Abstract

Background

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have been shown to traffic to and incorporate into ischemic tissues, where they participate in new blood vessel formation, a process termed vasculogenesis. Previous investigation has demonstrated that EPCs appear to mobilize from bone marrow to the peripheral circulation after exercise. In this study, we investigate potential etiologic factors driving this mobilization and investigate whether the mobilized EPCs are the same as those present at baseline.

Methods

Healthy volunteers (n=5) performed a monitored 30-minute run to maintain a heart rate > 140 bpm. Venous blood samples were collected before, 10 minutes after, and 24 hours after exercise. EPCs were isolated and evaluated.

Results

Plasma levels of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1α) significantly increased nearly two-fold immediately after exercise, with nearly a four-fold increase in circulating EPCs 24 hours later. The EPCs isolated following exercise demonstrated increased colony formation, proliferation, differentiation and secretion of angiogenic cytokines. Post-exercise EPCs also exhibited a more robust response to hypoxic stimulation.

Conclusions

Exercise appears to mobilize EPCs and augment their function via SDF-1α dependent signaling. The population of EPCs mobilized following exercise is primed for vasculogenesis with increased capacity for proliferation, differentiation, secretion of cytokines, and responsiveness to hypoxia. Given the evidence demonstrating positive regenerative effects of exercise, this may be one possible mechanism for its benefits.

Keywords: Endothelial progenitor cell, mobilization, SDF-1, vasculogenesis, exercise

INTRODUCTION

Since their first description in 1997 [1], evidence has accumulated to suggest that circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) play an important role in the maintenance of vasculature [2] and recovery of ischemic tissue [3]. In murine models, EPCs have been shown to traffic to ischemic tissues [4] and participate in new blood vessel formation, a process termed vasculogenesis [5]. However, there is controversy in the literature regarding the mechanism by which EPCs elicit their angiogenic effects. EPCs may either differentiate into mature endothelium and incorporate directly into neovessels [6], or as more recent studies suggest, they stimulate neovascularization via paracrine mechanisms [7, 8].

Central to their role in ischemic neovascularization is the ability of EPCs to respond to ischemic events, which is believed to occur through the activity of the chemokine stromal cell–derived factor-1 alpha (SDF-1α). SDF-1α mediates the mobilization and trafficking of stem or progenitor cells expressing the receptor CXCR4 [9–12]. We have previously demonstrated that induction of SDF-1α is dependent on stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), a transcription factor that serves as a central regulator in the tissue response to hypoxia [4]. SDF-1α concentrations are therefore greatest in the most hypoxic regions of ischemic tissue or cutaneous wounds, promoting the incorporation of EPCs into healing tissue [3, 5, 13–15]. However, the characteristics of newly mobilized EPCs and the mechanisms that promote their release from bone marrow in response to hypoxia are poorly understood.

Physical exercise has been shown to increase the prevalence of monocytes and pro-angiogenic circulating cells [16, 17]. However, a link between physical activity and changes in EPC functionality after mobilization has never been investigated. In this study, we aimed to examine the effects of exercise on EPC mobilization and function at cellular and molecular level. A single bout of exercise was used to investigate the prevalence and function of circulating EPCs in young healthy subjects. Characteristics of EPCs harvested before, immediately after exercise and 1-day later were assessed by prolonged culture in hypoxia. Utilizing this experimental approach, we measured EPC functionality by determining colony-forming capacity and recording changes in angiogenic cytokine profiles. We observed that exercise induced changes in the phenotype and prevalence of circulating cells. Further, these changes appear to be driven by differences in HIF-1α stabilization after exercise.

METHODS

Exercise Protocol

Non-smokers without any significant medical history were recruited for this study (n=5). The average age was 29.8 years (26–36) and the average BMI was 24.48 (22.7–26.5). Test subjects demographic details are summarized in Table 1. All volunteers were screened by interview and those with cardiovascular comorbidities or undergoing pharmacologic treatment for cardiovascular disease were excluded from the study. A cohort with comparable fitness levels was selected and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Subjects were instructed to refrain from excessive physical activity for a 72-hour period prior to the study. Excessive physical activity was defined as any exercise or other strenuous actions that would induce sweating. Volunteers then performed a single monitored 30-minute treadmill run to maintain a heart rate above 140 bpm. Blood samples (twenty-thirty mL of venous blood) were collected via antecubital venipuncture before, 10 minutes after, and 24 hours after exercise. All blood samples were processed for complete blood count, circulating progenitor cell quantification, EPC culture, and plasma collection. Exercise and blood collection protocols were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Subject demographics.

| Patient | Age (years) | Weight (kg) | Height (m) | BMI (kg/m2) | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 | 70 | 1.67 | 25.1 | M |

| 2 | 28 | 65 | 1.65 | 23.9 | M |

| 3 | 31 | 80 | 1.82 | 24.2 | M |

| 4 | 36 | 68 | 1.73 | 22.7 | M |

| 5 | 28 | 83 | 1.77 | 26.5 | M |

EPC Culture

EPC colonies were cultured as previously described [18]. Briefly, mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from peripheral blood samples using Ficoll-Paque PLUS density gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare, Newark, NJ). Isolated cells were then seeded in Medium 199 (Gibco Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum onto fibronectin-coated six-well plates (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 5 × 106 cells/well. After two days in culture, non-adherent cells were transferred onto 24-well fibronectin-coated plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well. Seeded cells were then incubated in either normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions at 37°C and 5% CO2 for an additional five days after which EPC colony counts were performed. Colonies were counted manually in a minimum of four wells by blinded observers.

EPC Quantification by Flow Cytometry

Primary mononuclear cells and cultured EPCs were analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described [3, 4]. Viable cell populations were analyzed for CD11b-PE, CD34-APC, VEGFR2-FITC (BD Biosciences), and AC133-PE-Cy7 (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). VEGFR2+/CD11b−/CD34+/AC133+ cells were defined as EPCs. Isotype-identical antibodies (BD Biosciences) served as controls in each experiment. Samples were run on a LSRI analyzer (BD Biosciences) with a minimum of 200,000 events for mononuclear cells and 50,000 events for cultured EPCs. Data were analyzed using FLOWJO software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Thymidine Incorporation Assay

1 × 103 cultured EPCs in 100 µl of media were seeded per well in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37° C overnight to allow attachment. 5 µCi/ml of [3H] thymidine was added to each well and incubated for 6 hours. After collection of cell lysate, counts were determined by liquid scintillation.

Cytokine Quantification

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin (EPO), and SDF-1α levels were determined with corresponding Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were performed on donor plasma and conditioned media collected from EPC cultures.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After multiple wash steps with PBS and blocking of non-specific binding with Powerblock (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA), antigen detection was performed with mouse anti-human CD31-PE and VEGFR2-FITC conjugated antibodies (BD Biosciences). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Standard immunofluorescence imaging was performed on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Cark Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY). Images were prepared for publication using Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Quantitative Real-time Reverse Transcription–PCR

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription–PCR was performed with the Roche Light Cycler Sequence Detection System (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers for HIF-1α were 5-TTACCCACCGCTGAAACG-3 and 5-TGCTTCCATCGGAAGGAC-3. Primers for the control housekeeping gene GAPDH were 5-AACATCATCCCTGCCTCTAC-3 and 5-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAAT-3. Transcription levels for HIF-1α were calculated as relative units to GAPDH. All primers were synthesized upon request by the Peptide and Nucleic Acid Core Facility at Stanford University.

HIF-1α Western Blot

20 µg of total protein extracted with RIPA buffer (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were separated on 4–12% SDS-PAGE gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Protein detection was performed with rabbit anti-human primary antibodies against HIF-1α (Novus, Littleton, CO) and β-actin (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA). Corresponding goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase–linked antibodies were used as the secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were developed with ECL reagent (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and exposed on Kodak Biomax-MS film.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise stated, all statistics are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Where applicable, univariate analyses were completed using an unpaired Student’s t-test with Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Multivariate analyses were accomplished using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test by GraphPad Prism version 4.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

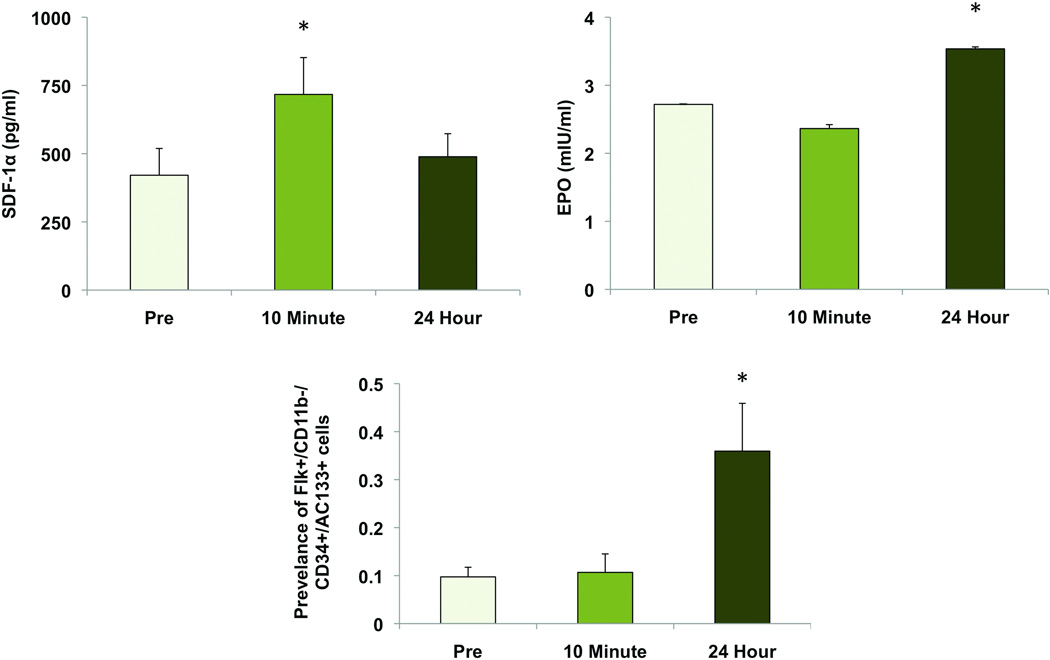

Exercise Increases Plasma SDF-1α and EPO Levels

A moderate exercise session of 30 minutes was chosen to evaluate the effects of an efficient and healthy level of activity that could be performed on a daily basis [19]. Plasma samples collected at the three time points were assayed for the presence of the HIF-1α–inducible cytokines SDF-1α and EPO. SDF-1α levels were present in the pre-exercise circulation (421 ± 98.2 pg/ml) and significantly increased 1.7-fold in the immediate post-exercise period (717 ± 135 pg/ml, p<0.01). Plasma SDF-1α concentrations returned to baseline levels after 24 hours (489 ± 84.4 pg/ml) (Figure 1A). EPO concentrations did not elevate significantly until 24 hours after exercise, increasing from 2.72 ± 0.002 mIU/ml to 3.54 ± 0.029 mIU/ml (p<0.01) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Plasma cytokine levels before and after a 30-minute exercise session. (A) SDF-1α levels are significantly increased immediately after exercise (p<0.01) and return to baseline levels after 24 hours. (B) EPO remains at pre-exercise levels immediately after exercise and increases after 24 hours (p<0.05). (C) Prevalence of circulating EPCs before and after a 30-minute exercise session. EPCs were defined as VEGFR2+/CD11b−/CD34+/AC133+ and enumerated by flow cytometry. Circulating levels were unchanged immediately after exercise and increased 3.6-fold when assessed after 24 hours (p<0.05). *, p<0.05 vs pre-exercise.

Exercise Increases Circulating Progenitor Cell Populations

Although a universally accepted cell-surface marker profile has yet to be established, previous studies have suggested that EPCs can be defined as VEGR2+/CD34+/AC133+ [20, 21]. We have added the negative selection of CD11b to exclude monocytes which have been demonstrated to be a non-vasculogenic population present under earlier EPC definitions [8]. Using this panel of cell-surface markers, basal levels of EPCs were found to exist at a prevalence of 0.10 ± 0.02% of total circulating mononuclear cells. There was no significant change in EPC prevalence immediately after exercise (0.11 ± 0.04%); however, circulating EPC counts increased 3.6-fold 24 hours after exercise (0.36 ± 0.09%, p<0.05) (Figure 1 C).

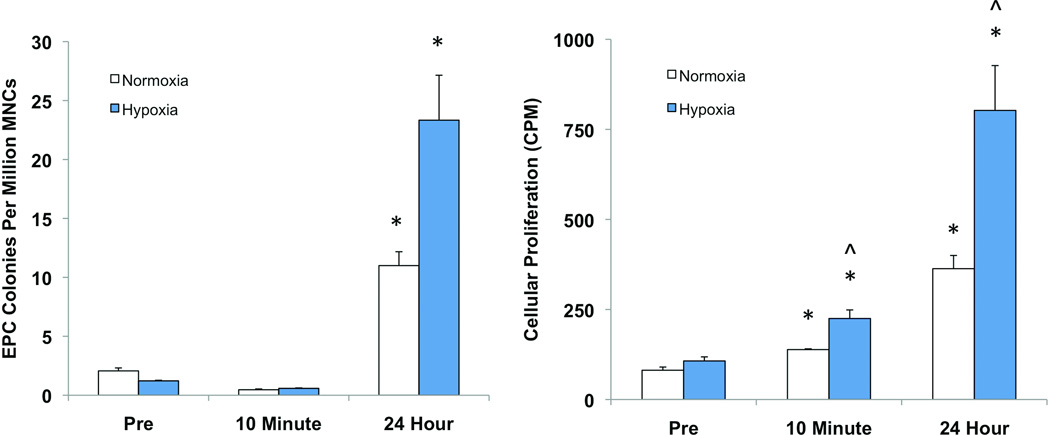

Exercise Increases EPC Colony Formation and Proliferation

EPC colonies were quantified by counting colony-forming units after plated mononuclear cells were expanded in culture for seven days [18]. EPC colony counts were 2.1 ± 0.25 colonies/million MNCs in pre-exercise samples. Colony counts increased 5.3-fold (11 ± 1.2 colonies/million MNCs) when samples were collected 24 hours after exercise were compared to pre-exercise controls. No difference was observed in cells collected immediately post-exercise (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

EPC colony forming ability and proliferation in vitro in response to exercise and hypoxic stimulation. (A) EPCs collected 24 hours after exercise exhibited significantly greater colony formation in both normoxic (21% O2) and hypoxic (1% O2) culture conditions (p<0.05). Exposure to hypoxia elicited a 2.1-fold increase in colony formation in EPCs collected 24 hours after exercise (p<0.05). Cells from other time points did not demonstrate a significant response. (B) Cellular proliferation assessed by tritiated thymidine incorporation assay closely parallels colony forming data. Both post-exercise and 24-hour EPCs demonstrated increased proliferation under normoxic and hypoxic conditions compared to the pre-exercise cells (p<0.01). Post-exercise EPCs demonstrated a 1.6-fold increase in proliferation in response to hypoxia while EPCs collected 24 hours after exercise had a 2.2-fold increase (p<0.05). EPCs collected prior to exercise did not exhibit any increased response to hypoxia. *, p<0.05 vs pre-exercise. ^, p<0.05 vs normoxia.

Cellular proliferation of EPCs in culture was quantified by a [3H] thymidine incorporation assay. Cells isolated immediately after exercise demonstrated a 1.7-fold increase in proliferation compared to pre-exercise samples, while a 4.5-fold increase was observed in EPCs isolated 24 hours after exercise under normoxic conditions (p<0.01) (Figure 2B).

We repeated these assays under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) to assess EPC function in a setting similar to tissue ischemia. Colony counts increased over 19-fold in samples collected 24 hours after exercise (23 ± 3.8 colonies/million MNCs) compared to pre-exercise controls (1.2 ± 0.05 colonies/million MNC, p<0.05) when grown in hypoxia. Again, no difference in colony forming capacity was found in cells collected immediately post-exercise. We also compared colony formation in hypoxia versus normoxia in cells from the three time points. Only EPCs isolated 24 hours after exercise demonstrated significantly increased colony formation in response to hypoxia (Figure 2A).

In the setting of hypoxia, EPCs isolated immediately after exercise demonstrated a 2.4-fold increase in proliferation compared to baseline EPCs (p<0.01). An even greater 7.5-fold increase was observed in the EPCs collected 24 hours following exercise (p<0.01). Both immediate post-exercise and 24-hour post-exercise EPC cultures demonstrated significantly increased proliferation in hypoxia versus normoxia, more so in the latter group (1.6 vs. 2.2-fold increase). Pre-exercise EPCs did not demonstrate increased proliferation in hypoxia (Figure 2B).

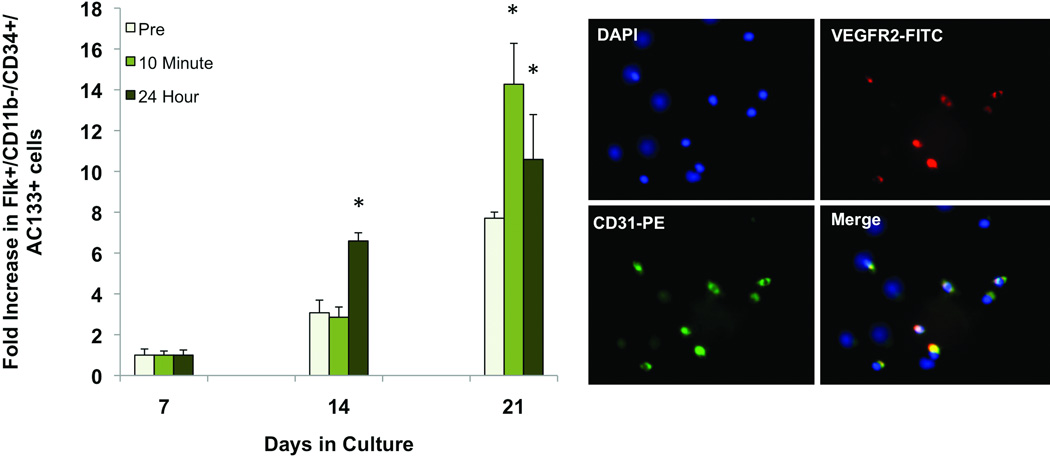

Exercise Augments EPC Differentiation

Differentiation of EPCs into cells with a mature endothelial-like phenotype was evaluated by performing flow cytometry to assess for acquisition of the endothelial-specific markers VEGFR2 and CD31 on cells after 7, 14, and 21 days in culture. VEGFR2+/CD31+ cells became more prevalent after 14 days in all samples, however increased significantly more in samples collected 24 hours after exercise. After 21 days, all cells again displayed increased acquisition of the endothelial cell markers. Both immediate post-exercise and 24-hour samples displayed significantly greater differentiation than the pre-exercise cells, however there was no statistical difference between the two conditions (Figure 3A). The presence of VEGFR2+/ CD31+ cells in culture was verified by immunofluorescence (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Endothelial differentiation of EPCs in culture. EPCs were grown in normoxia for 21 days. (A) Flow cytometry was used to assess cells for the endothelial specific markers VEGFR2 and CD31. Number of double positive cells at days 14 and 21 relative to day 7 are shown. VEGFR2+/CD31+ cells increased in pre-exercise, post-exercise, and 24 hour EPCs at days 14 and 21. At day 14, EPCs isolated one day after exercise had a significantly greater number of differentiated cells than the other two time points (p<0.05). At day 21, both post-exercise and day one EPCs displayed significantly greater differentiation than the pre-exercise EPCs (p<0.05). (B) Representative picture of EPCs labeled by immunofluorescence for VEGFR2 (green) and CD31 (red). *, p<0.05 vs pre-exercise.

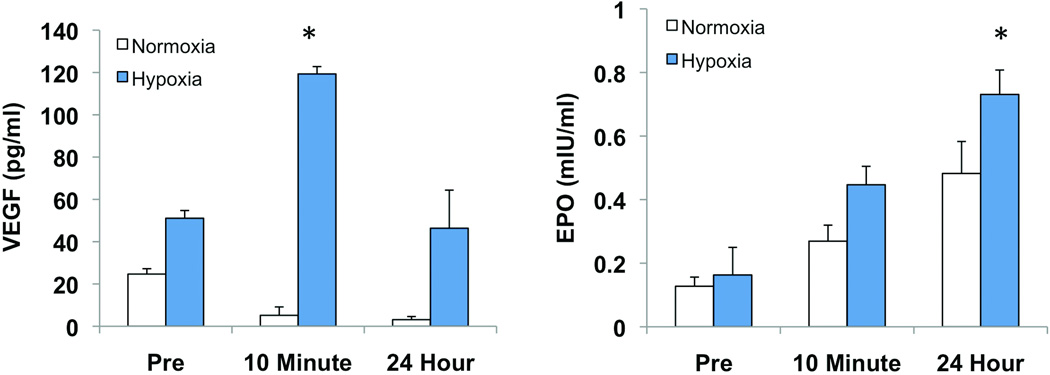

Exercise Increases EPC Paracrine Activity

Evidence is accumulating that EPCs may at least in part contribute to neovascularization via paracrine mechanisms. Accordingly, we assessed the secretory activity of EPCs by measuring cytokine levels in conditioned media from cultures grown in normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Under normoxic conditions, there were no significant differences in VEGF production from EPCs collected at the three different time points. Within cultures exposed to hypoxia, samples collected immediately after exercise produced more than twice the amount of VEGF as the pre-exercise samples (119 ± 3.4 vs 51 ± 3.6 pg/ml, p<0.05). Secreted VEGF levels from cultured EPCs harvested one day after exercise were statistically equivalent to the pre-exercise levels (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Cytokine activity of cultured EPCs. Conditioned media from EPC cultures was collected and assayed for the presence of VEGF and EPO. (A) Under normoxic conditions, EPCs collected post-exercise and 24 hours after exercise demonstrated decreased secretion of VEGF, however the difference was not significant. In hypoxic culture conditions, the immediate post-exercise cultures secreted significantly increased amounts of VEGF (p<0.05). (B) There was a trend for increased secretion of EPO in post-exercise EPCs and 24 hour EPCs under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. However, only samples collected 24 hours after exercise and cultured in hypoxia demonstrated an increase over pre-exercise levels that reached statistical significance. *, p<0.05 vs pre-exercise.

There was a trend for increased secretion of EPO from cells isolated immediately and 24 hours after exercise when cultured in normoxia; however, this trend did not reach significance. With hypoxic stimulation, cells collected one day after exercise demonstrated a 4.5-fold increase in secreted EPO compared to pre-exercise levels (Figure 4B).

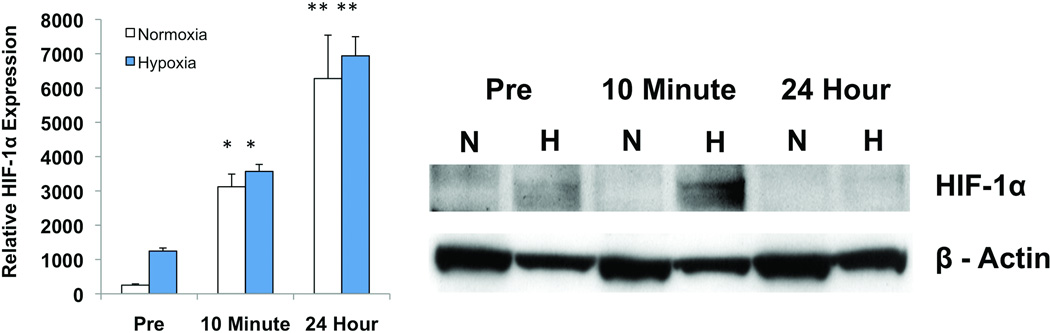

Exercise Increases HIF-1α Expression and Stabilization

HIF-1α expression by EPCs in culture was measured using quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR. Under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions, total RNA isolated from cultured EPCs demonstrated increased transcription of HIF-1 immediately after exercise when compared to pre-exercise levels (normoxia: 3120 ± 371 vs 252.7 ± 36.2; hypoxia: 3568 ± 203 vs 1246 ± 87.6, P<0.01). EPCs collected one day after exercise exhibited even greater expression of HIF-1 than those harvested immediately after exercise (normoxia: 6276 ± 1266; hypoxia: 6940 ± 557, p<0.05) (Figure 5A). As HIF-1α also undergoes post-translational regulation via degradation/stabilization, these data were confirmed at the protein level using standard Western blot technique. HIF-1α protein levels were increased under hypoxic stress in cells that were collected post-exercise (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Cumulative evidence demonstrates that HIF-1α is implicated in the enhanced properties of EPCs after a single session of exercise. (A) HIF-1α expression is increased in cultured EPCs collected immediately after exercise (p<0.01). EPCs isolated 24 hours after exercise exhibited even greater expression (p<0.05). (B) Induction of stabilized HIF-1α by exercise visualized on HIF-1α Western immunoblots. *, p<0.01 vs pre-exercise. **, p<0.05 vs 10 min post exercise.

DISCUSSION

Higher levels of circulating EPCs have been shown to be associated with healthy vascular function and regeneration [22, 23]. Conversely, disease states such as diabetes mellitus [24, 25], hypercholesterolemia [26], and coronary artery disease [27], where vascular function is impaired, are correlated with diminished EPC prevalence and function [28, 29]. Previous studies have established the link between exercise and improved outcomes for ischemic events [30, 31]. Recently, a partial explanation for the benefits of physical exercise has been proposed: non-pharmacological induction of EPC mobilization [32]. Several studies have observed that exercise can increase circulating progenitor cells in healthy individuals [8, 32] as well as those with coronary artery disease [33, 34]. Little is known, however, regarding the putative mechanism by which they are mobilized or whether these cells are functionally different as a result of exercise. In this study, we investigated the biological function of newly mobilized EPCs and potential mechanisms that promote their mobilization from the bone marrow niche.

We first examined the temporal relationship between systemic cytokine signaling, EPC mobilization, and EPC activity after a brief session of aerobic exercise. A 30-minute period of exertion was shown to be sufficient to elicit a transient upregulation of plasma SDF-1α immediately following exertion followed by a series of downstream effects on EPCs and their biological function. Although this study did not specifically investigate the origin of this increased plasma SDF1-α, the ischemic skeletal muscle environment induced by exercise may serve as a possible source of the chemokine [35]. In fact, recent work has shown that HIF-1α expression and stabilization are increased in skeletal muscle after exercise [36–38] and that muscle satellite cells and fibroblasts are capable of secreting SDF-1α to help recruit CD34+ progenitor cells to ischemic tissue [35, 39]. Accordingly, the circulating population of EPCs was observed to increase significantly one day after exercise, suggesting an SDF-1α mediated mobilization from the bone marrow niche.

We further analyzed the effects of exercise on the functional capacity of EPCs, finding that both cellular proliferation and colony forming capacity, important properties of any progenitor cell, were enhanced by aerobic activity. Previous work investigating the effects of EPO therapy on EPC function demonstrated that EPCs exposed to EPO exhibit PI3K/Akt-dependent increases in proliferation, colony formation, and adhesion [40, 41]. Our study shows that plasma levels of EPO significantly increase in parallel with changes in EPC proliferative capacity following exercise, suggesting a possible mechanism for these functional changes.

The literature suggests that EPCs are capable of augmenting neovascularization in both animal models and humans. Currently, it remains to be elucidated whether these progenitors promote new blood vessel formation via differentiation into endothelial cells and engraftment into neovessels [42, 43] or by the release of pro-angiogenic soluble factors [7, 8, 44, 45] or a combination of both. EPCs isolated 10 minutes and 24 hours after exercise displayed similarly increased propensities for endothelial differentiation compared to pre-exercise samples. EPCs collected after exercise also demonstrated both increased secretion of the growth factors VEGF and EPO and augmented responses to hypoxia. These findings are independent of the proliferation data as cells were seeded in equal numbers for these assays. As circulating EPC numbers do not increase until one day after exercise, the immediate systemic cytokine changes induced by exercise appear to stimulate existing circulating EPCs towards a more pro-vascular phenotype. These findings are consistent with results of ex vivo priming of EPCs with SDF-1α, which have demonstrated that incubation of EPCs with recombinant SDF-1α for as little as one minute results in dose-dependent increases in differentiation, transcription of VEGF and enhanced therapeutic potential in a hind-limb ischemia model [46].

Other work investigating the effects of exercise on circulating EPCs in healthy subjects has demonstrated immediate increases in peripheral EPC levels, whereas no difference was observed in our study until 24 hours post-exercise [32, 47]. This discrepancy between findings may be explained by differing definitions of EPCs. In one study AC133+/CD144+ cells were termed EPCs while CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells were defined as EPCs in another. To avoid including monocytes with an angiogenic phenotype, which have been confused with EPCs, but are a distinct cell population [48–50], we have chosen to use VEGFR2+/CD11b−/CD34+/AC133+ as the cell-surface profile in this investigation. By depleting monocytes, we may be excluding the early-mobilized cells seen in other studies, but are focusing on a more specific EPC population. Our in vitro colony formation data closely correspond to circulating EPC numbers, according to our definition, suggesting that this combination is a representative marker profile.

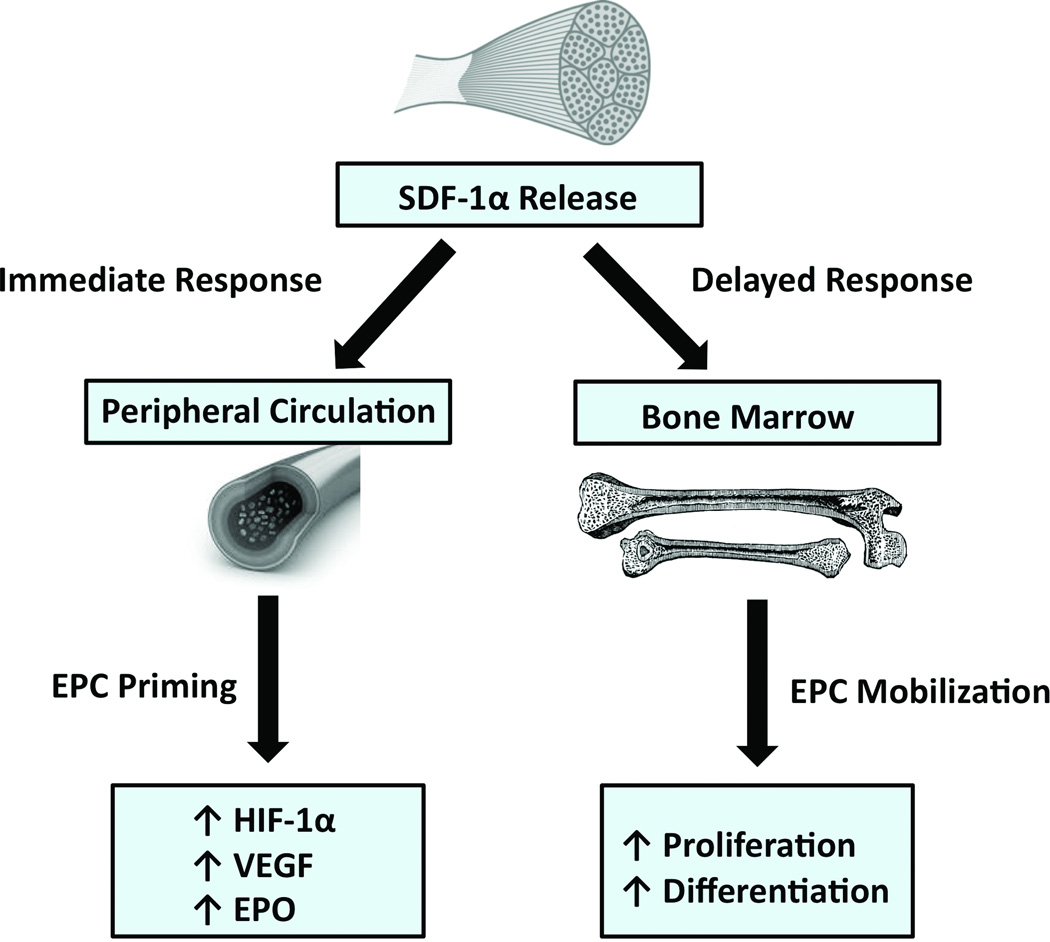

Investigators have demonstrated that aerobic exercise can lead to increased circulating levels of EPCs [16, 32]. However, the mechanism behind this mobilization and the biological characteristics of exercise-induced EPCs have not been examined. We propose that exercise induces an acute elevation of systemic SDF-1α levels that has both immediate and delayed beneficial effects. Existing circulating EPCs become “primed” by exposure to this chemokine, leading to cells with increased function and expression of hypoxia responsive genes. Later, EPC numbers increase as a function of SDF-1α/CXCR4 mediated mobilization. These newly mobilized EPCs are characterized by EPO-mediated increased proliferative capacity and differentiation potential as well as HIF-1α stabilization (Figure 6). These findings build on previous work by establishing that exercise is not only capable of mobilizing endothelial progenitor cells to the circulation, but induces progenitor cells with increased pro-angiogenic characteristics. This suggests a possible mechanism for the regenerative effects seen by physical exercise and also supports the importance of ongoing research in exploring ex vivo modulation of endothelial progenitor cells to maximize their potential for cell-based therapy. However, it is to be determined how baseline fitness of different individuals and increasing levels of exercise would affect EPC mobilization and function. More intense levels or longer periods of physical exercise could potentially influence these results. Further studies are needed to define exercise regimens yielding an ideal ratio of physical activity and EPC mobilization that are feasible for a majority of patients.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the downstream effects of physical exercise. Exercise initiates an immediate release of SDF-1α from ischemic skeletal muscle, which has both immediate and delayed effects. In the immediate post-exercise period, systemic SDF-1α “primes” circulating EPCs, augmenting their paracrine activity. A delayed effect is also observed after 24 hours with mobilization of an EPC population with increased proliferative, differentiation, and secretory capacity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Sources

This work was supported by grant no. RO1-DK-074095 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and grant no. RO1-AG-025016 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

E.C. and J.P. contributed equally to this work. E.C. and J.P. designed and performed experiments. D.D., Z.N.M., J.S.C., M.J, M.R. and R.C.R. analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. S.B., A.J.W. and A.J.W. collected data. M.T.L. and G.C.G. supervised the project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asahara T, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. SCIENCE. 1997;275(5302):964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumpold H, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells: a source for therapeutic vasculogenesis? J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8(4):509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tepper OM, et al. Adult vasculogenesis occurs through in situ recruitment, proliferation, and tubulization of circulating bone marrow-derived cells. Blood. 2005;105(3):1068–1077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceradini DJ, et al. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nature medicine. 2004;10(8):858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceradini DJ, et al. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crosby JR, et al. Endothelial cells of hematopoietic origin make a significant contribution to adult blood vessel formation. Circ Res. 2000;87(9):728–730. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbich C, et al. Soluble factors released by endothelial progenitor cells promote migration of endothelial cells and cardiac resident progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39(5):733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehman J, et al. Peripheral blood "endothelial progenitor cells" are derived from monocyte/macrophages and secrete angiogenic growth factors. Circulation. 2003;107(8):1164–1169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000058702.69484.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavakis E, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Homing and engraftment of progenitor cells: a prerequisite for cell therapy. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2008;45(4):514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin Y, et al. AMD3100 mobilizes endothelial progenitor cells in mice, but inhibits its biological functions by blocking an autocrine/paracrine regulatory loop of stromal cell derived factor-1 in vitro. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology. 2007;50(1):61–67. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3180587e4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hristov M, et al. Regulation of endothelial progenitor cell homing after arterial injury. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wojakowski W, Tendera M. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute coronary syndromes. Folia histochemica et cytobiologica / Polish Academy of Sciences, Polish Histochemical and Cytochemical Society. 2005;43(4):229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin Y, et al. AMD3100 mobilizes endothelial progenitor cells in mice, but inhibits its biological functions by blocking an autocrine/paracrine regulatory loop of stromal cell derived factor-1 in vitro. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50(1):61–67. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3180587e4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hristov M, et al. Regulation of endothelial progenitor cell homing after arterial injury. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98(2):274–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wojakowski W, Tendera M. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute coronary syndromes. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2005;43(4):229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laufs U, et al. Physical training increases endothelial progenitor cells, inhibits neointima formation, and enhances angiogenesis. Circulation. 2004;109(2):220–226. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109141.48980.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehman J, et al. Exercise acutely increases circulating endothelial progenitor cells and monocyte-/macrophage-derived angiogenic cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(12):2314–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill JM, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348(7):593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gram AS, et al. Compliance with physical exercise: Using a multidisciplinary approach within a dose-dependent exercise study of moderately overweight men. Scand J Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1403494813504505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehling UM, et al. In vitro differentiation of endothelial cells from AC133-positive progenitor cells. Blood. 2000;95(10):3106–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peichev M, et al. Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood. 2000;95(3):952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamoto A, Asahara T. Role of progenitor endothelial cells in cardiovascular disease and upcoming therapies. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2007;70(4):477–484. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Povsic TJ, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Endothelial progenitor cells: markers of vascular reparative capacity. Therapeutic advances in cardiovascular disease. 2008;2(3):199–213. doi: 10.1177/1753944708093412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tepper OM, et al. Human endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation. 2002;106(22):2781–2786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039526.42991.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loomans CJ, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(1):195–199. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JZ, et al. Number and activity of endothelial progenitor cells from peripheral blood in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;107(3):273–280. doi: 10.1042/CS20030389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasa M, et al. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001;89(1):E1–E7. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rauscher FM, et al. Aging, progenitor cell exhaustion, and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2003;108(4):457–463. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000082924.75945.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Q, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells, cardiovascular risk factors, cytokine levels and atherosclerosis--results from a large population-based study. PloS one. 2007;2(10):e975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blumenthal JA, et al. Effects of exercise and stress management training on markers of cardiovascular risk in patients with ischemic heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1626–1634. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon NF, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention; the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; the Stroke Council. Stroke. 2004;35(5):1230–1240. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000127303.19261.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehman J, et al. Exercise acutely increases circulating endothelial progenitor cells and monocyte-/macrophage-derived angiogenic cells. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43(12):2314–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner S, et al. Endurance training increases the number of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with cardiovascular risk and coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181(2):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams V, et al. Increase of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease after exercise-induced ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(4):684–690. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000124104.23702.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratajczak MZ, et al. Expression of functional CXCR4 by muscle satellite cells and secretion of SDF-1 by muscle-derived fibroblasts is associated with the presence of both muscle progenitors in bone marrow and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in muscles. Stem Cells. 2003;21(3):363–371. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-3-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gustafsson T, et al. Exercise-induced expression of angiogenesis-related transcription and growth factors in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(2 Pt 2):H679–H685. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ameln H, et al. Physiological activation of hypoxia inducible factor-1 in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2005;19(8):1009–1011. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2304fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundby C, Gassmann M, Pilegaard H. Regular endurance training reduces the exercise induced HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle in normoxic conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;96(4):363–369. doi: 10.1007/s00421-005-0085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Falco E, et al. SDF-1 involvement in endothelial phenotype and ischemia-induced recruitment of bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104(12):3472–3482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.George J, et al. Erythropoietin promotes endothelial progenitor cell proliferative and adhesive properties in a PI 3-kinase-dependent manner. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68(2):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahlmann FH, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation is regulated by erythropoietin. Kidney Int. 2003;64(5):1648–1652. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hur J, et al. Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):288–293. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000114236.77009.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoon CH, et al. Synergistic neovascularization by mixed transplantation of early endothelial progenitor cells and late outgrowth endothelial cells: the role of angiogenic cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Circulation. 2005;112(11):1618–1627. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Santo S, et al. Novel cell-free strategy for therapeutic angiogenesis: in vitro generated conditioned medium can replace progenitor cell transplantation. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gnecchi M, et al. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103(11):1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zemani F, et al. Ex vivo priming of endothelial progenitor cells with SDF-1 before transplantation could increase their proangiogenic potential. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28(4):644–650. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Craenenbroeck EM, et al. A maximal exercise bout increases the number of circulating CD34+/KDR+ endothelial progenitor cells in healthy subjects. Relation with lipid profile. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(4):1006–1013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01210.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaughan EE, O'Brien T. Isolation of circulating angiogenic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;916:351–356. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-980-8_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q, et al. Coculture with Late, but Not Early, Human Endothelial Progenitor Cells Up Regulates IL-1 beta Expression in THP-1 Monocytic Cells in a Paracrine Manner. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013:859643. doi: 10.1155/2013/859643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deak E, et al. Bone marrow derived cells in the tumour microenvironment contain cells with primitive haematopoietic phenotype. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(7):1946–1952. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.