Abstract

Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) is a highly conserved regulator of many signaling networks whose loss or inactivation can lead to a variety of disease states. The multifaceted roles played by RKIP are enabled by an allosteric structure that is controlled through phosphorylation of RKIP and dynamics in the RKIP pocket loop. Perhaps the most striking feature of RKIP is that it can assume multiple functional states. Specifically, phosphorylation redirects RKIP from a state that binds and inhibits Raf-1 to a state that binds and inhibits GRK2. Recent evidence suggests the presence of a third functional state that facilitates RKIP phosphorylation. Here, we present a three-state model to explain the RKIP functional switch and discuss the role of the pocket loop in regulating RKIP activity.

Keywords: allostery, GRK2, NMR, protein kinase C, Raf, RKIP, structure

I. INTRODUCTION

Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) is a homeostatic regulator of the mammalian kinome and inhibits a number of key signaling networks including Raf/MAP kinase, β-adrenergic signaling, and NFκB signaling.1–3 As expected for a protein involved in so many pathways, modulating RKIP function results in a wide range of physiological effects. Depletion or inactivation of RKIP results in disruption of normal cellular stasis and can lead to chromosomal abnormalities,4 metastatic cancer,5–7 asthma,8 systemic inflammatory response syndrome,9 Alzheimer’s,10 and heart disease.2 Disruption of RKIP function has even been implicated as a colonization strategy for the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, resulting in apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells.11 How does RKIP, a 21-kDa protein, perform these diverse functions? As discussed below, multiple structural conformations of RKIP regulated through phosphorylation and allosteric interaction can explain much of this activity.

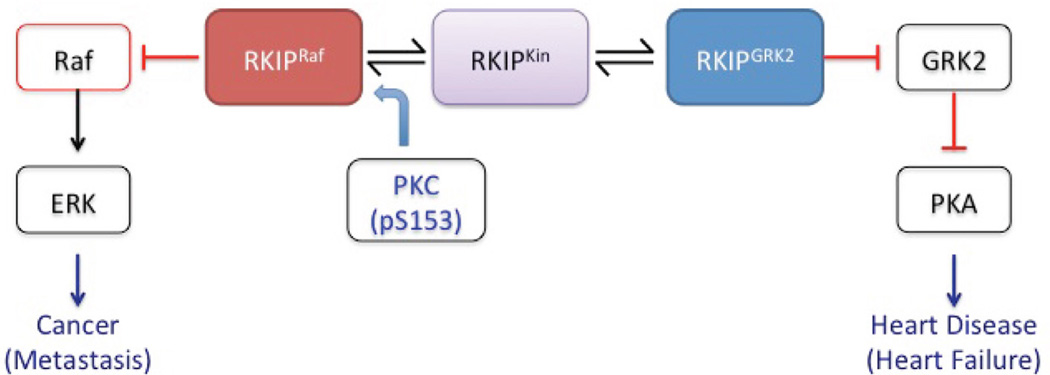

As an intermediary between multiple signaling networks, RKIP acts as both a kinase inhibitor and as a phosphorylation target. Among the pathways regulated by RKIP are those involving MAP kinase (MAPK) and the β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR). RKIP regulates these pathways by binding and inhibiting Raf and G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2), respectively.2 What makes these functions particularly interesting is that they are mutually exclusive: RKIP exists in at least two states, one capable of binding Raf and the other capable of binding GRK2. This functional switch is achieved via phosphorylation of S153 by protein kinase C (PKC; Fig. 1).2,12 How is the activation of the RKIP functional switch regulated? To explain this, we propose a three-state allosteric model for RKIP that is discussed in Section II.

FIG. 1.

Regulation of the RKIP Functional switch. Non-phosphorylated RKIP binds and inhibits Raf, effectively down-regulating ERK and thereby inhibiting metastasis. Phosphorylation of RKIP S153 by PKC switches RKIP function from Raf inhibition to GRK2 inhibition, effectively upregulating PKA, an important kinase involved in heart disease. We propose that PKC interacts with an intermediary state dubbed RKIPKin rather than with the RKIPRaf state directly.

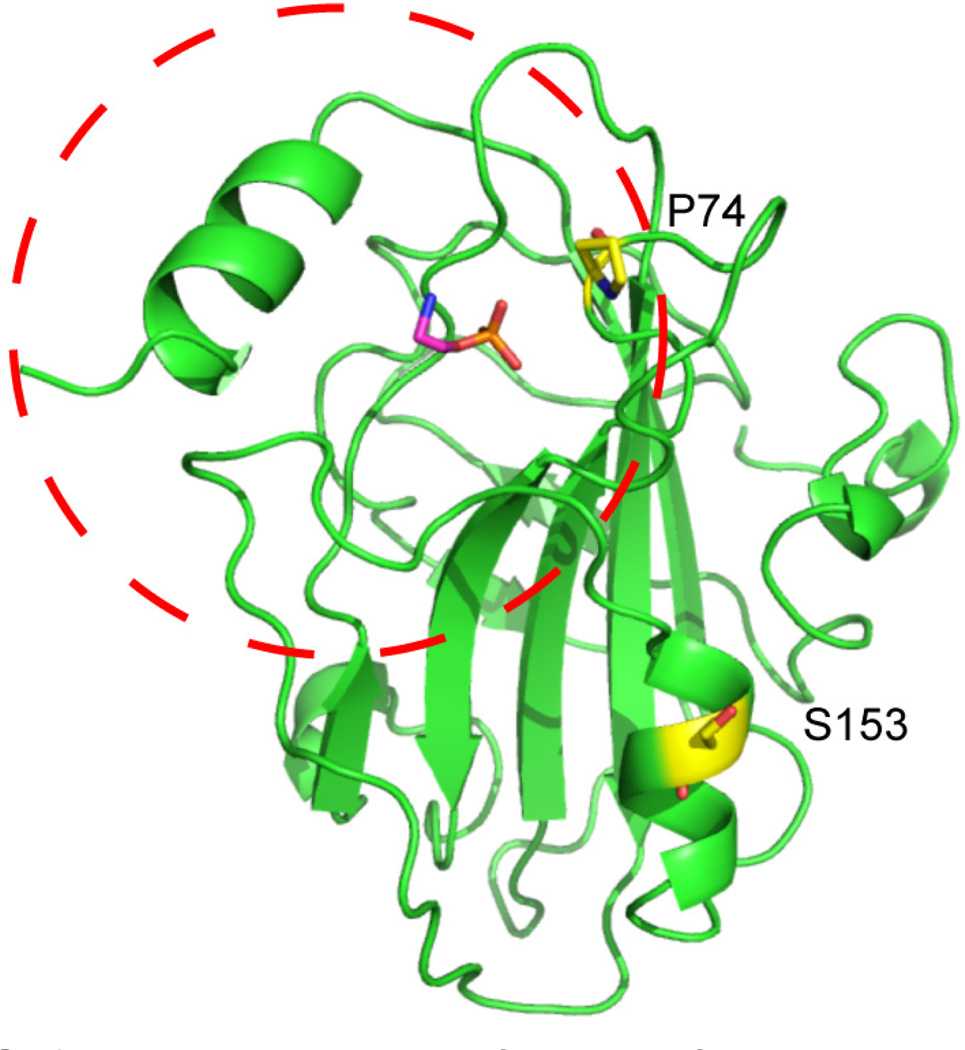

Recent evidence suggests that RKIP is a highly dynamic protein with a flexible pocket loop that potentiates the RKIP functional switch (Fig. 2).13 However, RKIP appears to function differently from other pocket proteins such as SH2-containing proteins. Many attempts have been made to identify physiological ligands that interact with the RKIP pocket, yet none have been shown to directly bind to RKIP. Our current understanding of ligand interactions with the RKIP pocket, and the potential role of ligand binding to the pocket in regulating RKIP function, is the topic of Section III.

FIG. 2.

Important structural features of RKIP. The RKIP binding pocket (circled) was originally implicated in binding PE. S153, the site of PKC phosphorylation, does not interact with the pocket loop directly. Nevertheless, the pocket loop mutant P74L exhibits additional loop dynamics and increased S153 phosphorylation.

II. A THREE-STATE MODEL FOR RKIP REGULATION

RKIP exists in multiple discrete states, which explains its ability to assume different functional roles. It is well established that phosphorylation of S153 converts RKIP from a state that binds Raf (RKIPRaf) to a state that binds GRK2 (RKIPGRK2).2 RKIPRaf has been crystallized from a number of species including bovine, rat, and human.13–15 By contrast, RKIPGRK2 has not yet been crystallized. A nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) based study illuminated some of the dynamics underlying RKIP functionality.13 This evidence suggests the existence of a third state that interacts with kinases that phosphorylate RKIP, which we now term RKIPKin. This three-state model provides a basis to explain RKIP function and dynamics (Fig. 1).

Evidence for the RKIPKin state is based on experiments involving the RKIP loop mutant P74L. Introducing the P74L mutation into the RKIP pocket loop potentiates the functional switch from Raf binding to GRK2 binding in cells relative to wild type (WT) RKIP.13 An equivalent mutation in tomato plants causes a developmental switch from shoot growth to flowering.16 It has been suggested that P74L induces the functional switch by altering the Raf binding interface.17 If this were true, then binding to GRK2 would not be dependent on phosphorylation of S153. However, combining P74L with a mutation at S153 that blocks phosphorylation rescues the original Raf-binding phenotype,13 demonstrating that the P74L mutant cannot switch function without S153 phosphorylation. Furthermore, the P74L mutant promotes kinase binding, enabling increased phosphorylation of RKIP.13 Thus, it appears that P74L promotes the functional switch by facilitating phosphorylation of S153, rather than causing RKIP to switch functions directly. Since residue P74 is distant from S153 (Fig. 2), it is unlikely that P74L is promoting PKC binding directly.

How might P74L promote phosphorylation? This process can be understood in terms of energy states. Proteins constantly sample conformations ranging from the ground states (observed by X-ray crystallography) to random coils. At equilibrium, each state is populated according to its free energy (ΔG). In some cases, ΔG can be affected by structural perturbations such as mutation or phosphorylation, and this appears to be the case for RKIP. The connection between P74 and S153 is not immediately obvious from the crystal structure because the two amino acids are not co-localized (Fig. 2). However, NMR analysis has shown that the pocket loop is more dynamic for P74L compared to WT.13 The increase in pocket flexibility is consistent with RKIP sampling one or more conformations that are not represented in the available crystal structures. We propose that a non-phosphorylated WT RKIP molecule spends most of its time in the RKIPRaf state. Due to random energy fluctuations, this molecule will occasionally sample less stable states (e.g., RKIPKin). During these rare stochastic excursions to the RKIPKin state, PKC is able to phosphorylate S153. In this model, the P74L mutation stabilizes the RKIPKin state relative to the RKIPRaf state, thereby leading to increased phosphorylation.

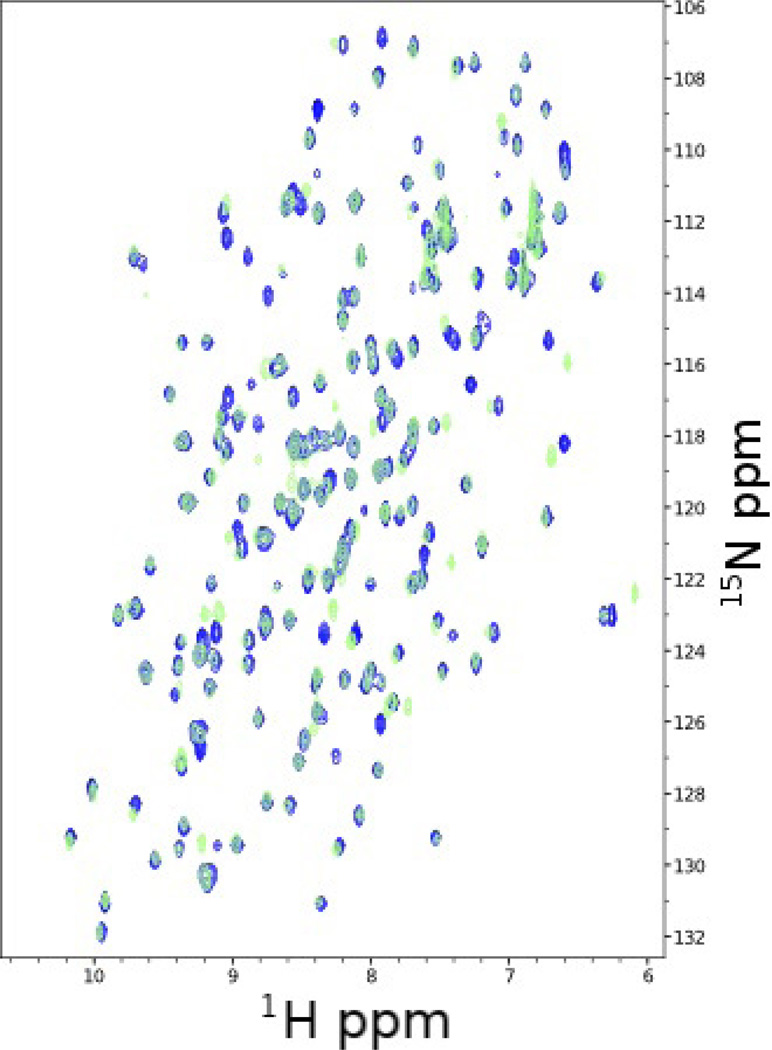

Direct evidence for the RKIPKin state comes from NMR chemical shift (peak position) analysis and relaxation dispersion measurements by Rosner and colleagues.13 The NMR spectra indicate that both WT and P74L predominately populate RKIPRaf, but P74L populates RKIPKin to a degree that is detectable by NMR (>0.5%). In 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra, each peak corresponds to an H-N pair arising from the backbone amides of non-Pro residues and NH containing side chains. Peak positions depend on the chemical environment and thus reflect backbone orientation and tertiary structure interactions. When a residue rapidly interconverts between multiple conformations with different chemical environments, the result is a peak position that is the population-weighted average of each state. Comparing the WT and P74L HSQC spectra reveals small but significant changes for multiple residues (Fig. 3),13 consistent with P74L sampling an alternative state. The fact that many of these residues are not in direct contact with P74 suggests that these shifts are due to conformational change rather than simply local changes in side chains around the mutated residue. Relaxation dispersion measurements, which reveal additional dynamics in the pocket loop region for the P74L RKIP mutant, provide independent evidence for a higher energy state.13 Together, these lines of evidence provide strong support for the existence of an intermediate high-energy state.

FIG. 3.

Residues perturbed by P74L. An HSQC overlay for WT (dark) and P74L (light) RKIP illustrates the small yet significant changes in chemical environment for residues in and around the pocket loop. Each peak corresponds to a hydrogen-nitrogen pair with known identity.

The existence of the RKIPKin state helps explain RKIP activity in cells. As noted above, phosphorylation of RKIP S153 causes a switch in function from Raf-1 inhibition to GRK2 inhibition (Fig. 1). Mutation of residue P74 to P74L significantly increases phosphorylation of this site by PKC,13 presumably due to an increase in the population of the kinase binding (high energy) state, RKIPKin. This observation is consistent with PKC phosphorylating the RKIPKin state rather than the RKIPRaf state. This result is not surprising given what is known about the RKIPRaf structure and kinase active sites. S153 is part of a stable helix in RKIPRaf. However, kinase active sites bind peptides in more dynamic coil-like conformations. Therefore, RKIP must adopt an alternative conformation with an unfolded helix prior to S153 phosphorylation. Although we do not yet know the structure of the RKIPKin state, we expect a partially or completely unfolded helix to be one of the structural properties of this state.

Factors that impact the RKIPKin state may play an important role in the physiological regulation of RKIP function. We expect stabilization of RKIPKin to facilitate the switch to RKIPGRK2 and destabilization to inhibit this transition. The stability of RKIPKin could be affected by phosphorylation, other posttranslational modifications, or ligand binding, allowing RKIP function to be affected by additional inputs. Thus, our three-state model enables more nuanced control of RKIP function than is possible for a two-state model. For example, in the absence of RKIPKin state stabilization by mutation or posttranslational modification, the ability of PKC to trigger the RKIP functional switch will be limited. Consistent with this idea is the observation that phosphorylation of GRK2 by PKC actually activates GRK2 by preventing calmodulin-induced inhibition,18 the opposite of what one would expect if the sole influence of PKC on GRK2 was to inhibit it via RKIP. Thus, in the absence of other signals that promote conversion of RKIPRaf to RKIPGRK2, PKC stimulation results in upregulation of GRK2. However, in the presence of an additional input that stabilizes RKIPKin, we expect PKC to phosphorylate RKIP sufficiently to induce the RKIP functional switch, resulting in downregulation of GRK2. We hypothesize that phosphorylation of RKIP by other kinases at different sites plays a role in controlling the stability RKIPKin state, a mechanism that would enable RKIP to both regulate and be regulated by the cellular kinome.

III. POCKET BINDING

In the three-state model described above, the RKIP pocket allows for allosteric regulation of functional switching. This role is in contrast to the function of ligand binding that has classically been associated with the RKIP pocket. Other than a potential interaction with a long chain phospholipid,8 there is no compelling evidence of a naturally occurring ligand that has a physiological effect by binding to the RKIP pocket. In this section, we will discuss these findings as well as other reported interactions with the RKIP pocket.

A. Raf-1 Binding to RKIP

Raf-1 is activated by phosphorylation of residues at serine 338 (S338) and tyrosine 341 (Y341) within the N terminus of the kinase domain.19 It has been suggested that Raf-1 binds to RKIP through an interaction between the RKIP pocket and phosphorylated Y341 in Raf-1 in a manner analogous to SH2 binding domains.20 This model predicts that ligands bound to the RKIP pocket should interfere with Raf-1 binding. However, our results based on cell and NMR studies are not consistent with this mechanism. In particular, small planar ligands that bind the RKIP pocket do not interfere with Raf-1 binding.21

Further evidence also argues against the SH2 pocket model to explain Raf interaction with RKIP. Although it is possible to force binding by flowing phosphotyrosine over pre-crystalized RKIP,22 NMR studies indicate that phosphotyrosine does not bind RKIP at physiological pH.21 Consistent with this finding is the observation that the RKIP pocket is not structurally homologous to SH2 domains, and it lacks the conserved arginine that SH2 domains use to bind phosphotyrosine.23 Similarly, a Raf-1 peptide fragment that includes phosphorylated S338/Y341 residues was reported to bind to RKIP better than the nonphosphorylated fragment,20 but we were unable to observe binding of either peptide to RKIP by NMR (Rosner and Jones, data not shown). RKIP overexpression also blocks phosphorylation of Raf-1 residues S338 and Y341 in cells,24 indicating that these residues do not need to be phosphorylated in order for RKIP to bind Raf-1. In summary, the evidence to date suggests that Raf-1 interacts with Raf-1 independently of tyrosine phosphorylation and does not require Raf-1 to penetrate into the pocket for binding to occur.

B. Phospholipid Binding

RKIP is a member of the highly conserved phospha-tidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) family, a family found throughout evolution even as far back as bacteria.25–27 As the name suggests, the identifying feature of the PEBP family is a highly conserved pocket originally thought to bind the phospholipid head group o-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE; Fig. 2). RKIP was first crystallized in the presence of PE (pH 4),14 but it was later shown that PE does not bind RKIP in solution at physiological pH.21 However, the addition of aliphatic chains to PE does result in RKIP binding.13 In vitro, the phospholipid DHPE interferes with Raf-1 binding,13 although the poor (mM) affinity21 may preclude binding in vivo where phospholipids are primarily sequestered in membranes. A more promising physiological candidate for binding to the pocket is PE-conjugated 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15HETE-PE), which was shown to decrease Raf-1 binding in ex vivo asthmatic epithelial cells.8 The generality of this phospholipid binding remains to be determined, but these results suggest that, at least under certain conditions, phospholipids can disrupt RKIP’s interaction with Raf-1. The observation that phospholipids can interfere with binding8,13 is consistent with a model whereby Raf-1 binds residues within the region of the pocket without penetrating into the pocket. Bulky ligand groups extending from the RKIP pocket could then disrupt the RKIP-Raf-1 interaction.

C. Locostatin and Other Small Molecules

The synthetic ligand Locostatin has been reported as an RKIP-specific inhibitor.28 Yet both its role as an RKIP inhibitor and its specificity for RKIP over other proteins remain questionable. NMR studies with a structurally similar Locostatin precursor have confirmed that binding is specific to the RKIP pocket.29 However, no interference with RKIP binding to Raf-1 was observed when the structurally similar precursor was tested.29 The difference in results may be attributed to the ability of Locostatin, but not its precursor, to covalently attach to His86 in the binding pocket.30 These results raise the possibility that covalent modification of RKIP by Locostatin disrupts RKIP structure, making RKIP nonfunctional rather than simply blocking the binding sites for Raf-1 and GRK2. Additionally, other studies revealed nonspecific toxicity of Locostatin that could readily cause deleterious effects in a variety of systems.29 Thus, caution is advised when interpreting studies employing Locostatin in terms of both mechanism and specificity.

Other small molecules reported to bind human RKIP include GTP and flavin mononucleotide (FMN).31 However, the physiological relevance and generality of these interactions are questionable given that they do not bind rat RKIP when analyzed by solution NMR.21 Furthermore, GTP and FMN binding to human RKIP was strongest in very low ionic conditions, and their affinities are greatly reduced in the presence of 100 mM salt,31 suggesting that binding may not occur under physiological conditions.

Although interactions with these or other small molecules in specific conditions cannot be ruled out, our cumulative studies suggest that the RKIP pocket is not generally used for ligand binding. The pocket may in fact be largely vestigial, having once acted as a ligand-binding pocket. Either way, the pocket might have remained in the PEBP family due to structural restraints such as interfacial requirements for protein-protein interaction or the need for an allosteric network connecting phosphorylation and binding sites.

IV. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In summary, RKIP is a highly dynamic protein capable of switching between different functions. Regulation of this functional switch can best be understood using a three-state model and involves allosteric connections under the control of the pocket loop. Although it has previously been suggested that the primary role of this pocket is ligand binding, current data suggest that the primary role of the RKIP pocket in mammalian cells is allosteric regulation of the functional switch.

RKIP is a fascinating, multifunctional protein likely to yield many new discoveries in the next few years. These will likely include the structural determination of the RKIPGRK2 and RKIPKin states and the conclusive identification of RKIP’s binding interfaces. Future studies will enable the development of ever more refined models connecting the regulation of RKIP’s many functions, extending beyond GRK2 and Raf-1. Understanding the molecular mechanism by which RKIP activities are regulated should lead to new therapeutic reagents for diseases such as cancer as well as alternative strategies for marshaling RKIP itself as a means of treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Casey Frankenberger for helpful comments. The work presented here was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. GM087630 (to M.R.R.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- GRK2

G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PKC

protein kinase C

- RKIP

Raf kinase inhibitory protein

- WT

wild type

REFERENCES

- 1.Yeung K, Seitz T, Li S, Janosch P, McFerran B, Kaiser C, Fee F, Katsanakis KD, Rose DW, Mischak H, Sedivy JM, Kolch W. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature. 1999;401:173–177. doi: 10.1038/43686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorenz K, Lohse MJ, Quitterer U. Protein kinase C switches the Raf kinase inhibitor from Raf-1 to GRK-2. Nature. 2003;426:574–579. doi: 10.1038/nature02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung KC, Rose DW, Dhillon AS, Yaros D, Gustafsson M, Chatterjee D, McFerran B, Wyche J, Kolch W, Sedivy JM. Raf kinase inhibitor protein interacts with NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and TAK1 and inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7207–7217. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7207-7217.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eves EM, Shapiro P, Naik K, Klein UR, Trakul N, Rosner MR. Raf kinase inhibitory protein regulates aurora B kinase and the spindle checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2006;23:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dangi-Garimella S, Yun J, Eves EM, Newman M, Erkeland SJ, Hammond SM, Minn AJ, Rosner MR. Raf kinase inhibitory protein suppresses a metastasis signalling cascade involving LIN28 and let-7. EMBO J. 2009;28:347–358. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun J, Frankenberger CA, Kuo WL, Boelens MC, Eves EM, Cheng N, Liang H, Li WH, Ishwaran H, Minn AJ, Rosner MR. Signalling pathway for RKIP and Let-7 regulates and predicts metastatic breast cancer. EMBO J. 2011;30:4500–4514. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu Z, Kitagawa Y, Shen R, Shah R, Mehra R, Rhodes D, Keller PJ, Mizokami A, Dunn R, Chinnaiyan AM, Yao Z, Keller ET. Metastasis suppressor gene Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) is a novel prognostic marker in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006;66:248–256. doi: 10.1002/pros.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, O’Donnell VB, Balzar S, St Croix CM, Trudeau JB, Wenzel SE. 15-Lipoxygenase 1 interacts with phosphatidyl-ethanolamine-binding protein to regulate MAPK signaling in human airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14246–14251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018075108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright KT, Vella AT. RKIP contributes to IFN-gamma synthesis by CD8+ T cells after serial TCR triggering in systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Immunol. 2013;191:708–716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okita K, Matsukawa N, Maki M, Nakazawa H, Katada E, Hattori M, Akatsu H, Borlongan CV, Ojika K. Analysis of DNA variations in promoter region of HCNP gene with Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moen EL, Wen S, Anwar T, Cross-Knorr S, Brilliant K, Birnbaum F, Rahaman S, Sedivy JM, Moss SF, Chatterjee D. Regulation of RKIP function by Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbit KC, Trakul N, Eves EM, Diaz B, Marshall M, Rosner MR. Activation of Raf-1 signaling by protein kinase C through a mechanism involving Raf kinase inhibitory protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13061–13068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granovsky AE, Clark MC, McElheny D, Heil G, Hong J, Liu X, Kim Y, Joachimiak G, Joachimiak A, Koide S, Rosner MR. Raf kinase inhibitory protein function is regulated via a flexible pocket and novel phosphorylation-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1306–1320. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01271-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serre L, Vallee B, Bureaud N, Schoentgen F, Zelwer C. Crystal structure of the phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein from bovine brain: a novel structural class of phospholipid-binding proteins. Structure. 1998;6:1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banfield MJ, Barker JJ, Perry AC, Brady RL. Function from structure? The crystal structure of human phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein suggests a role in membrane signal transduction. Structure. 1998;6:1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pnueli L, Carmel-Goren L, Hareven D, Gutfinger T, Alvarez J, Ganal M, Zamir D, Lifschitz E. The SELF-PRUNING gene of tomato regulates vegetative to reproductive switching of sympodial meristems and is the ortholog of CEN and TFL1. Development. 1998;125:1979–1989. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rath O, Park S, Tang HH, Banfield MJ, Brady RL, Lee YC, Dignam JD, Sedivy JM, Kolch W, Yeung KC. The RKIP (Raf-1 kinase inhibitor protein) conserved pocket binds to the phosphorylated N-region of Raf-1 and inhibits the Raf-1-mediated activated phosphorylation of MEK. Cell Signal. 2008;20:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krasel C, Dammeier S, Winstel R, Brockmann J, Mischak H, Lohse MJ. Phosphorylation of GRK2 by protein kinase C abolishes its inhibition by calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1911–1915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason CS, Springer CJ, Cooper RG, Superti-Furga G, Marshall CJ, Marais R. Serine and tyrosine phosphorylations cooperate in Raf-1, but not B-Raf activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:2137–2148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S, Rath O, Beach S, Xiang X, Kelly SM, Luo Z, Kolch W, Yeung KC. Regulation of RKIP binding to the N-region of the Raf-1 kinase. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6405–6412. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shemon AN, Heil GL, Granovsky AE, Clark MM, McElheny D, Chimon A, Rosner MR, Koide S. Characterization of the Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) binding pocket: NMR-based screening identifies small-molecule ligands. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simister PC, Burton NM, Brady RL. Phosphotyrosine recognition by Raf kinase inhibitor protein. For Immunopathol Dis Therap. 2011;2:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu BA, Shah E, Jablonowski K, Stergachis A, Engelmann B, Nash PD. The SH2 domain-containing proteins in 21 species establish the provenance and scope of phosphotyrosine signaling in eukaryotes. Sci Signaling. 2011;4:ra83. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trakul N, Menard RE, Schade GR, Qian Z, Rosner MR. Raf kinase inhibitory protein regulates Raf-1 but not B-Raf kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24931–24940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serre L, Pereira de Jesus K, Zelwer C, Bureaud N, Schoentgen F, Benedetti H. Crystal structures of YBHB and YBCL from Escherichia coli, two bacterial homologues to a Raf kinase inhibitor protein. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:617–634. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simister PC, Banfield MJ, Brady RL. The crystal structure of PEBP-2, a homologue of the PEBP/RKIP family. Acta Crystallogr D. 2002;58:1077–1080. doi: 10.1107/s090744490200522x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eulenburg G, Higman VA, Diehl A, Wilmanns M, Holton SJ. Structural and biochemical characterization of Rv2140c, a phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2936–2942. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu S, Mc Henry KT, Lane WS, Fenteany G. A chemical inhibitor reveals the role of Raf kinase inhibitor protein in cell migration. Chem Biol. 2005;12:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shemon AN, Eves EM, Clark MC, Heil G, Granovsky A, Zeng L, Imamoto A, Koide S, Rosner MR. Raf Kinase Inhibitory Protein protects cells against locostatin-mediated inhibition of migration. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beshir AB, Argueta CE, Menikarachchi LC, Gascon JA, Fenteany G. Locostatin disrupts association of Raf Kinase Inhibitor Protein with binding proteins by modifying a conserved histidine residue in the ligand-binding pocket. For Immunopathol Dis Therap. 2011;2:47–58. doi: 10.1615/forumimmundisther.v2.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tavel L, Jaquillard L, Karsisiotis AI, Saab F, Jouvensal L, Brans A, Delmas AF, Schoentgen F, Cadene M, Damblon C. Ligand binding study of human PEBP1/RKIP: interaction with nucleotides and Raf-1 peptides evidenced by NMR and mass spectrometry. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]