Significance

VEGF/VEGFR and Notch signaling pathways are major molecular regulators of sprouting angiogenesis. Here we investigated the cross-talk between VEGFR and Notch signaling by using state-of-the-art inducible genetic mouse models. We found that VEGFR2 is absolutely required for the sprouting of endothelial cells that display low Notch activity. VEGFR3 cannot rescue the angiogenic sprouting associated with loss of Notch signaling. On the other hand, postnatal lymphangiogenesis required VEGFR3, but not VEGFR2. Because several new VEGF/VEGFR and Notch modulators are in clinical trials for the treatment of angiogenesis-related diseases, it is of the utmost importance to understand the signaling relationships of VEGFRs. This should also facilitate the design of more effective multitargeted treatments.

Keywords: Notch, lymphangiogenesis, anti-angiogenesis, VEGFC, VEGFD

Abstract

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, is regulated by vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) and their receptors (VEGFRs). VEGFR2 is abundant in the tip cells of angiogenic sprouts, where VEGF/VEGFR2 functions upstream of the delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4)/Notch signal transduction pathway. VEGFR3 is expressed in all endothelia and is indispensable for angiogenesis during early embryonic development. In adults, VEGFR3 is expressed in angiogenic blood vessels and some fenestrated endothelia. VEGFR3 is abundant in endothelial tip cells, where it activates Notch signaling, facilitating the conversion of tip cells to stalk cells during the stabilization of vascular branches. Subsequently, Notch activation suppresses VEGFR3 expression in a negative feedback loop. Here we used conditional deletions and a Notch pathway inhibitor to investigate the cross-talk between VEGFR2, VEGFR3, and Notch in vivo. We show that postnatal angiogenesis requires VEGFR2 signaling also in the absence of Notch or VEGFR3, and that even small amounts of VEGFR2 are able to sustain angiogenesis to some extent. We found that VEGFR2 is required independently of VEGFR3 for endothelial DLL4 up-regulation and angiogenic sprouting, and for VEGFR3 functions in angiogenesis. In contrast, VEGFR2 deletion had no effect, whereas VEGFR3 was essential for postnatal lymphangiogenesis, and even for lymphatic vessel maintenance in adult skin. Knowledge of these interactions and the signaling functions of VEGFRs in blood vessels and lymphatic vessels is essential for the therapeutic manipulation of the vascular system, especially when considering multitargeted antiangiogenic treatments.

The VEGF/VEGFR and Notch signal transduction pathways are key elements of blood vessel formation in physiological and pathological conditions. VEGFR2 is expressed in blood vascular endothelial cells, where it stimulates endothelial proliferation, migration, survival, and vascular permeability (1). Vegfr2 gene-targeted mice die at embryonic day (E) 8.5 because of lack of vasculogenesis (2) and inhibitors blocking the VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway are used to inhibit pathological angiogenesis in patients with cancer or age-related macular degeneration (3). VEGFR3 is also required for developmental angiogenesis and Vegfr3−/− mice die at E9.5 because of cardiovascular remodeling defects (4). When development progresses, VEGFR3 becomes restricted to lymphatic endothelial cells (5). In adults, VEGFR3 expression is very low or absent in most blood vessels, but detectable in e.g., high endothelial venules and fenestrated capillaries (6). VEGFR3 expression is up-regulated in angiogenic endothelial cells, for example in the tumor vasculature, and it is often highly expressed in endothelial tip cells (7–10).

Several studies have highlighted the importance of Notch signaling in arteriovenous differentiation and tip cell selection during angiogenesis in mice and zebrafish (11), and VEGFR and Notch signals are tightly coordinated during angiogenic sprouting. VEGFR2, which is expressed in endothelial tip cells, activates Notch in adjacent endothelial cells via VEGF-induced up-regulation of delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4), but it is not clear to what extent VEGFR2 expression is suppressed by the DLL4/Notch signals from neighboring cells (12–15). VEGFC/VEGFR3 signaling activates Notch in blood vascular endothelial cells, facilitating the conversion of tip cells to stalk cells during the stabilization of vascular loops (16). Notch, in turn, regulates VEGFR3 expression in zebrafish and in postnatal mice (7, 8, 17).

An important question regarding VEGFR signaling is the cross-talk between VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 during vessel morphogenesis. VEGFR2/VEGFR3 heterodimers in endothelial cells are important for angiogenic sprouting in mice and arteriogenesis in zebrafish (18, 19). VEGFR2 activation induces VEGFR3 expression in blood vessels and silencing of the VEGFR3 gene prolongs VEGFR2 phosphorylation in human blood vascular endothelial cells in culture (7, 16). Previous studies used VEGFR2 deletion in combination with poorly characterized tyrosine kinase inhibitors to probe the cross-talk of the receptors (20). However, the functions and interactions of the VEGFRs have not been validated by simultaneous genetic deletions in mice so far. To circumvent the embryonic lethality in Vegfr2−/− and Vegfr3−/− mice, we deleted VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 conditionally in newborn pups to analyze postnatal sprouting angiogenesis.

Results

Postnatal Angiogenesis, but Not Lymphangiogenesis, Relies on VEGFR2 in a Dose-Dependent Manner.

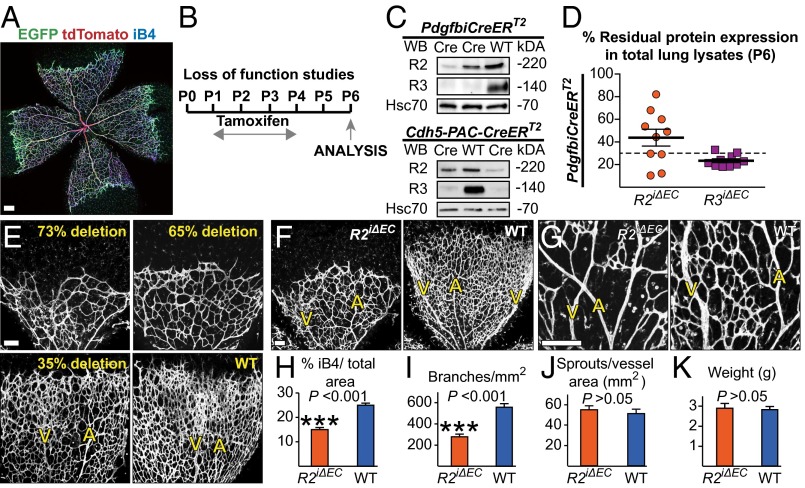

To generate inducible, endothelial-specific mouse mutants for VEGFR2 and VEGFR3, we cross-bred PdgfbiCreERT2 (21) and Cdh5-PAC-CreERT2 (22) mice with mice homozygous for the conditional Vegfr2 (23) (Vegfr2flox/flox) and Vegfr3 (24) (Vegfr3flox/flox) alleles (Vegfr2iΔEC, Vegfr3iΔEC, and Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC, respectively). Tamoxifen-treatment of PdgfbiCreERT2 mice selectively targeted genes in the endothelial cells of postnatal retinal blood vessels (Fig. 1A). Following tamoxifen administration from postnatal day 1 (P1) to P4 (Fig. 1B), the Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC mice displayed various degrees of VEGFR2 deletion at P6 in Western blot analysis of total lung lysates (10–82% of VEGFR2 remaining, mean: 43% ± 7 SEM), whereas VEGFR3 deletion was regularly consistent (21–33% of VEGFR3 remaining, mean: 25% ± 1 SEM) (Fig. 1 C and D). The degree of VEGFR2 deletion in the lungs correlated with the degree of deletion in the endothelial fraction of the corresponding retinas, and with the severity of the retinal vascular phenotype (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1 A and B). Analysis of Vegfr2iΔEC retinas that had an ∼60% reduction of VEGFR2 protein levels revealed a hypoplastic vasculature (20) and occasional arteriovenous intercrosses at P6 (Fig. 1 F–J), but no differences in the growth of the mice during the 6-d time period analyzed (Fig. 1K). We have previously shown that Cre-mediated recombination in the retinas of PdgfbiCreERT2;Rosa26R reporter mice is gradual and complete within 48 h of tamoxifen induction (16). This time window and the half-life of the protein could therefore prolong the receptor’s signaling potential (25). Importantly, we observed a smaller decrease of VEGFR2 than VEGFR3 after 24 h of tamoxifen treatment (64–91% VEGFR2 remaining, mean: 76% ± 8 SEM vs. 36–62% VEGFR3 remaining, mean: 46% ±5 SEM) (Fig. S1C). We therefore considered that the low and variable efficiency of VEGFR2 deletion could produce a population of endothelial cells expressing different amounts of VEGFR2 and that endothelial cells that failed to undergo recombination could display a competitive advantage in assuming the tip cell phenotype (14).

Fig. 1.

Validation of Cre-mediated VEGFR recombination in iΔEC mice. (A) PdgfbiCreERT2-IRES-EGFP expression (in green) in blood vascular endothelial cells (isolectin B4, iB4, in blue), and recombination of the targeted allele (red fluorescent tdTomato) in the retinas of PdgfbiCreERT2;Rosa26Tdt P5 pups. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (B) A schematic of the tamoxifen administration regime used in the VEGFR loss-of-function studies, unless otherwise indicated. (C) Western blots of total lung lysates from Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC pups deleted with two different Cre lines. Tamoxifen treatment results in a strong decrease of VEGFR3 protein in total lung lysates in the Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC mice, but the extent of VEGFR2 deletion varies. (D) Quantification of Western blot VEGFR2 signal densities from two litters of PdgfbiCreERT2;Vegfr2flox/flox;Vegfr3flox/flox mice. Only mice with at least 70% decrease in protein levels were included in the study (indicated by the dashed line). (E) The severity of the retinal phenotype correlates with the amount of VEGFR2 deletion in the lung. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (F–J) Vascular defects in Vegfr2iΔEC retinas of pups with an average 60% protein deletion in total lung lysates. (F and G) iB4 staining (white) of P6 Vegfr2iΔEC and wild-type littermate retinas. Note the arteriovenous crossing in G. A, artery; V, vein. (Scale bars, 100 μm in F and 50 μm in G.) (H–J) Quantitative analysis of the retinas shown in F. (K) Weight of Vegfr2iΔEC pups at P6. Error Bars: SEM. ***P < 0.001. n ≥ 3. Deleter in E–K: PdgfbiCreERT2.

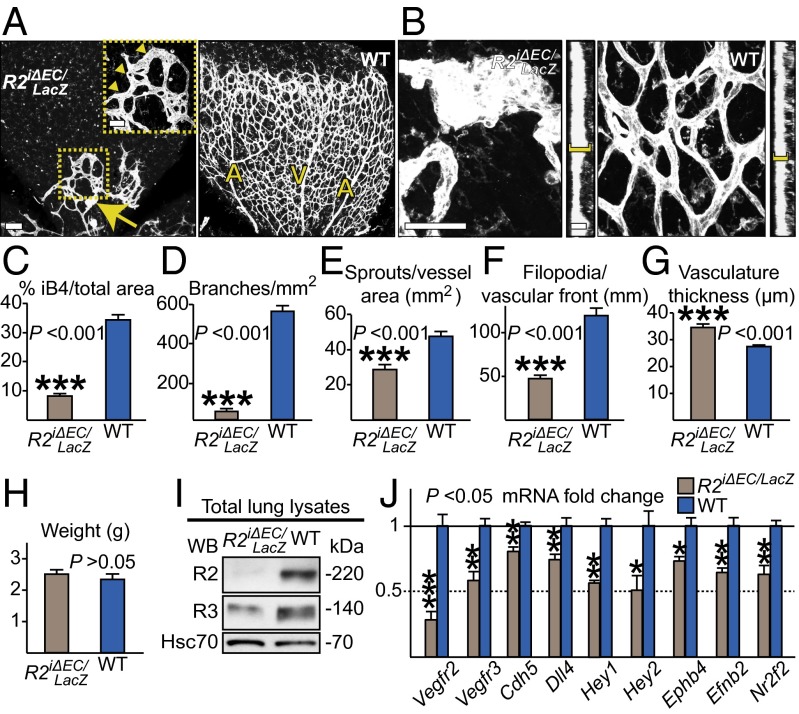

To maximize VEGFR2 deletion, we generated PdgfbiCreERT2;Vegfr2flox/LacZ mice (Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ), in which one allele of Vegfr2 is conditional and the other one is constitutively deleted (2). Although Vegfr2 happloinsufficiency had no overt impact on postnatal retinal vascularization (Fig. S1 D–H), tamoxifen administration during P1–P4 to the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ pups resulted in a further decrease of retinal vessel density [from 40% in Vegfr2iΔEC retinas (Fig. 1H) to 76%], but not body weight (Fig. 2 A, C, D, and H). The Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ retinas showed significantly reduced endothelial sprouting and filopodia formation (Fig. 2 E and F), resulting in a “flat” vascular front (arrowheads in Fig. 2A), reminiscent of loss of the retinal VEGF gradient (13, 26). We observed clusters of endothelial cells (Fig. 2 B and G), which suggested disrupted tip/stalk cell differentiation and endothelial cell competition because of low receptor levels (14). VEGFR3 mRNA and protein were decreased, indicating that VEGFR2 signals are upstream of VEGFR3 expression in the blood vessels (7, 20) (Fig. 2 I and J).

Fig. 2.

VEGFR2 signaling is indispensable for postnatal angiogenesis. (A) Visualization of blood vessels in Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ and WT littermate retinas at P6 by iB4 staining (white). The squared area is shown in magnification in the Inset, and the arrowheads indicate the flat angiogenic front. An endothelial cell cluster (arrow) is shown in higher magnification in B. Note the increased thickness of the retinal vasculature at the sites of clustering (yellow brackets in the sagittal sections in B, quantification in G). (Scale bars: 100 μm for A, 50 μm for the Inset in A, 50 μm for B, and 10 μm for the sagittal sections in B). (C–F) Statistical analysis of the indicated parameters of the retinas shown in A. (H) Weight of the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ pups at P6. (I) Western blotting of VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 in lung lysates from Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ and control WT pups. (J) Fold-changes of the expression of the indicated endothelial genes, analyzed by real-time quantitation using RNA from lungs of Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ and WT littermate pups at P6. The data were normalized to endogenous control Gapdh, and to Pecam1 to compensate for decreased endothelial cell numbers in the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ pups. Error Bars: SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n ≥ 3. Deleter: PdgfbiCreERT2.

Dll4 mRNA levels were decreased, in agreement with reduced endothelial tip cell numbers in the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ retinas, thus leading to reduced Notch activation. This finding was reflected in the mRNA levels of the Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2. In addition, the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ retinas showed defective arteriovenous differentiation with decreased expression of several key genes involved in arteriovenous identity, such as EphB4, EphrinB2, and Nr2f2 (Fig. 2J). This finding is consistent with disturbed VEGF/Notch signaling, as shown in zebrafish and mouse embryos (27–29). All mRNA levels were normalized against the endogenous control Gapdh and then against the endothelial-specific platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (Pecam1) mRNA to compensate for the decreased endothelial cell numbers in the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ pups. The differences in the phenotypes of the Vegfr2iΔEC and Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ retinas suggest that small amounts of VEGFR2 can support angiogenesis to some degree. Importantly, they show that the loss of VEGFR2 results in reduced Notch signaling without a hypervascular phenotype.

VEGFR2 Is Required for the Hypersprouting Associated with VEGFR3 Deletion.

We have previously shown that VEGFR3 deletion from the angiogenic blood vessel endothelium results in a hypervascular phenotype because of loss of the ligand-independent VEGFR3 signals and consequent failure to activate Notch (16). We next studied the effects of combined endothelial deletion of VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 during postnatal angiogenesis by generating PdgfbiCreERT2;Vegfr2flox/LacZ;Vegfr3flox/flox, (Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ;Vegfr3iΔEC), and PdgfbiCreERT2;Vegfr2flox/flox;Vegfr3flox/flox (Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC) mice. Because Cre activation starting at P1 resulted in increased lethality in the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ;Vegfr3iΔEC mice by P6, we decided to focus our analysis on Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC pups that were carefully selected for successful VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 deletion (at least 70% decreased receptor protein in lung lysates) (Fig. S2A).

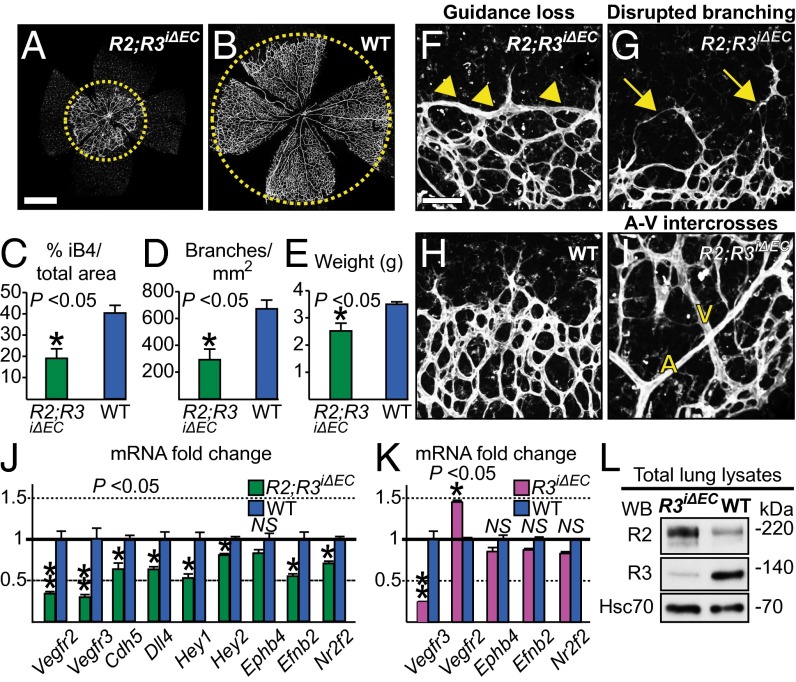

Genetic ablation of both receptors severely impaired retinal angiogenesis, resulting in vascular hypoplasia and reduced vessel branching (Fig. 3 A–D). This finding indicated that VEGFR2 deletion, similarly to VEGFR2 blocking antibodies (16), is able to suppress the hypersprouting associated with the loss of VEGFR3. The Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC retinas displayed areas of reduced sprouting, consistent with the loss of VEGFR2 signals (26), as well as disrupted branching and endothelial cell detachment at the vascular front, similar to what has been reported in the Vegfc+/− retinas (16) (Fig. 3 F–H). Thus, loss of both VEGFC receptors mimicked the loss of VEGFC in this developmental context. We also observed arterial-venous intercrosses (Fig. 3I). The same defects could be observed in the retinas of the surviving Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ;Vegfr3iΔEC pups and in pups deleted of VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 by using the VE-cadherin promoter-driven inducible Cre (22) (Fig. S2 B–I). The compound-deleted pups weighed 28% less than their control littermates, indicating the severity of the phenotype (Fig. 3E). Analysis of lung lysates confirmed substantially decreased Vegfr2 and Vegfr3 expression, as well as decreased Dll4, Hey1, Hey2, EphrinB2, and Nr2f2 mRNAs, after normalization against both Gapdh and Pecam1 (Fig. 3J). Importantly, we did not observe arteriovenous specification defects in the Vegfr3iΔEC retinas, either by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4 A and B) or by gene-expression analysis (Fig. 3K), suggesting that the arteriovenous defects are a result of VEGFR2 deletion. VEGFR2 mRNA and protein levels were significantly up-regulated following VEGFR3 deletion (Fig. 3 K and L), pointing to a feedback loop, where VEGFR2 induces VEGFR3, which then acts to suppress VEGFR2 expression.

Fig. 3.

Vascular and gene expression defects in the Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC retinas. (A and B) Visualization of the retinal vasculature by iB4 staining (white) in Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC and control wild-type littermate retinas at P6. (C and D) Quantification of vascular parameters from the retinas shown in A and B. (E) Weight of the pups. (F–I) High magnification imaging of the retinas. Note the flat angiogenic front (arrowheads in F), failed vessel branching (arrows in G), and the arteriovenous crossing in (I). A, artery; V, vein. Comparison of the retinal phenotypes of VEGFR2, VEGFR3, and compound-deleted pups is shown in the top panels of Fig. 4 A–D, Figs. S3 A–D, and Fig. S4. (J) Fold-changes in the expression of the indicated endothelial genes. (K) mRNA analysis of lung lysates from Vegfr3iΔEC and wild-type littermate pups at P6. Note that Vegfr3 deletion results in the up-regulation of Vegfr2 mRNA, but has no effect on the EphB4, EphrinB2, or Nr2f2 mRNAs. The gene-expression data were normalized to the endogenous control Gapdh to compensate for experimental variations, and then to Pecam1, to compensate for alterations in endothelial cell numbers. (L) VEGFR2 protein is up-regulated in the Vegfr3iΔEC lungs, indicating that VEGFR3 normally suppresses VEGFR2 expression. Error bars: SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n ≥ 3. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) Deleter: PdgfbiCreERT2.

Fig. 4.

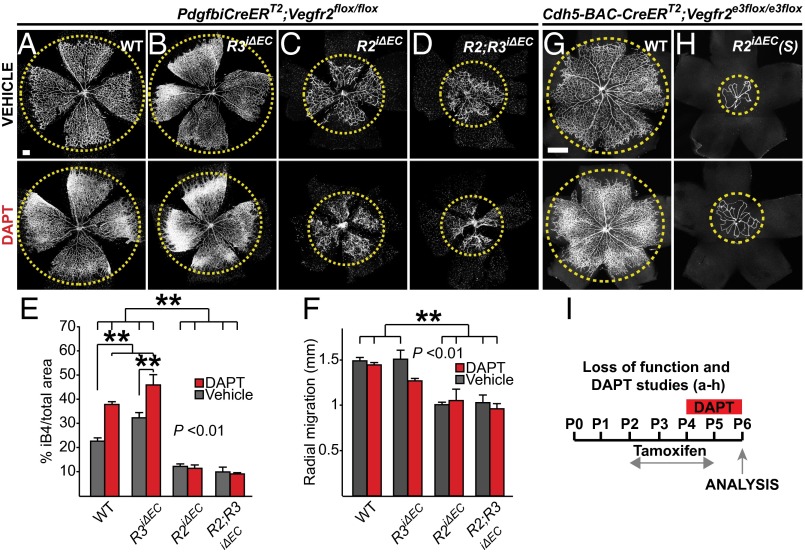

VEGFR2 signaling is required for endothelial hypersprouting in response to Notch inactivation by DAPT. (A–D) Low-magnification images of P6 retinas of the indicated mice treated with DAPT or vehicle, and stained for iB4. The yellow circles highlight the vascular front progression. (Scale bars, 200 μm.) (E) Statistical analysis of the retinas shown in Fig. S3 A–D. (F) Statistical analysis of the extent of radial migration of the vascular front from the optic stalk shown in A–D. Note the significantly decreased vascular area in the absence of VEGFR2, even after DAPT treatment. Error bars: SEM. **P < 0.01. n ≥ 3. Deleter in A–D: PdgfbiCreERT2. (G and H) Low-magnification images of P6 retinas stained for PECAM1 (in white), following pharmacological inhibition of Notch (DAPT) plus concurrent deletion of VEGFR2, using an independent line of Vegfr2iΔEC(S) mice (Cdh5-BAC-CreERT2;Vegfr2e3flox/e3flox). (Scale bars, 400 μm.) (I) The tamoxifen and DAPT administration regimes used in the experiments shown in the figure.

Notch Inhibition Promotes Angiogenesis in the Absence of VEGFR3 but Not in the Absence of VEGFR2.

To investigate the interplay between VEGFR2, VEGFR3, and Notch signaling in postnatal angiogenesis, we inhibited Notch activation by injecting a γ-secretase inhibitor (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester; DAPT) to the Vegfr2iΔEC, Vegfr3iΔEC, and Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC pups during P4–P5, followed by analysis at P6 (Fig. 4I). VEGFR3 deletion starting at P2 aggravated the hypervascularity because of Notch inhibition and decreased slightly the migration of the vascular front, similarly to what has been described in the Dll4+/− mutant mice (13) (Fig. 4 A, B, E, and F, and Fig. S3 A and B). These results indicated that VEGFR3 deletion recapitulates the Notch loss of function phenotype. In contrast to previous reports (20), genetic ablation of VEGFR2 alone or in combination with VEGFR3 prevented completely the increase of vascular density induced by DAPT treatment (Fig. 4 C–E and Fig. S3 C and D), indicating that VEGFR2 but not VEGFR3 is required for the hypersprouting that occurs in the absence of Notch activation. In both cases, the vasculature showed severe defects, similar to those observed in the DAPT-untreated Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC mice, including lack of sprouting at the vascular front and endothelial cell detachment (Fig. S3 E–I). Furthermore, VEGFR2 deletion suppressed the radial migration of the vascular front in all conditions (Fig. 4F).

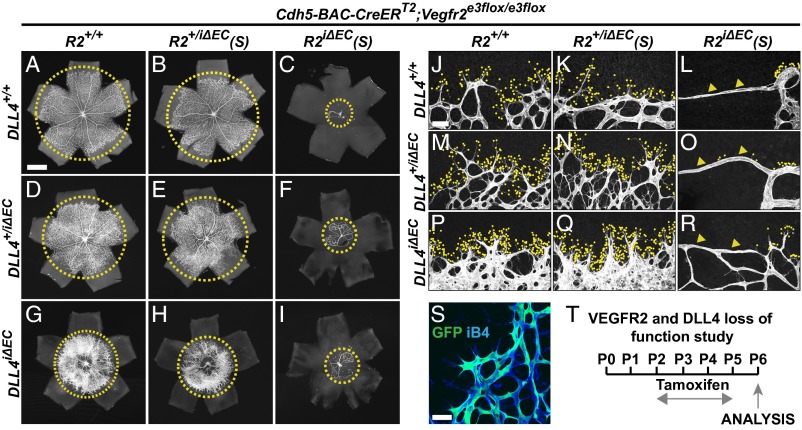

We confirmed that VEGFR2 is necessary for the Notch loss-of-function–associated hypersprouting by using an independent system for conditional deletion of VEGFR2 in the endothelium, which achieves a high degree of VEGFR2 recombination (Cdh5-BAC-CreERT2;Vegfr2e3flox/e3flox), termed hereafter Vegfr2iΔEC(S) (30, 31) (Fig. 5S). Genetic deletion of VEGFR2 reduced postnatal sprouting angiogenesis in the retina in the presence or absence of DAPT (Fig. 4 G–I). Because DAPT affects all cell types in the developing retina, we further confirmed the results in compound mice lacking endothelial DLL4 and VEGFR2 by crossing the Vegfr2iΔEC(S) mice with Dll4flox/flox mice (32) (Fig. 5T). Dll4iΔEC;Vegfr2iΔEC(S) and Dll4+/iΔEC;Vegfr2iΔEC(S) retinas were unable to sprout despite the low Notch signaling, similarly to the Vegfr2iΔEC and Vegfr2iΔEC(S) retinas treated with DAPT (Fig. 5 A, C, D, F, G, I, J, L, M, O, P, and R). However, heterozygous VEGFR2 levels allowed hypersprouting in the retinas of compound Dll4+/iΔEC;Vegfr2+/iΔEC(S) and Dll4iΔEC;Vegfr2+/iΔEC(S) pups (Fig. 5 B, E, H, K, N, and Q), supporting our finding that residual levels of VEGFR2 can sustain hypersprouting upon loss of Notch signaling.

Fig. 5.

VEGFR2 signaling is indispensable for endothelial hypersprouting in Dll4iΔEC retinas. (A–R) Low (A–I) and high (J–R) magnification images of retinas from P6 pups, harboring various combinations of endothelial-specific deletions of DLL4 and VEGFR2. PECAM1 staining (in white) was used to visualize blood vessels. Note that a 50% reduction of VEGFR2 in Vegfr2+/iΔEC(S) mice allows hypersprouting in Dll4+/iΔEC and Dll4iΔEC mice. The yellow circles in A–I highlight the vascular front progression and the yellow dots in J–R indicate filopodia in the vascular front. Arrowheads in (L, O, and R) point at the flat vascular front. (Scale bars: 500 μm for A–I and 50 μm for J–R.) (S) GFP expression (in green) in blood vascular endothelial cells (iB4 in blue) showing recombination of the targeted allele in the retinas of Cdh5-BAC-CreERT2;GAC-CAT-EGFP P6 pups. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (T) The tamoxifen administration regime used in the experiments shown in the figure. Deleter: Cdh5-BAC-CreERT2. VEGFR2 conditional mouse: Vegfr2e3flox/e3flox.

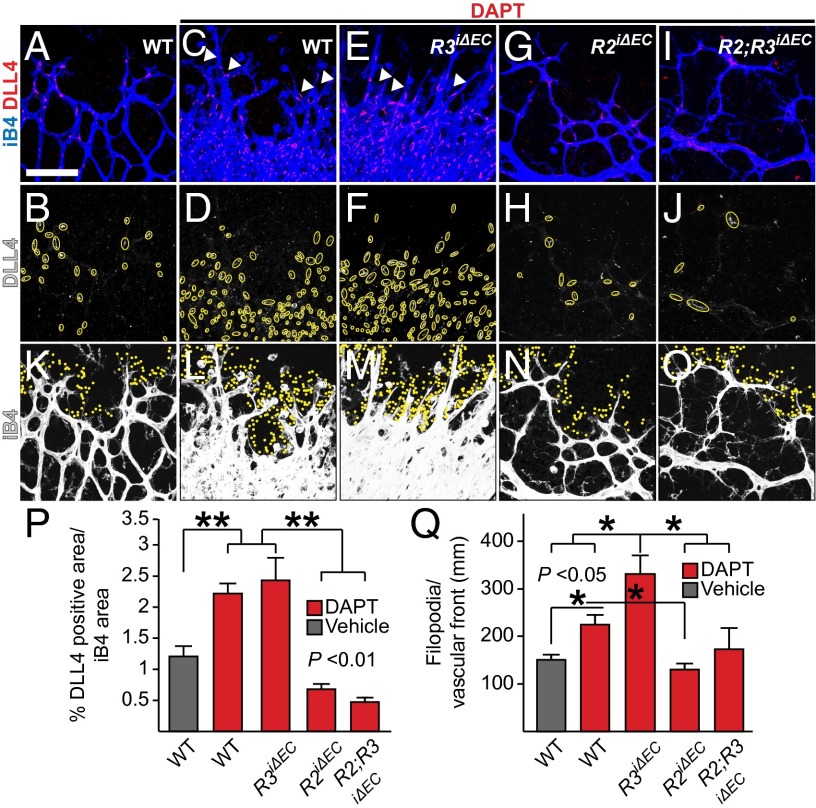

In agreement with previous findings, Notch inhibition resulted in widespread DLL4 expression in the retina, which appeared as intracellular accumulation of DLL4 staining in a “salt and pepper” distribution (Fig. 6 A–D and P). Deletion of VEGFR3 in combination with DAPT did not alter this pattern further (Fig. 6 E, F, and P). In contrast, genetic deletion of VEGFR2 restricted DLL4 induction independently of VEGFR3 deletion (Fig. 6 G–J, and P). Notch inhibition in wild-type pups resulted in increased number of filopodia protrusions at the vascular front, consistent with elevated numbers of tip cells (33) (Fig. 6 K, L, and Q), and simultaneous conditional deletion of VEGFR3 further increased the number of filopodia (Fig. 6 M and Q). However, VEGFR2 deletion limited the number of filopodia in both conditions back to the levels observed in vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Fig. 6 N, O, and Q). In the absence of DAPT, VEGFR2 deletion reduced the numbers of filopodia and DLL4 expression (Fig. S4). Compound deletion of VEGFR3 and VEGFR2 rescued the filopodia back to wild-type numbers, but did not rescue the levels of DLL4 protein in the VEGFR2 mutants (Fig. S4). Thus, filopodia extension is limited by VEGFR3/Notch signals, but promoted by VEGFR2, and DLL4 expression is induced by VEGFR2, but suppressed by VEGFR3 (Fig. S5). Further postnatal analysis of the gene-deleted pups indicated that unlike VEGFR3, VEGFR2 has a minor, if any, function in lymphangiogenesis. VEGFR3, but not VEGFR2, was also required for lymphatic vessel maintenance in adult mice because global ablation of VEGFR3 resulted in lymphatic vessel atrophy (see Supporting Information and Figs. S6–S9).

Fig. 6.

VEGFR2 is required for DLL4 up-regulation and filopodia projection upon Notch inhibition. (A–J) Whole-mount immunostaining for iB4 (in blue) and DLL4 (in red) in retinas of P6 pups of the indicated genotypes, treated with DAPT for 48 h. The yellow circles highlight the DLL4 staining. (P) Quantification of the percentage of DLL4+ area normalized to iB4+ area shown in A–J. Arrowheads in C and E point to bifurcations at the tips of the developing sprouts, presumably as a result of tip cell duplication (40). Note also the altered morphology of the sprouts. (K–O) iB4 staining of the same retinas (in white), overexposed to visualize the filopodia (indicated by yellow dots) at the vascular front. (Q) Quantification of the number of filopodia projections per length of the vascular front. Error bars: SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n ≥ 3. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) Deleter in A–O: PdgfbiCreERT2.

Discussion

In this study, we have used the mouse retina as a model to demonstrate that in VEGF-driven postnatal angiogenesis, VEGFR2 is absolutely required for the sprouting of new vessels. Furthermore, VEGFR3 activity cannot rescue the angiogenic sprouting even when the Notch pathway signaling activity is inhibited (Fig. S5). In fact, the severity of the vascular phenotype is VEGFR2 dose-dependent, and our experiments show that fairly low residual amounts of VEGFR2 can sustain angiogenesis.

Our results, using combinations of three different endothelial specific Cre-recombinases and two different conditional VEGFR2 mouse lines, emphasize the fundamental role of VEGFR2 signaling in endothelial cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, and migration, and highlight the central role of VEGFR2 in Notch-mediated vascular sprouting (34). Although retinas from the PdgfbiCreERT2;Vegfr2wt/flox P6 pups displayed slightly reduced vascularization after tamoxifen induction during P1–P3 (35), there were no statistically significant differences between the Vegfr2+/LacZ and the wild-type littermate mice, suggesting genetic compensation in the case of constitutive heterozysity. Thus, it is unlikely that nonendothelial effects contribute to the phenotypic differences between the Vegfr2iΔEC and Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ mice, although retinal neuronal cells also express VEGFR2 (36). Interestingly, a similar glomeruloid accumulation of endothelial cells as observed here in the Vegfr2iΔEC/LacZ retinas was reported to occur in the aortas of Dll4+/− embryos (37). Disturbed Notch signaling could be also behind the loss of the arterio-venous identity in these retinas because of disrupted VEGF signaling, as has been shown in zebrafish and mouse embryos (29).

Endothelial deletion of VEGFR3 results in a hypervascular retinal phenotype, which can be partially rescued by blocking VEGFR2 signaling with monoclonal antibodies (16). Here we show that genetic deletion of VEGFR3 up-regulates VEGFR2 expression in vivo, establishing a feedback loop where VEGFR2 induces VEGFR3 (20), which then suppresses VEGFR2 expression. Although VEGFR2 deletion completely abolished the hypervascular phenotype resulting from the deletion of VEGFR3, the retinas of the Vegfr2iΔEC;Vegfr3iΔEC pups displayed additional defects reminiscent of mice with VEGFC happloinsufficiency, indicating that the receptors also have nonredundant functions during vessel development. However, it is important to note that ligand stimulation of VEGFR3 can promote angiogenesis, even in the presence of a VEGFR2-blocking antibody (7).

The tip cells project filopodia that integrate directional cues from the endothelial microenvironment. They lead the outgrowing vasculature by migrating toward higher concentrations of the angiogenic factors and by anastomosing with each other to create vascular loops for blood perfusion (26). Pharmacological inhibition of Notch in combination with genetic deletion of VEGFR3 aggravated the hypervascularity and DLL4 up-regulation (13) when deletion was initiated at P2. Thus, using a highly precise method to eliminate VEGFR3 activity in the endothelium, we demonstrate that loss of VEGFR3 function is equivalent to loss of Notch signaling, resulting in excessive filopodia formation and hypersprouting. The DLL4 protein levels remained unaltered in the Vegfr3iΔEC retinas, despite the decreased Dll4 mRNA levels (16). This finding corroborates the idea that VEGFR3 activates Notch in a DLL4-independent noncanonical manner, or that DLL4 up-regulation occurs via VEGFR2-dependent posttranscriptional regulation. On the other hand, we show that the increase of DLL4 in conditions of normal or reduced Notch signaling relies mostly on VEGFR2.

Endothelial cells lacking VEGFR2 were unable to sprout and they showed reduced numbers of filopodia at the vascular front, highlighting the importance of VEGFR2 signaling in endothelial cells. However, VEGFR3 deletion or pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling was able to restore filopodia density back to the wild-type level in Vegfr2iΔEC retinas, suggesting that the endothelial cells can respond to angiogenic stimuli to some degree even without VEGFR2. Our data further suggest that VEGFR2 activates and that VEGFR3/Notch signaling suppresses filopodia extension in endothelial cells. On the other hand, the relative increase in DLL4 and filopodia projections observed in the Vegfr2iΔEC retinas after Notch inhibition emphasizes the existence of other tip cell regulators, such as laminins, in the angiogenic microenvironment (38, 39) (Fig. S5). Although pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling by DAPT inhibits γ-secretase in all retinal cells, our results with the endothelial deletion of DLL4 support the conclusion that VEGFR2 signaling is required for the hypersprouting associated with conditions of reduced DLL4/Notch signaling.

Our study used high-precision genetic models to investigate the cross-talk between VEGFR2, VEGFR3, and Notch signaling in postnatal sprouting angiogenesis. The results obtained differ from previously published ones. Our data implicate VEGFR2 in DLL4 up-regulation and Notch signaling, but fail to confirm that VEGFR3 would be a suppressor of Notch-mediated sprouting (20). The differences may be attributed to the incomplete VEGFR2 deletion and to the specificity of the tools, such as the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, that were used to inactivate VEGFR3 in the previous studies. Although pathological and developmental angiogenesis differ in several aspects, our study provides new understanding of the mechanisms of angiogenesis, which is important for the design of effective multitargeted antiangiogenic therapies.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials and methods can be found in SI Materials and Methods. This research was approved by the Committee for Animal Experiments of the District of Southern Finland. Cre activity was induced in newborn pups with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT; Sigma) during P1–P4 or P2–P5, and the mice were killed at P6, unless stated otherwise. For pharmacological inhibition of Notch, the pups received subcutaneous injections of the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT (Sigma) twice daily during P4 and P5; the control mice received vehicle. Protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting of lung extracts in each mouse, and mean blot densities were quantified using Adobe Photoshop CS5. Gene-expression levels were analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR. The data were normalized to the endogenous control Gapdh to compensate for experimental variations, and for lung tissue also to Pecam1, to compensate for alterations in endothelial cell numbers. Fold-changes were calculated with the comparative CT method. The IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software was used for statistical analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The exact number for each experiment is provided in the SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcus Fruttiger for the PdgfbiCreERT2 mice; Erwin Wagner for the Vegfr2flox/flox mice; Ralf Adams for the Cdh5-PAC-CreERT2 mice; David Shima for the Dll4flox/flox mice; Marius Robciuc and Harri Nurmi for providing tissues of Vegfr3iΔC adult mice; Rui Benedito for discussions; Ralf Adams, Tuomas Tammela, and Wei Zheng for professional comments on the manuscript; The Biomedicum Molecular Imaging Unit for microscopy services; and Katja Salo, Riitta Kauppinen, Tapio Tainola, and the personnel of the Biomedicum Imaging Unit and the Laboratory Animal Center of the University of Helsinki for technical assistance. This study was supported in part by the People Program (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program FP7/2007-2013/ under Grant 317250; the Academy of Finland (Centre of Excellence Program 2014-2019); the European Research Council (ERC-2010-AdG-268804); the Finnish Cancer Research Organization and the Leducq Foundation (11CVD03); grants from the Oskar Öflund Foundation, the Cancer Society of Finland, the Biomedicum Helsinki Foundation, the Maud Kuistila Memorial Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, and the K. Albin Johansson Foundation (all to G.Z.); and a grant from the Ida Montin Foundation (to K.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1423278112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Koch S, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(7):a006502. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shalaby F, et al. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1–deficient mice. Nature. 1995;376(6535):62–66. doi: 10.1038/376062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shojaei F, Ferrara N. Antiangiogenesis to treat cancer and intraocular neovascular disorders. Lab Invest. 2007;87(3):227–230. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumont DJ, et al. Cardiovascular failure in mouse embryos deficient in VEGF receptor-3. Science. 1998;282(5390):946–949. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaipainen A, et al. Expression of the fms-like tyrosine kinase 4 gene becomes restricted to lymphatic endothelium during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(8):3566–3570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Partanen TA, et al. VEGF-C and VEGF-D expression in neuroendocrine cells and their receptor, VEGFR-3, in fenestrated blood vessels in human tissues. FASEB J. 2000;14(13):2087–2096. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-1049com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tammela T, et al. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. Nature. 2008;454(7204):656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature07083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siekmann AF, Lawson ND. Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries. Nature. 2007;445(7129):781–784. doi: 10.1038/nature05577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valtola R, et al. VEGFR-3 and its ligand VEGF-C are associated with angiogenesis in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(5):1381–1390. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65392-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paavonen K, Puolakkainen P, Jussila L, Jahkola T, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 in lymphangiogenesis in wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(5):1499–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbert SP, Stainier DY. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(9):551–564. doi: 10.1038/nrm3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobov IB, et al. Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) is induced by VEGF as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3219–3224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611206104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suchting S, et al. The Notch ligand Delta-like 4 negatively regulates endothelial tip cell formation and vessel branching. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3225–3230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611177104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakobsson L, et al. Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(10):943–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel NS, et al. Up-regulation of delta-like 4 ligand in human tumor vasculature and the role of basal expression in endothelial cell function. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8690–8697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tammela T, et al. VEGFR-3 controls tip to stalk conversion at vessel fusion sites by reinforcing Notch signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(10):1202–1213. doi: 10.1038/ncb2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shawber CJ, et al. Notch alters VEGF responsiveness in human and murine endothelial cells by direct regulation of VEGFR-3 expression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3369–3382. doi: 10.1172/JCI24311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covassin LD, Villefranc JA, Kacergis MC, Weinstein BM, Lawson ND. Distinct genetic interactions between multiple Vegf receptors are required for development of different blood vessel types in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(17):6554–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506886103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson I, et al. VEGF receptor 2/-3 heterodimers detected in situ by proximity ligation on angiogenic sprouts. EMBO J. 2010;29(8):1377–1388. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benedito R, et al. Notch-dependent VEGFR3 upregulation allows angiogenesis without VEGF-VEGFR2 signalling. Nature. 2012;484(7392):110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claxton S, et al. Efficient, inducible Cre-recombinase activation in vascular endothelium. Genesis. 2008;46(2):74–80. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465(7297):483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haigh JJ, et al. Cortical and retinal defects caused by dosage-dependent reductions in VEGF-A paracrine signaling. Dev Biol. 2003;262(2):225–241. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haiko P, et al. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and VEGF-D is not equivalent to VEGF receptor 3 deletion in mouse embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(15):4843–4850. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02214-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waltenberger J, Claesson-Welsh L, Siegbahn A, Shibuya M, Heldin CH. Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(43):26988–26995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerhardt H, et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(6):1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawson ND, et al. Notch signaling is required for arterial-venous differentiation during embryonic vascular development. Development. 2001;128(19):3675–3683. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duarte A, et al. Dosage-sensitive requirement for mouse Dll4 in artery development. Genes Dev. 2004;18(20):2474–2478. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swift MR, Weinstein BM. Arterial-venous specification during development. Circ Res. 2009;104(5):576–588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hooper AT, et al. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okabe K, et al. Neurons limit angiogenesis by titrating VEGF in retina. Cell. 2014;159(3):584–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hozumi K, et al. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205(11):2507–2513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellström M, et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;445(7129):776–780. doi: 10.1038/nature05571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phng LK, Gerhardt H. Angiogenesis: A team effort coordinated by notch. Dev Cell. 2009;16(2):196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sivaraj KK, et al. G13 controls angiogenesis through regulation of VEGFR-2 expression. Dev Cell. 2013;25(4):427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang X, Cepko CL. Flk-1, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), is expressed by retinal progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16(19):6089–6099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06089.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gale NW, et al. Haploinsufficiency of delta-like 4 ligand results in embryonic lethality due to major defects in arterial and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(45):15949–15954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407290101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stenzel D, et al. Endothelial basement membrane limits tip cell formation by inducing Dll4/Notch signalling in vivo. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(11):1135–1143. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Estrach S, et al. Laminin-binding integrins induce Dll4 expression and Notch signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2011;109(2):172–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sainson RC, et al. Cell-autonomous notch signaling regulates endothelial cell branching and proliferation during vascular tubulogenesis. FASEB J. 2005;19(8):1027–1029. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3172fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.