Abstract

Objective: to examine the prevalence of frailty and disability in people aged 60 and over and the proportion of those with disabilities who receive help or use assistive devices.

Methods: participants were 5,450 people aged 60 and over from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Frailty was defined according to the Fried criteria. Participants were asked about difficulties with mobility or other everyday activities. Those with difficulties were asked whether they received help or used assistive devices.

Results: the overall weighted prevalence of frailty was 14%. Prevalence rose with increasing age, from 6.5% in those aged 60–69 years to 65% in those aged 90 or over. Frailty occurred more frequently in women than in men (16 versus 12%). Mobility difficulties were very common: 93% of frail individuals had such difficulties versus 58% of the non-frail individuals. Among frail individuals, difficulties in performing activities or instrumental activities of daily living were reported by 57 or 64%, respectively, versus 13 or 15%, respectively, among the non-frail individuals. Among those with difficulties with mobility or other daily activities, 71% of frail individuals and 31% of non-frail individuals said that they received help. Of those with difficulties, 63% of frail individuals and 20% of non-frail individuals used a walking stick, but the use of other assistive devices was uncommon.

Conclusions: frailty becomes increasingly common in older age groups and is associated with a sizeable burden as regards difficulties with mobility and other everyday activities.

Keywords: frailty, disability, assistive devices, older people

Introduction

Frailty is a clinical condition characterised by vulnerability to poor resolution of homeostasis after a stressor event, resulting from loss of physiological reserve across multiple systems [1–3]. It has adverse consequences not just in terms of morbidity and mortality, but also as regards disability and possible need for help with daily activities. Information on the prevalence of frailty and on the extent of disability in community-dwelling older populations, particularly among the frail, is therefore potentially important for planning health and social care provision.

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) is a population-based sample of older men and women [4, 5]. We used data on people aged 60 to over 90 years to examine the prevalence of frailty, the extent of disability in frail and non-frail individuals, and whether those who reported difficulties were receiving help. As assistive devices can improve independence in those with functional limitations [6], we also examined the prevalence of their use.

Methods

Participants

The sample for ELSA was based on people aged ≥50 years who had participated in the Health Survey for England [4]. At Wave 1 in 2002–03, 11,392 people participated. At Wave 4 in 2008–09, core cohort members were invited to have a visit from a nurse for measurements of physical function and anthropometry. Ethical approval was obtained from the Multicentre Research and Ethics Committee. Participants gave written informed consent.

Measures

Frailty

Maximum handgrip strength was measured three times on each side using a dynamometer; the best of these measurements was used for analysis. Height and weight were measured with a portable stadiometer and electronic scales, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kg)/height (in m2). Gait speed was assessed in participants aged 60 and over by measuring the time taken to walk a distance of 8 feet at usual pace; the walk was repeated and the mean of the two measurements was calculated. Participants responded to questions about the frequency with which they did vigorous, moderate or mild exercise. We ranked the combinations of responses to these questions according to the amount and intensity of exercise involved to provide an estimate of usual physical activity. Symptoms of depression were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [7]. We used these data, together with information on weight at the initial survey, to derive an indicator of physical frailty at Wave 4 in people aged ≥60 years using the Fried criteria [1]. Physical frailty is defined as the presence of three or more of the following conditions: unintentional weight loss, weakness, self-reported exhaustion, slow walking speed and low physical activity. We operationalised these criteria using definitions similar to those used in Fried's original studies [1, 8]: weight loss was defined as either loss of ≥10% of body weight since Wave 2 or current BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; weakness was defined as maximum grip strength in the lowest 20% of the distribution, taking account of sex and BMI; exhaustion was considered present if the participant responded positively to either of the CES-D questions: ‘Felt that everything I did was an effort in the last week’ or ‘Could not get going in the last week’; slow walking speed was defined as a walking speed in the lowest 20% of the distribution, taking account of sex and height; and low physical activity was defined as activity in the lowest sex-specific 20% of the distribution.

Disability

Participants were asked whether they had difficulty doing any of 10 activities that involved mobility—such as walking 100 yards, climbing a flight of stairs—or any of 15 other everyday activities—such as dressing, bathing. They were asked to exclude difficulties they expected to last <3 months. Participants who had difficulty with any of these activities were asked whether anyone ever helped with these activities and whether they used any of seven types of devices—such as walking stick, or personal alarm to call for assistance.

Statistical analysis

All prevalence estimates were weighted for sampling probabilities, non-response and differential sample loss since earlier waves of data collection to make them reflect the population from whom the sample was drawn.

Results

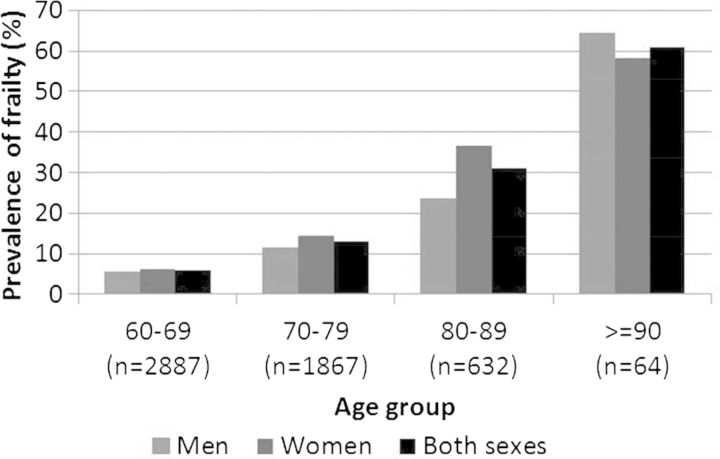

The overall weighted prevalence of frailty was 14% (12% in men, 16% in women). Prevalence rose exponentially with increasing age, increasing from 6.5% in those aged 60–69 years to 65% in those aged 90 or over (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Weighted prevalence of frailty in 2008–09 according to age and sex.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of limitations in mobility and other daily activities according to frailty status. Mobility difficulties were very common, particularly among frail individuals, 93% of whom reported having one or more of such difficulties compared with 58% of the non-frail individuals. The high prevalence of mobility difficulties among frail individuals reflects the fact that 90% of them were classified as having slow walking speed, one of the criteria for frailty. Among frail people, difficulties in performing activities of daily living (ADL) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were reported by 57 or 65%, respectively, compared with 14 or 16%, respectively, among non-frail people. All forms of mobility limitation were associated with increased likelihood of difficulties with ADL or IADL in frail people, with odds ratios ranging from 2.6 (reaching up) to 5.9 (getting out of a chair) and 2.1 (sitting) to 6.4 (lifting), respectively. The most common difficulties reported by frail people were doing work round the house and garden, dressing, shopping for groceries, and bathing or showering.

Table 1.

Weighted prevalencea of limitations in mobility and other daily activities, receipt of help and use of aids according to frailty status in people aged 60 years or over (n = 5,450)

| Frail (n = 644b) | Not frail (n = 4,806b) | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of one or more limitations, % | ||

| Mobility | 93.2 | 58.1 |

| ADLs | 57.1 | 13.7 |

| IADLs | 64.5 | 15.9 |

| Prevalence of specific limitations in mobility, % | ||

| Walking 100 yards | 48.4 | 5.68 |

| Sitting for about 2 h | 24.9 | 9.01 |

| Getting out of a chair after sitting for long periods | 55.3 | 21.8 |

| Climbing several flights of stairs without resting | 79.1 | 32.6 |

| Climbing one flight of stairs without resting | 53.4 | 8.45 |

| Stooping, kneeling or crouching | 69.2 | 33.3 |

| Pulling or pushing large objects like a living-room chair | 53.6 | 11.7 |

| Lifting or carrying weights over 10 pounds like a heavy bag of groceries | 68.7 | 17.4 |

| Reaching or extending arms above shoulder level | 28.8 | 7.53 |

| Picking up a 5 p coin from a table | 16.6 | 3.49 |

| Prevalence of specific limitations in ADL or IADL, % | ||

| Dressing | 40.0 | 9.34 |

| Walking across a room | 8.21 | 0.54 |

| Bathing or showering | 34.1 | 5.45 |

| Eating, such as cutting up food | 5.33 | 0.64 |

| Getting in or out of bed | 15.9 | 2.29 |

| Using a toilet, including getting up or down | 8.71 | 1.42 |

| Using a map | 14.5 | 3.26 |

| Recognising when you are in physical danger | 4.60 | 0.37 |

| Preparing a hot meal | 16.7 | 0.86 |

| Shopping for groceries | 36.3 | 3.66 |

| Making telephone calls | 6.12 | 1.58 |

| Communication (speech, hearing or eyesight) | 7.59 | 3.60 |

| Taking medications | 5.59 | 0.72 |

| Doing work round the house or garden | 52.3 | 8.73 |

| Managing money | 8.00 | 1.11 |

| In subset with limitations in mobility or ADL or IADL | (n = 603b) | (n = 2,768b) |

| Ever receives help from other people, % | 71.0 | 31.4 |

| Uses walking stick or cane, % | 63.0 | 20.2 |

| Uses zimmer frame or walker, % | 14.3 | 1.25 |

| Uses buggy or scooter, % | 8.99 | 1.27 |

| Uses manual wheelchair, % | 10.9 | 0.96 |

| Uses electric wheelchair, % | 1.94 | 0.06 |

| Uses elbow crutches, % | 2.28 | 1.03 |

| Uses personal alarm for help after falls, % | 13.7 | 1.43 |

aPrevalence weighted for sampling probabilities, non-response and differential sample loss since earlier waves.

bUnweighted bases.

Among those who had reported having difficulties with mobility or other daily activities, 71% of frail individuals and 31% of non-frail individuals reported that they received help from other people. The proportion of frail people who received such help varied depending on the activity with which they had difficulty: while 98% of frail individuals reported that they received help with shopping or doing work round the house or garden, only 67% of frail people received help with the more intimate activities of dressing or bathing.

By far, the most commonly used aid among those who reported difficulties with mobility or other daily activities was a walking stick, used by 63% of those who were frail and 20% of those who were not frail. The proportion using powered mobility aids was very small.

Discussion

Little is known about the prevalence of frailty in the United Kingdom. In two previous studies both using the Fried phenotype model of frailty [1], one, based on people aged 64–74 in Hertfordshire, found a prevalence of 8.5% in women and 4.1% in men [9], and another, based on an earlier wave of data from the ELSA, found a prevalence of 9% in women and 7% men in those aged 65 and over, but there was no examination of how these rates varied with age [10]. Here, using a wider age range and the most recent available data on frailty in this cohort, we confirmed these earlier observations of sex difference in prevalence and showed how markedly prevalence rises with age. Our findings are consistent with the few previous studies in other countries that have examined age variations in frailty prevalence [11, 12]. Prevalence estimates are inevitably definition dependent. As Collard et al. [11] have shown, differences in the operationalisation of frailty status have resulted in wide variations in prevalence between studies.

Results of our study suggest that there may be a considerable number of older people in the UK who have functional difficulties with some daily activities yet are not receiving help. This appears to be particularly the case with more intimate activities such as bathing or dressing. No information was available on whether such individuals wished to be provided with assistance. Given current trends for moving health care out of hospital into the home and expenditure cuts to social care budgets, such data are needed for accurately planning provision of support and care.

Few previous studies in the UK have examined the use of assistive devices in older people. In a survey of people aged 72–82, a walking stick was the most frequent device used (by 29%) [13]. Here too, we found that walking sticks were by far the commonest aid used by those with difficulties in mobility or other ADLs, particularly among frail individuals. The low prevalence of the use of powered mobility aids may in part reflect their cost: buggys/scooters are not provided by the NHS and the criteria for receiving a NHS-supplied electric wheelchair are very strict [14, 15].

In this survey of older people, the prevalence of frailty was higher in women than in men and increased exponentially with increasing age. Almost all frail individuals had problems with mobility. This high prevalence is unsurprising, given that slow walking speed, one of the criteria for phenotypic frailty, was present in nearly all those classified as frail. Over half of the frail individuals had problems with other ADLs.

Key points.

• The prevalence of frailty rises exponentially with age.

• Almost all frail individuals had problems with mobility, and over half had problems with other ADLs.

• A significant proportion of frail individuals with disabilities receive no help from other people.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

The funding for ELSA is provided by the National Institute of Aging in the United States and a consortium of UK government departments coordinated by the Office for National Statistics. The developers and funders of ELSA and the Archive do not bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council. MRC_MC_UU_12011/2 MRC-MC-UP_A620_1015.

Acknowledgements

The data were made available through the UK Data Archive. ELSA was developed by a team of researchers based at the National Centre for Social Research, University College London and the Institute for Fiscal Studies. The data were collected by the National Centre for Social Research.

References

- 1.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman H, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J, et al. Frailty: an emerging research and clinical paradigm–issues and controversies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:731–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1640–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot M, Oldfield Z, Clemens S, et al. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing: Waves 0–5, 1998–2011 [Computer File] 20th edition. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor]; 2013. SN: 5050. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verbrugge LM, Rennert C, Madans JH. The great efficacy of personal and equipment assistance in reducing disability. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:384–92. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffick DE. The HRS Working Group. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report DR-005 [online report]. 2000 [updated 2000] http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-005.pdf. (10 March 2013, date last accessed)

- 8.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women's health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:262–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syddall H, Roberts HC, Evandrou M, Cooper C, Bergman H, Aihie SA. Prevalence and correlates of frailty among community-dwelling older men and women: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing. 2010;39:197–203. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubbard RE, Lang IA, Llewellyn DJ, Rockwood K. Frailty, body mass index, and abdominal obesity in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:377–81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1487–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harttgen K, Kowal P, Strulik H, Chatterji S, Vollmer S. Patterns of frailty in older adults: comparing results from higher and lower income countries using the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and the Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE) PLoS One. 2013;8:e75847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pain H, Gale CR, Watson C, Cox V, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Readiness of elders to use assistive devices to maintain their independence in the home. Age Ageing. 2007;36:465–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank AO, Ward JH, Orwell NJ, McCullagh C, Belcher M. Introduction of the new NHS electric powered indoor/outdoor chair (EPIOC) service: benefits, risks and implications for prescribers. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14:665–73. doi: 10.1191/0269215500cr376oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank AO, De Souza LH. Recipients of electric-powered indoor/outdoor wheelchairs provided by a national health service: a cross-sectional study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:2403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]