ABSTRACT

Nuclear functions including gene expression, DNA replication and genome maintenance intimately rely on dynamic changes in chromatin organization. The movements of chromatin fibers might play important roles in the regulation of these fundamental processes, yet the mechanisms controlling chromatin mobility are poorly understood owing to methodological limitations for the assessment of chromatin movements. Here, we present a facile and quantitative technique that relies on photoactivation of GFP-tagged histones and paired-particle tracking to measure chromatin mobility in live cells. We validate the method by comparing live cells to ATP-depleted cells and show that chromatin movements in mammalian cells are predominantly energy dependent. We also find that chromatin diffusion decreases in response to DNA breaks induced by a genotoxic drug or by the ISceI meganuclease. Timecourse analysis after cell exposure to ionizing radiation indicates that the decrease in chromatin mobility is transient and precedes subsequent increased mobility. Future applications of the method in the DNA repair field and beyond are discussed.

KEY WORDS: Chromatin mobility, Paired-particle tracking, DNA damage

INTRODUCTION

In eukaryotes, DNA is wrapped around histone proteins in a complex structure, the chromatin. Higher-order organization of the chromatin exerts an important influence on genomic functions, including gene expression, DNA synthesis and DNA repair. It is tightly controlled and constantly remodeled during cell differentiation, cell division and in response to DNA damage (Abad et al., 2007; Chandramouly et al., 2007; Goldberg et al., 2007; Misteli and Soutoglou, 2009; Soria et al., 2012; Vidi et al., 2012; Seeber et al., 2013). Covalent histone and DNA modifications largely determine chromatin compaction. Much less is known regarding the kinetics of chromatin in different contexts, notably during the DNA damage response (DDR), where this aspect of nuclear architecture appears to play a particularly important role (Misteli and Soutoglou, 2009). One bottleneck for studying this aspect is the scarcity of methods suitable to quantify chromatin movements.

Particle-tracking toolkits are well suited to measure the dynamics of macromolecules with slow diffusion in a confined medium such as chromatin (Marshall et al., 1997; Heun et al., 2001; Vazquez et al., 2001; Neumann et al., 2012; Miyanari et al., 2013). With single-particle tracking (SPT) approaches, time-lapse images are registered to compensate for cellular movements, often using the center of the nucleus, the nuclear envelope or nuclear bodies as offsets. Registration, however, adds uncertainties to the measurements, because cell nuclei rotate and distort (Kumar et al., 2014). Alternatively, it is possible using paired-particle tracking (PPT) to convert molecular dynamics from two-dimensional (2D) imaging planes into 1D motions that do not depend on cell movements (Heun et al., 2001; Vazquez et al., 2001). Here, mean squared displacements (MSD) and the corresponding diffusion coefficients are calculated from variations in the distance between two particles.

Studies on chromatin dynamics often rely on Lac arrays stably integrated at specific loci and visualized with fluorescent proteins (Marshall et al., 1997; Chubb et al., 2002; Dion and Gasser, 2013; Miné-Hattab and Rothstein, 2013). Some cell types such as stem or primary cells, however, cannot easily be engineered with DNA arrays and one cannot exclude that large insertions of repetitive ectopic DNA might alter chromatin behavior. In addition, although integrated arrays provide locus-specific information (Chubb et al., 2002), it is difficult to infer an overall picture of chromatin dynamics in the cell nucleus from these measurements. Conversely, labeling of histone proteins fused to photoactivatable GFP (PAGFP) provides locus-independent information on global chromatin dynamics with spatiotemporal resolution (Kruhlak et al., 2006; Wiesmeijer et al., 2008). Here, we describe a methodology to quantify the mobility of native chromatin in live cells. The novelty of the approach is to integrate PPT and nucleosomal tag photoactivation, which circumvents the need for image registration. Analysis after DNA double-strand break (DSB) induction indicates altered mobility in response to DNA damage.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

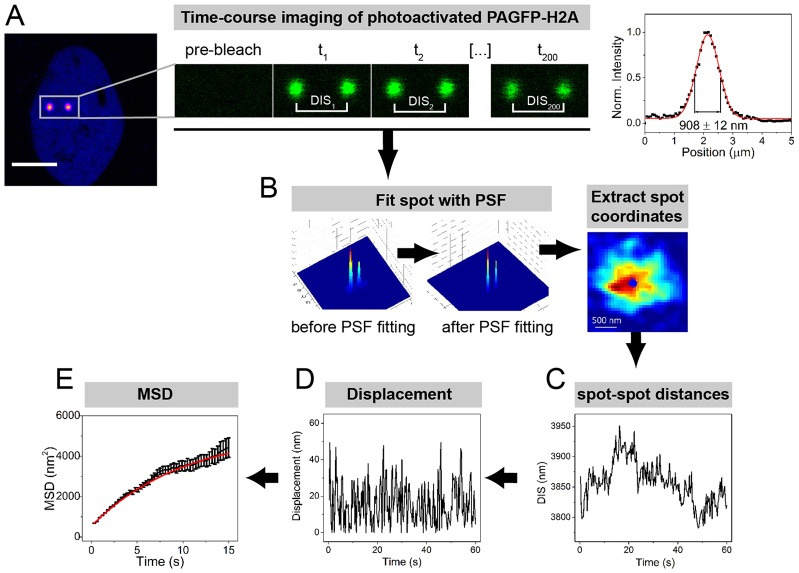

To measure chromatin dynamics in live cells, we developed a method based on chromatin labeling with PAGFP fused to the core histone H2A. Tandems of photoactivated PAGFP–H2A spots were imaged at high frequency and diffusion coefficients were calculated using a particle-tracking algorithm (Fig. 1; supplementary material Fig. S1A; Movie 1). As illustrated in Fig. 1C, the photoactivated spots had confined movements within the imaging period. The amplitudes of these movements were smaller than the diffraction limit and could therefore not be resolved by conventional optical approaches. After fitting with a point-spread function (PSF), the positions of the spots could be determined with 1 nm accuracy (Yildiz et al., 2003) and the distances between spots (DIS) were followed over 1-minute timecourses. DIS values were used to compute the MSD from which diffusion coefficients were calculated (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the PAGFP-PPT measurements. (A) Representative confocal images of PAGFP–H2A before and after GFP photoactivation. The plot on the right represents a cross-section of the spot intensity. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Illustration of the PSF used for fitting confocal images. The 3D profile is depicted (left). After the PSF fitting, a smooth 3D Gaussian profile is obtained (middle), enabling precise localization of the spot coordinates (right). (C) Example of timecourse distribution of spot-to-spot distance (DIS) calculated from the localization analysis. (D) Timecourse displacement of the spot-to-spot distances. (E) MSD curve representing chromatin dynamics. Data show the mean±s.e.m.

The PAGFP-PPT approach minimized the influence of cell motion on diffusion measurements. PPT MSD curves had plateau shapes characteristic of constrained random walk expected for chromatin (Dion and Gasser, 2013). In contrast, SPT curves had exponential shapes characteristic of directional cellular motions (supplementary material Fig. S1B–D). To ensure that the 405-nm laser pulses used to photoactivate PAGPF–H2A did not induce DNA breaks, we used the DNA clamp PCNA as a marker for UV-induced DNA damage (supplementary material Fig. S2A). Under the conditions used for PAGFP–H2A photoactivation and tracking, RFP–PCNA did not accumulate at the photoactivated spots. However and as expected, we detected focal PCNA recruitment in cells sensitized with BrdU (Mortusewicz et al., 2006). We also determined that MSD values were not influenced by the intensity of the photoactivated spots, i.e. by PAGFP–H2A expression levels that might vary across treatments (supplementary material Fig. S2B).

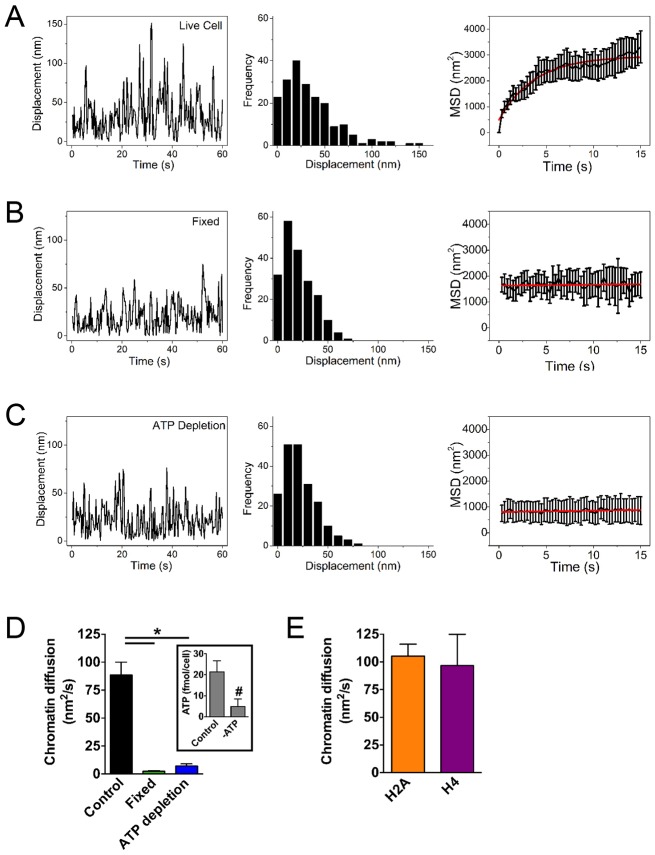

For validation, we compared chromatin diffusion in live and in fixed cells (Fig. 2 and supplementary material Movies 1 and 2). In untreated cells, the average diffusion time was 99±11 nm2/s, similar to previous reports (Dion and Gasser, 2013; Miné-Hattab and Rothstein, 2013). Fixation with formaldehyde reduced diffusion by >30-fold, indicating a modest contribution of noise to the measurements (Fig. 2A,B,D). ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes constantly modify nucleosome positioning (Wang et al., 2007; Erdel et al., 2010; Narlikar et al., 2013) and, as expected, cells incubated with deoxyglucose and sodium azide (to inhibit ATP synthesis by glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, respectively) had significantly decreased chromatin diffusion (Fig. 2A,C,D), in line with previous work (Weber et al., 2012). We measured similar chromatin diffusion coefficients in cells expressing PAGFP–H2A and in cells expressing the histone H4 fused to PAGPF, indicating that the method is not influenced by histone-specific characteristics (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Cell fixation and ATP depletion reduce chromatin diffusion. PAGFP–H2A PPT in live untreated cells (A), in cells fixed with formaldehyde (B) or after ATP depletion (C). Representative traces of displacements are shown (left) with the corresponding frequency distribution plots (center). MSD traces (right) were used to calculate chromatin diffusion. MSD data in A–C show the mean±s.e.m. (D) Quantification of chromatin diffusion in untreated, fixed or ATP-depleted cells. Data show the mean±s.e.m (from 10–20 cells); *P<0.0001 (Tukey test). The inset shows ATP levels in control and ATP-depleted cells. Data show the mean±s.e.m. (three biological replicates analyzed in triplicate); #P<0.0001 (Student's t-test). (E) Chromatin diffusion calculated with cells expressing PAGFP–H2A or PAGFP–H4 (n≧10). Data show the mean±s.e.m.

Next, the PAGFP-PPT method was applied to measure chromatin mobility in response to DNA damage. Cells were treated with bleomycin (BLM) at a dose sufficient to induce DNA damage, as evidenced by the accumulation of 53BP1 repair foci (Fig. 3A), but insufficient to promote extensive cell death (supplementary material Fig. S2C,D). We also verified that expression of PAGFP–H2A did not interfere with phosphorylation of endogenous H2AX histone variants, a key step in the repair of DSB (supplementary material Fig. S2E). Chromatin diffusion in BLM-treated cells was significantly decreased compared with that of the control (Fig. 3B), which might be interpreted as a global immobilization of the chromatin in response to DNA damage, but could also reflect an effect intrinsic to H2A such as a shift in histone exchange rates. Indeed, increased H2A histone exchange after UV-induced DNA damage has been reported (Dinant et al., 2013). We did, however, not detect significant differences in the size and intensities of the spots when comparing vehicle and BLM-treated cells (supplementary material Fig. S3A). In addition, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis revealed a predominance of immobile PAGFP–H2A fractions in both vehicle and BLM-treated cells (94.1±0.8% and 94.5±0.5%, respectively; supplementary material Fig. S3B), further indicating that DNA damage did not alter the exchange rate of PAGFP–H2A in our system. The discrepancy with the findings from Dinant et al. (2013) is likely to originate from different measurement time frames and DNA damaging treatments. When performing FRAP analyses, we noticed a reduction in the area of the bleached spots over time, possibly reflecting chromatin diffusion at the margins of the bleached regions (supplementary material Fig. S3C). Interestingly, shrinking of the bleached area was less pronounced in cells treated with BLM or with 10 Gy of ionizing radiation compared with that of the control. These observations are consistent with reduced chromatin mobility after DNA damage.

Fig. 3.

Cells with DNA damage display reduced chromatin mobility. (A) DNA damage induction by BLM was verified in cells expressing mCherry–53BP1ct. (B) Chromatin diffusion in vehicle- and BLM-treated cells. Quantitative data in A,B show the mean±s.e.m; *P<0.05 (unpaired Student's t-test, n = 20). Representative MSD traces are shown. (C) Schematic of the approach used to measure chromatin diffusion in the context of a single DSB. The DSBs were induced and visualized by coexpressing TetR–mCherry and GR–ISceI in U2OS cells with an integrated Tet array flanking an ISceI recognition site (arrowhead). Confocal images of GFP and mCherry fluorescence are shown (upper panels). Nuclear translocation of GR–ISceI upon triamcinolone acetonide (TA) treatment was confirmed by imaging an RFP tag fused to GR–ISceI, in the absence of triamcinolone acetonide (−TA) or 30 min after triamcinolone acetonide treatment (+TA) (lower panels). Note that the weak RFP signals did not interfere with foci localization. (D) Immunostaining for γH2AX (upper panel) and imaging of PCNA–GFP (lower panel) confirms DSB induction after triamcinolone-acetonide-mediated nuclear translocation of GR–ISceI. Tet arrays are indicated with arrowheads. (E) Chromatin diffusion in cells where triamcinolone acetonide was omitted (uncut) and after DNA cleavage by ISceI (cut). The schematics indicate the position of the PAGFP–H2A spots, either overlapping the cleavage site or not overlapping. (F) Chromatin diffusion after exposure to ionizing radiation (IR). Timecourse measurements during recovery were grouped in 10-minute bins. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. (five experiments); *P<0.05 (unpaired Student's t-test). The induction of DSB after ionizing radiation was confirmed in cells expressing GFP-tagged 53BP1 (right panels). Scale bars: 10 µm.

Recruitment of DNA damage sensors to a single locus suffices to activate the DDR, even in the absence of DSB (Soutoglou and Misteli, 2008). Therefore, we asked whether one DSB reduces chromatin motions, using a system in which DSB can be induced locally (Soutoglou et al., 2007; Vidi et al., 2012) (Fig. 3C). These cells contain the ISceI meganuclease recognition site flanked by an array of tetracycline response elements, which becomes labeled upon expression of the tetracycline repressor fused to mCherry (TetR–mCherry). Cells coexpressing TetR–mCherry and ISceI fused to the ligand-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR–ISceI) were treated with the artificial glucocorticoid receptor ligand triamcinolone acetonide, which causes nuclear translocation of the enzyme and DNA cleavage, as confirmed with γH2AX and PCNA labeling (Fig. 3D). Decreased chromatin mobility was measured in cells treated with triamcinolone acetonide versus controls (Fig. 3E). The effect, however, was not as pronounced as the one measured after BLM exposure, suggesting that higher DSB densities upon genotoxic drug treatment more effectively alter chromatin mobility. It should also be noted that only 60% of cells treated with triamcinolone acetonide had DSBs labeled with γH2AX at the Tet arrays. Hence, the effect of single DSB on chromatin mobility is likely underestimated in our experiments. This tendency towards reduced chromatin mobility was measured when one of the two PAGFP–H2A foci overlapped with the ISceI cleavage site, but not in the absence of overlap (Fig. 3E), suggesting that a single DSB reduces chromatin mobility at or near the break site, but not throughout the nucleoplasm. To gain a better time resolution of chromatin mobility after DNA damage, PAGFP-PPT measurements were performed as timecourses following treatment with ionizing radiation. Interestingly, changes in chromatin mobility after ionizing radiation were time dependent (Fig. 3F). After an initial decrease, chromatin mobility increased above control levels and eventually returned to normal.

It is generally assumed that DNA breaks do not diffuse freely in the nucleoplasm. Using soft X-rays generating tracks of DSB, Nelms and colleagues (Nelms et al., 1998) showed positional stability of DNA lesions. Similar conclusions were drawn from time-lapse measurements of 53BP1 repair foci (Kruhlak et al., 2006; Jakob et al., 2009) and from recordings of the position of broken DNA ends (Soutoglou et al., 2007). The decrease in chromatin movements measured herein after BLM treatment is in agreement with these observations. In one report, however, 53BP1 repair foci were shown to diffuse more rapidly compared with undamaged chromatin labeled with Cy3–dUTP (Krawczyk et al., 2012). The latter study measured the diffusion of chromatin at DSBs, whereas our PAGFP-PPT approach measured chromatin diffusion in the context of DNA damage, but not exclusively at broken DNA ends. Indeed, photoactivated PAGFP–H2A spots were larger than repair foci and contained an estimated ∼106 base pairs. A global freeze of chromatin movements is not incompatible with increased mobility of the chromatin flanking DSB. Other possible explanations for discrepancies regarding chromatin mobility include the use of different cell lines, distinct treatments to induce DNA damage and – importantly – different time scales used for the analyses. Our measurements after treatment with ionizing radiation indeed reveal a time-dependent response.

It is interesting to contrast mammalian cells and yeasts, which both repair DSB predominantly with two competing pathways – homologous recombination, which uses a DNA template to restore the genetic information, and error-prone non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), which simply religates broken ends. Homologous recombination is the major repair mechanism in yeast, whereas mammalian cells mostly use NHEJ. Recent studies in yeast have revealed increased chromosome movement after DNA cleavage (Dion et al., 2012; Miné-Hattab and Rothstein, 2012), which might facilitate homology search during homologous recombination (Dion and Gasser, 2013). Conversely, it is expected that for NHEJ, chromatin movements might increase the frequency of genomic translocation and reduce the rate of reannealing – except under specific circumstances that necessitate long-range DNA end-joining, for example during V(D)J recombination (Difilippantonio et al., 2008). Therefore, we propose that chromatin diffusion is tightly controlled to accommodate repair pathway commitments and the different stages of the DDR. The initial freeze of the chromatin might represent a mechanism to reduce encounters with other DNA breaks that can result in deleterious genomic rearrangements. Subsequent chromatin relaxation after stabilization of the broken DNA strands might then facilitate the repair process.

Decreased chromatin diffusion in response to DSBs measured in this study suggests the existence of stabilizing factors controlled by the DDR. Identifying these factors will be important for our basic understanding of the structure and function of the genome, and the PAGFP-PPT method could be implemented as a screening platform for this purpose. Such knowledge will notably be relevant to cancer control, because genomic translocations – which obviously require chromatin mobility – often promote the development of secondary tumors after initial chemotherapy with DNA-damaging agents. Beyond the DNA repair field, PAGFP-PPT could be applied to characterize chromatin behavior with respect to nuclear domains and bodies, to address the impact of (aneu)ploidy on chromatin dynamics and to define chromatin mobility in eu- and heterochromatin domains. Further development of PAGFP–histone tracking, for example with high-density arrays of photoactivated spots, will enable topological and temporal mapping of chromatin dynamics in live cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell transfection and immunostaining

U2OS cells were cultured with DMEM/H14 supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C under 5% CO2 in 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MaTek) and were transfected the next day with plasmids encoding PAGFP–H2A (Pang et al., 2013), PAGFP–H4 (Hihara et al., 2012), the C-terminal fragment of 53BP1 fused to mCherry (mCherry–53BP1ct; Addgene #19835), GFP– or RFP–PCNA (Leonhardt et al., 2000), or GFP alone using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). In validation experiments, ATP depletion was performed according to Smeenk et al. (2013) and was confirmed using a bioluminometric assay (Biotium). Alternatively, cells were fixed with formaldehyde (4%; 20 min; Sigma). Immunostaining was performed as described previously (Abad et al., 2007), using antibodies against γH2AX (Millipore) and cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175; Cell Signaling). Fluorescent signals were imaged with an Olympus IX70 using a 100× oil objective.

DNA damage

Cells were treated with 20 mU/ml of bleomycin (Calbiochem) for 1 hour or were exposed to 10 Gy ionizing radiation in a Gammacell 220 irradiator (Nordion). To induce individual DSBs, GR–ISceI was expressed in U2OS cells with tetracycline response elements flanking the ISceI site. Nuclear translocation of GR–ISceI was induced with triamcinolone acetonide (0.1 µM; 30 min). TetR–mCherry coexpressed with GR–ISceI labeled the loci.

GFP photoactivation and tracking

A Zeiss CLSM710 confocal microscope with environmental control (37°C, 5% CO2; Pecon) and a 63× water-immersion objective (NA 1.2) was used for GFP photoactivation and imaging. Two spots with a radius of <0.5 µm were photoactivated with the 405-nm laser line (200 µs dwell time; 30 mW power). Images were collected after photoactivation at 3.3 frames per second using the 488-nm line. Spot positions were determined by fitting to a 2D PSF (Yildiz et al., 2003). Assuming that each spot went to N steps of random walk separated by a lag time Δt, the spot positions r at t+Δt are described as:

| (1) |

Δr(Δt) is the displacement between steps and ΔrCell is the movement of the nucleus. After subtracting equation (1) for spots r1 and r2 we obtain:

| (2) |

The left term in equation (2) is the distance between two spots. We define DIS(t) = r1(t) − r2(t), and simplify equation (2) as:

| (3) |

The MSD of the distance between spots was calculated and plotted with a time lag of 0–N/4 to ensure accuracy (Saxton, 1997). Diffusion coefficients D were calculated by fitting MSD curves with a confined/constrained Brownian model (Neumann et al., 2012).

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

FRAP was performed on a Zeiss CLSM710. GFP was photoactivated by scanning a square region (14×14 µm) with the 405-nm laser line. Within this region, a 16-µm2 square was bleached using the 488-nm laser (20 iterations, 35 mW). Analysis was performed using the ZEN software (Zeiss).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacques Neefjes (Netherland Cancer Institute), Titia de Lange (Rockefeller University), Edith Heard (Institut Curie) and Cristina Cardoso (Technische Universität Darmstadt) for kindly providing DNA constructs and Tom Misteli (National Institutes of Health) for kindly providing the U2OS-ISceI cell system. We also thank Chris Duffey for assistance in the blind analysis of FRAP experiments.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

J.L. and P.-A.V. conceived and designed the experiments. P.-A.V. performed cellular work and imaging. J.L. developed the SPT and PPT algorithms and analyzed the particle tracking data. S.A.L. gave conceptual advice. J.M.K.I. supervised the project. P.-A.V., J.L., S.A.L. and J.M.K.I. wrote or edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number K99CA163957 to P.-A.V.]; and the Keck Foundation (to J.I. and S.A.L.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.161885/-/DC1

References

- Abad P. C., Lewis J., Mian I. S., Knowles D. W., Sturgis J., Badve S., Xie J., Lelièvre S. A. (2007). NuMA influences higher order chromatin organization in human mammary epithelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 348–361 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouly G., Abad P. C., Knowles D. W., Lelièvre S. A. (2007). The control of tissue architecture over nuclear organization is crucial for epithelial cell fate. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1596–1606 10.1242/jcs.03439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb J. R., Boyle S., Perry P., Bickmore W. A. (2002). Chromatin motion is constrained by association with nuclear compartments in human cells. Curr. Biol. 12, 439–445 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00695-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difilippantonio S., Gapud E., Wong N., Huang C. Y., Mahowald G., Chen H. T., Kruhlak M. J., Callen E., Livak F., Nussenzweig M. C. et al. (2008). 53BP1 facilitates long-range DNA end-joining during V(D)J recombination. Nature 456, 529–533 10.1038/nature07476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinant C., Ampatziadis-Michailidis G., Lans H., Tresini M., Lagarou A., Grosbart M., Theil A. F., van Cappellen W. A., Kimura H., Bartek J. et al. (2013). Enhanced chromatin dynamics by FACT promotes transcriptional restart after UV-induced DNA damage. Mol. Cell 51, 469–479 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion V., Gasser S. M. (2013). Chromatin movement in the maintenance of genome stability. Cell 152, 1355–1364 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion V., Kalck V., Horigome C., Towbin B. D., Gasser S. M. (2012). Increased mobility of double-strand breaks requires Mec1, Rad9 and the homologous recombination machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 502–509 10.1038/ncb2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdel F., Schubert T., Marth C., Längst G., Rippe K. (2010). Human ISWI chromatin-remodeling complexes sample nucleosomes via transient binding reactions and become immobilized at active sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19873–19878 10.1073/pnas.1003438107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A. D., Allis C. D., Bernstein E. (2007). Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell 128, 635–638 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun P., Laroche T., Shimada K., Furrer P., Gasser S. M. (2001). Chromosome dynamics in the yeast interphase nucleus. Science 294, 2181–2186 10.1126/science.1065366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihara S., Pack C. G., Kaizu K., Tani T., Hanafusa T., Nozaki T., Takemoto S., Yoshimi T., Yokota H., Imamoto N. et al. (2012). Local nucleosome dynamics facilitate chromatin accessibility in living mammalian cells. Cell Reports 2, 1645–1656 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob B., Splinter J., Durante M., Taucher-Scholz G. (2009). Live cell microscopy analysis of radiation-induced DNA double-strand break motion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3172–3177 10.1073/pnas.0810987106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk P. M., Borovski T., Stap J., Cijsouw T., ten Cate R., Medema J. P., Kanaar R., Franken N. A., Aten J. A. (2012). Chromatin mobility is increased at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2127–2133 10.1242/jcs.089847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruhlak M. J., Celeste A., Dellaire G., Fernandez-Capetillo O., Müller W. G., McNally J. G., Bazett-Jones D. P., Nussenzweig A. (2006). Changes in chromatin structure and mobility in living cells at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 172, 823–834 10.1083/jcb.200510015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Maitra A., Sumit M., Ramaswamy S., Shivashankar G. V. (2014). Actomyosin contractility rotates the cell nucleus. Sci. Rep. 4, 3781 10.1038/srep03781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt H., Rahn H. P., Weinzierl P., Sporbert A., Cremer T., Zink D., Cardoso M. C. (2000). Dynamics of DNA replication factories in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 149, 271–280 10.1083/jcb.149.2.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. F., Straight A., Marko J. F., Swedlow J., Dernburg A., Belmont A., Murray A. W., Agard D. A., Sedat J. W. (1997). Interphase chromosomes undergo constrained diffusional motion in living cells. Curr. Biol. 7, 930–939 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00412-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miné-Hattab J., Rothstein R. (2012). Increased chromosome mobility facilitates homology search during recombination. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 510–517 10.1038/ncb2472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miné-Hattab J., Rothstein R. (2013). DNA in motion during double-strand break repair. Trends Cell Biol. 23, 529–536 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T., Soutoglou E. (2009). The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 243–254 10.1038/nrm2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanari Y., Ziegler-Birling C., Torres-Padilla M. E. (2013). Live visualization of chromatin dynamics with fluorescent TALEs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 1321–1324 10.1038/nsmb.2680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortusewicz O., Rothbauer U., Cardoso M. C., Leonhardt H. (2006). Differential recruitment of DNA Ligase I and III to DNA repair sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 3523–3532 10.1093/nar/gkl492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar G. J., Sundaramoorthy R., Owen-Hughes T. (2013). Mechanisms and functions of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling enzymes. Cell 154, 490–503 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms B. E., Maser R. S., MacKay J. F., Lagally M. G., Petrini J. H. (1998). In situ visualization of DNA double-strand break repair in human fibroblasts. Science 280, 590–592 10.1126/science.280.5363.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann F. R., Dion V., Gehlen L. R., Tsai-Pflugfelder M., Schmid R., Taddei A., Gasser S. M. (2012). Targeted INO80 enhances subnuclear chromatin movement and ectopic homologous recombination. Genes Dev. 26, 369–383 10.1101/gad.176156.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang B., Qiao X., Janssen L., Velds A., Groothuis T., Kerkhoven R., Nieuwland M., Ovaa H., Rottenberg S., van Tellingen O. et al. (2013). Drug-induced histone eviction from open chromatin contributes to the chemotherapeutic effects of doxorubicin. Nat. Commun. 4, 1908 10.1038/ncomms2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton M. J. (1997). Single-particle tracking: the distribution of diffusion coefficients. Biophys. J. 72, 1744–1753 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78820-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber A., Hauer M., Gasser S. M. (2013). Nucleosome remodelers in double-strand break repair. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 23, 174–184 10.1016/j.gde.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk G., Wiegant W. W., Marteijn J. A., Luijsterburg M. S., Sroczynski N., Costelloe T., Romeijn R. J., Pastink A., Mailand N., Vermeulen W. et al. (2013). Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation links the chromatin remodeler SMARCA5/SNF2H to RNF168-dependent DNA damage signaling. J. Cell Sci. 126, 889–903 10.1242/jcs.109413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G., Polo S. E., Almouzni G. (2012). Prime, repair, restore: the active role of chromatin in the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell 46, 722–734 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou E., Misteli T. (2008). Activation of the cellular DNA damage response in the absence of DNA lesions. Science 320, 1507–1510 10.1126/science.1159051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou E., Dorn J. F., Sengupta K., Jasin M., Nussenzweig A., Ried T., Danuser G., Misteli T. (2007). Positional stability of single double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 675–682 10.1038/ncb1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez J., Belmont A. S., Sedat J. W. (2001). Multiple regimes of constrained chromosome motion are regulated in the interphase Drosophila nucleus. Curr. Biol. 11, 1227–1239 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00390-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidi P. A., Chandramouly G., Gray M., Wang L., Liu E., Kim J. J., Roukos V., Bissell M. J., Moghe P. V., Lelièvre S. A. (2012). Interconnected contribution of tissue morphogenesis and the nuclear protein NuMA to the DNA damage response. J. Cell Sci. 125, 350–361 10.1242/jcs.089177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. G., Allis C. D., Chi P. (2007). Chromatin remodeling and cancer. Part II: ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Trends Mol. Med. 13, 373–380 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S. C., Spakowitz A. J., Theriot J. A. (2012). Nonthermal ATP-dependent fluctuations contribute to the in vivo motion of chromosomal loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7338–7343 10.1073/pnas.1119505109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesmeijer K., Krouwels I. M., Tanke H. J., Dirks R. W. (2008). Chromatin movement visualized with photoactivable GFP-labeled histone H4. Differentiation 76, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz A., Forkey J. N., McKinney S. A., Ha T., Goldman Y. E., Selvin P. R. (2003). Myosin V walks hand-over-hand: single fluorophore imaging with 1.5-nm localization. Science 300, 2061–2065 10.1126/science.1084398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.