Abstract

Objectives

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin. Preclinical studies have identified up-regulation of the critical antiapoptosis gene bcl-2 in MCC. We conducted a multicenter phase II trial of the novel bcl-2 antisense agent (G3139, Genasense) in patients with advanced MCC.

Methods

Twelve patients (9 men, 3 women) with histologically confirmed metastatic or regionally recurrent MCC were enrolled. Ten patients (83%) had received prior chemotherapy. Eight patients (67%) had Karnofsky performance status of 90 to 100. Patients received continuous IV infusion of G3139 (7 mg/kg/d) via central venous access in an outpatient setting for 14 days, followed by a 7-day rest period. Response was assessed at 6-week intervals. Patients were allowed to continue therapy until unacceptable toxicity or disease progression.

Results

No objective responses were observed. The best response was stable disease in 3 patients and progressive disease in 9 patients. A median of 4 doses per patient (total 46 doses) was administered. Dose delays and/or reductions were required in 6 patients. One patient developed grade 4 lymphopenia. One patient developed grade 3 renal failure characterized by grade 3-elevated creatinine and grade 4 hyperkalemia. Other grade 3 events included cytopenia (n = 5), aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotranferease elevation (n = 3), hypophosphatemia (n = 2), and pain (n = 1). The most frequent grade 1 to 2 toxicities were elevated creatinine, ALT elevation, hypokalemia, lymphopenia, and fatigue.

Conclusions

Bcl-2 antisense therapy (G3139) was well tolerated among patients with advanced MCC. Although probable antitumor activity was documented in 1 patient, no objective responses per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria were observed.

Keywords: Bcl-2 antisense therapy, G3139, Merkel cell carcinoma, phase II trial

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), or neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, is an uncommon and often aggressive malignancy that was originally described by Toker in 1972 as trabecular carcinoma of the skin.1 Because of the relative rarity of this tumor, its natural history is not well defined, and most knowledge has been gained from small case series.2 MCC is most frequently identified in sun-exposed areas and is uncommon among patients less than 50 years old. A slight male predominance is noted (2.3:1).3 The prevalence of MCC seems to be higher among immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients and patients with HIV infection.3 Interestingly, 3% of cases present with metastasis from an unknown primary, suggesting that the immune system may play a role in regression of the primary tumor in some patients.4 The majority of patients (70%) present with localized disease. Unfortunately, even after excision, the incidence of local recurrence remains high (up to 30%).5 Reported incidences of regional and distant metastatic disease vary widely (9%–26% for regional nodal metastases; 18%-52% for distant metastases).3 It is important to note that most reports in the literature present patient series accrued before the era of sentinel lymph node localization and biopsy. With the current practice of pathologic staging by sentinel lymph node localization and biopsy in all patients, the reported incidence of subsequent regional metastases may change. The role of adjuvant external beam radiation in the treatment of MCC remains controversial. However, at a minimum it seems that radiation should be offered to patients with poor prognostic indicators, if not to all patients with resected MCC.2,4,6–10 Historically, MCC treatment has been modeled after treatment of small cell carcinoma of the lung, the most common high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma.11–17 Unfortunately, despite aggressive combination chemotherapy regimens such as cisplatin and etoposide, clinical outcome has been poor, characterized by brief response durations of weeks to months. In the initial report of the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group TROG 96:07, a high rate of locoregional control and a 3-year overall survival of 76% were obtained among 55 patients with high-risk MCC treated with concurrent carboplatin and etoposide with radiotherapy.9 At subsequent analysis, the addition of chemotherapy did not seem to have any effect on survival by multivariate analysis.12

Bcl-2 is an oncoprotein originally identified as the t(14; 18) chromosomal translocation found in follicular lymphomas.18 It is believed to have a critical role in inhibiting cell death via the intrinsic (mitochondria-dependent) pathway of apoptosis.19 Antisense bcl-2, G3139 (Genasense; oblimersen sodium, Genta, Berkeley Heights, NJ) is an 18-mer phosphorothioate oligonucleotide that binds to the first 6 codons of the open reading frame of human bcl-2 mRNA, resulting in down-regulation of bcl-2 with stimulation of apoptosis.20 In addition to its effects on apoptosis, antisense bcl-2 is believed to facilitate nonapoptotic cell death by autophagy, to inhibit tumor angiogenesis via inhibition of NFκB activity with resultant decreased production of vascular endothelial growth factor, and to exert immunostimulatory effects via activation of the innate immune response and stimulation of cellular responses such as the IFN cascade.21

Preclinical studies demonstrating dose-dependent growth inhibition of several human tumor cell lines and implanted xenograft models in response to treatment with G3139 provided the rationale for assessing the effect of G3139 in patients with MCC.19 Specifically, Schlagbauer-Wadl et al22 showed that antisense down-regulation of bcl-2 mRNA increased apoptosis and inhibited growth in MC-MA 11 MCC xenografts. Additionally, laboratory models demonstrated that resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy is mediated by bcl-2 protein, making antisense bcl-2 a potentially important agent for combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy.19

The choice of the dose and schedule of G3139 was based upon initial experience with G3139 in patients with advanced solid tumors. A phase I dose-escalation trial of G3139 alone or with paclitaxel was carried out in 35 patients with advanced solid tumors.23 Transient elevation of serum transaminases that responded to dose reduction occurred at the 7 mg/kg/d dose. Two of the 3 patients treated at this level experienced major clinical response. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic data from this study suggested a linear relationship between dose and plasma levels up to 7 mg/kg/d, and a 2-hour half-life of elimination at the end of the infusion.23 Similarly, a phase I and II trial of G3139 with dacarbazine in patients with malignant melanoma showed that the regimen was well tolerated up to 7 mg/kg/d.24 Dose-limiting toxicity was grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia observed in 2 patients treated at 12 mg/kg/d. These results and those from multiple other phase I and II trials suggest that the dose of 7 mg/kg/d on a 14-day dosing schedule provides biologically relevant plasma levels, down-regulates target Bcl-2 protein, and gives an acceptable safety profile. For these reasons, the present dose and schedule were chosen.

Up-regulation of Bcl-2 in MCC cells as compared with normal Merkel cells has been demonstrated,22 providing the molecular rationale for the study of G3139 in this rare disease. The primary objective of this trial was to determine the clinical activity of bcl-2 antisense therapy (G3139, Genasense) in patients with histologically confirmed metastatic or regionally recurrent MCC, as assessed by objective response rates. The secondary objective was to assess the toxicity of G3139 in this group of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

A National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored open-label phase II trial (NCI Protocol #5907) of bcl-2 antisense therapy (G3139, Oblimersen sodium, Genasense) in patients with advanced MCC was conducted at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center and at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center beginning in June 2004 following approval by the Institutional Review Boards at each institution. Eligibility criteria included measurable, histologically or cytologically confirmed metastatic or regionally recurrent MCC; age ≥18 years; Karnofsky performance status ≥60%; and normal organ and marrow function (leukocytes ≥3000/μL, absolute neutrophil count ≥1500/μL, platelet count ≥100,000/μL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotranferease (ALT) ≤2.5 times upper limit of normal, and normal serum creatinine). Any number of previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy regimens excepting prior G3139 was allowed, as long as at least 3 weeks had passed since cessation of the treatment. Because the effect of G3139 on the developing fetus is unknown, women of child-bearing potential and men of any age were required to use hormonal or barrier method contraception before trial entry and during the duration of the trial. Patients with known brain metastases, prior irradiation to ≥25% of the bone marrow, or peripheral neuropathy ≥grade 2 were excluded. Patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation (except 1-mg warfarin for Mediport patency) or having uncontrolled intercurrent illness were excluded. Each patient gave informed consent to participate in the trial.

Study Design

This study was a phase II, open-label, nonrandomized trial employing a Simon two-stage design to evaluate the primary end point of overall response rate [partial response (PR) or complete response (CR)]. The null hypothesis was that the overall response rate to G3139 is no better than 5%. A response rate of 20% or greater would be sufficient to justify further study. If no responses were observed in the first stage of 12 patients, the trial would be terminated. If 1 or more response was seen, an additional 25 patients would be enrolled. To recommend further study, 4 or more of the 37 patients were required to demonstrate response. This design provides ≤10% probability of incorrectly recommending an ineffective drug for further study (type I error), and ≤10% probability of incorrectly rejecting a promising drug (type II error).

Treatment Regimen and Toxicity Assessment

G3139 was administered as a continuous intravenous infusion via indwelling central venous access at a dose of 7 mg/kg/d for 14 days followed by a 7-day rest period. Antiemetic therapy and growth factor support were not used on a prophylactic basis. History, physical examination, and routine laboratory studies including complete blood count, chemical profile, calcium, total protein, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, ALT, AST, phosphate, lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, and prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time/international normalized ratio were obtained at baseline and on day 1 of each treatment cycle. Some of the laboratory studies were required weekly for the first cycle. Evaluation of toxicity per NCI Common Toxicity Criteria Version 3.0 was performed weekly during the first cycle of therapy and on day 1 of subsequent treatment cycles. Patients who developed hypersensitivity reactions to G3139 were treated symptomatically with oral or intravenous antihistamines after evaluation for infection at the discretion of the investigator, and were pretreated with antihistamine before subsequent infusions of G3139. Corticosteroid use was indicated only in those patients unresponsive to antihistamines. Therapy was administered until unacceptable adverse event (AE) or disease progression. Grade 1 or 2 toxicities were managed by supportive therapy, without modification of drug administration. Grade 3 hematologic toxicity was managed by holding drug therapy until resolution to ≤grade 2, and resumption at 100% of the dose. Grade 3 nonhematologic or any grade 4 toxicity was managed by holding drug therapy until resolution to ≤grade 2, and resumption at 75% of the dose. If the toxicity did not resolve to ≤grade 2 within 2 weeks, the patient was removed from the trial.

Assessment of Disease Response

Measurement of the tumor indicator lesion(s) was performed with photography, chest radiography, computed tomography (CT) scan, or other diagnostic tests as indicated, at baseline and after every 2 treatment cycles. Patients exhibiting a clinical response or stable disease (SD) were allowed to continue therapy until disease progression or the development of unacceptable toxicity. Objective response was assessed using the international criteria proposed by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) Committee.25 Antisense Bcl-2 is believed to stimulate cell death via apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis, and exert immunostimulatory effects. However, methods of quantifying objective clinical response because of all of these mechanisms are not currently standardized and validated. We used RECIST criteria to define objective response as reduction in tumor size because of expected induction of apoptosis of the tumor as a mechanism of G3139.

RESULTS

Patients

Between June 2004 and July 2006, a total of 13 patients (10 men, 3 women) were accrued to this trial. One patient developed progressive renal insufficiency before initiating drug therapy, and was therefore ineligible. Thus, a total of 12 patients (9 men, 3 women) were treated on this trial. Clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The median age was 62.5 years (range, 57–77). All 12 patients were of white, non-Hispanic ethnicity. Ten of the patients (83%) had received prior chemotherapy, and 5 (42%) had received previous radiation therapy. Eight patients (67%) had initial Karnofsky performance status of 90% or 100%. Half of the patients had locoregional disease only, and half had distant visceral metastases.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 12 (100) |

| Age (yrs) | |

| Median | 62.5 |

| Range | 57–77 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (75) |

| Female | 3 (25) |

| Site of accrual | |

| Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center | 7 (58) |

| Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center | 5 (42) |

| Baseline Karnofsky performance status | |

| 90 or 100% | 8 (67) |

| 80% | 1 (8) |

| 70% | 3 (25) |

| Site of metastasis | |

| Locoregional only | 6 (50) |

| Locoregional plus distant visceral | 4 (33) |

| Distant visceral only | 2 (17) |

| No. previous chemotherapy regimens | |

| 2 | 8 (66) |

| 1 | 2 (17) |

| 0 | 2 (17) |

| Previous radiation therapy | |

| Yes | 5 (42) |

| No | 7 (58) |

Treatment Administered

Continuous intravenous infusion of G3139 (7 mg/kg/d) was administered via central venous access and disposable infusion pump in the outpatient setting. G3139 was administered for 14 days, followed by a 7-day rest period. The median duration of therapy for all patients was 40 days (range, 17–100). A median of 4 doses per patient (range, 2–6; total 46 doses) was administered. Dose delays and/or reductions were required in 6 patients because of AEs, as detailed below.

Objective Response

No patient achieved a PR or CR. The best response was transient SD in 3 patients (duration of response 56, 53, and 47 days, respectively) and PD in 9 patients. Two of the patients with transient SD ultimately developed PD and 1 withdrew consent for further trial participation. Because there were no clinical responses in the first 12 patients, the trial was terminated after the first stage.

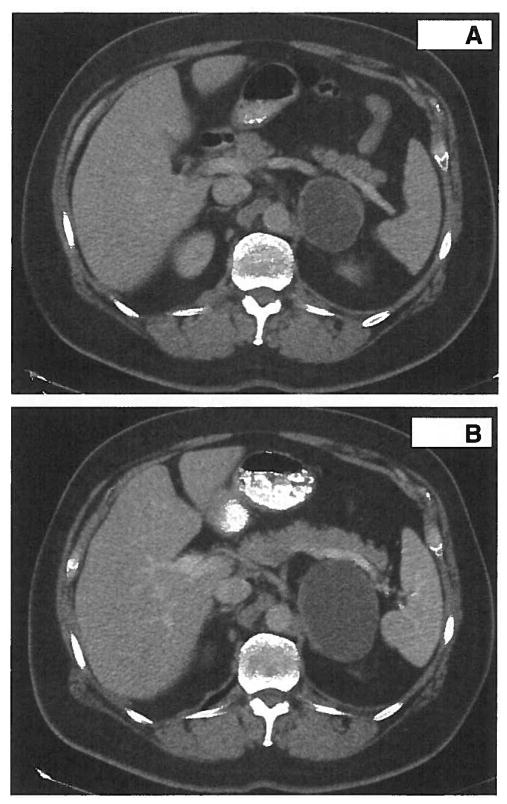

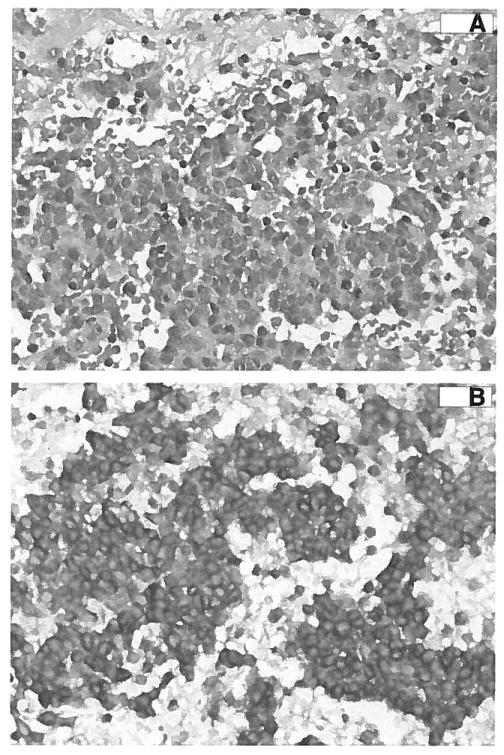

However, a single patient (004) experienced RECIST-defined SD for 53 days with a durable clinical response. Patient 004 is a 56-year-old white man with a MCC with biopsy-proven metastasis to the left side of the scalp and to the adrenal gland. Prestudy CT demonstrated a 1.5-cm left scalp node and a 6.6-cm left adrenal mass with central hypoattenuation suggestive of significant tumor necrosis (Fig. 1A). The patient received 7 mg/kg/d G3139 during the first cycle but the second cycle was delayed by 1 week because of grade 3 AST/ALT elevation, with 25% dose reduction per protocol. After 2 cycles of therapy, the adrenal mass had increased in size from 6.6 to 8.8 cm (Fig. 1B), while the scalp metastasis had disappeared (100% decrease). The tumor density of the adrenal mass increased from 19 to 26 Hounsfield units, suggesting possible hemorrhage or necrosis of the existing cystic mass. Because of the discrepancy in the response between the 2 metastatic sites, the patient was taken off study to undergo resection of the presumed progressive adrenal metastasis. At surgical resection, the adrenal lesion was an 8.9 × 6.6 × 3.1 cm, well circumscribed, hemorrhagic pink-brown mass that was 95% necrotic. Microscopically, it was found to be metastatic MCC with extensive hemorrhage (Fig. 2A). Viable tumor tissue was strongly positive for Bcl-2 protein when tested by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2B). Despite being on observation since surgery and being taken off trial after 2 cycles of G3139, the patient remains without clinical evidence of disease at 22 months after cessation of G3139 treatment.

FIGURE 1.

CT scan demonstrates increase in size of the adrenal metastasis after 2 cycles of therapy in patient 004. Please note the hypoattenuated central area in both scans. A, CT shows a 6.6-cm left adrenal mass. B, After 2 cycles of G3139 therapy, the adrenal mass measured 8.8 cm.

FIGURE 2.

Immunohistochemistry performed on the resected adrenal metastasis of patient 004 demonstrates strong staining for Bcl-2. A, Photomicrograph of the resected adrenal metastasis demonstrates hemorrhage and necrosis. B, Staining for Bcl-2 was strongly positive.

Adverse Events

AEs are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. In general, G3139 was well tolerated. No patient stopped treatment with G3139 because of toxicity. Of 12 patients who received a total of 46 doses on this trial, 6 patients received a total of 14 doses at the reduced dose guidelines. Four patients developed grade 3 AEs (infection n = 1, hypophosphatemia n = 1, ALT/AST elevation n = 1, and elevated creatinine n = 1). In 2 patients, infusion was stopped because of fever managed by hospital admission. The most frequent grade 1 or grade 2 toxicities were elevated creatinine, ALT elevation, hypokalemia, lymphopenia, and fatigue. Grade 3 events included cytopenia (n = 5), AST/ALT elevation (n = 3), asymptomatic hypophosphatemia (n = 2), pain (n = 1), and renal failure (n = 1). One patient experienced grade 4 lymphopenia without associated infection. One patient developed renal failure characterized by grade 3 creatinine elevation and grade 4 hyperkalemia, which resolved to grade 1 creatinine elevation.

TABLE 2.

Nonhematologic Toxicities (Possible, Probable, or Definite Attribution to Drug)

| Adverse Event | Grade 1–2, Number (%) | Grade 3, Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | ||

| Anorexia | 3 (25) | 0 |

| Chills/rigors | 3 (25) | 0 |

| Diaphoresis | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 5 (42) | 0 |

| Fever | 3 (25) | 0 |

| Weight loss | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Diarrhea | 3 (25) | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Mucositis | 2 (17) | 0 |

| Nausea | 4 (33) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Neurologic | ||

| Ataxia | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Pain | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Taste alteration | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Other | ||

| Dry skin | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Pruritis | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Rash | 2 (17) | 0 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 1 (8) |

TABLE 3.

Hematologic and Biochemical Adverse Events (Possible, Probable, or Definite Attribution to Drug)

| Adverse Event | Grade 1–2, Number (%) | Grade 3, Number (%) | Grade 4, Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myelosuppression | |||

| Anemia | 4 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 2 (17) | 2 (17) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 5 (42) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Platelets | 4 (33) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| PTT | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Liver enzyme elevations | |||

| ALT | 7 (58) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| AST | 2 (17) | 2 (17) | 0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Alterations in serum chemistries | |||

| Hyponatremia | 4 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypernatremia | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 5 (42) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Elevated creatinine | 7 (58) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 3 (25) | 2 (17) | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

DISCUSSION

Although preclinical data has demonstrated significant xenograft antitumor activity in a spectrum of solid tumors and a potential role of Bcl-2 in MCC has been identified, no PR or CRs were observed in this phase II trial of the novel antisense bcl-2 G3139 (Genasense) administered at specific dose and schedule in patients with advanced MCC. It is important to note that the patient population in the present study reflects the typical referral pattern to cancer centers in that most patients are referred after having failed first line systemic therapy. It is possible that the toxicity profile and responses might be different if G3139 was administered to chemo-naive patients. Overall, G3139 treatment was well tolerated, exhibiting manageable toxicities including transient AST/ALT elevation, fatigue, elevated serum creatinine, lymphopenia, hypophosphatemia, and hypokalemia, in keeping with other reports in the literature.

The best response in this study was SD of transient duration in 3 patients. The choice of an appropriate end point for the assessment of response to biologic therapies is a challenging problem. Previous studies have shown that the use of RECIST criteria for the evaluation of response to biologic therapies is probably not optimal because biologic therapies may act through mechanisms other than cell death. Treatment with biologic therapy may lead to necrosis and development of cystic areas within tumors, with little measurable decrease in overall tumor size by traditional unidimensional measurement criteria. For example, previous studies have demonstrated that RECIST using only tumor size is unreliable for the monitoring of gastrointestinal stromal tumors during treatment with imatinib mesylate.26,27 Choi et al27 demonstrated that in a group of 40 patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors, the criteria of decrease in tumor size of more than 10% or decrease in tumor density of more than 15% on CT had sensitivity and specificity of 97% and 100%, respectively, in predicting positron emission tomography responders. This was subsequently validated in a second group of 58 patients.28 Similarly, Ratain et al29 have shown that traditional dimensional criteria per RECIST were not able to accurately identify response of renal cell cancer to sorafenib treatment.

Antisense Bcl-2 is believed to stimulate apoptosis, to inhibit angiogenesis, and to exert immunostimulatory effects. However, methods of quantifying response in terms of these mechanisms are not currently standardized, and radiologic response remains one of the most universal outcome measurements. The clinical response of patient 004 illustrates the difficulty of using RECIST for outcome measurement. Although the patient did demonstrate response as evidenced by disappearance of 1 of 2 metastases (the scalp metastasis) and necrosis of the other metastasis (the adrenal metastasis), the radiologic response had to be classified as SD per the predefined criteria. Further support for the response of this patient to therapy was the strong positivity of immunohistochemical staining of viable tumor tissue for Bcl-2. It is possible that G3139 treatment caused tumor hemorrhage in the adrenal metastatic mass, resulting in an increase in size on CT scan, whereas the scalp metastasis disappeared because of antitumor effect of G3139. It is also noteworthy that the patient has remained in complete remission for 22 months after 2 cycles of G3139 and surgical resection. It is unclear whether there were particular pharmacokinetic or pharmacogenomic factors or tumor genetics unique to patient 004 that might explain such an interesting response. It is possible that strong Bcl-2 positivity in the tumor contributed to the antitumor activity of G3139 in this case. Pre- and on-therapy tumor biopsies to evaluate the effect on down- regulation of Bcl-2 as a result of G3139 therapy were planned as optional studies on this trial. However, because of visceral sites of metastasis, urgency of need to start systemic therapy for rapidly growing MCC and patient preference, paired biopsies were not done in any of the patients.

A previously reported phase I trial of single-agent G3139 in patients with advanced cancer revealed no responses. The most common toxicities were fatigue and transient transaminase elevation.24 In a study of single agent G3139 in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PR was observed in 2 of 26 patients.30 A phase I study of G3139 combined with the 7 + 3 regimen in patients with acute myelocytic leukemia produced CR in 14 of 29 patients.31 However, a subsequent phase III trial found no benefit to adding G3139 to chemotherapy in acute myelocytic leukemia.32 Several other phase I trials of G3139 combined with chemotherapy for diverse malignancies have demonstrated PRs in 5% to 86% of patients.33–35 Reported toxicities including febrile neutropenia, nausea, vomiting, fever, fatigue, transaminase elevation, and prolongation of a PTT were consistent with the toxicities observed in the present trial. Phase II trials of G3139 in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy have similarly demonstrated promising results in various malignancies.36–37 Finally, there is an ongoing cancer and leukemia group B phase II study of G3139 in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Given that MCC and SCLC fall into the same part of the spectrum of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine cancers, further evaluation of the activity of G3139 in MCC may be considered depending on the results of the SCLC study.

Our multicenter trial of G3139 in a rare cancer such as MCC demonstrates the feasibility of completing a phase II trial using this drug. There are several possible reasons for the lack of clinical activity in this trial. It is possible that this dose or treatment regimen did not produce optimal Bcl-2 target inhibition. Morris et al,23 in a phase I trial of G3139 in 35 patients with advanced cancers, established that G3139 has a half-life of 2 hours and achieves steady state by 10 hours, and that plasma concentrations increase linearly with dose up to 6.9 mg/kg/d. Although there is no clear reason why PK and target bcl-2 inhibition would be altered in MCC cells, we were not able to demonstrate activity of single-agent G3139 at the optimal dose of 7 mg/kg/d in this study. Although the intent was to obtain tissue biopsies after treatment with G3139, the majority of patients had visceral metastases and tissue was not available. Thus, target inhibition was not directly verified. In addition, 6 patients required dose reductions, and therefore may have attained suboptimal drug concentrations. In summary, although antisense bcl-2 therapy G3139 (Genasense) was well tolerated in patients with metastatic or regionally recurrent MCC, no PR or CRs per protocol- specified criteria were observed. Although probable antitumor activity was documented in 1 patient, no objective responses per protocol-specified criteria were observed.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA63185.

References

- 1.Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300–2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489–1495. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, et al. Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:204–208. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karakousis CP, Balch CM, Urist MM, et al. Local recurrence in malignant melanoma: long-term results of the multiinstitutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:446–452. doi: 10.1007/BF02305762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veness MJ, Morgan GJ, Gebski V. Adjuvant locoregional radiotherapy as best practice in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2005;27:208–216. doi: 10.1002/hed.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meeuwissen JA, Bourne RJ, Kearsley JH. The importance of postoperative radiation therapy in the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)E0145-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison WH, Peters LJ, Silvia EG, et al. The essential role of radiation therapy in securing locoregional control of Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:583–591. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al. High risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group study-TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371–4376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mojica P, Smith D, Ellenhorn JD. Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1043–1047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Psyrri A, et al. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:780–785. doi: 10.1080/07357900601062354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I, et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk Stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feun LF, Savaraj N, Lehga SS, et al. Chemotherapy for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Review of the MD Anderson Hospital’s experience. Cancer. 1988;62:683–685. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880815)62:4<683::aid-cncr2820620406>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raaf JH, Urmacher C, Knapper WK, et al. Trabecular (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: treatment of primary, recurrent, and metastatic disease. Cancer. 1986;57:178–182. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860101)57:1<178::aid-cncr2820570134>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George TK, di Sant’agnese PA, Bennett JM. Chemotherapy for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1985;56:1034–1048. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<1034::aid-cncr2820560511>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma D, Flora G, Grunberg SM. Chemotherapy of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:166–169. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wynne CJ, Kearsley JH. Merkel cell tumor. A chemosensitive skin cancer. Cancer. 1988;62:28–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880701)62:1<28::aid-cncr2820620107>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsujimoto Y, Cossman J, Jaffe E, et al. Involvement of the bcl-2 gene in human follicular lymphoma. Science. 1985;228:1440–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.3874430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mita M, Tolcher AW. Novel apoptosis inducing agents in cancer therapy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2005;29:8–32. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolcher AW. Targeting Bcl-2 protein expression in solid tumors and hematologic malignancies with antisense oligonucleotides. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2005;3:635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim R, Emi M, Matsuura K, et al. Antisense and nonantisense effects of antisense Bcl-2 on multiple roles of Bcl-2 as a chemosensitizer in cancer therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:1–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlagbauer-Wadl H, Klosner G, Heere-Ress E, et al. Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotides (G3139) inhibit Merkel cell carcinoma growth in SCID mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:725–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris MJ, Tong WP, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Phase I trial of BCL-2 antisense oligonucleotide (G3139) administered by continuous intravenous infusion in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:679–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen B, Wacheck V, Heere-Ress E, et al. Chemosensitization of malignant melanoma by BCL2 antisense therapy. Lancet. 2000;356:1728–1733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi J, Charnsangavej C, de Castro Faria S, et al. CT evaluation of the response of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after imatinib mesylate treatment: a quantitative analysis correlated with FDG PET findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1619–1628. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi H, Chatnsangavej C, Faria SC, et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastro-intestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1753–1759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamin RS, Choi H, Macapinlac HA, et al. We should desist using RECIST, at least in GIST. J Clin Oncol. 2007;13:1760–1764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratain MJ, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2505–2512. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Brien SM, Cunningham CC, Golenkov AK, et al. Phase I to II multicenter study of oblimersen sodium, a Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide, in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7697–7702. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcucci G, Stock W, Dai G, et al. Phase I study of oblimersen sodium, an antisense to Bcl-2, in untreated older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical activity. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3404–3411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcucci G, Moser B, Blum W, et al. A phase III randomized trial of intensive induction and consolidation chemotherapy ± oblimersen, a pro- apoptotic Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide in untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients > 60 years old. J Clin Oncol 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I Vol. 2007;25(18S):7012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mita MM, Ochoa L, Rowinsky EK, et al. A phase I, pharmacokinetic and biologic correlative study of oblimersen sodium (Genasense™, G3139) and irinotecan in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:313–321. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall J, Chen H, Yang D, et al. A phase I trial of a Bcl-2 antisense (G3139) and weekly docetaxel in patients with advanced breast cancer and other solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1274–1283. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudin CM, Kozloff M, Hoffman PC, et al. Phase I study of G3139, a bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide, combined with carboplatin and etoposide in patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1110–1117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bedikian AY, Millward M, Pehamberger J, et al. Bcl-2 antisense (oblimersen sodium) plus dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma: the oblimersen melanoma study group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4738–4745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tolcher AW, Chi K, Kuhn J, et al. A phase II pharmacokinetic and biological correlative study of oblimersen sodium and docetaxel in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3854–3861. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]