Abstract

Introduction:

The world's population is aging quickly, leading to increased challenges of how to care for individuals who can no longer independently care for themselves. With global social and economic pressures leading to declines in family support, increased reliance is being placed on community- and government-based facilities to provide long-term care (LTC) for many of society's older citizens. Complementary and integrative healthcare (CIH) is commonly used by older adults and may offer an opportunity to enhance LTC residents' wellbeing. Little work has been done, however, rigorously examining the safety and effectiveness of CIH for LTC residents.

Objective:

The goal of this work is to describe a pilot project to develop and evaluate one model of CIH in an LTC facility in the Midwestern United States.

Methods:

A prospective, mixed-methods pilot project was conducted in two main phases: (1) preparation and (2) implementation and evaluation. The preparation phase entailed assessment, CIH model design and development, and training. A CIH model including acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapy, guided by principles of collaborative integration, evidence informed practice, and sustainability, was applied in the implementation and evaluation phase. CIH services were provided for 16 months in the LTC facility. Quantitative data collection included pain, quality of life, and adverse events. Qualitative interviews of LTC residents, their family members, and LTC staff members queried perceptions of CIH services.

Results:

A total of 46 LTC residents received CIH care, most commonly for musculoskeletal pain (61%). Participants were predominantly female (85%) and over the age of 80 years (67%). The median number of CIH treatments was 13, with a range of 1 to 92. Residents who were able to provide self-report data demonstrated, on average, a 15% decline in pain and a 4% improvement in quality of life. No serious adverse events related to treatment were documented; the most common mild and expected side effect was increased pain (63 reports over 859 treatments). Qualitative interviews revealed most residents, family members and LTC staff members felt CIH services were worthwhile due to perceived benefits including pain relief and enhanced psychological and social wellbeing.

Conclusion:

This project demonstrated that with extensive attention to preparation, one patient-centered model of CIH in LTC was feasible on several levels. Quantitative and qualitative data suggest that CIH can be safely implemented and might provide relief and enhanced wellbeing for residents. However, some aspects of model delivery and data collection were challenging, resulting in limitations, and should be addressed in future efforts.

Key Words: Long-term care, complementary and integrative healthcare, pilot, elderly, quality of life, wellbeing

摘要

简介:世界人口迅速老龄化,导 致如何照顾那些不能再独立照顾 自己的老人的挑战日益严峻。随 着全球社会和经济压力,导致家 庭赡养能力下降,更多依赖以社 区和政府为基础的设施,为许多 社会的老年公民提供长期护理 (LTC)。老年人经常使用补充和 综合医疗保健(CIH),CIH 并可 能提供一个机会以改善 LTC 居民 的福祉。然而,针对 LTC 居民的 CIH 安全性和有效性而进行的严格 检验不多。

目的:这项工作的目标是描述一 个试点项目,以开发和评估一个 在美国中西部的 LTC 设施的 CIH 模型。

方法:前瞻性、混合方法试点项 目主要分两个阶段进行:(1)准 备和(2)实施和评估。准备阶段 牵涉到评估、CIH 模型设计和开发 以及培训。一个 CIH 模型包括针 灸、整脊、按摩疗法,通过协同 整合、证据告知做法和可持续发 展的原则为指导,在实施和评估 阶段进行应用。该 LTC 设施提供 了 CIH 服务 16 个月。定量数据 收集包括疼痛、生活质量和不良 反事件。与 LTC 居民、其家庭成 员和 CIH 服务看法查询的 LTC 工 作人员进行定性访谈。

结果:一共有 46 位 LTC 居民进 行了 CIH 护理,肌肉骨骼疼痛护 理(61%)最为普遍。参与者以女 性(85%)和 80 岁以上 (67%) 为主。CIH 治疗的中位数是 13, 范围是 1 到 92。居民们能够提供 自我报告的数据表明 , 平均来 看,15% 减轻了疼痛且 4% 改善了 生活质量。没有与治疗相关的严 重不良事件记录在案;最常见的 轻度和预期副作用是疼痛增加 (859 例治疗中有 63 份报告)。 定性访谈显示,大多数居民、家 庭成员和 LTC 工作人员认为:由 于感知的益处(包括缓解疼痛、 增强心理和社会福祉),因此 CIH 服务是值得的。

结论:这一项目表明,广泛关注 准备工作,一个以患者为中心的 CIH 模型在 LTC 在几个层面上是 可行的。 定量和定性数据表 明,CIH 可以安全地实施并且可为 居民减轻疼痛和增加福祉。 然而,模型传递和数据收集的某些 方 面 都具有挑战性,造成局限性,应在今后的工作中解决。

SINOPSIS

Introducción: La población mundial envejece con rapidez, lo cual lleva a mayores retos sobre cómo atender a individuos que no pueden cuidarse a sí mismos de manera independiente. Dado que la presión global social y económica va llevando a la disminución del apoyo a la familia, se aumenta la confianza en la comunidad y en las instalaciones respaldadas por la Administración para proporcionar atención a largo plazo a muchos de los ciudadanos mayores de la sociedad. La atención sanitaria complementaria e integral es usada por lo general por personas mayores y puede ofrecer una oportunidad para mejorar el bienestar de los residentes de atención a largo plazo. Pocos esfuerzos se han hecho, sin embargo, para examinar con rigurosidad la seguridad y efectividad de la atención sanitaria complementaria e integral para residentes de atención a largo plazo.

Objetivo: El objetivo de este trabajo es describir un proyecto piloto para desarrollar y evaluar un modelo de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral en una instalación de atención a largo plazo en el Medio Oeste de los Estados Unidos.

Métodos: Se llevó a cabo un proyecto piloto prospectivo, de métodos mixtos en dos fases principales: (1) preparación e (2) implementación y evaluación. La fase de preparación conlleva la valoración, el diseño y desarrollo del modelo de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral, y la formación. Se aplicó un modelo de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral que incluye acupuntura, quiropráctica y terapia de masaje, según los principios de integración colaboradora, práctica informada según evidencias y sostenibilidad en las fases de implementación y evaluación. Los servicios de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral se proporcionaron durante 16 meses en la instalación de atención a largo plazo. La recolección de datos cuantitativos incluyó los relativos al dolor, calidad de vida y acontecimientos adversos. Las percepciones de los servicios de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral se indagaron mediante entrevistas cualitativas de los residentes de atención a largo plazo, sus familiares y los miembros del personal.

resultados: Un total de 46 residentes de atención a largo plazo recibieron atención sanitaria complementaria e integral, sobre todo por dolor musculoesquelético (61%). Los participantes fueron predominantemente mujeres (85%) y mayores de 80 años (67%). El número medio de tratamientos de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral fue de 13, con un rango de 1 a 92. Los residentes capaces de proporcionar datos propios por sí mismos mostraron, de media, un 15% de disminución del dolor y un 4% de mejora de calidad de vida. No se documentaron acontecimientos adversos graves relacionados con el tratamiento; el efecto secundario más común, leve y esperado fue el de aumento del dolor (63 notificaciones de 859 tratamientos). Las entrevistas cualitativas revelaron que la mayoría de los residentes, familiares y miembros del personal de atención a largo plazo opinaron que los servicios de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral merecen la pena debido a los beneficios percibidos, incluyendo el alivio del dolor y la mejora del bienestar psicológico y social.

Conclusión: El proyecto demostró que, con una gran atención en la preparación, un modelo centrado en el paciente de atención sanitaria complementaria e integral en atención a largo plazo era viable a varios niveles. Los datos cuantitativos y cualitativos sugieren que la atención sanitaria complementaria e integral puede implementarse con seguridad y podría proporcionar alivio y bienestar acentuado a los residentes. Sin embargo, algunos aspectos de la presentación del modelo y la recopilación de datos fueron un reto, dando lugar a limitaciones, que deberían afrontarse en futuros intentos.

INTRODUCTION

The world's population is rapidly aging, and issues surrounding how to best care for its older inhabitants has become a global concern.1 An estimated 1.5 billion individuals are projected to reach 65 years of age or older by 2050, and the oldest old (ages 85 and older) represent the fastest growing segment of many countries' populations.1-3

Inevitably, advancing age is accompanied by issues of how to care for individuals who can no longer independently care for themselves. While many older people prefer to remain in their own homes and communities as they age, declining health and function often limit their ability to do so.3 Global social and economic trends are resulting in increased numbers of aging individuals with little or no family support.3 Indeed, long-term care for older adults has become a well-recognized challenge in developed Western nations as well as in less developed countries.1

Societies worldwide are in need of ways to safely and sustainably ensure the health and wellbeing of their aging citizens.3 In the United States, there are nearly 43 million people aged 65 years and older.4 The US Department of Health and Human Services reports that nearly 70% of the current older population will need long-term care services ranging from home care visits to long-term care (LTC).5 American LTC residents suffer from a variety of chronic and degenerative health conditions including pain, depression, and dementia.6 Importantly, two-thirds of LTC residents receive psychoactive medication, and more than 45% receive pain medication,6 leading to concerns of drug-drug interactions and adverse drug effects.7,8 Additionally, the fact that older individuals often have multiple comorbidities further complicates treatment choices and quality of care.9

The economic cost of addressing older individuals' health needs is substantial. In 2012, more than $151 billion was spent on formal LTC services including skilled nursing facilities and retirement communities in the Untied States.10 While government-supported Medicare and Medicaid are available, not all residents qualify for Medicaid because they have other financial resources, and Medicare does not pay for many LTC services.11 With the average cost of LTC at approximately $200/day per resident,11 this leaves many older people and/or their families carrying a considerable economic burden.12 The costs of LTC are more than financial. For individuals residing in LTC these can include potential losses of autonomy, dignity, respect, and quality of life (QOL).13

Complementary and integrative healthcare (CIH) services pose a unique opportunity to decrease some of the burden associated with LTC. CIH is most frequently applied to some of the most common ailments suffered by LTC residents and with relatively few side effects.9,14-16 Up to 40% of older adults report CIH use in the United States17; however, there has been little work describing the use of CIH by LTC residents.18

The purpose of this article is to describe a pilot project to develop and evaluate one model of CIH to enhance wellbeing of residents in an LTC facility in the midwestern United States. The specific goals of the pilot study were to (1) develop a potential model of CIH that would address the needs of LTC residents; (2) explore the feasibility of implementing the model in a LTC facility; (3) assess the feasibility of collecting outcomes data to evaluate CIH for LTC residents; and (4) describe preliminary data regarding CIH implementation in LTC.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective, mixed-methods pilot project conducted by investigators formerly based at Northwestern Health Sciences University (NWHSU) in collaboration with the Volunteers of America. NWHSU is located in Bloomington, Minnesota, and is home to 3 CIH professional academic programs in chiropractic, acupuncture, and massage therapy. The Volunteers of America is a nonprofit, faith-based social welfare organization that provides services to underserved groups including the elderly and has several LTC facilities in the Minneapolis metropolitan area. The project was approved by NWHSU's institutional review board and took place at a 125-bed Volunteers of America facility; 89 of the 125 beds were dedicated to LTC. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (individual or through a healthcare proxy). The project was conducted in two main phases: (1) preparation and (2) implementation and evaluation.

Phase I: Preparation

Since CIH services were new to the LTC facility, extensive consideration was given to addressing the necessary preparations to introduce CIH services with minimal disruption to facility residents, staff, and management. Preparation took place over a 9-month period and focused on assessment, model design and development, and training. More than 30 individuals from the two participating institutions representing leadership, management, healthcare providers, and staff were involved in at least one aspect of the preparation phase.

Assessment

Initial meetings were conducted between investigators and LTC facility management to assess needs of the LTC facility and its residents and to establish resource availability. Additional meetings were conducted between investigators, NWHSU academic administrators, and CIH professionals to learn more about CIH scope of practice and assess training needs of CIH providers and LTC staff. Literature searches were conducted regarding effectiveness and safety of specific CIH modalities to inform protocol design and training.

CIH Model Design & Development

An iterative process led by the project director (KW) was used to develop a LTC CIH model that took into account initial assessments and the project goals.

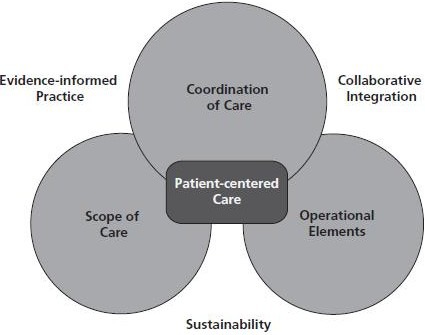

LTC and CIH team members mobilized around a primary objective of providing patient-centered care that would be guided by the principles of collaborative integration,19 evidence-informed practice,20 and sustainability. This provided the context for developing key features of the care model, including scope of care, coordination of care, and operational elements (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model of complementary and integrative healthcare in long-term care.

Scope of Care. The focus of treatment was to ensure patient safety and comfort. This would be accomplished by orienting care toward the most conservative treatment modalities first; providing gentle treatment of short duration to patients' tolerance; and modifying treatment as necessary based on patients' response. Three CIH professions were included in this model: acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapy. Specific CIH treatment modalities used by these CIH professions were reviewed to identify those that best fit criteria for safe, evidence-informed geriatric care. Treatments with theoretically greater potential for risk—although perhaps without solid evidence of harm in the frail elderly—were excluded as a precautionary principle for the duration of this project. For example, herbal remedies were not allowed due to the potential for negative drug-herb interactions. Pain and associated manifestations including sleep disturbance, decline in physical function, and behavior changes (eg, agitation or depression) were deemed appropriate for CIH care services. Table 1 details the specific treatment modalities included in and excluded from the CIH model for each of the CIH professions.

Table 1.

Complementary and Integrative Healthcare (CIH) Treatment Modalities Included in and Excluded From the CIH Model

| CIH profession | Included treatment Modalitiesa (definitions) | Excluded treatment Modalities (rationale) |

|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture | ||

| Acupuncture (the insertion of fine disposable sterilized needles through the skin to channel and non-channel points on the body) | Herbs (potential for herb-drug interaction) | |

| Acupressure (manual pressure applied to channel and non-channel points on the body) | Moxibustion (potential for burns) | |

| Tui Na (body work using manually applied compressions to soft tissue) | Heat lamp (potential for burns) | |

| Qigong (breathing exercises) | ||

| Chiropractic | ||

| Manipulation and mobilization (manual application of a careful movement or push to a joint) | Ultrasound (potential for burns) | |

| Soft tissue work (manual pressure applied to muscles and fascia) | ||

| Hot pack (application of heat to the body through the use of hydrocollator pads wrapped in towels) | ||

| Active muscle stretching (stretches performed by the patient with or without assistance of the provider) | ||

| Passive muscle stretch (stretches performed by the provider without assistance from the patient) | ||

| Supervised exercise (strength, motion, and balance exercises performed under the instruction and supervision of the provider) | ||

| Massage therapy | ||

| Classic western style Swedish massage (stroking the hands and feet or other parts of the body where there is muscle tightness and tension) | Aromatherapy (potential for skin irritation) | |

| Trigger-point therapy (repetitions of manual pressure and release to a source of pain in a muscle) | ||

| Myofascial technique (manual therapy applied to muscles and fascia) |

All CIH providers could use a topical analgesic with menthol and provide self-care recommendations to use between treatment visits (eg, breathing techniques, muscle stretches, or self-massage).

Coordination of Care. Requests for CIH provider assessment and treatment services could originate from a resident, their families, or LTC staff. Once a request was made, a LTC nurse would obtain an order from the resident's primary medical provider (medical doctor or nurse practitioner). To encourage a culture that respected CIH providers' abilities to apply their professional judgment within their scope of practice, standardized orders allowed for “any or all of the included CIH modalities” to assess and treat patients. Alternatively, primary medical providers could opt out of the standardized orders and request a specific CIH modality. Orders included an initial CIH assessment and up to 6 treatment visits and were renewed if residents (or proxy) and CIH providers felt they would provide benefit and no harm.

CIH providers were encouraged to attend weekly interdisciplinary meetings with LTC nurse managers and social workers. Discussions included appropriateness of CIH care for specific residents, residents' responses to CIH care, and steps for discontinuing CIH care as needed. Informal meetings between CIH providers and nurse managers also occurred routinely. Additionally, CIH providers met weekly among themselves and with the project director (KW) to discuss challenges and potential solutions to implementing the CIH model, general issues in geriatrics, and emerging relevant scientific literature.

Operational Elements. Operational elements included a project organizational structure and standardized protocols and materials required to implement the model of care. A core team led by the project director (KW) was responsible for all aspects of project preparation, implementation, and evaluation and included a research investigator (RE), project manager/CIH provider representative (CV), and 3 LTC managers. The core team reported to an advisory committee comprised of leadership from the Volunteers of America and NWHSU. The core team designed protocols for key operational procedures including informed consent, doctor's orders, record keeping and storage, and secure record transfer. Implementation-related forms included consent documents (patient and proxy), checklists for medical record review, treatment forms, and data collection instruments. Data collection methods were chosen based on data accessibility, ease of administration (for staff, residents, and CIH providers), and suitability for residents with cognitive impairment.

Printed educational materials for residents and staff members regarding CIH services were designed and included descriptions of potential benefits as well as risks. Finally, the LTC site was assessed and prepared to ensure that adequate space and equipment was available for providing CIH modalities.

Training

To meet compliance and safety standards, CIH clinicians were trained in fall prevention, infection control, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and patients' rights. Additional geriatric-specific education was provided in skin fragility, cognition and behavior changes, pain assessment, communication, risk minimization, and data collection. Training was provided by individuals with background and expertise in content areas and included the project director (licensed family physician, clinical research scientist), co-investigator (licensed chiropractor, clinical research scientist), LTC facility staff, and consulting CIH educators and clinicians with experience providing care to the elderly. Special attention was given to educating CIH providers in the LTC culture and how to participate on healthcare teams, defining staff roles and establishing effective communication. Additionally, CIH providers were trained to modify CIH treatment delivery to accommodate the special circumstances in LTC settings, including restricted or limited movement of residents, and providing care without use of specialized equipment (eg, chiropractic and massage therapy tables), among others. In total, CIH practitioners underwent approximately 120 hours of preparatory training over a 3-month period. In addition to training CIH providers, educational sessions were also provided to LTC staff regarding CIH treatment. These were provided at LTC staff meetings, along with demonstrations of specific CIH modalities.

Phase II: Implementation and Evaluation

Implementation and evaluation of the CIH model took place over a 16-month period. All residents were considered potentially eligible. Safety and potential benefit were the two guiding criteria for receiving CIH and were confirmed at two levels. First, the LTC facility required the resident's primary medical clinician to approve orders for a CIH assessment (and up to 6 CIH visits). The second confirmation occurred at the CIH assessment, at which time the CIH provider evaluated the resident for safety and appropriateness of care (as outlined in Table 1). If the CIH provider deemed a resident ineligible for the care he or she was providing, the provider could refer the patient to another CIH discipline if it was included in the original medical order.

Five providers delivered CIH services; 2 chiropractors, 2 acupuncturists, and 1 massage therapist. Each provider was available to provide care at the LTC 8 hours per week.

The specific treatment modalities offered by each provider type are summarized in Table 1. Chiropractic visits were scheduled for 30 minutes, and acupuncture and massage therapy visits were scheduled for 30 to 45 minutes.

Data Collection Methods

Our goal was to collect quantitative data on all residents enrolled in CIH. The CIH providers abstracted demographic and clinical characteristics from LTC facility resident charts onto standardized forms. Main complaint, pain, and QOL were collected verbally from the resident by the CIH provider prior to each treatment and recorded on standardized progress notes. Data recorded at the last CIH treatment visit was considered the final posttreatment data point. In cases in which more than one CIH provider delivered treatment, the final posttreatment data point was collected by the last CIH provider to deliver care.

Pain was measured using the Faces Pain Scale, which consists of 7 facial expressions representing increasing levels of pain (0=no pain, 6=most pain); the scale has demonstrated reliability and validity in older adults.21-23 QOL was measured using a vertical visual analogue scale (0=worst possible health, 100=best possible health) adapted from the EQ-5D questionnaire (EuroQol, Rotterdam, Netherlands).24 Adverse events were recorded at each treatment visit. Providers queried residents, proxies, and staff regarding expected and other side effects since the last treatment visit.

Interviews with LTC staff, residents and family members were conducted after treatment (by LB) to explore experiences with CIH care using a semi-structured schedule of questions. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. We aimed a priori to interview 20 to 25 residents and/or proxies, and 20 to 25 staff members.

Descriptive statistics were used for patient demographic and clinical characteristics, treatment visits, and adverse events. For the pain and QOL measures, a difference score was calculated by subtracting the first data point value (pretreatment), from the last data point value (posttreatment). Due to the exploratory nature of the pilot study, no statistical comparisons were planned or performed. The transcribed qualitative interviews were analyzed using a template style content analysis from an inductive perspective by 4 individuals (RE, LB, and 2 others who were independent of the project). Transcribed texts were first reviewed independently to gain an understanding of the data and establish preliminary codes; codes were then discussed to create a working codebook that was then used for all interviews. Upon coding completion, the results were reviewed and reconciled until consensus was reached; codes were collapsed into major themes, then counted and presented as frequencies.25,26

RESULTS

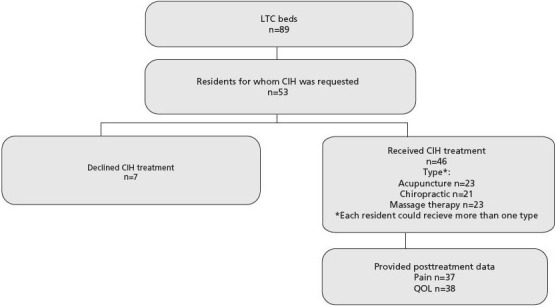

A total of 53 LTC residents and/or proxies requested care and gave consent to participate. Seven residents with proxy consent declined treatment at the initial assessment (1 resident was already receiving acupuncture from an outside provider and the proxy chose to continue with that care). Forty-six residents thus received CIH treatment in the pilot project (Figure 2). Three residents received only one treatment; 2 died, and for 1 the reason is unknown. Twenty-three residents received acupuncture, 21 received chiropractic, and 23 received massage therapy (note that patients could receive more than one type of care). A total of 859 CIH visits took place: 322 acupuncture, 295 chiropractic, and 242 massage therapy. The median number of visits per person was 13 (mean 18.8), with a range from 1 to 92.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants.

Abbreviations: CIH, complementary and integrative healthcare; LTC, long-term care; QOL, quality of life.

Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 2. Most participants were female, over the age of 80 years, at a risk for falls, and required assistance ambulating. On average, participants had mild cognitive impairment (mean mini mental status score=21.6) and were moderately depressed (mean geriatric depression score=10.7).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristicsa

| Characteristic | N=43-46b | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 39 | 85 |

| Age, y | ||

| 60-69 | 6 | 13 |

| 70-79 | 9 | 20 |

| 80-89 | 19 | 41 |

| 90+ | 12 | 26 |

| Medical History | ||

| Bleeding disorder | 10 | 22 |

| History of fragility fracture | 9 | 20 |

| MRSA/VRE/CDIFF infection | 4 | 9 |

| Position restriction | 5 | 11 |

| Cognitive Pattern | ||

| Oriented to self | 38 | 83 |

| Oriented to place | 28 | 61 |

| Oriented to time | 25 | 54 |

| Minor forgetfulness | 14 | 30 |

| Intermittent confusion | 13 | 28 |

| Totally disoriented | 0 | 0 |

| Safety and Vulnerability | ||

| Potential for falls | 28 | 61 |

| Fragile skin | 9 | 20 |

| Frequent falls | 3 | 7 |

| Skin easily bruises | 3 | 7 |

| Hits staff | 3 | 7 |

| Potential for elopement | 3 | 7 |

| Skin easily tears | 2 | 4 |

| Wanders | 1 | 2 |

| Hits other resident | 0 | 0 |

| Transfer Ability | ||

| 1 assist | 20 | 44 |

| Gait belt | 14 | 30 |

| Independent | 9 | 20 |

| 2 assist | 9 | 20 |

| SBA/CGA | 7 | 15 |

| Mechanical lift | 4 | 9 |

| EZ/Invacare stand up | 3 | 7 |

| Ambulation Ability | ||

| 1 assist | 15 | 33 |

| Walker | 13 | 28 |

| Wheelchair | 11 | 24 |

| Independent | 9 | 20 |

| Gait belt | 7 | 15 |

| SBA/CGA | 4 | 9 |

| 2 assist | 4 | 9 |

| Supervision | 2 | 4 |

| Cane | 0 | 0 |

| Mean (sd) | ||

| Geriatric Depressionc | 10.7 (17.8) | |

| Mental stated | 21.6 (12.4) |

Demographic and clinical characteristics were originally collected by long-term care staff members and then abstracted from resident charts onto standardized forms by the CIH providers.

Demographic and clinical data were obtained for those residents who received treatment (n=46). A total of 1-3 individuals were missing medical history, geriatric depression and mental state data.

Geriatric depression measured with the Geriatric Depression Scale, short form (score 0-15, with higher score suggesting depression).

Mental State measured with the Mini Mental State Examination (score 0-30, with higher score indicating better cognitive function).

Abbreviations: CDIFF, C difficile infection; CGA, contact-guard assistance; CIH, complementary and integrative healthcare; EZ/Invacare stand up, EZ lift/Invacare stand-up mechanical lifts for resident transfer; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SBA, stand-by assistance; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci.

By far, the most common primary reason for CIH care at the first visit was a musculoskeletal-related issue followed by a mental health issue (anxiety, agitation, depression), insomnia, general wellness, other pain, and other varied health issues including genitourinary, respiratory, and other. Of those who provided data at pre- and posttreatment time points, the mean difference in pain was –0.9 (n=37) and for QOL 3.9 (n=38) (Table 3).

Table 3.

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Difference Score | No. of Treatments | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

N | Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

N | Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

N | Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

|

| Pain | 3.0 | 3 | 3 | 2.1 | 2 | 3 | –0.9 | –1 | 3 | 18.4 | 13 | |

| (0-6) | 42 | (2.0) | (0 to 6) | 7 | (1.7) | (0 to 6) | 7 | (2.0) | (–6 to 3) | 7 | (20.3) | (2 to 92) |

| QOL | 58.8 | 60 | 3 | 63.6 | 70 | 3 | 3.9 | 3 | 3 | 19.5 | 13 | |

| (0-100) | 44 | (24.9) | (0 to 100) | 8 | (29.0) | (0 to 100) | 8 | (35.1) | (–81 to 100) | 8 | (21.2) | (2 to 92) |

Table reflects data for residents who contributed pre- and posttreatment data; number of treatments was from first to last data point. Data were collected verbally from the resident by the CIH provider prior to each treatment and recorded in standardized progress notes. Data recorded at the last CIH treatment visit were considered the final posttreatment data point.

Of the 46 residents who received at least 1 treatment, data were missing for the following reasons:

Pretreatment: visual and cognitive disabilities, n=2 for QOL, n=4 for pain.

Posttreatment: visual and cognitive disabilities, n=3 for QOL, n=4 for pain; 1 treatment provided so no posttreatment data collected, n=3 (2 died, 1 reason unknown).

Abbreviations: CIH, complementary and integrative healthcare; QOL, quality of life.

No serious (ie, life-threatening) adverse events related to treatment were documented. Mild, expected side effects did occur and were determined to be likely related to treatment. The most common was increased pain (63 reports) followed by sleep disturbances/behavior change (40 reports), muscle soreness (7 reports), fatigue (6 reports), and flushing (1 report) over the 859 visits. Seven individuals enrolled in CIH services died from preexisting health conditions or natural causes over the course of the project.

Twenty-five individuals representing the residents' experience (16 residents, 9 family members) participated in the qualitative interviews. Approximately half of these individuals (n=14) stated that they had no concerns regarding CIH treatment. As expressed by one resident, “I just wanted anything that's going to help me.” One-third (n=8) shared that they had concerns prior to care, mainly related to acupuncture and chiropractic due to unfamiliarity with those types of care. As one resident noted, “[My concerns] were more things about how does this work … I've never had this done.”

Most individuals (n=18) felt that CIH treatment positively affected residents' overall QOL. One resident said, “I think it's because we get such a degenerating feeling, we feel like we're getting old, and, and we feel like we're not going be around long … I'm feeling better.” Nearly a third of individuals (n=9) perceived CIH treatment as helpful, providing physical relief including diminished pain, muscle relaxation, enhanced joint mobility, and psychological or social benefits related to touch and personal attention. One resident said, “I can move my leg … before, I couldn't.” Another family member said, “I think that touch is a large part of health. Especially when people are really older and so any type of touch is, generally speaking, a positive thing.”

Nearly two-thirds (n=15) expressed a desire for the services to be available in the future. Eight individuals did not want continued CIH services due to either lack of perceived benefit, limitations of advancing age, or potential expense of future care. The majority of the residents or their family members interviewed (n=20) felt the CIH services were worthwhile. The most common reasons given were perceived benefits, including relief of discomfort, enhanced function, and better psychological and social wellbeing. One resident described the value of CIH as follows: “Oh, just wellness, being able to smile again, feel relieved … little bit livelier and relax[ed].”

A total of 21 staff members participated in qualitative interviews. When asked about the biggest challenges of implementing CIH, they most commonly cited the logistics of coordinating care (n=19). Staff members' and residents' own lack of knowledge of CIH was also mentioned as a barrier (n=15):

All staff members interviewed expressed the view that CIH was beneficial to their workplace due to their perception that CIH improved residents' overall health (n=11), psychological and social wellbeing (n=10), and pain management (n=9). Some staff members felt “an indirect effect” of residents' feeling better, making their work easier. A total of 11 individuals reported CIH as having no impact on their own personal work at the LTC facility; 9 cited a positive impact. Two individuals cited a negative impact related to disruptions to work flow. All staff members expressed they felt CIH was worthwhile for their LTC residents, citing similar benefits as conveyed by the residents and their family members. One person noted, “I see some of these people and they're just getting pumped full of medications, but yet they still stay the same, and then I see people who are going to the chiropractor, or going to massage therapy, acupuncture, and they're improving.” As stated by another staff member, “The more holistic approach gives them hope.”

DISCUSSION

Many older individuals are unable to maintain living independently and need some form of LTC as they age.1 Those resorting to LTC facilities often incur substantial physical, psychological, social, and financial impacts,12,13 and healthcare models that can minimize these burdens are critically needed. This pilot project is among the first to report on the delivery of CIH for 46 residents in a LTC facility in the United States. The most common reason for CIH was musculoskeletal pain, and the median number of CIH treatments provided was 13, with a range of 1 to 92. Residents who were able to provide self-report data demonstrated on average a 15% decline in pain and a 4% improvement in quality of life. No serious adverse events related to CIH treatment were documented; the most common mild and expected side effect was increased pain (63 reports over 859 treatments). Qualitative interviews found that most residents, family members, and LTC staff considered the CIH care to be worthwhile.

The preparatory phase yielded a patient-centered model of CIH services that defined scope of care, coordination of care, and operational elements guided by principles of collaborative integration, evidence-informed practice, and sustainability. The implementation and evaluation phase revealed that implementation of the model was feasible on several levels. A highlight of the project was the collaborative working relationships that developed between administrators, LTC staff, and CIH providers. Individuals working in LTC and CIH have unique cultures that were at first foreign to the other. The project director (KW), a family medical physician, had experience with both and played a unique role in bridging professional differences and facilitating communication and collaboration, a guiding foundational principle for the CIH model. Further, having a comprehensive understanding of medical care and an appreciation for the role of research evidence were key in gaining the trust of LTC nurses and residents' primary care physicians. This draws attention to the necessity of ensuring CIH implementation is led by qualified individuals who are able to foster the necessary buy-in and team-building required for true integration.

Descriptive data from the project suggest that CIH can be delivered safely in LTC settings using a well-delineated model accompanied by robust training. The reduction in patient self-reported pain (–0.9, or 15%) and improvement in QOL (3.9, or 3.9%) cannot be directly attributed to the therapies due to the nature of the pilot study and limitations of design; a randomized controlled trial is necessary to determine the effectiveness of CIH for LTC residents. Further, the observed improvements in pain and QOL were not large. However, an important goal in LTC facilities is preventing decline in residents' health. Consequently, even small improvements in pain and QOL, if reproduced in an adequately powered randomized controlled trial, may still be considered important due to the challenges of pain management for older people in both LTC and community settings.22,27,28

More than 800 CIH treatments were safely provided over the course of this project. The adverse events that were reported were considered mild and expected, transient in nature, and not requiring medical care. Further, no serious (ie, life-threatening) adverse events related to CIH treatment were documented, though determining temporal relationships between treatment and adverse events in individuals with extensive comorbidities is a difficult and imperfect process.29 Consequently, these data should be interpreted with a degree of caution as they may represent over- or underestimates of true adverse events.

Qualitative interviews of residents, their family members, and staff members revealed support for including CIH in the LTC facility. Notable, however, was that nearly one-third of residents and/or their family members interviewed did not want continued CIH services because of lack of perceived benefit, limitations of advancing age, and potential expense of future care. These results raise important issues surrounding the outcomes that are valued and who will pay for the care. Indeed, a cost analysis is an essential part of determining the sustainability of new healthcare models in whatever setting they are implemented. Such an analysis was beyond the scope of this pilot project. Future studies seeking to evaluate the implementation of CIH into LTC must consider all costs associated with CIH delivery, reimbursement possibilities, and the perceived value of CIH by patients, families, LTC facilities, payers, and policy makers. While qualitative data generated from this project suggest that many residents, family members, and staff members felt CIH services were worthwhile, the issues of who is willing to pay for them, how much they will pay, and for what indications (eg, pain management, overall wellbeing) must be raised and resolved for successful implementation and sustainability.

While the preparatory phase afforded necessary relationship building and development of protocols and procedures that facilitated implementation, challenges were encountered that might threaten the reproducibility and sustainability of such a model. First, overuse of CIH services was a problem in some cases with a few patients becoming high utilizers despite the protocol for renewing orders every 6 visits. Potential solutions to avoid overuse include training CIH providers to recognize and better deal with psychosocial issues associated with care seeking behavior; alerting LTC staff of their own potential in contributing to a culture of overuse by too heavily relying on CIH providers to provide relief in caring for the most demanding patients; and setting better defined indications for continuing care in attempts to prevent or slow decline in QOL. Second, physical barriers to implement CIH services frequently arose. All of the CIH provider types routinely use specialized equipment or patient positioning to deliver customary care; this was difficult to accomplish within the LTC setting due to lack of equipment and resident positioning restrictions. Further, most of the participating residents were at risk for falls and required assistance ambulating and transferring. CIH providers spent considerable time coordinating the necessary transfers, which cut into CIH treatment time. Also, while modifications to care were made in many instances, they also might have limited the full potential of CIH's treatment effect. Future models should give greater consideration to providing sufficient space and equipment, as well as certified staff assistance with physical transfers of residents when necessary. Finally, qualitative interviews revealed that one of the biggest challenges from the LTC staff members' perspective included logistics of coordinating care (eg, processing doctors' orders). Those planning to implement CIH in LTC should pay very close attention to refining the coordination of care to make it as seamless as possible for LTC staff. While systematic protocols can be helpful in maintaining compliance and safety standards, it is essential that they employ only those steps that are absolutely essential.

Those embarking on implementing CIH models into LTC should give careful consideration to the training needs of CIH providers and LTC staff to ensure resident safety and facility compliance standards are met. During the preparatory phase of this project, it became apparent that LTC staff knew very little about CIH. Further, CIH providers had varied clinical experience and backgrounds with only basic previous training in care of older adults. Overall, they lacked training in geriatric-specific issues most relevant to LTC (eg, skin fragility, cognition and behavior changes, fall prevention). The identification of these skill and knowledge gaps highlighted the utility of the assessment aspect of the preparatory phase to identify and address staff and provider training needs so that care could be delivered safely and effectively.

Limitations

The model of CIH developed in this project was oriented to the needs and values of specific stakeholders (LTC residents, facility staff, and CIH providers) at one LTC facility in the midwestern United States and might not be ideal or generalizable for other settings. Indeed, this project benefited from institutional funding and support, and other facilities may not have sufficient resources to implement the model as described. However, the steps described during the preparatory phase to develop the model and train participating providers can be used as a guide for others seeking to integrate CIH in LTC and similar settings.

This pilot project focused on the integration of 3 CIH professional care provider types who could provide a range of CIH modalities (Table 1). While these are among the most common of the CIH professions in the United States, there are others from which LTC residents might also benefit (eg, osteopathy, naturopathy). Further, there are also other CIH modalities to consider that do not require licensed professionals for delivery (eg, mindfulness meditation, modified yoga, tai chi) and that might prove more economically feasible to implement.

The outcomes data should be interpreted cautiously for several reasons. First, there are the inherent limitations associated with a nonrandomized study design with no comparator group leading to the inability to attribute changes solely to the intervention. Additionally, each CIH discipline included a variety of modalities including those that might be considered conventional (eg, menthol, self-care). This limits the ability to discern which of the specific CIH modalities might contribute to improved outcomes. The goal of this project, however, was not to determine CIH efficacy; rather, it aimed to develop a CIH intervention model that was pragmatic in nature so that it could be applied in LTC settings.

Collecting self-reported patient-centered data in healthcare settings with minimal disruptions to care is always a challenge. It is especially difficult to choose and implement reliable and valid measures for use in LTC settings where barriers are common.30 Indeed, some of the participating residents had difficulty deciphering our pain and QOL scales, and we encountered several residents for whom data collection was not possible at all, resulting in considerable missing data (eg, 36-37 of 43 participants provided posttreatment data). Also, the majority of residents could not fill out self-report questionnaires on their own due to physical or cognitive disabilities, and because of resource constraints, CIH providers were relied upon for data collection. While careful attention was paid to training CIH providers in nonbiased data collection, the potential for risk of bias is elevated, and results should be interpreted with caution. Future studies seeking to assess the effectiveness of CIH in LTC will need to pay careful attention to providing sufficient resources (eg, independent staff) for collecting complete and unbiased data and choosing the most appropriate outcome measures for their populations. Also, more objective measures such as healthcare utilization and medication use should be considered. Finally, measures that more fully query resident, family, and LTC staff wellbeing would be useful. While this project addressed some important features of wellbeing (eg, pain and QOL of the resident), the qualitative data suggest that CIH more broadly affects important psychological and social wellbeing domains important to all parties involved in LTC.31

CONCLUSION

The provision of care for aging individuals is a growing concern worldwide, and the search for safe and effective healthcare models is critical. This pilot project represents a first step for investigating the role of CIH for LTC residents. We found that one patient-centered model that focused on principles of collaborative integration, evidence-informed practice, and sustainability was feasible on several levels. Further, both the quantitative and qualitative data suggest that CIH can be delivered safely with proper training and preparation and has the potential through a holistic and gentle approach to provide LTC residents relief and enhanced wellbeing. Some aspects of model delivery and data collection posed challenges, however, and resulted in limitations in assessing the full value of CIH; these should be carefully considered in future endeavors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts and enthusiasm of all participating staff, providers and residents.

Financial support for the project was provided by the Volunteers of America and Northwestern Health Sciences University's Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies. Training of CIH providers in evidence-informed practice was provided through an ongoing education project funded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, R25AT003582). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCCAM, Volunteers of America, or Northwestern Health Sciences University.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and disclosed receipt of a grant from Volunteers of America. See the Acknowledgments section of the article for more information.

Contributor Information

Roni Evans, Integrative Health & Wellbeing Program, Center for Spirituality & Healing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

Corrie Vihstadt, Integrative Health & Wellbeing Program, Center for Spirituality & Healing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

Kristine Westrom, Integrative Health & Wellbeing Program, Center for Spirituality & Healing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

Lori Baldwin, Integrative Health & Wellbeing Program, Center for Spirituality & Healing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute on Aging. Why population aging matters: a global perspective. http://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/why-population-aging-matters-global-perspective AccessedDecember17, 2015.

- 2.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population ageing: 1950-2050. http://www.un.org/esa/population//publications/worldageing19502050/pdf/preface_web.pdf AccessedDecember17, 2014.

- 3.National Institute on Aging. Global health and aging. http://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global-health-and-aging/preface AccessedDecember17, 2014.

- 4.Administration for Community Living. A profile of older Americans. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/index.aspx AccessedDecember17, 2014.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & you: 2015. http://www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/10050.pdf AccessedDecember17, 2014. [PubMed]

- 6.American Health Care Association. LTC stats: nursing facility patient characteristics report. http://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/oscar_data/NursingFacilityPatientCharacteristics/LTC%20STATS_HSNF_PATIENT_2013Q3_FINAL.pdf AccessedDecember17, 2014.

- 7.Gallagher PF, Barry PJ, Ryan C, Hartigan I, O'Mahony D. Inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of elderly patients as determined by Beers' Criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruckenthal P. Integrating nonpharmacologic and alternative strategies into a comprehensive management approach for older adults with pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11(2 Suppl): S23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin CM. Complementary and alternative medicine practices to alleviate pain in the elderly. Consult Pharm. 2010;25(5):284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin AB, Hartman M, Whittle L, Catlin A, the National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National health spending in 2012: rate of health spending growth remained low for the fourth consecutive year. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genworth Financial Inc. Genworth 2014 cost of care survey: home care providers, adult day health care facilities, assisted living facilities and nursing homes. Richmond, VA: Genworth Financial Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health Policy Forum. National spending for long-term services and supports (LTSS), 2012. http://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LTSS_03-27-14.pdf AccessedDecember17, 2014.

- 13.Ragsdale V, McDougall GJ., Jr The changing face of long-term care: looking at the past decade. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2008;29(9):992–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323(7311):486–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. A prospective survey of adverse events and treatment reactions following 34,000 consultations with professional acupuncturists. Acupunct Med. 2001;19(2):93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carnes D, Mars TS, Mullinger B, Froud R, Underwood M. Adverse events and manual therapy: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008; (12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer M, Rayner JA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in residential aged care. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(11):989–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boon H, Verhoef M, O'Hara D, Findlay B. From parallel practice to integrative health care: a conceptual framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor B, Delagran L, Baldwin L, et al. Advancing integration through evidence informed practice: Northwestern Health Sciences University's integrated educational model. Explore (NY). 2011Nov-Dec; 7(6):396–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, Addicoat L, Ziegler JB. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41(2):139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009August; 57(8):1331–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herr KA, Mobily PR, Kohout FJ, Wagenaar D. Evaluation of the Faces Pain Scale for use with the elderly. Clin J Pain. 1998;14(1):29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Pol. 1990;16(3):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer M. Classical content analysis: a review. : Bauer M, Gaskell G, Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: a practical handbook for social research. London, UK: Sage Publications, Inc; 2000:131–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell J, Plano-Clark V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrell BA, Ferrell BR, Rivera L. Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(8):591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teno JM, Weitzen S, Wetle T, Mor V. Persistent pain in nursing home residents. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maiers M, Evans R, Hartvigsen J, Schulz C, Bronfort G. Adverse events among seniors receiving spinal manipulation and exercise in a randomized clinical trial. Man Ther. 2014October14 pii: S1356–689X(14) 00185–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herr KA, Garand L. Assessment and measurement of pain in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17(3):457–78, vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreitzer MJ, Koithan M. Integrative nursing: New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]