Abstract

The Medical Council of India has set appropriate and relevant objectives to train each medical student into a basic doctor for the country. Even though they envisage that these basic doctors would work as physicians of first contact, providing for the health needs of India at primary and secondary care level, the site of training and the context of clinical teaching do not seem to empower the students to become a basic doctor. ‘Vision 2015’, the document written by the board of governors of medical council of India suggests reforms in medical education such as early clinical exposure, integration of principles of family medicine, and clinical training in the secondary care level. Family medicine training with trained family medicine faculty might add this missing ingredient to our basic doctor training. This article discusses the role of family medicine in undergraduate medical training. We also propose the objectives of such training, the structure of the training process, and the road blocks with possible solutions to its implementation.

Keywords: Family Medicine, India, undergraduate medical training

Introduction

The Medical Council of India (MCI) is regulating the undergraduate medical education in India in 362 medical colleges that are able to train 45,629 medical students annually.[1] The Graduate medical curriculum, proposed by MCI, is oriented toward training students to undertake the responsibilities of a physician of first contact who is capable of looking after the preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative aspects of medicine.[2] MCI envisages the graduate doctors to be competent in diagnosis and management of common health problems of the individual and the community, commensurate with his/her position as a member of the health team at the primary, secondary, or tertiary levels, using his/her clinical skills based on history, physical examination, and relevant investigations.[3]

Even though India has the highest number of medical colleges in the world and known for health tourism across the world, there is shortage of doctors in primary care in India.[4] Only half of the deliveries happen under the supervision of trained health attendant and only 36% of children under 12 months are fully immunized, leading to unacceptably high maternal and infant deaths in the country.[5] There is a tendency among the doctors to pursue specialization in India or to move abroad after their UG training.

Board of Governors’ of Medical council of India has recommended in their document ‘Vision 2015’ about ‘giving emphasis for training in primary and secondary care level with compulsory family medicine training’ and also recommend integration of principles of family medicine into the existing curriculum. They recommend that the focus of the clinical training should be on common problems seen in out-patient and emergency setting.[4] This paper discusses gaps in the current medical education in India and the possible role of family medicine in addressing the gaps in undergraduate medical education.

Who is a family physician?

A family physician (FP) is placed in primary- or secondary-care centers as a specialist clinician and provides first contact and continuity of care to all the individuals in a defined population, without any limitations of age, sex, organ, or disease. She/he is an expert in managing undifferentiated illness, manages multiple problems in the same patient either acute or chronic problem, be it a preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative, or palliative care.[6] FP is an expert in providing whole person care by taking care of the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health with consideration to the patients’ fears and concerns about his/her health issues. FP continues and coordinates the care when referral to multiple specialists is needed.

Current training in tertiary care

Graduate Medical Education happens mostly in tertiary care environment in medical colleges in India. Out of the 142 weeks of clinical rotation, 91.5% of the time is spent in tertiary care.[2] Tertiary care has the advantage of plenty of teaching materials, faculty, and role models in specialist care for the students but has few disadvantages with regard to the objectives of undergraduate medical education.

Most of the patients attending tertiary-care institutions have more complex illnesses and rare health problems. While this can be used for competencies in history taking and examination skills, exposure to the diagnosis and management of common illnesses is ignored. As the probability of complicated and complex illnesses increases, diagnosis in tertiary care is mostly based on investigations. More tests are done to rule out rare diseases as possible diagnoses. This helps a student to identify rare illnesses but investigations for symptoms become the norm. However, the physicians are expected to work in primary and secondary care areas after the UG training. The students translate tertiary care practices to the primary care areas leading to increased cost and inappropriate care.

In tertiary care there is fragmented care for patients with multiple problems by different specialties; students have less opportunity to see and learn how to provide care for multiple problems in a given patient. For example, when an elderly person is admitted with uncontrolled diabetes, congestive heart failure, and osteoarthritis, the patient is managed by a team of physicians including internist, geriatrician, cardiologist, orthopedist, and endocrinologist in tertiary care. The students when faced with similar problems during their practice, they are not empowered to manage in primary care but learn to refer more than to resolve it in primary care.

Further in tertiary care settings, mostly acute, episodic, curative care is practiced and taught. There are lesser chances for the students to learn continuity of care and rehabilitation after the acute illness is treated. They become only ‘problem-fixers’ rather than health promoters and disease preventers. Health promotion and disease prevention is seen less glamorous as opposed to curative care.

In tertiary care, the student learning happens in the hospital context with less community orientation. Community orientation here means applying the knowledge of the diseases in the community that is served by any particular hospital. Community orientation[7] involves the following issues: Identify important characteristics of the local community that might impact upon patient care such as community health needs, local prevalence of diseases, recognizing local community resources for patient care etc.; identify important elements of local health care provision in hospital and in the community; identify how the limitations of local healthcare resources might impact upon patient care; optimize the use of limited resources, for example through cost-effective prescribing.

This discrepancy between training site and workplace may lead to inappropriate health-care delivery, more referrals and poor image of primary health care. Because of the lack of confidence to work in primary health care, the graduate doctors tend to do further specialization or move abroad.

Current training in primary care

Currently the students are posted in primary care as a part of community medicine rotation for 12 weeks out of 142 weeks of clinical rotations.[2] In most of the medical colleges community medicine teaching is ‘non clinical’ that includes epidemiology, public health, preventive, and social medicine. Students perform surveys and projects in the community to understand the risk factors which cause the disease. Only during internship, the students are posted in community health centers to get exposed to the clinical work in primary care. It will be ideal to sensitize the students to the clinical care in primary care through family medicine approach during their early clinical years that can be reinforced during the internship.

Proposed UG Curriculum for Family Medicine Training in India

Broad objectives of family medicine training in UG teaching

At the end of family medicine training, the student will

have the knowledge and skills to manage common outpatient and emergency problems at the level of primary and secondary care

be able to provide health care in the context of the family and the local community

be able to integrate principles of family medicine in their day to day interaction with patients.

Content

Consultation skills

Personal care, primary care, continuing care, and comprehensive care

Health promotion in consultation

Emergency care and house calls

Family as a unit of care

Care of the elderly

Palliative care.

Common symptoms

Management of following common symptoms can be taught to UG students in family medicine rotation:

Abdominal pain

Abnormal uterine bleeding

Arthritis

Back pain

Chest pain

Cough

Constipation

Depression

Dyspepsia

Dyspnea

Diarrhea

Ear discharge

Edema legs

Faints and fits

Fever

Fatigue

Falls in elderly

Headache

Insomnia

Incessantly crying baby

Red eye

Skin rash

Urinary Symptoms

Vaginal discharge

Vomiting

Weakness of the limbs

Weight gain and loss

Common procedures

History taking for above symptoms

Physical Examination including examination of ENT, Eye, Obstetric, Gynecological, Medical and Surgical conditions for adults, elderly and children

Interpretation of X-ray, ECG, EEG, EMG, NCV and Spirometry

Intra muscular, intravenous and intra-articular injections

Incision and drainage of abscesses

Ear lobe repair

Nebulization for asthma and COPD

Explaining the use of inhaler and nebulizer device

Excision and biopsy of swellings

Suturing of wounds

Wound dressing

Wound debridement

Syringing of the ear for wax

Removing of foreign bodies from ear, nose and eye

Packing of the nose in epistaxis

POP application of common fractures like clavicle and colles

Conduct of normal delivery and management of third stage

New born care

IUCD insertion

Counseling.

Training site

The recommended training site is the ‘family practice center’ run by the family medicine department. If the medical college does not have the functioning family medicine department, the primary or community health center or First referral unit attached to the medical college can be used.

Faculty

Faculty qualifications: MD in family medicine, general medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, community medicine, and general surgery. They must be working one of the following training sites attached to medical college; family practice center, primary health center, community health center or First referral unit.

Faculty who are teaching family medicine should undergo training in the principles of family medicine and teaching of this discipline through faculty development workshop.

Structure of postings in family medicine:

I year - ½ day per week for 24 weeks

II year - 4 weeks (half day)

III year - 4 weeks (full day)

Internship - 4 weeks (full day)

Objectives, teaching methods and assessment methods

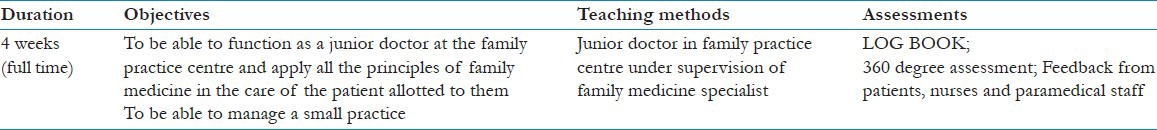

Discussion

The traditional medical curriculum encourages learning extensive factual knowledge with focus on hospital-based and disease-centered medicine that is deficient in problem solving skills. There is less emphasis for rational and cost-effective management of the common clinical problems.[8] In contrast, family medicine training is based on problem solving skills in primary care environment with rational use of investigations and cost-effective management. Through family medicine training, students are likely to learn how they can apply their clinical knowledge gained in tertiary care to primary and secondary care context. Inclusion of internship in family medicine will help us to achieve this objective [Table 1].

Table 1.

Family medicine rotation in internship

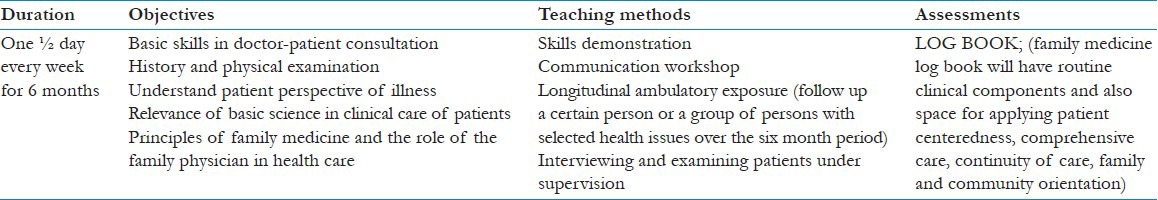

Integration of the learning in basic sciences with the clinical sciences has been suggested in Vision 2015[4] as well as by other medical educators across the country.[8,9] Family medicine rotation in first year [Table 2] would give opportunity to apply the basic sciences knowledge into clinical medicine. For example, when they learn cardio vascular system in physiology and anatomy, they see a patient with heart failure in this rotation.

Table 2.

Family medicine rotation in first year

Students also have an opportunity to observe the role of the basic doctor which would prepare them for the clinical rotations. The students will follow-up few families where one of the family members is visiting the practice, over 24 weeks during this rotation. This is an opportunity for the students to see ‘Continuity of care or Follow-up’ which is not taught in the current curriculum.

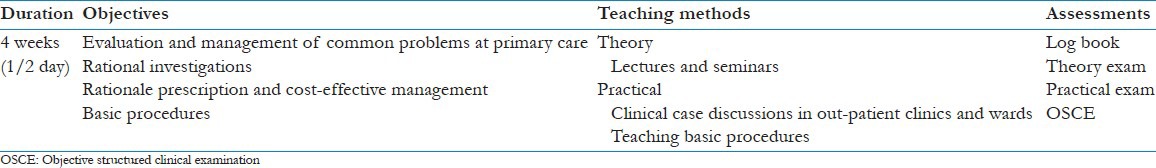

In second year, the students come to family medicine, after finishing the main postings in medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and obstetrics. [Table 3] They will discuss the diagnosis and management of common problems in primary care with the available resources. For example, management of pneumonia is discussed in both medicine and family medicine postings, but the context is different. In tertiary care students see more complicated pneumonia, referred to tertiary care, who are managed in ICU setting with pulse oximeter and availability of ventilator in case of respiratory failure. In family medicine the students will be taught how to diagnose and manage with the available resources in primary care and when to refer to tertiary care. Community-based clinical learning experiences might positively influence their learning outcomes to train them as first contact physician.[9]

Table 3.

Family medicine rotation in second year

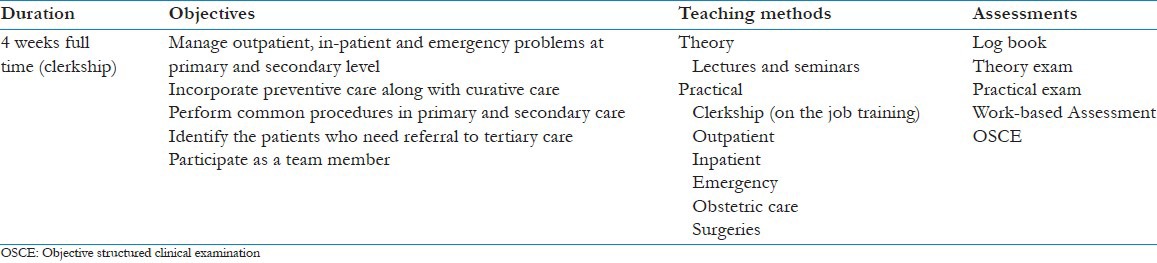

Early clinical exposure in a community-based setting is lacking in Indian medical curriculum. The students have the hands-on training opportunity only in their internship which would negatively affect their learning.[9] A clerkship model of training in Family Medicine for final year students [Table 4] can fill this gap.[8]

Table 4.

Family medicine rotation in final year

Expected outcomes

Currently after the MBBS training, most of the doctors choose either to go for specialization or to work abroad. But only 22,503 PG seats are available for 45,629 UG doctors produced every year.[1] The remaining doctors either work in primary care or go abroad to pursue specialization. Even though there is huge need in primary or secondary care in India, the graduates do not see that as a career. By introducing family medicine education in the UG training, there is a possibility of empowering the students to work in primary care. The students can see family physicians as ‘role models’ and have a better image of primary care. Family medicine training is one of the many solutions for making the medical education more relevant to the needs of the country.

Road blocks for implementation

Family medicine training cannot be implemented immediately because of lack of the family medicine faculties and family medicine practice services in medical colleges. As the medical council of India has not included family medicine in the graduate curriculum, very few medical colleges have family physicians in their faculty list. The current UG curriculum is fully packed with many specialties and it is a challenge to introduce a new specialty. It may not be possible to introduce it all years at one time, but it is feasible to introduce in the step-wise manner.

Conclusion

Family medicine is a specialty that adds the missed ingredient in the current undergraduate medical education in India. We suggest Medical Council of India to consider implementing family medicine training in undergraduate medical education.

Acknowledgement

We Acknowledge Dr. Anand Zachariah, Professor of Medicine, Christian Medical College, Vellore, for his in-put in to the development of the proposed UG curriculum for family medicine.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Raghavan MK. Medical Colleges; [Last cited in 2014 Jun 11]. Government of India Ministry of health and Family Welfare, starred question no 37 answered on 23.11.2012. Available from: http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/psearch/QResult15.aspx?qref=130114 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medical Council of India. Graduate Medical Education Regulations, 1997 [Internet] 1997. [Last cited in 2014 Jun 14]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/GraduateMedicalEducationRegulations1997.aspx .

- 3.Medical Council of India regulations on graduate medical education. 1997. [Last cited in 2014 Jun 14]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/Rules-and-Regulation/GME_REGULATIONS.pdf .

- 4.MCI book.p65-MCI_booklet.pdf. [Last cited in 2014 Jul 4]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/tools/announcement/MCI_booklet.pdf .

- 5.Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. India Country Report, 2013; Statistical Appraisal, SAARC Development Goals. Government of India. 2013. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 14]. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/SAARC_Development_Goals_%20India_Country_Report_29aug13.pdf .

- 6.Phillips WR, Haynes DG. The domain of family practice: Scope, role, and function. Fam Med. 2001;33:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marr C, Rughani A. Introduction to the Site: Workplace Based Learning for General Practice [Internet] Community Orientation. [Last cited in 2014 Jul 02]. Available from: http://www.wpba4gps.co.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/secure/mindmaps/PDF_files_for_Competency/Community_Orientation.pdf .

- 8.Sood R, Adkoli BV. Medical education in India – Problems and prospects. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2000;1:210–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayakrishnan T, Honhar M, Jolly GP, Abraham J, T J. Medical education in India: Time to make some changes. Natl Med J India. 2012;25:164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]