 1 and day 28

bEvents that started after treatment stop, between day 28 and day 35

Adverse events resulted in treatment withdrawal in 7 patients from the etifoxine group and 6 patients from the alprazolam group, mainly due to central nervous system (CNS) and gastrointestinal symptoms. Indeed, CNS symptoms were the most frequent adverse events and were reported by 16.0% and 24.8% of the patients in the etifoxine and alprazolam group, respectively. Notably, many more patients reported episodes of “somnolence” or “sedation” in the alprazolam group (14 patients) than in the etifoxine group (4 patients). Additionally, “fatigue” events were only observed in patients who received alprazolam (4 patients). Gastrointestinal symptoms were also quite frequent and were reported by 12 patients in the etifoxine group and 8 in the alprazolam group. These various differences did not, however, reach statistical significance.

Four serious adverse events were reported by four patients (two in each group). In the etifoxine group, one patient underwent an arthroscopy consequent to a knee ligament injury and a second patient had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy to treat an episode of gallstone cholecystitis. Relationship with study treatment was judged by investigators “unrelated” and “unknown”, respectively. In the alprazolam group, one patient had suicidal ideation and was diagnosed with temporal lobe epilepsy, while a second one took an overdose of study treatment. Investigators considered the relationship with study treatment “unlikely” and “possible”, respectively for these events.

On day 35, the mean total DESS score was similar in the etifoxine and the alprazolam groups, with values of 2.0 (±4.4) and 3.0 (±5.4), respectively. After treatment discontinuation, notably more patients (11%) experienced adverse events in the alprazolam group (16 events) than in the etifoxine group (4% and 4 events) (p = 0.063). Among these adverse events, 50% were treatment-related in the alprazolam group (5 “possible” and 3 “probable”) compared to none in the etifoxine group.

Predictor Analyses

Univariate analyses indicated that women responded better to treatment (p = 0.045 at day 28, p = 0.017 at day 35), and that patients with high MADRS baseline scores responded worse to treatment (p = 0.025) at day 35. However, there was no significant link between response to treatment and the treatment administered (alprazolam or etifoxine), HAM-A baseline score, or other socio-demographic and clinical variables at these time points. Furthermore, on multivariate analysis, there were no significant predictors of treatment response.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that (1) HAM-A scores favored alprazolam compared to etifoxine at day 7 and at day 28, with significant differences at day 7 and non-inferiority of etifoxine unable to be demonstrated at day 28, (2) HAM-A scores slightly favored etifoxine compared to alprazolam after treatment discontinuation, with a significant difference in HAM-A score change apparent during this last week of the study, (3) there were more adverse events in the alprazolam group, particularly central nervous system-related AEs, and especially after medication discontinuation, and (4) no significant predictors of treatment response were found.

The efficacy of alprazolam in ADWA is consistent with prior findings that benzodiazepines are efficacious in the treatment of this condition. The early onset of action of alprazolam is also consistent with knowledge of the pharmacology of this agent [9]. The finding that alprazolam may be particularly effective for somatic symptoms of anxiety (Fig. 3) is similarly consistent with earlier work [30]. Although the cutoff of 2.5 for demonstrating the non-inferiority was based on prior work, it is relevant to emphasize that this is not universally agreed upon figure; a more conservative cutoff of 4 has been used in work comparing venlafaxine to placebo for anxiety disorders [31]. Furthermore, ongoing caution is warranted given the lack of placebo-controlled data showing the efficacy of benzodiazepines in ADWA [32], and concerns about the potential for dependence [9].

The efficacy of etifoxine in ADWA is also consistent with prior findings, which have indicated non-inferiority for this agent compared with buspirone [16] and lorazepam [17], using a design very similar to the current one. In those prior studies, when compared to buspirone or lorazepam, more patients were responders or clinical improvement was better on the primary outcome analysis with etifoxine, there was no difference in speed of onset, and anxiety rebound was greater with lorazepam than etifoxine. Secondary outcome measures in the current study support the early efficacy of etifoxine, and the predictor analysis failed to find a relationship between treatment type (alprazolam or etifoxine) and response to treatment at day 28. More importantly, while HAM-A and CGI scores decreased after treatment discontinuation in the etifoxine group, they increased in the alprazolam group, with a significant difference between groups in change between day 28 and day 35.

The safety profile of etifoxine and alprazolam is again consistent with prior work on these agents [17]. Thus, it is notable that treatment-emergent adverse events were more likely to occur in the alprazolam group, and these were significantly more likely to be considered treatment-related by clinicians. Furthermore, more CNS-related adverse events, such as somnolence or sedation, were reported in the alprazolam group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. Finally, the higher proportion of patients with adverse events in the alprazolam group was particularly apparent after treatment discontinuation. These findings are consistent with consensus statements that highlight cognitive adverse events and the potential for dependence with benzodiazepines [9]. In contrast, etifoxine has a relatively safe adverse event profile, and has the significant clinical advantage of having anxiolytic properties, while not being associated with potential for dependence.

In general, it may be pointed out that much remains to be learned about the treatment of ADWA. The predictor analysis provided here showed no significant predictors of clinical response, indicating that drug treatment may be useful in both less and more severe anxiety. With a larger sample size, depression scores may have significantly predicted worse response, and certainly antidepressants may be considered in anxious patients with an elevated MADRS score. There is also a significant need for cost-efficiency data and for long-term follow-up. In the interim, however, the current data support the efficacy and safety of etifoxine in the treatment of ADWA. While benzodiazepines such as alprazolam may also be reasonable to consider, etifoxine was associated with fewer CNS-related adverse effects, and no rebound effect after treatment discontinuation, and therefore is an important alternative approach for the management of ADWA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were provided by Biocodex, Gentilly, France. The author meets the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Prof Stein is supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa. In the past 3 years, Prof. Stein has received research Grants and/or consultancy honoraria from AMBRF, Biocodex, Cipla, Lundbeck, National Responsible Gambling Foundation, Novartis, Servier, and Sun.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1980.

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- 3.Casey P. Adjustment disorder: new developments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(6):451. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jäger M, Frash K, Becker T. Adjustment disorders—nosological state and treatment options. Psychiatr Prax. 2008;35:219–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-986289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, Endicott J. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1171–1178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carta MG, Balestrieri M, Murru A, Hardoy MC. Adjustment disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arends I, Bruinvels DJ, Rebergen DS, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Madan I, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Bültmann U, Verbeek JH. Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Esposito E, Barbui C, Patten SB. Patterns of benzodiazepine use in a Canadian population sample. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin DS, Aitchison K, Bateson A, Curran HV, Davies S, Leonard B, Nutt DJ, Stephens DN, Wilson S. Benzodiazepines: risks and benefits. A reconsideration. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(11):967–971. doi: 10.1177/0269881113503509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verleye M, Schlichter R, Gillardin JM. Interactions of etifoxine with the chloride channel coupled to the GABAA receptor complex. NeuroReport. 1999;10:3207–3210. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199910190-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlichter R, Rybalchenko V, Poisbeau P, Verleye M, Gillardin JM. Modulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission by the non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic etifoxine. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1523–1535. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verleye M, Pansart Y, Gillardin JM. Effects of etifoxine on ligand binding to GABAA receptors in rodents. Neurosci Res. 2002;44:167–172. doi: 10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamon A, Morel A, Hue B, Verleye M, Gillardin JM. The modulatory effects of the anxiolytic etifoxine on GABAA receptors are mediated by the β subunit. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:293–303. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(03)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verleye M, Akwa Y, Liere P, Ladurelle N, Pianos A, Eychenne B, Schumacher M, Gillardin JM. The anxiolytic etifoxine activates the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor and increases the neurosteroid levels in rat brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:712–720. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugale RR, Sharma AN, Kokare DM, Kokare DM, Hirani K, Subhedar NK, Chopde CT. Neurosteroid allopregnanolone mediates anxiolytic effect of etifoxine in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1184:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Servant D, Graziani PL, Moyse D, Parquet PJ. Treatment of adjustment with anxiety: efficacy and safety of etifoxine in a double-blind controlled study. Encephale. 1998;24:569–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen N, Fakra E, Pradel V, Jouve E, Alquier C, Le Guern ME, Micallef J, Blin O. Efficacy of etifoxine compared to lorazepam monotherapy in the treatment of patients with adjustment disorders with anxiety: a double-blind controlled study in general practice. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:139–149. doi: 10.1002/hup.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Micallef J, Soubrouillard C, Guet F, Le Guern ME, Alquier C, Bruguerolle B, Blin O. A double blind parallel group placebo controlled comparison of sedative and amnesic effects of etifoxine and lorazepam in healthy subjects. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2001;15:209–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2001.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1994.

- 20.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guy W. Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health-US Dept of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM); 1976, pp. 76–338.

- 25.Maercker A, Einsle F, Köllner V. Adjustment disorders as stress response syndromes: a new diagnostic concept and its exploration in a medical sample. Psychopathology. 2007;40:135–146. doi: 10.1159/000099290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Einsle F, Köllner V, Dannemann S, Maercker A. Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:584–595. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.487107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, Ascroft RC, Krebs WB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(2):77–87. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rickels K, Schweizer E, DeMartinis N, Mandos L, Mercer C. Gepirone and diazepam in generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:272–277. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199708000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn JB, Wilcox CS. Low-sedation potential of buspirone compared with alprazolam and lorazepam in the treatment of anxious patients: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1986;47(986):409–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickels K, Downing R, Schweizer E, Hassman H. Antidepressants for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine, trazodone, and diazepam. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:884–895. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230054005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelenberg AJ, Lydiard RB, Rudolph RL, Aguiar L, Haskins JT, Salinas E. Efficacy of venlafaxine extended-release capsules in nondepressed outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(23):3082–3088. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Leo D. Treatment of adjustment disorders: a comparative evaluation. Psychol Rep. 1989;64(1):51–54. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.64.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.