Abstract

Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping studies have been integral in identifying and understanding virulence mechanisms in the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. In this study, we interrogated a different phenotype by mapping sinefungin (SNF) resistance in the genetic cross between type 2 ME49-FUDRr and type 10 VAND-SNFr. The genetic map of this cross was generated by whole-genome sequencing of the progeny and subsequent identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) inherited from the parents. Based on this high-density genetic map, we were able to pinpoint the sinefungin resistance phenotype to one significant locus on chromosome IX. Within this locus, a single nonsynonymous SNP (nsSNP) resulting in an early stop codon in the TGVAND_290860 gene was identified, occurring only in the sinefungin-resistant progeny. Using CRISPR/CAS9, we were able to confirm that targeted disruption of TGVAND_290860 renders parasites sinefungin resistant. Because disruption of the SNR1 gene confers resistance, we also show that it can be used as a negative selectable marker to insert either a positive drug selection cassette or a heterologous reporter. These data demonstrate the power of combining classical genetic mapping, whole-genome sequencing, and CRISPR-mediated gene disruption for combined forward and reverse genetic strategies in T. gondii.

INTRODUCTION

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular parasite that infects a broad range of mammals and birds from around the world (1). The ubiquitous prevalence of the parasite is due to several aspects of the parasite's life cycle, including the ability to infect all mammalian nucleated cells, the ability to reside in intermediate hosts for long periods by forming dormant bradyzoite cysts, and the ability to produce millions of environmentally resistant oocysts shed from felids, the definitive host for T. gondii (1). Due to its high prevalence, humans are commonly exposed to the parasite through consumption of undercooked meat or ingestion of oocysts that contaminate food and water (2, 3). Infection by the parasite very rarely leads to complications in healthy individuals, but in individuals with compromised immune systems, the parasite can cause disease and even death if untreated (4). Due to concerted efforts to study this opportunistic pathogen, many new molecular biology techniques have been developed to interrogate the biology of the parasite and its interaction with the host (5, 6).

One powerful approach has been the use of forward genetics in Toxoplasma gondii. Within its intermediate hosts, such as the mouse, the parasite is haploid and divides by mitosis, whereas following development of enteric stages in felids, the parasite is shed as a spore-like stage that undergoes meiosis in the environment. Sexual recombination can generate recombinant genotypes when multiple T. gondii genotypes coinfect a felid. The ability to complete the life cycle in the laboratory has been utilized to create several genetic crosses that have yielded important insights into virulence mechanisms employed by the parasite to resist host immune responses (7, 8). To facilitate these crosses, each parent was made resistant to an individual drug so that recombinant progeny could be readily acquired with double drug selection.

The natural S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) analog sinefungin (SNF) has been used as a potent inhibitor of T. gondii growth for several decades (9), yet the target of the drug remains unknown. Sinefungin-resistant (SNFr) lines can be obtained by treating parasites with the mutagen N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), as described previously (10). SNFr was used in early genetic crosses between cloned lines of the type 3 CTG strain in studies that described the frequency of out-crossing and selfing among independently marked strains (11). Subsequently, SNFr strains have been useful in the generation of several genetic crosses, as they allow for drug selection of recombinant progeny (12–14). Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping has been used to map the basis of SNFr to chromosome IX (15), although the precise locus responsible has not been identified. A recently described cross between type 2 ME49-FUDRr and type 10 VAND-SNFr parental lines (type 2 × type 10 cross) used the parental strain VAND, which was resistant to sinefungin (39). Importantly, the genomes of the progeny of this cross were sequenced in order to generate a genetic map, which was constructed by identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) inherited from the parents (39).

To take advantage of this genome-wide information, we sought to map and identify the causal resistance mutation inherited in the SNFr progeny. SNFr was mapped to a single locus encoding a putative amino acid transporter. We then used the newly adapted CRISPR technology (16) to disrupt this gene in T. gondii and confirm its role in sinefungin resistance. Because disruption of the gene confers drug resistance, we show that it can be used as a negative selectable marker to make transgenic parasites, which suffer no loss of virulence in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite culture.

Toxoplasma gondii strains RH, CTG, and CTG-SNFr (13, 17), GT1 and GT1-SNFr (14), and VAND and VAND-SNFr and the progeny of the VAND-SNFr × ME49-FUDRr genetic cross (39) were maintained as tachyzoites in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), gentamicin, and glutamine, referred to as D10. For harvests, parasites were isolated from HFFs by force needle passage and filtering and subsequently counted on a hemacytometer.

Mapping of the SNFr phenotype in ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr progeny.

A total of 24 progeny were assessed for sinefungin resistance by growth in 3 × 10−7 M sinefungin propagated in T25 flask HFF cultures with D10. The progeny were coded based on no growth (score of 0; sinefunginn sensitive [SNFs]) and growth (score of 1; SNFr). A primary scan with a binary phenotype for SNFr was run in jQTL v1.3.4 with 1,000 permutations using the genetic map previously generated for the ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr cross (J. S. Shaik, A. Khan, S. M. Beverley, and L. D. Sibley, submitted for publication). The primary QTL on chromosome IX was used as an additive covariate and run in a secondary QTL scan.

Sequence reads for the progeny and parental strains from the ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr cross were deposited to the NCBI short-read archive and are available at the following link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/258152. To identify SNPs, Illumina reads for the 24 progeny were individually aligned to the VAND (SNF sensitive) (GenBank accession number AEYJ00000000.1) reference genome using CLCGenomics v7.0.3 with the following parameters: mismatch cost, 3; insertion cost, 3; deletion cost, 3; length fraction, 0.9; similarity fraction, 0.8; and global alignment. The Quality-Based Variant Detection tool in CLCGenomics was used to identify SNPs across all 14 chromosomes with a minimum coverage of 10. VAND scaffolds corresponding to the QTL peak on chromosome IX were identified and SNPs included in this region for all progeny were imported into Excel. To find any SNP(s) associated with SNFr, progeny were ordered by the SNFr phenotype, and SNPs in the QTL region were scanned to identify those that were present in SNFr progeny and absent in SNFs progeny (i.e., retaining the VAND-SNFs allele).

To determine copy number variation (CNV) of TGVAND_290860 in the progeny, Illumina reads of the progeny were aligned to the ME49 reference genome with Bowtie 2 v2.1.0 (18) using –end-to-end. The average number of reads per bp across 8,320 chromosomal based genes (Gene-Readavg) was determined using samtools mpileup (19). The baseline 1× value for each strain was obtained by calculating the average read per bp (1×mean) and standard deviation (1×stdev) across all bp within genes (as one set) in the second and third quartiles (4,160 genes) of the distribution of the 8,320 genes. The CNV for a gene was then determined where Gene-Readavg ≥ (1×mean + 3 × 1×stdev), and the CNV estimate is Gene-Readavg/1×mean. Plots were generated in R.

Sequencing of the target locus in SNFr strains.

Genomic lysates of parasite strains were prepared (proteinase K digestion at 37°C for 1 h followed by 2 h of incubation at 56°C and inactivation by incubation at 95°C for 15 min) and used as templates to PCR amplify the TGVAND_290860 region using set 1 primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in an iProof high-fidelity PCR (Bio-Rad). Amplified PCR products were sent to GeneWiz (South Plainfield, NJ) for sequencing of the whole coding sequence (CDS) using set 2 primers (see Table S1). Both wild-type (WT) and SNFr sequences for a given strain were aligned to the ME49 reference sequence using ContigExpress (Invitrogen), and SNPs unique to the SNFr strain were identified. In addition, an SNFs strain RH-based consensus sequence was generated from an alignment of the RH sequence reads to the ME49-based TGME49_290860 reference for use in verifying CRISPR-generated SNFr lines (see below).

CRISPR sgRNA plasmid construction.

CRISPR small guide RNA (sgRNA) plasmids targeting the TGVAND_290860 orthologue were constructed as previously described (16). Briefly, six sgRNA targets 20 bp long (sgRNA-C1 to -6) were identified in TGVAND_290860 (highlighted green in Table S1 in the supplemental material) upstream of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sites adjacent to locations 45, 437, 777, 1,166, 1,517, and 1,730 bp from the start of the CDS. These sgRNAs were incorporated into primers (see respective set 3 primers in Table S1) containing sequence priming off the CRISPR template pSAG1::CAS9-U6::sgRNA plasmid (Addgene plasmid 54467) and used to amplify the plasmid containing a new sgRNA target in Q5 Hot-Start high-fidelity PCRs (NEB). PCR products were then processed in Q5 site-directed mutagenesis KLD (NEB) reactions, plasmid clones were identified with restriction enzyme digestion, and sequences were verified. Plasmid containing sgRNA-C6, named pSAG1::CAS9-U6::sg290860-6, was deposited at Addgene, under principal investigator David Sibley, Plasmid 59855.

CRISPR-generated SNFr RH strain parasites.

RH strain parasites were harvested as described above and resuspended at 5 × 106 per 150 μl in Cytomix. A total of 7 μg of plasmid was combined with 150 μl of parasites and electroporated using a BTX Harvard Apparatus ECM 830 electroporator using the following mode: high voltage (HV), 1,700 V, and 174 μs. Electroporated parasites were allowed to grow for 2 days and selected with 3 × 10−7 M SNF. For each of the C1 to -6 electroporations, parasites began to grow out of SNF selection within 3 days. Parasites were subcloned to 96-well plates after an additional passage in SNF, and plaques were allowed to form for 9 days. Single clones or plaques were identified and expanded to create genomic lysates in order to sequence verify the CRISPR-targeted disruption of TGVAND_290860.

Sequencing of the target locus in CRISPR-generated SNFr clones.

To sequence verify the SNFr clones, genomics lysates for C1 to -6 SNFr clones were prepared and used as the template to amplify the TGVAND_290860 CDS using the set 4 primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in a Q5 high-fidelity PCR (NEB). Amplified PCR products were sent to GeneWiz and sequenced using the respective set 5 primers (see Table S1). The sequence was aligned to the SNFs RH consensus for TGVAND_290860, and differences (indels or large insertions) near the CRISPR target sequence were identified.

Plaque assay of SNFr parasites generated by CRISPR.

RH strain parasites were electroporated as described above, except with 3 × 106 parasites and 2 μg of either sgRNA-C6 or the sgRNA-UPRT negative-control plasmid. Parasites were inoculated onto HFF monolayers and allowed to expand for 2 days. The percentage of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive parasites was determined by examination on a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope (Zeiss). Parasites were then harvested, filtered, counted, and then passaged to 6-well plates at 1 × 105, 2 × 104, or 2 × 103 per well in selection with 3 × 10−7 M SNF. Plaques were allowed to form for 10 days, plates were then fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 0.05% crystal violet, and plaques were counted.

Plaque assay of SNFr parasites generated by CRISPR plus a DHFR* cassette.

The pyrimethamine selection fragment was amplified from a plasmid containing the pyrimethamine-resistant dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR*) resistance cassette using the set 6 primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in a Q5 high-fidelity PCR. RH strain parasites were electroporated as described above, except with 2 × 106 parasites, with 2 μg of either sgRNA-C6, sgRNA-C1, or the sgRNA-UPRT negative-control plasmid and 400 ng of purified DHFR* resistance cassette PCR product. Parasites were allowed to expand for 2 days and then passaged into new HFF monolayers with 10 μM pyrimethamine selection. After expansion in pyrimethamine, parasites were harvested as described above and inoculated into 6-well plates at 1 × 104 or 1 × 103 per well with selection with 3 × 10−7 M SNF. Plaques were allowed to form for 7 days; 6-well plates were then fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 0.05% crystal violet, and plaques were counted. Clones were obtained by limiting dilution into 96-well plates for both SNFr sgRNA-C6 and sgRNA-C1 samples, and 11 clones per sample type were screen for DHFR* integration using respective set 7 primers (see Table S1). The amplified S2/D1 band (see Fig. 5A and Table S1) for one sgRNA-C6 clone was sequenced at GeneWiz to confirm the integration at TGVAND_290860.

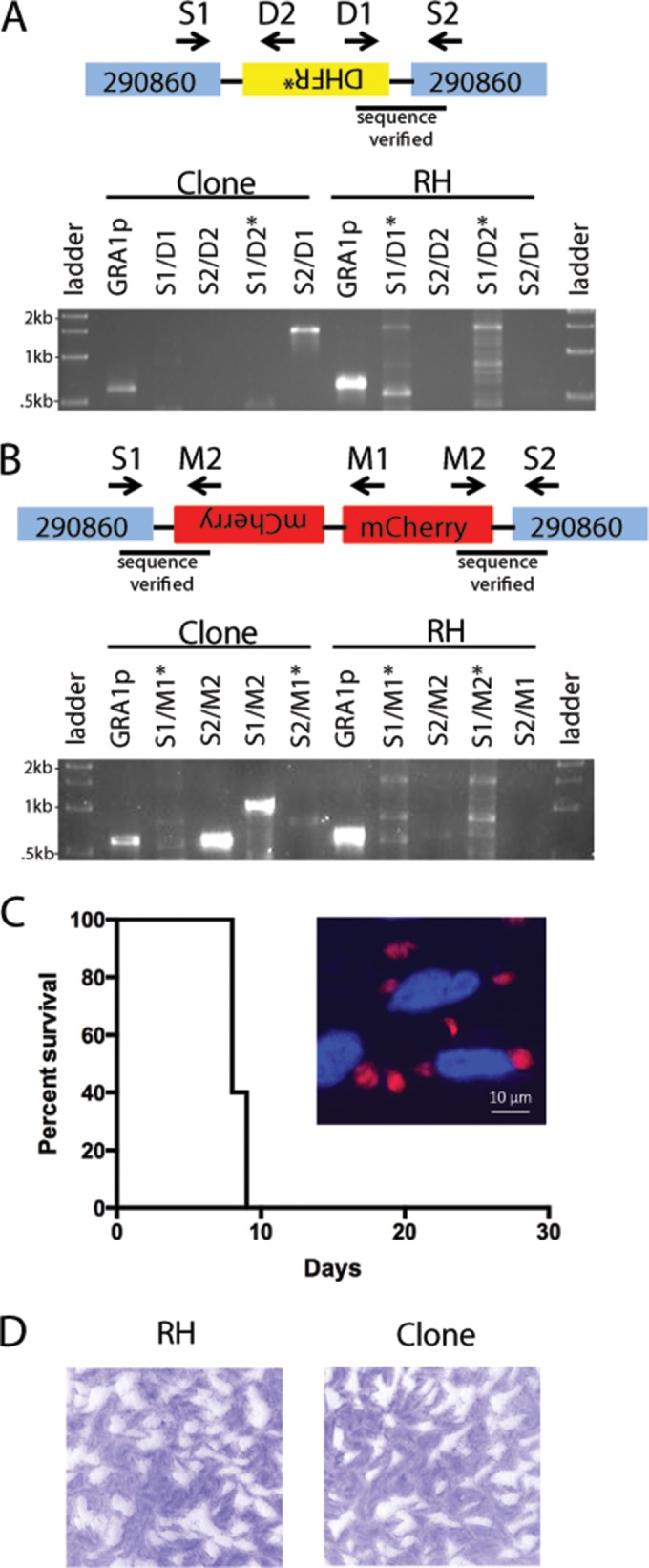

FIG 5.

Insertion of DHFR* and mCherry cassettes into the orthologue of TGVAND_290860 using SNF selection. (A and B) Diagram of DHFR* (A) and mCherry (B) integration into the TGVAND_290860 orthologue. PCR primers used are indicated with arrows in the diagram and above the top of the gel. Shown is an agarose gel separation of PCR products detecting integration in an SNFr clone or RH (negative control). GRA1p, Gra1 promoter/positive control for PCR. Asterisks mark lanes with unspecific bands. (C) Survival plot showing that disruption of TGVAND_290860 in the mCherry-positive SNFr clone does not affect virulence in CD-1 mice. Mice (n = 5) were inoculated with 1,000 tachyzoites i.p. The inset shows fluorescence of mCherry-positive parasites. Red, mCherry; blue, Hoechst-stained nuclei. (D) Representative plaques from a plaque assay of wild-type RH and an mCherry-positive SNFr clone.

Insertion of a GRA1P-mCherry-SAG13′ UTR cassette using CRISPR.

The GRA1p-mCherry-SAG3′ untranslated region (UTR) reporter was amplified from a plasmid containing the cassette using the set 8 primers (see Table S1) in a Q5 high-fidelity PCR. RH strain parasites were electroporated as described above, except with 3 × 106 parasites, 2 μg of sgRNA-C6 plasmid, and 400 ng of purified mCherry reporter cassette PCR product. Parasites were passaged to fresh HFF monolayers, allowed to expand for 2 days, and then grown with selection with 3 × 10−7 M SNF. Parasites were passaged to new HFF monolayers to expand and then 2 days later were cloned to 96-well plates. Plaques were allowed to form for 7 days, at which time parasite clones or plaques were identified. Wells with single plaques were screened for live mCherry fluorescence on a Zeiss microscope. An mCherry-positive clone was expanded, and lysates were made and used to verify the mCherry insertion into the TGVAND_290860 C6 locus using the set 9 primers (see Table S1) by PCR. Bands S1/M2 and S2/M2 (see Fig. 5B and Table S1) were sequenced, confirming the integration of mCherry at the TGVAND_290860 locus. Virulence of the mCherry-positive clone was assessed by intraperitoneally (i.p.) injecting 1 × 103 parasites into 5 CD-1 mice, after which mice were observed for survival. Plaque assays of wild-type RH and the mCherry-positive clone were conducted as described above, seeding either 500 or 1,000 parasites of each strain to 6-well plates, which were allowed to grow undisturbed for 7 days. The mean area of 30 plaques was measured for each strain in Photoshop, and a t test was performed in Excel.

RESULTS

Mapping of SNFr in the ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr cross.

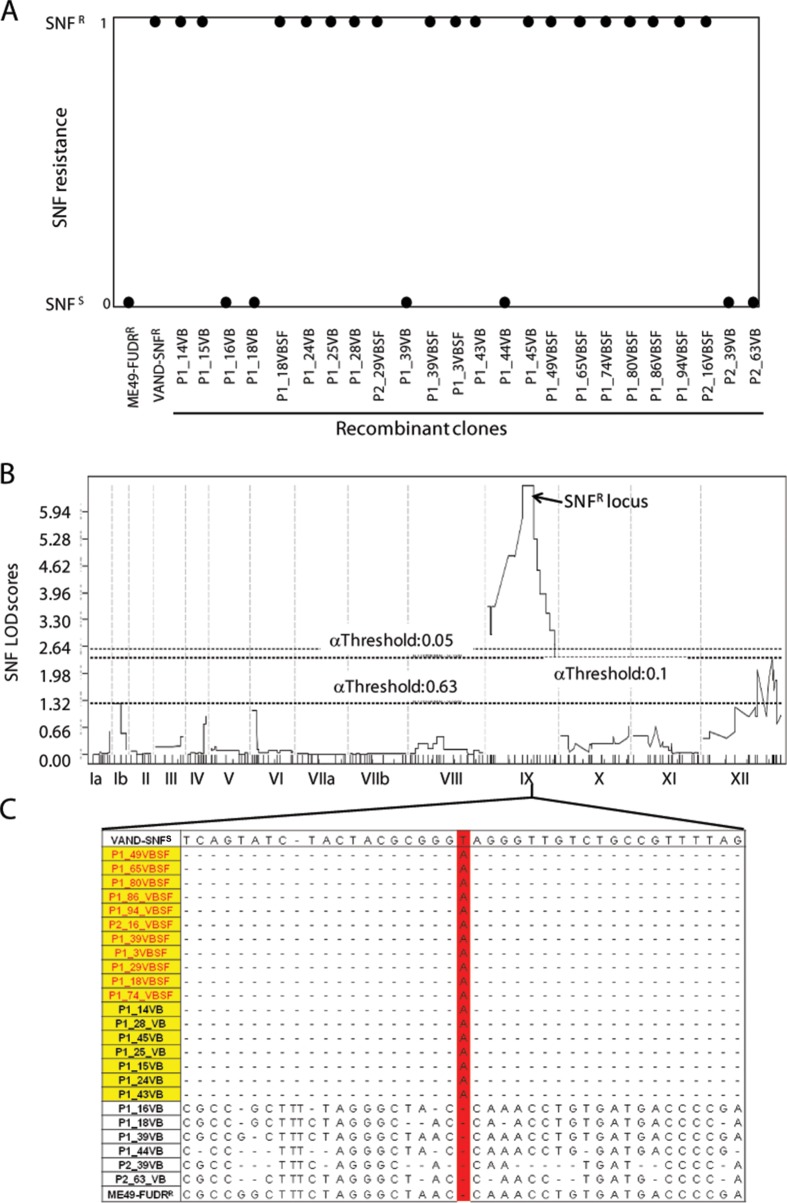

Although SNFr has previously been mapped to chromosome IX using a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)-based linkage map based on the type 1 GT1-FUDRr × type 3 CTG-SNFrARAr cross (17), the low resolution of this map has precluded identification of the responsible gene. Sinefungin resistance was assessed in 24 of the progeny from the newly conducted ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr cross. All 11 doubly drug (5-fluorodeoxyuridine [FUDR] and SNF) (39)-selected progeny (name ending in “SF”) were SNFr, whereas 7 of 13 unselected progeny (name ending in “VB”) were SNFs (Fig. 1A). The SNFr phenotype was mapped in jQTL as a binary distribution using the ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr genetic map generated previously (39). The primary scan generated one significant peak with a log of odds ratio (LOD) score of 6.57 on chromosome IX between markers MV358 and MV365, corresponding to ME49 region IX:3187822-4202044 (Fig. 1B). A secondary scan of the SNFr phenotype with the locus on IX used as a covariate failed to generate additional significant peaks (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Sinefungin resistance phenotype in the parents and progeny of the ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr cross. (A) Cloned progeny were grown in the presence of 3 × 10−7 M SNF and assessed for the ability to grown in the presence of drug. All doubly drug-selected progeny (VBSF) and 7 of 13 non-drug-selected progeny were SNF resistant. Phenotypes are shown as a binary trait where SNFr is scored as 1 and SNFs is scored as 0. (B) QTL mapping of the SNF resistance phenotype produced a significant peak in the middle of chromosome IX with a LOD score of 6.57. Confidence thresholds based on 1,000 random permutations of the data are shown. (C) Genomic reads for the progeny were aligned to the VAND-SNFs reference genome, and SNPs were identified. The region on IX spanning the QTL peak was assessed for SNPs present in SNF-resistant progeny (yellow) and not present in the SNF-sensitive progeny. Doubly drug-resistant progeny are shown in red lettering. One SNP matching this pattern (highlighted in red) was found at position 3901106 on chromosome IX. A small region containing SNF locus SNPs surrounding the T → A mutation is shown.

Because the VAND-SNFr parental strain was isolated following treatment with the mutagen ENU, we reasoned that resistance in the parent may have arisen from a mutation that would have been inherited in the SNFr progeny. We took advantage of the genomic assembly that exists for VAND that was sequenced from a sinefungin-sensitive (SNFs) strain (GenBank accession number AEYJ00000000.1). The genomic reads for each of the 24 progeny were aligned to the VAND-SNFs genome, and SNPs were identified within the QTL for SNFr. Importantly, all SNFr progeny inherited the SNF locus from VAND, whereas the SNFs strains inherited this region from the ME49-FUDRr parent (Fig. 1C). The genomic sequences within the QTL were scanned for SNPs common to all SNFr progeny and absent from SNFs progeny. Only one SNP meeting this criterion was found, a T → A substitution located at IX:3901106, or bp 1731 in the CDS of TGVAND_290860, resulting in an early stop codon in this gene (Fig. 1C and 2). This SNP pattern matched the SNFr phenotype in the progeny exactly, which is reflected in the estimate that the SNF locus on IX accounts for 100% of the phenotype effect size. To verify the presence of this SNP, the TGVAND_290860 gene was amplified and Sanger sequenced from genomic lysate of the VAND SNFs and VAND SNFr parents, the P1_16VB SNFs progeny, and the P1_49VBSF SNFr progeny. Only the VAND SNFr parent and P1_49VBSF SNFr progeny had the T → A mutation resulting in the early stop, C577# (Fig. 2).

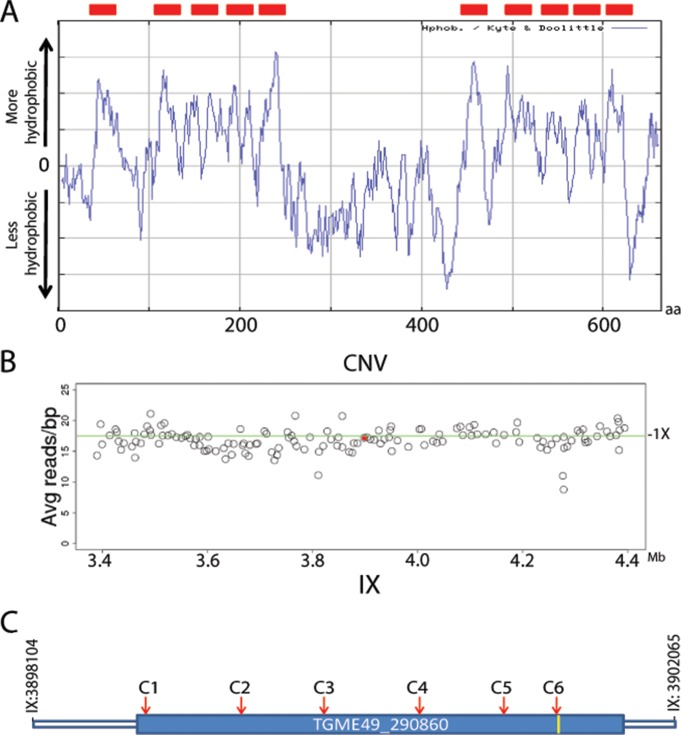

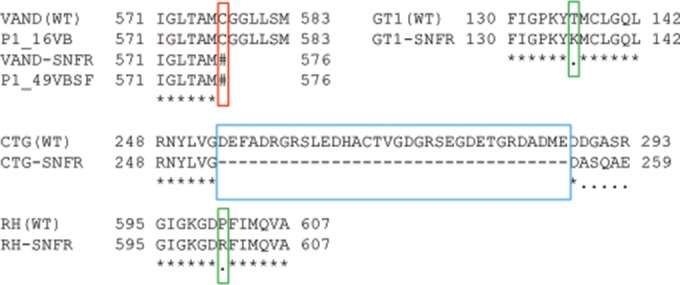

FIG 2.

SNFr results in alterations in the coding sequence of TGVAND_290860. The T → A SNP in the SNF-resistant progeny results in an early stop codon in the predicted amino acid transporter gene, TGVAND_290860 (red box). VAND and P1_16VB are SNFs, and VAND-SNFr and P1_49VBSF are SNFr. The TGVAND_290860 gene was sequenced from additional SNF-resistant strains and found to have either conservative amino acid residue changes in the GT1-SNFr and RH-SNFr lines compared to the wild type (WT) (green boxes) or a large deletion in CTG-SNFr (blue box).

Other crosses have used SNFr parents, notably a type 1 × type 3 cross, which used a type 3 CTG-SNFrARAr strain (13), and a type 1 × type 2 cross, which used a type 1 GT1-SNFr strain (14). To see if these SNFr strains also contained mutations in the orthologous genes in these backgrounds, the corresponding CDS was amplified and sequenced from both SNFs and SNFr lines of these strains. Indeed, the GT1-SNFr strain contained a single nonsynonymous SNP resulting in a threonine-to-lysine residue change, T136K, and there was a large deletion in the CTG-SNFr strain, resulting in the loss of 34 amino acids, and then a frameshift and an early stop (Fig. 2). Collectively, these data support the conclusion that alterations in TGVAND_290860, or its orthologues in other strains, result in sinefungin resistance.

TGVAND_290860 is predicted to encode an amino acid transporter.

TGVAND_290860 is a single exon gene of 664 amino acids in length that is predicted to encode an amino acid transporter (20). In support of this annotation, TGVAND_290860 is predicted to contain 10 transmembrane domains (Fig. 3A), peptides matching the center region of the orthologous protein have been isolated from the membrane fraction of the type 1 RH strain parasite by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (20, 21), and mRNA sequencing (mRNA-Seq) data show read coverage that spans the full length of the predicted mRNA (http://ToxoDB.org). Various membrane-bound transporters have been identified as drug resistance genes in Plasmodium parasites, and in some cases increases in copy number variation (CNV) of these transporters were associated with drug resistance (22, 23). Given this prior pattern, we determined whether the predicted transporter TGVAND_290860, and all the other genes within the SNF locus, had CNV in the progeny of the type 2 × type 10 cross. CNV estimates for TGVAND_290860 in the 24 progeny were all very near the 1× copy number mean for the genome, as shown for the P1_49VBSF SNFr progeny (Fig. 3B). In addition, all genes within the SNF locus were not amplified for all progeny, ruling out CNV as a potential driver of SNFr.

FIG 3.

TGVAND_290860 predicted annotation and CNV. (A) A hydrophobicity plot indicates 10 hydrophobic regions, suggesting that TGVAND_290860 encodes a transmembrane protein (red boxes). aa, amino acids. (B) Genomic reads of the progeny were aligned to the ME49 reference genome, and the average read per gene was determined. In all parents and progeny, TGVAND_290860 was found to exist as a single copy. The plot shows average read per bp of genes 500 kb on either side of TGVAND_290860 (indicated by the red dot); the green line shows the 1× average for the genome. (C) Diagram of TGVAND_290860, which consists of a single exon gene that is predicted to encode an amino acid transporter (location of T → A early stop, yellow bar). The location of CRIPSR single guide RNAs is shown by the positions of C1 to C6 (red arrows).

CRISPR disruption of TGVAND_290860 results in SNFr.

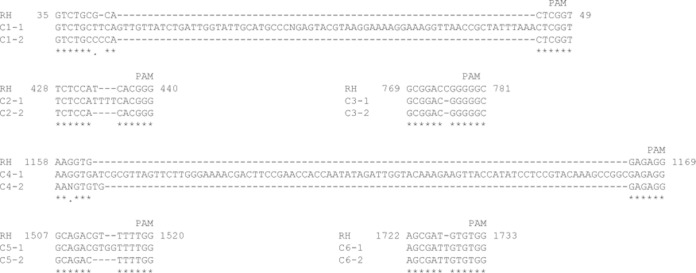

To confirm that disruption of TGVAND_290860 results in SNFr, we used the CRISPR-based technology recently adapted to T. gondii (16). A total of six small guide RNA (sgRNA) target sites, C1 to C6, were chosen that were relatively evenly spaced across TGVAND_290860 (Fig. 3C), with the last sgRNA, C6, having the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) motif starting at the T → A mutation seen at bp 1731 of the TGVAND_290860 CDS in the SNFr progeny (Fig. 4). CRISPR constructs containing the sgRNAs targeting the TGVAND_290860 orthologue were individually electroporated into RH strain parasites. After SNF treatment, the parasites with the C1 to C6 electroporations quickly recovered and expanded within 3 to 4 days. When parasites were electroporated with a negative-control sgRNA targeting the uracil phosphoribosyl transferase (UPRT) gene, they either never recovered (two samples) or slowly grew out of SNF selection after more than a week (one sample), presumably due to spontaneous mutations that confer resistance. To examine the basis of resistance, parasites from the SNFr sgRNA-UPRT population were cloned, and the orthologue of the TGVAND_290860 gene was sequenced from one clone; it was found to have a single SNP resulting in a P561R residue change (Fig. 2). Although not directly demonstrated, this alteration might be the basis for SNFr of this spontaneous mutant.

FIG 4.

Disruption of TGVAND_290860 in RH using CRISPR. SNFr parasites were created using the six CRISPR constructs. Two clones from each resistant pool were sequenced at the respective target site. The sequence from around the guide RNA is shown for the RH wild type and clones from C1 to C6, as indicated. Clones exhibited small indels or large insertions. PAM, protospacer adjacent motif. Numbering refers to the bp position in the TGVAND_290860 CDS.

To verify that the CRISPR constructs were disrupting the TGVAND_290860 orthologue, the C1 to C6 SNFr parasites were cloned and the sgRNA target regions were sequenced from two clones for each of the targeted regions. In each case, there was a disruption just upstream of the PAM anchoring the sgRNA (Fig. 4). Many CRISPR-disrupted SNFr clones contained small indels resulting in frameshifts. Two clones, C1-1 and C4-1, had insertions of 68 and 87 bp, respectively (Fig. 4). These results show that the TGVAND_290860 orthologue can be disrupted along the length of the gene to render parasites sinefungin resistant.

The efficiency of obtaining SNFr parasites using CRISPR to target the TGVAND_290860 orthologue by disruption was determined by plaque assay. RH parasites electroporated with either the sgRNA-C6 or the sgRNA-UPRT negative-control plasmid were seeded into 6-well plates and selected with SNF. Plaques were observed after SNF selection in all wells seeded with sgRNA-C6-containing parasites, whereas no plaques were observed in wells containing parasites with the sgRNA-UPRT negative control. When taking into account the transfection efficiency, the average efficiency of obtaining SNFr parasites by disrupting the TGVAND_290860 orthologue across two experiments was 5% (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Plaque assay of CRISPR-transfected parasites

| sgRNA | Expt | % GFP-positive parasites | No. of SNFr plaques at indicated no. of parasites/well |

% efficiency of SNFr at indicated no. of parasites/wella |

Avg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 105 | 2 × 104 | 2 × 103 | 1 × 105 | 2 × 104 | 2 × 103 | ||||

| sgRNA-C6 | 1 | 13.7 | 301 | 58 | 19 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 6.9 | 3.7 |

| 2 | 11.6 | 587 | 61 | 26 | 5 | 2.6 | 11.2 | 6.2 | |

| sgRNA-UPRT | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 9.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Calculated as no. of plaques/(no. of seeded parasites × percent GFP positive).

Use of SNFr as a negative selectable marker.

The ability to target TGVAND_290860 and render parasites SNFr opened the possibility of using this locus as a negative selectable marker in T. gondii. Although we were able to obtain SNFr parasites with all six CRISPR constructs to disrupt the gene, we were interested in assessing the efficiency of inserting a cassette into the TGVAND_290860 orthologue. We chose to cotransfect sgRNA-C6, sgRNA-C1, or the sgRNA-UPRT negative-control plasmid with PCR amplification of the pyrimethamine-resistant DHFR (DHFR*) drug selection cassette (24). Parasites were first selected with pyrimethamine, then seeded into 6-well plates, and selected with SNF in a plaque assay. Plaques were seen only in wells receiving a CRISPR plasmid targeting the TGVAND_290860 orthologue. The average efficiency of using disruption of the TGVAND_290860 orthologue as a negative selectable marker was 8.9% using sgRNA-C6 and 6.4% using sgRNA-C1 (Table 2). To verify integration of the DHFR* cassette into the TGVAND_290860 orthologue, 11 clones for each of the SNFr sgRNA-C6 and sgRNA-C1 samples were PCR screened; 9/11 (82%) and 7/11 (64%) clones, respectively, were positive for integration on at least one side of the sgRNA target (Table 2). For example, one sgRNA-C6 clone was positive for an integration of DHFR* on one side of the cut TGVAND_290860 target, where one band, S2/D1, of the expected size of approximately 1,500 bp was amplified (Fig. 5A). This band was sequenced, which confirmed the integration of the DHFR* cassette into TGVAND_290860 in the orientation shown in Fig. 5A.

TABLE 2.

Plaque assay of CRISPR-transfected parasitesa

| sgRNA | No. of SNFr plaques at indicated no. of parasites/well |

% SNFrb | No. of integrants/no. of clones tested | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 104 | 1 × 103 | |||

| sgRNA-C6 | Lysed | 89 | 8.9 | 9/11 |

| sgRNA-C1 | Lysed | 64 | 6.4 | 7/11 |

| sgRNA-UPRT | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

A DHFR* selection cassette was used in all cases.

Calculated as no. of plaques/no. of seeded parasites.

To extend the possibilities of utilizing TGVAND_290860 disruption as a means of making transgenic parasites, a cassette containing mCherry was used as a heterologous reporter. RH strain parasites cotransfected with sgRNA-C6 and a PCR amplicon consisting of the GRA1p-mCherry-SAG1_3′ UTR cassette lacking sequences homologous to the TGVAND_290860 orthologue were selected with SNF. Clones were obtained after SNF selection and screened for live mCherry fluorescence. From two independent transfections, 1/37 and 1/56 parasite clones were mCherry positive. Integration was verified by PCR in one of the mCherry-positive clones. Bands of the expected size were seen for two primers sets, S1/M2 at approximately 1,050 bp in size and S2/M2 at approximately 600 bp in size, suggesting that the clone contains at least two copies of the mCherry cassette (Fig. 5B). Both bands were sequenced to confirm the integration of mCherry in orientation shown in Fig. 5B. When examined by microscopy, a bright mCherry signal was detected diffusely in the parasite cytosol (Fig. 5C). To ensure that the integration of the reporter did not affect parasite viability, the mCherry-positive SNFr clone was tested in mice, and it showed no loss of acute virulence (Fig. 5C). Also, there was no difference in the in vitro growth of the SNFr clone compared to that of the WT parasites as determined by plaque assay (Fig. 5D).

DISCUSSION

We have combined the power of forward genetics and genome-wide sequencing to identify the gene responsible for SNFr in T. gondii. With the advent of affordable high-throughput sequencing, progeny of crosses can now be fully sequenced in order to generate a genetic map for use in forward genetic studies. Although SNFr had been previously mapped to a significant locus in the type 1 GT1-FUDRr × type 3 CTG-SNFrARAr cross (17), it was not until the whole-genome-sequencing based genetic map of the ME49-FUDRr × VAND-SNFr cross (39) was generated that identification of the causal SNFr mutation became tractable. Having identified the gene responsible, we further showed that disruption of this locus can be used for expression of heterologous genes using a negative selection strategy.

An additional technology that was critical to completing this study was the adaption of CRISPR to T. gondii (16, 25). Early attempts to disrupt the orthologue of TGVAND_290860 in the RHΔku80 parasite (26), either by gene knockout or by truncation, were unsuccessful. The RHΔku80 parasite is deficient in nonhomologous DNA end joining, and consequently, it integrates DNA using homologous recombination as the default repair pathway. This should have allowed us to target the TGVAND_290860 orthologue for disruption, but we were unable to obtain a knockout or an allelic replacement with the SNFr allele from the VAND strain after selection with SNF (data not shown). We are not certain why this approach was refractory to targeting the TGVAND_290860 orthologue, but this may result from the low efficiency of homologous integration. On the other hand, we were readily able to disrupt TGVAND_290860 at various points along the length of the gene using CRISPR technology. The combination of specificity provided by the sgRNA targeting TGVAND_290860 and subsequent DNA cleavage just upstream of the PAM sequence by CAS9 allowed us to easily obtain SNFr parasites, thus confirming that TGVAND_290860 is the SNF resistance gene mapped in the type 2 × type 10 cross. Based on these criteria, we have renamed the locus SNR1, for the gene encoding sinefungin resistance.

Targeted disruption of SNR1 results in SNF resistance, making it suitable for use in negative-selection strategies, thus increasing the tool kit available for reverse genetic studies with T. gondii. Disruption of SNR1 can be used as a negative-selection marker both with a drug selection cassette (DHFR*) and as a neutral locus for expression of heterologous reporters such as mCherry. Rendering parasites SNFr by targeting SNR1 has no effect on the parasites' ability to grow or cause disease in the mouse model, as is also the case with virulent GT1-SNFr (14) and VAND-SNFr (39) parental lines used to generate crosses. In addition, studies using SNFr parental lines to generate genetic crosses demonstrate that the SNFr lines were developmentally competent, as they produced viable in vivo-derived bradyzoite cysts which were able to complete the life cycle by producing recombinant oocysts in cats. For these reasons, disruption of SNR1 to confer sinefungin resistance should be a useful complement to the widely used negative selection strategy based on disruption of the uracil phosphoribosyl transferase (UPRT) locus using FUDR (27). For instance, to make transgenic parasites with two different expression cassettes, both FUDR and SNF could be employed to target cassette integration at UPRT and SNR1, respectively. Additionally the high efficiency of CRISPR for gene targeting will allow future studies to make use of gene disruption to render parasites resistant to FUDR (UPRT gene), adenine arabinoside (adenosine kinase [AK] gene) (28), or SNF (SNR1 gene). This strategy will allow efficient tagging of strains without the use of ENU, which introduces many other mutations into the genome.

In addition to T. gondii, there are other parasites that are sensitive to SNF from which resistance has been demonstrated. For example, Leishmania was found to be sensitive to sinefungin (29), resistant lines were eventually obtained (30), and it was shown that the sinefungin uptake system was the same as that used for AdoMet (31) based on a transporter called AdoMet1 (32). TGVAND_290860 and AdoMet1 are both membrane transporters responsible for SNFr, yet they share little sequence similarity. However, by analogy to the Leishmania system, it seems likely that TGVAND_290860 functions as a transporter of sinefungin and that its disruption confers resistance due to loss of uptake. This hypothesis could be tested by examining the various SNFr mutants created in this study to determine if they influence transcription, translation, protein stability, location, or transport functions. Trypanosomes are also sensitive to sinefungin (33), and although sinefungin can inhibit the uptake of AdoMet in Trypanosoma brucei (34), the transporter responsible for this is unknown. Similarly, sinefungin-resistant lines have been made in Plasmodium falciparum (35), but the gene responsible for resistance remains unidentified. With the advent of CRISPR technology in Plasmodium (36–38), transporters with homology to either the Leishmania AdoMet1 (32) or T. gondii SNR1 genes can be disrupted and tested for whether they confer SNFr, possibly providing a useful selectable marker.

Our studies demonstrate the power of combining classical genetic mapping, whole-genome sequencing, and CRISPR-mediated gene disruption for combined forward and reverse genetic strategies in T. gondii. This combination of strategies should allow mapping of complex phenotypes to specific mutations or SNPs and rapid assessment of the biological phenotypes they control by targeted mutation and or disruption.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jon P. Boyle for fruitful discussion, Nathaniel G. Jones for the plasmid containing the GRA1p-mCherry-SAG3′ UTR cassette, and ToxoDB.org for providing an adaptable genomics resource for the Toxoplasma gondii genome.

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant AI059176.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00229-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dubey JP. 2010. Toxoplasmosis of animals and humans. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JL, Dubey JP. 2010. Waterborne toxoplasmosis—recent developments. Exp Parasitol 124:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones JL, Dubey JP. 2012. Foodborne toxoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 55:845–851. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. 2004. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 363:1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roos DS, Donald RGK, Morrissette NS, Moulton AL. 1994. Molecular tools for genetic dissection of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Methods Cell Biol 45:28–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Striepen B, Soldati D. 2007. Genetic manipulation of Toxoplasma gondii, p 391–418. In Weiss LM, Kim K (ed), Toxoplasma gondii, the model apicomplexan: perspectives and methods. Academic Press, Elsevier, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibley LD. 2009. Development of forward genetics in Toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol 39:915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter CA, Sibley LD. 2012. Modulation of innate immunity by Toxoplasma gondii virulence effectors. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:766–778. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfefferkorn ER, Kasper LH. 1983. Toxoplasma gondii: genetic crosses reveal phenotypic suppression of hydroxyurea resistance by fluorodeoxyuridine resistance. Exp Parasitol 55:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(83)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfefferkorn ER, Pfefferkorn LC. 1979. Quantitative studies of the mutagenesis of Toxoplasma gondii. J Parasitol 65:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfefferkorn ER, Kasper LH. 1983. Toxoplasma gondii: genetic crosses reveal phenotypic suppression of hydroxyurea resistance by fluorodeoxyuridine resistance. Exp Parasitol 55:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(83)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sibley LD, LeBlanc AJ, Pfefferkorn ER, Boothroyd JC. 1992. Generation of a restriction fragment length polymorphism linkage map for Toxoplasma gondii. Genetics 132:1003–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su C, Howe DK, Dubey JP, Ajioka JW, Sibley LD. 2002. Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling acute virulence in Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:10753–10758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172117099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behnke MS, Khan A, Wootton JC, Dubey JP, Tang K, Sibley LD. 2011. Virulence differences in Toxoplasma mediated by amplification of a family of polymorphic pseudokinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:9631–9636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015338108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan A, Taylor S, Su C, Mackey AJ, Boyle J, Cole RH, Glover D, Tang K, Paulsen I, Berriman M, Boothroyd JC, Pfefferkorn ER, Dubey JP, Roos DS, Ajioka JW, Wootton JC, Sibley LD. 2005. Composite genome map and recombination parameters derived from three archetypal lineages of Toxoplasma gondii. Nucleic Acids Res 33:2980–2992. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen B, Brown KM, Lee TD, Sibley LD. 2014. Efficient gene disruption in diverse strains of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/CAS9. mBio 5:e01114-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01114-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan A, Taylor S, Su C, Mackey AJ, Boyle J, Cole R, Glover D, Tang K, Paulsen IT, Berriman M, Boothroyd JC, Pfefferkorn ER, Dubey JP, Ajioka JW, Roos DS, Wootton JC, Sibley LD. 2005. Composite genome map and recombination parameters derived from three archetypal lineages of Toxoplasma gondii. Nucleic Acids Res 33:2980–2992. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajria B, Bahl A, Brestelli J, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gao X, Heiges M, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Mackey AJ, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Wang H, Brunk BP. 2008. ToxoDB: an integrated Toxoplasma gondii database resource. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D553–D556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dybas JM, Madrid-Aliste CJ, Che FY, Nieves E, Rykunov D, Angeletti RH, Weiss LM, Kim K, Fiser A. 2008. Computational analysis and experimental validation of gene predictions in Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS One 3:e3899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price RN, Cassar C, Brockman A, Duraisingh M, van Vugt M, White NJ, Nosten F, Krishna S. 1999. The pfmdr1 gene is associated with a multidrug-resistant phenotype in Plasmodium falciparum from the western border of Thailand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:2943–2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rottmann M, McNamara C, Yeung BK, Lee MC, Zou B, Russell B, Seitz P, Plouffe DM, Dharia NV, Tan J, Cohen SB, Spencer KR, Gonzalez-Paez GE, Lakshminarayana SB, Goh A, Suwanarusk R, Jegla T, Schmitt EK, Beck HP, Brun R, Nosten F, Renia L, Dartois V, Keller TH, Fidock DA, Winzeler EA, Diagana TT. 2010. Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science 329:1175–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.1193225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donald RG, Roos DS. 1993. Stable molecular transformation of Toxoplasma gondii: a selectable dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase marker based on drug-resistance mutations in malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:11703–11707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sidik SM, Hackett CG, Tran F, Westwood NJ, Lourido S. 2014. Efficient genome engineering of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS One 9:e100450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huynh MH, Carruthers VB. 2009. Tagging of endogenous genes in a Toxoplasma gondii strain lacking Ku80. Eukaryot Cell 8:530–539. doi: 10.1128/EC.00358-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donald RG, Roos DS. 1995. Insertional mutagenesis and marker rescue in a protozoan parasite: cloning of the uracil phosphoribosyltransferase locus from Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:5749–5753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan WJ Jr, Chiang CW, Wilson CM, Naguib FN, el Kouni MH, Donald RG, Roos DS. 1999. Insertional tagging of at least two loci associated with resistance to adenine arabinoside in Toxoplasma gondii, and cloning of the adenosine kinase locus. Mol Biochem Parasitol 103:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(99)00114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachrach U, Schnur LF, El-On J, Greenblatt CL, Pearlman E, Robert-Gero M, Lederer E. 1980. Inhibitory activity of sinefungin and SIBA (5′-deoxy-5′-S-isobutylthio-adenosine) on the growth of promastigotes and amastigotes of different species of Leishmania. FEBS Lett 121:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelouzat MA, Lawrence F, Robert-Gero M. 1993. Characterization of sinefungin-resistant Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Parasitol Res 79:683–689. doi: 10.1007/BF00932511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phelouzat MA, Basselin M, Lawrence F, Robert-Gero M. 1995. Sinefungin shares AdoMet-uptake system to enter Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Biochem J 305(Part 1):133–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dridi L, Ahmed Ouameur A, Ouellette M. 2010. High affinity S-adenosylmethionine plasma membrane transporter of Leishmania is a member of the folate biopterin transporter (FBT) family. J Biol Chem 285:19767–19775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dube DK, Mpimbaza G, Allison AC, Lederer E, Rovis L. 1983. Antitrypanosomal activity of sinefungin. Am J Trop Med Hyg 32:31–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg B, Rattendi D, Lloyd D, Sufrin JR, Bacchi CJ. 1998. Effects of intermediates of methionine metabolism and nucleoside analogs on S-adenosylmethionine transport by Trypanosoma brucei brucei and a drug-resistant Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. Biochem Pharmacol 56:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inselburg J. 1984. Induction and selection of drug resistant mutants of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 10:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(84)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C, Xiao B, Jiang Y, Zhao Y, Li Z, Gao H, Ling Y, Wei J, Li S, Lu M, Su XZ, Cui H, Yuan J. 2014. Efficient editing of malaria parasite genome using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. mBio 5:e01414–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01414-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner JC, Platt RJ, Goldfless SJ, Zhang F, Niles JC. 2014. Efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Methods 11:915–918. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghorbal M, Gorman M, Macpherson CR, Martins RM, Scherf A, Lopez-Rubio JJ. 2014. Genome editing in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Biotechnol 32:819–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan A, Shaik JS, Behnke M, Wang Q, Dubey JP, Lorenzi HA, Ajioka JW, Rosenthal BM, Sibley LD. 2014. NextGen sequencing reveals short double crossovers contribute disproportionately to genetic diversity in Toxoplasma gondii. BMC Genomics 15:1168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.